Abstract

Objective

To determine the role of fatty acid oxidation on the cellular, molecular, and physiologic response of brown adipose tissue to disparate paradigms of chronic thermogenic stimulation.

Methods

Mice with an adipose-specific loss of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 2 (Cpt2A−/−), that lack mitochondrial long chain fatty acid β-oxidation, were subjected to environmental and pharmacologic interventions known to promote thermogenic programming in adipose tissue.

Results

Chronic administration of β3-adrenergic (CL-316243) or thyroid hormone (GC-1) agonists induced a loss of BAT morphology and UCP1 expression in Cpt2A−/− mice. Fatty acid oxidation was also required for the browning of white adipose tissue (WAT) and the induction of UCP1 in WAT. In contrast, chronic cold (15 °C) stimulation induced UCP1 and thermogenic programming in both control and Cpt2A−/− adipose tissue albeit to a lesser extent in Cpt2A−/− mice. However, thermoneutral housing also induced the loss of UCP1 and BAT morphology in Cpt2A−/− mice. Therefore, adipose fatty acid oxidation is required for both the acute agonist-induced activation of BAT and the maintenance of quiescent BAT. Consistent with this data, Cpt2A−/− BAT exhibited increased macrophage infiltration, inflammation and fibrosis irrespective of BAT activation. Finally, obese Cpt2A−/− mice housed at thermoneutrality exhibited a loss of interscapular BAT and were refractory to β3-adrenergic-induced energy expenditure and weight loss.

Conclusion

Mitochondrial long chain fatty acid β-oxidation is critical for the maintenance of the brown adipocyte phenotype both during times of activation and quiescence.

Keywords: Fatty acid oxidation, Brown adipose tissue, Cold induced thermogenesis, Adrenergic signaling, Adipose macrophage

Highlights

-

•

BAT requires fatty acid oxidation (FAO) for activation and quiescence.

-

•

Chronic cold and β3-adrenergic agonists elicit different effects on BAT.

-

•

Loss of FAO induces macrophage infiltration, inflammation and fibrosis in BAT.

-

•

Adipose FAO is required for acute β3-adrenergic-induced weight loss.

1. Introduction

The major function of adipose tissue is the storage of fatty acids as an energetic buffer during times of food scarcity. This is accomplished by white adipocytes that store triglyceride in large, unilocular lipid droplets throughout the body. Alternatively, brown adipocytes are tasked with maintaining body temperature by consuming fatty acids via nonshivering thermogenesis under cold environmental temperatures. Although white adipocytes contain few mitochondria, brown adipocytes are packed with mitochondria and generate heat by chemical energy fueled by increasing their cellular metabolic rate. These cells are important during the postnatal period and in times of acute cold stimulation to maintain body temperature. Cold stimulation or pharmacologic activation of adrenergic receptors on brown adipocytes dramatically increases mitochondrial respiration via the uncoupling of the mitochondrial electrochemical gradient via Uncoupling Protein 1 (UCP1). Fatty acid oxidation is critical for this process as it provides the mitochondrial bioenergetics as well as the biophysical activator of uncoupling [1], [2], [3], [4]. Fatty acids are uniquely required for UCP1-induced uncoupling. While cold induces glucose uptake into brown adipocytes and the full oxidation of glucose generates reducing equivalents, brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis and glucose uptake can be experimentally uncoupled [5], [6]. Consequently, mice with an adipose-specific deficit in fatty acid oxidation are severely cold intolerant, demonstrating an autonomous requirement for adipose fatty acid oxidation in cold-induced thermogenesis [7], [8].

Previously, we generated mice with an adipose-specific defect in fatty acid oxidation by deleting Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 2 (Cpt2), an obligate step in mitochondrial long chain fatty acid β-oxidation, specifically in adipocytes (Cpt2A−/−) [7]. These mice are severely cold intolerant as expected, but did not exhibit an obesogenic phenotype following low or high fat feeding. Similarly, Ucp1KO mice are resistant, rather than prone, to diet-induced obesity under standard housing conditions [9], [10]. Housing Ucp1KO mice at thermoneutrality (30 °C) acutely increases their adiposity, even though thermoneutrality suppresses Ucp1 in white and brown adipose tissue [11]. However, Cpt2A−/− mice did not show increased body weight gain or adiposity at thermoneutrality even though interscapular BAT was lost following housing at 30 °C [12]. This suggests adipose bioenergetics alone is not required for the homeostatic regulation of body weight.

