Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors have become first line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Their use commonly leads to hypertension, but their effects on long-term renal function are not known. In addition, it has been suggested that the development of hypertension is linked to treatment efficacy. The objective of this study was to determine the effects of these drugs on long-term renal function, especially in those with renal dysfunction at baseline, and to examine the role of hypertension on these effects. Serum creatinine measurements were used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate for 130 renal cell carcinoma patients who were treated with this class of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. New or worsening hypertension was defined by documented start or addition of antihypertensive medications. Overall, the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with estimated glomerular filtration < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or ≥ 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was not associated with a decline in long-term renal function. During follow up, 41 patients developed new or worsening hypertension within 30 days from first drug administration and this was not linked to further reductions in glomerular filtration. These patients appeared to survive longer than those who did not develop hypertension within 30 days, although this was not statistically significant (P=0.07). Our findings suggest that the use of vascular endothelial growth factor tyrosine kinase inhibitors does not adversely affect long-term renal function even in the setting of new onset hypertension or reduced renal function at baseline.

Keywords: renal cell carcinoma, hypertension, glomerular filtration rate, VEGF, tyrosine kinase inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) represents 2–3% of adult cancers worldwide, with 62,700 new cases and 14,240 deaths in the United States in 2015.1,2 The highest incidence occurs in males aged 50–70 years, and established risk factors include smoking, obesity, and hypertension (HTN).3 For those with localized tumors, the first-line treatment is surgical, but up to one third of those treated develop metastatic recurrence within 10 years, and up to 30% of all patients with RCC first present with metastatic disease.4–6 For these patients with advanced disease, systemic therapy is usually indicated.

Inactivation of von Hippel-Lindau suppressor is common in RCC and results in stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor and overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), an important promoter of tumor angiogenesis.7,8 Understanding of this critical mechanism led to the development of targeted therapies including the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab, and more recently, VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (VEGFR-TKIs), which are now used as standard of treatment for metastatic RCC (mRCC). Because VEGF is also normally expressed in several cell types, VEGF inhibition can interfere with physiologic processes and lead to several adverse effects. VEGF expressed in podocytes of the glomerulus activates VEGF receptors in the neighboring glomerular endothelium 9 and signals podocytes via autocrine mechanisms to promote survival and maintenance of the selective barrier to macromolecules.10 VEGF signaling also appears to play a role in vasodilation by activating nitric oxide (NO) synthase.11,12 Clinically, VEGFR-TKIs and bevacizumab have been associated with the development of renal thrombotic microangiopathy, proteinuria, and more commonly, HTN.9,13 In some case reports, these side effects are also associated with acute reductions in glomerular filtration rate (GFR).9,14–16

While the side effects associated with VEGF inhibition have been reported to resolve after drug discontinuation, HTN is hypothesized to be a biomarker of efficacy17 and can be controlled with standard antihypertensive drugs to allow continuation of cancer treatment.18 It remains unclear, however, whether the use of VEGFR-TKIs produces long-term adverse effects in renal function, especially in patients who already have renal dysfunction as a result of nephrectomy and/or medical co-morbidities. In this study, we examined the renal function of 130 mRCC patients who were treated with VEGFR-TKIs at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). We were particularly interested in the long-term effects of VEGFR-TKIs on renal function, especially in patients who had reduced renal function (estimated GFR (eGFR) < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) at baseline, as well as the role of new onset or worsening HTN on these effects and overall survival. We hypothesized that VEGFR-TKI therapy may adversely affect kidney function given the reported renal effects of this therapy, while at the same time the development of new or worsening HTN may impart survival benefit but would not affect kidney function.

METHODS

Study Patients

A retrospective chart analysis was performed after obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board at MSKCC. Protected health information was coded in accordance with the requirements of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. We identified patients who were diagnosed with RCC between January 2010 and June 2014, presented at MSKCC with distant metastases/systemic disease, and were planning to receive treatment with at least one VEGFR-TKI according to physician orders and/or dispensation by the MSKCC pharmacy. Specifically, we identified patients who received sunitinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, axitinib, tivozanib or cabozantinib. We excluded patients who on further review were found to never have taken the VEGFR-TKIs, who were receiving VEGFR-TKIs prior to treatment at MSKCC, or who did not have at least one post-VEGFR-TKI measurement of serum creatinine.

