Abstract

Introduction

This is a nationally representative study of rural–urban disparities in the prevalence of probable dementia and cognitive impairment without dementia (CIND).

Methods

Data on non-institutionalized U.S. adults from the 2000 (n=16,386) and 2010 (n=16,311) cross-sections of the Health and Retirement Study were linked to respective Census assessments of the urban composition of residential census tracts. Relative risk ratios (RRR) for rural–urban differentials in dementia and CIND respective to normal cognitive status were assessed using multinomial logistic regression. Analyses were conducted in 2016.

Results

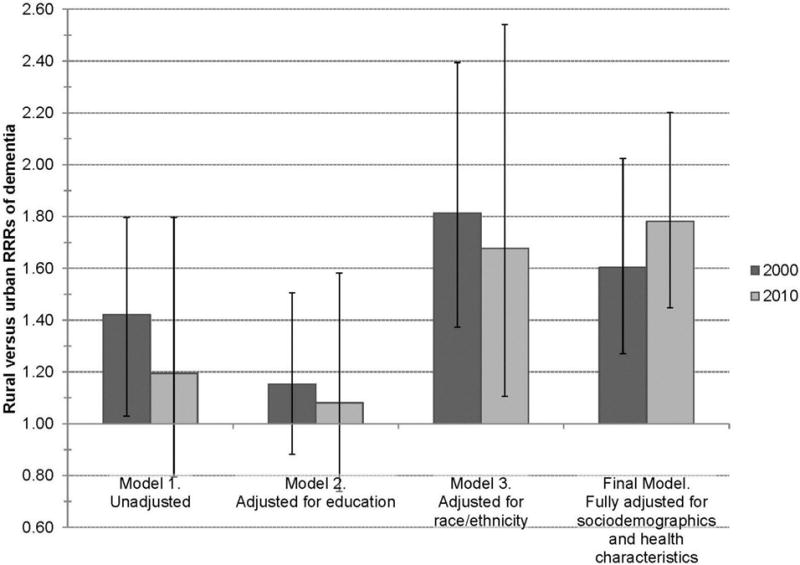

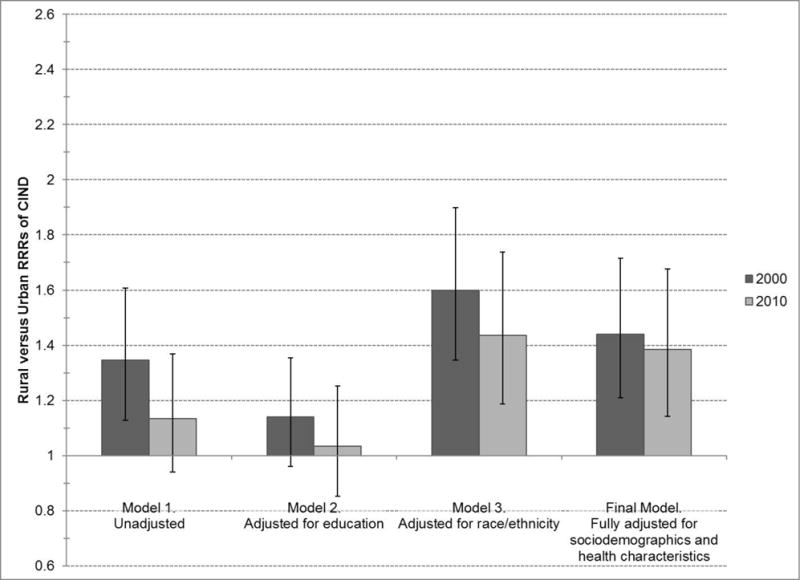

Unadjusted prevalence of dementia and CIND in rural and urban tracts converged so that rural disadvantages in the relative risk of dementia (RRR=1.42, 95% CI=1.10, 1.83) and CIND (RRR=1.35, 95% CI=1.13, 1.61) in 2000 no longer reached statistical significance in 2010. Adjustment for the strong protective role of educational attainment reduced rural disadvantages in 2000 to statistical nonsignificance whereas adjustment for race/ethnicity resulted in a statistically significant increase in RRRs in 2010. Full adjustment for sociodemographic and health factors revealed persisting rural disadvantages for dementia and CIND in both periods with RRR in 2010 for dementia of 1.79 (95% CI=1.31, 2.43) and for CIND of 1.38 (95% CI=1.14, 1.68).

Conclusions

Larger gains in rural adults’ cognitive functioning between 2000 and 2010 that are linked with increased educational attainment demonstrate long-term public health benefits of investment in secondary education. Persistent disadvantages in cognitive functioning among rural adults compared with sociodemographically similar urban peers highlights the importance of public health planning for more rapidly aging rural communities.

