Abstract

Contemporary research has focused on the function of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in carcinogenesis. However, the involvement of the lncRNA, steroid receptor RNA activator (SRA), in cervical carcinogenesis remains to be elucidated. In the present study, we investigated the bio-functional consequences of lncRNA SRA knockdown in vitro. To verify the role of lncRNA SRA in cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, lncRNA RNA interference was utilized to knock down lncRNA SRA expression in cervical cancer cell lines, resulting in our discovery that lncRNA SRA knockdown inhibited cell proliferation, cell migration and tumor invasion in the cervical cancer cell lines. Additionally, in vitro experiments using the lncRNA SRA-knockdown cervical cancer cell lines revealed that lncRNA SRA is a strong inducer and modulator of the expression of genes related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the NOTCH signaling pathway. In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that lncRNA SRA is highly correlated with cancer progression and cervical cancer cell proliferation and migration. Furthermore, these results indicate that lncRNA SRA may be a potential therapeutic target and prognostic marker for cervical malignancy.

Keywords: steroid receptor RNA activator, SRA, long non-coding RNA, invasion, migration, cervical cancer

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women worldwide (1). Widespread employment of screening programs has reduced the incidence and mortality associated with this cancer. However, it remains a major public health issue, particularly concerning advanced cases (1). Accordingly, recent research has focused on identifying tumor-specific markers capable of predicting the biological behavior of cervical cancers with respect to cell motility and invasion (2).

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are potential key factors influencing gene regulation and cancer cell phenotypes (3,4). Recently, more than 3,000 human long intervening coding RNAs and most long ncRNAs (lncRNAs) have been found to correlate the activity associated with DNA-binding proteins, including chromatin-modifying complexes (5) that epigenetically modify the expression of various genes (6). Additionally, transcription of lncRNAs modulates gene expression in response to external oncogenic stimuli or DNA damage (7).

Human lncRNA, steroid receptor RNA activator (SRA), was shown to co-activate several human sex hormone receptors and was found to be highly associated with several types of cancers including ovarian and breast cancer (8–11). In addition, lncRNA SRA functionally interacts with several proteins, including nuclear receptors, such as the retinoic acid receptor, as well as proteins involved in myogenic differentiation (12,13). Although lncRNA SRA is also correlated with the progression of other malignancies, its role in cervical cancer has not yet been fully elucidated.

The present study investigated the expression and molecular function of SRA in cervical cancer cell lines and elucidated the role of SRA in the metastatic progression of cervical cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Squamous cell cervical carcinoma (SiHa) cells and epidermoid cell cervical carcinoma (CaSki; originally derived from a small-bowel mesentery metastasis) cells and human cervical cancer cell lines [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) Manassas, VA, USA], were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Only cells that had been passaged <20 times were utilized in the experiments.

Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

We extracted total RNA using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturers instructions. Total RNA (2 µg) was reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA using a reverse transcription reagent kit (Invitrogen). The cDNA template was amplified by qRT-PCR using the SYBR-Green Real-Time PCR kit (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) on an ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). We used U6 as the internal standard for all quantifications. We analyzed the relative gene expression using the 2−ΔΔCt method, and the results are expressed as the extent of change relative to control values. All qRT-PCR experiments were repeated at least three times. Primers used for the PCR reactions are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Primer sequences used in the present study.

| Primer sequence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Forward (5–3) | Reverse (5–3) | Product size (bp) |

| SRA | CTCCCTTCTTACCACCACCA | TGCAGATACACAGGGAGCAG | 217 |

| MMP-9 | CGCTACCACCTCGAACTTTG | GCCATTCACGTCGTCCTTAT | 196 |

| MMP-2 | GGATGATGCCTTTGCTCG | ATAGGATGTGCCCTGGAA | 487 |

| VEGF | TTGCTGCTCTACCTCCAC | AAATGCTTTCTCCGCTCT | 419 |

| E-cadherin | ATTCTGATTCTGCTGCTCTTG | AGTAGTCATAGTCCTGGTCCT | 421 |

| β-catenin | TGCAGTTCGCCTTCACTATG | ACTAGTCGTGGAATGGCACC | 162 |

| N-cadherin | CCCAAGACAAAGAGACCCAG | GCCACTGTGCTTACTGAATTG | 140 |

| Vimentin | TGGATTCACTCCCTCTGGTT | GGTCATCGTGATGCTGAGAA | 111 |

| Snail | GAGGCGGTGGCAGACTAG | GACACATCGGTCAGACCAG | 178 |

| NOTCH1 | GCCGCCTTTGTGCTTCTGTTC | CCGGTGGTCTGTCTGGTCGTC | 300 |

| HES1 | TCAACACGACACCGGATAAA | TCAGCTGGCTCAGACTTTCA | 111 |

| P300 | GACCCTCAGCTTTTAGGAATCC | TGCCGTAGCAACACAGTGTCT | 301 |

SRA, steroid receptor RNA activator; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