The expression of genes required for thermogenesis are increased with cold and adrenergic stimulation and suppressed through thermoneutral housing. This thermogenic programing and plasticity is an important component of long-term cold tolerance. Although fatty acid oxidation is required for thermogenesis, we were surprised that Cpt2A−/− mice could not induce the expression of thermogenic genes such as Ucp1. Acute cold exposure (21 °C–4 °C) or the β3-adrenergic agonist, CL-316243, failed to induce Ucp1, Pgc1α, and Dio2 among others in Cpt2A−/− BAT [7]. This deficiency in transcriptional programing was further exacerbated by acclimatizing mice at 30 °C [12]. Therefore, Cpt2A−/− mice represent a unique model to dissect the physiological functions of brown adipocytes in vivo because they exhibit molecular, cellular, and biochemical defects that prevented canonical BAT or beige cell function.

To understand the role of fatty acid oxidation to adipose tissue structure, function, and physiology, we subjected Cpt2A−/− mice to disparate thermogenic stimuli including a β3-adrenergic agonist (CL-316243), a thyroid hormone agonist (GC-1) and altered ambient temperature. Here we show that pharmacologic thermogenic agonists induced a loss of UCP1 and BAT morphology in Cpt2A−/− mice, and failed to induce UCP1 and thermogenic programing in white adipose tissue (WAT). However, chronic cold stimulation induced UCP1 and thermogenic programming albeit to a lesser extent in Cpt2A−/− adipose. Structural analysis of Cpt2A−/− BAT revealed increased macrophage infiltration, inflammation, and fibrosis. Finally, obese Cpt2A−/− mice housed at thermoneutrality exhibited a loss in interscapular BAT and were refractory to β-adrenergic-induced energy expenditure and weight loss. These data show that fatty acid oxidation is critical for the maintenance of the brown adipocyte phenotype, particularly under conditions of metabolic stress.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Animals and diets

Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox littermate control mice were generated as previously described [7], [12]. For temperature acclimation studies, 12-week old male and female Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice were housed in an animal incubator (Key Scientific) at the indicated temperatures for 10 days on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle and fed a standard chow diet (Teklad Global Rodent Diets). For studies using GC-1 (Tocris; 4554) and CL-316243 (Tocris; 1499), 12-week old male and female Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice were housed in a facility with ventilated racks on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle with access to a standard chow diet (Teklad Global Rodent Diets) and were subjected to an intraperitoneal injection with vehicle (0.9% NaCl), CL-316243 (1 mg/kg), or GC-1 (0.3 mg/kg) for 10 consecutive days. Tissue depots for both respective studies were collected on day 11, and were either snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, or stored in Formalin (Sigma) for H&E staining (AML Laboratories).

For the diet study, male Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice were housed at room temperature on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle and fed a 60% high-fat diet (Research Diets; D12492) starting at 6-weeks of age (12 weeks on diet). At 12-weeks of age, mice were transferred to an animal incubator at 30 °C on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. At 17-weeks of age, the same mice were subjected to an intraperitoneal injection with CL-316243 (1 mg/kg) for 10 consecutive days. Body weights were measured on a weekly basis and on a daily basis during injections with CL-316243. At approximately 18-weeks of age, following the last injection with CL-316243 on day 10, the same mice were individually housed in Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System (Columbus Instruments) cages on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. O2 and CO2 consumption and production, respectively, food, and water intake, and home–cage activity were measured continuously. Data were collected for 96 h for ad libitum and a 24 h fasting period. At the end of the study, the same mice were injected with CL-316243 (10 mg/kg) and were monitored for 3 h. Body fat and lean mass of the same mice was measured via magnetic resonance imaging analysis (Minispec MQ10). BAT, iWAT, and gWAT depots were collected for H&E staining.