INTRODUCTION

More than a decade has passed since the U.S. DHHS released a chart book on the health of the nation that featured the differences in urban and rural health and thereby galvanized action around addressing urban–rural health differentials in the U.S. as a form of population health disparities.1,2 Since then, diseases of aging such as cognitive impairment and dementia have garnered attention at the highest levels of government.3,4 The more rapid pace of population aging in rural communities5 combined with longstanding health care and human services challenges6,7 draws into focus the likely unique susceptibility of rural communities to diseases of aging such as dementia and cognitive impairment. Unfortunately, very little is known about differences in cognitive impairment between urban and rural areas in the U.S.8 There is no known evidence from a nationally representative sample on either the magnitude or potential persistence of rural–urban disparities in cognitive impairment in the U.S. population.

Despite the lack of knowledge about potential differences in rural versus urban older adult cognitive health, studies consistently demonstrate that rural residents have higher rates of chronic conditions and morbidities thought to be precursors of cognitive impairment (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle1,7,9). Poorer health outcomes among rural residents are typically associated with poorer quality and reduced access to public health preventive health infrastructure, with reduced access not only as a result of geographic distance but also reduced public health supply, capacity, and quality.7

In addition, studies on rural–urban disparities have increasingly drawn attention to social determinants of health.10–12 Among these factors, educational opportunities may play a particularly important role in rural–urban disparities for cognitive health due both to the unique contribution of education in promoting cognitive resilience,13–15 and historical contribution of early twentieth century improvements in secondary schooling in driving regional differences in wealth.16 Over the last five decades increases in educational attainment have proceeded more rapidly in rural than urban areas; however, educational differentials persist, with rural areas continuing to lag behind urban areas in college and advanced degree completion.17,18 It is unclear whether the gains in educational attainment by rural populations may have translated into secular change in cognitive functioning among older rural adults.

Two decades ago a review of the literature on dementing illnesses in rural populations highlighted the paucity of population-based evidence,19 a gap which persists in the two most recent systematic reviews of geographic influences on cognitive aging in which only four studies on rural–urban differentials were identified, all from outside of the U.S.20,21 Among the two known U.S. studies to consider rural–urban differentials, a lack of population generalizability22 and measurement limitations8 were cited as explanations for null and unexpected results. Despite the paucity of evidence, European studies in Spain, Portugal, and Ireland have reported a higher prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia in rural than urban areas due at least in part to differences in sociodemographic composition of the populations by age and education.20

This study is the first known to the authors that analyzes rural–urban differentials in the prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia in a nationally representative sample of the U.S. older adult population, charting the trends in these urban–rural differentials and their sociodemographic determinants between 2000 and 2010.

METHODS

Study Sample

Data came from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), an ongoing, multicohort panel survey of U.S. older adults that is nationally representative of non-institutionalized adults aged >50 years. Details of the design have been previously described.23 All HRS respondents provided oral consent for the data used in this analysis. The study was approved by the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee, which is the RAND IRB. The 2000 and 2010 HRS panels for adults aged ≥55 years employed a repeated-cross section approach to data analysis.13,14 Total response rates for the HRS have been ≥88% in each wave.24 After excluding respondents who were missing information on residential census tracts (1.7% and 1.3% of the population in each respective year) and respondents who were missing data on one or more of the individual characteristics described below (respectively 1.5% and 2.9% in each year). Although less than 5% of the sample was excluded due to missing data, these respondents were more likely to have cognitive impairment without dementia (CIND) and probable dementia (hereafter referred to as dementia) (p<0.05) in both waves. The final analytic samples included 16,386 respondents in 2000 and 16,311 respondents in 2010.

Measures

Cognitive functioning was measured identically in 2000 and 2010 using a validated classification methodology.25 For self-reporting adults, the 27-point modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status is used to categorize cognitive functioning as CIND or dementia on the basis of immediate and delayed word call; the serial sevens subtraction test for working memory, and backward counting for attention and processing speed. Cut points for dementia (i.e., a score of 0–6), CIND (i.e., a score of 7–11), and normal (i.e., a score of 12–27) were defined on the basis of clinically assessed prevalence of these statuses in the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS).25

A proxy respondent—usually a spouse or other family member—is sought for respondents who are unwilling or unable to complete an interview themselves. Proxy respondents are essential to ensure coverage of those with cognitive impairments. In the 2000 and 2010 waves, 8.6% and 4.8%, respectively, of respondents provided data by proxy. Proxy-reported respondents are categorized as being normal, CIND or having dementia using proxy- and interviewer-assessments of cognition and the instrumental activities of daily living. Lack of inclusion of HRS proxy-respondents has been identified as an important source of bias in assessing secular trends in cognitive functioning.14

