Abstract

A new method for the direct conversion of 4-pentenylsulfonamides to 2-formylpyrrolidines and a 2-ketopyrrolidine has been developed. This transformation occurs via aerobic copper-catalyzed alkene aminooxygenation where molecular oxygen serves as both oxidant and oxygen source. The 2-formylpyrrolidines can further undergo oxidative carbon–carbon bond cleavage in situ upon addition of DABCO, providing 2-pyrrolidinones. These transformations have been demonstrated for a range of 4-pentenylsulfonamides. 4-Pentenylalcohols also undergo oxidative cyclization to form γ-lactones predominantly. The reaction is chemoselective, oxidizing one alkene in the presence of others, and is compatible with several functional groups. Application of these reactions to the formal syntheses of baclofen and (+)-monomorine was demonstrated.

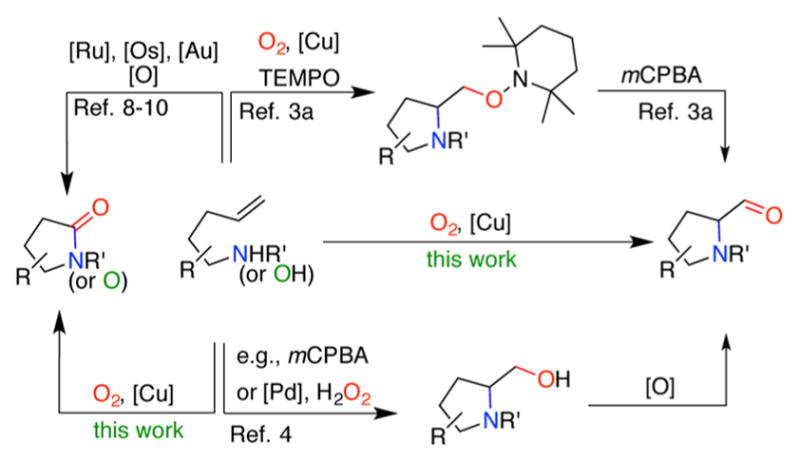

Aerobic copper facilitated organic reactions provide practical solutions for the syntheses of a broad range of organic molecules and have been the subject of intensive research.1 The range of copper oxidation states enables access to transformations that required both single and two-electron activation mechanisms. Molecular oxygen used in these reactions is often considered an ideal oxidant due to its low environmental impact and high atom economy. Significant natural abundance of copper and oxygen also make them better choices in comparison with more precious metal or organic oxidant combinations, especially when large-scale processes are involved. Unactivated alkenes are useful substrates that can be transformed via copper-catalyzed difunctionalization into a variety of N- and O-heterocycles.2 In one of these approaches, we developed an aerobic aminooxyganation reaction leading to (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO) adducts that can be subsequently converted to aldehydes (Scheme 1).3

Scheme 1.

Aminooxygenation of Alkenes/Oxidative C–C Bond Cleavage

Another strategy for the synthesis of N-heterocyclic aldehydes from alkenes includes aminohydroxylation/cyclization and subsequent oxidation of the resulting alcohol.4 Related studies report aerobic Au- and Fe-catalyzed synthesis of oxazole aldehydes,5 or aerobic Cu-catalyzed dehydrogenative amino-oxygenation affording nonenolizable N-heterocyclic aldehydes.6 Electrochemical-chemical oxidation has also been used, producing 2-phenyl pyrrolidinyl and piperidinyl ketones from the corresponding phenyl-substituted unsaturated sulfonamides in the presence of DMSO.7

Herein, we disclose a direct transformation of 4-pentenyl sulfonamides into 2-formylpyrrolidines via aerobic copper catalyzed aminooxygenation. A slight modification of the reaction conditions leads to the synthesis of the corresponding γ-lactams or γ-lactones that previously were available from identical starting materials but required use of more expensive ruthenium,8 osmium,9 or gold catalysts.10

Although Cu-catalyzed alkene aminooxygenation reactions dependent on stoichiometric terminal oxidants like PhI(OAc)2 or TEMPO have strong literature precedent,11 few aerobic Cu-catalyzed aminoxygenations that use molecular oxygen as both reactant and terminal oxidant have been reported,12 and none provide the aldehydes and lactams observed in this study (vide infra).

