Abstract

Orexins or hypocretins are neurotransmitters produced by a small population of neurons in the lateral hypothalamus. This family of peptides modulates sleep-wake cycle, arousal and feeding behaviors; however, the mechanisms regulating their expression remain to be fully elucidated. There is an interest in defining the key molecular elements in orexin regulation, as these may serve to identify targets for generating novel therapies for sleep disorders, obesity and addiction. Our previous studies showed that the expression of orexin was decreased in mice carrying null-mutations of the transcription factor early B-cell factor 2 (ebf2) and that the promoter region of the prepro-orexin (Hcrt) gene contained two putative ebf-binding sites, termed olf-1 sites. In the present study, a minimal promoter region of the murine Hcrt gene was identified, which was able to drive the expression of a luciferase reporter gene in the human 293 cell line. Deletion of the olf1-site proximal to the transcription start site of the Hcrt gene increased reporter gene expression, whereas deletion of the distal olf1-like site decreased its expression. The lentiviral transduction of murine transcription factor ebf2 cDNA into 293 cells increased the gene expression driven by this minimal Hcrt-gene promoter and an electrophoretic mobility shift assays demonstrated that the distal olf1-like sequence was a binding site for ebf2.

Keywords: orexin, basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors, early B-cell factor 2, promoter regulation, transcription factors, luciferase

Introduction

Orexins or hypocretins are peptide neurotransmitters expressed in a specific neuron population within the lateral hypothalamus of the mammalian brain (1,2). Orexins exert multiple effects in the central nervous system and modulate several important behaviors, including arousal, food intake, reward and the sleep-wake cycle (3–7). This neurotransmitter is part of a complex system, which receives and integrates multiple signals from metabolic, hormonal, neuronal and molecular origins (4,6,8–12).

Two orexin isoforms, orexin-A and orexin-B, are produced from a common precursor protein, prepro-orexin, through proteolysis (6). Prepro-orexin is encoded by the Hcrt gene, which contains 2 exons and 1 intron (13). This gene shows high sequence homology in mouse, rat and human genomes (95% homology between rat and mouse gene sequences and 82% homology between the mouse and human gene sequences) (14).

The region upstream of the transcriptional start site contains essential elements for correct hypothalamic expression (12,15–17) and for the binding of several transcription factors, including forkhead box A2 (Foxa2), insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 and the nuclear receptors, nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 (Nr4a1, also known as Nur77) and Nr6a1, which promote or repress the expression of the Hcrt gene (12,18,19).

Within this upstream region, two phylogenetically conserved elements (OE1 and OE2) direct the expression of the Hcrt gene in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) and repress it outside this region of the nervous system (16). It has been suggested that the proximal OE1 element, which is located 278 bp upstream of the putative transcriptional start site, is required to restrict the expression of Hcrt to the LHA, as this gene can be expressed in other areas of the hypothalamus in transgenic animals carrying mutated versions of this OE1 sequence (16). However, the regulation of orexin biosynthesis remains to be fully elucidated. There is an interest in understanding the key molecular elements in orexin regulation as these may serve to define potential targets to generate novel therapies for the treatment of eating and sleep disorders, and other disorders associated with motivation behaviors, including addictive behavior.

Our previous studies identified two putative olf-1 sequences within the OE1 element of the Hcrt gene promoter (20). These olf-1 sequences are targets for the ebf family of transcription factors (21). Our previous studies also revealed that mice carrying null mutations of the ebf2 locus show a narcoleptic phenotype, characterized by direct to rapid eye movement transitions from the wake state and cataplexy episodes (20). This phenotype is due to the loss of 80% of the orexinergic neurons in the LHA and decreased expression levels of orexin A in the remnant cells. Taken together, these results suggest that ebf2 is central in the correct development, expression and/or differentiation of the orexinergic circuit in the LHA (20).

Ebf transcription factors are also members of the basic helix-loop-helix protein family. Members of this family are known to be master regulators of neural differentiation and migration, and are involved in establishing particular gene expression profiles within the central nervous system, which lead to neural specialization. In particular, ebf2 regulates neurogenesis, the initiation of neural differentiation, migration and neural specification in the olfactory system, cerebral cortex and cerebellum (22–25).

The present study further analyzed the modulation of the expression of Hcrt by defining a minimal Hcrt gene promoter containing the proximal OE1 element, and examining the effects of mutating the olf-1-like elements present in this minimal promoter. In addition, the present study examined the effects of overexpressing ebf2 in 293 cells on the reporter gene expression driven by this minimal promoter.

Materials and methods

Sequence design and synthesis

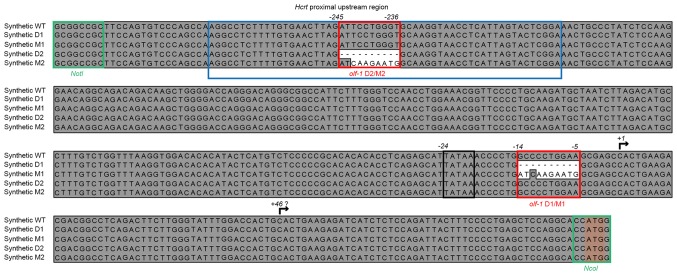

The proximal upstream sequence of the murine Hcrt gene was obtained from the Ensembl database (14). A 390 bp fragment upstream of the transcription start site was synthetically assembled (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA), in order to generate constructs containing the wild-type (WT) sequence and several different deletions and mutations in one or both putative olf1-like sites (Fig. 1). The putative transcription and translation start sites from the Hcrt gene were preserved, by introducing NcoI at the 3′-end of the sequence for cloning purposes. Finally, a NotI site was added at the 5′-end of the synthetic constructs for promoter replacement in the reporter gene vector constructs.

