Abstract

Objectives

Although social science research has examined police and law enforcement-perpetrated discrimination against Black men using policing statistics and implicit bias studies, there is little quantitative evidence detailing this phenomenon from the perspective of Black men. Consequently, there is a dearth of research detailing how Black men’s perspectives on police and law enforcement-related stress predict negative physiological and psychological health outcomes. This study addresses these gaps with the qualitative development and quantitative test of the Police and Law Enforcement (PLE) scale.

Methods

In Study 1, we employed thematic analysis on transcripts of individual qualitative interviews with 90 Black men to assess key themes and concepts and develop quantitative items. In Study 2, we used 2 focus groups comprised of 5 Black men each (n=10), intensive cognitive interviewing with a separate sample of Black men (n=15), and piloting with another sample of Black men (n=13) to assess the ecological validity of the quantitative items. For study 3, we analyzed data from a sample of 633 Black men between the ages of 18 and 65 to test the factor structure of the PLE, as we all as its concurrent validity and convergent/discriminant validity.

Results

Qualitative analyses and confirmatory factor analyses suggested that a 5-item, 1-factor measure appropriately represented respondents’ experiences of police/law enforcement discrimination. As hypothesized, the PLE was positively associated with measures of racial discrimination and depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Preliminary evidence suggests that the PLE is a reliable and valid measure of Black men’s experiences of discrimination with police/law enforcement.

Keywords: Black men, Racial profiling, Racial discrimination, Racial microaggressions, Police, Law enforcement

Over the years 2014-2016, racial profiling and racial discrimination by law enforcement agencies have come into sharp focus in the public consciousness of people in the United States. The issue has been thrust into media headlines following several high profile killings of unarmed Black men and adolescent boys at the hands of police officers. Some notable examples include Eric Garner, a 43 year-old man choked to death by an NYPD officer in 2014; Michael Brown, an 18-year-old boy shot to death by a police officer in Ferguson, MO in 2014; Walter Scott, a 50-year-old man shot eight times in the back and killed while running away from a police officer during a traffic stop in North Charleston, SC in 2015; Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old man who died from spinal injuries after being chased and detained by police, although he did not commit an offense, in Baltimore, MD in 2015; Philando Castile, a 32-year-old man who was shot to death in his car by a police officer during a traffic stop in suburban St. Paul, MN in 2016; and Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old man who was shot and killed while restrained by two officers in Baton Rouge, LA in 20161. For many in the U.S., these instances have illustrated a reality that has existed from the founding of the nation (see Blackmon, 2009; Foner, 2015) until today (see Glaser, 2014): Black men are more likely than any other group in the U.S. to be profiled, targeted, accused, investigated, wrongfully committed, harshly sentenced, and incarcerated for crimes (Carson, 2014; Harrison & Beck, 2006; Pettit & Western, 2004; Pew Center on the States, 2008). This phenomenon has been particularly salient in comments from Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey and former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder in which they cited implicit racial biases and deliberate targeting of Black men, respectively, as reasons for the overrepresentation of Black men in national crime statistics (Reilly, 2015; Reilly & Stewart, 2015).

In response to each new tragedy, there have been resounding calls-to-action from the families of the victims (e.g., Diallo & Wolff, 2004) as well as community-based (e.g., Ferguson Action, 2014), popular cultural (e.g., Cole, 2014), editorial (e.g., (Feagin, 2014), scientific (e.g., (Mays, Johnson, Coles, Gellene, & Cochran, 2013), legislative (e.g., US Congress, 2013), and judicial (e.g., American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU], 2009) sources, rallying individuals and institutions to investigate and rectify racial targeting and discrimination in law enforcement. The discipline of psychology has played an important role in answering these calls with research evincing biases expressed by police officers (e.g., Eberhardt, Goff, Purdie, & Davies, 2004; Goff, Jackson, Di Leone, Culotta, & DiTomasso, 2014).

This empirical evidence notwithstanding, there remains an important gap in the psychological literature on police-perpetrated discrimination: research investigating the effects of these experiences from the perspective of the Black men who experience them. While items related to interactions with law enforcement institutions are included in several racial discrimination scales (e.g., “Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire- Community Version”, Brondolo et al., 2005; “Experiences of Discrimination” scale, Krieger, Smith, Naishadham, Hartman, & Barbeau, 2005; “Schedule of Racist Events”, Landrine & Klonoff, 1996; “Index of Race-Related Stress” Utsey & Ponterotto, 1996), we are not aware of any psychometric instruments that specifically focus on assessing Black men’s experiences with law enforcement discrimination. This is a critical void in light of an abundant empirical literature on general stress (e.g., Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and race-related stress (e.g., Williams & Mohammed, 2013) that documents how individuals’ perspectives on stressful experiences predict negative physiological and psychological health outcomes. In order to fill a fundamental gap in the psychological literature and to provide a foundation on which social scientists and policy makers can examine and understand the psychological impact of police and law enforcement-perpetrated discrimination, we developed and validated the Police and Law Enforcement (PLE) scale.

The scientific literature investigating racial discrimination by police officers has primarily investigated crime statistics (e.g., differences in arrest rates by race/ethnicity, age and sex) and the psychological processes that undergird the phenomenon from the police officer’s perspective. For example, criminological and sociological research has documented that Black men are disproportionately more likely than men from other racial/ethnic groups to encounter police officer contact (Brunson & Miller, 2006a; Brunson & Miller, 2006b; Farrell, McDevitt, Bailey, Andresen, & Pierce, 2004; Gabbidon, 2003; Gabbidon, Higgins, & Potter, 2011; Gelman, Fagan, & Kiss, 2007; Hurst, Frank, & Lee Browning, 2000), to be arrested (Hartney & Vuong, 2009; Kochel, Wilson, & Mastrofski, 2011), and to be imprisoned (Crutchfield, Fernandes, & Martinez, 2010; Mauer, 2011; Pew Center on the States, 2008). In addition, the psychological literature has found that police officers are more likely to show automatic biases against Black men and adolescents than their peers from other racial/ethnic groups (Correll et al., 2007; Eberhardt et al., 2004), including in paradigms simulating the decision to shoot a White or Black suspect (Plant & Peruche, 2005). Recent studies have also found that officers are prone to implicitly dehumanize Black men and boys, perceiving them as more dangerous and ape-like than men and boys from other racial groups (e.g., Goff, Eberhardt, Williams, & Jackson, 2008; Goff et al., 2014). These biases likely affect the outcomes documented in studies investigating Black men’s reports of biased treatment from police such as the “Driving While Black” phenomenon (e.g., Lundman & Kaufman, 2003). While this quantitative data provides evidence for police-perpetrated discrimination from the perspective of policing statistics, police bias, and, in some cases, the victim, a valid and reliable quantitative psychometric instrument that assesses multiple forms of experienced police-perpetrated discrimination from the perspective of Black men does not exist.

In addition to the quantitative literature, qualitative studies provide a rich picture of the experience of police discrimination through the eyes of Black men, documenting their experiences associated with racial profiling and victimization (Bell, Hopson, Craig, & Robinson, 2014; Dowler & Sparks, 2008; Muller & Schrage, 2014; Weitzer & Tuch, 2005). In particular, recent qualitative evidence suggests that Black men report anger, negativity, and depressive symptoms linked to their negative experiences with police, law enforcement, and incarceration (Kendrick, Anderson, & Moore, 2007; Perkins, Kelly, & Lasiter, 2014; Rich & Grey, 2005). These studies are powerful because, as with qualitative methods more generally, they provide a nuanced, in-depth understanding of lived police-related experiences of Black men. Given the lack of quantitative studies assessing the psychosocial effects of police-perpetrated discrimination from the target’s perspective and the utility of qualitative methods in understanding the nuance of phenomena, we used a mixed-methods approach to develop a quantitative measure.