We obtained siRNA for SRA lncRNA and negative-control siRNA (siNC) from Genolution Pharmaceuticals (Seoul, Korea). Cells (5×104 cells/well) were seeded into 6-well plates and transfected with 10 nM siRNA in phosphate-buffered saline using the G-Fectin kit (Genolution Pharmaceuticals) according to the manufacturers instructions. The siRNA-transfected cells were used in the in vitro assays 48 h after transfection. The target sequence for the siSRA was, 5′-CTCCCTTCTTACCACCACCA-3′. Experiments were repeated at least three times.

Plasmid constructs and generation of stable cell lines

Full-length human SRA-transcript cDNA was amplified by PCR and inserted into the pLenti6/V5-D-TOPO vector using the ViraPower lentiviral expression system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers instructions. We then transfected the plasmid into 293FT cells for packaging, with the resultant lentivirus used to infect the desired cell lines. Stably SRA-transfected cells were selected in medium containing blasticidin (Invitrogen).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) was utilized to evaluate cell proliferation. Cells (2×103 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well flat-bottomed plates containing 100 µl of complete medium per well. The cells were incubated overnight to allow for cell attachment and recovery, and subsequently transfected with siNC or siSRA for 24, 48, 72 or 96 h. An aliquot of 10 µl of CCK-8 solution was supplemented into each well, followed by incubation for 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm to estimate the number of viable cells in each well. The assay was performed in triplicate.

Matrigel invasion assay

We performed a Matrigel invasion assay using the BD Biocoat Matrigel invasion chamber (pore size, 8-µm; 24-wells; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) according to the manufacturers protocol. Cells (5×104) were seeded in the upper chamber, which contained serum-free medium, and complete medium was added to the lower chamber. The Matrigel-invasion chamber was incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 48 h. Non-invading cells were removed from the upper chamber using cotton-tipped swabs. Cells that had invaded through the pores onto the lower side of the filter were stained (Diff-Quik; Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) and counted using a hemocytometer. The assay was repeated at least three times.

Wound-healing migration assay

We evaluated cell migration using a wound-healing assay. Approximately 5×105 cells were seeded into 6-well culture plates containing serum-enriched medium and allowed to grow to 90% confluence in complete medium. The serum-containing medium was eliminated, and cells were serum-starved for 24 h. When the cells reached 100% confluence, an artificial homogenous wound was made by scratching the monolayer using a sterile 200-µl pipette tip. Following the scratching, cells were washed with serum-free medium. Images of cells migrating into the wound were captured at 0, 24 and 48 h using a microscope. Three independent experiments were performed in triplicate.

Western blot analysis

We used radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer to extract proteins, and a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to measure protein concentration. Proteins were boiled with 2X sample buffer, subsequently resolved on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, and transferred electrophoretically to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% non-fat dried milk in 1X Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (pH 7.6) at room temperature for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight under continual agitation. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-human vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (1:500), rabbit anti-human matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 (1:500) (both from Abcam, Cambridge, UK, USA), rabbit anti-human MMP-9 (1:1,000), rabbit anti-human E-cadherin (1:1,000), rabbit anti-human β-catenin (1:1,000) (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), mouse anti-human vimentin (1:1,000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), mouse anti-human Snail (1:1,000), rabbit anti-human SOX-2 (1:1,000), rabbit anti-human Nanog (1:1,000), rabbit anti-human Oct4 (1:1,000) (all from Cell Signaling Technology), and mouse anti-human β-actin (1:5,000; Sigma-Aldrich). We visualized the proteins using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Little Chalfont, UK), and band intensities were quantified using a luminescent image analyzer (LAS-4000 Mini; Fujifilm, Uppsala, Sweden).

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS version 23 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to validate standard normal-distributional assumptions. Statistical significance was determined using the Fisher's exact-test, Pearson's Chi-square test and Student's t-test. Mean differences were considered significant at P<0.05. Results are presented as the means ± standard deviation.