Figure 1.

Minimal murine Hcrt gene promoter and its synthetic derivatives. Modified DNA sequences were generated based on the proximal 5′ upstream region (~-390bp) of the mouse Hcrt gene, which included the complete proximal OE1 element (blue box). The modifications included deletions or mutations of olf-1 sites (red boxes) proximal (M1/D1) or distal (M2/D2) to the putative TSS of the Hcrt mRNA (indicated by an arrow). The TATAA box is outlined by a black box, whereas the initial ATG codon of Hcrt is highlighted by a light-orange box. Green boxes outline restriction enzyme sites added for cloning purposes. A second probable TSS was identified, indicated by a question mark above the arrow. TSS, transcription start site; WT, wild-type; D, deletion; M, mutation.

Reporter plasmids and expression vectors

The synthetic Hcrt promoter sequences were subcloned into the pNiFty3-Luc expression vector (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). This reporter plasmid encodes a coelenterazine-utilizing secreted luciferase and carries resistance to the antibiotic zeocin. The original interferon (IFN)-β minimal promoter of the vector was replaced and the synthetic Hcrt promoter sequences were inserted as NotI-NcoI fragments. The plasmids were purified through anion-exchange columns (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) and all vector constructs were quantified using a fluorescence method with the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell culture

The 293 cells were obtained from America Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). 293/ebf2 cells were generated by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA) through lentiviral transduction of the murine ebf2 cDNA sequence. The cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Caisson Laboratories, Inc., North Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Puromycin (0.5 µg/ml) and zeocin (0.4 mg/ml; InvivoGen) were added to the ebf2-overexpressing and pNifty3-carrying semi-stable cells, respectively, as selection agents.

Transfection and luciferase reporter assays

The cells were seeded in 96-well plates 1 day prior to transfection. The cells were transfected with Lipofectamine reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 100 ng of the reporter plasmids. Luciferase signal was measured 48 h following transfection using a Glo-Max multidetection system (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) with QUANTI-Luc luminescence assay reagent (InvivoGen). Semi-stable transfected cells were generated from these initial transient transfections by selecting the cultures under 0.4 mg/ml zeocin for 1 month, prior to assaying luciferase output. All luminescence signals were normalized by the number of cells present in each well during the assays. The viable cell number in each well was determined using an ATP-dependent kit (CellTiter-Glo; Promega Corporation). The concentration of secreted Lucia luciferase was determined using purified recombinant Lucia protein (InvivoGen) as a standard for the determination of enzymatic activity.

RNA isolation and relative expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the cell lines using PureZol RNA isolation reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) followed by RNA purification using the RNAeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (Qiagen) and quantification by ultraviolet spectrophotometry. Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis was performed with 1,000 ng of total RNA in 20 µl of GoScript master mix buffer via GoTaq Probe 2-Step RT-qPCR (Promega Corporation). The amplification of Ebf2 and GAPDH mRNA was performed with validated, species-specific hydrolysis probes labeled with FAM and HEX, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Integrated DNA Technologies). The amplification of Lucia luciferase mRNA was performed with two sets of amplification primers and a common hydrolysis probe (Integrated DNA Technologies), designed using the qPCR designer tool in MacVector software version 15.5.4 (MacVector, Inc., Apex, NC, USA), to determine the relative mRNA levels of luciferase starting at two different nucleotides. All primer and hydrolysis probe sequences are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Oligonucleotide sequences.

| Gene (species) | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Hydrolysis probe (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR | |||

| GAPDH (H. sapiens) | TGTAGTTGAGGTCAATGAAGGG | ACATCGCTCAGACACCATG | AAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTC |

| EBF2 (H. sapiens) | AGTCGATGCTGCGAAAAGAAAAG | CTTCTTGCTCTCCGTCCATGCTTGG | CGTCCTGGCTGTTTCTGACA |

| Ebf2 (M. musculus) | AGTCGATGCTGTGAGAAGAAGAG | CTTCTTGCTCTCCTTCCATGCTTAG | TGTGCTGGCTGTTTCTGACA |

| pHcrtWT-Lucia 5′ (+1) TSS | CATCTCTCCAGATTACTTTCCCCTG | CCTTATCCTTGAAGCCAGGAATCTC | AACACAGATGCTGACAGGGG |

| pHcrtWT-Lucia 3′ (+46) TSS | CATCTCTCCAGATTACTTTCCCCTG | CCTTATCCTTGAAGCCAGGAATCTC | AACACAGATGCTGACAGGGG |

| EMSA duplex | |||

| OE1 top | GCCTCTTTTGTGAACTTAGATTCCTG | ||

| GGTGCAAGGTAACCTCATTAGTAC | |||

| OE1 bottom | GTACTAATGAGGTTACCTTGCACCCAG | ||

| GAATCTAAGTTCACAAAAGAGGC | |||

qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; TSS, transcription start site; Ebf2, early B-cell factor 2.

