Abstract

Background and aim

Infertility as a global problem, affects the different aspects of women’s health. Also, violence against infertile women affects their psychological wellbeing and treatment consequence. This study aimed at reviewing related factors to violence against infertile women, based on an ecological approach.

Methods

In this systematic review, the researchers conducted their search in electronic databases such as Google Scholar, and then in more specialized ones such as Medline via PubMed, Science Direct, Up-to-date, Springer, SID, Magiran, Iranmedex and Irandoc with the key words violence, infertility, women, risk factors, social environment, and individuality, from 1988 to 2016. The selection of papers was undertaken from 20–27 January 2017. The articles were selected based on the following criteria: 1), the articles focused on the research question 2), infertility and violence were included in the title of the articles, and 3) articles were published in online journals. Exclusion criteria were articles which focused on violence against the general population, pregnant women and female sex workers and articles that were not available in full text form or written in other languages (Not Persian or English). The quality of selected studies was appraised using a 16-item checklist adapted from Tao. This checklist consisted of 16 items which used a 0 or 1 scoring system (not eligible or eligible). If an article received a score of 75% (12–16 points), it was of high quality. A score of 50% to 74% (8–12 points) indicated moderate quality, and less than 50% (8 points) indicated low quality. The process of titles, abstracts and full-texts’ appraisal led to the selection of 16 articles, which were used to write this article

Results

Two of the articles based on 16-items of the check list had high quality score, 8 of them had moderate and the remaining articles had low quality score. Our findings were classified under three categories corresponding with the ecological approach: (1) Microsystem level “individual sociodemographic and infertility characteristics”, (2) Mesosystem level “interpersonal’ and husband sociodemographic characteristics” and (3) Macro system level considered ethnicity and cultural factors.

Conclusion

Violence against infertile women and the stress caused by it, would affect the consequences of infertility treatment. It is noted that various cultural-contextual factors cause violence in different societies. There is a need for the development of screening tools and applying counselors to identify infertile women at the risk of violence, and provide clinical services, counseling and social support.

Keywords: Violence, Infertility, Women, Risk factors, Social environment, Individuality

1. Introduction

Infertility is defined as a failure in women in the reproductive age to become pregnant despite one year of unprotected sexual intercourse (1). Prevalence of infertility between countries is different, and base on international estimates of infertility, range from 6.9 to 9.3% in less-developed nations and from 3.5 to 16.7% in more developed nations (2). More than 186,000 women in developing countries are suffering from infertility (3). Furthermore, the overall prevalence of infertility in Iran was reported as 8% (4). It is shown that one of the problems that infertile women are exposed to is violence, which accrues two times more than in fertile women (5). The type of domestic violence against infertile women can vary from physical, psychological and sexual (5). The fifth aim of the Millennium Developmental Goals after 2015 has been the supplementation of gender equality and empowerment for all people (6, 7). According to the association for women’s rights through the convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (CEDAW) and conferences in Cairo (1994) and Beijing (1995), women’s empowerment requires the consideration of sexual, economic, political, judicial and fertility-related issues in every society (8, 9). Moreover, one of the seven priorities of the realization of gender equality after 2015 has been recognized to be making efforts for reducing violence against women and girls (10). Infertility causes substantial stress and leads to sudden changes in women’s relationships with family members and society (11). In many countries, the stigma of infertility leads to the rejection of people by societies and families. It also decreases the level of interaction with friends and acquaintances, gradually creates an imbalance in the marital relationship, destructs the family union and ends in divorce (12–14) In the sixth assembly of the World Health Organization (WHO) (2014), a resolution for empowering healthcare systems to fight with violence against children and women was passed (15). In 2013, the emergency department of the WHO published a report on the regional and global spread of violence, and described factors influencing women’s exposure to violence committed by men (16). Dealing with violence against infertile women and identifying influencing factors are important because along with anxiety imposed by infertility and its treatment process, violence has behavioral and psychological consequences that make the treatment of infertile women a challenge for healthcare professionals (17, 18). While previous studies have investigated the experiences of infertile women of violence (16), no study has been conducted to review the factors using the ecological approach. According to this approach, people’s living conditions vary and environmental factors affect living conditions (19). The ecological model in the social sciences defines people’s behaviors influenced by the environment, and declares that the behavior is beyond personal factors (19). These three aspects of the ecological model include the microsystem level (individual factors) that makes the conditions suitable for the occurrence of a behavior; the mesosystem level (interpersonal factors) that precipitate a type of behavior; the macrosystem level (social factors) that leads to the repetition of a behavior (20) This model has a considerable role in devising strategies for promoting health conditions in society (19). Therefore, this review study aimed to investigate prevalence and influencing factors on violence against infertile women based on the ecological approach.

