Abstract

The recent environmental tragedy in Flint, Michigan, where lead-contaminated drinking water raised fears of potential health effects for exposed children, revealed the failure of a regulatory system to protect residents from lead exposure. Flint is clearly not alone as a community of color where residents are disproportionately exposed to lead from paint, dust, soil, or water. In southeast Los Angeles County, California, a facility that recycled lead-acid batteries has polluted the air and soil of communities nearby for decades. Termed as “environmental disaster” by the governor, this large-scale pollution of the air and soil in largely Latino communities is emblematic of the continued risk associated with facilities that make or recycle lead-acid batteries. We discuss the influence of industrial lead emissions on public health, the roles of agencies charged with prevention of lead exposure in California, and the fractured system that allowed this large-scale contamination to persist for decades. Finally, we offer recommendations on how public agencies can improve public health surveillance of lead exposures and step out of their individual “silos” to share information and collaborate to better protect vulnerable children, workers, and communities.

Keywords: : lead, smelters, government agencies, Exide, public health

Introduction

Inorganic lead is a potent neurotoxin that can cause damage to almost all organs. While acute lead poisonings are now rare in the United States, exposures remain widespread.1 Even at low levels, lead can cause cognitive deficits, neurodevelopmental delays, and psychological impairments.2 The annual economic toll from lead exposure in California alone is estimated to result in lost earnings of $8–$11 billion dollars over the lifetime of children.3 Compelling scientific evidence concludes that there is no “safe” threshold of childhood lead exposure.4,5 Particularly vulnerable are children in communities with older housing stock, increasing the risk of lead in paint or plumbing, and in communities near industrial lead sources.6,7

The United States is the second leading producer of recycled lead, after China, producing about 19% of the world's supply in 2012, with the metal reclaimed primarily from lead-acid batteries.8 Although large numbers of spent batteries are now sent overseas, the tonnage of lead-acid batteries recycled in the United States has more than doubled in the last 40 years, while the industry has rapidly consolidated production into a handful of communities.9 To reclaim lead for use in new batteries, the old batteries are cracked, washed, pulverized and melted in a furnace at facilities known as smelters. During the process, some lead is released into the surrounding environment. Lead does not degrade, may persist indefinitely in soil, and is frequently detected in dangerous concentrations in both soil and ambient air near smelters that remove lead from mined ore10 or from recycled batteries.11

Lead production has long been associated with community harm and adverse health effects of workers. Historical records as early as the 1890s show farmers complaining about dust emissions, contamination of streams, and harm to livestock from smelters that removed lead from ore.12 As early as the 1970s, research demonstrated extremely high rates of childhood lead poisoning among those living near and working in U.S. lead smelters.13,14,15

Lead exposure in children is preventable. Primary prevention of lead poisoning requires reducing exposure through the identification and control of lead sources in air, water, dust, soil, and paint—before exposure occurs. Regulations regarding manufacturing, use, environmental emissions, and disposal of lead have been implemented over the past five decades.16 As the use of lead in various products (paint, gasoline, pipes, etc.) has been phased out, lead levels in ambient air, water, and soil have also decreased. As a result, the country has seen marked declines in blood lead levels (BLLs) over the past four decades.17 While policies have aimed at removing sources of lead, lead continues to be used in the manufacture of automotive batteries for cars, buses, trucks, tractors, and motorcycles.

Today, however, public health agencies by and large focus on secondary prevention, that is, investigating causes of elevated blood lead levels (EBLLs) only after individuals have suffered exposure.18 This leaves major gaps in the U.S. public health system for lead exposure prevention, particularly with respect to low-income and communities of color. The resulting failures in primary prevention rose to national spotlight in the Flint tragedy,19 but similar gaps have recently been revealed in a very different context in southern California. For more than 30 years, a lead-acid battery smelter, Exide Technologies operated in southeastern Los Angeles County on temporary state permits, in violation of multiple federal environmental regulations, exposing residents to toxic metals.