Results

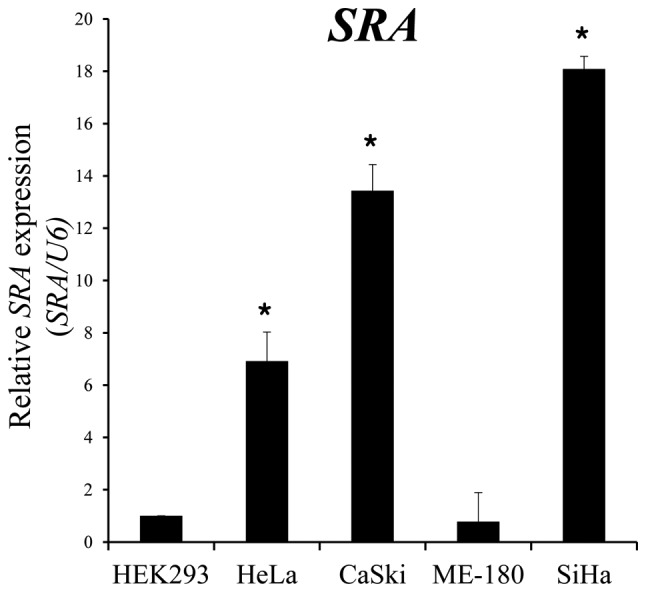

SRA expression is elevated in cervical cancer cells

We performed qRT-PCR to estimate the expression levels of SRA in five different cell lines, one of which was derived from human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293), whereas the other four were derived from human cervical cancers. We observed that SRA expression levels were significantly higher in epithelioid cervical carcinoma (HeLa), CaSki and SiHa cells as compared with levels observed in epidermoid cervical carcinoma cells (ME-180) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

SRA expression in various cell lines. SRA lncRNA expression was evaluated by qRT-PCR, with U6 as an internal control. *P<0.05 vs. non-tumor control. lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SRA, steroid receptor RNA activator.

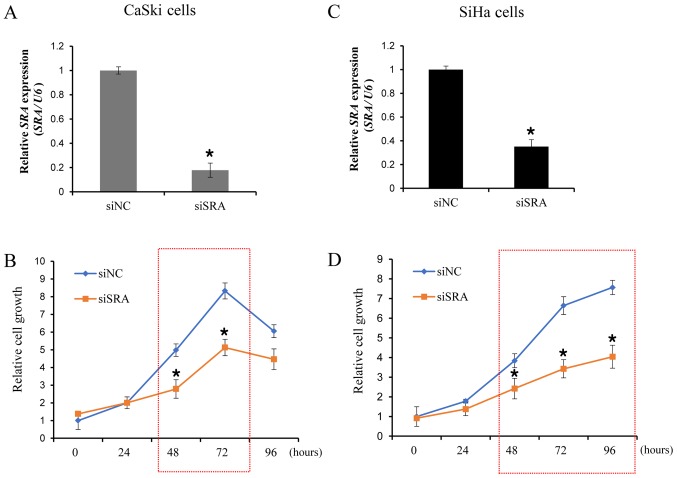

Knockdown of SRA decreases cell proliferation in cervical cancer cells

To examine the functional role of SRA in cervical cancer cells, siRNA was utilized to downregulate SRA expression in the CaSki and SiHa cells, which showed significantly higher levels of SRA expression. We evaluated the knockdown efficiency of siSRAs, and verified that siSRA transfection was more efficient in silencing SRA as compared with siNC (Fig. 2A and C). We then performed a CCK-8 assay to determine the effect of SRA knockdown on cell proliferation. Our results showed that siRNA-mediated knockdown of SRA in CaSki and SiHa cells substantially decreased cell proliferation (Fig. 2B and D). These findings indicated that SRA is involved in the proliferation of cervical cancer cells.

Figure 2.

SRA knockdown inhibits the proliferation of cervical cancer cells. (A and C) Cells were transfected with SRA-specific siRNA (siSRA) and negative-control siRNA (siNC), and knockdown efficiency was determined by qRT-PCR analysis in CaSki and SiHa cells. (B and D) The proliferation capacity of cervical cancer cells transfected with siSRA and siNC was determined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. Bars indicate means ± standard deviation of three independent experiments; *P<0.05 vs. siNC. CaSki, epidermoid cell cervical carcinoma cells; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SiHa, squamous cell cervical carcinoma cells; SRA, steroid receptor RNA activator.

