Abstract

Background:

It is a challenge to treat acne scars and a multimodal combination approach is necessary. While fractional CO2 lasers (FCLs) are an established treatment option, the role of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in the treatment of acne scars is not established though it is being used extensively in other fields of medicine owing to its healing properties. We combined the two methods to assess the proposed synergistic action on acne scars.

Aims and Objectives:

To evaluate the effect of FCL alone vs FCL combined with PRP on the quality of acne scars.

Materials and Methods:

This is a left–right split-face comparison study with 30 patients with moderate-to-severe acne scars. The patients underwent three sessions of FCL and FCL + topical PRP on right and left sides of the face, respectively, at monthly intervals.

Results:

There was significant improvement on both sides of the face (right side, P = 0.001; left side, P = 0.0001), but the difference between the right and the left sides of the face was not statistically significant (P = 0.2891). The symptoms of redness, edema, and pain on the treated areas with laser were significantly lesser on the FCL + PRP (left) side as compared to the FCL-only (right) side.

Conclusion:

Both methods were effective in management of acne scars. Addition of PRP does not improve the scar quality; however, the downtime and inflammation associated with laser treatment gets significantly reduced on the PRP-treated side.

Keywords: Acne scar revision, fractional CO2, topical PRP

INTRODUCTION

Acne is a very common occurrence among adolescents, which may sometimes persist into adulthood. A very common complication of acne is scarring that affects about 14% individuals.[1] It may have a negative impact on the psychology, self-esteem, and also the quality of life of an individual. Acne scars may be atrophic or hypertrophic. Several modalities of treatment are available for acne scar resurfacing such as chemical peels, chemical reconstruction of skin scars using trichloroacetic acid (TCA CROSS), dermabrasion, microdermabrasion, punch floatation, punch and dermal grafting, scar excision and suture, ablative and nonablative lasers, and combined therapies for atrophic scars whereas intralesional steroid injection, cryotherapy, silicone gels, and other surgical procedures for hypertrophic and keloidal scars.[2]

Fractional CO2 laser (FCL) as monotherapy has been an established treatment option for scar correction.[3,4,5,6,7,8] This therapy is based on the principle of fractional photothermolysis. It creates microscopic thermal wounds to achieve homogeneous thermal damage at a particular depth within the skin.

The clinical applications of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) have been used and studied since the 1970s. It has been used clinically in humans for its healing properties attributed to the increased concentrations of autologous growth factors and secretory proteins that may enhance the healing process on a cellular level. In dermatology, PRPs have been used for skin rejuvenation, ulcer management, and alopecia.[9,10] Monotherapy with intradermal PRP for acne scars has been reported to be beneficial.[11] Recently, topical and intradermal PRP injections have been used for acne scar revision combined with laser therapy with mixed results.[12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]

As FCL creates wounds on the skin and PRP is known to aid in wound healing, combining the two would probably result in synergistic action.[21] A split-face study in Korean patients reported that the combination of FCL and PRP enhances recovery of laser-damaged skin and synergistically improves the clinical appearance of acne scars.[15]

Lack of studies in an Indian setting prompted us to undertake this study. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of FCL alone vs FCL + topical PRP on the quality of acne scars.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a left–right split-face prospective comparison study carried out in patients who presented with atrophic acne scars to the Dermatology OPD of a tertiary care center of Eastern India between August 2015 and January 2017.

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee and a written informed consent was obtained from each patient before recruitment.

Patients underwent three sittings of FCL and FCL + topical PRP on right and left sides of the face, respectively, at monthly intervals. The final evaluation was done 1 month after the third session.

A full-face FCL + PRP was performed in all the patients at the fourth visit to overcome the possible ethical issues though that was not part of the proposed study.

