Abstract

Importance

Prostate cancer treatments are associated with side effects. Understanding the side effects of contemporary approaches to management of localized prostate could inform shared decision-making.

Objective

To compare the harms of radical prostatectomy (RP), radiation (EBRT) and active surveillance (AS).

Design

The Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation (CEASAR) study is a prospective, population-based, cohort study of men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer in 2011–2012. This study reports follow up through August 2015.

Setting

Patients accrued from five Surveillance Epidemiology, and End Results registry sites and the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor.

Participants

Men < 80 years old with clinical stage cT1-2 disease, prostate specific antigen < 50 ng/mL, enrolled within six months of diagnosis, who completed a baseline survey and at least 1 follow-up survey.

Exposure

Treatment with RP, EBRT or AS was ascertained within one year of diagnosis.

Main Outcome and Measures

Patient-reported function in sexual, urinary incontinence, urinary irritative, bowel, and hormonal domains on the 26-item Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) 36 months after enrollment. Domain scores range from 0–100. Higher score indicates better function. Minimum clinically important difference defined as 10–12, 6, 5, 5, and 4, respectively.

Results

The cohort included 2550 men (mean age 63.8 years, 74% white, 55% intermediate or high risk), of whom 1523 (59.7%) underwent RP, 598 (23.5%) EBRT, and 429 (16.8%) AS. Men undergoing EBRT were older (mean age 68.1 vs. 61.5, p<0.001), and had worse baseline sexual function (mean EPIC domain score 52.3 vs. 65.2, p<0.001) than men undergoing RP. At 3 years, adjusted mean sexual domain score for men undergoing RP had declined more than for men undergoing EBRT (mean difference −11.9 points, 95% CI [−15.1, −8.7]). The difference in decline in sexual domain scores between EBRT and AS was not clinically significant (−4.3 points, 95% CI [−9.2, 0.7]). RP was associated with worse urinary incontinence than EBRT (−18.0 points, 95% CI [−20.5, −15.4]) or AS (−12.7 points, 95% CI [−16.0, −9.3]) and better urinary irritative symptoms compared to AS (5.2 points, 95% CI [3.2, 7.2]). No clinically significant differences for bowel or hormone function were noted beyond 12 months. No differences in global quality of life or disease-specific survival (3 deaths) were noted (99.7–100%).

Conclusion and Relevance

In this cohort of men with localized prostate cancer, RP was associated with a larger decline in sexual function and urinary incontinence than EBRT or AS after 3 years, and lesser urinary irritative symptoms compared to AS; however, there were no meaningful differences in bowel or hormonal function beyond 12 months and no meaningful differences in global quality of life measures. These findings may facilitate counseling regarding the comparative harms of contemporary treatments for prostate cancer.

Introduction

The optimal management for localized prostate cancer depends on factors including risk of progression, competing risks of mortality, baseline urinary, sexual and bowel function, and patient preferences.1 Comparing the effectiveness and harms of radiation therapy (RT), surgery (RP) and active surveillance (AS) is critical for shared decision making.2 Yet comparative data have limited generalizability for several reasons, such as focusing on homogenous populations and comparing older treatments instead of contemporary robotic RP and intensity modulated RT (IMRT).3–12

In this context, the Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation (CEASAR) study, a prospective, longitudinal, population-based cohort study was developed.13 In light of the nearly 100% 5-year survival for men with localized prostate cancer, patient-reported disease-specific functional outcomes were selected as the primary short and intermediate-term outcome measures. This study assessed patient-reported functional outcomes at 3 years after treatment.

Methods

The parent study accrued men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer in 2011–12 from 5 Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries (Atlanta, Los Angeles, Louisiana, New Jersey and Utah), and the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor registry. Details of the protocol have been published.13 Eligibility criteria were age < 80 years, PSA < 50 ng/mL, clinical stage T1-T2, no nodal involvement or metastases on clinical evaluation, enrolled within 6 months of diagnosis.

Patient-reported outcomes, were collected via survey at enrollment, and 6, 12, and 36 months after enrollment. A medical chart review, including clinical and treatment information, was obtained at 12 months. SEER registry data were linked to the dataset. This study includes follow-up through August 2015. IRB approval was obtained from each site and Vanderbilt. Patients provided informed consent.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measures were 36-month domain scores on the 26-item Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26), a validated instrument for measuring disease-specific function in sexual, urinary incontinence, urinary irritative, bowel and hormonal domains after treatment for prostate cancer.14 Domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score representing better function. The minimally important difference (MID), representing the magnitude of change that is clinically meaningful to patients, has been estimated for each EPIC domain using standard techniques; the distribution-based approach estimated MID as 1/3-1/2 of a standard deviation and the anchoring approach identified the magnitude of change on each EPIC domain that resulted in a change in satisfaction with treatment.15 Both techniques yielded similar MIDs, and were consistent with the a priori definition of MID used in the power calculation of the original grant application for this study (½ of a standard deviation.) The sexual function domain focuses on the quality and frequency of erections (MID 10–12 points). The urinary incontinence (MID 6 points) and urinary irritative (MID 5 points) domains ask questions about frequency and amount of urinary leakage, and symptoms such as dysuria, hematuria, and urinary frequency. The bowel function domain (MID 4 points) focuses on bowel frequency, urgency, bleeding and pain. The hormonal domain (MID 4 points) assesses symptoms such as hot flashes, gynecomastia, low energy and weight change. Baseline survey instructions were to respond with pre-treatment function in mind. Previous studies have investigated the issue of recall bias for the EPIC, including a study in this cohort, and adjusted differences in domain scores between those who complete the survey before treatment and those who complete it afterward range from 1.0 to 3.7 points, well below the MID for each domain.16

Individual items from the EPIC-26 were selected a priori as secondary outcomes based on clinical relevance by content experts and patients on the study team.

Treatments were also compared with respect to global quality of life, using selected domains from the commonly used Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (SF-36): physical functioning, emotional well-being, and energy/fatigue.17,18 Domain scores are scaled from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function. MIDs for these domains have been estimated for the localized prostate cancer population as 7, 6, and 9 points respectively.19

Exposure

The main exposure was initial treatment (RP, EBRT, or AS), defined according to the following hierarchy of sources: medical chart abstraction, patient report, SEER registry. A participant was categorized as AS if there was documentation of AS in absence of treatment, or if there was no treatment administered within one year of diagnosis. Distinguishing between watchful waiting, AS, and treatment delay was not possible, and these patients were categorized as AS recognizing that it was a heterogeneous group. For analysis, time zero for treated patients was the date of treatment, while for AS patients it was the date of diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared across treatments using Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables.

To describe typical trajectories of function over time, longitudinal regression models were fit to predict EPIC domain scores as a function of treatment, time since treatment, and their interaction. For each domain, a single model was fit incorporating domain scores from all time points. We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an independent weight matrix because of the correlation between observations on the same patients. Modeling time using regression splines allowed for a flexible relationship between function and time. Variability in the interval between treatment and survey completion allowed for estimation of domain scores between rounds of data collection, and beyond 36 months.

Recognizing that outcomes (and patients’ priorities) may differ by baseline function, these models were repeated, stratifying by baseline domain scores (excellent and less than excellent). Since excellent function has not been defined in the literature based on EPIC domain scores, a cutoff baseline score was selected for each domain that approximated the highest quartile of domain scores, an approach that has been used in prior publications on patient-reported outcomes after prostate cancer treatment.20

To measure the association between treatment choice and domain score over time, a similar set of models was fit that adjusted for age, race, comorbidity,21 prostate cancer risk stratum,22 physical function,17,18,23 social support,24 depression,25 medical decision-making style,26 site, and baseline EPIC domain score. This multivariable modeling approach was designed to minimize bias associated with known differences in baseline characteristics that are associated with functional outcomes (i.e., confounding). Multiple imputation was used for missing covariates (see eMethods). Since androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is a standard component of RT for high-risk disease and an option in intermediate-risk disease, ADT was not controlled for in the models.27 Instead, exploratory models were fit for sexual and hormonal function with 5 treatment groups: nerve-sparing RP, non-nerve-sparing RP, EBRT without ADT, EBRT with ADT, and AS. Unadjusted and adjusted longitudinal regression models using GEE were fit for responses to individual EPIC items and for the three SF-36 domains, using the same covariates as above. In the SF-36 regression models, the baseline SF-36 domain score was added as an independent variable.

Probability of overall and disease-specific survival was estimated by treatment using the Kaplan-Meier with log-rank tests.