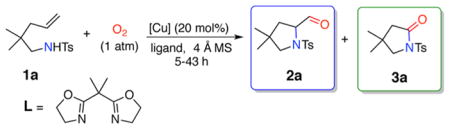

4-Pentenylsulfonamide 1a was thus subjected to various Cu(I) and Cu(II) catalysts, ligands, additives and bases in PhCH3 or PhCF3 under oxygen atmosphere (1 atm, balloon) at 105–120 °C as illustrated in Table 1 (see Supporting Information for full optimization screen).

Table 1.

Optimization of the Reaction Conditions

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Cu salt (20 mol%) | Ligand/base | Producta | ||

|

| |||||

| 1a | 2a | 3a | |||

| 1b | Cu(OTf)2 | Bis(oxazoline) (L) | 57 | 25 | 18 |

| 2b | CuI | L | 41 | 0 | 59 |

| 3b | CuBr | L | 45 | 16 | 39 |

| 4b | CuCN | L | 47 | 6 | 47 |

| 5c | CuCN | L | 6 | 6 | 88 (62) |

| 6b | CuCI | L | 0 | 20 | 80 |

| 7d | CuCI | L + DABCO | 9 | 0 | 91 (66) |

| 8b | CuCI | – | 0 | 77 | 23 |

| 9c | CuCI | – | 0 | 91 | 9 |

| 10e | CuCI | 1,10-phenanthroline | 65 | 10 | 25 |

| 11e | CuCI | 2,2′-bipyridine | 39 | 22 | 39 |

Relative ratio based on crude 1H NMR analysis (isolated percent yield).

Reaction run in PhCH3 at 105 °C for ca. 20 h.

Reaction run in PhCH3 at 120 °C for 41 h (entry 5) and 5 h (entry 9).

Reaction run in PhCF3 at 120 °C for 8 h, 15 mol % of CuCl, 17 mol % of L and 40 mol % of DABCO (added after 5 h) were used.

Reaction run in PhCF3 at 105 °C for 22 h. Ligands were complexed with [Cu] for 2 h at 60 °C prior to addition of reagents.

Under these conditions, varying amounts of aldehyde 2a and lactam 3a were formed. From this screen, we concluded that the copper source, ligand choice, and presence or absence of base have the most important impact on reactivity and selectivity. Only CuCl and CuCN enabled full conversion (Table 1, entries 5–9), but use of CuCN required longer reaction time (~40 vs ~20 h) and higher temperature (120 vs 105 °C) compared to CuCl. The higher reactivity of CuCl might be explained by it relatively lower activation energy in end-on O2 coordination via a di-μ-chloro complex.13 Application of CuCl as a catalyst for aerobic oxidative C–C bond cleavage in the synthesis of lactones from hemiketals has recently been demonstrated.14 Using CuCl alone allowed formation of aldehyde 2a as a major product (Table 1, entries 8 and 9). When CuCl or CuCN is combined with bis(oxazoline) ligand L, the major product is lactam 3a (Table 1, entries 5 and 6). Surprisingly, use of other bidentate ligands lowers both reactivity and selectivity (Table 1, entries 10 and 11). High selectivity toward lactam 3a can also be achieved by addition of a catalytic amount of 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO). This can be done after the first step of the reaction, when formation of aldehyde 2a is complete (disappearance of 1a monitored by TLC, Table 1, entry 7). In this case, for most substrates, use of ligand is not necessary (Table 2, conditions A). Use of DABCO likely accelerates deprotonation of the aldehyde, which was shown to be the rate-determining step in a related study on Cu-catalyzed C–C oxidative cleavage of aldehydes to ketones.15

Table 2.

Reaction Scope for Synthesis of 2-Pyrrolidinones

|

Conditions A: 1. CuCl (20 mol %), PhCH3, 105 °C, 4 Å MS (reaction times 5–16 h, see Supporting Information for each reaction); 2. +DABCO (40 mol %) for 3–10 h.

