Abstract

The dynamics of the diffuse interface between liquid and solid states is analysed. The diffuse interface is considered as an envelope of atomic density amplitudes as predicted by the phase-field crystal model (Elder et al. 2004 Phys. Rev. E

70, 051605 (doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.70.051605); Elder et al. 2007 Phys. Rev. B

75, 064107 (doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.75.064107)). The propagation of crystalline amplitudes into metastable liquid is described by the hyperbolic equation of an extended Allen–Cahn type (Galenko & Jou 2005 Phys. Rev. E

71, 046125 (doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.71.046125)) for which the complete set of analytical travelling-wave solutions is obtained by the  method (Malfliet & Hereman 1996 Phys. Scr.

15, 563–568 (doi:10.1088/0031-8949/54/6/003); Wazwaz 2004 Appl. Math. Comput.

154, 713–723 (doi:10.1016/S0096-3003(03)00745-8)). The general

method (Malfliet & Hereman 1996 Phys. Scr.

15, 563–568 (doi:10.1088/0031-8949/54/6/003); Wazwaz 2004 Appl. Math. Comput.

154, 713–723 (doi:10.1016/S0096-3003(03)00745-8)). The general  solution of travelling waves is based on the function of hyperbolic tangent. Together with its set of particular solutions, the general

solution of travelling waves is based on the function of hyperbolic tangent. Together with its set of particular solutions, the general  solution is analysed within an example of specific task about the crystal front invading metastable liquid (Galenko et al. 2015 Phys. D

308, 1–10 (doi:10.1016/j.physd.2015.06.002)). The influence of the driving force on the phase-field profile, amplitude velocity and correlation length is investigated for various relaxation times of the gradient flow.

solution is analysed within an example of specific task about the crystal front invading metastable liquid (Galenko et al. 2015 Phys. D

308, 1–10 (doi:10.1016/j.physd.2015.06.002)). The influence of the driving force on the phase-field profile, amplitude velocity and correlation length is investigated for various relaxation times of the gradient flow.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘From atomistic interfaces to dendritic patterns’.

Keywords: crystal–liquid interface, phase-field crystals, atomic density, partial differential equations, gradient flow, travelling wave solution

1. Introduction

The phase-field crystal (PFC) model has been used to examine the dynamics of liquid–solid transformation, grain boundary migration and dislocation motion [1–3]. The PFC model is a continuum model that describes processes on atomic length scales and pattern on the nano- and micro-length scales [4]. This model is characterized by a free energy which is represented by a functional of a conserved atomic density field that is periodic in the solid phase and uniform in a liquid state. One of the simplest ways to analyse the PFC model is to use the amplitude equations [5–7] which represent smooth profiles over peaks of the density field (see a short discussion about obtaining the amplitude equation of the PFC equation in appendix A). Taking into account slow and fast degrees of freedom for the crystal–liquid interface propagation, the amplitude equation of the PFC model is described by the following partial differential equation (PDE) [8]:

| 1.1 |

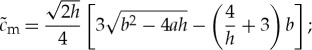

The following notations are introduced in equation (1.1): u(r,t) is the amplitude of atomic density (order parameter), τ is the time for relaxation of the rate ∂u/∂t, i.e. the gradient flow (τ has a real value smaller than the relaxation time of the amplitude u as defined in [8]), r is the radius vector, t is the time, and the parameter b is given by

| 1.2 |

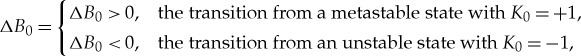

where the driving force ΔB0 describes

|

1.3 |

a and v are the coefficients in the free energy, which has the form of Landau–de Gennes potential:

| 1.4 |

As it follows from equation (1.4), the two states (liquid and solid) have equal energy in the equilibrium with the parameter b=8a2/135v and the crystalline front has zero velocity.

Equation (1.1) can be considered as an extended Cahn–Allen equation which transforms to its standard form at b=0 and τ=0 [9], which was suggested for the anti-phase boundary motion and then used in a wide spectrum of mathematical and physical applications [10], for instance, in description of free-boundary problems by the phase-field method [4]. In its complete form, equation (1.1) has been applied in the field of fast-phase transitions [11,12] whose validity has been verified by comparison with experimental data [13], in molecular dynamics simulations [14] and by coarse-graining derivations of the phase-field equations [15].

PDE can be analysed using an important class of travelling-wave solutions which, in their particular form, include  functions [16,17]. Particular solutions of equation (1.1) have also been found in the form of

functions [16,17]. Particular solutions of equation (1.1) have also been found in the form of  function [8]. However, there exists no general set of travelling waves for the hyperbolic equation of Allen–Cahn type (1.1). Therefore, the main purpose of the present work is to find a complete set of travelling waves for equation (1.1). This set will be found using the

function [8]. However, there exists no general set of travelling waves for the hyperbolic equation of Allen–Cahn type (1.1). Therefore, the main purpose of the present work is to find a complete set of travelling waves for equation (1.1). This set will be found using the  method [16–19] representing one of the ways of searching for solutions of travelling waves (as one of the applications of this method to physically relevant tasks, one can mention the work of Kourakis et al. [20]). The complete set of solutions will be checked on the existence of

method [16–19] representing one of the ways of searching for solutions of travelling waves (as one of the applications of this method to physically relevant tasks, one can mention the work of Kourakis et al. [20]). The complete set of solutions will be checked on the existence of  functions.

functions.

2. Travelling waves by the  method

method

One of the important solutions for the analysis of phase transformations is related to travelling waves [8,10,16–19,21]. To treat the nonlinear PDEs, the travelling waves are obtained by the first integral method [21–24] (which can be considered as one of particular cases of the direct method [25], generalizing the use of equivalent methods of finding the exact solutions of PDE, which were reduced to ODE [26]), and also using the G′/G-expansion method [27,28], the rank analytical technique [29] and phase-plane analysis [30,31].