Data collection

The baseline for our study was the date of first administration of any VEGFR-TKI. The baseline characteristics collected included sex, race, body mass index, age at diagnosis, stage at diagnosis as defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer, smoking history, history of HTN, and history of diabetes. We also categorized each patient into one of three risk groups for mRCC based on five prognostic factors (Karnofsky performance status, serum lactate dehydrogenase, hemoglobin, corrected serum calcium, and history of nephrectomy) as identified by Motzer et al.19 For this study we collected dates for the first and last administrations of each VEGR-TKI, which allowed us to capture breaks between regimens of different drugs, but not breaks within one drug regimen. We recorded whether doses were reduced for each agent and coded the reason for discontinuation of a drug as progression of disease or adverse events. Serum creatinine values measured at MSKCC were collected starting from 30 days before first VEGFR-TKI administration, up to the most recent measurement. New or worsening HTN (new/worsening HTN) in our patients was defined by documented addition or change of antihypertensive medications with corresponding physician orders or assessments. The date of last follow up for survival analysis was noted by the most recent communication with the patient in the chart as of July 2015.

Analysis and statistical methods

We used serum creatinine to calculate eGFR values using the CKD-EPI formula20 as follows: eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) = 141 * min(SCr/κ,1)α × max(SCr/κ,1)−1.209 * 0.993Age * 1.018 [if female] * 1.159 [if black], where SCr is serum creatinine (mg/dL), κ is 0.7 for females and 0.9 for males, α is −0.329 for females and −0.411 for males, min indicates the minimum of Scr/κ or 1, and max indicates the maximum of Scr/κ or 1.

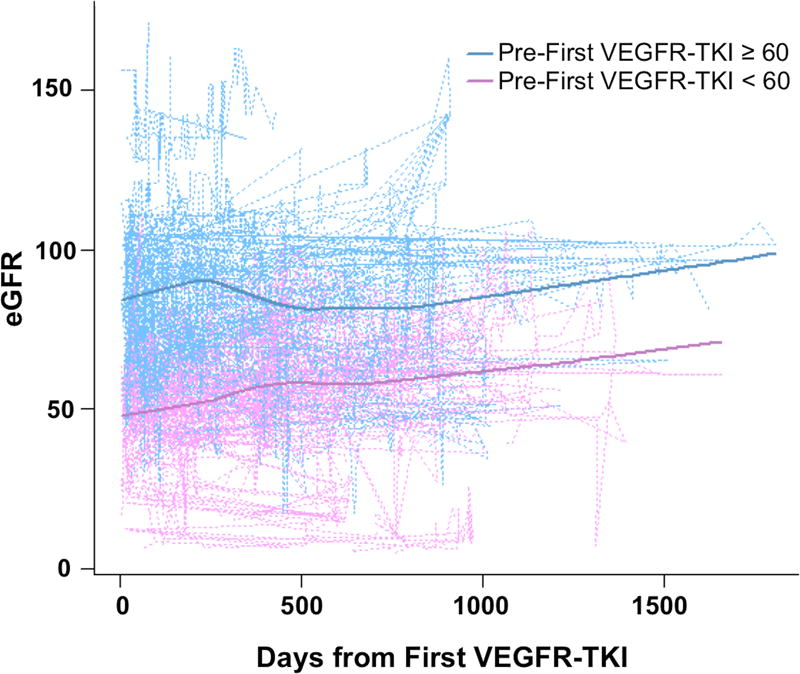

Patient characteristics were tabulated by baseline eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 vs. ≥ 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Tests for differences between groups were conducted using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test when continuous and Fisher’s exact test when categorical. Measurements of eGFR starting from initiation of VEGFR-TKI treatment were plotted over time for each patient using a spaghetti plot, and a locally weighted scatterplot smooth (lowess) was overlaid to show the average trajectory separately for those with baseline eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and those with baseline eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Overall survival (OS) times were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method from date of VEGFR-TKI initiation to date of death or last follow-up. Similarly, the Kaplan-Meier method estimated time to first new/worsening HTN during follow-up from time of VEGFR-TKI initiation. Patients who did not develop new/worsening HTN were censored at their date of last follow-up. The log-rank test was used for by-group comparisons. Cox regression was used for multivariable analysis.