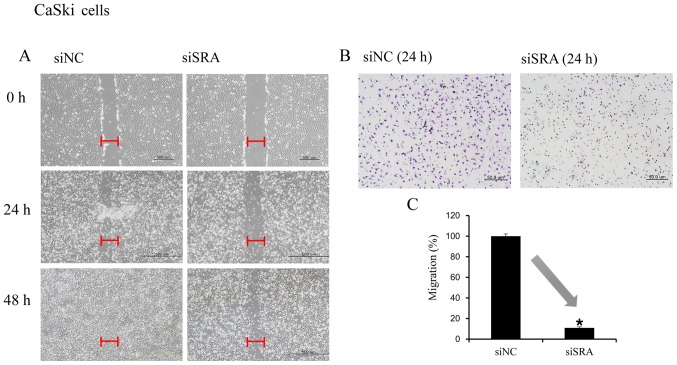

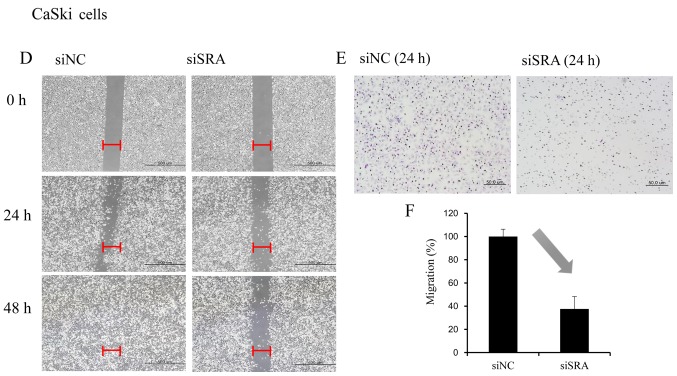

SRA knockdown inhibits cervical cancer cell migration and invasion

Wound-healing and Matrigel-invasion assays were performed to determine whether SRA plays a role in cervical cancer cell migration and invasion. In the wound-healing assay, siRNA-mediated knockdown of SRA inhibited cell migration in the CaSki and SiHa cells (Fig. 3A and D). Moreover, SRA-knockdown inhibited cell invasion in the CaSki and SiHa cells according to the results of the Matrigel-invasion assay (Fig. 3B and E). The extent of inhibition upon SRA knockdown was quantified by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3C and F).

Figure 3.

SRA lncRNA promotes cell migration and invasion. (A and D) Wound-healing assay was used to determine migration ability of the siSRA-transfected CaSki and SiHa cells (magnification, ×200). (B and E) Matrigel-invasion assay was used to determine invasion after 24 h in siSRA-transfected CaSki and SiHa cells. Each assay was performed in triplicate. Data are presented as means ± standard deviation. (C and F) siRNA-mediated knockdown of SRA in CaSki and SiHa cells analyzed using qRT-PCR; *P<0.05 vs. control. CaSki, epidermoid cell cervical carcinoma cells; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SiHa, squamous cell cervical carcinoma cells; siSRA, SRA-specific siRNA; SRA, steroid receptor RNA activator.

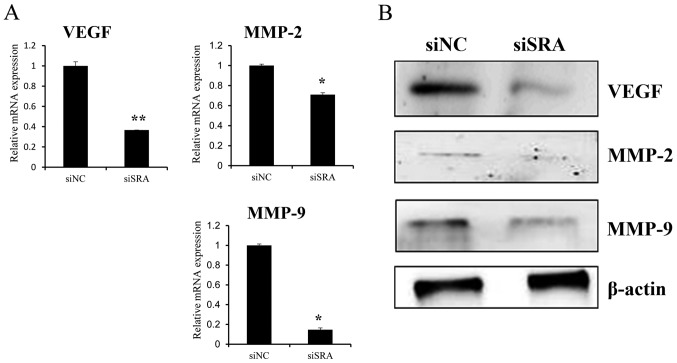

SRA knockdown inhibits MMP-9, MMP-2 and VEGF expression in cervical cancer cells

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effect of SRA knockdown on cell migration and invasion, we explored the relationship between SRA expression and MMP-2, MMP-9 and VEGF expression. We observed that siSRA treatment decreased levels of MMP-2, MMP-9 and VEGF mRNA in the CaSki cells (Fig. 4A) as well as MMP-2, MMP-9 and VEGF protein levels (Fig. 4B). These findings indicated that SRA promoted cervical cancer cell migration and invasion via upregulation of MMP-9, MMP-2 and VEGF expression.