This study is informed by several theoretical frameworks that model the effects of discrimination associated with race and/or social identity and emphasize the importance of understanding discrimination from the perspectives of the people who experience it. Drawing upon the biopsychosocial model of racism as a stressor (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999), the development of the present measure focuses on the importance of individual appraisal of discrimination, referred to as perceived discrimination, and its impact on Black men’s wellbeing. This focus on individual experiences of discrimination broadens the conceptualization of racism to include stimuli (i.e., institutions, actions, images, and beliefs) that are seen as discriminatory by the individual being victimized, rather than what is deemed as discriminatory from other perspectives (e.g., Harrell, 2000; Spencer, Dupree, & Hartmann, 1997; Sue et al., 2007). Moreover, the development of the present scale is also in line with critical race theory (e.g., Delgado & Stefancic, 2012), particularly in its views of the ordinariness of racism, the social construction of race and the existence of differential racialization—particularly regarding law and law enforcement institutions.

We also build upon the empirical data that evinces the short and long-term negative psychological impact of self-reported racial discrimination for Black men (e.g., Brown et al., 2000; English, Lambert, Evans, & Zonderman, 2014; Klonoff, Landrine, & Ullman, 1999; Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Krieger, Kosheleva, Waterman, Chen, & Koenen, 2011; Mays, Cochran, & Barnes, 2007; Pieterse & Carter, 2007; Thompson, 2002; Utsey, Payne, Jackson, & Jones, 2002; Watkins, Hudson, Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2011; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). As an extension of this past research, we conducted exploratory sequential mixed methods research (Creswell, Klassen, Plano Clark, & Smith, 2011) to develop the PLE, a self-report instrument that assesses the frequency of police-perpetrated discrimination from the perspective of Black men. As such, we conducted two studies in which we collected and analyzed qualitative and pilot data and a final quantitative study built upon the findings of the qualitative results.

In Study 1, the qualitative interview and thematic analysis phase, we conducted individual interviews with 90 Black men to assess key themes and concepts. In Study 2, the measurement development and validation phase, we used 2 focus groups comprised of 5 Black men each (n=10), and intensive cognitive interviewing with a separate sample of Black men (n=15), and piloting with another sample of Black men (n=13) to assess the ecological validity of the form and content of the quantitative items. For study 3, the reliability and initial validity testing phase, we analyzed data from a probability sample of 633 Black men. As part of the quantitative validation study, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the factor structure of the measure, and structural equation models (SEM) to test concurrent and convergent/discriminant validity. In terms of the factorial structure, we hypothesized that a single factor model will fit the data well. Furthermore, we tested measurement invariance across incarceration history to assess the scale’s consistency and applicability across groups of Black men who have differential experience with the criminal justice system. We expected that the patterns of PLE experiences would stay consistent across incarceration history, such that the factor structure and factor loadings of the measure would not vary between people who have and have not been incarcerated. To test concurrent validity, we hypothesized that PLE experiences would be positively associated with depressive symptoms. With regards to convergent/discriminant validity, we tested the association between the PLE and racial discrimination scores. We expected a positive, but not complete, correlation between the scores, as this would indicate that the PLE is measuring a construct that is related to racial discrimination, but conceptually unique.

Study 1: Exploratory Qualitative Interviews

Method

Participants

Participants were 90 Black men in Atlanta, GA (n=29), Columbus, GA (n=30), and Valdosta, GA (n=31) originally recruited within the community (e.g., barbershops) using community-based advertising (e.g., flyers, postcards, word-of-mouth) as a part of the larger mixed methods Project Adofo study. The main objective of Project Adofo was to examine the socio-cultural experiences of a representative sample of Black men in the Southern U.S. and assess how masculinity, depression, stress and coping, influence sexual risk and HIV testing behaviors. Eligible participants were male, fluent in English, between the ages of 18 and 65, were current residents in one of three metropolitan areas of Georgia (Atlanta, Columbus, Valdosta), reported being HIV-negative or of unknown status, and self-identified as Black. The 18-65 age limit reflected the age range in which the majority of HIV infections among Black men occur (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Demographic information on these participants can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Black men participating in Study 1(N =90, Qualitative Study), Study 2 (N= 22, Pilot Study), Study 3(N = 1264, Quantitative Validation)

| Demographic Characteristic | Study 1 n(%) | Study 2 n(%) | Study 3 n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | M=36.7, SD=14.5 | M=35.9, SD=11.7 | M =44.2, SD=14.8 |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| Some high school or less | 14 (16) | 3 (14) | 144 (11) |

| HS graduate or GED | 22 (24) | 5 (23) | 332 (26) |

| Technical School | 11 (12) | -- | 63 (5) |

| Some college | 23 (26) | 10 (18) | 337 (27) |

| Bachelors degree | 15 (17) | 4 (18) | 247 (20) |

| Graduate Degree | 3 (3) | -- | 120 (10) |

| Income | |||

| ≤$15,000 | 58 (64) | 8 (36) | 234 (19) |

| $15,001-$20,000 | 9 (10) | 2 (9) | 100 (8) |

| $20,001-$30,000 | 11 (12) | 3 (14) | 141 (11) |

| $30,001-$45,000 | 4 (4) | 2 (9) | 160 (13) |

| $45,001-$60,000 | 3 (3) | 3 (14) | 136 (11) |

| >$60,000 | 3 (3) | 1 (5) | 361 (29) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | -- | 11 (50) | 602 (48) |

| Unemployed | -- | 3 (14) | 160 (13) |

| Self-Employed | -- | 3 (14) | 147 (12) |

| A Student | -- | 2 (9) | 80 (6) |

| Retired | -- | -- | 155 (12) |

| Unable to work | -- | 3 (14) | 117 (9) |

| Incarceration history | |||

| No | -- | 15 (68) | 989 (78) |

| Juvenile Detention | -- | 2 (9) | 31 (3) |

| Prison | -- | 5 (23) | 199 (16) |

| Juvenile Detention and Prison | -- | -- | 45 (4) |

Note. There is a small amount of missing data for several of the variables and, as a result, the percentages do not add up to 100.

Procedures

Community Advisory Board

The research team assembled a local community advisory board (CAB) of seven members representing a diverse cross-section of the local Atlanta Black community across gender, sexual orientation, education, and religious affiliations. In collaboration with the investigative team on a quarterly basis, the CAB reviewed the progress of the research, measures, discussed findings, provided input on data collection, and advised how best to disseminate study results to the community. CAB participants received a $50 gift card per meeting for their participation.

Data collection

The team conducted 90 semi-structured individual interviews with Black men between April 2010 and August 2010 that explored three topics relevant to participants’ HIV risk and protective behaviors: (1) psychological determinants of health (e.g., perceived stress, depression, gender role conflict); (2) culturally-specific coping strategies; and 3) HIV-risk-promoting/protective behaviors (condom use, HIV testing). The semi-structured format provided interviewers with the flexibility to utilize probes to further discuss relevant topics that emerged during the interview (Patton, 1987). Interviews, which lasted approximately 60 to 90 minutes, occurred in private areas such as offices, school conference rooms and hotel meeting rooms, were digitally recorded, and professionally transcribed. The interviewers were 3 Black men and 1 White woman who were trained on qualitative interview techniques using didactic and role-play approaches. At the time of the interviews, the 3 Black men were Ph.D.-level psychologists and each had more than 10 years of HIV research experience in recruitment and more than 5 years of interviewing experience. The white female interviewer was a third-year medical student who had experience in general medical interviewing techniques, and was trained in qualitative interviewing for this project. We decided to use predominantly Black men interviewers in order to increase the chances that participants were comfortable with the interviewing process as a result of sex and race match. Past research suggests that matching on these identity dimensions contributes to more frank and less socially desirable responses than those elicited with racial and sex discordant interviewer-participant pairings (see Krysan & Couper, 2003). Participants received a $50 gift card as an incentive for participation, and a list of resources for local social, medical, and mental health services. This protocol was approved by both Emory University’s Institutional Review Board and the Georgia Research Oversight Committee (GROC). Field notes and transcripts were imported into NVivo 8, a qualitative software package for analysis.