All PCR amplifications were performed using 2 µl of the previously synthesized cDNA (equivalent to 100 ng of the total RNA input sample) in 50 µl of GoTaq PCR master mix, following a 2-step amplification protocol: A starting denaturing step for 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation for 15 sec at 96°C, and then annealing and extension for 1 min at 60°C using a LightCycler 480 Instrument II (Roche Applied Science, Branford, CT, USA). GAPDH was used as reference gene. The results were analyzed according to the 2−ΔΔCq method (26) and reported as the number of copies of the mRNA of interest per copies of the reference GAPDH mRNA.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

A biotinylated 50-bp duplex oligonucleotide was incubated with nuclear protein extracts from either parental 293 or 293-ebf2 cells with the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Nuclear proteins were obtained using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extractions Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The binding reactions, containing 3 µg of nuclear extract protein and 2 fmol of the biotinylated oligonucleotide in 20 µl of the recommended binding buffer, were run on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, and transferred onto a nylon membrane for 30 min at 15 V using a Transblot transfer SD cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and detected using the ChemiDoc MP system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as box plots, with the limits of the box indicating the 25 and 75% percentiles of the data distribution, the line in the center of the box indicating the median of the population, and the error bars indicating the 5 and 95% distribution percentiles. These percentiles overlapped with the 25 and 75% percentiles in certain figures due to the scales of the horizontal axes. Statistical comparison was performed by analysis of variance and post hoc Holm-Sidak tests using Sigmastat version 3.5 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). P<0.01 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Proximal 390-base-pair upstream sequence from the mouse Hcrt gene drives the expression of a reporter gene in 293 cells

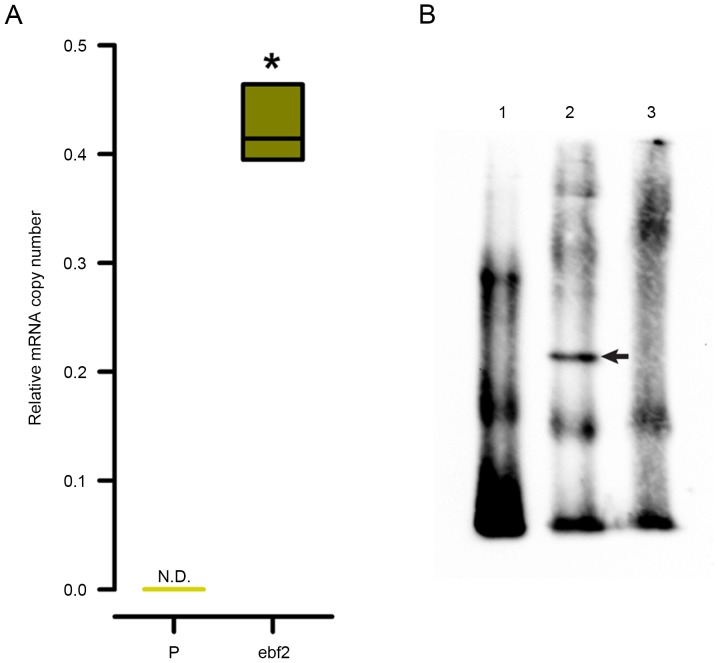

In the present study, a reporter gene vector, (pHcrtWT-Lucia) carrying ~390 bp of the proximal upstream sequence of the WT murine Hcrt gene promoter, was transfected into 293 cells. As shown in Fig. 2A (WT vs. IFN boxes), this small fragment of the Hcrt gene promoter induced ~100-fold higher levels of luciferase activity, compared with the IFN-β minimal promoter of the parental vector (pNifty3-Lucia).

Figure 2.

Expression of the luciferase reporter gene is driven by the different derivatives of the minimal Hcrt promoter. Luciferase signals from transiently transfected parental 293 (A, light green bars) and ebf2-lentiviral-transduced 293 cells (293-ebf2, B, dark green bars) showed that the expression of luciferase was driven by the different Hcrt promoter sequence derivatives. (B) Overexpression of ebf2 increased the activity of secreted luciferase. Mutations introduced to the proximal olf-1 site (D1 and M1 groups) increased, whereas mutations of the distal olf-1 site (D2 and M2) decreased the expression of luciferase, compared with that in the WT promoter sequence in parental 293 cells. In 293-ebf2 cells, deletion of the proximal site increased luciferase expression, whereas the other mutations caused no statistically significant changes, although trends similar to those observed in parental 293 cells were observed. *P<0.01 (analysis of variance and Holm-Sidak post-hoc test) vs. groups indicated by joining lines. n=8 experiments/group. WT, wild-type; D, deletion; M, mutation; ebf2, early B-cell factor 2; IFN, interferon; PAR, parental.

Perturbation of olf-1 sites in the minimal Hcrt promoter affects reporter gene expression

The effects of deleting or mutating the two putative olf-1 sites within the minimal Hcrt promoter sequence were then analyzed. The deletions consisted of eliminating a 10-bp fragment spanning the central CCTGG motif of the olf-1 sites. In the mutant promoter constructs, this central motif was replaced with an AAGAA sequence (Fig. 1).

Deletion or mutation of the proximal olf-1 site (D1 and M1 constructs) increased luciferase expression in the 293 cells, whereas the deletion of the distal olf-1 site (D2 construct) induced a marginal decrease in luciferase levels, although without statistical significance. Mutation of this distal site (M2 construct) did not alter luciferase activity, compared with that observed in the cells transfected with the WT construct (Fig. 2A).

Overexpression of ebf2 increases Hcrt-driven reporter gene expression

As the olf-1 sites are putative binding sites for ebf2, the present study analyzed the expression of this transcription factor in 293 cells using RT-qPCR probes. The contribution of the ebf2 transcription factor to Hcrt gene regulation was analyzed by inducing the overexpression of ebf2 in 293 cells through lentiviral transduction of the murine ebf2 cDNA.