Figure 4.

SRA knockdown decreases MMP-9, MMP-2 and VEGF expression in cervical cancer cells. (A) VEGF, MMP-2 and MMP-9 mRNA expression levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. (B) Protein lysates were obtained from siSRA- and siNC-transfected CaSki cells 48-h post-transfection. VEGF, MMP-2, and MMP-9 protein levels were analyzed by western blotting; *P<0.05 vs. siNC. MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; siNC, negative-control siRNA; siSRA, SRA-specific siRNA; SRA, steroid receptor RNA activator; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

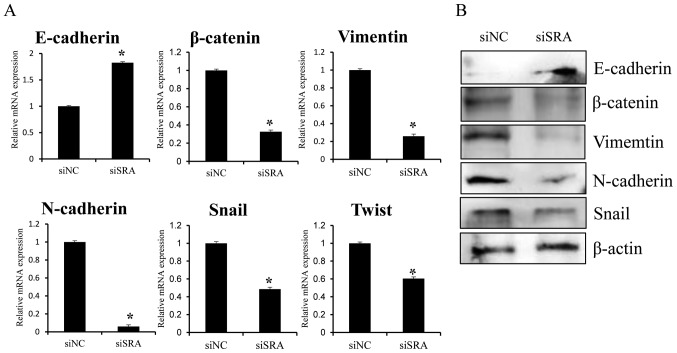

SRA knockdown downregulates expression of genes related to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and the NOTCH-signaling pathway in cervical cancer cells

Since EMT is crucial to cell migration and invasion, we examined whether SRA is required for EMT. EMT was monitored using qRT-PCR and western blotting following siRNA-mediated knockdown of SRA in CaSki cells. SRA knockdown resulted in increased E-cadherin expression and decreased β-catenin and vimentin expression (Fig. 5A and B). Additionally, the EMT-mediating transcription factor Snail and Twist were downregulated in the siSRA-transfected cells relative to levels observed in the siNC-transfected cells (Fig. 5A and B). These results suggested that SRA may be involved in the dysregulation of EMT-related genes in cervical cancer cells, thereby promoting migration and invasion.

Figure 5.

Effect of SRA knockdown on EMT-related genes in CaSki cells. CaSki cells were transfected with siSRA and siNC for 48 h. E-cadherin, β-catenin, vimentin, N-cadherin, Snail and Twist mRNA expression and protein levels were analyzed by (A) qRT-PCR and (B) western blotting, respectively; *P<0.05 vs. siNC. CaSki, epidermoid cell cervical carcinoma cells; EMT, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; siNC, negative-control siRNA; siSRA, SRA-specific siRNA; SRA, steroid receptor RNA activator.

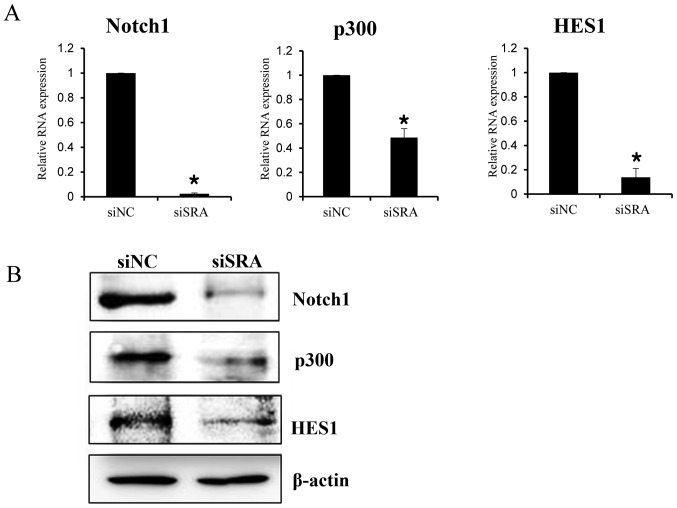

To elucidate the mechanism by which SRA promotes a malignant phenotype in cervical cancer cells, we assessed the status of important signaling cascades controlled by NOTCH in the SRA-knockdown cells. SRA knockdown in the CaSki cells resulted in downregulation of NOTCH1, HES1 and p300 expression [both mRNA (Fig. 6A) and protein (Fig. 6B)]. These data indicated that SRA promoted tumor growth in vitro via the EMT and NOTCH signaling pathways.