In order to evaluate factors associated with eGFR over time, we fit a mixed effects model with a random intercept and random slope for each patient. The model included time as well as the factor of interest as fixed effects. This model accounts for the correlation between multiple eGFR measurements from each patient over time and allows for variation in individual baseline and trajectory of eGFR.

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 3.1.1 (R Core Development Team, Vienna, Austria) including the ‘survival’ and ‘nlme’ packages. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

We identified 130 patients with mRCC who took VEGFR-TKIs and met our other inclusion criteria for the study. The baseline chosen for analysis was the date of first administration of VEGFR-TKI. Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of our cohort overall, as well as for those with normal (≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) or abnormal (<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) baseline eGFR. A majority of these patients were white (89.2%) and male (70%) with a median age of 57 years overall. As shown in Table 1, patients with eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were younger (median age 56 vs. 61; P=0.008), more likely to have never smoked (54.5% vs. 30.2% never smoker; P=0.03), less likely to have prior history of HTN (57.1% vs. 81.1%; P=0.005), and less likely to have undergone a prior nephrectomy (44.2% vs. 83.0%; P< .001). There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of diabetes between the groups (P=0.14). Overall, most of the patients included in the study received long-term treatment but were often switched from one agent to another due to disease progression or adverse events. The cumulative treatment duration in Table 1 represents the total number of days that patients took VEGFR-TKIs and accounts for major treatment holidays and periods of treatment with agents of other pharmacologic classes. As shown in Table 1, there was no significant difference in the cumulative treatment duration (P=0.30) or number of VEGFR-TKI regimens (P=0.24) between those with normal and abnormal baseline renal function.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics stratified by baseline eGFR

| Baseline eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Overall | ≥60 | <60 | P value |

| N=77; 59.2% | N=53; 40.8% | |||

| Age at diagnosis, median (min, max) | 57 (14, 81) | 56 (14, 81) | 61 (42, 81) | 0.008 |

| BMI, median (min, max) | 27.3 (16.1, 49.4) | 26.7 (16.1, 43.9)* | 28.18 (19, 49.4) | 0.31 |

| Sex, N (%) | 0.17 | |||

| F | 39 (30) | 27 (35.1) | 12 (22.6) | |

| M | 91 (70) | 50 (64.9) | 41 (77.4) | |

| Race, N (%) | 0.30 | |||

| Asian | 5 (3.8) | 3 (3.9) | 2 (3.8) | |

| Black | 5 (3.8) | 5 (6.5) | 0 (0) | |

| No Answer | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Other | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.9) | |

| White | 116 (89.2) | 67 (87) | 49 (92.5) | |

| Stage at diagnosis, N (%) | 0.25 | |||

| I | 7 (5.4) | 2 (2.6) | 5 (9.4) | |

| II | 4 (3.1) | 3 (3.9) | 1 (1.9) | |

| III | 14 (10.8) | 7 (9.1) | 7 (13.2) | |

| IV | 104 (80) | 65 (84.4) | 39 (73.6) | |

| UNK | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Prior diabetes, N (%) | 30 (23.1) | 14 (18.2) | 16 (30.2) | 0.14 |

| Prior HTN, N (%) | 87 (66.9) | 44 (57.1) | 43 (81.1) | 0.005 |

| Cigarette smoking history, N (%) | 0.03 | |||

| Never | 58 (44.6) | 42 (54.5) | 16 (30.2) | |

| Former | 54 (41.5) | 27 (35.1) | 27 (50.9) | |

| Current | 17 (13.1) | 8 (10.4) | 9 (17.0) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Prior nephrectomy, N (%) | 78 (60.0) | 34 (44.2) | 44 (83.0) | <.001 |

| Risk group, N (%) | 0.09 | |||

| Favorable | 43 (33.1) | 20 (26) | 23 (43.4) | |

| Intermediate | 78 (60) | 50 (64.9) | 28 (52.8) | |

| Poor | 9 (6.9) | 7 (9.1) | 2 (3.8) | |

| Cumulative treatment duration, median (min, max) | 202 (1, 1286) | 200 (19, 1286)† | 209 (1, 1083)‡ | 0.30 |