Conditions B: 1. CuCl (15 mol %), L (17 mol %), PhCF3, 120 °C, 4 Å MS for 5 h; 2. +DABCO (40 mol %) for 3 h.

Conditions C: CuCN (20 mol %), L (22 mol %), PhCH3, 120 °C, 4 Å MS for 41 h.

Conditions D: 1. CuCl (20 mol %), L (22 mol %), PhCF3, 105 °C, 4 Å MS for 17 h; 2. +DABCO (34 mol %) for 3 h. Ligands were complexed with [Cu] for 2 h.

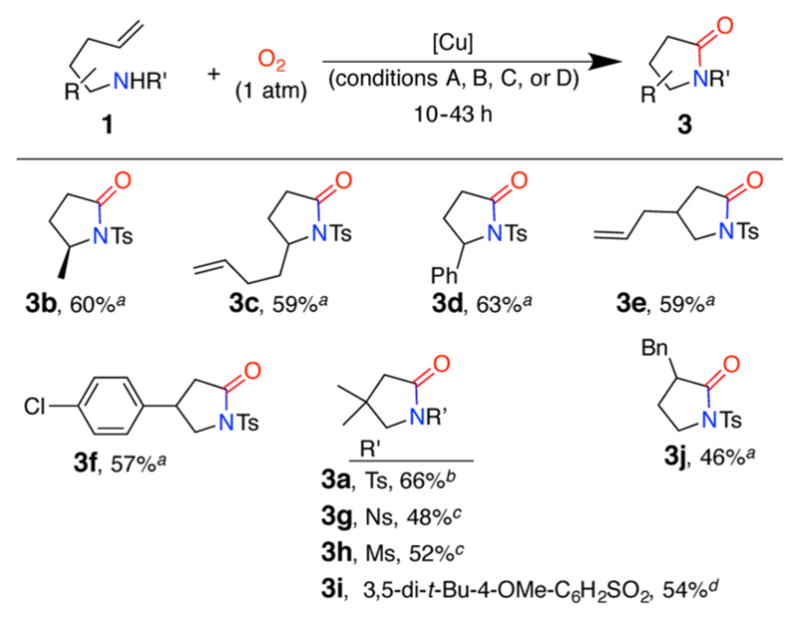

We employed the optimal lactam synthesis conditions (Table 1, entries 5, 7, and ligand free conditions A in Table 2) in the syntheses of several γ-lactams (Table 2).

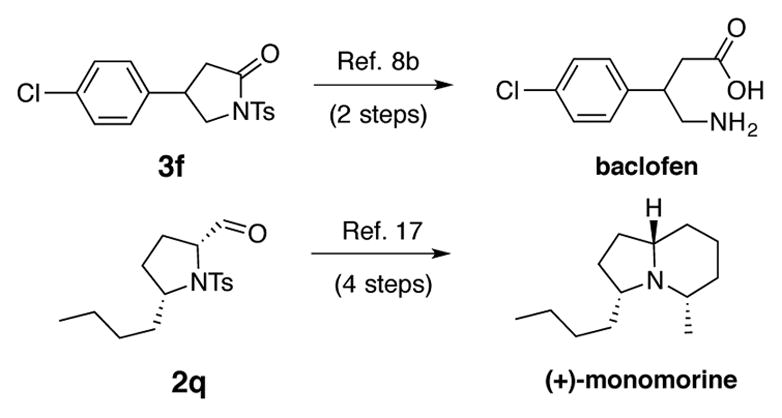

The reaction is compatible with both aliphatic and aromatic substituents at positions 1, 2 and 3 of the 4-pentenylsulfonamides and affords the products with moderate to good yields. The reaction works for 4-chlorophenylpentenyl sulfonamide 1f, which is an intermediate in the synthesis of baclofen, a skeletal muscle relaxant (Scheme 2).8b Additionally, the reaction is compatible with another alkene present in the molecule leading to chemoselective formation of lactams 3c and 3e. This chemoselectivity would be challenging to access via the alternative Ru-based approach. N-Tosyl-2-allylaniline did not provide much of the corresponding lactone under cyclization/oxidation conditions A, Table 2 (complex mixture obtained, not shown).