For the CL-316243 time course experiments, 12-week old male and female Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice were housed at room temperature on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle with access to a standard chow diet (Teklad Global Rodent Diets) and subjected to an intraperitoneal injection with CL-316243 (1 mg/kg) at the indicated time points. BAT depots were collected 24 h following the last injection with CL-316243 (days 3, 5, 7, 9, or 11). All procedures were performed in accordance with the NIH's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and under the approval of the Johns Hopkins Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Analysis of gene expression by quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol followed by the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). RNA was reverse transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosciences). 1–2 ug of cDNA was diluted to 2 ng/ml and was amplified by specific primers in a 20 μl reaction using SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Analysis of gene expression was carried out in a CFX Connect Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). For each gene, mRNA expression was calculated as 2ˆdeltaCT relative to Rpl22 and 18s expression [13]. Primers and gene information are provided in Table S1.

2.3. Western blot

BAT, iWAT, and gWAT depots were homogenized with 300–500 ul of RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% deoxycholate) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and phospho-STOP cocktail (Roche), followed by pelleting of the insoluble debris at 13,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. The protein concentrations of lysates were determined by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific), and 30 μg of lysate was separated by Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Protran BA 83, Whatman), blocked in 3% BSA in 1X TBST (Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20), and incubated with primary antibodies overnight. The blots were probed with the following antibodies: Ucp1 (Sigma; U6382), Ndufb8, Sdhb, Uqcrc2, Atp5a (MitoProfile total OXPHOS, Abcam; ab110413), Aco2 (Cell Signaling; 6922), Mcad (GeneTex; GTX32421), Pcx (Abcam; ab128952), Vdac (Calbiochem; PC548), Pdh E2/E3bp (Abcam; ab110333), Acot2 (Sigma; SAB2100030), beta-Actin (Sigma; A2228), and Hsc-70 (Santa Cruz; sc-7298). Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse (Invitrogen), or HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (GE Healthcare) or anti-rabbit (GE Healthcare) secondary antibodies were used appropriately. Images were collected and analyzed using an Alpha Innotech FluorChemQ.

2.4. Transmission electron microscopy

Samples for TEM were collected and processed as described with minor modifications [14]. BAT was collected and immersed in 3% glutaraldehyde PBS solution and cut into ∼0.5 mM sections with a Mcilwain tissue chopper. The tissue was then fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde, 1% tannic acid, 0.1 M cacodylic acid, 3 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.2, 615 mOsmol). They were then washed with 0.1 M cacodylic acid, 3.5% sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.2, 331 mOsmol). Then they were postfixed in 0.1 M cacodylic acid, 3 mM MgCl2, 2% OsO4 solution for 2 h. The tissue was then processed for embedding, sectioned and imaged on a Hitachi 7600 transmission electron microscope as we have previously reported [15].

2.5. Statistical analyses

Pairwise comparisons were calculated using a two-tailed Student's t-test. Two-way ANOVA was utilized for repeated measures such as weight gain over time. Significance was determined as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. β3-adrenergic and thyroid agonists suppress BAT UCP-1 and the browning of iWAT in Cpt2A−/− mice

Previously, we generated mice with a loss of long chain fatty acid β-oxidation in adipose tissue by crossing Cpt2 floxed mice with AdipoQ-Cre transgenic mice (herein Cpt2A−/−). Fatty acid β-oxidation in adipose tissue was not only critical for thermogenesis as expected but also for the expression of thermogenic genes by acute cold or β3-adrenergic stimulation [7], [12]. Furthermore, acclimatization at thermoneutrality greatly exacerbated this defect whereby acute β3-adrenergic stimulation failed to elicit the stimulation of Ucp1 expression in Cpt2A−/− BAT [12]. Here, we examined the effect of a chronic low dose of two independent pharmacologic browning agents on BAT, iWAT and gWAT. This was accomplished by administering 10 days of vehicle, a β3-adrenergic agonist CL-316243 (1 mg/kg/day), or a thyroid hormone agonist GC-1 (0.3 mg/kg) to both Cpt2A−/− mice and Cpt2lox/lox littermate controls [16], [17]. Tissue was then collected 24 h following the final injection for examination of histologic, molecular and biochemical thermogenic indicators.