In this work, we use the  method as a useful tool for the computation of the exact travelling waves by introducing a power series in

method as a useful tool for the computation of the exact travelling waves by introducing a power series in  function (function of hyperbolic tangent). The efficiency of the

function (function of hyperbolic tangent). The efficiency of the  method has been illustrated in [16–19] by applying it for a variety of selected equations, such as nonlinear equations of the Fischer type and the generalized Korteveg–de-Vries equation. Moreover, its modification, the

method has been illustrated in [16–19] by applying it for a variety of selected equations, such as nonlinear equations of the Fischer type and the generalized Korteveg–de-Vries equation. Moreover, its modification, the  method [19,32], is used to derive the solitons and kink solutions for some of the well-known nonlinear parabolic partial differential equations (the Newell–Whitehead, Fitz–Hugh–Nagumo and Burgers–Fisher equations). The

method [19,32], is used to derive the solitons and kink solutions for some of the well-known nonlinear parabolic partial differential equations (the Newell–Whitehead, Fitz–Hugh–Nagumo and Burgers–Fisher equations). The  method extends a set of the possible solutions and provides abundant solitons and kink solutions in addition to the existing ones. As a result, the power of the

method extends a set of the possible solutions and provides abundant solitons and kink solutions in addition to the existing ones. As a result, the power of the  method is confirmed as the most direct and effective algebraic methods [32,33] for finding the exact solutions of nonlinear differential equations.

method is confirmed as the most direct and effective algebraic methods [32,33] for finding the exact solutions of nonlinear differential equations.

Let us consider spatially one-dimensional equation (1.1) for the atomic density amplitude u(x,t), which is evolving in time t along spatial coordinate x. Following Malfliet & Hereman [16] as well as Wazwaz [19], we introduce a new independent variable

| 2.1 |

which describes propagation of the amplitude with the velocity c and transforms the amplitude u(x,t)→U(ξ). This transformation rewrites the derivatives as follows:

| 2.2 |

Using derivatives from equation (2.2), spatially one-dimensional equation (1.1) in the new variable looks like

| 2.3 |

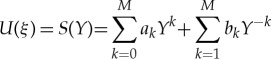

To solve equation (2.3), we shall apply the  method [16,17], introducing the finite expansion

method [16,17], introducing the finite expansion

|

2.4 |

and

| 2.5 |

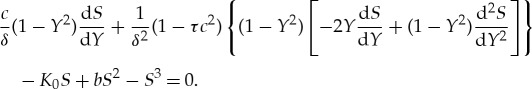

Using the new variable by equation (2.5) and taking into account the derivatives d/dξ=(1−Y 2) d/dY , d2/dξ2=(1−Y 2)[−2Y d/dY +(1−Y 2) d2/dY 2], equation (2.3) is described by

|

2.6 |

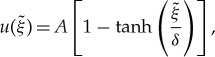

The parameter M from equation (2.4) can be determined using the analysis given in [16,17]. Indeed, balancing the linear terms of the highest order with the highest order nonlinear terms in equation (2.6), one can get 3M=4+M−2; therefore, M=1. Balancing the linear terms of the highest order in equation (2.6), one obtains M=1, so the expansion (2.4) becomes

| 2.7 |

with the following derivatives:

|

2.8 |

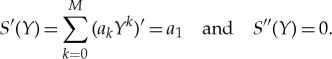

Now, using equations (2.7) and (2.8), we collect the coefficients of powers of Y n in equation (2.3) as

|

2.9 |

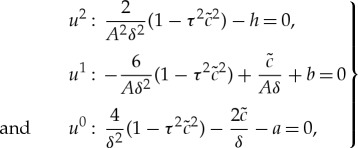

Equation (2.9) has a solution if the braces ahead of Y k are placed to zero. As such, the following system of equations regarding the parameters ak (k=0 … M), c and δ is obtained:

| 2.10 |

| 2.11 |

| 2.12 |

| 2.13 |

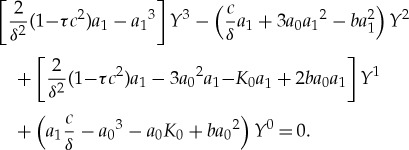

The system of equations (2.10)–(2.13) has a trivial solution a1=0 and  with the arbitrary values of c and δ. In this case, the amplitude has constant profile u(x,t)=a0. This homogeneous solution has no interest for us because we are looking for the inhomogeneous amplitude’s profiles of atomic density, which are moving through the metastable/unstable homogeneous state (liquid phase). In the case a1≠0, equations (2.10)–(2.13) look like

with the arbitrary values of c and δ. In this case, the amplitude has constant profile u(x,t)=a0. This homogeneous solution has no interest for us because we are looking for the inhomogeneous amplitude’s profiles of atomic density, which are moving through the metastable/unstable homogeneous state (liquid phase). In the case a1≠0, equations (2.10)–(2.13) look like

| 2.14 |

| 2.15 |

| 2.16 |

| 2.17 |

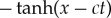

Equations (2.14)–(2.17) imply several analytical constraints. First, the reality of a1 in equation (2.14) imposes the condition: 1−τc2>0, which gives an upper bound in the absolute value of the amplitude’s velocity c (i.e.  and

and  with τ→0). Second, recalling that the sign of a1 determines the polarity of the amplitudes, we may assume that, for the propagation towards the positive direction on the x-axis, c>0, one finds a1>0 for a0<b/3, and a1<0 for a0>b/3. Respectively, if the amplitude’s profile moves in the direction of negative values of x-axis, c<0, one finds a1>0 for a0>b/3 and a1<0. Furthermore, there is no solution (at least using the

with τ→0). Second, recalling that the sign of a1 determines the polarity of the amplitudes, we may assume that, for the propagation towards the positive direction on the x-axis, c>0, one finds a1>0 for a0<b/3, and a1<0 for a0>b/3. Respectively, if the amplitude’s profile moves in the direction of negative values of x-axis, c<0, one finds a1>0 for a0>b/3 and a1<0. Furthermore, there is no solution (at least using the  method) if a0=b/3. And, third, recall that, for c<0, one has

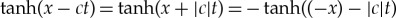

method) if a0=b/3. And, third, recall that, for c<0, one has  . Hence a negative value of c is physically tantamount to transformations: space reversal, x→−x; polarity reversal, a1→−a1; and velocity reversal, c→−c=|c|>0. In simple terms, propagation of the amplitude’s profile,

. Hence a negative value of c is physically tantamount to transformations: space reversal, x→−x; polarity reversal, a1→−a1; and velocity reversal, c→−c=|c|>0. In simple terms, propagation of the amplitude’s profile,  ), to the left is the same as propagation of the amplitude’s profile,

), to the left is the same as propagation of the amplitude’s profile,  , to the right.

, to the right.

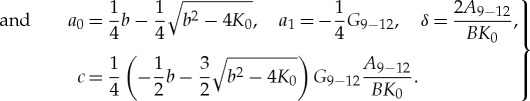

Determining the parameters a0, a1, δ and c from equations (2.14)–(2.17) leads to the amplitude profiles (2.4) and (2.5) of the form

| 2.18 |

Concrete values for a0, a1, δ and c present different types of solutions that are shown in the next two sections.