Reliability of qualitative methods

We utilized numerous methods for quality assurance and consistency of both qualitative data collection and analysis. First, we ensured that the entire research team was trained according to protocols of qualitative interviewing utilized in previous research (Malebranche et al., 2009). These training protocols involved Dr. David Malebranche, the sixth author, conducting 2 training sessions of 2 hours each with all interviewers to ensure equal knowledge of methodologies and approaches. In addition, he conducted mock interviews in which the interviewers played both interviewer and interviewee roles with each other and then conducted additional interviews with individuals outside of the research team (e.g., family members, friends). The mock interviews with the research team were transcribed and reviewed by the sixth author, the CAB, and the research team. Each interviewer received verbal feedback based on these reviews regarding their strengths and areas needing improvement. We reviewed and revised the interview guide for appropriateness, length of interview and flow of questions based on the mock interviews, and the interviewee’s perceptions of the questions and interview structure. At the end of this iterative process, the final interview guide reflected input and review from the CAB, members of the research team and members of the population being studied. Dr. Malebranche cleared interviewers to conduct interviews once this process was completed.

Qualitative analysis

The foci of our analysis were responses to a question about police and law enforcement experiences, “What are your general thoughts about policemen and law enforcement?” along with a probe, “Tell me about an experience you have had with a police officer.” We used strategies from Grounded Theory (Glaser & Strauss, 2009) and Thematic Analysis (Braun, Clarke, & Terry, 2014) to analyze the qualitative data. In line with this approach, we conducted three types of coding: open, axial, and selective. Open coding involved documenting first impressions and ideas of the data as well as systematically labeling the data with brief in vivo (e.g., verbatim) or conceptual code labels (e.g., “5-0 [slang for police] experiences”). All codes were post-hoc based on trends observed in the data and defined in a codebook with a coding lexicon shared by all members of the research team. During axial coding, we suggested and verified relationships between the codes generated in open coding through the use of detailed notes in paragraph form. Finally, we conducted selective coding in which we integrated codes (e.g., “racial profiling as a means of policing”) around a core theme (e.g., “discrimination experiences with police or law”), and identified categories that needed refinement. For the purpose of this study, selective coding involved more in-depth analysis of a matrix of similarities and differences in codes associated with police experiences and themes.

At the outset of final stage of the analysis, the four coders independently coded three interviews using a standard set of codes developed from the aforementioned process. All discrepancies between codes were discussed and resolved during team meetings. After inter-coder reliability was determined (k > .80), the research assistants coded the remaining 87 interviews. This method of establishing agreement among coders is consistent with methods described in the qualitative data analysis literature (Patton, 2002).

Results

Fifty of 90 participants mentioned negative experiences with police and/or law enforcement contact. Thus, although the question (“What are your general thoughts about policemen and law enforcement?”) and probe (“Tell me about an experience you have had with a police officer”) about police in the interview were neutral, many participants discussed negative experiences with law enforcement. Among the 50 participants who mentioned negative experiences, we grouped 34 of their specific narratives that were relevant to the experiences we classified into 8 distinct2 dimensions of negative experience. These 8 dimensions included: being accused of drug-related behavior, being unfairly pulled over while driving, being unfairly stopped and searched, being assumed a thief, experiencing verbal abuse, experiencing physical abuse, unfair treatment associated with attire, and being unfairly arrested.

Being accused of drug-related related behavior included police officers communicating their suspicions that participants had been using or selling drugs (e.g., questioning the participant about drugs, searching the participant for drugs). Among the coded experiences, one participant described an unfair experience with police accusing him of buying drugs shortly after moving to a new neighborhood:

…[I was] walking down the street and some people was selling drugs in this car and so when I walked by they hollered at me and I stopped and talked to them for a minute so they got out and introduced theyself and told me what they was selling and stuff but the police was watching these guys…All the time and neither of us knew it so I introduced the guy and I gave him dap, shook hands with him and I turned around and walked back the way I came, but when I got like a block away the police was waiting on the corner and they snatched me off the sidewalk behind the building and uh she insisted that I had drugs, which I didn’t…

Being unfairly pulled over while driving included experiences of having police officers pull them over in a car even though they had not violated any laws. An example of this is represented in an account from a participant who stated he had been pulled over, although he had not committed any traffic offenses, because he was profiled as a young, Black man:

Yeah like the police. The police, they do a lot of that. They see me, young, black male and they just label me before they even like… before they can even like know me they just label me. Pull me out of the car, they want to search me, want to do all of this and that and we just… we not doing nothing.

Being unfairly stopped and searched included being targeted (e.g., followed) and physically searched by the police with no perceived reason. One participant discussed an instance in which he was sitting in his driveway when a police officer drove up and searched him in relation to an unknown crime:

I remember our mother had just pulled up and the police were like, “What ya’ll doing right here?” and I was like, “Nothing, we’re sitting in front of the house talking and uh… waiting on my momma to get home.” And soon as he asked me that she was pulling in the driveway. And it’s just the fact that he just… he just didn’t have no probably [sic] cause or nothing. He just wanted to search me and run my name and when he found out my name was clean he wanted me to…he wanted to go through my pockets and…I’m like, “Okay I know you got to do your job, but you pushing it a little-little too far because I don’t have no weapons; no drugs or anything. All I got is a little money in my pocket.”

Being assumed a thief included police officers’ suspicions that participants had stolen or were about to steal (e.g., following participants around stores, telling participants that they fit the description of robbery suspects). Among the quotations coded, an interviewee described an experience in which an officer showed up at his house because he suspected the participant of robbing a store, although he had not committed the crime:

Uh…uh…I’ve been accused of uh… Let me see. This [officer] come to my house one day and said… Oh, I have been accused of what? Oh, of stealing something, of being in here stealing something from a place when I wasn’t even there or nowhere near the area at the time, right. And this cop went over to my house and said, “Come on out. I need to arrest you….somebody told me…” My mom was like, “No, he was here all night. He didn’t go nowhere.”

Experiencing verbal abuse included the participants’ reports of police officers being verbally hostile, rude, demeaning, or otherwise disrespectful (e.g., calling them names, threatening to arrest the participant without reason). One participant recalled being stopped and verbally accosted by the police when he was younger because the officers suspected him of a crime he did not commit:

I remember on Halloween, getting stopped by the police for throwing paint balls at somebody or shooting them at somebody and the police were extremely rude and uh you know, saying that they were gonna take me and my friend to jail or whatever else until we showed them our high school ID’s that were from like this extremely wealthy private school in the city and so they were like, ‘Oh, oh. I’m sorry. I have a friend’s friend son that goes there.’ And like, ‘Do you know so and so?’ Blah, blah, blah. ‘I’m really sorry, you know. We’re gonna let you go.’ Like, ‘Have a good day,’ kind of thing.

Experiencing physical abuse included reports in which police officers used unwarranted physical force (e.g., slamming them on the pavement). One of the participants indicated that he had experienced excessive physical force from police/law enforcement several times before and stated, “Officers do abuse the law. They do uh, use too much [physical] force and they just strictly just abuse their power.”

Unfair treatment associated with attire included participants’ cns of a participant while approaching them). One participant commented that he gets stereotyped by police for wearing baggy clothes, “I do wear baggy clothes. I always wore baggy clothes. I like my t-shirts extra-large. I got my own reason for doing that but I know I look a certain way to certain people.”

Being unfairly arrested included reported participants’ perceptions that they had been arrested without due cause. For example, a participant described being arrested for simply being in a high-crime neighborhood that was well-known for drugs:

Uh, uh what do they call it uh being in the wrong place, being in … DC6 they call it uh being in a drug area; so you ain’t necessarily got to be using drugs just know somebody over there in that area, somebody having a cookout and you know you over there at the cookout and you can end up going to jail uh because you in a drug area.