Scheme 2.

Formal Syntheses of Baclofen and (+)-Monomorine

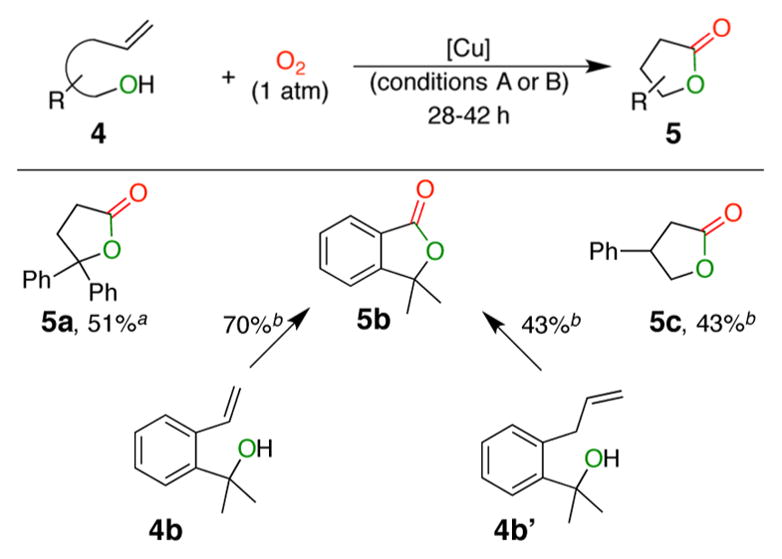

Using similar conditions, the method can be extended to the synthesis of γ-lactones from unsaturated alcohols (Table 3). When allylbenzene derivative 4b′ was used, the γ-lactone 5b was obtained, which suggests isomerization of the double bond under these conditions.

Table 3.

Reaction Scope for Synthesis of 2-Dihydrofuranones

|

Conditions A: CuCN (20 mol %), L (22 mol %), PhCH3, 120 °C, 4 Å MS.

Conditions B: CuCl (15 mol %), L (17 mol %), PhCF3, 120 °C, 4 Å MS. See Supporting Information for individual reaction times.

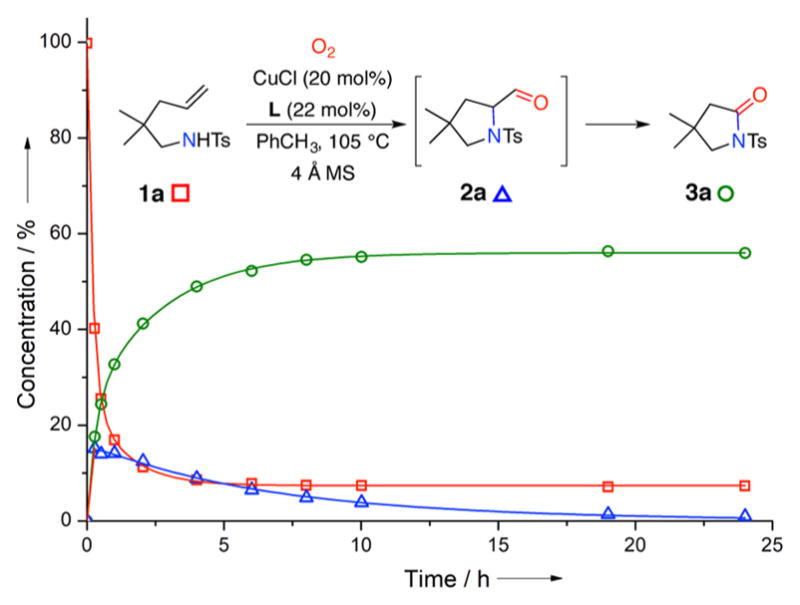

We next investigated the possibility that aldehyde 2a was an intermediates in the formation of lactam 3a. Submitting 2a to the reaction condition resulted in formation of 3a (see Scheme 4, vide infra, for a related experiment). This observation was consistent with a reaction kinetic profile that shows initial increase of aldehyde concentration that is later consumed in the lactam formation (Figure 1).

Scheme 4.