3. General set of solutions

A complete set of solutions consists of 12 decisions for the parameters K0 and b which are defined by equations (1.2) and (1.3). This number of decisions follows from the degrees of equations (2.14)–(2.17), where equation (2.14) and equation (2.16) assume two roots for each expression (four roots in total), multiplied by three decisions from the cubic equation (2.17). These 12 decisions can be divided into three sets, each one of which contains four similar by notation type of solutions. All coefficients from equation (2.18) are obtained for the following far field boundary conditions,  : u≡const., namely for u=0 or u=±1.

: u≡const., namely for u=0 or u=±1.

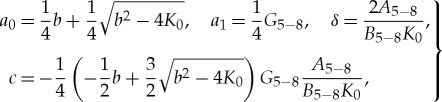

(a). Set of solutions 1–4

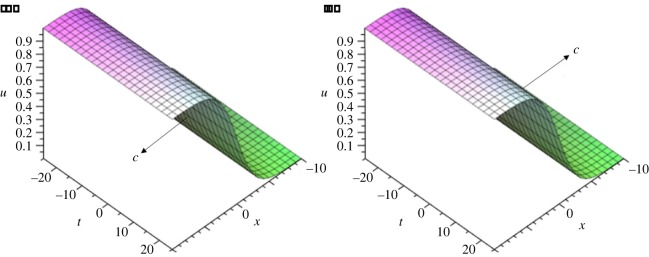

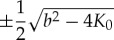

The first set of solutions can be recognized by the signs of the parameters a1 and c. As a result, solutions 1–4 are presented in table 1, two of which are shown in figure 1.

Table 1.

First set: solutions 1–4.

| values | solutions 1 and 2 | solutions 3 and 4 |

|---|---|---|

| a0 | b/2 | b/2 |

| a1 |  |

|

| δ |  |

|

| c |  |

|

Figure 1.

u-Profiles as functions of the spatial coordinate x and the time t calculated with the usage of solutions 3 and 4 from table 1. Calculations were carried out for fixed relaxation time τ=0.5 and for the values of a0, a1 and δ given by K0=1 and under the condition of b2≥4K0 (table 1). (a) u-profile moves in the direction of the x-axis with constant positive velocity c. (b) u-profile moves in the direction of the x-axis with constant negative velocity c.

With b=0 and K0=−1, table 1 shows that a0=0, a1=±1,  and c=0. In this particular case, equation (2.18) predicts stationary profiles:

and c=0. In this particular case, equation (2.18) predicts stationary profiles:

| 3.1 |

This profile is consistent with the steady solution of the hyperbolic Allen–Cahn equation (τ≠0) and the parabolic Allen–Cahn equation (τ=0), which are obtained from equation (1.1) for the above accepted parameters b=0 and K0=−1.

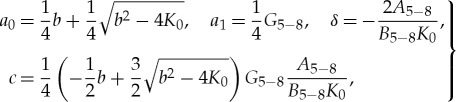

(b). Set of solutions 5–8

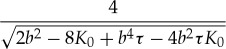

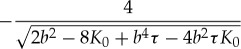

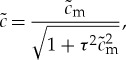

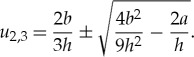

The second set of solutions, consisting of solutions 5–8, has a similar structure to that of the set of solutions 1–4. To simplify the representation, we shall introduce the following notations for these solutions:

|

3.2 |

| 3.3 |

| 3.4 |

Now, using equations (3.2)–(3.4), we rewrite solutions 5–8 in new designations:

|

3.5 |

|

3.6 |

|

3.7 |

|

3.8 |

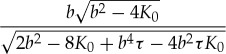

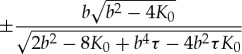

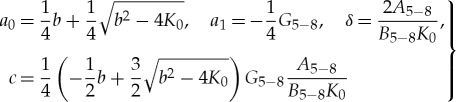

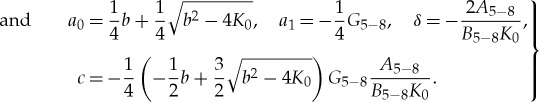

(c). Set of solutions 9–12

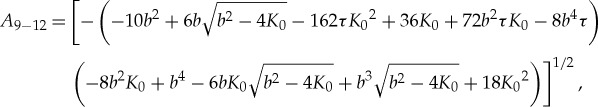

The third set, consisting of solutions 9–12, has a similar structure to that of the sets of solutions 1–4 and solutions 5–8. Introducing the parameters

|

3.9 |

| 3.10 |

| 3.11 |

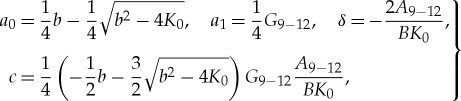

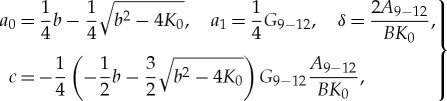

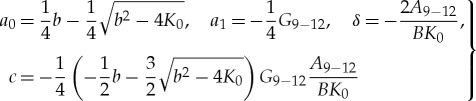

we finally rewrite parameters a0, a1, δ and c (given previously for solutions 5–8) as

|

3.12 |

|

3.13 |

|

3.14 |

|

3.15 |

4. Set of particular solutions

For the amplitude’s equation (2.3) the whole set of 12 solutions of the form of equation (2.18) is presented by the coefficients summarized in table 1, equations (3.5)–(3.8) and equations (3.12)–(3.15). Now, we compare special and particular cases of these solutions with corresponding results obtained earlier.

Using the first integral method [21], travelling wave solutions have been obtained for the hyperbolic Allen–Cahn equation [22]. This equation is consistent with equation (1.1) if b=0 and K0=−1. Indeed, if we substitute these values for b and K0 into solutions (3.5)–(3.8), then solutions of the form (2.18) correspond to those ones obtained in [22]. The graphical representation for this particular case is shown in figure 1, which gives a view for the atomic density profile that invades the homogeneous phase with positive and negative values of c. Another pair of solutions related to this particular case could be obtained for a0=a1=±0.5. Thus, in general, we have obtained four bounded solutions, which correspond to four bounded solutions of Nizovtseva et al. [22]. It should be noted that in [22] other four unbounded solutions were obtained. These solutions were extracted from the general set of solutions due to its physical and mathematical insolvency, namely, due to the absence of their physical meaning and the violation of the initial statement of the mathematical problem. In this work, we do not obtain the unbounded solutions because the  method states solutions (2.4)–(2.5) on the bounded set a priori: the solution (2.18) is always mathematically bounded.

method states solutions (2.4)–(2.5) on the bounded set a priori: the solution (2.18) is always mathematically bounded.