Figure 6.

SRA regulates the NOTCH signaling pathway. (A) NOTCH1, p300 and HES1 mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR in siSRA- and siNC-transfected CaSki cells. Each assay was performed in triplicate. Data are presented as means ± standard deviation; *P<0.05 vs. control. (B) Protein lysates were obtained from siSRA- and siNC-transfected CaSki cells. NOTCH1, p300 and HES1 protein levels were analyzed using western blotting. CaSki, epidermoid cell cervical carcinoma cells; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; siNC, negative-control siRNA; siSRA, SRA-specific siRNA; SRA, steroid receptor RNA activator.

Discussion

lncRNAs are transcripts of >200 nucleotides lacking protein-coding capability (7). Numerous lncRNAs are capped, spliced and polyadenylated similar to their protein-coding counterparts and exhibit tissue-specific expression patterns (14). Furthermore, lncRNAs are essential for the regulation of chromatin structure, gene expression and translational control (15). The mounting list of functionally characterized lncRNAs implies that these transcripts are critical to various physiological processes (16). Therefore, these findings suggest that modified lncRNA expression may affect cancer development and progression (17). However, little is known concerning the regulatory roles of lncRNAs and their relevance to malignant diseases.

Recently, lncRNAs have become the focus of intense research due to their critical roles in malignant processes, including tumorigenesis, drug resistance and metastasis (18–20). The present study explored the molecular function of SRA expression in cervical cancer cell lines. Our findings showed that downregulated SRA expression was correlated with decreased cell growth, migration and invasion in cervical cancer cells. This effect of SRA on tumor progression may be mediated by genes involved in cell migration, invasion, EMT and the NOTCH signaling pathway, as well as genes that encode VEGF, MMP-9, MMP-2, E-cadherin, β-catenin, vimentin, Snail, NOTCH1, p300 and HES1. Our findings suggested that SRA could potentially represent a novel biomarker and therapeutic target for cervical cancer.

We discovered that knockout of lncRNA SRA expression decreased cervical cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Specifically, the expression levels of MMP-2, MMP-9 and VEGF were significantly lower in cells with siRNA-mediated SRA knockdown. MMP-2 and MMP-9 degrade basement-membrane collagen at the site of local invasion, thereby promoting tumor-cell invasion and metastasis, which in turn leads to decreased survival rates in various types of cancers (21,22). Moreover, tumor angiogenesis plays a decisive role in tumor growth, invasion and metastasis (23), and the angiogenic factor, VEGF, a major target of many anticancer medications, plays a pivotal role in tumor angiogenesis and increases the ability of malignant cells to migrate and invade Matrigel membranes (24). Our findings suggested that SRA stimulated oncogenic activity in cervical cancer cells by promoting aggressive and metastatic characteristics via upregulating MMP-2, MMP-9 and VEGF expression.

We found that knockout of lncRNA SRA in cervical cancer cells reduced cell migration and invasion, possibly by preventing EMT induction. We analyzed the following EMT-related genes in the present study: E-cadherin, β-catenin, vimentin, N-cadherin, Snail and Twist. EMT is a well-characterized process by which epithelial cells lose their cell polarity and cell-to-cell adhesion and acquire migratory and invasive properties to become mesenchymal stem cells (25), processes that occur during metastasis in many carcinomas (25). Loss of E-cadherin is considered a crucial event in EMT, whereas N-cadherin promotes transendothelial migration, which causes diminished intercellular connection between two adjacent endothelial, thereby allowing cancer cells to slip through (26). Additionally, β-catenin weakens cell-to-cell adhesion between epithelial cells, and promotes a more mobile and loosely associated mesenchymal phenotype (27). Furthermore, enhanced expression of transcription factors, such as Snail and Twist, is associated with loss of intercellular adhesion (28), and vimentin constitutes a major component of the cytoskeleton in mesenchymal cells, with its upregulation promoting EMT induction (29).