Mechanistic Investigation

Figure 1.

Kinetic profile of aminooxygenation/oxidative C–C bond cleavage.

Performing the reaction without ligand or base present is sufficient to prevent excessive lactam formation and to obtain the aldehyde in moderate to good yields (Table 1, entries 8 and 9). Ligand free conditions were tested for a variety of alkenes and proved their applicability to substrates containing another double bond (2c and 2e), chloride (2f), thioether (2n), ether (2o, 2p, and 2i), nitro group (2g) and furan (2r). The selectivity and stereochemistry of the major product depend on the substitution position of the 4-pentenylsulfonamide. A single diastereomer (cis) was observed in the crude 1H NMR spectra of 2,5-pyrrolidines (dr > 20:1) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Reaction Scope for Synthesis of 2-Formylpyrrolidines and 2-Ketopyrrolidine

Conditions A: CuCl (20 mol %), PhCH3, 105 °C, 4 Å MS.

Conditions B: CuCl (20 mol %), PhCH3, 120 °C, 4 Å MS.

Conditions C: CuCl (15 mol %), L (17 mol %), PhCF3, 120 °C, 4 Å MS. See Supporting Information for individual reaction times.

Poor diastereoselectivity (up to dr = 2:1) was found for 3,5-pyrrolidines 2s and 2f. Moderate diastereoselectivity (dr ~ 5:1) favoring trans products 2t and 2j was observed for 3,5-pyrrolidines. These stereochemical patterns are similar to those previously reported by us for Cu-catalyzed alkene aminoxygenation/cyclization using a TEMPO/O2 oxidative system.16 Use of the (R)-(+)-2,2′-isopropylidenebis(4-phenyl-2-oxazo-line) ligand gave 2a in a promising 25% yield and 44% ee (not shown, see Supporting Information for details). N-Tosyl-2-allylaniline provided aldehyde 2u in a modest 35% yield. Transformation of an internal alkene into ketone 2v was possible with addition of ligand L; however, full conversion was not achieved. In all of these reactions, the remainder of mass can be accounted for by some formation of lactam 3 (as in Table 2), some formation of the corresponding amino chloride, amino alcohol and carboamination product, and in some instances starting material (see Supporting Information for details).