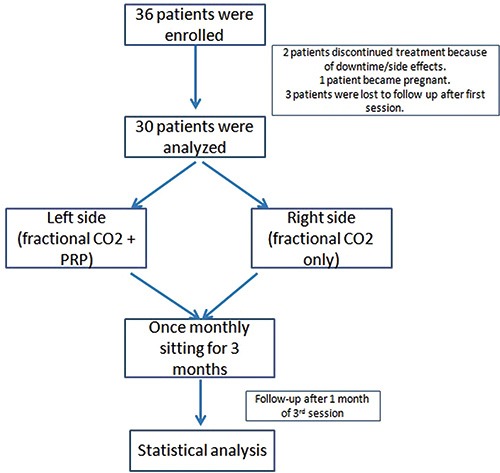

The flowchart of patients in the study is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients

Inclusion criteria

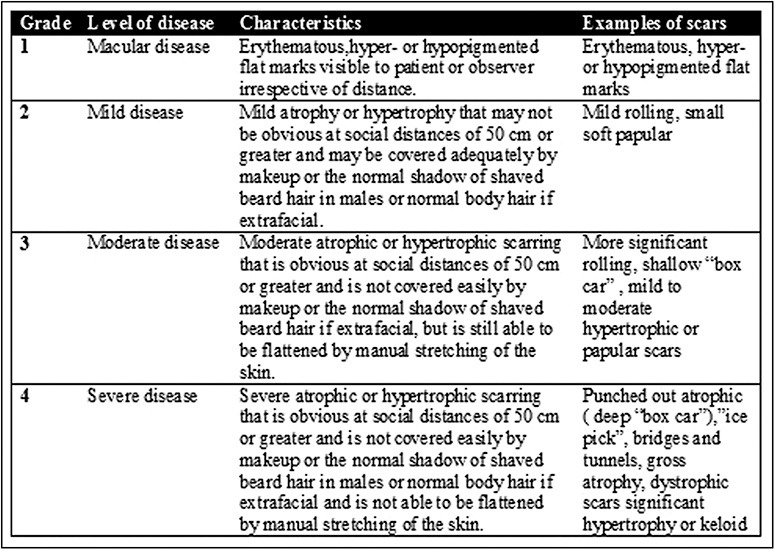

All patients aged between 18 and 40 years (skin types III, IV, V) with moderate-to-severe acne scars (as per Goodman and Baron’s acne scar grading scale) were included in this study [Figure 2].[22]

Figure 2.

Goodman and Baron’s qualitative scar scale

Exclusion criteria

The patients with a predisposition to keloid, active inflammation, herpes, HIV, HBV infection, oral isotretinoin use in preceding 6 months, diabetes mellitus, collagen vascular disease, ablative or nonablative laser skin resurfacing within the preceding 12 months, pregnant or lactating, bleeding diathesis, and unreasonably high expectations were excluded from this study.

Scoring

High-resolution photographs of both sides of the face were taken before the first treatment session and 4 weeks after the third session. The third observer, who was unaware of our protocol, scored the scars using Goodman and Baron’s quantitative global acne scar grading system at baseline and at the end of the study.

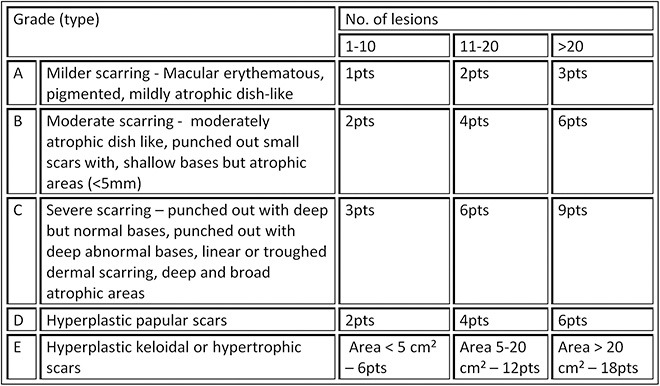

The quantitative scoring system involves lesion counting and a tallying up of number and severity according to an organized grading system as shown in Figure 3 (min 0 to max 84).[23]

Figure 3.