With zero relaxation time, τ=0, the hyperbolic equation (1.1) transforms to the partial differential equation of parabolic type whose travelling-wave solution has been previously found by Wazwaz [19]. Indeed, as it follows from our solutions (3.12)–(3.15), if we use τ=0 and take into account (3.9)–(3.11), solutions of Wazwaz [19] are covered for the extended Allen–Cahn equation.

In general, we have obtained travelling wave solutions represented by hyperbolic  functions (2.18), which confirms the correctness of the particular solutions for the dynamical problem of fast diffuse interfaces [34].

functions (2.18), which confirms the correctness of the particular solutions for the dynamical problem of fast diffuse interfaces [34].

5. Travelling waves in amplitudes of phase-field crystals

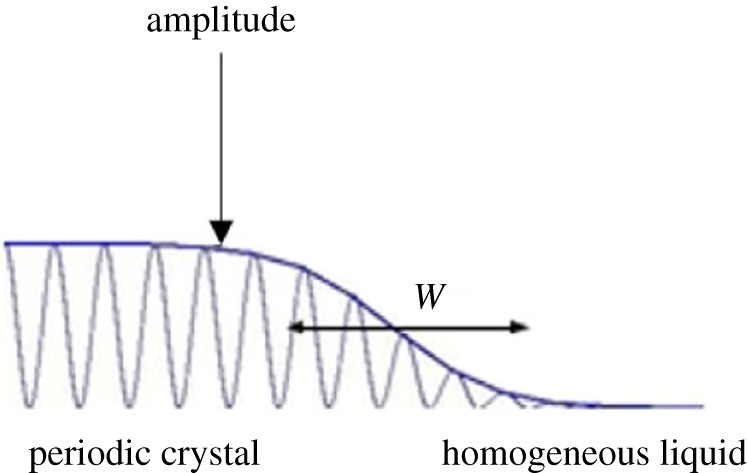

To demonstrate the applicability of the general solution (2.18) together with its set of concrete and particular solutions summarized in §§3 and 4, let us consider the dynamics of the diffuse crystal–liquid interface propagation as described by the PFC model [4]. In this model, investigation of the dynamics of periodic pattern propagation plays an important role [4]. Figure 2 presents a scheme for spatial distribution of the atomic density field near a solid–liquid interface, where peaks correspond to average atomic positions. The envelope of these peaks is described by the PFC amplitude’s equation and is consistent with the phase-field profile shown in figure 1. The interface width W in figure 2 represents the transition region between the atomically homogeneous state (liquid phase) and periodic states (crystal phase), i.e. the diffuse crystal–liquid interface.

Figure 2.

Diffuse front of a periodic crystal invading homogeneous liquid. Crystal and liquid are divided by the diffuse transitive layer of the width W. The amplitude represents the envelope of atomic density peaks.

(a). Analytical solution

The PFC amplitude’s equations were derived in [6–8]. In this work, we use the PFC amplitude’s equation in accordance with the work of Humadi et al. [35]:

| 5.1 |

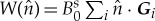

where u is the amplitude’s profile, τ is the relaxation time of the rate ∂u/∂t of change of the amplitude u (i.e. ∂u/∂t is the gradient flow) and  is the measure of the width of the diffuse transitive layer having the local normal vector

is the measure of the width of the diffuse transitive layer having the local normal vector  and the reciprocal lattice vector Ghkl with Miller indexes h, k and l.

and the reciprocal lattice vector Ghkl with Miller indexes h, k and l.

In equation (5.1), the free energy density f(u) is expressed by

| 5.2 |

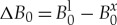

where

| 5.3 |

Here, cc is the concentration of a solute in a chemically binary system.1 Upper indexes l and s are related to the liquid and solid phases, respectively. Lower indexes 0 and 2 are related to the coefficients of the zero and second order; and r and  are the coefficients corresponding to u3 and u4, respectively. The driving force,

are the coefficients corresponding to u3 and u4, respectively. The driving force,  , is the difference between the dimensionless liquid compressibility Bl0 and the dimensionless elastic module

, is the difference between the dimensionless liquid compressibility Bl0 and the dimensionless elastic module  . In equilibrium at

. In equilibrium at  , the elasticity compensates the compressibility, that is

, the elasticity compensates the compressibility, that is  .

.

The free energy (5.2) has the form of the Landau–de Gennes potential, which has been used in the theory of weak crystallization [36] as well as in the PFC model [4]. This potential describes various states, which exist for possible transformations from metastable to stable or from unstable to stable states. In the present derivation, we shall use the configuration of states consistently with the transition from metastable liquid to stable crystal such that ΔB0>0 (see, for details, [8]). Finally, the free energy (5.1) corresponds to equation (2.3), and the free energy density (5.2) of Humadi et al. [35] is equivalent to equation (1.4) for our general derivation of the equation set.

Introducing normalized velocity  and correlation length

and correlation length  , equation (5.1) transforms to

, equation (5.1) transforms to

| 5.4 |

We search for a solution of equation (5.4) for the condition  (i.e. for

(i.e. for  ). This condition means that the interface velocity

). This condition means that the interface velocity  cannot overcome and be larger than the maximum speed of disturbance propagation in the field of order parameter u [11,34].

cannot overcome and be larger than the maximum speed of disturbance propagation in the field of order parameter u [11,34].

Using the general solution (2.18), we find the particular solution of (5.4) in the following form:

|

5.5 |

with A the amplitude factor and δ the correlation length. In this case, the derivatives are

| 5.6 |

Then, equation (5.4) can be rewritten as

| 5.7 |

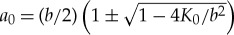

Equation (5.7) immediately gives the solution u=0, which describes the homogeneous state in a whole domain and has no interest for us. Then, opening the brackets and combining the u-terms with the same degree in equation (5.7), we obtain the following system of three equations:

|

5.8 |

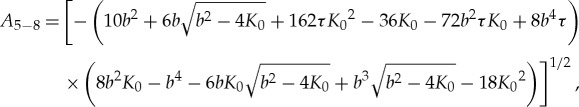

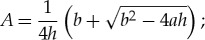

with three unknown parameters A, δ and  . As the result, the system of equations (5.8) gives

. As the result, the system of equations (5.8) gives

- — the solution for the positive amplitude factor A,

5.9 - — the solution for the diffuse interface velocity

,

,

with its maximum value

5.10  ,

,

5.11

In equations (5.9)–(5.12) we have the condition  .