The transduced 293-ebf2 cells expressed high mRNA levels of ebf2 (400 copies/1,000 copies of GAPDH mRNA) and the overexpression of ebf2 in the 293 cells increased the luciferase levels driven by the minimal Hcrt-gene promoter by almost 4-fold, compared with the parental 293 cell line (Fig. 2B). In these 293-ebf2 cells, deletion of the proximal olf-1 site (D1 construct) increased luciferase activity by almost 2-fold. Mutation of this proximal site induced an increase in luciferase expression, although this was not statistically significant (Fig. 2B).

Deletion or mutation of the distal olf-1 site (D2 and M2 constructs) did not significantly alter the expression of luciferase, although the luciferase levels tended to be lower, compared with those observed with the WT construct in 293-ebf2 cells (Fig. 2B).

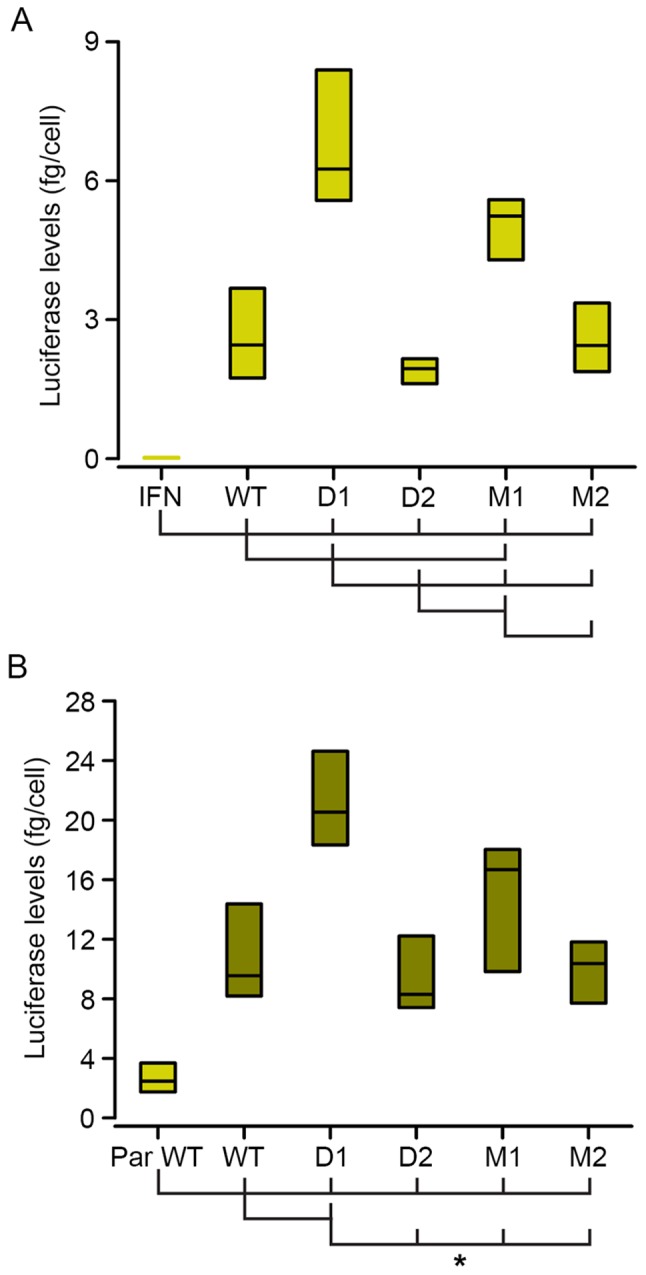

Semi-stable transfections demonstrate the different roles of the distal and proximal olf-1 sites of the minimal Hcrt promoter

In order to determine whether the observed variations in luciferase expression were due to different transfection rates for each construct, semi-stable cells lines were generated, which carried the different variant constructs of the minimal Hcrt-gene promoter, by selecting the transfected cultures under zeocin for 1 month prior to analyzing luciferase expression.

In these semi-stable cells lines, deletion (D1) of the proximal olf-1 site of the Hcrt promoter increased the levels of luciferase activity almost 4-fold, whereas the mutation of this proximal site (M1 construct) increased luciferase expression by 2-fold, compared with those observed with the WT promoter (Fig. 3). Deletion (D2) or mutation (M2) of the distal site decreased luciferase expression by 85 and 80%, respectively, compared with the WT promoter. These results indicated that the distal olf-1 site was a positive regulator of the activity of the minimal Hcrt-gene promoter, as its mutation led to decreased expression. The proximal olf-1 site was a negative regulator of this promoter activity.

Figure 3.

Expression of a luciferase reporter gene is driven by different derivatives of the minimal Hcrt promoter in semi-stable 293-ebf2 cells. Luciferase signals from semi-stable 293-ebf2 cells show the expression of luciferase driven by the different Hcrt promoter sequence derivatives. Mutations introduced to the proximal olf-1 site (D1 and M1) increased luciferase, whereas mutations of the distal olf-1 site (D2 and M2) decreased luciferase, compared with that in the WT promoter sequence. *P<0.01 (analysis of variance and Holm-Sidak post-hoc test) vs. groups indicated by joining lines. n=18 experiments/group. WT, wild-type; D, deletion; M, mutation; ebf2, early B-cell factor 2.

mRNA levels of luciferase correlate with levels of luciferase secreted by the semi-stable Hcrt-promoter derivative cell lines

In order to analyze whether the levels of the secreted luciferase protein were correlated with the levels of transcription, the steady-state levels of mRNA coding for the luciferase reporter were analyzed. This involved assaying two sets of primers and hydrolysis probes, designed to amplify luciferase mRNA transcripts starting at the consensus transcription starting site (TSS) at position +1 of the Hcrt gene or at position +46, which is a sequence identical to the consensus TSS present downstream in this promoter (Fig. 1). If the transcripts start at position +1, the ratio of the qPCR products are expected to approach 1, whereas if position +46 is used as the TSS, the 3′-TSS/5′-TSS ratios are expected to increase.