Goodman and Baron’s quantitative scar scale

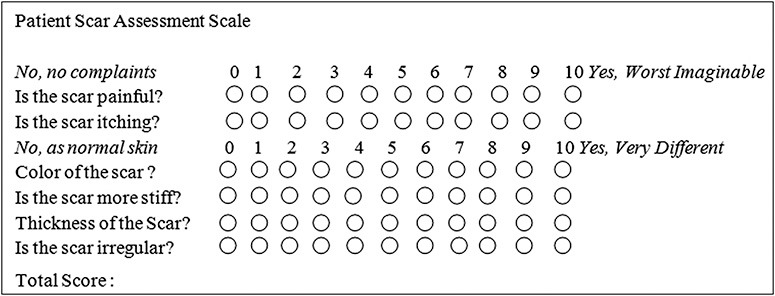

Visual Scar Assessment Questionnaire was also filled up by the observer [Figure 4] and by the patient [Figure 5] at baseline and the end of the study.

Figure 4.

Observer visual scar assessment scale

Figure 5.

Patient visual scar assessment scale

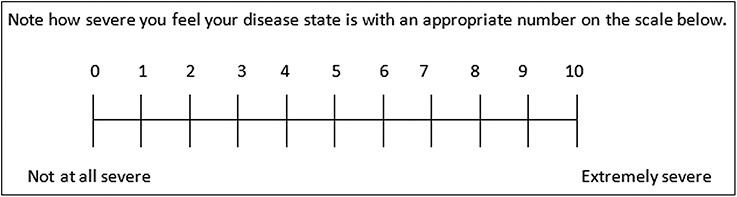

Patients were followed up after 72 h after each session to assess procedure-related adverse events (i.e., erythema, edema, and pain) and were asked to rate the redness, pain, and swelling on each side of the face on a visual analog scale of 0–10, a score of 10 being the most severe for each of the three parameters for each side of the face.

An overall patient satisfaction score on a scale of 0–10 was also obtained before and after the treatment [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Visual disease severity scale

Fractional CO2 device

A 30-W FIRE-XEL ablative FCL device from Bison Medical approved by the Korean FDA was used.

The topical anesthetic cream was applied for 30–45 min before the procedure. The energy delivered was 200 mJ in the first session with 10% increase in every subsequent session.

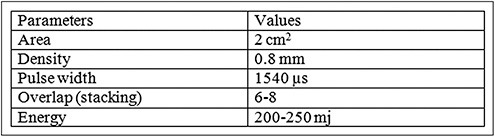

FCL settings are given in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Laser settings used

PRP preparation

A two-stage centrifuging process was performed[13] using an R8C centrifuge device (REMI Sales & Engineering Ltd. Goregaon (East), Mumbai – 400063. Maharashtra, India) to obtain PRP. Whole blood samples (10 mL) were drawn from patient’s medial cubital vein under aseptic conditions and transferred to a vial containing an anticoagulant. It was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min. Platelet-poor plasma, PRP, and a few RBCs were aspirated into a new tube and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min. The middle layer that consists of the PRP was aspirated for topical application immediately after the FCL treatment. The patient remained in the supine position until the site of PRP application dried up.

Postsession advise

Patients were advised to use a physical sunscreen during the daytime, a bland emollient during nighttime, and mild cleansers for facewash. They were counseled for the development of transient erythema, edema, hyperpigmentation, and dryness.

Statistical analysis

Paired t-test was used to compare Goodman and Baron’s qualitative scar grading before and after the treatment, patient and observer scar assessment, and overall disease self-assessment by the patient before and after the treatment. Unpaired t-test was used to compare Goodman and Baron’s quantitative scar grading for right side vs left side of the face at baseline and final score, men vs women, age, and duration of disease. The symptoms on right and left sides of the face at 72 h after each session were also compared using unpaired t-test.

A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

All the calculations were done using the Microsoft Excel (version Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2010 for Windows).