Discussion

A disaster in the making: lead smelting and regulatory agencies

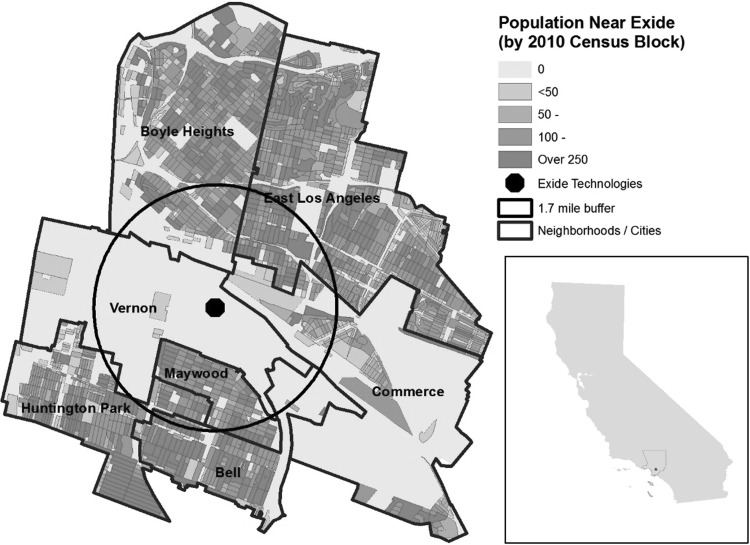

The Exide facility is located on a site that was used for metal recovery operations for nearly a century and for battery recycling since the late 1970s, with a capacity to process 120,000 tons of lead per year, ∼11 million batteries.20 The 24-acre site is in the city of Vernon, about 7 miles southeast of downtown Los Angeles (Fig. 1). Vernon calls itself “exclusively-industrial” and has fewer than 120 residents. Battery recycling facilities such as Exide are regulated by multiple overlapping state and federal agencies. A state agency, the Department of Toxic Substances (DTSC), regulates the hazardous waste from the facility, including potential soil contamination; a regional agency (the South Coast Air Quality Management District, AQMD) regulates air emissions from point sources; and a county agency (Los Angeles County Department of Public Health or “County Health”) evaluates cases of lead poisoning.

FIG. 1.

Neighborhoods and population surrounding Exide Technologies. Boyle Heights is in the City of Los Angeles. Circle shows the 1.7-mile radius. Prevailing wind direction is northeast.

For decades DTSC allowed the Exide facility to operate under interim status authorization rather than the full permit required by federal law. DTSC was the first agency that identified and cited violations at Exide in 1987, detecting lead and other toxic metals in unpermitted waste piles, and in 1999, the agency found elevated levels of lead in soil. Nonetheless, a 2006 DTSC report claimed that both emissions and impacts of the facility “were determined to be less than significant.”21 Just 2 years later, a DTSC investigation of nearby soil found lead concentrations up to 52,000 ppm (with concentrations ≥1000 ppm considered hazardous waste in California).22 None of these findings prompted investigations into potential exposures in residents.

AQMD has collected ambient air samples near facilities that use or process lead since 1991. In 2007—after residents complained about dust and ash fallout on their properties, AQMD began a focused investigation of Exide.23 The next year, AQMD monitors repeatedly recorded 30-day averages in excess of 2.5 μg/m3, 66% above the federal air quality standard at the time. The standard has since been lowered to 0.15 μg/m3.24 The agency ordered Exide to recycle fewer batteries and determined that “AQMD has taken necessary steps to ensure that Exide's emissions will not pose a threat to public health.”25 To our knowledge, these exceedances did not trigger any investigation into the exposures in the community or for the workers.