In the present study, we also investigated whether the NOTCH signaling pathway was compromised upon SRA knockdown. A clear relationship was detected between decreased levels of NOTCH1, HES1 and p300 proteins and SRA knockdown in CaSki cells. The NOTCH signaling pathway represents a highly conserved cell-signaling mechanism (30) that contributes to tumor progression, including invasion, metastasis, EMT and angiogenesis (31,32). NOTCH1 is a regulatory transmembrane receptor that plays a crucial developmental role in cell-fate determination and pattern formation (30). Several studies reported that NOTCH1 induces anoikis resistance, inhibits p53 activity, upregulates Myc expression, and abrogates the growth-inhibitory effects of TGF-β in cervical cancer cells (33–35). Additionally, HES1 influences the maintenance of stem and progenitor cells as a member of the NOTCH-signaling pathway (36) and p300, a transcriptional co-activator in the NOTCH1 pathway, functions as a histone acetyltransferase and regulates transcription via chromatin remodeling. Furthermore, p300 also plays a crucial role in cell proliferation and differentiation (37).

Based on our results, we hypothesized that lncRNA SRA functions as a key regulator of various signaling mechanisms involved in EMT establishment and NOTCH signaling. Our data provide evidence, for the first time, that lncRNA SRA promotes EMT and NOTCH signaling in cervical cancer cells, potentially contributing to cervical cancer growth, invasion and migration. The clinical impact of lncRNA SRA expression and its potential therapeutic value in the treatment of advanced cervical cancer patients needs to be evaluated in future studies.

In conclusion, these findings showed that lncRNA SRA is correlated with motility and invasiveness in cervical cancer cells. Furthermore, lncRNA SRA promoted cervical cancer progression by inducing cell migration and invasion via upregulation of MMP-2, MMP-9, VEGF, as well as genes related to EMT and the NOTCH signaling pathway. Therefore, lncRNA SRA constitutes a potential therapeutic target and prognostic marker for cervical cancer.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (grant nos. NRF-2015R1A2A2A01008162 and NRF-2015R1C1A2A01053516).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- siNC