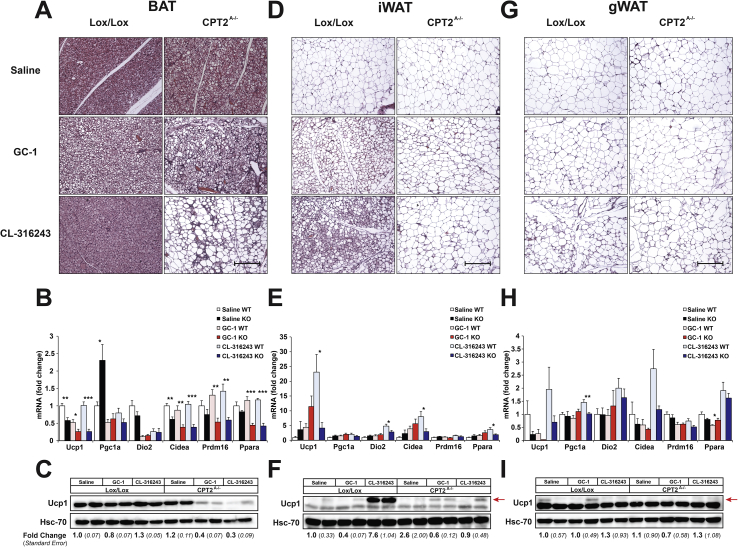

Under all conditions, the BAT of Cpt2A−/− mice contained larger lipid droplets as we have previously observed. Following GC-1 treatment, the increase in lipid droplet size was further exacerbated. Following CL-316243 treatment, the BAT was largely eliminated with mainly large unilocular adipocytes remaining (Figure 1A). Next, we examined the transcriptional response to chronic stimulation. Ucp1 and Cidea mRNA was suppressed in Cpt2A−/− BAT (Figure 1B). Pgc1α was increased under vehicle conditions but this difference was eliminated by both agonists. Prdm16 and Pparα mRNA was suppressed in CL-316243 and GC-1 treated Cpt2A−/− mice (Figure 1B). Finally, UCP1 protein was assessed by western blot. Surprisingly, both CL-316243 and GC-1 greatly suppressed UCP1 (∼3fold) in in Cpt2A−/− BAT (Figure 1C). These data show that two independent pharmacologic browning agents result in not only refractory thermogenic programing in BAT but the suppression of BAT morphology and loss of UCP1 expression.

Figure 1.

Effect of CL-316243 and GC-1 on adipose tissue of Cpt2A−/−mice. A) H&E staining of BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days. Scale bar, 200 um. B) mRNA expression in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days (n = 6). C) UCP1 protein expression in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days. D) H&E staining of iWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days. Scale bar, 200 um. E) mRNA expression in iWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days (n = 6). F) UCP1 protein expression in iWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days. Arrow indicates Ucp1 band. G) H&E staining of gWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days. Scale bar, 200 μm H) mRNA expression in gWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days (n = 6). I) UCP1 protein expression in gWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days. Arrow indicates Ucp1 band. Western blot quantification is expressed as fold change +/− SE (n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The loss of interscacuplar BAT generally leads to an increase in the browning of WAT. To assess the browning of WAT, iWAT and gWAT were examined. Both CL-316243 and GC-1 generated significant browning of iWAT in control mice based on histology, mRNA and UCP1 protein (>7 fold) expression. However, CL-316243 and GC-1 had little effect on the browning of Cpt2A−/− iWAT (Figure 1D–F). There was little to no effect of CL-316243 or GC-1 on the browning of gWAT in either control or Cpt2A−/− mice (Figure 1G–I). These data show that pharmacologic browning agents induce the loss of classical BAT and also fail to induce the browning in WAT in Cpt2A−/− mice.

3.2. β3-adrenergic and thyroid agonists generate a mitochondrial protein imbalance in Cpt2A−/− BAT