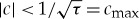

.

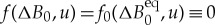

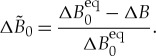

Finally, for the analysis of the dynamics of crystal front invading liquid by equations (5.5) and (5.9)–(5.12), we obtain now the driving force ΔB0 relative to its equilibrium value  which is chosen as a reference. From equation (5.2) it follows that the equilibrium state, having equal energy states, is defined by the equality

which is chosen as a reference. From equation (5.2) it follows that the equilibrium state, having equal energy states, is defined by the equality  . From this immediately follows the trivial solution u1=0, which again is of no interest to us as the homogeneous solution for a whole domain. For the other solutions under the condition of equal energy states, one can find

. From this immediately follows the trivial solution u1=0, which again is of no interest to us as the homogeneous solution for a whole domain. For the other solutions under the condition of equal energy states, one can find

|

5.13 |

In the equilibrium, u2=u3, the condition

| 5.14 |

should be satisfied. Using the parameter a from equation (5.3), the equilibrium value for the driving force is obtained as

| 5.15 |

As the result, for the further analysis and graphical interpretation of equations (5.5) and (5.9)–(5.12) we use the normalized driving force  :

:

|

5.16 |

(b). Numerical representation of analytical solutions

(i). Calculations

The amplitude front, i.e. the crystal–liquid boundary layer having a step-like profile, is a crystallization front invading the metastable liquid (figure 2). The travelling wave (5.5) serves to analyse the dynamics of the amplitude front. The profile of the amplitude front can be determined by three variables: (i) the amplitude factor A from equation (5.9), (ii) the velocity  from equations (5.10) and (5.11) with which the front moves, and (iii) the correlation length δ from equation (5.12). These variables depend on the driving force

from equations (5.10) and (5.11) with which the front moves, and (iii) the correlation length δ from equation (5.12). These variables depend on the driving force  given by equations (5.15) and (5.16) through the parameter a given by equation (5.3). In addition, the velocity

given by equations (5.15) and (5.16) through the parameter a given by equation (5.3). In addition, the velocity  and correlation length δ depend on the relaxation time τ of the gradient flow ∂u/∂t. Using calculation results, we show how the driving force and the relaxation parameter τ influence the profile of the amplitude density u, amplitude factor A, front velocity

and correlation length δ depend on the relaxation time τ of the gradient flow ∂u/∂t. Using calculation results, we show how the driving force and the relaxation parameter τ influence the profile of the amplitude density u, amplitude factor A, front velocity  and correlation length δ. The model parameters are used for the calculations as follows:

and correlation length δ. The model parameters are used for the calculations as follows:  , cc=0.1, r=4.25×10−10,

, cc=0.1, r=4.25×10−10,  and τ2=0.1. Note that the relaxation time τ has been taken as a constant value only for calculations of the amplitude density u and amplitude factor A. The front velocity

and τ2=0.1. Note that the relaxation time τ has been taken as a constant value only for calculations of the amplitude density u and amplitude factor A. The front velocity  and correlation length δ are shown for different values of τ (see next section).

and correlation length δ are shown for different values of τ (see next section).

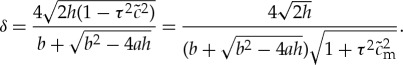

(ii). Influence of driving force and relaxation time

The influence of the driving force  on the phase-field profile is shown in figure 3, where the solution equation (5.5) with equations (5.9)–(5.12) exhibits a dynamical step-like profile for the atomic density amplitude. It is clearly seen from figure 3 that the increase of

on the phase-field profile is shown in figure 3, where the solution equation (5.5) with equations (5.9)–(5.12) exhibits a dynamical step-like profile for the atomic density amplitude. It is clearly seen from figure 3 that the increase of  makes the step-like profile within the diffuse interface between the crystal and the liquid steeper. Therefore, the gradient of atomic density has maximal values at a higher driving force in the transition from the diffuse to sharp interface.

makes the step-like profile within the diffuse interface between the crystal and the liquid steeper. Therefore, the gradient of atomic density has maximal values at a higher driving force in the transition from the diffuse to sharp interface.

Figure 3.

Amplitude of the atomic density as a function of the moving coordinate system according to equations (5.5) and (5.9)–(5.12).

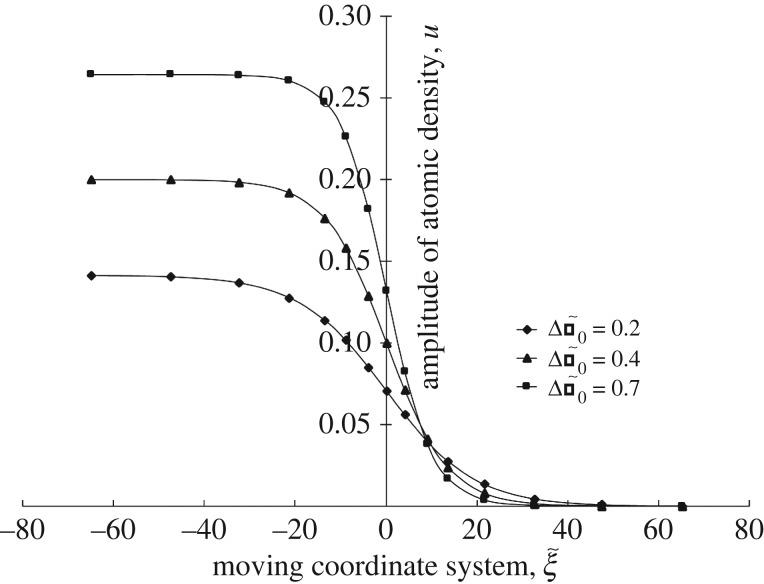

Figure 4 shows nonlinear dependence of the velocity for the amplitude’s profile. Such dependence is consistent with the data of numerical molecular dynamics simulation [37] and recent advancements on kinetics of fast interfaces [38]. As also follows from figure 4, the amplitude velocity  depends on the values of relaxation time τ. The difference between velocities for different τ occurs, however, at moderate and large values of driving forces, namely, at

depends on the values of relaxation time τ. The difference between velocities for different τ occurs, however, at moderate and large values of driving forces, namely, at  . At small