2. Material and Methods

This was a systematic review, conducted based on the following steps (20):

2.1. Research design and search strategy

The research question in this study was as follows: What factors related to violence towards women with infertility? Relevant studies to answer the study question were retrieved Electronic databases and publishers such as Google Scholar, Medline via PubMed, Science Direct, Up-to-date, ProQuest, Springer, SID, Magiran, Iranmedex, and IranDoc were searched using the key words violence, infertility, women, risk factors, social environment, and individuality, from 1988 to 2016. The selection of papers was undertaken from 20–27 January 2017. Also, the reference lists of relevant articles were searched. A systematic review was conducted after development of the research question with experts’ panel ideas. This design has been found suitable for improving knowledge and collecting comprehensive data, because studies had different assessment tools and methods after searching and collecting data.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The articles were selected based on the following criteria: 1), the articles focused on the research question (what factors are related to violence against women with infertility) 2), infertility and violence were included in the title of the articles, and 3), articles were published in online journals. Exclusion criteria were articles which focused on violence against the general population, pregnant women and female sex workers, and articles that were not available in full text form or written in other languages (Not Persian or English).

2.3. Quality assessment

Quality assessment of full text studies was performed by two independent reviewers. Researchers reviewed summaries of all articles sought. The appraisal of the articles was conducted using a 16-item checklist (21, 22) with a two-point scale meeting the required criteria (score of 1) and not meeting the criteria (score of 0). If the sum of scores for a given article was 75% of the criteria (scores between 12 and 16), it would be considered of a high quality. If the article achieved 50–75% of the criteria (scores between 8 and 12), it had a moderate quality, and articles with less than 50% of the criteria (scores below 8), were considered a low-quality study and were excluded from the review (21, 23) (Table 1).

Table 1.

The list of evaluation criteria for assessing the quality of articles regarding infertile women’s violence.

| Violence assessment | A | A psychometrical questionnaire is used |

| B | A primary objective of the study is to examine the violence | |

| C | Standardized or valid self-report measurements are used to assess the violence in the infertile and/or their spouse/partners | |

| Study participants | D | A description is included of at least two socio-demographic variables (e.g., age, sex, economical status, educational status, etc.) |

| E | A description is present of at least two clinical variables (e.g., type of infertility, duration of infertility, treatment method(s), etc.) | |

| F | Inclusion and/or exclusion criteria are provided | |

| G | The study describes predictors or influencing factors by using correlation analysis, multivariate analyses or structural equation models | |

| H | Participation rates for the infertile women are described (defined as the percentage of eligible patients who gave their informed consent) and these rates exceed 70% | |

| I | Information is given about the ratio between non-responders versus responders | |

| Study design | J | The study size is consisting of at least 50 patients |

| K | The collection of data is prospectively gathered | |

| L | The design is longitudinal (more than 1 year) | |

| M | The process of data collection is described (e.g., interview or self-report, etc.) | |

| N | The follow-up period is at least 6 months | |

| O | The loss to follow-up is described and is less than < 20% | |

| Results | P | The results are compared between two groups or more (e.g., healthy population, groups with different treatment stages, different types of infertility, or treatment types) and/or results are compared with at least two points in time (e.g., pre- versus post-treatment) |

The criteria checklist was based on established criteria for systematic review reported in the literature (21)