Additional quotes for each dimension can be found in Table 2. In addition to negative experiences, there were also several counter-narratives to the negative experiences that several participants described. Specifically, 5 of the 50 participants mentioned positive experiences with police and law enforcement. For example, one participant described a positive experience in which law enforcement officers worked hard to get him out of prison:

Well, my experience with the law, uh, some of it been good…Because if it wasn’t for some of the detectives that really believed in me, I would still be in prison…and for them to go to bat for me, to speak up for me on my behalf, was a good feeling and, and was a blessing

Table 2.

Sample Quotes from Qualitative Interviews with Black Men (N =90) in Study 1 and the Quantitative Items Developed for Study 3

| Item | Item wording | Exemplar quote |

|---|---|---|

| Filter Item | Have you had any experiences with police or law enforcement in the past 5 years? | N/A |

| D10 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement accused you of having or selling drugs? | “… Man them guys. I mean, I don’t know if they are still racists or if they think just ‘cause dope boys have the cars with the rim on them and all, stuff like that. We have had so many encounters with that. I mean, they [police] just stop us and want to check the whole car. They don’t find nothing. They take all the stuff out of the dashboard, leave it on the floor, stuff like that. Trying, trying to find something… yep. But um, I guess because drug dealers have the same cars and stuff like that.” |

| D20 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement pulled you over for no reason while you were driving? | “Man [police are] crooked man, I think, I think, well I ain’t gonna say they crooked… let me rephrase that; they over exaggerate let me say that, they over exaggerate because I mean…‘Hey why’d you pull me over?’ ‘[The officer said], you got a broken taillight.’ ‘[I said], I don’t got a broken taillight.’ Pow… ‘[The officer said], you do now. Come on get out the car.’…but I mean there’s really no need for other than the crime rate, for you to, to govern me.” |

| D30 | In the past year, how often have police or law enforcement stopped and searched you for no reason? | “Just three weeks ago I’m on my way home and the Atlanta police jump out on me and basically harass me and everything and search me and all of this other stuff just because they felt like I fit the bill.” |

| D40 | In the past year, how often have police or law enforcement assumed you are a thief? | “…sometimes when you go in stores, if you’re not dressed like in business casual, [the police], they’ll follow you around and look at you like you’re about to steal something.” |

| D50 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement been verbally abusive to you? | “They just come up there, they want to clear it out just because they want to clear it out. You know, everybody need to go home and then like sometimes, to me, some police officers they are so disrespectful in the way they talk to you and stuff, that they don’t talk to you with a good tone. They just so disrespectful in tone. Instead of talking to you like a person. So that will make you get offended and then there is a whole mess right there.” |

| D60 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement been physically abusive to you? | “I felt like you know when I was approached and uh, arrested I felt like I was uh, what’s the word to look for, it, it was excessive force um, I feel like that any citizen is allow to uh, ask questions and it’s…and…and…and expected to receive an answer from especially from a public servant or public official uh, I uh tried to ask questions about why I was being approached and I was physically a…a…abused b…b…because of that…you know I was uh, considered as being a smart ass and uh, thrown on the…thrown on the concrete scratched and you know face pressed down into the asphalt, and you know scratched my face up and everything, and, and thrown in the car and arrested. And I just felt like it’s definitely because I was black.” |

| D70 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement treated you unfairly because of how you dress? | “If I wear my clothes a certain way [police] put me in a box. They profile me and put me in a box … “Oh he… he must… he must be doing bad stuff. He must be selling drugs because his hair is like that or because his pants is halfway off his ass then he must be doing bad.” |

| D80 | In the past year, how often have police or law enforcement arrested you for something you didn’t do? | I get locked up for no reason because…I’m talking about this after I done got out of chain gang, you know, but they had locked me back up because I’m walking down the street, you know what I’m saying late at night… So you got another police pulled up and he like he looking for something and he talking about I must stole some crack. Stole it? Man you seen, did you see me throw anything? Lock me up for nothing, you know, try to put me in jail for no reason which you got to have some legitimate evidence saying I done done this you know and that’s what they do because all because you know of your background. |

Note. Rows in grey include quantitative items that were not administered as a part of Study 3, the quantitative study.

Study 2: Item Development and Qualitative Validation

Method

Procedures

Based on the results from Study 1 we created 11 Likert-type items that fit into one of the 8 dimensions based on the wording used by participants. Specifically, we identified key phrases from the data and used the participants’ own words to assist us in developing items. Examples of key phrases that we used to inform the development of the quantitative items used in the pilot study can be found in Table 2. We then evaluated these items using a 3-step approach that included focus groups, individual cognitive interviews, and pilot testing (Fowler, 1995).

Focus groups

We convened two focus groups during September 2010, one in Atlanta and one in Columbus, consisting of five Black men participants each to discuss and provide feedback on the newly developed survey items for the PLE, as well as other measures developed for use in the broader study examining HIV-risk-promoting/protective behaviors. Participants were recruited using community-based recruitment efforts similar to those indicated in Study 1. We asked focus group participants to consider two key elements of each item: (a) “Does the item accurately and adequately capture the reality of [your] experiences regarding (experiences with police and law enforcement)”?, and (b) “Is the item clear and unambiguous?” Focus groups also provided participants the opportunity to: offer their suggestions about how items should be phrased, note redundant or irrelevant items that should be omitted from the final survey instrument, and identify additional topic areas.

Individual cognitive interviews

We conducted individual cognitive interviews between September 2010 and October 2010 with a different sample of 15 Black men in Valdosta with the items that we revised following the focus groups. The goal of these cognitive interviews was to assess how well each item worked and the thought processes that participants employed when responding to each survey item. We recruited participants using community-based recruitment efforts similar to those used in Study 1. Participants were first asked to provide their numeric response to the item, then to paraphrase their understanding of the question. During this process, coders defined any unfamiliar terms, identified any uncertainty in participants’ responses, and asked how participants arrived at the numeric values they reported. Ten participants were asked to respond to each question, one-by-one, as they answered them. To emulate a typical survey administration, the remaining five participants completed the entire survey, revisited each question, and elaborated on the reasoning they used for their responses. The information gathered from these cognitive interviews enabled us to further refine our survey items prior to pilot testing. The changes that we made prior to pilot testing included deleting items and revising the wording of the items. As a result of these changes, we piloted 8 candidate items during pilot testing phase.

Pilot testing

We completed pilot testing during the period of November 2010 to December 2010 with a version of the PLE that was refined following the focus groups and cognitive interviews. We completed a formal pilot test with a convenience sample of 22 Black men who Dr. Malebranche and his research team recruited using snowball sampling starting with his personal and professional connections. The sample was comparable to that used in the larger quantitative study (Study 3) on key demographic variables such as the age range, education, employment status, annual household, and incarceration history (see Table 1). Of the participants in the pilot study, 13 responded “Yes” to the following filter question, “Have you had any experiences with police or law enforcement in the past year?” These 13 participants completed the 8 candidate items for the measure and provided feedback to the research staff regarding any issues they experienced with the instrument. Participants received a $25 cash incentive.

Results

Following the cognitive interviews and the focus groups, we adjusted the scale by changing the wording of existing items and deleting three items. An example of a wording change, was an item that we changed from if police and law enforcement “…assumed you are a thug” to “…assumed you are a thief.” We changed this because, although “thug” was a colloquial term used by participants in the qualitative interviews, we found that the term was a lexical ambiguity, such that participants reported many divergent connotations and definitions for the term. On the other hand the definition of “thief” was reportedly clear and unambiguous to the participants. In addition, we adjusted the question that asked about being pulled over by adding the phrase, “for no reason” to emphasize that it was unfair and, as such, discriminatory.

We also decided to delete two items that asked about the dimension associated with verbal abuse. The two items asked about whether the participants had been “treated disrespectfully” or “called racial names”. We decided to remove these items given conceptual overlap with the more global item that asked about whether police had been verbally abusive. Since the single item asking about verbal abuse was more parsimonious, we decided to retain that item in lieu of the other two items. Additionally, at the advice of participants, we decided to cut an item that fit into the being unfairly stopped and searched qualitative dimension that asked about whether participants had been followed by police/law enforcement for no reason. The participants in the cognitive interview stated that those items could be combined because being stopped and searched co-occurred with being followed by an officer.