RESULTS

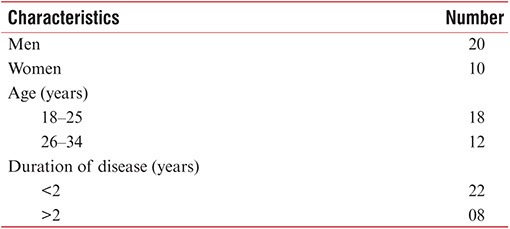

Thirty-six patients were found to be eligible and were enrolled in this study. A total of 30 patients, who completed the study, were then selected for analysis. There were 20 men and 10 women in the final analysis. The mean age of the participants was 25.06 ± 4.44 years. The mean duration of the presence of scars was 2.13 ± 1.00 years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

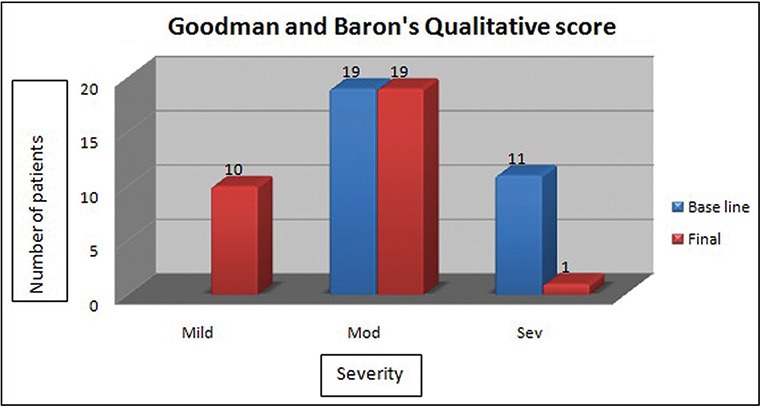

There were 19 patients with moderate scars and 11 with severe scars at baseline as assessed using Goodman and Baron’s qualitative scar scale. At the final scoring, there were 10 patients with mild scars, 19 with moderate scars, and 1 with severe scars [Figure 8]. The mean baseline score was 3.36 ± 0.49 and mean final score was 2.7 ± 0.53, and the difference between the baseline and final scores was statistically significant (P = 0.0001).

Figure 8.

Goodman and Baron’s qualitative scores

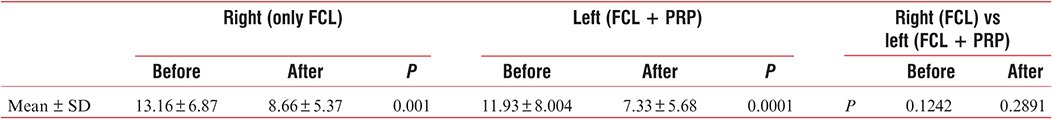

The mean baseline Goodman and Baron’s quantitative score on the right side was 13.16 ± 6.87 and mean final score at the end of the study was 8.66 ± 5.37. On the left side, the mean baseline score was 11.93 ± 8.004 and mean final score was 7.33 ± 5.68. There was statistically significant difference in the quality of scars when the baseline scores were compared with the final scores of each side individually. Before and after scores were statistically significant (P = 0.0001) on the right side and similar results were seen on the left side (P = 0.0001) indicating excellent improvement in the quality of scars. The baseline scores for the right and left sides of the face indicated that severity of scars was similar on both sides of the face (P = 0.1242) and that they were comparable at the start of treatment. The final scores indicated no significant difference in the quality of scars between the right and the left sides of the face (P = 0.2891). Though there was a significant improvement on both sides of the face, the addition of PRP to FCL on the left side of the face did not result in superior scar improvement as compared to the right side of the face that was treated with FCL only [Table 2, Figures 9–11].

Table 2.

Goodman and Baron's quantitative scores

Figure 9.

Before and after clinical photographs of patient 1

Figure 11.

Before and after clinical photographs of patient 3

Figure 10.