| Number of VEGR-TKI regimens, N (%) | 0.24 | |||

| 1 | 69 (53.1) | 45 (58.4) | 24 (45.3) | |

| 2 | 51 (39.2) | 25 (32.5) | 26 (49.1) | |

| 3 | 9 (6.9) | 6 (7.8) | 3 (5.7) | |

| 4 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

Missing Data for N=1,

Missing Data for N=10,

Missing Data for N=7

abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HTN = hypertension; VEGFR-TKI = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

During follow-up, 64 patients died from any cause. The median OS was 2 years from first VEGFR-TKI administration (95% CI 1.6, 2.8), and survivors were followed for a median of 1.5 years (min=0.2, max=5.2). Those with baseline eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 appeared to have a survival advantage in comparison to the group with normal baseline renal function. However, after adjusting for all characteristics significantly associated with baseline eGFR in Table 1, this association did not retain significance (HR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.32 – 1.10).

To investigate renal function, we calculated eGFR using serum creatinine measurements. We first plotted these values versus time for all patients, starting after the first administration of VEGFR-TKI. Overall, our patients exhibited an upward trend in eGFR over time that appeared similar among those with baseline eGFR < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and those with baseline eGFR ≥ 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Figure 1). We used a mixed effects model to more quantitatively evaluate the association of baseline eGFR and eGFR over time. We found that the upward trend in eGFR was statistically significant, such that on average, a one day increase in time was associated with a 0.016 unit increase in eGFR (P=0.01). We also found that there was no significant interaction between days from first VEGFR-TKI and baseline eGFR (P=0.65), consistent with relatively parallel trends observed in Figure 1. We then looked at the association of other baseline characteristics with eGFR over time using univariable models (not shown). Including only the variables that were significant on univariable analysis, we fit a multivariable linear mixed model (Table 2). Here, we found that abnormal baseline eGFR, older age, and higher BMI were significantly associated with lower eGFR.

Figure 1.

Plot of eGFR over time for 130 mRCC patients starting at first administration of VEGFR-TKI, stratified by baseline eGFR. Dotted lines represent individual patients and solid lines represent lowess smoothing. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; VEGFR-TKI = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Table 2.

Multivariable linear mixed effects model for eGFR using characteristics with significant univariable association

| Characteristics | Estimate (SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline eGFR < 60 | −20.99 (3.86) | 0.02 |

| Days from first VEGFR-TKI | 0.02 (0.01) | <0.001 |

| Age at Diagnosis | −0.69 (0.14) | 0.01 |

| BMI | −0.38 (0.26) | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.15 | |

| Non-White | Ref | |

| White | −9.67 (4.97) | |

| Prior HTN | −3.54 (3.44) | 0.05 |

| Smoking History | 0.31 | |

| Never | Ref | |

| Former | −2.84 (3.21) | |

| Current | 0.57 (4.43) | |

| Prior Nephrectomy | −9.01 (3.88) | 0.30 |

| Risk Group | 0.61 | |

| Favorable | Ref | |

| Intermediate | 5.11 (3.6) | |

| Poor | 8.38 (6.6) |

abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HTN = hypertension; Ref = reference group; SE = standard error; VEGFR-TKI = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