Differences in domain scores between treatments were statistically significant if the two-tailed p-value was < 0.05 and were interpreted as clinically meaningful if the differences were as large as the MID. R version 3.2.2 was used for all analyses.

Results

The parent study accrued 3,709 men, of whom 440 patients were excluded for failing to meet basic inclusion criteria. An additional 519 men were excluded from the current study for receiving a treatment other than RP, EBRT, or AS, leaving 2,750 patients for consideration (eFigure 1). The analytic cohort contained the 2,550 men (93%) who completed a baseline survey and at least one survey thereafter. Approximately 93% of surveys were completed on paper, while 7% were completed by phone; 98% of surveys were conducted in English and 2% in Spanish; 54% of baseline surveys were collected prior to initial treatment. Survey response rates were 89% at 6 months, 86% at 12 months, and 78% at 36 months (eFigure 1, eTable 1).

Among men in the analytic cohort, 1,523 (59.7%) underwent RP, 598 (23.5%) EBRT and 429 (16.8%) AS. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Briefly, 26% of the cohort was non-white. EBRT patients were older, had higher comorbidity burden, and had higher-risk disease features compared to RP patients. Seventy-seven percent of AS patients were low-risk. Among RP patients with complete reporting of nerve-sparing status (71%, 1082/1523), 79% (859/1082) had bilateral nerve-sparing and among those with complete reporting of surgical approach (85%, 1302/1523), 77% (1002/1302) had robotic surgery. Among EBRT patients with complete records of EBRT type (78%, 467/598), 81% (378/467) had IMRT and among those with complete reporting of ADT use (99%, 593/598), 45% (265/593) of EBRT patients had ADT within the first year. By the 3-year survey, 24.2% of AS patients had undergone treatment, and 90.2% of the remainder had had a PSA checked within the past 12 months.

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics.

| Radical Prostatectomy (N=1523) | External Beam Radiation Therapy (N=598) | Active Surveillance (N=429) | Combined (N=2550) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, Mean (95% CI) | 1523 | 598 | 429 | 2550 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| 61.5 (61.1, 61.8) | 68.1 (67.6, 68.7) | 66.1 (65.4, 66.9) | 63.8 (63.5, 64.1) | ||

|

| |||||

| Race | 1511 | 597 | 427 | 2535 | P=0.02 |

|

| |||||

| White | 1130 (75%) | 421 (71%) | 323 (75%) | 1874 (73%) | |

| Black | 187 (12%) | 110 (18%) | 61 (14%) | 358 (14%) | |

| Hispanic | 125 ( 8%) | 37 ( 6%) | 24 ( 6%) | 186 ( 7%) | |

| Asian | 46 ( 3%) | 22 ( 4%) | 12 ( 3%) | 80 ( 3%) | |

| Other | 23 ( 2%) | 7 ( 1%) | 7 ( 2%) | 37 ( 1%) | |

|

| |||||

| Education | 1441 | 577 | 409 | 2427 | P=0.002 |

|

| |||||

| Less than high school | 130 ( 9%) | 86 (15%) | 33 ( 8%) | 249 (10%) | |

| High school graduate | 302 (21%) | 118 (20%) | 79 (19%) | 499 (21%) | |

| Some college | 315 (22%) | 133 (23%) | 84 (21%) | 532 (22%) | |

| College graduate | 345 (24%) | 118 (20%) | 98 (24%) | 561 (23%) | |

| Graduate/professional school | 349 (24%) | 122 (21%) | 115 (28%) | 586 (24%) | |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | 1438 | 576 | 407 | 2421 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Married | 1192 (83%) | 429 (74%) | 326 (80%) | 1947 (80%) | |

|

| |||||

| Comorbidity Score - Total Illness Burden Indexa | 1448 | 580 | 411 | 2439 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| 0–2 | 481 (33%) | 101 (17%) | 105 (26%) | 687 (28%) | |

| 3–4 | 624 (43%) | 238 (41%) | 162 (39%) | 1024 (42%) | |

| 5 or more | 343 (24%) | 241 (42%) | 144 (35%) | 728 (30%) | |

|

| |||||

| Prostate Cancer Risk Group - D’Amico Classificationb | 1521 | 596 | 427 | 2544 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Low risk | 635 (42%) | 182 (31%) | 327 (77%) | 1144 (45%) | |

| Intermediate Risk | 635 (42%) | 267 (45%) | 81 (19%) | 983 (39%) | |

| High Risk | 251 (17%) | 147 (25%) | 19 ( 4%) | 417 (16%) | |

|

| |||||

| Prostate Specific Antigen (ng/mL) | 1523 | 598 | 429 | 2550 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| 0–4 | 334 (22%) | 85 (14%) | 110 (26%) | 529 (21%) | |

| 4.1–10 | 1018 (67%) | 394 (66%) | 268 (62%) | 1680 (66%) | |

| 10.1–20 | 133 ( 9%) | 86 (14%) | 38 ( 9%) | 257 (10%) | |

| >20 | 38 ( 2%) | 33 ( 6%) | 13 ( 3%) | 84 ( 3%) | |

|

| |||||

| Clinical Stage | 1520 | 597 | 422 | 2539 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| T1c | 1140 (75%) | 436 (73%) | 357 (85%) | 1933 (76%) | |

| T2 | 380 (25%) | 161 (27%) | 65 (15%) | 606 (24%) | |

|

| |||||

| Biopsy Gleason Score | 1519 | 596 | 427 | 2542 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| 3+3 | 744 (49%) | 210 (35%) | 370 (87%) | 1324 (52%) | |

| 3+4 | 458 (30%) | 201 (34%) | 44 (10%) | 703 (28%) | |

| 4+3 | 170 (11%) | 86 (14%) | 7 ( 2%) | 263 (10%) | |

| 8–10 | 147 (10%) | 99 (17%) | 6 ( 1%) | 252 (10%) | |

|

| |||||

| Any Hormone Therapy in the First Year | 1509 | 593 | 391 | 2493 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 75 ( 5%) | 265 (45%) | 3 ( 1%) | 343 (14%) | |

|

| |||||

| Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Compositec Domain Score Mean (95% CI) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Sexual Domain Score | 1447 | 558 | 402 | 2407 | |

|

| |||||

| 65.2 (63.5, 66.9) | 52.3 (49.6, 55.0) | 63.1 (60.0, 66.2) | 61.9 (60.5, 63.2) | P<0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Urinary Incontinence Domain Score | 1467 | 575 | 409 | 2451 | |

|

| |||||

| 86.7 (85.5, 87.8) | 88.2 (86.7, 89.6) | 88.7 (87.0, 90.4) | 87.4 86.6, 88.2) | P=0.878 | |

|

| |||||

| Urinary Irritative Domain Score | 1463 | 574 | 409 | 2446 | |

|

| |||||

| 83.2 (82.3, 84.1) | 82.3 (80.9, 83.7) | 83.9 (82.3, 85.5) | 83.1 (82.4, 83.8) | P=0.098 | |

|

| |||||

| Bowel Domain Score | 1492 | 585 | 415 | 2492 | |

|

| |||||

| 94.0 (93.3, 94.6) | 93.4 (92.5, 94.3) | 94.0 (92.8, 95.2) | 93.8 (93.4, 94.3) | P=0.02 | |

|

| |||||

| Hormonal Domain Score | 1467 | 563 | 412 | 2442 | |

|

| |||||

| 89.8 (89.1, 90.5) | 86.7 (85.3, 88.0) | 89.7 (88.3, 91.1) | 89.1 (88.5, 89.6) | P<0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36d Domain Score Mean (95% CI) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Physical Function Score | 1477 | 577 | 405 | 2459 | |

|

| |||||

| 87.9 (86.9, 88.9) | 78.3 (76.2, 80.3) | 84.0 (81.6, 86.4) | 85.0 (84.1, 85.9) | P<0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Emotional Well-Being Score | 1515 | 592 | 426 | 2533 | |

|

| |||||

| 78.0 (77.1, 78.9) | 79.2 (77.7, 80.7) | 80.5 (78.9, 82.1) | 78.7 (78.0, 79.4) | P=0.103 | |

|

| |||||

| Energy/Fatigue Score | 1477 | 577 | 405 | 2459 | |

|

| |||||

| 72.4 (71.4, 73.4) | 68.3 (66.7, 70.0) | 71.5 (69.7, 73.4) | 71.3 (70.5, 72.1) | P<0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Medical Outcomes Study Modified Social Support Scale Scoree Mean (95% CI) | 1515 | 592 | 426 | 2533 | |