3. Results

3.1. Description

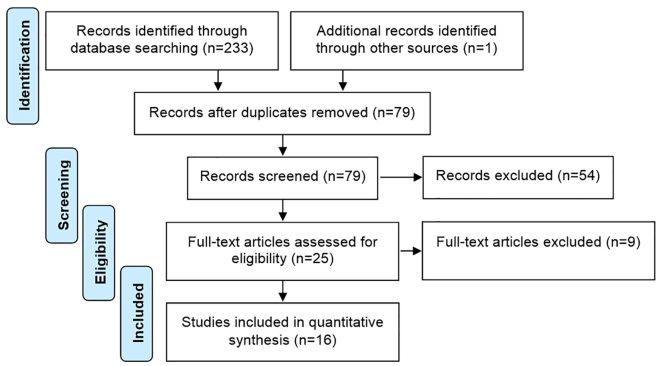

The search led to the extraction of 234 articles. After the exclusion of repeated articles, 79 articles remained. The remaining study abstracts were checked and 54 irrelevant studies were excluded. By using the full-text appraisal form, 16 articles were selected to be included in data analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process

Studies with a focus on violence against the general population, pregnant and sex workers were excluded from the review (9, 24, 25), also full text of two articles were not available (26, 27). Table 2 shows a summary of the included article selected for data analysis based on the full-text appraisal. Design of studies were cross-sectional except one review article (16) and 3 comparative ones and one brief communication (28) (Table 2). Between the articles, one of them was from Pakistan (29), one of them was from Hong Kong (28), one was from India (30), 9 articles were from Iran (5, 31–37), 2 of them from Nigeria (38, 39), 2 of them from turkey (40, 41) and one of them was a review article. Prevalence of violence against infertile women varies in different countries. Prevalence in Iran ranged from 43.7% to 61.8% (5, 33, 34), 64% in Pakistan (29), 31.2% to 35.9% in Nigeria (38, 39) and 1.8% in Hong Kong (28).

Table 2.

Characteristics and related factors of violence against women with infertility in included studies

| Ref. no. | Sampling method, setting | n | Mean age (year) | Type and distribution of infertile women | Violence scale used (questionnaire) | Prevalence of violence (%) | Significant risk factors associated with violence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Psychological | Sexual | Total | |||||||

| 29 | NM, infertility clinics (Karachi) | 400 | 15–35 | Primary & secondary | AAS | 23.1% | - | - | 278 (64%) | Husband low education, husband unemployment status, women with no live children, women with no have son |

| 36 | Convenience sampling, RHRC (Tabriz) | 200 | 31.1 | Primary | VAW | 45% | 82% | 54% | - | - |

| 5 | NM. RHRC (Tehran) | 400 | NM | Primary | CTS2 | 14% | 33.8% | 8% | 247 (61.8%) | Husband unemployment, husband less than secondary education, coercive marriage |

| 33 | Convenience sampling, infertility center (Tehran) | 400 | 30.50 | Primary & secondary | DV | 5.3% | 74.3% | 47.3% | - (34.7%) | Unwanted marriage, married younger 1, longer marriage duration 2, marriage dissatisfaction 3, number of IVFs, had microinjection 4, weak mental state 5, drug abuse,-Mental and physical, emotional status of the women, smoking and addiction, husband behavioral disorder 6, drug abuse of the spouse 7, diseases of the husband8, other ethnic of husband respect to wife(Tehran) 9 |

| 34 | NM, RHRC (Tehran) | 400 | 30.09 | Primary | CTS2 | 14% | 33.8% | - | 191 (47.8%) | Husband education lower than secondary education, coercive marriage, husband unemployment |

| 41 | Convenient, IVFC (Ankara) | 139 | 29.8 | Primary | SDVW | - | - | - | - | Infertility duration (> 6 years), infertility treatment (>3 years) |

| 38 | Consecutive sampling, gynecology obstetric clinic (Ado-Ekiti) | 170 | NM | Primary & secondary | WHO –V* | - | - | - | 53 (31.2%) | Unemployment, legality of marriage, polygamous marriage, Husbands’ smoking & alcohol habits, primary infertility, Prolonged duration of infertility(>5 years)2 |

| 35 | Random Sampling, infertility center (Urmia) | 384 | NM | Primary | Onat –VAW* (High score mean means high violence) | - | - | - | - | Age of wife & husband, primary and lower education of wife & husband, lengthening the duration of marriage, lengthening the awareness of the infertility |

| 39 | Systematic sampling, AKTH (Kano) | 373 | 28.0 | Primary (37%), | IPV | 18.7% | 94.0% | 82.8% | 134 (35.95) | Lack of formal education, employment in the informal sector, unemployed spouse, low level of education of husband or wife |