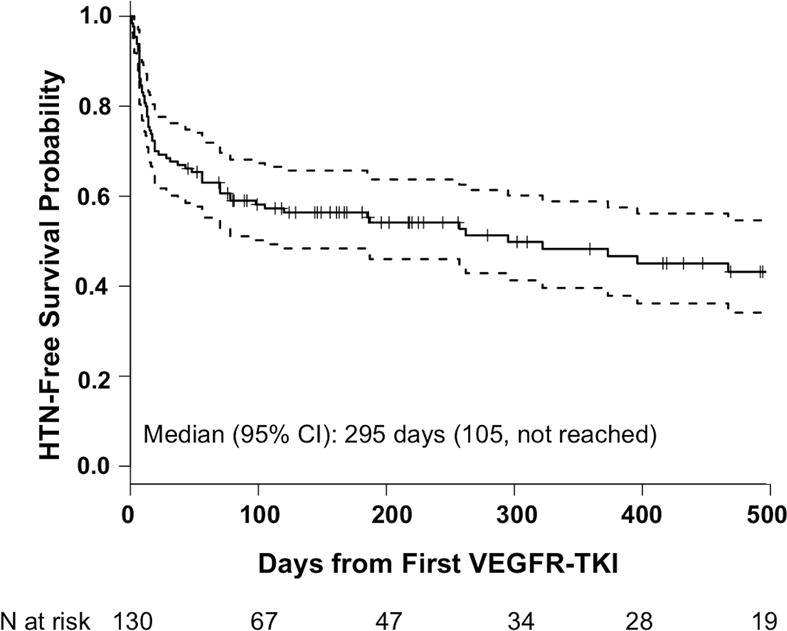

New/worsening HTN developed in 65 patients over follow-up (Figure 2). Mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) at the time when anti-HTN regimen was first started or changed was 153.4 mmHg (SD 16.3) and mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was 89.9 mmHg (SD 9.8). Mean SBP at the time of last follow up or discontinuation of the VEGFR-TKI was 130.0 mmHg (SD 16.3) and mean DBP was 80.1 mmHg (SD 8.5). Median time to development of new/worsening HTN was 0.8 years (95% CI: 0.3 – not reached), and median follow-up time among those who did not develop new/worsening HTN was 0.7 years (min=0.1, max=5.2). Overall, development of new/worsening HTN occurred within 30 days from first VEGFR-TKI use in 41 patients (31.5%). The proportion of patients who developed new/worsening HTN within 30 days of first VEGFR-TKI was similar in those with abnormal and normal eGFR (32% vs. 31%, respectively, P=0.91). To control blood pressure (BP), 54% of the patients were started on calcium channel blockers or had its dose increased. Further, 19% of the patients were started on or had the dose increased of angiotensin receptor blockers or angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, and 8.8% of the patients were started on or had the dose increase of the beta blocker. The rest were treated with either thiazide diuretics or combinations of the above medications.

Figure 2.

The solid line represents probability of remaining free of new/worsening HTN and the dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval. During follow-up, 65 patients (50%) developed new/worsening HTN at any time. Median follow-up time among those who did not develop new/worsening HTN was 244 days (min=45 days, max=1916 days). CI = confidence interval; HTN = hypertension; VEGFR-TKI = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

