Abstract

Introduction:

Androgenetic alopecia is a common form of alopecia with multifactorial etiology. Finasteride and minoxidil are approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Balding scalp is believed to have relative microvascular insufficiency. Blood vessels in the scalp travel through the intramuscular plane. Intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin relaxes muscles and thereby increases blood flow in balding scalp. We conducted a pilot study to evaluate the efficacy of botulinum toxin in androgenetic alopecia management.

Material and Methods:

The study was conducted in a tertiary care center. A total of 10 male patients with androgenetic alopecia meeting inclusion criteria of the study were included. In the scalp, 30 sites were injected with 5 U of botulinum toxin in each site. Preprocedure photograph taken and evaluation was done, which was repeated after 24 weeks. Efficacy was assessed by photography and self-assessment scoring was done by patients.

Results:

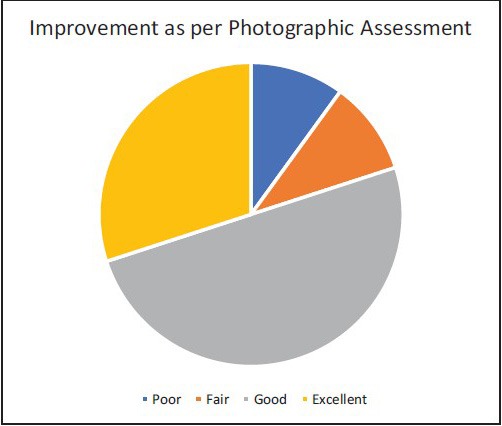

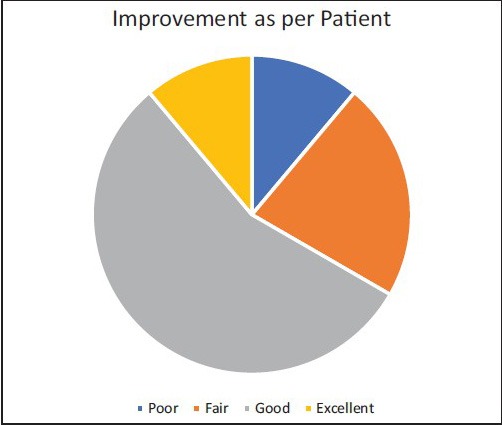

Of 10 patients, 8 had good to excellent response on photographic assessment. At the end of 24 weeks, 1 patient showed poor and 1 showed fair response to treatment. As per self-assessment, 7of 10 patients showed good to excellent response. Two patients had fair response and 1 patient showed poor response to treatment.

Conclusion:

Botulinum toxin was found to be safe and effective therapy for the management of androgenetic alopecia in this pilot study. Studies with larger sample size and randomized controlled trials are required to establish the role of botulinum toxin in the management of androgenetic alopecia.

Keywords: Androgenetic alopecia, botulinum toxin, male pattern baldness

INTRODUCTION

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is the most common form of baldness and affects almost 80% men in a lifetime.[1,2] It has multifactorial etiology resulting from the interaction of genetic and environmental factors. It is characterized by progressive miniaturization of hair follicles. The terminal hairs get converted to intermediate and then vellus hairs; however, the number of hair follicles per unit area remains same.[3] Hair follicle contains enzyme 5α-reductase that converts testosterone to more potent dihydrotestosterone (DHT). This DHT is responsible for miniaturization of hair follicle. Oral finasteride and topical minoxidil are the only FDA-approved treatment for AGA management. Finasteride is a 5α-reductase inhibitor, which prevents the conversion of testosterone to DHT. Oral minoxidil is an antihypertensive and a vasodilator. Topical minoxidil has a complex mechanism of action. It results in the synthesis of prostaglandins and vascular endothelial growth factors in dermal papilla and the opening of potassium channels, resulting in an increase in anagen to telogen ratio.[4] Botulinum toxin has been tried for AGA management once previously.[5] We conducted a pilot study to find out the efficacy of botulinum toxin in AGA management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our study was conducted in Dermatology OPD of the tertiary care center. A total of 10 male patients aged 22–42 years with AGA reporting consecutively meeting inclusion criteria were included in the study. Institutional ethics committee clearance to conduct the study was obtained. Diagnosis of AGA was based on clinical examination and trichoscopy. Inclusion criteria for the study included male patients, Norwood–Hamilton grade II–IV, no treatment taken for last 6 months, consent to be part of study, and ready for regular follow-ups and photographs. Exclusion criteria were any concomitant diagnosis such as alopecia areata, localized infection precluding injection, and any concomitant medicines or comorbidities such as neuromuscular disorders, which preclude use of botulinum toxin or any needle phobia.