| 32 | Multistage sampling, infertility center (Tehran) | 410 | 30.50 | Secondary (63%) | IPV | - | 74.3% | - | - | Physical diseases of spouse, ethnicity of spouse, duration of marriage (>5year), duration of infertility (>48month), microinjection Attempts, frequency of IVF Attempts (>2)1, threats of divorce, neurological diseases of spouse, physical diseases of spouse, spouse addiction, age of spouse |

| 37 | Comparative-study, random sampling (Mashhad) | 200 | - | 100 (infertile) 100 (fertile) | VF | - | - | - | - | No significant relationships between sexual disorder and wife abuse against infertile women. |

| 31 | Comparative study, Infertility center (Isfahan) | 131 | 27.5 | 131 (women), 131 (men) | PASNP | - | - | - | - | Female factor (p<0.05), significant difference in the mean scores of perceived non-physical partner abuse and factor of infertility |

| 28 | Consecutive, infertility clinic (Hong Kong) | 500 | NM | - | AAS | 33.3% | 55.6% | - | 9 (1.8%) | The lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence was 1.8% (9/500) |

| 40 | convenience sampling, IVFC (Ankara) | 228 | 29.54 | 204 (fertile), 228 (infertile) | SDVW | - | - | - | - | Women’s’ educational status (41), female & unexplained infertility |

| 30 | convenience sampling, infertility centers (Andhra Pradesh) | 200 | NM | Primary & secondary | CTS2 | 8% | - | - | - | Parents-in-law (17.5%) considered their infertile daughters-in-law are inauspicious for executing religious and ceremonial rites |

| 16 | --- | --- | ---- | ----- | Review article | - | -- | --- | - | Infertility/subfertility is associated with IPV in low- and middle-income countries |

NM: Not Mentioned, AAS: Abuse Assessment Screen, RHRC: Reproductive Health Research Center, VAW: Violence Against Women (a combination of questionnaires in other studies including Abuse Assessment Screen, Abusive Behavior Inventory, Composite Abuse Scale (CAS), Measure of Wife Abuse, Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2) and Severity of Violence Against Women Scale), CTS2: Revised Conflict Tactics Scales Questionnaire, SDVW: Scale For Marital Violence Against Women, IVFC: In Vitro Fertilization Center, DV: Domestic Violence, WHO-V: 3 Semi-Structured Questionnaire on Violence Adapted from a Validated WHO Screening Tool on Violence, IPV: intimate partner violence, AKTH: Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Onat-VAW: this questionnaire specifically measures violence against infertile women that designed by Onat (2014) in turkey and also Persian validity and reliability assessed. VF: Violence in family, PASNP: Partner abuse scale Non-physical.

3.2. The studies’ quality

Quality of 16 articles was assessed based on the checklist and classification of factors influencing violence towards women with infertility. Two studies received scores of 12 to 16, indicating high quality (32, 40), Eight articles had moderate quality with scores of 8 to 12 and (5, 33–35, 37, 38, 42) were published from 2010 to 2016. Six articles had low quality with scores of less than 8. The 10 high and moderate quality articles are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Scores of Quality Assessment for Articles with Moderate and High Quality

| Ref. no. | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | 8 |

| 34 | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | 8 |

| 38 | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | 9 |

| 5 | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | 8 |

| 32 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | 12 |

| 40 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | 12 |

| 39 | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | 10 |

| 42 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | 8 |

| 35 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | 8 |

| 37 | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | -- | + | 8 |

A: A psychometrical questionnaire is used, B: a primary objective of the study is to examine the violence, C: standardized or valid self-report measurements are used to assess the violence in the infertile and/or their spouse/partners, D: a description is included of at least two socio-demographic variables (e.g., age, sex, economical status, educational status, etc.), E: a description is present of at least two clinical variables (e.g., type of infertility, duration of infertility, treatment method(s), etc.), F: inclusion and/or exclusion criteria are provided, G: the study describes predictors or influencing factors by using correlation analysis, multivariate analyses or structural equation models, H: participation rates for the infertile groups and/or their spouses/partners are described (defined as the percentage of eligible patients who gave their informed consent) and these rates exceed 70%, I: information is given about the ratio between non-responders versus responder, J: the study size is consisting of at least 50 patients, K: the collection of data is prospectively gathered, L: the design is longitudinal (more than 1 year), M: the process of data collection is described (e.g., interview or self-report, etc.), N: the follow-up period is at least 6 months, O: the loss to follow-up is described and is less than < 20, P: the results are compared between two groups or more (e.g., healthy population, groups with different treatment stages, different types of infertility, or treatment types) and/or results are compared with at least two points in time (e.g., pre- versus post-treatment).