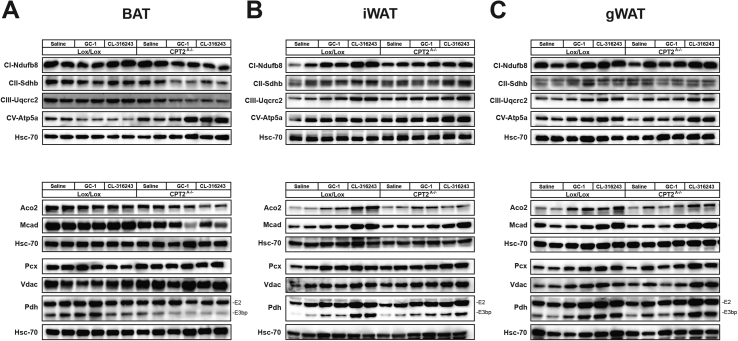

The loss of fatty acid oxidation in adipose tissue resulted in the agonist-induced loss of UCP1. To understand the effect of a loss of fatty acid oxidation on mitochondrial proteins in general, we performed western blots for other mitochondrial proteins in BAT, iWAT and gWAT in control and Cpt2A−/− mice. Similar to UCP1, NDUFB8, SDHB UQCRC2, ACO2, and MCAD where suppressed (∼2fold) in the BAT of CL-316243 and GC-1 treated Cpt2A−/− mice (Figure 2A). Some mitochondrial proteins showed no difference in abundance such as PCX and VDAC (Figure 2A). These data suggest that browning agonists result in a loss of many but not all mitochondrial proteins in Cpt2A−/− BAT.

Figure 2.

Effect of CL-316243 and GC-1 on mitochondrial proteins in adipose tissue of Cpt2A−/−mice. A) Western blots of mitochondrial proteins in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days. B) Western blots of mitochondrial proteins in iWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days. C) Western blots of mitochondrial proteins in gWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days.

Next, we examined the effect of CL-316243 and GC-1 on iWAT and gWAT mitochondrial proteins. Both browning agonists increased mitochondrial protein abundance in iWAT of control mice. In contrast to UCP1, CL-316243 and GC-1 also induced mitochondrial protein abundance in iWAT of Cpt2A−/− mice but to a lesser extent (Figure 2B). Although CL-316243 and GC-1 did not increase UCP1 in gWAT, they did increase mitochondrial protein abundance in gWAT. Again, Cpt2A−/− mice also increased mitochondrial protein abundance in gWAT but to a lesser extent (Figure 2C). These data show that although Cpt2A−/− WAT does not increase UCP1 in response to browning agonists, they do increase mitochondrial protein abundance suggesting an alternative thermogenic program.