|

| |||||

| 81.2 (79.8, 82.6) | 79.0 (76.7, 81.3) | 80.5 (77.9 83.1) | 80.6 (79.5, 81.7) | P=0.103 | |

|

| |||||

| Center for Epidemiologic Studiesf Mean (95% CI) | 1490 | 582 | 415 | 2487 | P=0.107 |

|

| |||||

| Depression Scale Score | 20.2 (19.3, 21.2) | 20.9 (19.2, 22.5) | 18.1 (16.4, 20.0) | 20.0 (19.3, 20.8) | |

|

| |||||

| Medical Decision-Making Style Scoreg Mean (95% CI) | 1504 | 585 | 411 | 2500 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| 78.7(77.7, 79.7) | 72.7 (70.7, 74.7) | 76.7 (74.4, 79.0) | 77.0 (76.1, 77.8) | ||

|

| |||||

| Accrual Site | 1523 | 598 | 429 | 2550 | P<0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Louisiana | 392 (26%) | 219 (37%) | 108 (25%) | 719 (28%) | |

| Utah | 127 ( 8%) | 18 ( 3%) | 60 (14%) | 205 ( 8%) | |

| Atlanta | 195 (13%) | 55 ( 9%) | 58 (14%) | 308 (12%) | |

| Los Angeles County | 444 (29%) | 145 (24%) | 138 (32%) | 727 (29%) | |

| New Jersey | 243 (16%) | 135 (23%) | 32 ( 7%) | 410 (16%) | |

| Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urolgoic Research Endeavor (CaPSURE) | 122 ( 8%) | 26 ( 4%) | 33 ( 8%) | 181 ( 7%) | |

Total Illness Burden Index for Prostate Cancer (TIBI CaP) is a validated measure of comorbidity and predictor of all-cause mortality in a prostate cancer population. Scores range from 0 to 23, with higher score indicating a higher number and/or greater severity of comorbid illnesses.

D’Amico risk classification system predicts the risk of recurrence after treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. Low-risk disease is defined as a clinical stage T2a or less, Gleason Score 6 (3+3) or less, and a prostate-specific antigen less than 10 ng/mL. High-risk disease is defined as T2c or higher, Gleason Score 8 (3+5, 4+4, 5+3) or greater, or a prostate-specific antigen greater than 20 ng/mL. Disease not defined as low or high-risk is defined as intermediate-risk.

The 26-item Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite assesses sexual, urinary, bowel and hormonal function, and domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better function.

The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a 36-item patient-reported survey of patient health consisting of 8 domains. The physical function domain score is a weighted sum of 10 questions on the SF-36 (items 3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12). The emotional well-being domain score is a weighted sum of 5 items on the SF-36 (items 24, 25, 26, 28, 30). The energy/fatigue score is a weighted sum of 4 questions on the SF-36 (items 23, 27, 29, 31). Each domain score is directly transformed to a scale of 0–100 with increasing scores indicating better function or less disability.

Five selected questions from the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey were used to create a modified domain score. Responses were directly transformed to a scale of 0–100 with increasing scores indicating greater support.

The depression scale score is derived using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Scores were scaled to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

The Medical Decision Making Style Score is a validated measure of participatory decision making, using 7 items, scored on a scale from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating increased patient choice, control, and responsibility.

For the stratified analyses, excellent baseline EPIC domain scores were defined as ≥ 90 for the sexual function domain (26.4% of men); 100 for the urinary incontinence domain (60.3%); 100 for the urinary irritative domain (26.1%); 100 for the bowel domain (61.7%); and 100 for the hormonal domain (39.1%).

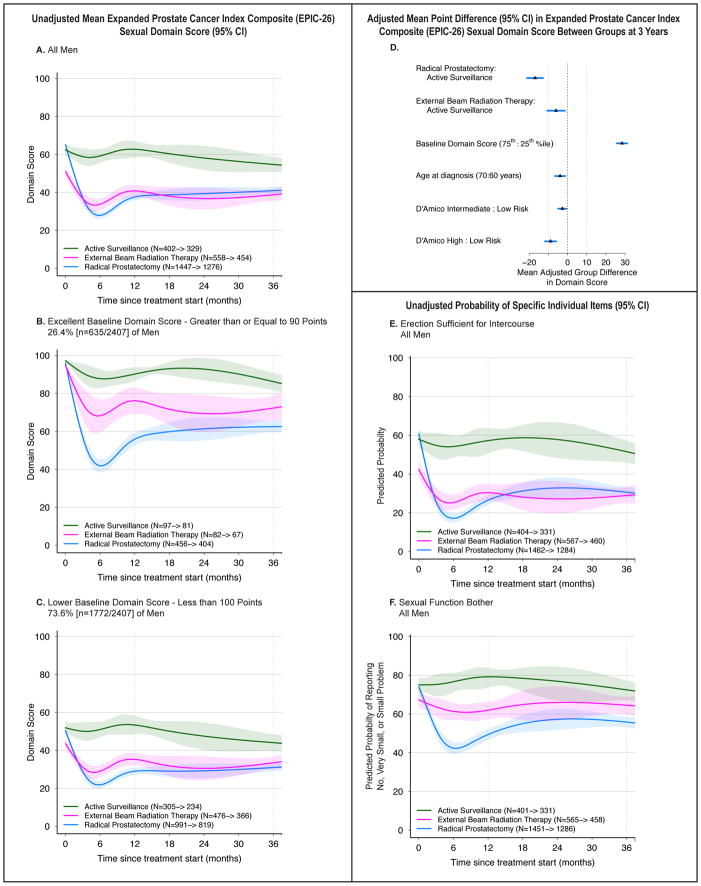

Sexual Function

Men undergoing RP had higher baseline sexual domain scores than men undergoing EBRT, and comparable scores to those on AS (eTable 2). RP and EBRT were associated with declines in sexual function scores, but the decline was greater for RP patients, resulting in similar average unadjusted domain score for RP and EBRT at 3 years (Figure 1A–C). The difference in functional decline between RP and EBRT was greater for the 26.4% of men with excellent baseline function (baseline sexual domain score ≥ 90), while the 73.6% of men with lower baseline function (baseline domain score < 90) had poor sexual function outcomes regardless of whether they underwent RP or EBRT. AS was associated with preservation of function, with mild decline over time.

Figure 1.

Association Between Treatment and Sexual Function Outcomes. Outcomes are sexual function domain scores and selected individual items from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26). Domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score representing better function. Time zero is the date of treatment for radical prostatectomy and external beam radiation therapy patients, and date of diagnosis for active surveillance patients. Minimum clinically important difference for the sexual domain score is 10 points. Individual item probabilities range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing a higher probability of favorable outcome. Numbers in the legends indicate the number of men who completed baseline and 36-month sexual domain surveys for each treatment group. Longitudinal figures extend to 37 months along the x-axis because the interval between treatment and completion of the 36-month survey was greater than 36 months for some patients.

A–C: Unadjusted Mean Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Sexual Domain Score (95% CI), Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men (panel A), Men with Excellent Baseline Domain Score (panel B), and Men with Lower Baseline Domain Score (panel C). A baseline domain score of 90 or above was defined as excellent, and a score below 90 was defined as lower, approximating subgroups of the top quartile and all others.

D: Adjusted Mean Point Difference (95% CI) in Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Sexual Domain Score Between Groups at 3 Years. Forest plots depict the covariate adjusted effect of treatment, baseline sexual domain score, age, and D’Amico risk stratum on domain score at 3 years, estimated from multivariable regression models that controlled for baseline domain score, age, race, comorbidity, prostate cancer risk group, physical function, social support, depression, medical decision-making style and accrual site. Effect size represents the adjusted mean point difference on the EPIC domain score between groups; the group after the colon (:) is the referent, so positive values may be interpreted as better outcome for the group before the colon and negative values indicate a better outcome for the group after the colon. Reference lines indicate the minimum clinically important difference (10 points). eTable 8 contains unadjusted domain scores and number of patients for each subgroup (age, baseline domain score and disease risk group) by treatment. D’Amico risk classification system predicts the risk of recurrence after treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. Low-risk disease is defined as a clinical stage T2a or less, Gleason Score 6 (3+3) or less, and a prostate-specific antigen less than 10 ng/mL. High-risk disease is defined as T2c or higher, Gleason Score 8 (3+5, 4+4, 5+3) or greater, or a prostate-specific antigen greater than 20 ng/mL. Disease not defined as low or high-risk is defined as intermediate-risk.