Before and after clinical photographs of patient 2

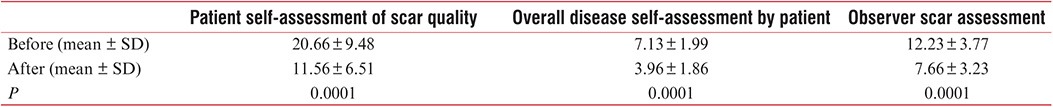

The mean baseline score of patient self-assessment of scars was 20.66 ± 3.77 and the final score was 11.56 ± 6.51; the difference between before and after scores was statistically significant (P = 0.0001). The patients were also asked to score themselves on an overall basis regarding their scars on a scale of 0–10 before and after the treatment. The mean baseline score was 7.13 ± 1.99 and mean final score was 3.96 ± 1.86, and the difference was found to be statistically significant [Table 3].

Table 3.

Visual scar assessment scores (before vs after)

The observer visually scored the patients under three parameters with a maximum of 10 points each and a maximum total score of 30 points. The mean baseline score was 12.23 ± 3.77 and mean final score was 7.66 ± 3.23, and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.0001) [Table 3].

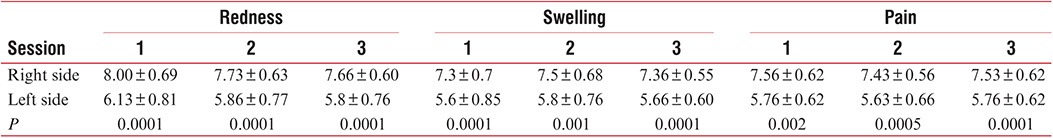

Each patient was followed up 3 days after each session to assess the subjective symptoms experienced (i.e., redness, swelling, and pain) in the treated areas. The redness, swelling, and pain experienced by each patient were significantly lesser on the side treated with FCL + PRP (left side) than that on the FCL-only treated side (P < 0.05) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Symptoms at 72 h after treatment session

DISCUSSION

Acne scars are a challenging dermatological condition and often require a multimodal approach to achieve desirable results. With the existing treatment options, newer modalities such as FCL and PRP are practiced by the dermatologists to deliver effective treatment with minimum adverse effects.

Our study had 30 patients in the age range of 18–34 years. There was no difference in the scar outcome, irrespective of the procedure followed, across the age range in our study population (right side, P = 0.8928; left side, P = 0.8460). Minimas[24] reported that in an otherwise healthy individual in any age group there is no difference in healing capacity. No significant difference in scar outcome across the age range would probably be because patients belong to the adult age group and there were no patients of extreme age gap. In our study, follow-up was done 1 month after the last session, which was too less to draw a conclusion on scar outcome.

In our study, the majority of the patients were men; however, there was no significant difference in the final scar quality between men and women (right side, P = 0.9077; left side, P = 0.9108). This is in contrast to the study by Dao and Kazin[25] who reported that estrogen can help in better wound healing. However, they also concluded that the patient’s gender does not always require radical alteration of treatment approach and also there is a lack of randomized controlled trials regarding gender differences in wound healing.[25]

The mean duration of the presence of scars in our patients was 2.13 ± 1.00 years (range 1–5 years). We divided the patients into two groups. One group with the presence of scars for more than 2 years and the other group with scars for less than 2 years. We did not find any significant difference in the quality of scars between the two groups (right side, P = 0.7342; left side, P = 0.9274).

One patient remained in the severe grade after the treatment when scored on Goodman and Baron’s qualitative scar scale. Although he showed improvement with the smaller and more superficial scars and even in his own subjective assessment, he still qualified for the severe grade of scars from the clinician’s assessment. The other patients, however, moved to a lower grade of scarring after treatment (i.e., from severe to moderate or moderate to mild). None of the patients showed complete clearance at the end of the study period. Further continuation of treatment might help to achieve a better outcome as scars only modify but never disappear completely.