Injection

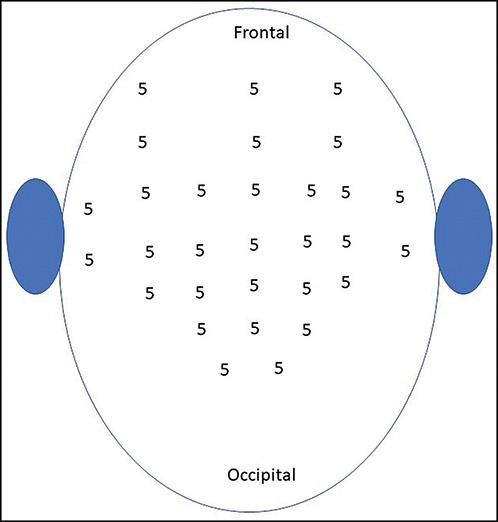

Botulinum toxin A 100 U was diluted in 1 mL normal saline. Insulin syringe of capacity 40 U/mL was used for injection, resulting in a concentration of 2.5 U every mark of insulin syringe. In 30 different sites, 5 U was injected resulting in a total of 150 U. Injections were intramuscular and sites were selected in frontalis, occipitalis, temporalis, and periauricular muscles [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Sites for injections

Efficacy assessment

Patients were assessed clinically and pretreatment photographs were taken. They were assessed at 24 weeks and repeat photographs were taken. They were also asked about the improvement in hair growth and it was graded objectively on a scale as 0, 1, 2, and 3 for poor, fair, good, and excellent. Photographs were also assessed by two observers and hair growth was graded as 0, 1, 2, or 3 for poor, fair, good, or excellent.

RESULTS

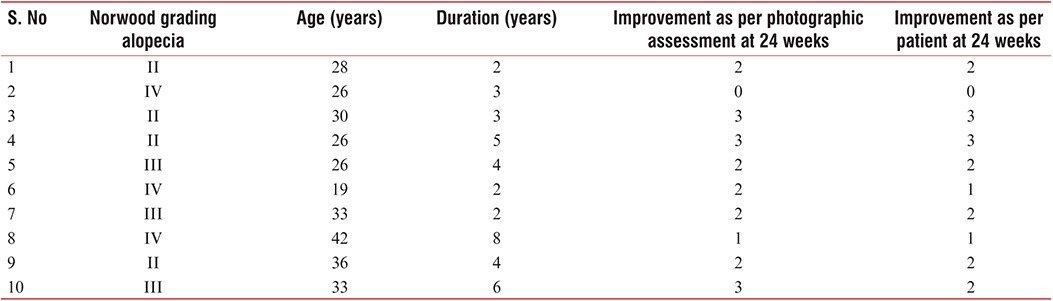

Result was assessed at the end of 24 weeks. Of 10 patients, 8 had good to excellent response on photographic assessment. One patient had poor and one showed fair response to treatment at the end of 24 weeks. As per self-assessment, 7 of 10 patients had good to excellent response. Two patients had fair response and one showed poor response [Table 1, Charts 1 and 2] [Figure 2–6]. No adverse effects were noted during the therapy.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and improvement at 24 weeks

Chart 1.

Improvement as per photographic assessment at 24 weeks

Chart 2.