3.3. Related Factors to violence against infertile women

To classify data, at first, the main findings of the studies were listed in a Word file. Based on the ecological model, the microsystems, mesosystems and macrosystems were identified as the names of the class title. Then, the findings of the study were repeatedly studied and after the level (Micro, Meso and Macro) of each finding were determined, they were put in the suitable classes, so that the classes had a clear border and had homogeneous interior (Similarity of factors in terms of level) and external heterogeneity (difference with other classes factors) (43). These three aspects of the ecological model include the microsystem level (individual factors) that makes the conditions suitable for the occurrence of a behavior; the mesosystem level (interpersonal factors) that precipitate a type of behavior; the macro system level (social factors) that leads to the repetition of a behavior. All factors and study characteristics are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Related Factors to Violence against Women with Infertility

| Ecological approach | Related factors in selected articles | |

|---|---|---|

| Microsystem level | Sociodemographic factors | Age, primary and lower education, Lack of formal education, employment in the informal sector, coercive or unwanted marriage, married younger, marriage dissatisfaction, Longer marriage duration, duration of marriage more than 5 years, illegality of marriage and Polygamous marriage, drug abuse of women. |

| Infertility characteristics | women with no live children, primary infertility, female or unexplained infertility, Infertility duration (> 6 years) and duration of infertility more than 5 years, Infertility treatment (≥3 years), number of IVF more than 2 and history of microinjection, women’s lengthening awareness of being infertile. | |

| Mesosystem level | Interpersonal and Husband’s characteristics | husband’s low education and husband’s unemployment status, husband’s age, physical diseases, neurological diseases of spouse, mental diseases, unemployment and criminal records, unemployment and couple’s low educational level, unofficial job, and Drug abuse of spouse like spouse’s consumption of cigarette and alcohol, husbands’ high income and behavioral disorder |

| Macro system level | Social factor | Ethnicity, culture (women with no live son child) due to gender of men considers symbol of power; Low and medium incomes of countries. |