The authors measured the percentage urban composition of the respondents’ residential census tract by linking individuals’ records in the public-use HRS to the restricted-use HRS geographic data file. The U.S. Census Bureau data and measurement protocols were used to calculate the percentage of the population in the tract that is designated by the Census Bureau as being rural or urban. Because the Census Bureau makes urban and rural designations at the block level, the population residing in a tract may be 100% urban (i.e., wholly located in urban area), 100% rural, or contain both urban and rural territory. Urban areas are largely comprised of a core of densely settled census tracts or blocks that meet minimum population density requirements (the first criteria is for a block to have a density of 1,000 people per square mile) described in more detail elsewhere.26 Results showed that a four category definition of the tracts’ urban composition most parsimoniously allowed for 100% urban and 100% rural populations to be distinguished from two categories of tracts with mixed composition (e.g., those that were respectively 75.1%–99% urban and 0.1%–75% urban).

Individual sociodemographic characteristics were measured, including: age, gender, race, ethnicity, total number of children, marital status, highest educational attainment, and net total assets in 2000. Assets were assessed using a detailed question series with item nonresponse imputed by the data producers, and it was adjusted to 2000 U.S. dollars using the Consumer Price Index.27 Respondents self-reported whether or not the respondent was ever diagnosed with any of a series of health conditions, including: high blood pressure, cancer, diabetes, lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, or psychiatric conditions.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the sample in 2000 and 2010 and tested for differences by urbanicity employing survey design-based chi-square statistics. Multinomial logistic regression models were used to assess the rural–urban differential in the relative risk ratios (RRRs) for the respective prevalence of CIND and dementia relative to normal cognitive status in 2000 and 2010. All analyses employ the respective 2000 and 2010 sample weights provided by the data producers to make nationally representative inferences, and all analyses adjust for the stratified sampling and clustering of households within census tracts. Analyses were estimated in 2016 using the “svy” survey package in Stata, version 13.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics in Table 1 show that the distribution of cognitive functioning in 2000 varied significantly by urbanicity, such that dementia was significantly more prevalent in rural than urban areas with a rate of 7.1% (95% CI=5.8, 8.7) vs 5.4% (95% CI=4.9, 5.9). CIND was similarly more prevalent in rural than urban areas. By contrast, 10 years later the distribution of cognitive functioning no longer varied significantly by urbanicity and both dementia and CIND had declined across all urbanicity groups. Improvements in cognitive functioning, however, were largest in rural areas.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of U.S. Older Adults Aged >55 Years and Older by the Percent Urbanicitya

| 2000 (n=16,386) | 2010 (n=16,311) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Characteristics | 100% urban (n=9,63 0) |

Mixed urban (n=2,466) |

Mixed rural (n=2,430) |

100% Rural (n=1,860) |

100% urban (n=9,744) |

Mixed urban (n=2,666) |

Mixed rural (n=2,239) |

100% rural (n=1,662) |

| Cognitive functionb | ||||||||

| Normal | 78.7 | 77.6 | 77.8 | 73.1 | 80.7 | 80.7 | 81.9 | 78.4 |

| CIND | 15.9 | 16.5 | 15.7 | 19.8 | 14.9 | 14.9 | 13.8 | 16.5 |

| Dementia | 5.4 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 7.1 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 5.1 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 43.5 | 45.5 | 45.6 | 45.5 | 44.5 | 46.0 | 47.3 | 46.9 |

| Female | 56.5 | 54.5 | 54.4 | 54.5 | 55.5 | 54.0 | 52.7 | 53.1 |

| Age groupsc | ||||||||

| 55–59 years | 23.2 | 21.8 | 25.9 | 24.6 | 27.3 | 24.7 | 23.5 | 21.8 |

| 60–69 years | 33.8 | 36.7 | 37.9 | 32.7 | 36.6 | 38.6 | 42.9 | 42.3 |

| 70–79 years | 28.4 | 27.7 | 24.8 | 28.3 | 21.1 | 23.4 | 22.0 | 22.3 |

| ≥80 years | 14.7 | 13.8 | 11.4 | 14.4 | 15.0 | 13.3 | 11.6 | 13.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 77.2 | 88.5 | 92.7 | 89.3 | 73.3 | 82.3 | 89.9 | 90.5 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 12.1 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 6.7 | 12.8 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 4.1 |

| Hispanic | 8.2 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 10.5 | 8.4 | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.7 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 59.4 | 69.1 | 70.3 | 66.7 | 60.2 | 70.1 | 71.9 | 70.3 |

| Separated/divorced | 13.4 | 9.4 | 8.3 | 6.8 | 16.0 | 11.4 | 11.0 | 8.4 |

| Widowed | 23.0 | 19.4 | 19.7 | 23.3 | 16.4 | 14.4 | 12.8 | 17.9 |

| Never married | 4.2 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 7.4 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 3.4 |