Improvement as per patient at 24 weeks

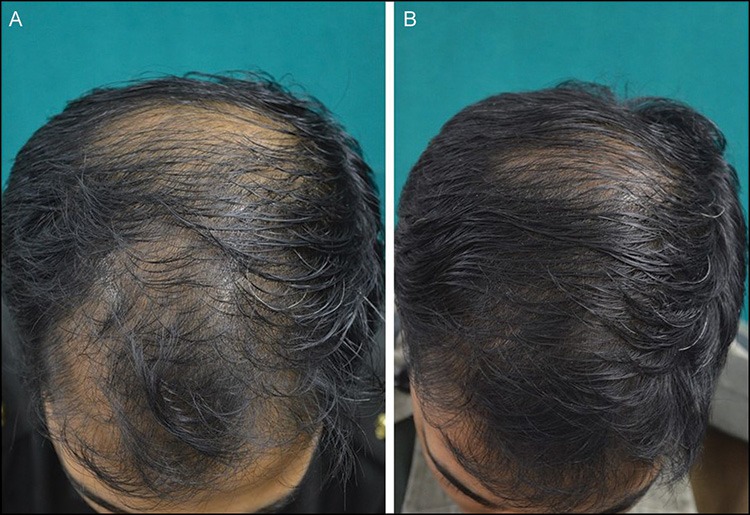

Figure 2.

(A and B) Excellent response seen at 24 weeks

Figure 6.

(A and B) Poor response seen at 24 weeks

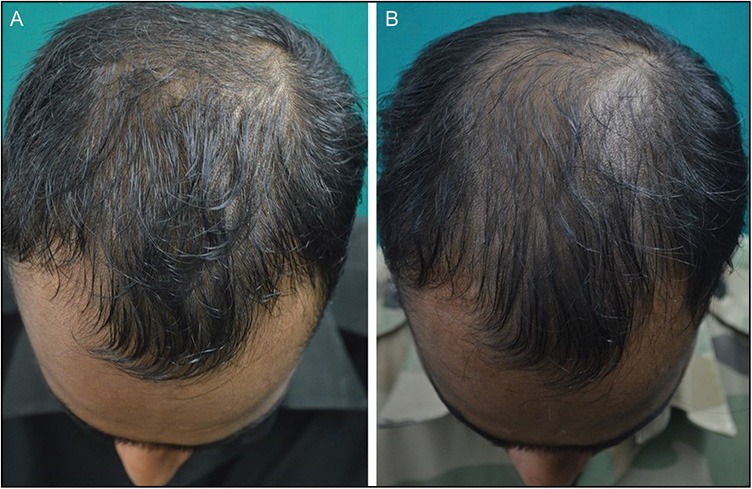

Figure 3.

(A and B) Excellent response seen at 24 weeks

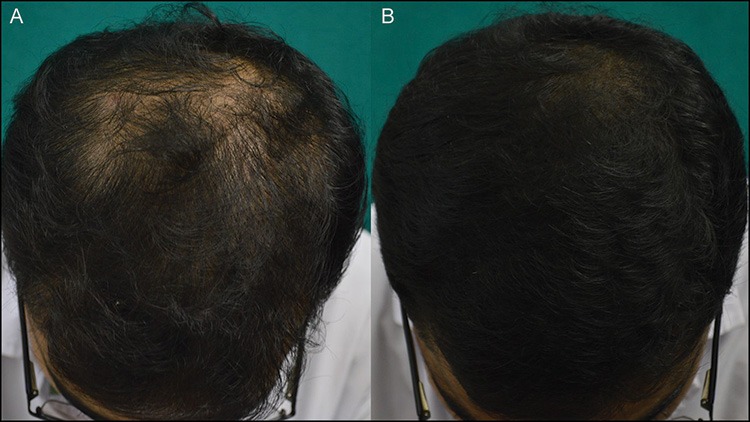

Figure 4.

(A and B) Good response seen at 24 weeks

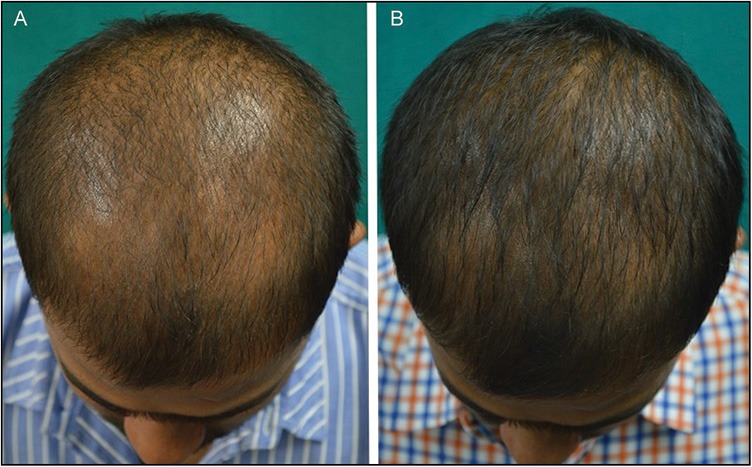

Figure 5.