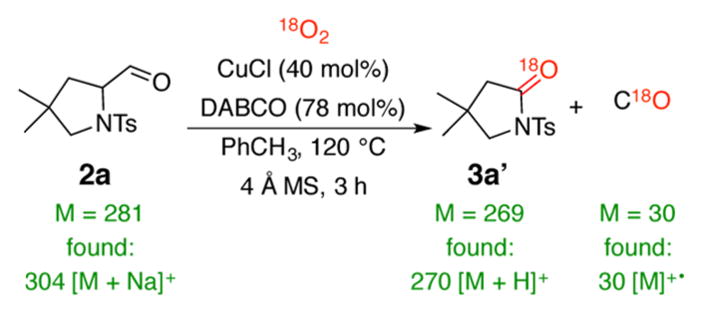

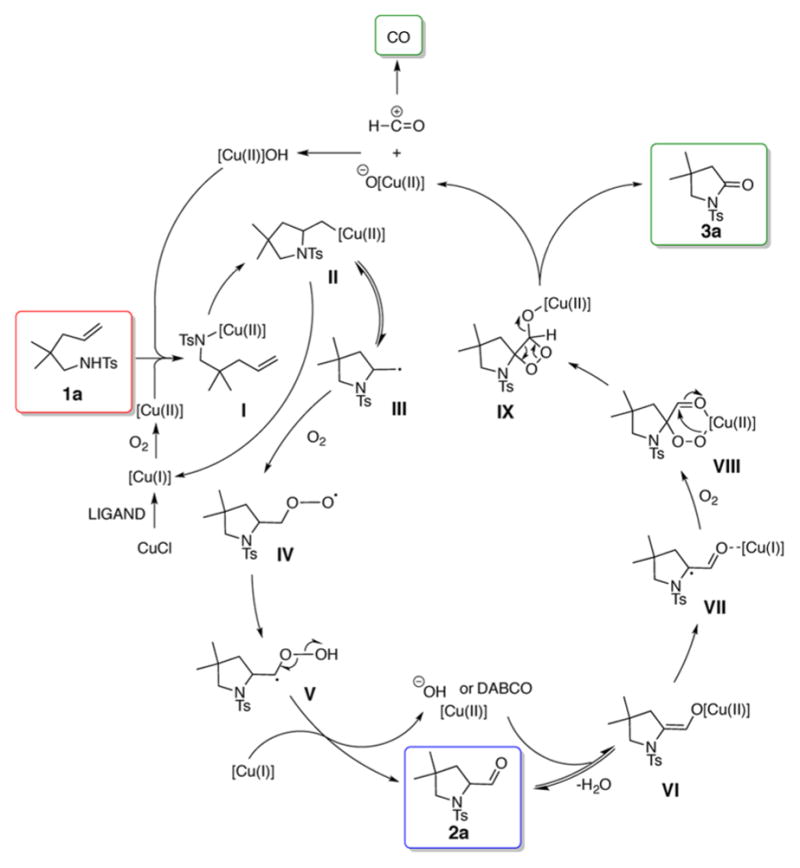

This aminooxygenation was performed on gram scale (3.4 mmol) providing aldehyde 2q in 61% yield. Aldehyde 2q is an intermediate in the synthesis of (+)-monomorine (Scheme 2).17 This modification reduced our previous formal synthesis of that trail pheromone by one step.16a We hypothesize that the reaction starts with oxidation of copper(I) to copper(II) by O2. Copper(II)-catalyzed alkene cis-aminocupration then affords an unstable organocopper(II) intermediate II that undergoes C–Cu homolysis to give primary radical III (Scheme 3).3 The radical reacts with molecular oxygen and leads to formation of aldehyde 2a.

Scheme 3.

Proposed Mechanism of Aminooxygenation/Oxidative C–C Bond Cleavage

Aldehyde 2a can either be isolated or, in the presence of in situ formed hydroxide or external base (DABCO) is transformed into copper(II) enolate VI. Reaction of the enolate with molecular oxygen gives peroxy intermediate VIII and then IX.18 Oxidative C–C bond cleavage then occurs to form lactam 3a and carbon monoxide. The CO was detected by mass spectrometry. In addition, we performed labeling studies with oxygen-18 to detect the source of oxygen in the final products (Scheme 4). In agreement with the proposed mechanism, we observed labeled lactam 3a′ and labeled carbon monoxide. These studies do not support formation of carbon monoxide from C–C bond cleavage of the 2-formylpyrrolidine carbonyl via an acyl radical15 but rather are consistent with a mechanism involving cyclic peroxo intermediates VIII and IX.18

In conclusion, we developed the first direct method of transforming 4-pentenylsulfonamides into 2-formylpyrrolidines, a reaction that can occur in high diastereoselectivity and provide useful heterocyclic intermediates. A slight change of cleavage to access the corresponding lactams and lactones. This work extends the scope of aerobic oxidative organic transformations and provides insight into further potential reaction developments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institute of General Medical Science for support of this work (GM 078383) and the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of States for a Fullbright fellowship to T.W. We thank Drs. Alice Bergmann and Valerie Frerichs (UB instrument center) for help with the mass spectrometry experiments.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b05680.

Experimental procedures and characterization of new compounds (PDF) NMR spectra (PDF)