After years of public concern, an AQMD Health Risk Assessment (released March 2013) concluded that as many as 250,000 residents face a chronic health hazard from exposure to lead and arsenic emitted from the stacks of the smelter and settling onto residential soil. Not only did this report validate community concerns but also it renewed community organizing efforts targeting the air and soil pollution from Exide and the neglect from regulators. Subsequently, various regulatory agencies claimed that they could enforce safe operations at Exide, but there were dozens of investigative news reports, community protests and public meetings that countered this narrative. Finally, in May 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice intervened and entered a Non-Prosecution Agreement with Exide Technologies “to immediately and forever close a battery recycling facility in Vernon and to pay $50 million to clean up the site and surrounding neighborhoods, which have been affected by environmental toxins for close to a century” in lieu of criminal prosecution. Exide admitted to four felonies: the illegal disposal, storage, shipment, and transportation of hazardous waste.26

However, this did not address lead contamination in the soil because of the facility's historical operations. For months, community leaders, including from environmental justice organizations, in partnership with public officials and academics (including the authors), met as part of a formal appointed advisory committee with governing bodies to work out details, with DTSC finally conceding that the reach of Exide's pollution could extend at least 1.7 miles from the facility. Twenty-four years after the AQMD began monitoring the battery recycler and 30 years since the first violation recorded by DTSC, California's Governor declared Exide an “environmental disaster” and allocated $176 million of public funds for investigation and remediation. In 2016, data suggested that 99% of properties within 1.7 miles of the facility sampled have soil lead levels that exceed the California residential soil standard of 80 ppm, which was established to avoid BLLs above 1 μg/dL and intelligence quotient (IQ) losses exceeding one point. Using available data from DTSC, an estimated 25% of homes within 1.7 miles have at least some soil lead sample that exceeded hazardous waste limits of 1000 ppm. Furthermore, a State Health analysis concluded that children living near Exide had BLLs twice as high as the average in children county-wide.27

Agencies in silos

Multiple California agencies are tasked with preventing lead exposure of residents and workers, yet for decades, the situation at Exide and its widespread impact went uncorrected (Table 1). The events unfolding around Exide (as well as in other communities) suggest the need to systemically improve the public health surveillance and prevention of lead exposure in both children and workers, especially via soil, water, and dust. Despite all the data available from routine environmental and public health data, the various agencies operated in their own silos, failing to come together to act on the public health threat that Exide posed.

Table 1.

Agencies in California with Regulatory Authority Involving Exide

| Public Agency | Role in lead poisoning prevention | Authority |

|---|---|---|

| DTSC | Tasked with enforcing hazardous waste laws, reducing hazardous waste generation, restoring contaminated resources, and encouraging the manufacture of chemically safer products. Lead agency for the Exide remediation. | Regulates companies that handle hazardous waste under the authority of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976. |

| CDPH CLPPP and OLPPP (State Health) | Mission to reduce exposure of children and adult workers to lead. | Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Acts of 1986 and 1989 established the CLPPP within the CDPH. In addition, the California Health and Safety Code mandates medical laboratories to report cases of children with EBLLs to the California Department of Health Services. Since passage of SB 460 medical laboratories are required to report all blood lead levels, California Health and Safety Code Sections 105185–105195 established the OLPPP. |

| Cal/OSHA | Responsible for overseeing worker health and safety on the job. | Establishes permissible exposure limits, medical surveillance, special protective measures, and exposure monitoring. |

| South Coast AQMD | Regulation of air emissions from all facilities that use or process lead containing materials. Enforces federal and regional air quality standards. | Regulates air emissions under the Title V permit program. |

| Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (County Health) | Investigates cases of EBLLs in children. | Under contract to the CDPH. |

AQMD, Air Quality Management Distance; Cal/OSHA, California Division of Occupational Safety and Health; CDPH, California Department of Public Health; CLPPP, Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program; DTSC, Department of Toxics Substances Control; OLPPP, Occupational Lead Poisoning Prevention Program.

In fact, during 2013–2016, the agencies charged with protecting the public and workers against lead exposure openly refused to work together to mitigate the hazards or to share information with the public. Some examples:

• At a public hearing in 2013, AQMD officials stated that they did not want to cooperate with DTSC on Exide lead contamination issues.