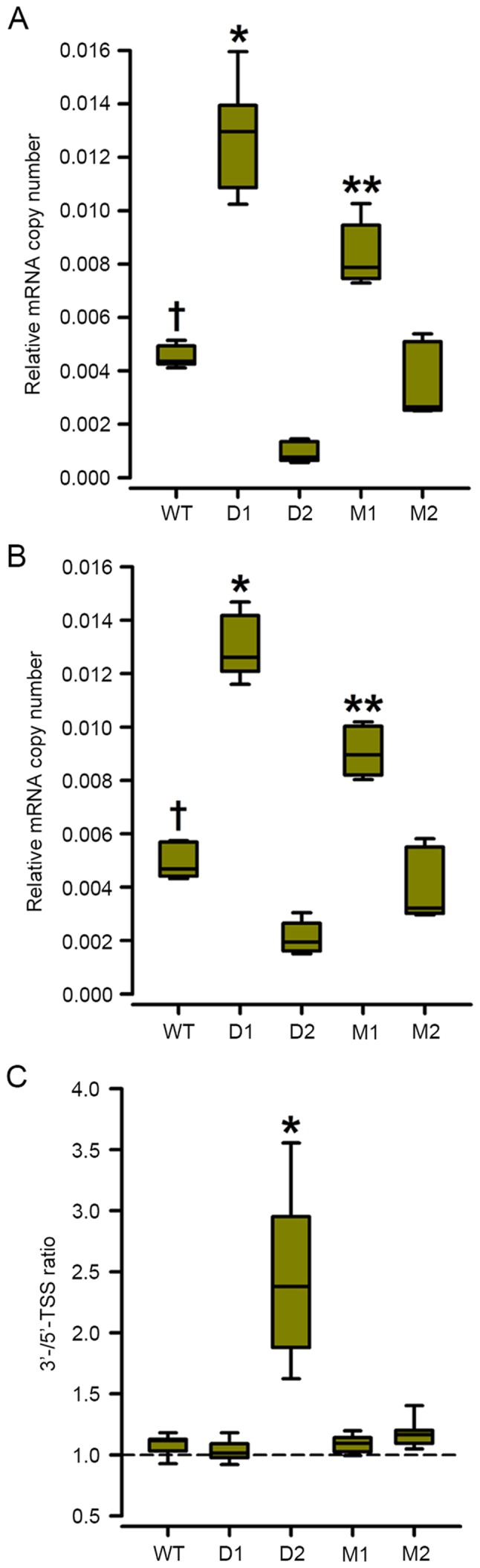

Deletion or mutation of the proximal olf-1 site (D1 and M1 constructs) increased the steady-state levels of luciferase-coding mRNA ~2-fold in the semi-stable 293-ebf2 cells (Fig. 4A and B) and all the transcripts appeared to start at the consensus TSS, as there were no changes in the ratio of the levels of the qPCR products containing the 3′ vs. the 5′ TSS (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Steady-state luciferase mRNA levels correlate with luciferase protein levels in 293-ebf2 semi-stable cell lines. The steady-state levels of mRNA containing either the (A) 5′- or (B) 3′-TSSs of the predicted luciferase constructs correlated with levels of luciferase secreted by the semi-stable 293-ebf2 cell lines. Those cells carrying mutations of the proximal olf-1 site (D1 and M1) showed higher copy numbers of luciferase-coding mRNA, compared with cells carrying the WT, D2 and M2 constructs. (C) Ratios of the levels of luciferase mRNA containing different TSSs showed a shift in the starting position of this gene product, which was induced by the deletion of the distal olf-1 site. *P<0.01 (analysis of variance and Holm-Sidak post-hoc test) vs. all other groups. **P<0.01 vs. WT, D2 and M2 293-ebf2 cells; †P<0.01 vs. D2/293-ebf2 cells. n=9 experiments per group. WT, wild-type; D, deletion; M, mutation; ebf2, early B-cell factor 2; TSS, transcription start site.

By contrast, deletion of the distal olf-1 site (D2 construct) decreased the mRNA levels of luciferase starting the position +1 TSS by ~80%, whereas the mRNA levels starting at the +46 TSS decreased by ~60% (Fig. 4A). The ratio of 3′-TSS-containing/5′-TSS-containing qPCR increased almost 2.3-fold, indicating that deletion of the distal olf-1 site shifted the TSS downstream (Fig. 4C). Mutation of the distal olf-1 site (M2 construct) induced a marginal, non-significant decrease in mRNA levels of luciferase and a shift towards the 3′ TSS (Fig. 4A and B).