E: Unadjusted Probability of Reporting Erection Sufficient for Intercourse, Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men. This individual item from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) was selected a priori as a secondary outcome based on its clinical relevance.

F. Unadjusted Probability of Reporting No, Very Small or Small Problem with Sexual Function Bother, Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men. This individual item from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) was selected a priori as a secondary outcome based on its clinical relevance.

When controlling for baseline domain scores and other covariates (eTable 2, Figure 1D), men undergoing RP had a larger decline in sexual domain score compared with EBRT (adjusted mean domain score difference at 3 years: −11.9 points, 95% CI −15.1, −8.7) or AS (−16.2 [−20.6, −11.7]), relative to the MID of 10–12. Adjusted domain score after EBRT was significantly worse than AS at 12 months (−10.5, [−14.0, −6.9]), but the magnitude of difference at 3 years was no longer significant (−4.3, [−9.2, 0.7]). Treatment, baseline domain score and time since treatment were the only variables for which the magnitude of association with 3-year domain score exceeded the MID.

On exploratory analysis with a 5-tier treatment variable (nerve-sparing RP, non-nerve sparing RP, EBRT alone, EBRT + ADT, and AS), the difference between EBRT alone and AS was not statistically significant (−3.0 points, p = 0.27), and the difference between RP and EBRT + ADT was attenuated (−8.2 points [−13.2, −3.2]), below the MID (eFigure 2).

More men who underwent RP were bothered by sexual dysfunction 3 years after diagnosis (44% vs. 35% for EBRT and 28% for AS, p<0.001 on multivariable analysis; Figure 1E, eTable 2). Erection insufficient for intercourse was common at 3 years (70% for RP, 71% for EBRT, and 51% for AS on raw percentages [Figure 1F]), but, controlling for baseline sexual function and other factors, odds were significantly higher for RP vs. AS (OR 3.4, 95% CI [2.5, 4.6]) and RP vs. EBRT (2.1, 95% CI [1.5, 2.9]). Among men who had sufficient erections at baseline, erection sufficient for intercourse at 3 years was reported in 43% (95% CI: 40, 47) for RP, 53% (45, 60) for EBRT and 75% (68, 80) for AS in raw percentages. An exploratory multivariable model, using 5 treatment groups, yielded similar results (eTable 3).

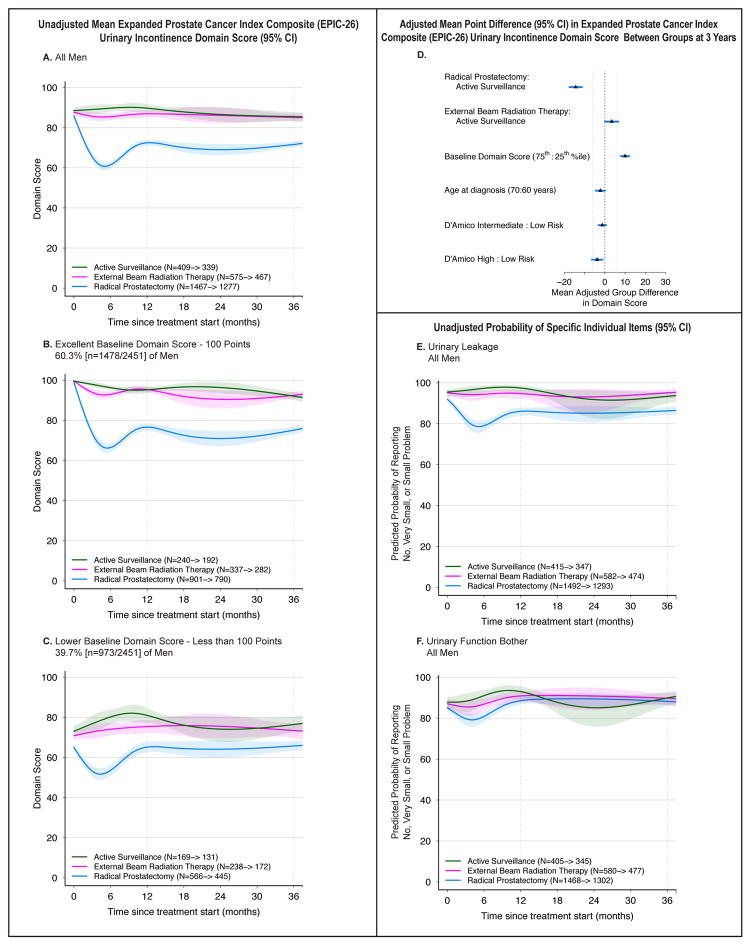

Urinary Incontinence

Baseline urinary incontinence domain scores were similar across groups (eTable 4). However, RP was associated with a significant decline in urinary incontinence score after treatment, particularly in the 60.3% of men with perfect urinary incontinence domain scores at baseline (Figure 2A–C). There was no significant change in urinary incontinence score for men who had EBRT or AS, regardless of baseline score.

Figure 2.

Association Between Treatment and Urinary Incontinence Outcomes. Outcomes are urinary incontinence domain scores and selected individual items from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26). Domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score representing better function. Time zero is the date of treatment for radical prostatectomy and external beam radiation therapy patients, and date of diagnosis for active surveillance patients. Minimum clinically important difference for the urinary incontinence domain score is 6 points. Individual item probabilities range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing a higher probability of favorable outcome. Numbers in the legends indicate the number of men who completed baseline and 36-month urinary incontinence domain surveys for each treatment group. Longitudinal figures extend to 37 months along the x-axis because the interval between treatment and completion of the 36-month survey was greater than 36 months for some patients.

A–C: Unadjusted Mean Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Urinary Incontinence Domain Score (95% CI), Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men (panel A), Men with Excellent Baseline Domain Score (panel B), and Men with Lower Baseline Domain Score (panel C). A baseline domain score of 100 or above was defined as excellent, and a score below 100 was defined as lower, approximating subgroups of the top quartile and all others.

D: Adjusted Mean Point Difference (95% CI) in Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Urinary Incontinence Domain Score Between Groups at 3 Years. Forest plots depict the covariate adjusted effect of treatment, baseline urinary incontinence domain score, age, and D’Amico risk stratum on domain score at 3 years, estimated from multivariable regression models that controlled for baseline domain score, age, race, comorbidity, prostate cancer risk group, physical function, social support, depression, medical decision-making style and accrual site. Effect size represents the adjusted mean point difference on the EPIC domain score between groups; the group after the colon (:) is the referent, so positive values may be interpreted as better outcome for the group before the colon and negative values indicate a better outcome for the group after the colon. Reference lines indicate the minimum clinically important difference (6 points). eTable 8 contains unadjusted domain scores and number of patients for each subgroup (age, baseline domain score and disease risk group) by treatment. D’Amico risk classification system predicts the risk of recurrence after treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. Low-risk disease is defined as a clinical stage T2a or less, Gleason Score 6 (3+3) or less, and a prostate-specific antigen less than 10 ng/mL. High-risk disease is defined as T2c or higher, Gleason Score 8 (3+5, 4+4, 5+3) or greater, or a prostate-specific antigen greater than 20 ng/mL. Disease not defined as low or high-risk is defined as intermediate-risk.

E: Unadjusted Probability of Reporting No, Very Small or Small Problem with Urinary Leakage, Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men. This individual item from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) was selected a priori as a secondary outcome based on its clinical relevance.

F. Unadjusted Probability of Reporting No, Very Small or Small Problem with Urinary Function Bother, Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men. This individual item from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) was selected a priori as a secondary outcome based on its clinical relevance.

Despite some improvement in incontinence domain scores 12 months after RP, adjusted incontinence scores were still significantly worse for RP compared with AS (−12.7 points [−16.0, −9.3]) and EBRT (−18.0 points [−20.5, −15.4]) at 3 years, differences greater than the MID (6 points) (Figure 2D, eTable 4). By contrast, urinary incontinence was not significantly different between EBRT and AS. Treatment, baseline domain score and time since treatment were the only variables for which the magnitude of association with the 3-year domain score exceeded the MID.

Reports of moderate or big problem with urinary leakage were more common after RP vs. AS (14% vs. 6%, OR 2.9 [1.8, 4.7]) and RP vs. EBRT (14% vs. 5%, OR 4.5 [2.7, 7.3]) (Figure 2E, eTable 4). Urinary function bother scores were not significantly different for RP vs. AS and EBRT vs. AS at 3 years, but were higher for RP vs. EBRT (12% vs. 10%, OR 1.7 [1.1, 2.5]) (Figure 2F, eTable 4).