Lee et al.[15] conducted a study on 14 patients with acne scars and treated them with two sessions of FCL on both sides of the face, and one side of the face was given intradermal PRP and the other side intradermal saline that was randomly selected. The clinical improvement was reported to be better on the PRP-treated site on a quartile grading scale. Shah et al.[20] carried out a split-face study on 30 patients with FCL on both sides and intradermal saline on one side and intradermal PRP on the other side on the fifth day after the laser session. They reported significant improvement on both sides of the face, but blinded observer and patient noted better improvement on the PRP-treated site. Zhu et al.[13] used erbium fractional laser with topical PRP in 22 patients with acne scar and reported excellent clinical improvement and patient satisfaction on the PRP-treated patients. In our study, all patients showed statistically significant improvement in the quantitative scoring of scars on both FCL-only treated side (before vs after, P = 0.001) and FCL + PRP treated side (before vs after, P = 0.0001). But the difference between right side (FCL-only) and left side (FCL + PRP) was not statistically significant at the end of our study(P = 0.2891), which is in contrast to the aforementioned studies. Addition of PRP did not result in a superior scar modification at the end of 4 months, which was similar to the findings of Faghihi et al.[19] They injected PRP intradermally on randomly selected sides of the face immediately after FCL and normal saline on the other side. The possible explanation would be the time taken by the scars after the procedure to modify is long and is probably partially modified at 4 months. The questionnaire-based observer assessment of scars (vascularity, pigmentation, and thickness) showed a statistically significant improvement in the before and after scores (P = 0.0001). This indicates there is definite change in the visual quality of scars after the treatment.

The overall visual analog score of disease severity and questionnaire-based self-assessment of scars (pain, itching, color, stiffness, thickness, and irregularity) also showed statistically significant improvement in the before and after scores. These findings were similar to the findings of several studies.[13,14,18,19,20,26] This indicates that patients were satisfied with the treatment outcome. However, the addition of PRP on the left half of the face did not affect the final outcome of the scar.

The patients were also followed up on the third day after the procedure for subjective assessment of three symptoms, i.e., redness, swelling, and pain in the treated areas [Table 4]. Each of the three symptoms was milder in severity on the side treated with FCL + PRP and the difference was statistically significant. This is in accordance with several studies where PRP was used after laser treatment.[14,27] Faghihi et al.[19] reported that though there was better scar correction on the FCL + intradermal PRP side, it was not statistically significant and that there were more local side effects on the PRP-treated side. In our study, we smeared the PRP topically instead of injecting it, hence avoiding the trauma of repeated injections on an already laser-damaged area.

In conclusion, both FCL and FCL + topical PRP improve the quality of acne scars significantly. Addition of topical PRP did not alter the final scar outcome significantly when compared with FCL. However, the FCL-associated adverse events (i.e. redness, swelling, and pain) improved faster and significantly better on the PRP-treated side. Topically smeared PRP in combination with FCL could be recommended as it significantly improves the downtime of the FCL.

Limitations

Long-term follow-up was not done as scars usually modulate over a long period.

There were a limited number of sessions as it was a time-bound study.

Larger sample size and longer follow-up are needed that would probably put more light on the outcome of acne scars.