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| <12 years | 21.9 | 23.7 | 27.4 | 30.4 | 14.1 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 15.2 |

| 12 years, high school | 52.9 | 55.3 | 54.2 | 53.5 | 49.7 | 53.4 | 58.5 | 60.3 |

| diploma or GED | ||||||||

| >12 years | 25.2 | 21.0 | 18.4 | 16.1 | 36.2 | 32.3 | 27.2 | 24.5 |

| Total household assets in dollarsc | 381,617 | 397,897 | 346,030 | 382,659 | 395,843 | 367,800 | 357,234 | 408,353 |

| High blood pressureb,c | ||||||||

| Ever diagnosed | 50.0 | 47.2 | 49.6 | 50.9 | 57.8 | 59.2 | 60.9 | 58.4 |

| Diabetesb,c | ||||||||

| Ever diagnosed | 15.2 | 14.1 | 14.3 | 15.0 | 22.2 | 21.1 | 21.8 | 20.9 |

| Cancerc | ||||||||

| Ever diagnosed | 12.8 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 12.2 | 15.1 | 16.7 | 13.3 | 13.7 |

| Lung disease | ||||||||

| Ever diagnosed | 8.8 | 9.4 | 10.1 | 11.2 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 12.5 | 10.9 |

| Heart diseaseb,c | ||||||||

| Ever diagnosed | 22.6 | 22.1 | 24.0 | 24.2 | 23.2 | 24.4 | 25.6 | 25.0 |

| Strokeb,c | ||||||||

| Ever diagnosed | 6.8 | 5.7 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 5.5 | 6.7 | 6.0 |

| Psychiatric conditionb,c | ||||||||

| Ever diagnosed | 13.2 | 12.2 | 14.1 | 14.3 | 18.2 | 17.4 | 20.4 | 17.4 |

All statistics are sample-weighted and adjusted for the complex sampling design of the HRS. Design-based chi-square F-statistics for distribution of characteristics by urbanicity all have p-value <0.05 unless otherwise indicated.

Design-based chi-square F-statistic p>0.05 in 2010.

Design-based chi-square F-statistic p>0.05 in 2000.

CIND, cognitive impairment with no dementia; GED, general equivalency diploma; HRS, Health and Retirement Study.

Concurrent with the differences in the distribution of cognitive functioning, there were also statistically significant sociodemographic differences in the characteristics of rural and urban dwelling older adults, some of which involved changes over time. Racial and ethnic differences in the distribution of older adults by urbanicity are manifested in both 2000 and 2010, with minorities comprising an even larger relative proportion of the population of urban areas than rural areas in 2010 than 2000. Rural–urban differentials in education showed notable changes between 2000 and 2010, with the proportion of older adults with <12 years of education dropping by about half in rural areas between 2000 and 2010.

The magnitude of urbanicity differentials in dementia and CIND in 2000 and 2010 were estimated holding constant the individual characteristics displayed in Table 1 using multinomial logistic regressions for the RRRs of dementia and CIND versus normal cognitive status. As shown in Table 2, in 2000, the fully adjusted RRR of dementia was 60% higher in rural than urban areas (95% CI=1.27, 2.02), and that CIND was 44% higher (95% CI=1.21, 1.72). In 2010, similarly high rural–urban differentials were found: RRRs for dementia and CIND were ≅80% (95% CI=1.31, 2.43) and 40% (95% CI=1.14, 1.68) higher, respectively, in rural than urban areas. The sociodemographic factors age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment and household assets were all strong predictors of RRR for dementia and CIND and they were of a similar magnitude in 2000 and 2010.

Table 2.