References

- 1.(a) Allen SE, Walvoord RR, Padilla-Salinas R, Kozlowski MC. Chem Rev. 2013;113:6234. doi: 10.1021/cr300527g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McCann SD, Stahl SS. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:1756. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Greene JF, Hoover JM, Mannel DS, Root TW, Stahl SS. Org Process Res Dev. 2013;17:1247. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Chemler SR. J Organomet Chem. 2011;696:150. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bovino MT, Chemler SR. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:3923. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liwosz TW, Chemler SR. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2020. doi: 10.1021/ja211272v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Turnpenny BW, Chemler SR. Chem Sci. 2014;5:1786. doi: 10.1039/C4SC00237G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bovino MT, Liwosz TW, Kendel NE, Miller Y, Tyminska N, Zurek E, Chemler SR. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:6383. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Fuller PH, Kim JW, Chemler SR. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17638. doi: 10.1021/ja806585m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Paderes MC, Belding L, Fanovic B, Dudding T, Keister JB, Chemler SR. Chem - Eur J. 2012;18:1711. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Belding L, Chemler SR, Dudding T. J Org Chem. 2013;78:10288. doi: 10.1021/jo401665n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Select nonmetal catalyzed aminohydroxylation/cyclization: Thai K, Wang L, Dudding T, Bilodeau F, Gravel M. Org Lett. 2010;12:5708. doi: 10.1021/ol102536s.Moriyama K, Izumisawa Y, Togo H. J Org Chem. 2012;77:9846. doi: 10.1021/jo301523a.Liu GQ, Li L, Duan L, Li YM. RSC Adv. 2015;5:61137.. Select Pd-catalyzed aminooxygenation/cyclization: Zhu HT, Chen PH, Liu GS. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:1766. doi: 10.1021/ja412023b.Yin G, Mu X, Liu G. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:2413. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00328.. An Os-catalyzed aminohydroxylation/cyclization: Donohoe TJ, Churchill GH, Wheelhouse KMP, Glossop PA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:8025. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603240.

- 5.Peng HH, Akhmedov NG, Liang YF, Jiao N, Shi XD. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:8912. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang HG, Wang Y, Liang DD, Liu LY, Zhang JC, Zhu Q. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:5678. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Ashikari Y, Nokami T, Yoshida J. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:11840. doi: 10.1021/ja202880n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ashikari Y, Nokami T, Yoshida J. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:3322. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40315g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Carlsen PHJ, Katsuki T, Martin VS, Sharpless KB. J Org Chem. 1981;46:3936. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ibuka T, Schoenfelder A, Bildstein P, Mann A. Synth Commun. 1995;25:1777. [Google Scholar]; (c) Soto-Cairoli B, Soderquist JA. Org Lett. 2009;11:401. doi: 10.1021/ol802685e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Huang W, Ma JY, Yuan M, Xu LF, Wei BG. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:7829. [Google Scholar]; (e) Saikia B, Devi TJ, Barua NC. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:905. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26329g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Schomaker JM, Travis BR, Borhan B. Org Lett. 2003;5:3089. doi: 10.1021/ol035057f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Matsumoto K, Usuda K, Okabe H, Hashimoto M, Shimada Y. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2013;24:108. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitahara H, Sakurai H. Chem Lett. 2012;41:1328. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Chiba S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016;57:3678. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhu X, Chiba S. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:4504. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00882d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng X, Liang KJ, Tong XG, Ding M, Li DS, Xia CF. Org Lett. 2014;16:3276. doi: 10.1021/ol501287x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Jallabert C, Lapinte C, Riviere H. J Mol Catal. 1980;7:127. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jallabert C, Lapinte C, Riviere H. J Mol Catal. 1982;14:75. [Google Scholar]; (c) Deng Y, Zhang GH, Qi XT, Liu C, Miller JT, Kropf AJ, Bunel EE, Lan Y, Lei AW. Chem Commun. 2015;51:318. doi: 10.1039/c4cc05720a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tnay YL, Chiba S. Chem - Asian J. 2015;10:873. doi: 10.1002/asia.201403196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Rheenen V. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969;10:985. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Paderes MC, Chemler SR. Org Lett. 2009;11:1915. doi: 10.1021/ol9003492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Paderes MC, Chemler SR. Eur J Org Chem. 2011;2011:3679. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201100444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Pettersson-Fasth H, Riesinger SW, Backvall JE. J Org Chem. 1995;60:6091. [Google Scholar]; (b) Riesinger SW, Lofstedt J, Pettersson-Fasth H, Backvall JE. Eur J Org Chem. 1999;1999:3277. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Cossy J, Belotti D, Bellosta V, Brocca D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:6089. [Google Scholar]; (b) Seki Y, Tanabe K, Sasaki D, Sohma Y, Oisaki K, Kanai M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:6501. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.