4. Discussion

The present study focuses on factors associated with violence towards infertile women. This systematic review research aims to make the treatment team aware of what factors influence violence, since reducing violence pressure and stress can notably help treatment goals’ development. In our extracted studies, we found out a great number of differences affecting various factors in violence. Our findings imply that the demographic factors can be influencing factors, like women’s educational status; it is perceived that women with low educational levels are more in danger of violence (40). Consistent with the findings of this study, a 2015 study by Iliyasu showed the relationship between the low educational level of couples and the prevalence of domestic violence (39). A 2011 study by Etesami-pour reported that the educational level of people did not affect exposure to domestic violence (44). One of the reasons is that women with low educational level have to depend on their husband in cultures with male-centered domination and also different questionnaires were used for different studies. Low age in marriage is another related factor to violence against women with infertility (40). Consistent with the findings of this study, a 2014 study by Sheikhan reported that those women who married at younger ages, with a shorter time passed from marriage were at the risk of violence (33). Similar to our study, in the sex worker population, some factors like marriage age, having sexual infection and lower age for onset of sexual activity were a significant factor to violence against women (9). One of the reasons is that women with low-age marriage, may be unfamiliar with violence’s protective issues, and also are at risk of violence in cultures with male-centered domination. Furthermore, another factor was people’s economic status. The study by Sheikhan in 2014 showed that those people whose spouses had a job with a higher salary were more exposed to violence than those people whose spouses were unemployed (33). Contrary to results of this study, a 2011 study by Iliyasu found that spouses’ unemployment status was related to domestic violence against infertile women (39). The probable reason is diversity in different countries’ cultures and application of various data collection methods. Also, causes and duration of infertility are related factors to violence too. Those women with feminine or unknown causes of infertility are more at risk of violence (40). Consistent with this study, the study by Taebi mentioned that female infertility is a related factor to violence, the reason may be male domination in some cultures and this may also be due to some cultures believing that a woman with an unknown cause of infertility is solely responsible for infertility. When the woman was considered responsible for infertility, an important question to ask was whether there was a high risk of domestic violence against the women. This referred to the role of gender in different cultures, where those women responsible for infertility experienced gender-based violence. Also, study shows that duration of infertility for three years or more were more at risk of domestic violence (40). Consistent with this study’s findings, a 2015 study by Aduloju showed that, unemployed women with multiple marriages, primary infertility and a history of infertility for more than 5 years, reported more violence. One study showed that those people with a history of infertility for more than three years reported higher levels of anxiety and marital dissatisfaction (23). A 2016 study by Moghaddam Tabrizi showed that, the time duration passed from infertility put infertile women at the risk of domestic violence (35). This reason is related to some problems in the infertility process. High infertility duration causes some marital dissatisfaction, interpersonal problems and violence too. A 2014 study by Sheikhan showed that domestic violence against infertile women was associated with women’s unwanted marriage, spouses’ smoking and spouses’ physical and mental problems (33). Consistent with this study’s findings, more violence reports were available from infertile women whose spouses had a habit of smoking and drinking alcohol, had illegal marriages with their husbands, and their husbands were the head of the household (38). This may be a result of the phenomenon that husbands have psychological imbalance, with high risk behavior, for this reason, women are at risk of violence too. Furthermore, in families where the husbands of the infertile women had low to primary education, their husbands had a low financial status, and it had been a long time since their marriage, infertile women were exposed to more violence (35). A 2011 study by Ardabily showed that, relationships were observed between spouses’ unemployment, their low educational level and unwanted marriage and physical, emotional and sexual violence, respectively (5, 34). A 2015 study by Ozgoli showed that, the violence of sexual partners of infertile women was associated with the ethnicity and physical diseases of the infertile women’s spouses (32). Contrary to this finding, the study by Adulejo showed that no association was observed between religion or ethnicity and violence against women (38). Differences in the cultures and contexts of countries and various data collection methods used by different studies can bring different meanings of violence to mind, and lead to different results. It is believed that infertile women undergo mental pressures by people around them and may indeed experience psychological crisis when they are frequently asked about the time of childbearing (45). The reports of violence often are hidden and unsteady due to the process of following up violence cases, shame and fear of being scolded by others, and unclear consequences of prosecution., which can lead to the repetition of violence against women (30). One factor associated with domestic violence by the sexual partner of the infertile women was their husbands’ ethnicity, this may be due to violence occurring more intensively in cultures where the male gender was considered the symbol of power. In some other cultures, the judgments and opinions of other people about infertility were more important than those of the infertile couple themselves. For instance, infertile men had feelings of disappointment and failure, because infertility meant a lack of sexual power and strength. This feeling leads to losing confidence and the feeling of abandonment (32). Religious beliefs about life after death and the number of children, affected the person’s life expectancy in some cultures. The male children were more valued than daughters in some countries, and the death of a male child brought the probability of domestic violence against women. One of the consequences of infertility for a woman in such societies was the issue of stigma. The infertile woman was often deemed as a useless, ominous person who brought shame. Being abandoned by the family and spouse was a consequence of infertility in such cultures, which ignited domestic violence (45). Religious beliefs along with the behaviors of friends and acquaintances could also have a protective role. It has been observed that infertile women protected themselves against a crisis by saying sentences like “we trust in God to fix everything” (45). Also, it has been observed that the location where the victim of violence lived was a factor for being at risk for violence (45). Consistent with this finding, a systematic review reported that infertility in countries with low and medium income levels was associated with domestic violence against women (16).

5. Conclusions

Violence against infertile women and the stress caused by it, would affect the consequences of infertility treatment. It is noted that various cultural-contextual factors cause violence in different societies. Therefore, it is so important that the health provider considers these factors in the infertility treatment process. There is a need for the development of screening tools and applying counselor clients to identify infertile women at risk of violence and provide clinical services, remedial counseling and social support. The results of this article show that various factors have an essential role in exposing infertile women to violence, so paying attention to them can play an important role in continuing their treatment. The ecological approach provides us with comprehensive information about factors influencing violence against infertile women. Healthcare providers can use such information to help with the identification of those women who are the risk of violence and provide preventive care. The limitations of this research are its limited number of papers and the unavailability of some full text articles, and the use of different tools for assessing violence towards infertile women.