. At small  , the influence of relaxation time τ is negligible. Such dependence exists due to the fact that the time τ influences the relaxation of fast variable—gradient flow, ∂u/∂t—the variable which plays an essential role far from the equilibrium [11]. A general tendency is that a longer relaxation time τ makes the velocity increase slower. Indeed, the dynamics by the parabolic Allen–Cahn equation (see equation (1.1) with τ=0) is defined by the relaxation of the order parameter u only. The dynamics by the hyperbolic Allen–Cahn equation (1.1) is already defined by the relaxation of the order parameter u and by the gradient flow ∂u/∂t. As a result, in comparison with the parabolic dynamics, the additional relaxation in the hyperbolic dynamics makes the velocity

, the influence of relaxation time τ is negligible. Such dependence exists due to the fact that the time τ influences the relaxation of fast variable—gradient flow, ∂u/∂t—the variable which plays an essential role far from the equilibrium [11]. A general tendency is that a longer relaxation time τ makes the velocity increase slower. Indeed, the dynamics by the parabolic Allen–Cahn equation (see equation (1.1) with τ=0) is defined by the relaxation of the order parameter u only. The dynamics by the hyperbolic Allen–Cahn equation (1.1) is already defined by the relaxation of the order parameter u and by the gradient flow ∂u/∂t. As a result, in comparison with the parabolic dynamics, the additional relaxation in the hyperbolic dynamics makes the velocity  smaller with the increase in relaxation time τ for a given

smaller with the increase in relaxation time τ for a given  .

.

Figure 4.

Amplitude’s velocity as a function of the driving force according to equations (5.10) and (5.11).

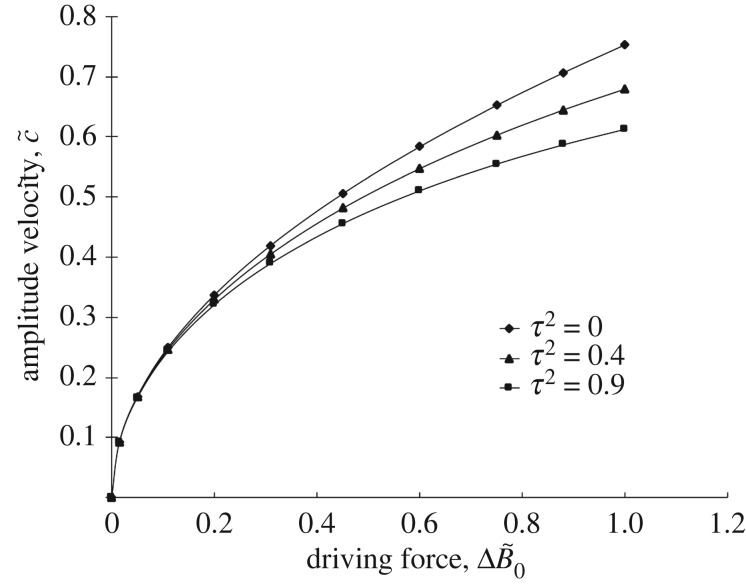

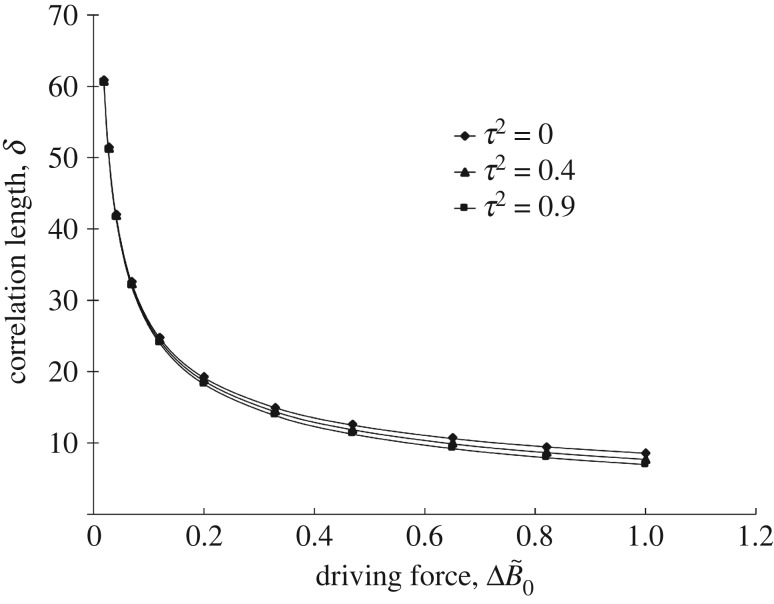

Dependence of correlation length δ on the driving force and relaxation time is shown in figure 5. The drastic change in δ occurs at smaller values of the driving force, namely, at  . Gradual decrease of δ to its minimal values occurs at moderate and large values of driving forces, i.e. at

. Gradual decrease of δ to its minimal values occurs at moderate and large values of driving forces, i.e. at  , showing that far from the equilibrium the interface becomes steeper, which directly follows from equation (5.12). It can also be seen from figure 5 that the larger relaxation time τ reduces the correlation length of the atomic density amplitude for

, showing that far from the equilibrium the interface becomes steeper, which directly follows from equation (5.12). It can also be seen from figure 5 that the larger relaxation time τ reduces the correlation length of the atomic density amplitude for  . Therefore, longer relaxation time τ at large driving force makes the interface steeper as a result of essential deviation from the equilibrium.

. Therefore, longer relaxation time τ at large driving force makes the interface steeper as a result of essential deviation from the equilibrium.

Figure 5.

Correlation length as a function of the driving force according to equation (5.12).

6. Conclusion

The propagation of amplitudes of the atomic density of crystals which invade a homogeneous liquid state has been analysed. Using the PFC model [4], amplitude equation (1.1) for the atomic density has been solved by application of the  method [16–19,32,33].

method [16–19,32,33].

A set of travelling wave solutions obtained on the basis of the general solution (2.18) are described by  functions. This confirms the correctness of the previously used particular solutions [34] used for fast transformations in materials. The set of solutions includes travelling waves previously found for (i) the extended parabolic Allen–Cahn equation [17] and (ii) the hyperbolic Allen–Cahn equation with a free energy of a double-well form which describes transitions from an unstable state [22].

functions. This confirms the correctness of the previously used particular solutions [34] used for fast transformations in materials. The set of solutions includes travelling waves previously found for (i) the extended parabolic Allen–Cahn equation [17] and (ii) the hyperbolic Allen–Cahn equation with a free energy of a double-well form which describes transitions from an unstable state [22].