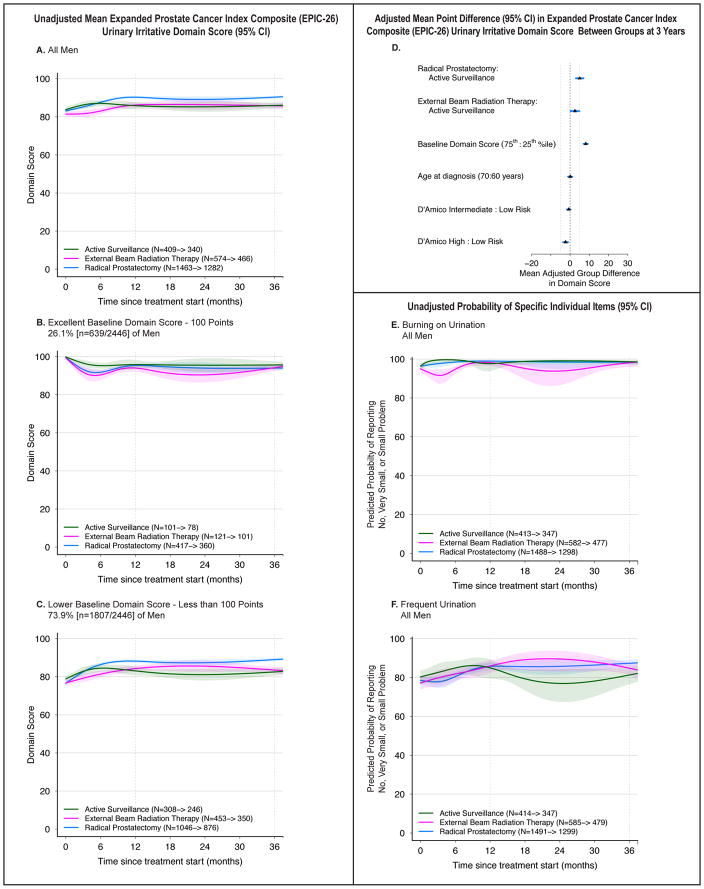

Urinary Irritative

Baseline scores were similar across groups (eTable 4). Scores improved for RP patients, particularly in the 73.9% of men whose baseline score was below 100 (Figure 3A–C). Those undergoing EBRT or AS experienced little or no change in irritative urinary symptoms.

Figure 3.

Association Between Treatment and Urinary Irritative Outcomes. Outcomes are urinary irritative domain scores and selected individual items from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26). Domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score representing better function. Time zero is the date of treatment for radical prostatectomy and external beam radiation therapy patients, and date of diagnosis for active surveillance patients. Minimum clinically important difference for the urinary irritative domain score is 5 points. Individual item probabilities range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing a higher probability of favorable outcome. Numbers in the legends indicate the number of men who completed baseline and 36-month urinary irritative domain surveys for each treatment group. Longitudinal figures extend to 37 months along the x-axis because the interval between treatment and completion of the 36-month survey was greater than 36 months for some patients.

A–C: Unadjusted Mean Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Urinary Irritative Domain Score (95% CI), Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men (panel A), Men with Excellent Baseline Domain Score (panel B), and Men with Lower Baseline Domain Score (panel C). A baseline domain score of 100 or above was defined as excellent, and a score below 100 was defined as lower, approximating subgroups of the top quartile and all others.

D: Adjusted Mean Point Difference (95% CI) in Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Urinary Irritative Domain Score Between Groups at 3 Years. Forest plots depict the covariate adjusted effect of treatment, baseline urinary Irritative domain score, age, and D’Amico risk stratum on domain score at 3 years, estimated from multivariable regression models that controlled for baseline domain score, age, race, comorbidity, prostate cancer risk group, physical function, social support, depression, medical decision-making style and accrual site. Effect size represents the adjusted mean point difference on the EPIC domain score between groups; the group after the colon (:) is the referent, so positive values may be interpreted as better outcome for the group before the colon and negative values indicate a better outcome for the group after the colon. Reference lines indicate the minimum clinically important difference (5 points). eTable 8 contains unadjusted domain scores and number of patients for each subgroup (age, baseline domain score and disease risk group) by treatment. D’Amico risk classification system predicts the risk of recurrence after treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. Low-risk disease is defined as a clinical stage T2a or less, Gleason Score 6 (3+3) or less, and a prostate-specific antigen less than 10 ng/mL. High-risk disease is defined as T2c or higher, Gleason Score 8 (3+5, 4+4, 5+3) or greater, or a prostate-specific antigen greater than 20 ng/mL. Disease not defined as low or high-risk is defined as intermediate-risk.

E: Unadjusted Probability of Reporting No, Very Small or Small Problem with Burning on Urination, Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men. This individual item from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) was selected a priori as a secondary outcome based on its clinical relevance.

F. Unadjusted Probability of Reporting No, Very Small or Small Problem with Frequent Urination, Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men. This individual item from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) was selected a priori as a secondary outcome based on its clinical relevance.

Adjusted urinary irritative function scores were slightly better for men undergoing RP compared to AS at 1 year (4.5 points [3.0, 6.0]) and 3 years (5.2 points [3.2, 7.2]), at the threshold of clinical significance (eTable 4). Other comparisons across treatments, while statistically significant, were below the MID of 5 (Figure 3D, eTable 4). Besides treatment with RP, the only other factors for which the magnitude of association with 3-year domain score exceeded the MID were baseline domain score and time since treatment.

Reports of moderate or big problems with burning with urination were uncommon (2% in each group [Figure 3E, eTable 4]). Reports of moderate or big problem with frequent urination were lower for RP vs. AS (13% vs. 18%, OR 0.6 [0.4, 0.8]) and for EBRT vs. AS (15% vs. 18%, OR 0.6 [0.4, 0.8]) at 3 years, but not significantly different between RP and EBRT (Figure 3F, eTable 4).

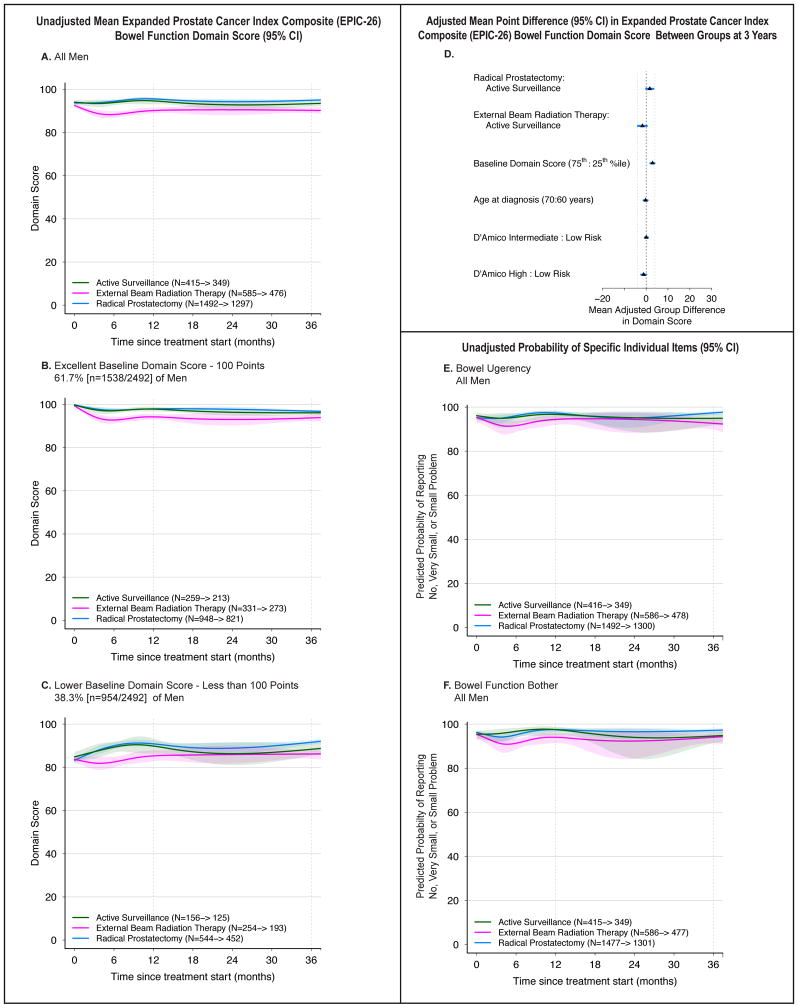

Bowel Function

Decline in bowel domain score was not common (Figure 4A–C, eTable 5). Six months after treatment, domain scores were higher in men who underwent RP vs. EBRT (4.6 points [3.2, 6.1]) and lower for EBRT vs. AS (−5.8 points [−10.3, −1.2]). However, by 12 months these differences were near the MID of 4 and by 36 months, they were smaller. Unadjusted and adjusted results were similar. No other independent variables had a magnitude of association with 3-year domain score that met the threshold for clinical significance.