• Until 2016, the California Department of Public Health's Occupational Lead Poisoning Prevention Program (OLPPP) would not disclose the names of Exide employees with EBLLs to County Health, arguing that it was State Health's mandate to investigate worker safety, not the County's.

• The California Department of Public Health's Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program (CLPPP) did not release annual reports on surveillance or provide publicly accessible updated information on BLLs.

• The CDPH OLPPP and CLPPP Branches have databases of EBLLs in children and workers, but the databases do not readily communicate, thwarting attempts to detect “take-home” lead exposure of children via their parents or others in the household.

• DTSC has yet to provide maps to the public showing where the agency has detected soil contamination.

The United States has an extensive lead biomonitoring program, with requirements and recommendations for children to be screened in certain circumstances. More data exist on personal childhood lead exposures in this country than on almost any other environmental toxicant. Yet, in 2017, the potential aggregate lead exposure of the nearby communities due to operations at Exide is still unknown due to inadequate surveillance and analysis of the existing data.

Children

The CLPPP receives all blood lead results for minors in the state. It may therefore be expected that a pattern of elevated lead exposure could be identified through such biomonitoring. However, the extent of childhood testing is limited. While California mandates that all children on public programs (e.g., WIC, Medical) receive a free blood lead test at ages 1 and 2, a previous analysis suggested that as of 1999 fewer than 25% of children enrolled in Medical received blood lead tests and many children are not receiving the necessary services.28,29 As a result of undertesting of children, it is estimated that the state identifies only 37% of children with BLLs ≥10 μg/dL.30

There is little evidence that the State's childhood lead database has been used for the planning or evaluation of prevention of lead exposure. Rather, it is narrowly focused on limited investigation of individual cases and addressing sources of exposure only after poisoning has occurred. The result is a “case management” approach to lead-poisoned children, currently defined in Los Angeles County as one BLL test ≥20 μg/dL (or two BLLs ≥15 μg/dL at least 3 months apart). In these cases, children receive home visits to try to identify the sources of the lead. However, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended using a “reference level” of 5 μg/dL in 2012, and some states have adapted more protective intervention protocols; however, as of March 2017, Los Angeles County Health's threshold for intervention was essentially quadruple the CDC guidelines.

Although all blood lead test results collected in California are sent to State Health, there are several intrinsic limitations to the use of the data. First, other agencies, researchers or health professionals are not allowed to access deidentified or census block-level information to conduct the analyses that might have detected elevated lead levels near Exide. Second, the laboratories measuring BLLs routinely do not report any data to State Health if the levels are <5 μg/dL—despite readily available technology to measure levels at ±1 μg/dL.31 Therefore, a large amount of data regarding trends in children with levels of blood lead <5 μg/dL is lost, despite significant evidence of harm at low exposure levels.

Workers

Occupational take home exposure from workers in lead industries can cause high BLLs for their children.29 In recent years, among tested workers, the OLPPP has identified 15% as having EBLLs, the majority working in the manufacturing sector.32 State Health informed the authors that it had seen EBLLs among Exide workers, although this information was not shared with California Division of Occupational Safety and Health. Had State Health notified other agencies about Exide workers' EBLLs before 2016, it may have prompted earlier investigations to determine if children and other community members were being adversely affected by “take home” exposures of lead dust. In 2016, County Health, only after requesting the data from State Health, identified two children of former Exide workers as having EBLLs.

Conclusions

Preventing lead exposure in the twenty-first century

There are well-documented disparities in lead poisoning across racial and socioeconomic status that persist today.33 Communities living near Exide are more than 90% Latino and that rank among the top 10% of most environmentally burdened areas of the State, according to CalEnviroScreen2.0. As removal of lead-contaminated soil has begun in some residential properties, most families continue to live in their homes while this occurs. These events unfolding around Exide (and in Flint, MI and other communities) suggest the need to systemically improve the public health surveillance for lead exposure for both children and workers, especially for soil, water, and dust pathways. They also show the need for investigating government responses to environmental crises in low-income communities of color.