negative-control siRNA

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SRA

steroid receptor RNA activator

References

- 1.Kodama J, Seki N, Masahiro S, Kusumoto T, Nakamura K, Hongo A, Hiramatsu Y. Prognostic factors in stage IB-IIB cervical adenocarcinoma patients treated with radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:413–417. doi: 10.1002/jso.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noordhuis MG, Fehrmann RS, Wisman GB, Nijhuis ER, van Zanden JJ, Moerland PD, Ver Loren van Themaat E, Volders HH, Kok M, ten Hoor KA, et al. Involvement of the TGF-beta and beta-catenin pathways in pelvic lymph node metastasis in early-stage cervical cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1317–1330. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez DS, Hoage TR, Pritchett JR, Ducharme-Smith AL, Halling ML, Ganapathiraju SC, Streng PS, Smith DI. Long, abundantly expressed non-coding transcripts are altered in cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:642–655. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guttman M, Donaghey J, Carey BW, Garber M, Grenier JK, Munson G, Young G, Lucas AB, Ach R, Bruhn L, et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinn JL, Kertesz M, Wang JK, Squazzo SL, Xu X, Brugmann SA, Goodnough LH, Helms JA, Farnham PJ, Segal E, et al. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by non-coding RNAs. Cell. 2007;129:1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ponting CP, Oliver PL, Reik W. Evolution and functions of long non-coding RNAs. Cell. 2009;136:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hung T, Wang Y, Lin MF, Koegel AK, Kotake Y, Grant GD, Horlings HM, Shah N, Umbricht C, Wang P, et al. Extensive and coordinated transcription of non-coding RNAs within cell-cycle promoters. Nat Genet. 2011;43:621–629. doi: 10.1038/ng.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu C, Wu HT, Zhu N, Shi YN, Liu Z, Ao BX, Liao DF, Zheng XL, Qin L. Steroid receptor RNA activator: Biologic function and role in disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;459:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan R, Wang K, Peng R, Wang S, Cao J, Wang P, Song C. Genetic variants in lncRNA SRA and risk of breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:22486–22496. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussein-Fikret S, Fuller PJ. Expression of nuclear receptor coregulators in ovarian stromal and epithelial tumours. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;229:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper C, Guo J, Yan Y, Chooniedass-Kothari S, Hube F, Hamedani MK, Murphy LC, Myal Y, Leygue E. Increasing the relative expression of endogenous non-coding steroid receptor RNA activator (SRA) in human breast cancer cells using modified oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4518–4531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colley SM, Leedman PJ. Steroid Receptor RNA Activator - A nuclear receptor coregulator with multiple partners: Insights and challenges. Biochimie. 2011;93:1966–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper C, Vincett D, Yan Y, Hamedani MK, Myal Y, Leygue E. Steroid Receptor RNA Activator bi-faceted genetic system: Heads or Tails? Biochimie. 2011;93:1973–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carninci P, Kasukawa T, Katayama S, Gough J, Frith MC, Maeda N, Oyama R, Ravasi T, Lenhard B, Wells C, et al. RIKEN Genome Exploration Research Group and Genome Science Group (Genome Network Project Core Group): The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science. 2005;309:1559–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1112014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris KV, Vogt PK. Long antisense non-coding RNAs and their role in transcription and oncogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2544–2547. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.13.12145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinger ME, Amaral PP, Mercer TR, Pang KC, Bruce SJ, Gardiner BB, Askarian-Amiri ME, Ru K, Soldà G, Simons C, et al. Long non-coding RNAs in mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency and differentiation. Genome Res. 2008;18:1433–1445. doi: 10.1101/gr.078378.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall PA, Russell SH. New perspectives on neoplasia and the RNA world. Hematol Oncol. 2005;23:49–53. doi: 10.1002/hon.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, Tsai MC, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–1076. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HJ, Lee DW, Yim GW, Nam EJ, Kim S, Kim SW, Kim YT. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR is associated with human cervical cancer progression. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:521–530. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim HJ, Eoh KJ, Kim LK, Nam EJ, Yoon SO, Kim KH, Lee JK, Kim SW, Kim YT. The long non-coding RNA HOXA11 antisense induces tumor progression and stemness maintenance in cervical cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:83001–83016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curran S, Murray GI. Matrix metalloproteinases: Molecular aspects of their roles in tumour invasion and metastasis. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:1621–1630. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biewenga P, van der Velden J, Mol BW, Stalpers LJ, Schilthuis MS, van der Steeg JW, Burger MP, Buist MR. Prognostic model for survival in patients with early stage cervical cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:768–776. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carmeliet P. VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology. 2005;69(Suppl 3):S4–S10. doi: 10.1159/000088478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burger RA. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies. J Gynecol Oncol. 2010;21:3–11. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2010.21.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. A perspective on cancer cell metastasis. Science. 2011;331:1559–1564. doi: 10.1126/science.1203543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramis-Conde I, Chaplain MA, Anderson AR, Drasdo D. Multi-scale modelling of cancer cell intravasation: The role of cadherins in metastasis. Phys Biol. 2009;6:016008. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/6/1/016008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morin PJ. beta-catenin signaling and cancer. BioEssays. 1999;21:1021–1030. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199912)22:1<1021::AID-BIES6>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin TA, Goyal A, Watkins G, Jiang WG. Expression of the transcription factors snail, slug, and twist and their clinical significance in human breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:488–496. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calaf GM, Balajee AS, Montalvo-Villagra MT, Leon M, Daniela NM, Alvarez RG, Roy D, Narayan G, Abarca-Quinones J. Vimentin and Notch as biomarkers for breast cancer progression. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:721–727. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: Cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timmerman LA, Grego-Bessa J, Raya A, Bertrán E, Pérez-Pomares JM, Díez J, Aranda S, Palomo S, McCormick F, Izpisúa-Belmonte JC, et al. Notch promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:99–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.276304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Z, Banerjee S, Li Y, Rahman KM, Zhang Y, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of notch-1 inhibits invasion by inactivation of nuclear factor-kappaB, vascular endothelial growth factor, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2778–2784. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nair P, Somasundaram K, Krishna S. Activated Notch1 inhibits p53-induced apoptosis and sustains transformation by human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncogenes through a PI3K-PKB/Akt-dependent pathway. J Virol. 2003;77:7106–7112. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.7106-7112.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masuda S, Kumano K, Shimizu K, Imai Y, Kurokawa M, Ogawa S, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Hirai H, Chiba S. Notch1 oncoprotein antagonizes TGF-beta/Smad-mediated cell growth suppression via sequestration of co-activator p300. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:274–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klinakis A, Szabolcs M, Politi K, Kiaris H, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Efstratiadis A. Myc is a Notch1 transcriptional target and a requisite for Notch1-induced mammary tumorigenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9262–9267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603371103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu ZH, Dai XM, Du B. Hes1: A key role in stemness, metastasis and multidrug resistance. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16:353–359. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1016662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oswald F, Täuber B, Dobner T, Bourteele S, Kostezka U, Adler G, Liptay S, Schmid RM. p300 acts as a transcriptional co-activator for mammalian Notch-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7761–7774. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.22.7761-7774.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]