In addition to providing advice on items to cut, participants offered several possible items that could be added to the PLE scale. Although we deemed these items pragmatically important to the participants, the candidate items did not fit the construct of interpersonal racial discrimination perpetrated by police and/or law enforcement. An example of one of these items was, “Response times longer based on geographical area call was placed from”, which we analyzed as indicative of systematic, structural inequality rather than interpersonal discrimination. As a result of these changes to the group of items, we tested 8 PLE items (one for each qualitative dimension) for the pilot study.

During the pilot study participants reported no major complications with the 8 candidate items. The descriptive statistics of the pilot reports are reported in Table 3. Following the pilot study, we revised the survey instrument by dropping 3 items (“In the past year, how often have police or law enforcement… 1. …stopped and searched you for no reason? 2. …assumed you are a thief? 3. …arrested you for something you didn’t do?”). The scale was shortened primarily as a means to reduce the length of the study protocol, which included several measures pertaining to HIV risk and protective behaviors, given concerns about participant burden. We chose to exclude the three specific items because results from the pilot study suggested that dropping these items would minimally to moderately improve the internal consistency of the scale, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha. Following the pilot study, we also altered the timeframe of the scale from one year to five years to incorporate distal, yet impactful, experiences with police and law enforcement. No other changes to items came from the pilot testing. The items presented in the white boxes of Table 2 and Table 3 are the final 5 items selected for the quantitative study following the review process described above.

Table 3.

Descriptive Results from Study 2 Pilot testing (n=13)

| Item | Item Wording | Mean | SD | Correlation with Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D10 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement accused you of having or selling drugs? | 2.08 | 1.19 | .89 |

| D20 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement pulled you over for no reason while you were driving? | 2.08 | 1.19 | .21 |

| D30 | In the past year, how often have police or law enforcement stopped and searched you for no reason? | 2.85 | 1.21 | .59 |

| D40 | In the past year, how often have police or law enforcement assumed you are a thief? | 2.15 | 1.21 | .48 |

| D50 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement been verbally abusive to you? | 2.62 | 1.33 | .65 |

| D60 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement been physically abusive to you? | 1.92 | 1.26 | .87 |

| D70 | In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement treated you unfairly because of how you dress? | 2.77 | 1.17 | .48 |

| D80 | In the past year, how often have police or law enforcement arrested you for something you didn’t do? | 2.00 | 1.35 | .68 |

Note. Rows in grey include quantitative items that were not administered as a part of Study 3, the quantitative study.

Study 3: Quantitative Reliability and Validity Testing of Police and Law Scale

Method

Participants

Participants were 1264 self-identified Black men who ranged in age from 18 to 65 (M =43.99, SD = 14.36). Key demographic data for these participants is featured in Table 1.

Procedure

Interviews

Data collection was completed over the phone utilizing Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) technology during the period between January 2011 to October 2011. Trained interviewers conducted the interviews. Interviewers were screened initially for voice quality, phone presence and adherence to instructions and then passed a mock interview. We recruited participants for this study by calling a random sample of households with telephone line access in four Georgia counties (Fulton, DeKalb, Lowndes & Muskogee) located within three metropolitan areas (Atlanta, Columbus & Valdosta). We utilized several frames to increase coverage and improve our chances of screening for eligible Black males.

Participant selection and eligibility requirements

To be eligible to participate in this study, the selected telephone number needed to reach a respondent who lived in a household within one of the four designated counties. There also needed to be at least one Black man between the ages of 18 and 65 residing within the home. If there was more than one age eligible Black male adult present, one was randomly selected to participate in the study.

Measures

Demographic Variables

Data was collected on the age, income, education, employment and incarceration history of each participant. Age was measured as a continuous variable; annual income before taxes was a categorical variable with responses ranging from 1 (15,000 or less) to 6 (More than 60,000); education was a categorical variable with responses ranging from 1 (Less than high school degree) to 4 (College degree or higher); employment was a dichotomous variable (0 = Unemployed/unable to work; 1 = Employed or student); and incarceration was a dichotomous variable (0 = Never Incarcerated; 1 = Incarcerated at least once before). Means, standard deviations, and ranges for these variables can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlations between Demographic Variables and PLE items, Study 3 with Black men (N = 1264)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1.0 | |||||||||||

| 2. Income | .14** | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| 3. Education | .11** | .51** | 1.0 | |||||||||

| 4. Employment | -.08* | .47** | .34** | 1.0 | ||||||||

| 5. Incarceration | -.04 | -.28** | -.26** | -.17** | 1.0 | |||||||

| 6. Full Scale PLE | -.25** | -.07** | -.02 | -.00 | .25** | 1.0 | ||||||

| 7. Filter Question | -.18** | .05 | .08** | .07* | .16** | .59** | 1.0 | |||||

| 8. Selling Drugs (D10) | -.25** | -.12** | -.10** | -.03 | .26** | .77** | .38 ** | 1.0 | ||||

| 9. Pulled Over (D20) | -.19** | -.02 | .07* | .02 | .14** | .83** | .61** | .53** | 1.0 | |||

| 10. Verbal Abuse (D50) | -.14** | -.03 | .04 | -.01 | .21** | .82** | .50** | .49** | .59** | 1.0 | ||

| 11. Physical Abuse (D60) | -.10** | -.07* | -.05 | -.01 | .23** | .64** | .31** | .44** | .36** | .52** | 1.0 | |

| 12. Clothes (D70) | -.27** | -.07* | -.07* | .00 | .20** | .84** | .45** | .58** | .61** | .57** | .46** | 1.0 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mean | 43.99 | 3.84 | 2.85 | .75 | .22 | 1.36 | .50 | 1.29 | 1.59 | 1.42 | 1.14 | 1.38 |

| SD | 14.36 | 1.93 | 1.03 | .43 | .41 | .61 | .50 | .76 | .97 | .84 | .46 | .84 |

| Range | 18-65 | 1-6 | 1-4 | 0-1 | 0-1 | 1-3.8 | 0-1 | 1-4 | 1-4 | 1-4 | 1-4 | 1-4 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01

Police and Law Enforcement (PLE) scale (α = 0.87)

Based on the Study 1 and Study 2 qualitative and quantitative pilot study findings, we included a total of 5 items in the PLE. The PLE asked respondents to report the frequency with which they had experiences with police and law enforcement. Prior to being administered these five items, each participant responded to a filter question “Have you had any experiences with police or law enforcement in the past 5 years?”, with response options: No, Yes, Don’t Know, Refuse to Answer. Participants who indicated “Yes” were then administered the 5 PLE items. The CATI was programmed to skip the 5 PLE items for those who responded No, Don’t Know, or Refuse to Answer. Participants who indicated “No” had their responses automatically coded as “Never” for the 5 PLE items. Participants who indicated “Yes” responded to the PLE items on a 6-point Likert-type scale that assessed the frequency of the reported experiences (1 = Never to 6 = Always). The descriptive statistics for the PLE items are included in Table 4.

Adofo racial discrimination measure (α = 0.86)

This 10-item instrument measures the frequency of unfair treatment due to racial discrimination in respondents’ daily lives. The measure was developed concurrently with the PLE with an identical exploratory sequential mixed methods design (Creswell et al., 2011). Sample items include: “because of your race or racism, how many times in the past year have you…Been followed in stores?” and “because of your race or racism, how many times in the past year have you…Had people lock their car doors when you pass by?” Several items overlap with the commonly-used and validated discrimination scales detailed in Williams, Yu, Jackson, and Anderson (1997) including being treated unfairly at work or fired from a job, being called names, being denied employment, and receiving poor service in restaurant or stores. Respondents used a 4-point scale (Often, Sometimes, Rarely, Never) with one “Don’t Know” option and a “Refuse” option. We reverse-scored all items so a higher score represented higher perception of unfair treatment. The full scale can be found in the Appendix section. This measure displayed concurrent validity with the PHQ-9 depression scale with a correlation of r = .38, p < .001. Also, a confirmatory factor analysis suggested that a one-factor model for the measure fit the data adequately χ2(35) = 159.75, p < .001; TLI = .89; CFI = .92; RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.05, .06].