Fully-adjusted Rural Versus Urban Relative Risk Ratios for Cognitive Status of U.S. Older Adults

| 2000 | 2010 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Dementia versus normal | CIND versus normal | Dementia versus normal | CIND versus normal | |

|

|

||||

| Characteristics | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) | RRR (95% CI) |

| Urbanicity of residential census tract (ref: 100% urban) | ||||

| Mixed urban (75% to 99% urban) | 1.51 (1.18, 1.94) | 1.24 (1.06, 1.45) | 1.33 (1.04, 1.71) | 1.15 (0.99, 1.34) |

| Mixed rural (75% to 99% rural) | 1.63 (1.30, 2.06) | 1.22 (1.03, 1.43) | 1.42 (1.11, 1.83) | 1.10 (0.94, 1.29) |

| Rural (0% urban) | 1.60 (1.27, 2.02) | 1.44 (1.21, 1.72) | 1.79 (1.31, 2.43) | 1.38 (1.14, 1.68) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (vs female) | 1.41 (1.19, 1.67) | 1.44 (1.29, 1.61) | 1.17 (0.96, 1.42) | 1.35 (1.20, 1.51) |

| Age categories (ref: 55–59 years) | ||||

| 60–69 years | 2.10 (1.42, 3.11) | 1.34 (1.12, 1.60) | 1.61 (1.03, 2.52) | 1.19 (1.00, 1.42) |

| 70–79 years | 6.84 (4.63, 10.11) | 3.08 (2.56, 3.70) | 5.03 (3.29, 7.53) | 2.10 (1.76, 2.48) |

| >80 years | 26.03 (17.52, 38.68) | 6.40 (5.23, 7.85) | 26.04 (16.95, 40.01) | 6.06 (4.97, 7.36) |

| Race/ethnicity (ref: non-Hispanic white) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 5.18 (4.13, 6.50) | 2.83 (2.43, 3.31) | 4.89 (3.83, 6.24) | 2.95 (2.52, 3.45) |

| Hispanic | 2.24 (1.76, 3.27) | 2.21 (1.82, 2.70) | 2.93 (2.20, 3.90) | 1.99 (1.63, 2.42) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 4.08 (2.55, 6.52) | 1.85 (1.29, 2.64) | 3.08 (1.78, 5.32) | 2.00 (1.42, 2.81) |

| Number of children | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) |

| Marital status (ref: married) | ||||

| Separated/divorced | 0.78 (0.55, 1.09) | 1.05 (0.86, 1.27) | 1.24 (0.90, 1.70) | 1.06 (0.89, 1.28) |

| Widowed | 1.18 (0.97, 1.47) | 1.23 (1.08, 1.40) | 1.56 (1.28, 1.91) | 1.13 (0.98, 1.30) |

| Never married | 1.31 (0.80, 2.12) | 1.19 (0.85, 1.65) | 1.53 (0.94, 2.49) | 1.31 (0.95, 1.78) |

| Educational attainment (ref: <12 years) | ||||

| 12 years, high school diploma or GED | 0.27 (0.22, 0.32) | 0.40 (0.36, 0.45) | 0.23 (0.19, 0.27) | 0.32 (0.28, 0.37) |

| >12 years | 0.14 (0.10, 0.19) | 0.17 (0.14, 0.20) | 0.11 (0.08, 0.15) | 0.16 (0.13, 0.19) |

| Household assets (natural log of dollars) | 0.94 (0.92, 0.95) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.98) |

| High blood pressure ever diagnosed (vs never) | 0.86 (0.73, 1.02) | 1.04 (0.93, 1.16) | 1.10 (0.89, 1.37) | 1.02 (0.91, 1.15) |

| Cancer ever diagnosed (vs. never) | 0.81 (0.64, 1.02) | 0.93 (0.80, 1.08) | 0.90 (0.72, 1.13) | 0.89 (0.76, 1.05) |

| Diabetes ever diagnosed (vs. never) | 1.34 (1.10, 1.65) | 1.20 (1.05, 1.36) | 1.15 (0.93, 1.41) | 1.25 (1.09, 1.42) |

| Lung disease ever diagnosed (vs. never) | 1.07 (0.85, 1.34) | 1.18 (1.00, 1.38) | 0.89 (0.69, 1.16) | 1.22 (1.01, 1.45) |

| Heart disease ever diagnosed (vs. never) | 1.24 (1.04, 1.47) | 1.11 (0.99, 1.25) | 0.86 (0.70, 1.05) | 1.17 (1.03, 1.32) |

| Stroke ever diagnosed (vs. never) | 3.58 (2.84, 4.52) | 1.69 (1.40, 2.04) | 3.75 (2.93, 4.81) | 1.74 (1.44, 2.10) |

| Psychiatric condition ever diagnosed (vs. never) | 2.34 (1.92, 2.85) | 1.36 (1.18, 1.57) | 1.62 (1.28, 2.05) | 1.22 (1.05, 1.41) |

Notes: Boldface indicates statistically significant estimates (p<0.05).

All statistics are sample-weighted and adjusted for the complex sampling design of the HRS.