Previous presentation: part of the work was presented for award paper in Mid-Dermacon 2016 held at Bhubaneswar on August 13, 2016.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sardana K, Manjhi M, Garg VK, Sagar V. Which type of atrophic acne scar (ice-pick, boxcar, or rolling) responds to nonablative fractional laser therapy.? Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:288–300. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salim T, Ghiya R. Surgical management of acne scars. In: Mysore V, editor. ACS(I) textbook on cutaneous and aesthetic surgery. 1st ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2013. pp. 392–406. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campolmi P, Bonan P, Cannarozzo G, Bassi A, Bruscino N, Arunachalam M, et al. Highlights of thirty-year experience of CO2 laser use at the Florence (Italy) Department of Dermatology. Scientific World J 2012. 2012:546528. doi: 10.1100/2012/546528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Taweel AAI, El-Rahman SHA. Assessment of fractional CO2 laser in stable scars. Egypt J Dermatol Venerol. 2014;34:74–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majid I, Imran S. Fractional CO2 laser resurfacing as monotherapy in the treatment of atrophic facial acne scars. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:87–92. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.138326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedelund L, Haak CS, Togsverd-Bo K, Bogh MK, Bjerring P, H';dersdal M. Fractional CO2 laser resurfacing for atrophic acne scars: a randomized controlled trial with blinded response evaluation. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:447–52. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walgrave SE, Ortiz AE, MacFalls HT, Elkeeb L, Truitt AK, Tournas JA, et al. Evaluation of a novel fractional resurfacing device for treatment of acne scarring. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41:122–7. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho SB, Lee SJ, Kang JM, Kim YK, Chung WS, Oh SH. The efficacy and safety of 10,600-nm carbon dioxide fractional laser for acne scars in Asian patients. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1955–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehryan P, Zartab H, Estarabadi AR, Firooz A. Assessment of efficacy of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on infraorbital dark circles and crow';s feet wrinkles. J Cosm Dermatol. 2014;13:72–8. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarano A, Iezzi G, Di Cristinzi A, Bertuzzi GL, Carinci F, Lauritano D. Full-facial rejuvenation with autologous platelet-derived growth factors. Eur J Inflamm. 2012;10:31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nofal E, Helmy A, Nofal A, Alakad R, Nasr M. Platelet-rich plasma versus CROSS technique with 100% trichloroacetic acid versus combined skin needling and platelet rich plasma in the treatment of atrophic acne scars: a comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:864–73. doi: 10.1111/dsu.0000000000000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster TE, Puskas BL, Mandelbaum BR, Gerhardt MB, Rodeo SA. Platelet-rich plasma: from basic science to clinical applications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:2259–72. doi: 10.1177/0363546509349921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu JT, Xuan M, Zhang YN, Liu HW, Cai JH, Wu YH, et al. The efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma combined with erbium fractional laser therapy for facial acne scars or acne. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:233–7. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gawdat HI, Hegazy RA, Fawzy MM, Fathy M. Autologous platelet rich plasma: topical versus intradermal after fractional ablative carbon dioxide laser treatment of atrophic acne scars. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:152–61. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JW, Kim BJ, Kim MN, Mun SK. The efficacy of autologous platelet rich plasma combined with ablative carbon dioxide fractional resurfacing for acne scars: a simultaneous split-face trial. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:931–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.01999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loesch MM, Somani A-K, Kingsley MM, Travers JB, Spandau DF. Skin resurfacing procedures: new and emerging options. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:231–41. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S50367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O';Daniel TG. Multimodal management of atrophic acne scarring in the aging face. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35:1143–50. doi: 10.1007/s00266-011-9715-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin MK, Lee JH, Lee SJ, Kim NI. Platelet-rich plasma combined with fractional laser therapy for skin rejuvenation. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:623–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faghihi G, Keyvan S, Asilian A, Nouraei S, Behfar S, Nilforoushzadeh MA. Efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma combined with fractional ablative carbon dioxide resurfacing laser in treatment of facial atrophic acne scars: a split-face randomized clinical trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:162–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.174378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah S, Mehta B, Borkar M, Aswani R. Study of safety and efficacy of autologous platelet rich plasma combined with fractional CO2 laser in the treatment of post acne scars: a comparative simultaneous split-face study. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5:1344–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Na JI, Choi JW, Choi HR, Jeong JB, Park KC, Youn SW, et al. Rapid healing and reduced erythema after ablative fractional carbon dioxide laser resurfacing combined with the application of autologous platelet-rich plasma. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:463–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring—;a quantitative global scarring grading system. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5:48–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2006.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minimas DA. Ageing and its influence on wound healing. Wounds UK. 2007;3:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dao H, Jr, Kazin RA. Gender differences in skin: a review of the literature. Gend Med. 2007;4:308–28. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu PX, Diao WQ, Qi ZL, Cai JL. Effect of dermabrasion and ReCell ®; on large superficial facial scars caused by burn, trauma and acnes. Chin Med Sci J. 2016;31:173–9. doi: 10.1016/s1001-9294(16)30047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim H, Gallo J. Evaluation of the effect of platelet-rich plasma on recovery after ablative fractional photothermolysis. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;17:97–102. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2014.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]