Lead is still widely used; in Southern California alone 100 regulated facilities emit more than 2600 pounds of lead annually, according to AQMD. The Exide disaster highlights the silos in which public agencies operate and the adverse impacts these silos have on community health, particularly among marginalized and vulnerable residents. It further provides impetus to reform and improve lead poisoning prevention.

We offer the following recommendations relevant to California and beyond:

Environmental and Air Quality Agencies (e.g., DTSC, AQMD)

• Compile information from multiple agencies regarding industrial users of lead, to inform the targeted assessment and analysis of BLLs annually. Make this information publicly available.

• Have regional air pollution agencies share information about emission violations with health departments, with state hazardous waste programs, with state and/or federal worker safety and health enforcement agencies, and with federal Environmental Protection Agency.

• Encourage cooperation and data sharing among federal, state, and local regulatory agencies tasked with addressing lead exposure.

Health Departments (e.g., CDPH CLPPP and OLPPP Branches)

• Share timely information about BLLs in workers with state or federal OSHA programs to ensure that exposures are reduced, particularly, if voluntary state health department efforts with employers are not reducing lead exposure.

• Notify county health departments about any employers who repeatedly have workers with EBLLs so that the county health departments are aware of potential “hot spots” and potential take-home exposures.

• Produce an annual report on childhood lead poisoning incidence in California (BLLs ≥5 μg/dL), including information on the testing rate, the number of cases reported to the state and the number of cases managed by state or local health departments.

• Analyze the spatial distributions of BLLs in communities by census tract and investigate “hot spots” via active surveillance.

• Update State Health and County Health databases of EBLLs so that addresses of workers and children can be readily compared to detect cases of potential childhood lead poisoning, resulting from take-home exposures.

Exposure to lead is a longstanding public health issue—and despite the decades of attention this one toxin has received—there remains a fractured system for preventing lead exposure. There is an urgent need for agencies to proactively cooperate and share information to prevent lead exposure across all communities in the United States. For 30 years, Exide exposed tens of thousands of residents to lead emissions, and yet, agencies largely ignored the public health implications. As lead production and use is concentrated in communities already burdened by environmental contamination, it is important to improve proactive surveillance and eliminate lead poisoning.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grant No. 5P30ES007048). We also recognize the director of one of the key involved groups and cochair of the committee, mark! Lopez of East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice, in 2017 was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for North America for his efforts to shut down Exide and clean up its pollution.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Robert L. Jones, David M. Homa, Pamela A. Meyer, Debra J. Brody, Kathleen L. Caldwell, James L. Pirkle, et al. “Trends in Blood Lead Levels and Blood Lead Testing Among US Children Aged 1 to 5 Years, 1988–2004.” Pediatrics 123 (2009): e376–e385.

Ronnie Levin, Mary Jean Brown, Michael E. Kashtock, David E. Jacobs, Elizabeth A. Whelan, Joanne Rodman, et al. “Lead Exposures in U.S. Children, 2008: Implications for Prevention.” Environmental Health Perspectives 116 (2008): 1285–1293.

California Environmental Health Tracking Program, Costs of Environmental Health Conditions in California Children, 2015.

Bruce P. Lanphear, Richard Hornung, Jane Khoury, Kimberly Yolton, Peter Baghurst, David C. Bellinger, et al. “Low-Level Environmental Lead Exposure and Children's Intellectual Function: An International Pooled Analysis.” Environmental Health Perspectives 113 (2005): 894–899.

Phillipe Grandjean and Philip J. Landrigan. “Developmental Neurotoxicity of Industrial Chemicals.” Lancet (London, England) 368 (2006): 2167–2178.

Shilu Tong, Yasmin E. von Schirnding, and Tippawan Prapamontol. “Environmental Lead Exposure: A Public Health Problem of Global Dimensions.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78 (2000): 1068–1077.

Ronnie Levin, Op. cit.

William P. Eckel, Michael B. Rabinowitz, and Gregory D. Foster. “Discovering Unrecognized Lead-Smelting Sites by Historical Methods.” American Journal of Public Health 91 (2001): 625–627.