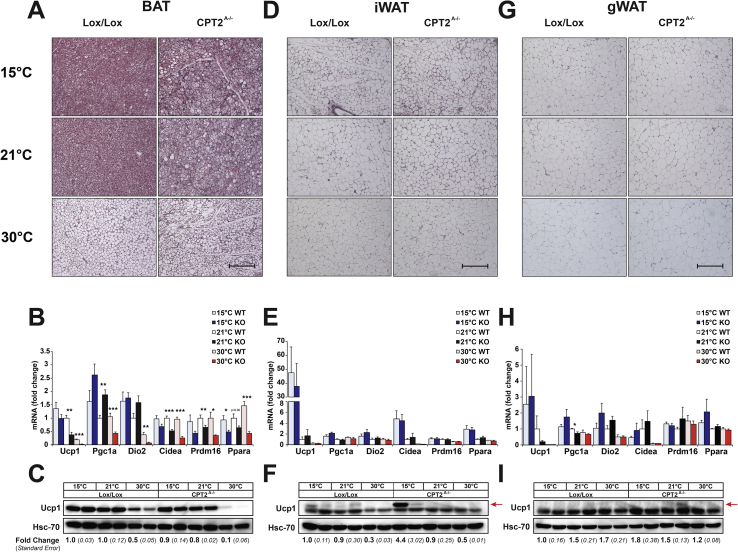

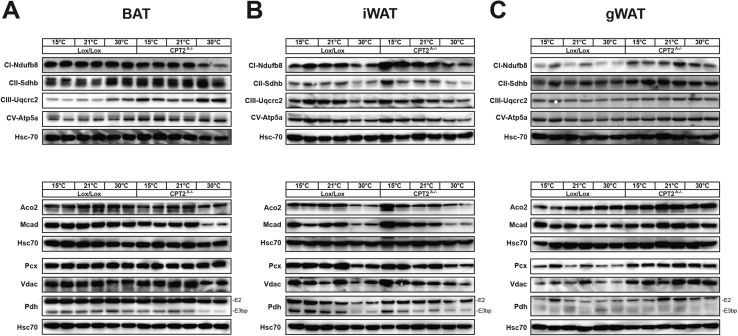

3.3. Chronic cold stimulation induces UCP1 in BAT and iWAT in Cpt2A−/− mice

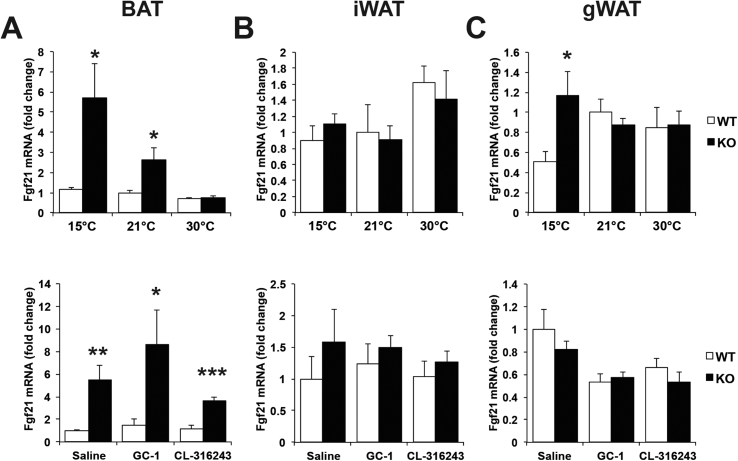

CL-316243 and GC-1 are pharmacologic agents aimed to simulate cold stimulation. To understand how a physiologic cold stimulation affects adipose tissue in the absence of fatty acid oxidation, control and Cpt2A−/− mice were housed at 15 °C, 21 °C and 30 °C for 10 days to match the pharmacologic intervention. Although Cpt2A−/− BAT contains more lipid droplet area and less Ucp1 mRNA and UCP1 protein under all temperatures, chronic cold still induces Ucp1 mRNA and UCP1 protein (Figure 3 A–C). Consistent with our previous results, housing Cpt2A−/− mice at thermoneutrality eliminates UCP1 and classical interscapular BAT morphology [12]. Also, in contrast to thermogenic agonists, chronic cold elicited the browning of iWAT at the histological, mRNA and protein level in Cpt2A−/− mice (Figure 3D–F). Again, gWAT showed little evidence of browning and there was no difference between control and Cpt2A−/− mice (Figure 3G–I). Housing mice at thermoneutrality had little effect on the overall protein abundances of mitochondrial proteins. However, thermoneutrality suppressed mitochondrial protein abundance in Cpt2A−/− BAT, suggesting that thermoneutrality requires fatty acid oxidation to maintain BAT integrity (Figure 4A). iWAT responded to cold challenge by increasing mitochondrial proteins equally in control and Cpt2A−/− mice (Figure 4B). gWAT elicited minor effects on mitochondrial protein abundance in both genotypes (Figure 4C). Finally, we examined the mRNA expression of Fgf21 in adipose tissue of both cold and agonist-induced control and Cpt2A−/− mice. Fgf21 is highly induced in liver and muscle that are deficient in fatty acid oxidation [18], [19], [20]. Cold exposure increased the expression of Fgf21 in Cpt2A−/− BAT (Figure 5A). Adrenergic or thyroid agonists did not further potentiate this response (Figure 5A). iWAT and gWAT did not show significant changes in Fgf21 expression (Figure 5B,C). Together, these results show that cold exposure uniquely regulates adipose function compared to β3-adrenergic and thyroid agonist stimulation.

Figure 3.

Effect of ambient temperature on adipose tissue of Cpt2A−/−mice. A) H&E staining of BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days. Scale bar, 200 um. B) mRNA expression in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days (n = 6). C) UCP1 protein expression in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days. D) H&E staining of iWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days. Scale bar, 200 um. E) mRNA expression in iWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days (n = 6). F) UCP1 protein expression in iWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days. Arrow indicates Ucp1 band. G) H&E staining of gWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days. Scale bar, 200 um. H) mRNA expression in gWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days (n = 6). I) UCP1 protein expression in gWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days. Arrow indicates Ucp1 band. Western blot quantification is expressed as fold change +/− SE (n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Effect of ambient temperature on mitochondrial proteins in adipose tissue of Cpt2A−/−mice. A) Western blots of mitochondrial proteins in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days. B) Western blots of mitochondrial proteins in iWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days. C) Western blots of mitochondrial proteins in gWAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days.