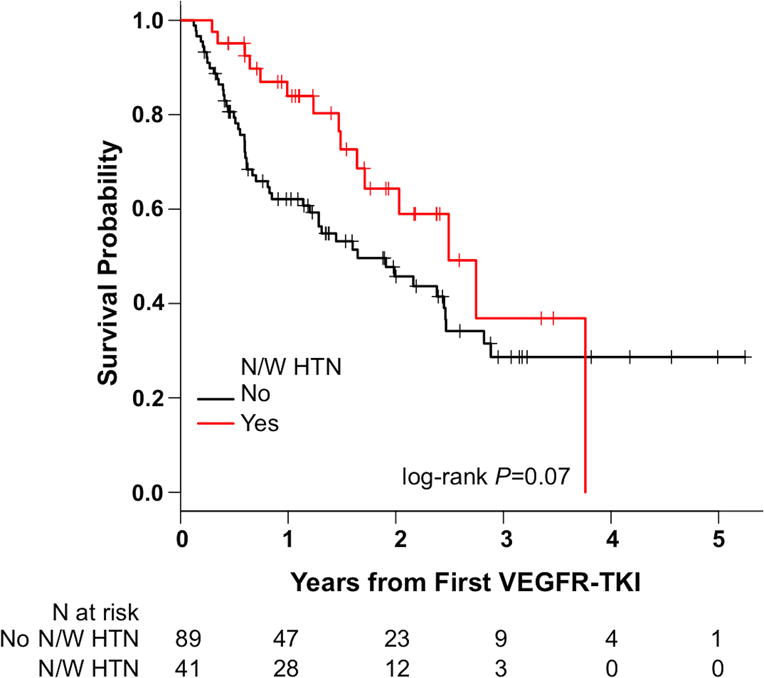

Using mixed effects model analysis starting 30 days after initiation of treatment, we found that developing new/worsening HTN had little effect on eGFR. There was no significant association between the development of new/worsening HTN within 30 days and eGFR (P=0.41). Additionally, there was no significant interaction between days from first VEGFR-TKI and new/worsening HTN within 30 days (P=0.38). Due to growing evidence supporting the development of HTN as a biomarker of VEGFR-TKI efficacy,17 we examined the association between new/worsening HTN within the first 30 days and OS. In our patients, those who developed new/worsening HTN within 30 days appeared to have a slight survival advantage over the group that did not, but this was not found to be statistically significant (P=0.07, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

There was no significant difference in overall survival between those who developed new/worsening HTN by 30 days after first VEGFR-TKI and those who did not (P = 0.07). N/W HTN = new or worsening hypertension; VEGFR-TKI = vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

DISCUSSION

In this study of patients with mRCC who were treated with VEGFR-TKIs, abnormal baseline eGFR, older age, and higher BMI were significantly associated with lower eGFR over time. We found that there was an upward trend in eGFR over follow-up and that there was no significant difference in eGFR trends when comparing patients with abnormal baseline renal function to those with normal baseline renal function. We also found that half of all patients developed new/worsening HTN during follow up, and that most of these patients did so within the first 30 days. Regarding OS, we saw that those with abnormal baseline eGFR appeared to have a survival advantage that did not hold statistical significance after adjusting for other baseline factors. Those who developed new/worsening HTN within 30 days of follow up also appeared to survive longer, but this did not reach statistical significance either.

Our findings suggest that the renal function of our patients is stable overall, despite the known age-related decline in GFR of 0.75–1 ml/min per 1.73 m2 every year after 40 years of age.21 However, few studies have looked specifically at glomerular filtration in patients on anti-VEGF therapies. One study examined mRCC patients treated with VEGFR-TKIs following unilateral nephrectomy and found an overall decline in GFR of 1.23–2.51 ml/min per 1.73 m2 each year, depending on the method used for analysis.22 Without a group for comparison it was not possible to distinguish this from physiologic decline. Additionally, most VEGFR-TKI trials exclude patients with abnormal kidney function; therefore, the outcomes of these patients while on VEGFR-TKIs have not been well reported. In one analysis of clinical trials of sunitinib and sorafenib, it was found that among 21 patients with renal insufficiency prior to the start of treatment, the median difference between baseline creatinine clearance and the lowest creatinine clearance was 2.2 ml/min per 1.73 m2 over a median treatment duration of 8.7 months.23 These findings and ours do not suggest that there is a significant decline in the renal function of these patients while being treated with VEGFR-TKIs, even in the presence of underlying kidney disease.

The trend toward a survival advantage demonstrated by patients with abnormally low baseline eGFR is an unpredicted result, though it is likely explained by other baseline differences between the two groups, as this association is no longer significant in multivariable analysis. For example, the groups differed significantly in the proportion of patients who underwent nephrectomy prior to the start of treatment, with nephrectomies being more common in those with low baseline eGFR. A vast majority of these nephrectomies were radical, which are associated with lower postoperative GFR and increased risk of new-onset CKD.24,25 Additionally, prior nephrectomy itself is a prognostic indicator described by Motzer et al,19 and may contribute to the survival advantage. Although a few patients underwent nephrectomy after starting VEGFR-TKIs, most of those who did not undergo prior nephrectomy were not deemed to be good candidates. The reasons cited for this included patient comorbidities, high burden of metastatic disease, and low likelihood of achieving clinical benefit. Therefore, those who undergo nephrectomies may be more likely to have both a lower eGFR and also a better prognosis.