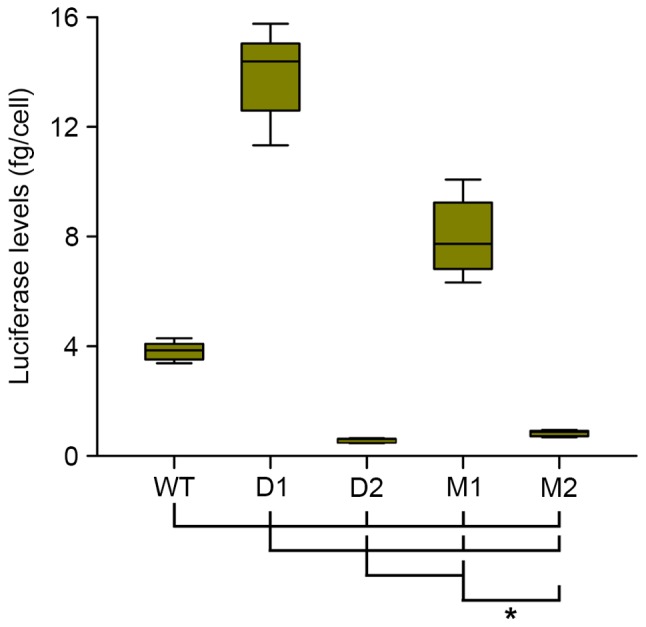

Distal olf-1 sequence of the Hcrt minimal promoter is a binding site for ebf2

The present study also evaluated the capability of ebf2 to bind to the distal olf-1 sequence present in the minimal Hcrt promoter, by performing an EMSA using a biotinylated 50-bp duplex oligonucleotide corresponding to the OE1 element of the Hcrt gene promoter containing this distal olf-1 site (Table I). As shown in Fig. 5A, the mRNA expression of ebf2 was not detected in the 293 cells, therefore, the contribution of ebf2 was analyzed by inducing the overexpression of ebf2 in 293 cells through lentiviral transduction of the murine ebf2 cDNA. Nuclear protein extracts from the 293-ebf2 cells, but not from the parental 293 cells, induced a shift in the mobility of the duplex (Fig. 5B). This shifted band disappeared when the EMSA reaction included a 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide (Fig. 5B, lane 3).

Figure 5.

EMSA shows the interaction of murine ebf2 with an oligonucleotide containing the distal olf-1 site of the Hcrt promoter. (A) In P 293 cells, the mRNA expression of endogenous ebf2 was not detected by species-specific quantitative polymerase chain reaction primers and hydrolysis probes (left bar). Lentiviral transduction of the murine ebf2 cDNA sequence induced high mRNA expression levels of this transcription factor in 293 cells (ebf2; *P<0.01 vs. P 293 cells). n=6 experiments per group. (B) A biotinylated oligonucleotide containing the sequence of the distal olf-1 site of the minimal Hcrt gene promoter was artificially synthesized. This probe was incubated with nuclear extracts from parental 293 cells (lane 1) or 293-ebf2 cells (lane 2), and the latter extract showed a shift in mobility of the olf-1 oligonucleotide (arrow in middle of lane 2). This shift was no longer apparent when a 1,000-fold excess of unlabeled oligonucleotide competed with the interaction between the probe and the nuclear extract (lane 3). ebf2, early B-cell factor 2; P, parental; N.D., not detected.

Discussion

Understanding the mechanisms regulating the expression of orexin is key to generating novel therapeutic approaches for disorders of motivation, including feeding and addictive behavior and sleep behavior, including narcolepsy and insomnia. The levels of orexin in the brain vary during the day according to the physical activity of animals. However, whether these variations are due to changes in the activity of the orexin-secreting neurons or to changes in orexin biosynthesis, either at the transcriptional or translational level, remain to be fully elucidated (3,27–32). These regulatory mechanisms are also involved in the developmental determination of the orexinergic phenotype of hypothalamic neurons, and the in vitro generation of such neurons may lead to cell-based therapies for orexin replacement.

The promoter region of the Hcrt gene is a key element in regulating the expression of orexin in the target neural population within the hypothalamus. This region contains different control sites, which specify and restrict the expression of prepro-orexin within the LHA, including orexin regulatory elements 1 and 2 (OE1 and OE2). The OE1 site lies proximal to the putative transcriptional start site of Hcrt mRNA and it has been suggested that the OE1 site prevents the gene expression of Hcrt outside the LHA, as constructs containing a 400-bp upstream fragment of the Hcrt gene driving a nuclear β-galactosidase reporter gene were poorly expressed in the brains of transgenic mice (16). It is suggested that this restrictive role is mediated by nuclear receptor response elements (NurREs), which lie in the close upstream vicinity of the OE1 element (12).

The inhibitory activity of the OE1 element has also been suggested as the cause of poor expression of reporter genes driven by the Hcrt promoter in cell lines in vitro (12,17,19,33,34). The results of the present study showed that a minimal fragment of the mouse Hcrt gene, containing just up to the OE1 element, was able to drive the expression of a secreted luciferase reporter gene, to levels ~100-fold higher than those driven by the minimal IFN-β promoter (Fig. 2) in human embryonic 293 cells.

The differences in the expression between the constructs in the present study and those of other groups can be attributed to several factors. By using artificial gene synthesis, the present study limited the length of the minimal promoter to 17 bp upstream of the OE1 sequence, thus avoiding the inclusion of NurREs described previously (12,17). The constructs used in the present study preserved the context of the transcription and translation start sites of the Hcrt gene (Fig. 1), and the distance between the transcription start site and the initial AUG codon of the Hcrt transcript. Constructs generated in other studies, driving the expression of reporter genes by using a longer Hcrt gene promoter, exchange the context of the Hcrt transcript with those of the reporter genes (12,16).

Overexpression of the transcription factor ebf2 in the 293 cells increased the Hcrt-driven luciferase expression by almost 4-fold (Fig. 2B). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a transcription factor upregulating Hcrt promoter-driven gene expression in 293 cells. Other transcription factors, including Foxa2 and Lim-homeobox 9 (Lhx9), have been suggested to increase in vivo expression at the Hcrt locus (19,33) and it has been shown that Foxa2 increases Hcrt-driven reporter gene expression in a hepatocyte cell line (19).