Acknowledgments

This study is related to a master’s thesis in the midwifery counseling field. The project was supported financially by Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. This study’s research proposal was approved and supported financially by the Student Research Committee affiliated with Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Grant number: 226- 95). The authors also appreciate Miss Maedeh Rezaei’s collaboration with this study.

Footnotes

iThenticate screening: August 31, 2017, English editing: November 10, 2017, Quality control: November 15, 2017

This article has been reviewed/commented by three experts

Conflict of Interest:

There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

Authors’ contributions:

All authors of the study contributed to the study design. The initial version of the study was developed by Maryam Hajizade-Valokolaee, and then checked by other authors. The final version was revised by Soghra Khani and lastly, approved by all the authors.

References

- 1.Macaluso M, Wright-Schnapp TJ, Chandra A, Johnson R, Satterwhite CL, Pulver A, et al. A public health focus on infertility prevention, detection, and management. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):16.e1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1506–12. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhont N, Van de Wijgert J, Coene G, Gasarabwe A, Temmerman M. ‘Mama and papa nothing’: living with infertility among an urban population in Kigali, Rwanda. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(3):623–9. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safarinejad MR. Infertility among couples in a population-based study in Iran: prevalence and associated risk factors. Int J Androl. 2008;31(3):303–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardabily HE, Moghadam ZB, Salsali M, Ramezanzadeh F, Nedjat S. Prevalence and risk factors for domestic violence against infertile women in an Iranian setting. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112(1):15–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glasier A, Gülmezoglu AM, Schmid GP, Moreno CG, Van Look PF. Sexual and reproductive health: a matter of life and death. Lancet. 2006;368(9547):1595–607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waage J, Banerji R, Campbell O, Chirwa E, Collender G, Dieltiens V, et al. The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015 Lancet and London International Development Centre Commission. Lancet. 2010;376(9745):991–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61196-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temmerman M, Khosla R, Say L. Sexual and reproductive health and rights: a global development, health, and human rights priority. Lancet. 2014;384(9941):e30–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khani S, Banaem LM, Mohammadi E, Vedadhir A, Hajizadeh E. The most Common Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs in Women Referred to Healthcare and Triangle centers of Sari-2013. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2014;23(1):41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sen G, Mukherjee A. No empowerment without rights, No rights without politics: Gender-equality, MDGs and the post-2015 development agenda. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities. 2014;15(2–3):188–202. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2014.884057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson BD, Pirritano M, Christensen U, Boivin J, Block J, Schmidt L. The longitudinal impact of partner coping in couples following 5 years of unsuccessful fertility treatments. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(7):1656–64. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araoye MO. Epidemiology of infertility: social problems of the infertile couples. West Afr J Med. 2003;22(2):190–6. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i2.27946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutstein SO, Shah IH. Infecundity infertility and childlessness in developing countries. Popline.org. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui W. Mother or nothing: the agony of infertility. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(12):881–2. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.011210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Organization WH. Governing body matters: Key issues arising out of the Sixty-eighth World Health Assembly and the 136th and 137th sessions of the WHO Executive Board-SE; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stellar C, Garcia-Moreno C, Temmerman M, Van der Poel S. A systematic review and narrative report of the relationship between infertility, subfertility, and intimate partner violence. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebbesen SM, Zachariae R, Mehlsen MY, Thomsen D, Højgaard A, Ottosen L, et al. Stressful life events are associated with a poor in-vitro fertilization (IVF) outcome: a prospective study. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(9):2173–82. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. The lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hajizade-Valokolaee M, Yazdani-Khermandichali F, Shahhosseini Z, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health: an ecological perspective. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016;29(4) doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2015-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tao P, Coates R, Maycock B. Investigating marital relationship in infertility: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Reprod Infertil. 2012;13(2):71–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezaei M, Elyasi F, Janbabai G, Moosazadeh M, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Factors Influencing Body Image in Women with Breast Cancer: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(10):e39465. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.39465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samadaee-Gelehkolaee K, Mccarthy BW, Khalilian A, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Peyvandi S, Elyasi F, et al. Factors Associated With Marital Satisfaction in Infertile Couple: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;8(5):96–109. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n5p96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hajikhani Golchin NA, Hamzehgardeshi Z, Hamzehgardeshi L, Shirzad Ahoodashti M. Sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant women exposed to domestic violence during pregnancy in an Iranian setting. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(4):e11989. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.11989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsanezhad ME, Jahromi BN, Zare N, Keramati P, Khalili A, Parsa-Nezhad M. Epidemiology and etiology of infertility in Iran, systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Womens Health, Issues and Care. 2016;2013 doi: 10.4172/2325-9795.1000121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ameh N, Kene TS, Onuh SO, Okohue JE, Umeora OU, Anozie OB. Burden of domestic violence amongst infertile women attending infertility clinics in Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2007;16(4):375–7. doi: 10.4314/njm.v16i4.37342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasi A, Hanchate M. Infertility and domestic violence: Cause, consequence and management in Indian scenario. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung TW, Ng EH, Leung WC, Ho PC. Intimate partner violence among infertile women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(3):323–4. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(03)00298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tazeen S, Sami N., Dr Domestic violence against infertile women in Karachi, Pakistan. Asian Review of Social Sciences. 2012;1(1):15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geethanjali R, Prabhakar K. NGOs Role in Domestic Violence among the Infertility Women in Prakasam District. International Journal of Social Science Tomorrow. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taebi M, Gandomani SJ, Nilforoushan P, Gholami Dehaghi A. Association between infertility factors and non-physical partner abuse in infertile couples. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research. 2016;21(4):368. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.185577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozgoli G, Sheikhan Z, Zahiroddin A, Nasiri M, Amiri S, Kholosi Badr F. Evaluation of the prevalence and contributing factors of psychological intimate partner violence in infertile women. Journal of midwifery and reproductive health. 2016;4(2):571–81. doi: 10.22038/jmrh.2016.6625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheikhan Z, Ozgoli G, Azar M, Alavimajd H. Domestic violence in Iranian infertile women. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014;28:152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moghadam Z, Ardabily H, Salsali M, Ramezanzadeh F, Nedjat S. Physical and psychological violence against infertile women. Journal of Family and Reproductive Health. 2010;4(2):65–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moghaddam Tabrizi F, Feizbakhsh N, Sheikhi N, Behroozi Lak T. Exposure of Infertile Women to Violence and Related Factors in Women Referring to Urmia Infertility Center in 2015. Journal of Urmia Nursing And Midwifery Faculty. 2016;13(10):853–62. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farzadi L, Ghasemzadeh A, Asl ZB, Mahini M, Shirdel H. Intimate Partner Violence against Infertile Women. Journal of Clinical Research & Governance. 2014;3(2):147–51. doi: 10.13183/jcrg.v3i2.168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tabrizi G, Tabrizi S, Vatankhah M. Female Infertility Resulting in Sexual Disordes and Wife Abuse. Pazhoheshnameh-Ye Zanan (Women’s Studies) 2011;1(2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aduloju PO, Olagbuji NB, Olofinbiyi AB, Awoleke JO. Prevalence and predictors of intimate partner violence among women attending infertility clinic in south-western Nigeria. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;188:66–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iliyasu Z, Galadanci HS, Abubakar S, Auwal MS, Odoh C, Salihu HM, et al. Phenotypes of intimate partner violence among women experiencing infertility in Kano, Northwest Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(1):32–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akyuz A, Seven M, Şahiner G, Bakır B. Studying the effect of infertility on marital violence in turkish women. Int J Fertil Steril. 2013;6(4):286–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akyüz A, Şahiner G, Seven M, Bakır B. The effect of marital violence on infertility distress among a sample of Turkish women. Int J Fertil Steril. 2014;8(1):67–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yildizhan R, Adali E, Kolusari A, Kurdoglu M, Yildizhan B, Sahin G. Domestic violence against infertile women in a Turkish setting. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104(2):110–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative contenr analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to acheive trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Etesami Pour R, Banihashemian K. Comparison of sex disorders and couple abuse among fertile and infertile women. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2011;18(1):10–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ofovwe C, Agbontaen-Eghafona K. Infertility in Nigeria: A risk factor for gender based violence. Gender & Behaviour. 2009;7(2):2326. doi: 10.4314/gab.v7i2.48687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]