PHQ-9 depression (α = 0.84)

The Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) includes 9 items assessing the frequency of each of the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorders covered in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM–IV). Scale items are rated on a 4-point scale (1 = Not at All; 4 = Nearly Every Day) according to the increased frequency that a participant has experienced each item over the past two weeks. Scores are summed and can range from 9 to 36. Higher scores represent a greater number of depression symptoms. A confirmatory factor analysis suggested that a one-factor model for the measure fit the data adequately, χ2(20) = 74.56, p < .001; TLI = .92; CFI = .94; RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.04, .06].

Analytic plan

Completed all analyses with data from the participants who endorsed the filter question and received the 5 PLE items (n=633). We weighted all analyses to adjust for nonresponse and coverage bias in the sampling frame. Normalized sample weights were computed in accordance with standard methods for probability sampling (e.g., Kalsbeek & Agans, 2008; Kalton & Flores-Cervantes, 2003; Lessler & Kalsbeek, 1992). In order to confirm the one-factor structure of the five PLE items, as was suggested by the common theme in the qualitative analyses, we ran a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) within Mplus 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2015) among the sample of the participants who endorsed the filter question (i.e., “Have you had any experiences with police or law enforcement in the past 5 years?”; n=633).

We correlated the PLE scale with demographic variables to test for associations across individual characteristics. We also tested the invariance of the factor structure (configural invariance), the factor loadings (metric invariance), and both the factor loadings and intercepts (scalar invariance) across participants with a history of incarceration and without a history of incarceration using the GROUPING command and maximum likelihood estimation within Mplus. To compare the model fit of these models we used a robust chi-square test (Satorra & Bentler, 2001). We conducted structural equation modeling on the sample that endorsed the filter question (n=633) to validate the concurrent validity and convergent/discriminant validity of the PLE scores. Model fit was evaluated using the following indicators: probability of the chi-square statistic; the comparative fit index (CFI)>.90; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI)>.90; and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)<.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Correlations between demographic variables and the PLE items

Table 4 shows the correlations between the demographic variables and the PLE items, including the filter question (“Have you had any experiences with police or law enforcement in the past 5 years?”). Younger men reported higher scores on all of the PLE items, including the filter item, compared with older men. Men who reported lower incomes reported more of the full scale PLE experiences and more accusations of drug abuse, more physical abuse, and more unfair treatment because of attire than men who reported higher incomes. Men with less education reported experiencing more accusations of drug abuse, being pulled over, more unfair treatment because of attire, and more general experiences (as indicated by the filter item) than did men who reported more education. None of the PLE items correlated with employment status, although the filter question was positively associated with employment — albeit at a low effect size (r = .07, p < .05). Men with histories of incarceration reported experiencing higher frequencies of all the PLE items, including the filter item, compared with men without an incarceration history.

Factor analyses and measurement invariance

Descriptive statistics for the PLE items are provided in Table 5. The CFA on the participants who endorsed the filter item (n = 633) indicated that the one-factor solution fit the data adequately, χ2(5) = 22.12, p < .001; TLI = .89; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .07, 90% CI [.04, .11]. All items loaded .50 or higher on a single factor for both models (see Table 5 for factor loadings). The standardized Cronbach’s alpha for the sample was .87.

Table 5.

Confirmatory factor analysis loadings of PLE scale items, Study 3 (Quantitative Phase) with Black men (n = 633)

| Police and Law Enforcement Scale | CFA Factor Loading | Mean | SD | Alpha with Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem: In the past 5 years, how often have police or law enforcement … | ||||

| 1. …accused you of having or selling drugs?(D10) | 0.68 | 3.43 | 0.99 | 0.72 |

| 2. …pulled you over for no reason while you were driving?(D20) | 0.61 | 2.82 | 1.08 | 0.73 |

| 3. …been verbally abusive to you?(D50) | 0.65 | 3.17 | 1.02 | 0.71 |

| 4…been physically abusive to you?(D60) | 0.52 | 3.72 | 0.62 | 0.75 |

| 5…treated you unfairly because of how you dress?(D70) | 0.78 | 3.24 | 1.07 | 0.69 |

Note. Standardized estimates provided.

The test of configural invariance across incarceration history produced an adequate overall model fit, χ2(10) = 34.68, p < .001; TLI = .92; CFI = .96; RMSEA = .06, 90% CI [0.04, 0.09] and all loadings were positive and loaded onto one latent variable in a similar pattern across groups (i.e., incarcerated vs. never incarcerated). To test for metric invariance — that the factor loadings are invariant across the groups — a nested model where all loadings were constrained to be equal across groups was compared to the free, configural model. Overall, the model fit for the nested metric model was good, χ2(14) = 44.21, p < .001; TLI = .93; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .06, 90% CI [0.04, 0.08]. The robust chi-square test difference score indicated that the loadings of the indicators were not significantly different across groups, χ2diff (4) = 9.10, ns. To test for scalar invariance—that the factor loadings and intercepts were invariant across groups—a nested model where all loadings and intercepts were constrained to be equal across groups was compared to the free, configural model. The model fit for the nested scalar model was acceptable, χ2(18) = 60.77, p < .001; TLI = .92; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .06, 90% CI [0.05, 0.08]. However, the robust chi-square test difference score indicated that the loadings of the indicators were significantly different across groups, χ2diff (8) = 25.70, p<.01, suggesting that levels of the underlying items (intercepts) are not equal in both groups. This was anticipated, however, because men with histories of incarceration reported experiencing higher frequencies of all the PLE items as compared to men without an incarceration history. Therefore, we found evidence for both configural and metric invariance across participants with versus without a history of incarceration, though we did not find support for scalar invariance.

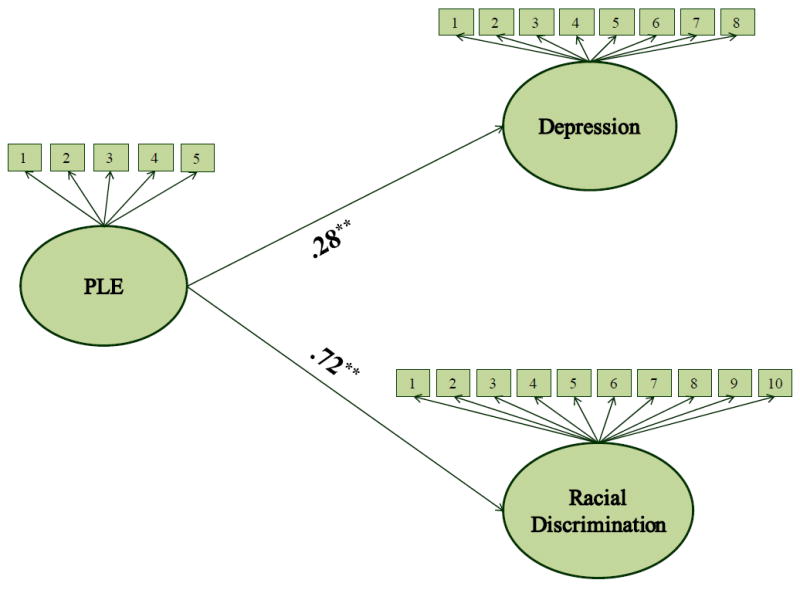

Validation structural equation model

We assessed validity by running a SEM with the PLE as a predictor of depressive symptoms and racial discrimination with the sample of 633 participants (See Figure 1). The model fit was adequate, χ2(227) = 511.87, p < .001; TLI = .91; CFI = .92; RMSEA = .05, 90% CI [.04, .05]. Within this model, concurrent validity was established as displayed by positive associations between the PLE latent variable and depressive symptoms (β = .28, p < .01). We assessed convergent validity by including a pathway between the PLE latent variable and a racial discrimination latent variable. PLE scores were positively associated with reports of racial discrimination (β = .72, p < .01). To test discriminant validity, we compared a separate SEM model in which the path between the racial discrimination latent variable and the PLE latent variable was constrained to one and another SEM model with the path freed. A robust chi-square difference test comparing these models indicated that the model with the freed correlation fit the model best χ2diff (1) = 55.83, p<.001. This suggests that the PLE measure and the racial discrimination measure are related, yet are distinct constructs.