In our previous study, it was demonstrated that the loss of ebf2 activity in knockout mice led to narcoleptic traits and a marked decrease in orexinergic neuron numbers (20). The findings of the present study suggested that this effect is attributed to direct regulation at the level of the Hcrt locus (Fig. 5B). In addition, ebf2 may contribute to the cell-type specification process of the orexinergic phenotype in the LHA through this direct effect and indirect effects on other regulators of the expression of Hcrt.

It may be that ebf2 is a key regulator of orexinergic neuron development, joining a network of transcription factors, including Lhx9 (33,34) and sonic hedgehog (35), which may be involved in establishing the mature phenotype of the orexinergic population in the LHA. The order in which these transcription factors are involved during development remains to be elucidated.

The analysis of the proximal Hcrt gene promoter region in the present study revealed novel features of its regulatory elements. Mutation of a 10-bp segment with a putative olf-1-like sequence 7 bp downstream of the TATAA box of the minimal Hcrt promoter, either by deletion (D1 construct) or nucleotide substitution (M1 construct), increased the mRNA levels of the reporter gene (Figs. 2 and 3) and luciferase (Fig. 4) by almost 3-fold. Taken together, these results suggested that the olf-1-like sequence downstream of the TATAA box was a negative element, which controlled the expression of orexin through downregulation.

Perturbations of the distal olf-1-like site at position-236 (D2 and M2 constructs; Fig. 1), which lies within the OE-1 element, decreased reporter gene expression at the enzymatic and mRNA levels, particularly in the semi-stable 293-ebf2 derivative cell lines (Figs. 3 and 4). The OE-1 element has been previously reported as a restrictive element of the expression of Hcrt, as deletions within the OE-1 sequence prevent the expression of a transgenic reporter gene in LHA orexinergic neurons, and direct expression to a limited small population of hypothalamic neurons populations outside the LHA (12,16). Taken together, the previous observations and those of the present study showed that integrity of the OE-1 element may be necessary to drive high levels of expression by the Hcrt gene promoter.

The mutations introduced to the distal olf-1 site appeared to shift the TSS of the reporter gene mRNA to a downstream position at +46, as the level of mRNA containing this +46-sequence increased above that containing the TSS sequence at +1 in the semi-stable 293-ebf2 cells carrying the D2 and M2 constructs, particularly when the distal olf-1 site was deleted (Fig. 4B). This shift appeared to lead to lower rates of translation of luciferase mRNA, as the enzymatic activity levels in these semi-stable cells were lower than the corresponding mRNA levels, compared with those in cells carrying the WT construct (Figs. 3 and 4).

The distal olf-1 sequence was identified as a binding site for ebf2 as nuclear extracts from 293-ebf2 cells, but not from parental 293 cells, induced a shift in electrophoretic mobility, which was competed by an unlabeled oligonucleotide contacting this olf-1 sequence (Fig. 5B). This result suggested that ebf2 was a direct regulator of Hcrt-gene promoter driven expression in vitro, however, the relevance of this effect during development or the adult stage in vivo remains to be elucidated.

The data obtained in the present study demonstrated that a minimal sequence derived from the murine Hcrt gene was able to drive high levels of expression in a heterologous system and that ebf2 is a transcription factor, which increased the activity of this Hcrt gene minimal promoter in vitro. The identification of this minimal promoter may lead to improved vectors for gene therapy, where the expression of orexin is required, and the identification of ebf2 as a direct regulator of the expression of orexin may lead to the development of orexin-expressing cells for cell therapies in the treatment of narcolepsy.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Mexico (grant no. 220342 to R. Vidaltamayo and grant no. 220006 to V. Zomosa-Signoret) and Vicerrectoría Académica-Universidad de Monterrey (grant nos. 14011, 15027 and 17559 to Román Vidaltamayo). Authors would like to thank Mr. Alejandro Trejo and Mr. Alejandro Treviño for their technical assistance.