Figure 4.

Association Between Treatment and Bowel Function Outcomes. Outcomes are bowel function domain scores and selected individual items from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26). Domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score representing better function. Time zero is the date of treatment for radical prostatectomy and external beam radiation therapy patients, and date of diagnosis for active surveillance patients. Minimum clinically important difference for the bowel function domain score is 4 points. Individual item probabilities range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing a higher probability of favorable outcome. Numbers in the legends indicate the number of men who completed baseline and 36-month bowel function domain surveys for each treatment group. Longitudinal figures extend to 37 months along the x-axis because the interval between treatment and completion of the 36-month survey was greater than 36 months for some patients.

A–C: Unadjusted Mean Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Bowel Function Domain Score (95% CI), Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men (panel A), Men with Excellent Baseline Domain Score (panel B), and Men with Lower Baseline Domain Score (panel C). A baseline domain score of 100 or above was defined as excellent, and a score below 100 was defined as lower, approximating subgroups of the top quartile and all others.

D: Adjusted Mean Point Difference (95% CI) in Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Bowel Function Domain Score Between Groups at 3 Years. Forest plots depict the covariate adjusted effect of treatment, baseline bowel function domain score, age, and D’Amico risk stratum on domain score at 3 years, estimated from multivariable regression models that controlled for baseline domain score, age, race, comorbidity, prostate cancer risk group, physical function, social support, depression, medical decision-making style and accrual site. Effect size represents the adjusted mean point difference on the EPIC domain score between groups; the group after the colon (:) is the referent, so positive values may be interpreted as better outcome for the group before the colon and negative values indicate a better outcome for the group after the colon. Reference lines indicate the minimum clinically important difference (4 points). eTable 8 contains unadjusted domain scores and number of patients for each subgroup (age, baseline domain score and disease risk group) by treatment. D’Amico risk classification system predicts the risk of recurrence after treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. Low-risk disease is defined as a clinical stage T2a or less, Gleason Score 6 (3+3) or less, and a prostate-specific antigen less than 10 ng/mL. High-risk disease is defined as T2c or higher, Gleason Score 8 (3+5, 4+4, 5+3) or greater, or a prostate-specific antigen greater than 20 ng/mL. Disease not defined as low or high-risk is defined as intermediate-risk.

E: Unadjusted Probability of Reporting No, Very Small or Small Problem with Bowel Urgency, Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men. This individual item from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) was selected a priori as a secondary outcome based on its clinical relevance.

F. Unadjusted Probability of Reporting No, Very Small or Small Problem with Bowel Function Bother, Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men. This individual item from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) was selected a priori as a secondary outcome based on its clinical relevance.

The frequency of ‘moderate or big problem’ with bowel bother, bloody stools, or bowel urgency was 1–8% across all treatments at 3 years (Figure 4E–F, eTable 5). Nonetheless, the odds of bowel urgency at 3 years were lower for RP than EBRT (3% vs. 7%, OR 0.3 [0.2, 0.6]) and RP vs. AS (3% vs. 5%, OR 0.5 [0.3, 0.9]).

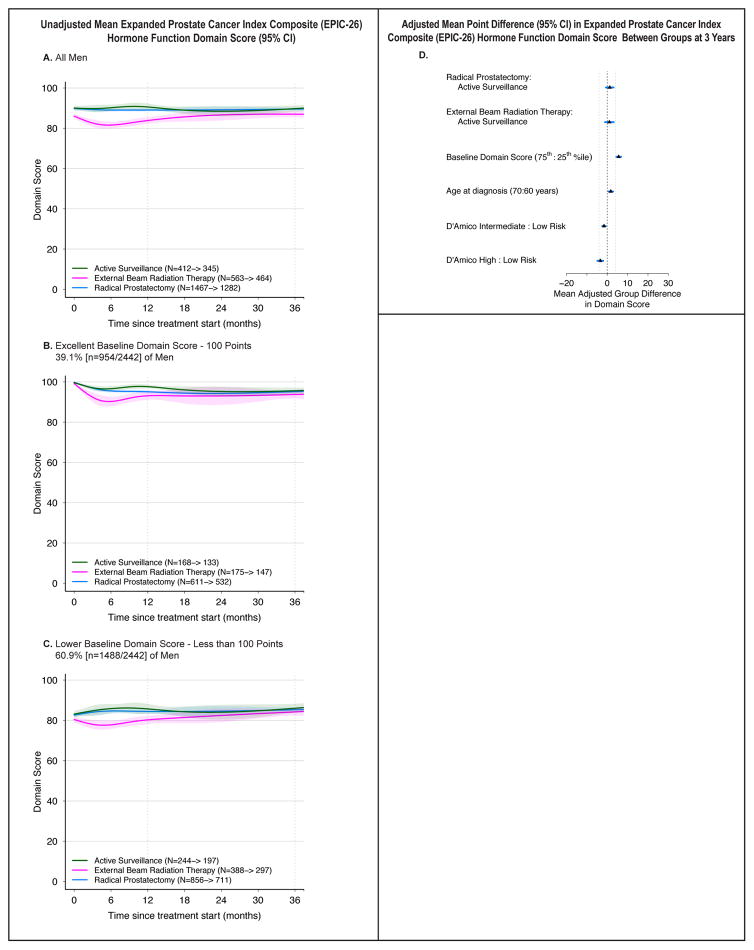

Hormone Function

Hormone domain scores were worse for EBRT compared to AS and RP at 6 months (RP vs. EBRT: 5.0 points [3.3, 6.6]; EBRT vs. AS: −6.5 points [−11.1, −1.9]), but these differences no longer significant at 3 years on unadjusted or adjusted analyses (Figure 5, eTable 6). No other independent variables had a magnitude of association with 3-year domain score that reached the MID.

Figure 5.

Association Between Treatment and Hormone Function Outcomes. Outcomes are hormone function domain scores from the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26). Domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score representing better function. Time zero is the date of treatment for radical prostatectomy and external beam radiation therapy patients, and date of diagnosis for active surveillance patients. Minimum clinically important difference for the bowel function domain score is 4 points. Numbers in the legends indicate the number of men who completed baseline and 36-month hormone function domain surveys for each treatment group. Longitudinal figures extend to 37 months along the x-axis because the interval between treatment and completion of the 36-month survey was greater than 36 months for some patients.

A–C: Unadjusted Mean Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Hormone Function Domain Score (95% CI), Longitudinally by Treatment in All Men (panel A), Men with Excellent Baseline Domain Score (panel B), and Men with Lower Baseline Domain Score (panel C). A baseline domain score of 100 or above was defined as excellent, and a score below 100 was defined as lower, approximating subgroups of the top quartile and all others.

D: Adjusted Mean Point Difference (95% CI) in Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) Hormone Function Domain Score Between Groups at 3 Years. Forest plots depict the covariate adjusted effect of treatment, baseline hormone function domain score, age, and D’Amico risk stratum on domain score at 3 years, estimated from multivariable regression models that controlled for baseline domain score, age, race, comorbidity, prostate cancerrisk group, physical function, social support, depression, medical decision-making style and accrual site. Effect size represents the adjusted mean point difference on the EPIC domain score between groups; the group after the colon (:) is the referent, so positive values may be interpreted as better outcome for the group before the colon and negative values indicate a better outcome for the group after the colon. Reference lines indicate the minimum clinically important difference (4 points). eTable 8 contains unadjusted domain scores and number of patients for each subgroup (age, baseline domain score and disease risk group) by treatment. D’Amico risk classification system predicts the risk of recurrence after treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. Low-risk disease is defined as a clinical stage T2a or less, Gleason Score 6 (3+3) or less, and a prostate-specific antigen less than 10 ng/mL. High-risk disease is defined as T2c or higher, Gleason Score 8 (3+5, 4+4, 5+3) or greater, or a prostate-specific antigen greater than 20 ng/mL. Disease not defined as low or high-risk is defined as intermediate-risk.