In our patients, those who developed new/worsening HTN appeared to have a survival advantage over the group that did not, but this association did not reach statistical significance. It is worth noting that several of the studies cited as evidence for HTN as a potential biomarker for efficacy show clinical benefit (e.g. in progression-free survival) with no statistically significant difference in OS.26–28 If a difference in OS indeed exists, the ability to detect one in our study could have been limited by our sample size as well as the retrospective nature of the study. An ongoing trial on axitinib escalation aims to provide more definitive evidence on whether HTN is a valid biomarker of efficacy (NCT00835978). Preliminary data from this study indicates that patients in the axitinib titration group achieved greater objective response.29

Overall, development of new/worsening HTN did not have an effect on eGFR. This is most likely due to the fact that BP was well controlled with mean SBP and DBP within normal limits at last follow up or at discontinuation of therapy and relatively short duration of follow up.

Our study design was not without limitations. While patients were often encouraged to monitor their BPs at home, decisions on adding or increasing medications (i.e. our criteria for new/worsening HTN) were also made based on measurements in the clinic. Neither of these methods may capture changes in BP as reliably as 24-hour ambulatory monitoring.30 Additionally, for the purpose of this study, there was no defined elevation in BP reading for which an increase or change in medications should be prescribed. However, the general practice in our institution is to follow recommendations from Angiogenesis Task Force of National Cancer Institute which recommended initiation or adjustment of antihypertensive regimen for BP >140/90 or more than 20 mm Hg change in DBP.18 Most of our analysis does not account for breaks in treatment, which ranged in length from days to months and for a variety of reasons including adverse events as well as treatment with agents that do not target the VEGF pathway. However, we found that cumulative treatment days were similar between groups. The retrospective nature of our study and lack of a control group prevents us from finding any definitively causative associations, making the interpretation of trends in eGFR less clear. Another limitation was the use of serum creatinine to calculate eGFR as a measurement of renal function, which may explain the upward trend in eGFR in our patients. Serum creatinine may have decreased due to progressive cachexia and loss of muscle mass in these cancer patients, rather than an improvement in renal function. In this study we were unable to assess proteinuria as this data is not routinely collected. We had post-VEGFR-TKI proteinuria data for only 79/130 (60.8%) of the patients included in the study, and among those patients, only 6 (7.1%) had clinically significant proteinuria. This should be investigated more rigorously in future studies.

PERSPECTIVES

In summary, our study finds no obvious differences in the effect of VEGFR-TKIs on renal function for those with abnormal renal function versus those with normal renal function at baseline. Additionally, our study demonstrates that the development of new/worsening HTN has no significant impact on OS or association with progressive decline in renal function. These findings suggest that these drugs can be used in patients with renal insufficiency or new onset HTN without any additional risk of further kidney dysfunction. However, prospective long-term studies will be needed to better assess the effects of VEGFR-TKIs on long-term renal function.

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is New?

This study characterized the effects of hypertension on renal function in patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors for kidney cancer.

This study demonstrates that new development of hypertension or worsening hypertension does not have a significantly adverse effect on renal function in patients treated for kidney cancer.

What Is Relevant?

Hypertension induced by the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors is not linked to worse renal function outcomes in patients with kidney cancer.

Summary

Hypertension is common as result of use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Even in subjects with abnormal renal function at baseline the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors did not have a significant effect on renal function.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

These studies were funded by a Byrne Research Fund at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (EAJ) and NIH National Cancer Institute Center Grant P30 CA008748. The funders had no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing this report; or in the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Contributions: Research idea and study design: IGG, EAJ; data acquisition: BCB; data analysis/interpretation: BCB, ECZ, EAJ; statistical analysis: ECZ; supervision or mentorship: IGG, EAJ. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. BCB takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

DISCLOSURES

BCB: None

ECZ: None

IGG: Owns stock in Pfizer, Inc. No other disclosures.