Figure 5.

Loss of fatty acid oxidation induces Fgf21 in BAT. A) Fgf21 expression in BAT of 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to different ambient temperature or thermogenic agonists for 10 days (n = 6). B) Fgf21 expression in iWAT of 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to different ambient temperature or thermogenic agonists for 10 days (n = 6). C) Fgf21 expression in gWAT of 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to different ambient temperature or thermogenic agonists for 10 days (n = 6). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

3.4. Brown adipose tissue of Cpt2A−/− mice exhibit macrophage infiltration, inflammation and fibrosis

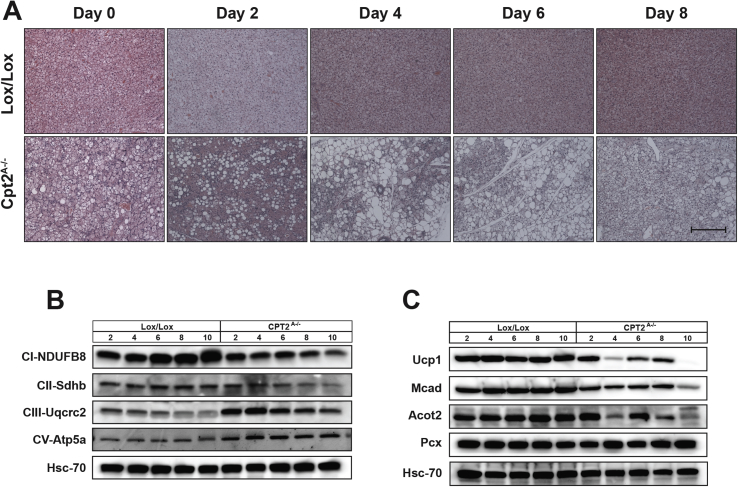

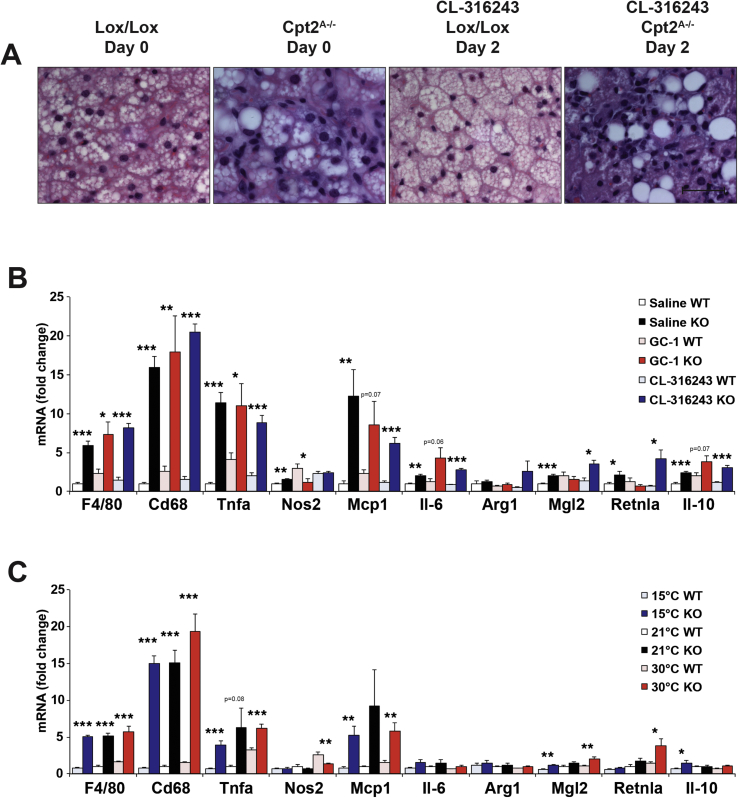

To understand the development of BAT dysfunction in response to browning agonists, control and Cpt2A−/− mice were again treated with CL-316243 (1 mg/kg/day) and BAT was collected over 10 days. Gross and histological examination revealed that after 4 days of CL-316243 treatment, most of the interscapular BAT had become dysmorphic (Figure 6A). Additionally, UCP1 protein and other mitochondrial proteins were suppressed by day 4 (Figure 6B,C). Upon closer examination, Cpt2A−/− BAT contained an abundance of infiltrating leukocytes (Figure 7A). Therefore, we examined BAT for markers of macrophage infiltration and local inflammation. Cpt2A−/− BAT exhibited increased markers for macrophage mRNA such as F4/80 and Cd68 irrespective of CL-316243, GC-1 or temperature (Figure 7B,C). Additionally, Cpt2A−/− BAT expressed higher Tnfα, and Mcp1 as well as other inflammatory markers consistent with higher inflammatory status in the Cpt2A−/− BAT depot (Figure 7B,C). These data show that Cpt2A−/− BAT (but not WAT [7]) exhibits significant chronic inflammation.

Figure 6.