William P. Eckel, Michael B. Rabinowitz, and Gregory D. Foster. Ibid.

Marianne Sullivan. “Reducing Lead in Air and Preventing Childhood Exposure Near Lead Smelters: Learning from the U.S. Experience.” New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy 25 (2015): 78–101.

Jung-Der Wang, Wei-Tseun Soong, Kun-Tu Chao, Yaw-Huei Hwang, Chang-Sheng Jang. “Occupational and Environmental Lead Poisoning: Case Study of a Battery Recycling Smelter in Taiwan.” The Journal of Toxicological Sciences 23 (1998): 241–245.

Marianne Sullivan. Op. cit.

Dale L. Morse. “El Paso Revisited.” JAMA 242 (1979): 739–741.

Philip J. Landrigan and Edward L. Baker. “Exposure of Children to Heavy Metals from Smelters: Epidemiology and Toxic Consequences.” Environmental Research 25 (1981): 204–224.

David A. Winegar, Barry S. Levy, John S. Andrews, Philip J. Landrigan, William H. Scruton, and Michael J. Krause. “Chronic Occupational Exposure to Lead: An Evaluation of the Health of Smelter Workers.” Journal of Occupational Medicine: Official Publication of the Industrial Medical Association 19 (1977): 603–606.

Ellen K. Silbergeld. “Preventing Lead Poisoning in Children.” Annual Review of Public Health 18 (1997): 187–210.

Bruce P. Lanphear, Jennifer A. Lowry, Samantha Ahdoot, Carl R. Baum, Aaron S. Bernstein, Aparna Bole, et al. “Prevention of Childhood Lead Toxicity.” Pediatrics 138 (2016): e20161493.

Bruce P. Lanphear. “The Paradox of Lead Poisoning Prevention.” Science 281 (1998): 1617–1618.

Mona Hanna-Attisha, Jenny LaChance, Richard C. Sadler, and Allison Champney Schnepp. “Elevated Blood Lead Levels in Children Associated With the Flint Drinking Water Crisis: A Spatial Analysis of Risk and Public Health Response.” American Journal of Public Health 106 (2016): 283–290.

Department of Toxic Substances Control, Exide Technologies—Fact Sheet: Draft Permit and Draft Environmental Impact Report. <https://dtsc.ca.gov/HazardousWaste/Projects/upload/Exide_FS_dPermit.pdf>. (Last accessed on January 6, 2017).

Department of Toxic Substances Control, Exide Technologies Environmental Impact Report, Executive Summary, 2006.

Department of Toxic Substances Control, Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Corrective Action Consent Order Docket Number: P3–01/02-010, Section 5.4 Determination of Threat to Public Health, 2008.

Exide Technologies, Taking Charge: Annual Report, 2008.

South Coast Air Quality Management District, Lead Monitoring at Exide Technologies, 2014.

South Coast Air Quality Management District, Exide Ordered to Reduce Emissions, 2008.

U.S. Attorney's Office, Exide Technologies Admits Role in Major Hazardous Waste Case and Agrees to Permanently Close Battery Recycling Facility in Vernon.

Department of Toxic Substances Control, New Analysis Examines Blood Lead Levels Near Exide, 2016.

California State Auditor, Health Services: Has Made Little Progress in Protecting California's Children From Lead Poisoning, 1999.

California State Auditor, Department of Health Services: And Additional Improvements are Needed to Ensure Children are Adequately Protected from Lead Poisoning, 2001.

Eric M. Roberts, Daniel Madrigal, Jhaqueline Valle, Galatea King, and Linda Kite. “Assessing Child Lead Poisoning Case Ascertainment in the US, 1999–2010.” Pediatrics 139 (2017): e20164266.

Bruce P. Lanphear, et al. Op. cit.

Susan Payne, Rebecca Jackson, and Barbara Materna. Blood Lead Levels in California Workers 2012–2014. (California Department of Public Health, 2016).

Robert L. Jones et al. Op. cit.