EAJ: None

References

- 1.Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, Russell MW, Charbonneau C. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): A literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet. 373:1119–1132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabinovitch RA, Zelefsky MJ, Gaynor JJ, Fuks Z. Patterns of failure following surgical resection of renal cell carcinoma: implications for adjuvant local and systemic therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:206–212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.1.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fergany AF, Hafez KS, Novick AC. Long-term results of nephron sparing surgery for localized renal cell carcinoma: 10-year followup. J Urol. 2000;163:442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motzer RJ, Bander NH, Nanus DM. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:865–875. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609193351207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim WY, Kaelin WG. Role of VHL Gene Mutation in Human Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4991–5004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iliopoulos O, Levy AP, Jiang C, Kaelin WG, Goldberg MA. Negative regulation of hypoxia-inducible genes by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10595–10599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eremina V, Jefferson JA, Kowalewska J, Hochster H, Haas M, Weisstuch J, Richardson C, Kopp JB, Kabir MG, Backx PH, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Barisoni L, Alpers CE, Quaggin SE. VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic Microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1129–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster RR, Hole R, Anderson K, Satchell SC, Coward RJ, Mathieson PW, Gillatt DA, Saleem MA, Bates DO, Harper SJ. Functional evidence that vascular endothelial growth factor may act as an autocrine factor on human podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F1263–F1273. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00276.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horowitz JR, Silver M, Tsurumi Y, Chen D, Sullivan A, Isner JM. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor produces nitric oxide–dependent hypotension: evidence for a maintenance role in quiescent adult endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2793–2800. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hood JD, Meininger CJ, Ziche M, Granger HJ. VEGF upregulates ecNOS message, protein, and NO production in human endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;274:H1054–H1058. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.3.H1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Izzedine H, Rixe O, Billemont B, Baumelou A, Deray G. Angiogenesis inhibitor therapies: focus on kidney toxicity and hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:203–218. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frangié C, Lefaucheur C, Medioni J, Jacquot C, Hill GS, Nochy D. Renal thrombotic microangiopathy caused by anti-VEGF-antibody treatment for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:177–178. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roncone D, Satoskar A, Nadasdy T, Monk JP, Rovin BH. Proteinuria in a patient receiving anti-VEGF therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Neph. 2007;3:287–293. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi D, Nagahama K, Tsuura Y, Tanaka H, Tamura T. Sunitinib-induced nephrotic syndrome and irreversible renal dysfunction. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2011;16:310–315. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson ES, Khankin EV, Karumanchi SA, Humphreys BD. Hypertension induced by vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway inhibition: mechanisms and potential use as a biomarker. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maitland ML, Bakris GL, Black HR, Chen HX, Durand JB, Elliott WJ, Ivy SP, Leier CV, Lindenfeld J, Liu G, Remick SC, Steingart R, Tang WH. Initial assessment, surveillance, and management of blood pressure in patients receiving vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:596–604. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, Berg W, Amsterdam A, Ferrara J. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2530–2530. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2012;379:165–180. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Launay-Vacher V, Ayllon J, Janus N, Medioni J, Deray G, Isnard-Bagnis C, Oudard S. Evolution of renal function in patients treated with antiangiogenics after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol-Semin Ori. 2011;29:492–494. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan G, Golshayan A, Elson P, Wood L, Garcia J, Bukowski R, Rini B. Sunitinib and sorafenib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients with renal insufficiency. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1618–1622. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mariusdottir E, Jonsson E, Marteinsson VT, Sigurdsson MI, Gudbjartsson T. Kidney function following partial or radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: a population-based study. Scand J Urol. 2013;47:476–482. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2013.783624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, Snyder M, Vickers AJ, Raj GV, Scardino PT, Russo P. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:735–740. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70803-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scartozzi M, Galizia E, Chiorrini S, Giampieri R, Berardi R, Pierantoni C, Cascinu S. Arterial hypertension correlates with clinical outcome in colorectal cancer patients treated with first-line bevacizumab. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:227–230. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bono P, Elfving H, Utriainen T, Osterlund P, Saarto T, Alanko T, Joensuu H. Hypertension and clinical benefit of bevacizumab in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:393–394. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravaud A, Sire M. Arterial hypertension and clinical benefit of sunitinib, sorafenib and bevacizumab in first and second-line treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:966–967. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rini BI, Melichar B, Ueda T, Grünwald V, Fishman MN, Arranz JA, Bair AH, Pithavala YK, Andrews GI, Pavlov D, Kim S, Jonasch E. Axitinib with or without dose titration for first-line metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised double-blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70464-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verdecchia P, Porcellati C, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Battistelli M, Guerrieri M, Gatteschi C, Zampi I, Santucci A, Santucci C, Reboldi G. Ambulatory blood pressure. An independent predictor of prognosis in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1994;24:793–801. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.24.6.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]