(A and B) Fair response seen at 24 weeks

DISCUSSION

The exact pathogenesis of male pattern baldness is not yet known. There are various causative factors implicated in causation of male pattern baldness. Orentreich[6] proposed that minituarization of hair follicles occurs in genetically predisposed androgen-sensitive hair follicle. This androgenetic theory has been the most prevailing theory for male pattern baldness and antiandrogens such as finasteride are successfully used for the management of this condition.[6] Zappacosta[7] described treatment of male pattern baldness in patients receiving minoxidil for hypertension, and suggested topical minoxidil as an effective treatment. Few experimental studies suggested that subcutaneous blood flow in the scalp of a patient with male pattern baldness was greatly reduced as compared to controls. Goldman et al.[8] conducted an experiment in which they measured transcutaneous pO2 of the scalp in male pattern baldness and to find out whether bald scalp actually has some microvascular insufficiency. They found that resting transcutaneous pO2 was significantly lower in frontal bald scalp as compared to temporal hair-bearing scalp in patient with male pattern baldness. Transcutaneous pO2 in frontal bald scalp was also significantly lower as compared to hair-bearing frontal scalp of controls and transcutaneous pO2 of hair-bearing frontal and temporal scalp in controls were not significantly different.[8] This relative microvascular insufficiency possibly results because frontal and vertex areas are supplied by supratrochlear and supraorbital arteries, which are smaller branches of internal carotid artery, and it overlies galea aponeurotica, which is relatively less vascular as compared to the temporal and occipital areas, which overlie muscles.[9] The androgenetic theory states that minituarization of hair follicle results from the action of DHT. Hair follicles contain 5α-reductase enzyme that is responsible for peripheral conversion of testosterone to more active DHT. There is an increased accumulation of DHT in the affected follicle and disturbed DHT to estradiol ratio due to relative microvascular insufficiency, which leads to minituarization of hair follicle.[10]

Injection of botulinum toxin relaxes the muscle, which reduces pressure on the musculocutaneous and perforating vasculature, thereby potentially increasing the blood supply and transcutaneous pO2. This increased blood flow can also lead to washing out of accumulated DHT, thereby reducing the signal for minituarization of hair follicle. We found that botulinum toxin is an effective therapy for AGA management in our pilot study; however, larger studies and controlled trial to compare it with existing FDA-approved modalities need to be conducted. Transcutaneous pO2 and blood supply before and after botulinum injection, if conducted, will also provide some insight into the pathogenesis of this common disease and mechanism of action of botulinum toxin in AGA management.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tang PH, Chia HP, Cheong LL, Koh D. A community study of male androgenetic alopecia in Bishan, Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2000;41:202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sehgal VN, Kak R, Aggarwal A, Srivastava G, Rajput P. Male pattern androgenetic alopecia in an Indian context: a perspective study. J Europ Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:473–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lad V, Suryawanshi C, Sinhal A, Landge A, Wagh V, Jadhav N. Androgenic alopecia: current perspectives & treatments. 2017;6(3):641–53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rathnayake D, Sinclair R. Male androgenetic alopecia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1295–304. doi: 10.1517/14656561003752730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freund BJ, Schwartz M. Treatment of male pattern baldness with botulinum toxin: a pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:246e–8e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ef816d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orentreich N. Autografts in alopecias and other selected dermatological conditions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1959;83:463–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb40920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zappacosta AR. Reversal of baldness in patient receiving minoxidil for hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1480–1. doi: 10.1056/nejm198012183032516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldman BE, Fisher DM, Ringler SL. Transcutaneous PO2 of the scalp in male pattern baldness: a new piece to the puzzle. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:1109–16. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199605000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dingman RO, Argenta LC. The surgical repair of traumatic defects of the scalp. Clin Plast Surg. 1982;9:131–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sansone-Bazzano GA, Reisner RM, Bazzano G. Conversion of testosterone-1, 23H to androstenedione-3H in the isolated hair follicle of man. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1972;34:512–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem-34-3-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]