RRR, relative risk ratio; CIND, cognitive impairment with no dementia; GED, general equivalency diploma; HRS, Health and Retirement Study.

There were also increased risks of dementia and CIND for mixed rural and mixed urban areas respective to urban areas. For example, there appeared to be a dose–response effect in 2010 for the dementia outcome such that mixed rural areas experienced a 42% higher RRR, which was larger than the 33% higher RRR for mixed urban areas. However, the RRRs for these mixed urban and mixed rural categories were less consistent between 2000 and 2010, with larger (though not statistically significantly different) RRR observed in 2000 than 2010. Because of this inconsistency in associations for the mixed categories, the manuscript subsequently focuses on the 100% urban and 100% rural categories.

The authors then evaluated whether any of the individual characteristics could account for the 42% higher (unadjusted) RRR of dementia in rural than urban areas in 2000 depicted in Figure 1 and 35% (unadjusted) higher RRR of CIND in Figure 2. After sequentially adjusting for each characteristic, it was determined that education was highly protective (educational attainment >12 years conferred between 83% and 89% lower RRR and was the only factor to reduce these higher RRRs to statistical nonsignificance). Further assessment of the findings from Table 1 and Table 2 also indicated that educational attainment was the only compositional characteristic that was both a risk factor for cognitive impairment that is more prevalent among rural than urban older adults, and a risk factor for which the differences in prevalence among rural and urban older adults has diminished over the last decade. Taken together, these findings suggest that greater increases in educational attainment over a decade in rural areas could account for the larger crude reductions in dementia and CIND observed in 2000 and 2010 for rural compared with urban areas.

Figure 1.

Rural versus urban relative risk ratios (RRRs) of dementia versus normal cognitive status for U.S. community-dwelling adults aged >55 years in 2000 and 2010 in the Health and Retirement Study.a

aAll statistics are sample-weighted and adjusted for the complex sampling design of the Health and Retirement Study.

Figure 2.

Rural versus urban relative risk ratios (RRRs) of cognitive impairment with no probable dementia (CIND) versus normal cognitive status for U.S. community-dwelling adults aged >55 years in 2000 and 2010 in the Health and Retirement Study.a

aAll statistics are sample-weighted and adjusted for the complex sampling design of the Health and Retirement Study.

Through the sequential modeling of the individual characteristics, it was also determined that age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and wealth operated as suppressors of the rural disadvantage in dementia and CIND (attenuating the RRR of rural residence by as much as ≅20%), whereas the health conditions produced very little change in the RRRs. Among these variables, only adjustment for race/ethnicity resulted in a statistically significant increase in the RRR of dementia and CIND for rural versus urban areas in 2010. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the RRR for dementia and CIND were respectively 68% and 44% higher for rural than urban areas in 2010 after adjusting for the lower concentration of racial and ethnic minorities in rural than urban areas. It is noteworthy that there were no statistically significant racial/ethnic or gender differences in the associations of rural residence with dementia or CIND. Overall results found that after the compositional characteristics that predispose rural and urban populations to cognitive impairment are held constant—namely the respectively poorer educational attainment of rural populations and the increased minority concentration of urban populations—there have remained substantial, persistent disadvantages in older life cognitive functioning among rural older adults over the last decade.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to evaluate the differentials in cognitive functioning between rural and urban older adults over a 10-year period using a nationally representative sample of the U.S. Results identified both a closing of the rural–urban gap in crude unadjusted rates of dementia and CIND between 2000 and 2010 as well as a persistent rural–urban disparity in dementia and CIND that emerges once the individual sociodemographic and health characteristics of rural and urban areas are held constant. The disadvantages observed for residents living in mixed urban and mixed rural area compared with residents living in 100% urban areas were larger (though not statistically significantly different) in 2000 compared with 2010, although these trends were not consistent between 2000 and 2010. As rural America becomes more intertwined with urban areas such that the majority (54%) of all rural residents now reside in metropolitan areas,28 these mixed areas at the rural–urban interface, and any disparities in physical health and cognitive health experienced by residents of these heterogeneous rural areas need further research.