References

- 1.de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, II, et al. The hypocretins: Hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 1998; pp. 322–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richarson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: A family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Routh VH, Hao L, Santiago AM, Sheng Z, Zhou C. Hypothalamic glucose sensing: Making ends meet. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:236. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsujino N, Sakurai T. Role of orexin in modulating arousal, feeding, and motivation. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:28. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuñez A, Rodrigo-Angulo ML, Andrés ID, Garzón M. Hypocretin/orexin neuropeptides: Participation in the control of sleep-wakefulness cycle and energy homeostasis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2009;7:50–59. doi: 10.2174/157015909787602797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohno K, Sakurai T. Orexin neuronal circuitry: Role in the regulation of sleep and wakefulness. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:70–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuki T, Sakurai T. Orexins and orexin receptors: From molecules to integrative physiology. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2008;46:27–55. doi: 10.1007/400_2007_047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai XJ, Widdowson PS, Harrold J, Wilson S, Buckingham RE, Arch JR, Tadayyon M, Clapham JC, Wilding J, Williams G. Hypothalamic orexin expression: Modulation by blood glucose and feeding. Diabetes. 1999;48:2132–2137. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.11.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffond B, Risold PY, Jacquemard C, Colard C, Fellmann D. Insulin-induced hypoglycemia increases preprohypocretin (orexin) mRNA in the rat lateral hypothalamic area. Neurosci Lett. 1999;262:77–80. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00976-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner D, Salin-Pascual R, Greco MA, Shiromani PJ. Distribution of hypocretin-containing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus and C-fos-immunoreactive neurons in the VLPO. Sleep Res Online. 2000;3:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakurai T, Nagata R, Yamanaka A, Kawamura H, Tsujino N, Muraki Y, Kageyama H, Kunita S, Takahashi S, Goto K, et al. Input of orexin/hypocretin neurons revealed by a genetically encoded tracer in mice. Neuron. 2005;46:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka S, Kodama T, Nonaka T, Toyoda H, Arai M, Fukazawa M, Honda Y, Honda M, Mignot E. Transcriptional regulation of the hypocretin/orexin gene by NR6A1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;403:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakurai T, Moriguchi T, Furuya K, Kajiwara N, Nakamura T, Yanagisawa M, Goto K. Structure and function of human prepro-orexin gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17771–17776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunningham F, Amode MR, Barrell D, Beal K, Billis K, Brent S, Carvalho-Silva D, Clapham P, Coates G, Fitzgerald S, et al. Ensembl 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D662–D669. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waleh NS, Apte-Deshpande A, Terao A, Ding J, Kilduff TS. Modulation of the promoter region of prepro-hypocretin by alpha-interferon. Gene. 2001;262:123–128. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00544-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moriguchi T, Sakurai T, Takahashi S, Goto K, Yamamoto M. The human prepro-orexin gene regulatory region that activates gene expression in the lateral region and represses it in the medial regions of the hypothalamus. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16985–16992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka S. Transcriptional regulation of the hypocretin/orexin gene. Vitam Horm. 2012;89:75–90. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394623-2.00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honda M, Eriksson KS, Zhang S, Tanaka S, Lin L, Salehi A, Hesla PE, Maehlen J, Gaus SE, Yanagisawa M, et al. IGFBP3 colocalizes with and regulates hypocretin (orexin) PLoS One. 2009;4:e4254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva JP, von Meyenn F, Howell J, Thorens B, Wolfrum C, Stoffel M. Regulation of adaptive behaviour during fasting by hypothalamic Foxa2. Nature. 2009;462:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature08589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De La Herrán-Arita AK, Zomosa-Signoret VC, Millán-Aldaco DA, Palomero-Rivero M, Guerra-Crespo M, Drucker-Colín R, Vidaltamayo R. Aspects of the narcolepsy-cataplexy syndrome in O/E3-null mutant mice. Neuroscience. 2011;183:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang SS, Lewcock JW, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P, Reed RR. Genetic disruptions of O/E2 and O/E3 genes reveal involvement in olfactory receptor neuron projection. Development. 2004;131:1377–1388. doi: 10.1242/dev.01009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Dominguez M, Poquet C, Garel S, Charnay P. Ebf gene function is required for coupling neuronal differentiation and cell cycle exit. Development. 2003;130:6013–6025. doi: 10.1242/dev.00840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croci L, Chung SH, Masserdotti G, Gianola S, Bizzoca A, Gennarini G, Corradi A, Rossi F, Hawkes R, Consalez GG. A key role for the HLH transcription factor EBF2COE2,O/E-3 in Purkinje neuron migration and cerebellar cortical topography. Development. 2006;133:2719–2729. doi: 10.1242/dev.02437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chuang SM, Wang Y, Wang Q, Liu KM, Shen Q. Ebf2 marks early cortical neurogenesis and regulates the generation of cajal-retzius neurons in the developing cerebral cortex. Dev Neurosci. 2011;33:479–493. doi: 10.1159/000330582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roby YA, Bushey MA, Cheng LE, Kulaga HM, Lee SJ, Reed RR. Zfp423/OAZ mutation reveals the importance of Olf/EBF transcription activity in olfactory neuronal maturation. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13679–13688. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6190-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burt J, Alberto CO, Parsons MP, Hirasawa M. Local network regulation of orexin neurons in the lateral hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R572–R580. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00674.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanno S, Terao A, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Kimura K. Hypothalamic prepro-orexin mRNA level is inversely correlated to the non-rapid eye movement sleep level in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2013;7:e251–e257. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arafat AM, Kaczmarek P, Skrzypski M, Pruszyńska-Oszmałek E, Kołodziejski P, Adamidou A, Ruhla S, Szczepankiewicz D, Sassek M, Billert M, et al. Glucagon regulates orexin A secretion in humans and rodents. Diabetologia. 2014;57:2108–2116. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwasa T, Matsuzaki T, Munkhzaya M, Tungalagsuvd A, Kuwahara A, Yasui T, Irahara M. Developmental changes in the hypothalamic mRNA levels of prepro-orexin and orexin receptors and their sensitivity to fasting in male and female rats. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2015;46:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Justinussen JL, Holm A, Kornum BR. An optimized method for measuring hypocretin-1 peptide in the mouse brain reveals differential circadian regulation of hypocretin-1 levels rostral and caudal to the hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2015;310:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Y, Leri F, Cummins E, Kreek MJ. Individual differences in gene expression of vasopressin, D2 receptor, POMC and orexin: Vulnerability to relapse to heroin-seeking in rats. Physiol Behav. 2015;139:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalal J, Roh JH, Maloney SE, Akuffo A, Shah S, Yuan H, Wamsley B, Jones WB, de Guzman Strong C, Gray PA, et al. Translational profiling of hypocretin neurons identifies candidate molecules for sleep regulation. Genes Dev. 2013;27:565–578. doi: 10.1101/gad.207654.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J, Merkle FT, Gandhi AV, Gagnon JA, Woods IG, Chiu CN, Shimogori T, Schier AF, Prober DA. Evolutionarily conserved regulation of hypocretin neuron specification by Lhx9. Development. 2015;142:1113–1124. doi: 10.1242/dev.117424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szabó NE, Zhao T, Cankaya M, Theil T, Zhou X, Alvarez-Bolado G. Role of neuroepithelial Sonic hedgehog in hypothalamic patterning. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6989–7002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1089-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]