Figure 1. Validation Structural Equation Model with the PLE and Validation Measures, Study 3 (Quantitative Phase) with Black men (n =633).

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01

Standardized estimates provided.

Correlations between outcome variables no shown. All are significant and positive.

To follow up on the results of the structural equation model we decided to tested for differences in the levels of depressive symptoms and racial discrimination between those who endorsed the filter item and those who did not. T-test analysis comparing racial discrimination between the group of people that endorsed the filter item (M=2.03, SD=.69) and those who did not endorse the filter item (M=1.64, SD=.60) indicated the group that endorsed had statistically significantly more racial discrimination experiences, t(1236.52)=-10.85, p <.001. In addition, a t-test analysis comparing depressive symptoms between the group that did not endorse the filter item (M=1.56, SD=.62) and those who did endorse the filter item (M=1.69, SD=.64) showed that those who did endorse the filter item had statistically significant more depressive symptoms, t(1257)=-3.60, p<.001. Both of these results provide additional evidence for the validation SEM as they indicate more PLE experiences are associated with more racial discrimination experiences and depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The recent widespread protests in the United States around the issue of police discrimination towards Black men underscores the necessity for tools such as the Police and Law Enforcement (PLE) scale. Echoing past calls to end racial discrimination among police and law enforcement bodies (e.g., Diallo & Wolff, 2004), leading civil rights advocates have cited the damaging effects of discrimination on Black men and their communities. Although a sound body of social science research, including psychological, sociological, and criminological studies, supports these claims, there is a scarcity of research investigating the way in which police-perpetrated discrimination affects the psychological outcomes for Black men. Guided by research that posits the individual’s perspective as central to the stress process (e.g., Clark et al., 1999; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), we developed the PLE scale to provide a foundation from which to examine outcomes among Black men who report experiencing discrimination from police and law enforcement. Thus, through this mixed-methods study we developed a multi-item, self-report psychometric instrument that assesses the frequency of police-based discrimination for Black men.

While the broader project from which this study emerged was initially aimed at identifying Black men’s perceptions of mental health and individual HIV risk behaviors, the topic of police-related experiences was a common theme throughout the qualitative interviews and focus groups. In particular, 50 out of 90 participants discussed the unfair treatment they had experienced during interactions with police/law enforcement in response to a general question about police experiences. From these interviews, we developed and refined a five-item scale to assess experiences of police discrimination frequency across five types of unfair treatment: accusations of drug-related behavior, being pulled over while driving, experiencing verbal abuse, experiencing physical abuse, and unfair treatment associated with attire. The psychometric qualities of the developed scale were tested using self-report survey data from 1264 Black men in Georgia. Over half of these participants (n=633) reported having had any experiences with police or law enforcement in the past 5 years and were, therefore, presented with the PLE items. The scale showed strong psychometric properties, with high internal consistency, concurrent and convergent/discriminant validity, and measurement invariance between formerly-incarcerated men and those without a history of incarceration.

The study supported our hypothesis that men with higher PLE scores would have higher depressive symptom scores. This finding is consistent with empirical evidence documenting the positive association between Black men’s experiences with discrimination and depressive symptoms (Brown et al., 2000; Hammond, 2012; Pieterse & Carter, 2007; Utsey, 1997; Watkins et al., 2011). Discriminant and convergent validity were established through an association between the PLE and an original measure of racial discrimination (i.e., Adofo Racial Discrimination Measure) that reached a moderate-high level (β= .72) and analyses that showed that the racial discrimination and the PLE measures assessed related, yet separate, constructs.

Measurement invariance analyses revealed that the PLE scale measures a construct that occurs similarly among Black men who have a history of incarceration and those who do not. As such, the PLE appears to measure a phenomenon that occurs commonly among Black men, a conclusion that validates past studies showing that Black men from diverse backgrounds and circumstances have disproportionately common experiences with police and law enforcement that range from “Driving while Black” (e.g., Brunson & Miller, 2006a; Brunson & Miller, 2006b; Hurst et al., 2000) to being verbally or physically harassed (e.g., Bell et al., 2014) or killed by police (Bulwa, 2010; New York City Police Department, 2012). Overall, the present study shows that the PLE scale is a tool that can be utilized to effectively measure the frequency of Black men’s experiences of discrimination from police and law enforcement.

The results of this study complement the existing literature by providing self-report evidence that Black men report frequent discrimination from police (Bell et al., 2014; Brunson & Miller, 2006a; Brunson & Miller, 2006b; Dowler & Sparks, 2008; Farrell et al., 2004; Gabbidon, 2003; Gelman et al., 2007; Hartney & Vuong, 2009; Hurst et al., 2000; Kochel et al., 2011; Muller & Schrage, 2014; Weitzer & Tuch, 2005) and that experiences of discrimination can be psychologically harmful (e.g., Brown et al., 2000; English et al., 2014; Klonoff et al., 1999; Krieger & Sidney, 1996; Krieger et al., 2011; Mays et al., 2007; Thompson, 2002; Utsey et al., 2002; Watkins et al., 2011; Williams & Mohammed, 2013). This is important because past research suggests that chronic exposure to race-related stress is associated with psychological dysfunction and indicators of allostatic load (e.g., elevated cortisol levels, epinephrine, norepinephrine, resting diastolic and systolic blood pressure, creatine levels, body mass index), a predictor of high early mortality rates among Black Americans compared to White Americans (Brody et al., 2014; Duru, Harawa, Kermah, & Norris, 2012). The present study also builds upon past results showing that police discrimination experienced by Black men is distinct from general racial discrimination experienced by Black men. This distinction may be explained by the fact that the PLE scale captures experiences at the intersection of race and gender, whereas most racial discrimination measures focus on race exclusively (Bowleg et al., 2016). It could also be that the experience of interpersonal racial discrimination differs from experienced police/law enforcement discrimination because of social context. For example, in a predominantly Black neighborhood, a Black man may not experience high rates of interpersonal racial discrimination from peers and neighbors, but may have frequent negative experiences with police officers, given the overrepresentation of police/law enforcement officials within Black neighborhoods (Carmichael & Kent, 2014). In addition, because reports of having unfair experiences with police/law enforcement were common among the participants in the qualitative and quantitative portions of the present study, the results bring light to the importance of collecting data on police-initiated contact/harassment, which has been historically neglected in policing statistics (Wines, 2014).

The study’s results are bolstered by the rigorous nature of the qualitative and quantitative analyses and survey development methodology that we used. Our research represents a culturally-grounded qualitative approach rooted in the experiences of Black men. Indeed, the content of each item of the PLE was identified and drawn from qualitative reports of a socioeconomically and geographically diverse sample of Black men living in Georgia.

These strengths must be considered in the context of the present study’s limitations, however. For example, the sample for our study was limited to a single southern state in the United States and, as such, our results may reflect police experiences that are unique to laws and culture in this geographic area. The applicability of the PLE scale to alternate contexts should be tested in future research with more geographically diverse samples. Additionally, it is possible that the 3 Black men interviewers, and 1 White woman interviewer in Study 1 elicited different qualitative content because of racial and/or gender concordance. However, it is important to note that including several Black men as interviewers in this study was also a strength because very few studies about Black men are conducted by Black men and, as a result, this may have allowed for more comfort with the interview process and more depth/honesty in responses due to a perceived shared racial and gender identity.