The declining rates of dementia and CIND observed here and their relationship with improvements in education provide new geographic detail to earlier research on trends in U.S. older adults cognitive functioning and their determinants.13,14,29 The question of whether improvements in cognition have been shared equally within the U.S. population has been identified as a major gap in the literature that so far has been addressed only with respect to racial and ethnic differentials.29 These findings amplify and extend this work by showing that, although older adults living in urban and rural areas both experienced a continuing decline in the rate of cognitive impairment reported previously,13,14 the decline was larger among those living in rural areas and produced a narrowing of the rural–urban gap. Moreover, there was a considerable decrease in the proportion of older adults with less than high school education in rural areas over this decade that reflects the rapid increase and spread of high school graduation between 1910 and 1940 documented elsewhere.16 Results also revealed that rural older adults’ lower educational attainment is the only sociodemographic characteristic that reduces the current cognitive impairment gap to statistical nonsignificance. Previous studies have identified increases in education as a source of improved cognition among U.S. older adults overall.13,14,29 These findings imply that increased education has also resulted in narrowed rural–urban disparities. Education may operate directly by establishing higher initial levels of cognition or improving capacity to employ brain networks to compensate for stressors and shocks.15 It may also operate indirectly by increasing cognitive activity related to work and leisure activities, or through improved health behaviors, healthcare access and healthcare utilization supporting cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health.13,14

The study also demonstrates that persistent inequalities in cognitive function emerge when the sociodemographic characteristics of rural and urban dwelling older adults are held constant, particularly racial and ethnic background. Previously documented gaps in medical, public health, and social service infrastructure in rural areas7 may be one potential source of these persisting rural disadvantages. For example, rural areas have a dearth of health professionals who can administer screening and diagnostic cognitive assessments and treat dementia.30,31 Thus, a minority, rural-dwelling older adult may experience disadvantages both by nature of being a minority with fewer access to resources and by nature of living in an rural area with lower advantages.

Another potential source of persistent rural disadvantages might involve the relationship between social engagement and healthy cognitive aging.32 There is mixed evidence, however, about the extent that rural geographic isolation also determines social isolation.11,33,34 This study was unable to account for social engagement or lifestyle factors which may vary by urbanicity, due to the lack of these measures at a wave temporally near the 2000 HRS wave for the entire sample. Future exploration of these relationships in the context of the persistence of rural–urban disparities identified in this study is warranted.

Limitations

A limitation faced by any study of rural health is the variety of federal definitions and measurement of urban and rural residence.35,36 The Census definition for census tracts was selected due to its greater geographic granularity. However, sensitivity analyses employing U.S. Department of Agriculture county-level Rural Urban Continuum Codes showed substantively similar findings. In addition, even with the relatively large sample size afforded by the HRS, this study was unable to evaluate possible regional variations in rural cultural conditions,2 which may prove important for future research informing public health, health care, and long-term care policy. Lastly, the categorization of dementia or CIND is based on a more limited set of cognitive tests than employed when making a clinical diagnosis. However, prior validation studies have shown a 78% concordance for dementia when using this more limited set of tests compared with the detailed ADAMS clinical evaluation conducted for a subsample of the HRS respondents.25

CONCLUSIONS

Improvement in cognitive aging among older U.S. rural adults over the last decade suggests there have been long-term public health dividends to the investment in secondary education made in the early twentieth century. This connection strengthens the evidence for the relevance of a “Health in All Policies” approach with collaboration between health systems, public health agencies and educational systems, and highlights the importance of a long-range view towards addressing the social determinants of health across the life course. More immediately, the documented persistence of cognitive aging disadvantages among rural adults relative to their sociodemographically similar urban-dwelling peers, combined with the more rapid pace of population aging in rural communities, reinforces the need for continued investment in rural health care and long-term services and supports by federal, state, and local agencies.

Acknowledgments

The research presented in this paper is that of the authors and does not reflect the official policy of NIH. This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) at NIH (R01 AG043960). The Health and Retirement Study is funded by the NIA (U01 AG009740), and performed at the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. RAND Health and Retirement Study Data, Version N. Produced by the RAND Center for the Study of Aging, with funding from the NIA and the Social Security Administration. Dr. Langa received additional support from NIA grants P30 AG053760 and P30 AG024824.