In the exploratory models that separated EBRT into with and without ADT, the only group with decrements in hormone function was the EBRT + ADT group, and these associations were limited to the first year (eFigure 2).

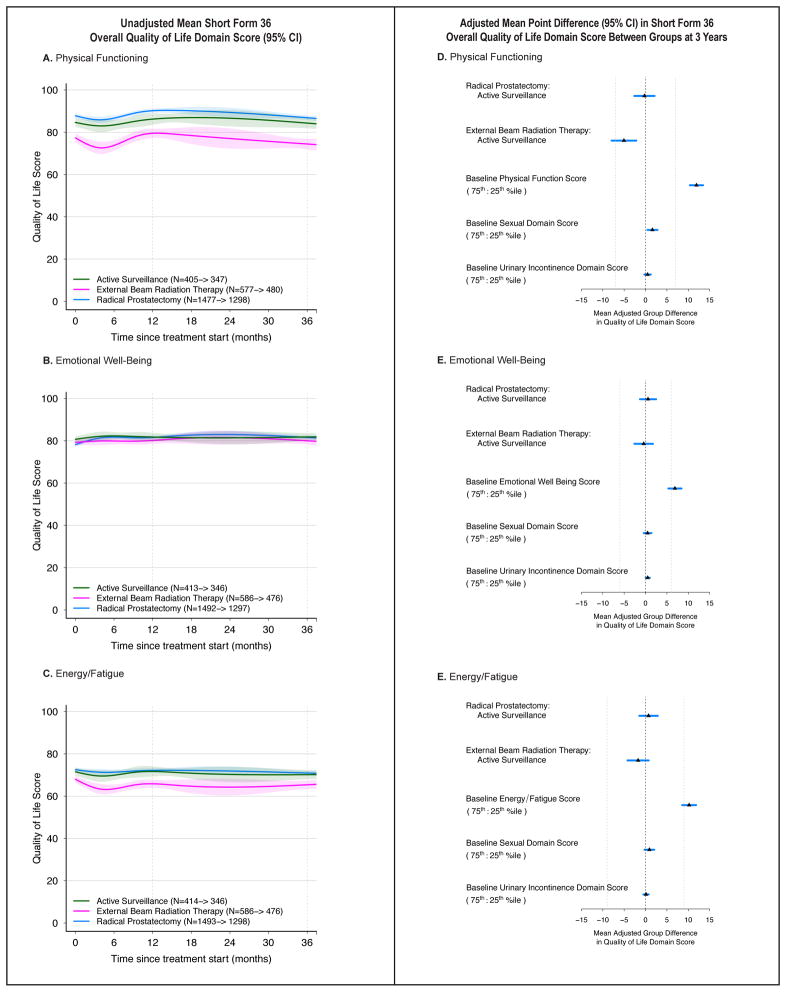

Quality of life

Baseline Physical Functioning and Energy/Fatigue scores on the SF-36 were lower for men undergoing EBRT compared to RP or AS (Figure 6, eTable 7). None of the treatment groups experienced a clinically significant decline in Physical Functioning, Emotional Well-Being, or Energy/Fatigue scores. On multivariable analysis, associations between treatment and 3-year SF-36 quality of life domain scores were below the threshold for clinical significance, as were associations baseline EPIC sexual and urinary incontinence domain scores and 3-year SF-36 domain scores.

Figure 6.

Association Between Treatment and Overall Quality of Life Outcomes. Outcomes are domain scores on the Short Form-36 (physical function, emotional well-being and energy/fatigue). Domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score representing better function or less disability. Time zero is the date of treatment for radical prostatectomy and external beam radiation therapy patients, and date of diagnosis for active surveillance patients. Numbers in the legends indicate the number of men who completed baseline and 36-month hormone function domain surveys for each treatment group. Longitudinal figures extend to 37 months along the x-axis because the interval between treatment and completion of the 36-month survey was greater than 36 months for some patients.

A–C: Unadjusted Mean Short-Form 36 Overall Quality of Life Domain Scores (95% CI), Longitudinally by Treatment. Physical Function (panel A); Emotional Well-Being (panel B); and Energy/Fatigue (panel C).

D–F: Adjusted Mean Point Difference (95% CI) in Short Form 36 (SF-36) Overall Quality of Life Domain Scores Between Groups at 3 Years. Forest plots depict the covariate adjusted effect of treatment, baseline SF-36 domain score, and baseline Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite -26 (EPIC-26) sexual and urinary incontinence domain scores, and on SF-36 domain score at 3 years, estimated from multivariable regression models that controlled for age, race, comorbidity, prostate cancer risk group, physical function, social support, depression, medical decision-making style and accrual site. Effect size represents the adjusted mean point difference on the SF-36 domain score between groups; the group after the colon (:) is the referent, so positive values may be interpreted as better outcome for the group before the colon and negative values indicate a better outcome for the group after the colon. Reference lines indicate the minimum clinically important difference for each domain (7 points for Physical Functioning, 6 points for Emotional Well-Being, and 9 points for Energy/Fatigue). eTable 8 contains unadjusted domain scores and number of patients for each subgroup (age, baseline domain score and disease risk group) by treatment.

Survival

Median follow up time among censored patients was 40 months (Q1, Q3: 38, 45). There were 78 deaths, including 3 prostate cancer deaths. On Kaplan-Meier analysis, estimated 3-year disease-specific survival was not significantly different across groups (99.7–100%). Unadjusted 3-year overall survival was higher for RP (99% [98, 99]) compared to other groups (EBRT: 96% [94, 98]; AS: 97% [95, 99], p<0.001), commensurate with the younger age and lower comorbidity of men undergoing RP (eTable 9).

Discussion

In this study of men with localized prostate cancer, RP was associated with clinically significant declines in sexual function compared to EBRT and AS, particularly in men with excellent function at baseline. Urinary incontinence scores also declined significantly after surgery compared to EBRT and AS, with 14% of RP patients reporting a moderate or big problem with urinary leakage at 3 years, compared to 5% with EBRT and 6% with AS. RP was associated with better irritative voiding symptoms than AS, with a difference that met the threshold for clinical significance. Mean scores in bowel and hormonal domains were significantly worse for EBRT vs. RP and AS at 6 months, but the differences were below threshold for clinical significance by 3 years. Treatment, baseline domain scores and time since treatment were the independent variables with clinically significant associations with 3-year domain scores. None of the treatment groups experienced clinically significant declines in global quality of life domain scores. This information may facilitate patient counseling regarding the expected harms of contemporary treatments, and their possible impact on quality of life.

Prior studies have quantified the harms of prostate cancer treatment. However, randomized trials in localized prostate cancer have been difficult to execute, and those that have been completed focus on outmoded treatments; enrolled too few minority patients; lack a range of disease severity; failed to collect baseline functional assessments; or include a preponderance of elderly, infirm patients and/or low-risk patients, for whom treatment is questionable.3,5,6,28–30 The ProtecT trial, for example, included 99% Caucasian patients and nearly 80% Gleason 6 (low-risk) patients.5,6 In ProtecT, 87% of surgical patients underwent open RP (compared to 77% robotic in this study) and patients undergoing EBRT had 3D conformal RT plus ADT (compared to 81% IMRT, with 45% receiving concurrent ADT in this study).5,6 Thus, ProtecT study findings may be difficult to apply to a racially diverse population with a range of disease risk strata, managed with contemporary treatments.

Case series that have evaluated functional outcomes are not generalizable because they report on outcomes at centers of excellence; lack the variables necessary to adjust for confounding; lack an AS group as a comparator; or have other sources of bias.31–37

Despite these caveats, functional outcomes in this study are similar to previously published multi-institutional prospective cohort studies, and the ProtecT trial.6,20,38–41 Nonetheless, comparisons between the CEASAR cohort and similar historical cohorts have shown slightly smaller declines in erectile function domain scores at 6 and 12 months with robotic RP compared with open RP, and slightly better bowel domain scores at 6 months for IMRT compared to older 3D conformal RT.42,43 These data suggest that contemporary treatments have similar associations with functional outcomes, but perhaps slightly less in magnitude.

This study may have implications for decision making in localized prostate cancer. First, it demonstrates the frequency and severity of side effects of contemporary treatments, and the likelihood of preserved global quality of life regardless of treatment, thus providing a basis for shared decision-making. Secondly, in contrast to previously published studies, this study may be more generalizable, since the cohort is racially diverse, population based, and includes a range of disease severity.3,6,28,38 Third, this study may inform future research on personalized risk assessment; tools to facilitate shared decision making; and other patient-centered outcomes.