One weakness that affected the present quantitative estimates was the filter item we used (i.e., “Have you had any experiences with police or law enforcement in the past 5 years?”). If the participants responded “no” or “do not know” to this item they did not view the five specific PLE items. This survey design is problematic because it asks about a general experience (“any experience”) over a large reference period (5 years) and, as such, relied heavily on the recall and comprehension of the participant (Tourangeau, Rips, & Rasinski, 2000). On the other hand, the five PLE items ask about more specific experiences, which are easier to encode and recall. Another limitation of the present research, is that we used a measure of racial discrimination developed from the same sample to assess validity. Although the Adofo racial discrimination measure displayed internal consistency and construct validity in the present study, future research with the PLE scale could utilize a widely-used measure of racial discrimination such as the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams et al., 1997), to bolster the evidence of validity. In addition, the present sample was an older sample, as the average age was 44 years old. This is a limitation because past studies (e.g., Pew Center on the States, 2008) suggest that younger Black men (18-25 years old) experience the highest rates of police profiling. As such, it is likely that the present frequency estimates may underestimate Black men’s encounters with police and law enforcement. The PLE scale should be used with young adult samples in future research and can be tested with children younger than 18 years old to assess the applicability of these experiences to the lives of children and adolescents. Recent research with adolescents suggests that they are commonly perceived and treated as adults by police officers (Goff et al., 2008; Goff et al., 2014) and, as a result, may be having PLE experiences with comparable or greater frequency than adults.

Although we used the filter item in this study, future research using the PLE scale would benefit from considering dropping the filter item, as this would provide for more precision in frequency estimates. This is particularly advisable as the five items add negligible participant burden given their brevity. However, it is worth noting that given the brevity of the measure it likely does not encompass all potential, and probable, discriminatory experiences Black men have with police/law enforcement. This includes the three items that were featured in the pilot study and later excluded in Study 3, one of which was the most commonly endorsed among the 13 pilot study participants (“In the past year, how often have police or law enforcement stopped and searched you for no reason?”). Although we excluded these items from the larger HIV-prevention focused quantitative study primarily because of participant burden limitations, along with some evidence from the pilot sample that they may negatively affect the scale’s internal consistency, these items could be used by researchers who do not have such restrictions and are interested in gaining a more comprehensive perspective on police and law enforcement experiences.

Researchers should also consider utilizing shorter reference periods over which to assess Black men’s PLE experiences. Although this study asked participants to report on their experiences with police and law enforcement over the past five years, the five content-specific items assessing the frequency of police-perpetrated hassles may be more accurate with a smaller time frame (e.g., a year, months), as these shorter reference-periods aid in the accuracy of frequency recall (Tourangeau et al., 2000). Future studies should use the PLE scale in multi-wave longitudinal research to assess the psychological impact of self-reported police discrimination across time. In such studies, the PLE scale could be used to investigate the link between police discrimination and later health outcomes across time.

Although we focused on Black men in this study, police discrimination experiences do not apply exclusively to Black men. Indeed, there is a well-developed literature documenting the discriminatory treatment of Latino men by law enforcement, particularly with respect to the enforcement of immigration laws in border states (e.g., Menjívar & Bejarano, 2004; Negi, 2013; Romero & Serag, 2004). This treatment is also not limited to men, as sufficient evidence indicates that women of color, and particularly Black women, are disproportionately affected by police brutality and mass incarceration (Crenshaw & Ritchie, 2015; Pew Center on the States, 2008). In fact, among the outcry against the killing of unarmed Black men during 2014, there were calls to recognize the pain of Black women who are affected by police brutality (e.g., Gross, 2014). As such, measures like the PLE should be developed and validated for these groups.

Following recent years marked by anti-police discrimination protests, on the one hand, and police-support rallies, on the other, the need for informed dialogue regarding discrimination committed by police and law enforcement officials against Black men is more apparent than ever. Indeed, a clear understanding of the nature and scope of police-perpetrated discrimination is an important step in effectively addressing the problem. Such knowledge could have numerous important applied implications, including informing the development of culturally-specific coping resources for Black boys and men such as those associated with racial discrimination more broadly (see for example Elligan & Utsey, 1999; Utsey, Hook, Fischer, & Belvet, 2008; Utsey, 1997). The information gained from research with the PLE scale may also highlight the need for further education and training in police academies to reduce police prejudice and discrimination against Black boys and men. In addition, we believe that the PLE scale can make an important contribution to ongoing initiatives to increase racial equity in policing practices such as those supported by The Center for Policing Equity (CPE) based at UCLA (Center for Policing Equity, n.d.). Our hope is that the PLE scale can be used across a variety of disciplines and applied settings. Given the brevity of the measure and its strong psychometric qualities, it can be a relatively burden-free addition to research assessing psychological outcomes for Black men. The utilization of the PLE scale across research disciplines will add to the generalizability and cohesiveness of results and will provide a multi-angled perspective on the impact of police practices affecting Black men. As such, the PLE scale has the potential to produce valuable information on the psychological and physiological outcomes of Black men who experience police and law enforcement discrimination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Institute of Nursing Research (NR011137-01A2, PI: Malebranche) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (5F31DA036288, PI: English).

Footnotes

Throughout the production of this manuscript several other names could have been added to the list given ongoing killings of unarmed Black men and boys by police officers.

Although we initially identified 10 dimensions of experience, 2 of those dimensions were removed from consideration due to conceptual overlap with other dimensions.

References

- American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU] Attorney General says ending racial profiling is priority for Obama Administration. 2009 Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/news/attorney-general-says-ending-racial-profiling-priority-obama-administration?redirect=racial-justice/attorney-general-says-ending-racial-profiling-priority-obama-administration.

- Bell GC, Hopson MC, Craig R, Robinson NW. Exploring Black and White accounts of 21st-century racial profiling: Riding and driving while Black. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication. 2014;15(1):33–42. doi: 10.1080/17459435.2014.955590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmon DA. Slavery by another name: The re-enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York, NY: Random House LLC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L, English D, del Rio-Gonzalez AM, Burkholder GJ, Teti M, Tschann JM. Measuring the pros and cons of what it means to be a Black man: Development and validation of the Black Men’s Experiences Scale (BMES) Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2016 doi: 10.1037/men0000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V, Terry G. Thematic analysis. In: Rohleder P, Lyons AC, editors. Qualitative Research in Clinical and Health Psychology. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2014. pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Lei M, Chae DH, Yu T, Kogan SM, Beach SRH. Perceived discrimination among African American adolescents and allostatic load: A longitudinal analysis with buffering effects. Child Development. 2014;85:989–1002. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Gallo LC, Myers HF. Race, racism and health: Disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, Williams DR, Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, Sellers SL, Brown KT. Being Black and feeling blue: The mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race and Society. 2000;2(2):117–131. doi: 10.1016/S1090-9524(00)00010-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunson RK, Miller J. Gender, race, and urban policing. The experience of African American youths. Gender & Society. 2006a;20(24):531–552. doi: 10.1177/0891243206287727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunson RK, Miller J. Young Black men and urban policing in the United States. British Journal of Criminology. 2006b;46(4):613–640. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azi093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bulwa D. NAACP focuses on officer-involved shootings. SFGATE. 2010 Dec 17; Retrieved from http://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/NAACP-focuses-on-officer-involved-shootings-2453109.php.

- Carmichael JT, Kent SL. The persistent significance of racial and economic inequality on the size of municipal police forces in the United States, 1980–2010. Social Problems. 2014;61:259–282. doi: 10.1525/sp.2014.12213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carson EA. Prisoners in 2013 (No NCJ 247282) Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Policing Equity. Center for Policing Equity. n.d Retrieved from http://cpe.psych.ucla.edu/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2005 (Rev ed) Vol. 17. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/ [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54(10):805. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J. Be free. New York, NY: Dreamville Records; 2014. [Google Scholar]