Weden led the inception of the paper, analyses, and interpretation of findings, and she drafted the paper. Shih contributed to the analysis plan and helped draft sections of the paper. Kabeto conducted the analyses, contributed to the interpretation of findings and reviewed the paper draft. Langa reviewed the analytic findings and paper draft. The authors are also grateful to Christine Peterson for assistance with data construction.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Eberhardt MS, Ingram DD, Makuc DM, et al. Urban and Rural Health Chartbook Health, United States, 2001. Hyattsville, MD: Center for Health Statistics; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartley D. Rural Health Disparities, Population Health, and Rural Culture. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1675–1678. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1675. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. DHHS. National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s. Disease: 2016 Update; 2016. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/205581/NatlPlan2016.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, Langa KM. Monetary Costs of Dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glasgow N, Brown DL. Rural ageing in the United States: Trends and contexts. J Rural Stud. 2012;28(4):422–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.01.002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolin JN, Bellamy GR, Ferdinand AO, et al. Rural Healthy People 2020: New Decade, Same Challenges. J Rural Health. 2015;31(3):326–333. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12116. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris JK, Beatty K, Leider JP, Knudson A, Anderson BL, Meit M. The Double Disparity Facing Rural Local Health Departments. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:167–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122755. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abner EL, Jicha GA, Christian WJ, Schreurs BG. Rural-Urban Differences in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Diagnostic Prevalence in Kentucky and West Virginia. J Rural Health. 2016;32(3):314–320. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12155. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen M, Fan JX, Kowaleski-Jones L, Wan N. Rural–Urban Disparities in Obesity Prevalence Among Working Age Adults in the United States. Am J Health Promot. doi: 10.1177/0890117116689488. In press. Online February 1, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117116689488. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Singh GK, Siahpush M. Widening rural-urban disparities in life expectancy, U.S., 1969–2009. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(2):e19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogelsang EM. Older adult social participation and its relationship with health: Rural-urban differences. Health Place. 2016;42:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.09.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeng D, You W, Mills B, Alwang J, Royster M, Anson-Dwamena R. A closer look at the rural-urban health disparities: Insights from four major diseases in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Soc Sci Med. 2015;140:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langa KM, Larson EB, Crimmins EM, et al. A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):51–58. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6807. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langa KM, Larson EB, Karlawish JH, et al. Trends in the prevalence and mortality of cognitive impairment in the United States: is there evidence of a compression of cognitive morbidity? Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(2):134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.01.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stern Y. Cognitive reserve and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(2):112–117. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000213815.20177.19. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.wad.0000213815.20177.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldin C. America’s graduation from high school: The evolution and spread of secondary schooling in the twentieth century. J Econ Hist. 1998;58(2):345–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700020544. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Rural America At A Glance. Economic Brief Number 26. 2014 www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=42897. Accessed March 27, 2017.

- 18.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Rural Education. 2016 www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/employment-education/rural-education/. Accessed March 27, 2017.

- 19.Keefover RW, Rankin ED, Keyl PM, Wells JC, Martin J, Shaw J. Dementing illnesses in rural populations: The need for research and challenges confronting investigators. J Rural Health. 1996;12(3):178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1996.tb00792.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.1996.tb00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cassarino M, Setti A. Environment as ‘Brain Training’: A review of geographical and physical environmental influences on cognitive ageing. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;23(Pt B):167–182. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russ TC, Batty GD, Hearnshaw GF, Fenton C, Starr JM. Geographical variation in dementia: systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(4):1012–1032. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys103. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mattos MK, Snitz BE, Lingler JH, Burke LE, Novosel LM, Sereika SM. Older Rural- and Urban-Dwelling Appalachian Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Rural Health. 2017;33(2):208–216. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12189. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauser RM, Willis RJ. Survey design and methodology in the health and retirement study and the Wisconsin longitudinal study. Popul Dev Rev. 2004;30:209–235. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) Sample Sizes and Response Rates. 2011 http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/sampleresponse.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2017.

- 25.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(Suppl 1):i162–171. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr048. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K, Fields A. Defining Rural at the US Census. ACSGEO-1, U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2016. www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/reference/ua/Defining_Rural.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Updated CPI-U-RS, All items, 1977–2015. 2016 www.bls.gov/cpi/cpiurs.htm. Accessed March 27, 2017.

- 28.Lichter DT, Ziliak JP. The Rural-Urban Interface: New Patterns of Spatial Interdependence and Inequality in America. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2017;672(1):6–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716217714180. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheffield KM, Peek MK. Changes in the prevalence of cognitive impairment among older Americans, 1993–2004: overall trends and differences by race/ethnicity. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(3):274–283. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr074. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson LE, Bazemore A, Bragg EJ, Xierali I, Warshaw GA. Rural-Urban Distribution of the U.S. Geriatrics Physician Workforce. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):699–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03335.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Academy of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Voshaar RCO, et al. Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;22:39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glasgow N. Rural/urban patterns of aging and caregiving in the United States. J Fam Issues. 2000;21(5):611–631. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251300021005005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baernholdt M, Yan GF, Hinton I, Rose K, Mattos M. Quality of Life in Rural and Urban Adults 65 Years and Older: Findings From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Rural Health. 2012;28(4):339–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00403.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall SA, Kaufman JS, Ricketts TC. Defining urban and rural areas in U.S. epidemiologic studies. J Urban Health. 2006;83(2):162–175. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9016-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-005-9016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hart LG, Larson EH, Lishner DM. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1149–1155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042432. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.042432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]