This study has several limitations. There may be disagreement about the definition of MID, which may also differ from one patient to the next. While some outcomes favored one treatment over another, the results do not indicate what value patients place on particular domains. Furthermore, there are other important outcomes to consider in localized prostate cancer, including long-term functional outcomes and oncologic endpoints, anxiety, satisfaction, and financial toxicity. The number and severity of adverse outcomes presenting beyond 3 years may differ by treatment, and 3 years is inadequate to estimate oncologic outcomes. Data on patients who had alternative treatments, such as brachytherapy and ablation, were not included because there were not enough patients who received these treatments to generate sufficient statistical power for reliable comparisons. Aggregated data and average function scores may fail to capture the severity of side effects for individuals, and do not yield personalized risk estimates. The analysis did not adjust for the quality of care or experience of the treating provider or institution, which may influence outcomes. Thus, the findings of this study represent a sub-set of the information needed to guide decision making. A substantial proportion of patients answered the baseline survey after initiating treatment, raising the possibility of recall bias, although in prior studies the magnitude of recall bias was small for the EPIC.16 This study used an observational cohort, rather than an experimental design, so there may be unmeasured sources of confounding.

Conclusion

In this cohort of men with localized prostate cancer, RP was associated with a larger decline in sexual function and urinary incontinence than EBRT or AS after 3 years, and lesser urinary irritative symptoms compared to AS; however, there were no meaningful differences in bowel or hormonal function beyond 12 months and no meaningful differences in global quality of life measures. These findings may facilitate counseling regarding the comparative harms of contemporary treatments for prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

What are the comparative harms of contemporary treatments for localized prostate cancer?

Findings

In this prospective, population-based cohort study of 2,550 men, radical prostatectomy was associated with significant declines in sexual function compared with external beam radiotherapy (−11.9 points on a 100-point scale) and active surveillance (−16.2 points) at 3 years. Radical prostatectomy was also associated with significant declines in urinary incontinence compared to radiation and active surveillance, but there were no meaningful differences in bowel or hormonal function beyond 12 months, and no meaningful differences in global quality of life.

Meaning

Quantifying the harms of different treatment options may facilitate treatment counseling in men with localized prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

Daniel A. Barocas and David F. Penson had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

JoAnn M. Alvarez and Tatsuki Koyama conducted and are responsible for the data analysis.

None of the authors has any relevant financial interests, activities, relationships or affiliations pertaining to this study.

Funding for the study was provided by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R01HS019356, 1R01HS022640); Vanderbilt Institute of Clinical and Translational Research (UL1TR000011 from NCATS/NIH); NIH/NCI Grant 5T32CA106183 (MDT). Research reported in this article was partially funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award CE 12-11-4667. The statements in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. Each funding organization provided financial support through grants, but none was involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Bibliography

- 1.Thompson I, Thrasher JB, Aus G, et al. Guideline for the Management of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: 2007 Update. J Urol. 2007;177(6):2106–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makarov D, Fagerlin A, Chrouser K, et al. AUA White Paper on Implementation of shared decision making into urological practice. Urol Pract. 2015;3(5):1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.urpr.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(3):203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(10):932–942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-Year Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606220. NEJMoa1606220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheets NC, Goldin GH, Meyer A, et al. Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy, Proton Therapy, or Conformal Radiation Therapy and Morbidity and Disease Control in Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1611–1620. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs BL, Zhang Y, Skolarus TA, et al. Managed care and the diffusion of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Urology. 2012;80(6):1236–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs BL, Zhang Y, Skolarus TA, Hollenbeck BK. Growth of high-cost intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer raises concerns about overuse. Health Aff. 2012;31(4):750–759. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanamadala S, Chung BI, Hernandez-Boussard TM. Robot-assisted versus open radical prostatectomy utilization in hospitals offering robotics. [Accessed September 25, 2016];Can J Urol. 2016 23(3):8279–8284. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27347621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberlin DT, Flum AS, Lai JD, Meeks JJ. The effect of minimally invasive prostatectomy on practice patterns of American urologists. Urol Oncol. 2016;34(6):255e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowrance WT, Eastham JA, Savage C, et al. Contemporary open and robotic radical prostatectomy practice patterns among urologists in the United States. J Urol. 2012;187(6):2087–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.01.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barocas DA, Chen V, Cooperberg M, et al. Using a population-based observational cohort study to address difficult comparative effectiveness research questions: the CEASAR study. J Comp Eff Res. 2013;2(4):445–460. doi: 10.2217/cer.13.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Sanda MG. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the expanded prostate cancer index composite instrument for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology. 2010;76(5):1245–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. Minimally important difference for the expanded prostate cancer index composite short form. Urology. 2015;85(1):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resnick MJ, Barocas DA, Morgans AK, et al. Contemporary prevalence of pretreatment urinary, sexual, hormonal, and bowel dysfunction: Defining the population at risk for harms of prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2014;120(8):1263–1271. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McHorney Ca, Ware JE, Raczek aE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–263. doi: 10.2307/3765819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jayadevappa R, Malkowicz SB, Wittink M, Wein AJ, Chhatre S. Comparison of distribution- and anchor-based approaches to infer changes in health-related quality of life of prostate cancer survivors. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(5):1902–1925. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan K-H, et al. Long-Term Functional Outcomes after Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(5):436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stier DM, Greenfield S, Lubeck DP, et al. Quantifying comorbidity in a disease-specific cohort: Adaptation of the total illness burden index to prostate cancer. Urology. 1999;54(3):424–429. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Recurrence After Radical Prostatectomy or External-Beam Radiation Therapy for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):168–172. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haley SM, McHorney CA, Ware JE. Evaluation of the mos SF-36 physical functioning scale (PF-10): I. Unidimensionality and reproducibility of the Rasch Item scale. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(6):671–684. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Gandek B, Rogers WH, JEW Characteristics of physicians with participatory decision making styles. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:497–504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohler J, Bahnson RR, Boston B, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer. Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2010;8(2):162–200. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, et al. Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: The Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(9):891–899. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical Prostatectomy or Watchful Waiting in Early Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(10):932–942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yaxley JW, Coughlin GD, Chambers SK, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy versus open radical retropubic prostatectomy: early outcomes from a randomised controlled phase 3 study. Lancet. 2016;6736(16):1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30592-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woo SH, Kang D, Il Ha Y-S, et al. Comprehensive analysis of sexual function outcome in prostate cancer patients after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2014;28(2):172–177. doi: 10.1089/end.2013.0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollenbeck BK, Dunn RL, Wei JT, Montie JE, Sanda MG. Determinants of long-term sexual health outcome after radical prostatectomy measured by a validated instrument. J Urol. 2003;169(4):1453–1457. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000056737.40872.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kundu SD, Roehl Ka, Eggener SE, Antenor JAV, Han M, Catalona WJ. Potency, continence and complications in 3,477 consecutive radical retropubic prostatectomies. J Urol. 2004;172(6 Pt 1):2227–2231. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000145222.94455.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zelefsky MJ, Poon BY, Eastham J, Vickers A, Pei X, Scardino PT. Longitudinal assessment of quality of life after surgery, conformal brachytherapy, and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118(1):85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ficarra V, Novara G, Ahlering TE, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting potency rates after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2012;62(3):418–430. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.046. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ficarra V, Novara G, Rosen RC, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2012;62(3):405–417. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bourke L, Boorjian SA, Briganti A, et al. Survivorship and Improving Quality of Life in Men with Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68(3):374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalaski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alemozaffar M, Regan MM, Cooperberg MR, et al. Prediction of Erectile Function Following Treatment for Prostate Cancer. Jama-Journal Am Med Assoc. 2011;306(11):1205–1214. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. JAMA. 2000;283(3):354–360. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.354. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10647798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Punnen S, Cowan JE, Chan JM, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR. Long-term health-related quality of life after primary treatment for localized prostate cancer: Results from the CaPSURE registry. Eur Urol. 2015;68(4):600–608. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Neil B, Koyama T, Alvarez J, et al. The Comparative Harms of Open and Robotic Prostatectomy in Population Based Samples. J Urol. 2016;195(2):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.08.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Neil B, Hoffman KE, Koyama T, et al. Population-Based Comparison of Patient-Reported Function After 3-Dimensional Conformal Versus Contemporary External Beam Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(2S):E399. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.06.1634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.