The general  solution is analysed within a specific task of a crystal front invading metastable liquid. We have found spatial profiles of atomic density amplitude u, amplitude velocity

solution is analysed within a specific task of a crystal front invading metastable liquid. We have found spatial profiles of atomic density amplitude u, amplitude velocity  and correlation length δ as the functions in driving force

and correlation length δ as the functions in driving force  . We have shown that amplitude of atomic density decreases, velocity increases and correlation length drastically decreases with the increase of the driving force. It is also shown that a longer relaxation of the gradient flow makes the velocity increase with a slower driving force. Such results well agree with the particular travelling-wave solutions [8] and, therefore, solutions (5.5) and (5.9)–(5.12), which are graphically shown in figures 3–5, can be used as benchmarks for various numerical solutions of the PFC equation. Because periodic density fields play a crucial role in the formation of crystal lattices and dendrites [39], the present travelling-wave solutions can also be useful for the estimations of interface dynamics of dendritic patterns.

. We have shown that amplitude of atomic density decreases, velocity increases and correlation length drastically decreases with the increase of the driving force. It is also shown that a longer relaxation of the gradient flow makes the velocity increase with a slower driving force. Such results well agree with the particular travelling-wave solutions [8] and, therefore, solutions (5.5) and (5.9)–(5.12), which are graphically shown in figures 3–5, can be used as benchmarks for various numerical solutions of the PFC equation. Because periodic density fields play a crucial role in the formation of crystal lattices and dendrites [39], the present travelling-wave solutions can also be useful for the estimations of interface dynamics of dendritic patterns.

Appendix A. A couple remarks on amplitude equations

Amplitude equations (AEq) [7,8] of the regular PFC equation provide a description of envelopes of maxima of atomic density distribution in crystals having different symmetry (triangular, hexagonal, cubic symmetry, etc.). They appear as a result of a coarse-graining procedure providing transition from the nano-length periodic pattern (described by the regular PFC equation of the sixth order in space) to a monotonically smoothing mesoscale pattern (described by the AEq which already has the second order in space). This procedure is based on the renormalization group theory and was developed analytically by Goldenfeld et al. [5,6]. As a result of this procedure, one can formulate a physical meaning of the classical phase field as a non-conserved order parameter: the phase field is a smooth envelope of the atomic density maxima of a given crystalline symmetry. In this sense, properties of the phase field can be measured (in the form of its mobility, gradient factor and relaxation time) in natural or computational experiments.

Shiwa [40] established a discussion about the correctness of the Goldenfeld et al. analysis [5,6] applied to the PFC equation for obtaining the respective AEq. First, Shiwa has found a small analytical mistake in the AGD analysis, which does not influence the final result for AEq [41]. Second, Shiwa stressed the fact that the ADG analysis fails in the description of mode coupling. More specifically, because the PFC equation describes conserved dynamics, the amplitude of slow neutral modes at zero wavenumber should be coupled with the modes at the critical wavenumber behind which a homogeneous state becomes unstable. This second issue of zeroth mode for conserved dynamics has also been successfully resolved [42] in obtaining the AEq of the PFC equation.

For practical use of AEqs, it is important to know what they are missing compared with the regular PFC equation. In addition to losing mode coupling [40,42], the other problem is the lack of barriers between boundaries [43]. AEqs are also missing instantaneous mechanical equilibrium (as is the full PFC equation) [44]. To avoid these inconsistences arising in the transition from the regular PFC equation to its AEqs, a more complete approach up to all orders of multiple scale expansion can be used (see Sect. III of Huang et al. [45]).

Footnotes

Humadi et al. [35] derived the amplitude’s equation for u together with an additional equation for the concentration cc. They have solved this system of two equations under some approximations analytically and numerically. For the sake of simplicity, in this work, we assume the constant concentration, cc≡const., and find an exact analytical solution of equation (5.1).

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant no. 16-11-10095), Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (ID 1160779) and the German Space Center Space Management under contract no. 50WM1541.

References

- 1.Elder KR, Grant M. 2004. Modeling elastic and plastic deformations in nonequilibrium processing using phase field crystals. Phys. Rev. E 70, 051605 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.051605) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elder KR, Provatas N, Berry J, Stefanovich P, Grant M. 2007. Phase-field crystal modeling and classical density functional theory of freezing. Phys. Rev. B 75, 064107 ( 10.1103/PhysRevB.75.064107) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elder KR, Rossi G, Kanerva P, Sanches F, Ying S-C, Granato E, Achim CV, Ala-Nissila T. 2012. Patterning of heteroepitaxial overlayers from nano to micron scales. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 226102 ( 10.1103/physrevlett.108.226102) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Provatas N, Elder K. 2010. Phase-field methods in materials science and engineering. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenfeld N, Athreya BP, Danzig JA. 2005. Renormalization group approach to multiscale simulation of polycrystalline materials using the phase field crystal model. Phys. Rev. E 72, 020601(R) ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.020601) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Athreya BP, Goldenfeld N, Danzig JA. 2006. Renormalization-group theory for the phase-field crystal equation. Phys. Rev. E 74, 011601 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.011601) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elder KR, Huang Zh-F, Provatas N. 2010. Amplitude expansion of the binary phase-field-crystal model. Phys. Rev. E 81, 011602 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.81.011602) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galenko PK, Sanches FI, Elder KR. 2015. Traveling wave profiles for a crystaline front invading liquid states. Phys. D 308, 1–10. ( 10.1016/j.physd.2015.06.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen SM, Cahn JW. 1979. A microscopic theory for antiphase boundary motion and its application to antiphase domain coarsening. Acta Metall. 27, 1085–1095. ( 10.1016/0001-6160(79)90196-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Saarloos W. 2003. Front propagation into unstable states. Phys. Rep. 386, 29–222. ( 10.1016/j.physrep.2003.08.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galenko P, Jou D. 2005. Diffuse-interface model for rapid phase transformations in nonequilibrium systems. Phys. Rev. E 71, 046125 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.71.046125) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galenko P, Danilov D, Lebedev V. 2009. Phase-field-crystal and Swift-Hohenberg equations with fast dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 75, 051110 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.79.051110) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galenko PK, Herlach DM. 2006. Diffusionless crystal growth in rapidly solidifying eutectic systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 150602 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.150602) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y, Humadi H, Buta D, Laird BB, Sun D, Hoyt JJ, Asta M. 2011. Atomistic simulations of nonequilibrium crystal-growth kinetics from alloy melts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 025505 ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.025505) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jou D, Galenko PK. 2013. Coarse graining for the phase-field model of fast phase transitions. Phys. Rev. E 88, 042151 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.88.042151) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malfliet W, Hereman W. 1996. The tanh method: I. Exact solutions of nonlinear evolution and wave equations. Phys. Scr. 54, 563–568. ( 10.1088/0031-8949/54/6/003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wazwaz A-M. 2004. The tanh method for travelling wave solutions of nonlinear equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 154, 713–723. ( 10.1016/S0096-3003(03)00745-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan E, Hon YC. 2002. Generalized tanh method extended to special types of nonlinear equations. Z. Naturforsch. 57, 692–700. ( 10.1515/zna-2002-0809) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wazwaz A-M. 2007. The tanh-coth method for solitons and kink solutions for nonlinear parabolic equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 188, 1467–1475. ( 10.1016/j.amc.2006.11.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kourakis I, Sultana S, Verheest F. 2012. Note on the single-shock solutions of the Korteweg-de Vries-Burgers equation. Astrophys. Space Sci. 338, 245–249. ( 10.1007/s10509-011-0958-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng Zh. 2002. The first-integral method to study the Burgers-Korteweg-de Vries equation. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 35, 343–349. ( 10.1088/0305-4470/35/2/312) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nizovtseva IG, Galenko PK, Alexandrov DV. 2016. The hyperbolic Allen-Cahn equation: exact solutions. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 49, 435201 ( 10.1088/1751-8113/49/43/435201) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu B, Zhang HQ, Xie FD. 2010. Traveling wave solutions of nonlinear partial differential equations by using the first integral method. Appl. Math. Comput. 216, 1329–1336. ( 10.1016/j.amc.2010.02.028) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Zh, Wang X. 2003. The first integral method to the two-dimensional Burgers–Korteweg-de Vries equation. Phys. Lett. A 308, 173–178. ( 10.1016/S0375-9601(03)00016-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan E. 2002. Multiple travelling wave solutions of nonlinear evolution equations using a unified algebraic method. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 35, 6853–6872. ( 10.1088/0305-4470/35/32/306) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kudryashov NA. 2009. Seven common errors in finding exact solutions of nonlinear differential equations. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulat. 14, 3507–3529. ( 10.1016/j.cnsns.2009.01.023) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim H, Sakthivel R. 2010. Travelling wave solutions for time-delayed nonlinear evolution equations. Appl. Math. Lett. 23, 527–532. ( 10.1016/j.aml.2010.01.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng X. 2000. Exploratory approach to explicit solution of nonlinear evolution equations. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 39, 207–222. ( 10.1023/A:1003615705115) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu J, Zhang H. 2001. A new method for finding exact traveling wave solutions to nonlinear partial differential equations. Phys. Lett. A 286, 175–179. ( 10.1016/S0375-9601(01)00291-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rehman T, Gambino G, Choudhury SR. 2013. Smooth and non-smooth traveling wave solutions of some generalized Camassa-Holm equations. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulat. 19, 1746–1769. ( 10.1016/j.cnsns.2013.10.029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malfliet W. 1992. Solitary wave solutions of nonlinear wave equations. Am. J. Phys. 60, 650–654. ( 10.1119/1.17120) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wazwaz A-M. 2008. The extended tanh method for new compact and noncompact solutions for the KP-BBM and the ZK-BBM equations. Chaos Solitons Fractals 38, 1505–1516. ( 10.1016/j.chaos.2007.01.135) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khater AH, Malfliet W, Callebaut DK, Kamel ES. 2002. The tanh method, a simple transformation and exact analytical solutions for nonlinear reaction-diffusion equations. Chaos Solitons Fractals 14, 513–522. ( 10.1016/S0960-0779(01)00247-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galenko PK, Abramova EV, Jou D, Danilov DA, Lebedev VG, Herlach DM. 2011. Solute trapping in rapid solidification of a binary dilute system: a phase-field study. Phys. Rev. E 84, 041143 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.84.041143) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humadi H, Hoyt JJ, Provatas N. 2016. Microscopic treatment of solute trapping and drag. Phys. Rev. E 93, 010801 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.93.010801) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kats EI, Lebedev VV, Muratov AR. 1993. Weak crystallization theory. Phys. Rep. 228, 1–91. ( 10.1016/0370-1573(93)90119-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoyt JJ, Sadigh B, Asta M, Foiles SM. 1999. Kinetic phase field parameters for the Cu-Ni system derived from atomistic computations. Acta Mater. 47, 3181–3187. ( 10.1016/S1359-6454(99)00189-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salhoumi A, Galenko PK. 2017. Analysis of interface kinetics: solutions of the Gibbs-Thomson-type equation and of the kinetic rate theory. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 192, 012014 ( 10.1088/1757-899X/192/1/012014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Provatas N, Dantzig JA, Athreya B, Chan P, Stefanovic P, Goldenfeld N, Elder KR. 2007. Using the phase-field crystal method in the multi-scale modeling of microstructure evolution. JOM 59, 83–90. ( 10.1007/s11837-007-0095-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiwa Y. 2009. Comment on ‘Renormalization-group theory for the phase-field crystal equation’. Phys. Rev. E 79, 013601 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.79.013601) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldenfeld N, Athreya BP, Dantzig JA. 2009. Reply to ‘Comment on “Renormalization-group theory for the phase-field crystal equation"’. Phys. Rev. E 79, 013602 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.79.013602) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeon D-H, Huang Zh-H, Elder KR, Thornton K. 2010. Density-amplitude formulation of the phase-field crystal model for two-phase coexistence in two and three dimensions. Philos. Mag. 90, 237–263. ( 10.1080/14786430903164572) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Zh-F. 2016. Scaling of alloy interfacial properties under compositional strain. Phys. Rev. E 93, 022803 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.93.022803) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heinonen V, Achim CV, Elder KR, Buyukdagli S, Ala-Nissila T. 2014. Phase-field-crystal models and mechanical equilibrium. Phys. Rev. E 89, 032411 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.89.032411) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang Zh-F, Elder KR, Provatas N. 2010. Phase-field-crystal dynamics for binary systems: derivation from dynamical density functional theory, amplitude equation formalism, and applications to alloy heterostructures. Phys. Rev. E 82, 021605 ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.021605) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.