Time course of CL-316243 mediated dysfunction in Cpt2A−/−BAT. A) H&E staining of BAT from Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice after injection with 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8 days. Scale bar, 200 um. B) Western blots of representative proteins in oxidative phosphorylation complexes I, II, III, and V in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days. C) Mitochondrial protein expression in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days.

Figure 7.

Loss of adipose fatty acid oxidation causes macrophage infiltration and inflammation in BAT. A) H&E staining of BAT from Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice after injection with 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8 days. B) mRNA expression of macrophage & inflammatory genes in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days (n = 6). C) mRNA expression of macrophage & inflammatory genes in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days (n = 6). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

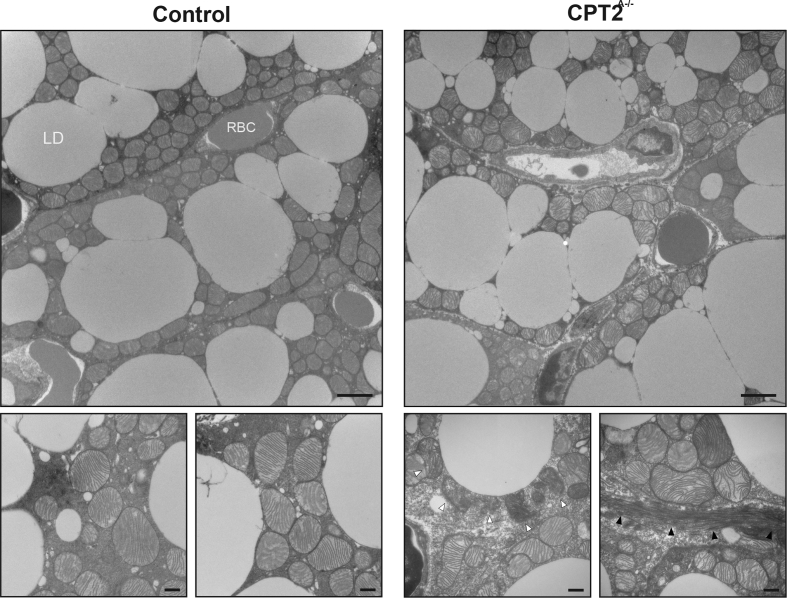

To examine the subcellular structure of BAT, control and Cpt2A−/− BAT was examined by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). Consistent with the histological and transcriptional data showing increased macrophage infiltration, Cpt2A−/− BAT exhibited an abundance of phagocytic cells. Based on the substantial changes in mitochondrial protein abundance, we were surprised that many mitochondria of Cpt2A−/− BAT exhibited normal morphology with abundant cristae. However, Cpt2A−/− BAT did exhibit evidence of dysmorphic mitochondria (Figure 8 white arrowheads) and significant cellular and subcellular heterogeneity. Strikingly, Cpt2A−/− BAT exhibited abundant fibrin deposition (Figure 8 black arrowheads). These data show that Cpt2A−/− mice exhibit structurally normal BAT and mitochondria, interspersed with dysmorphic cells and organelles including large fibrotic areas.

Figure 8.

Transmission Electron Micrographs of control and Cpt2A−/−BAT. TEM of BAT from 16-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice. Scale bars, 2 um and 500 nm, respectively. White arrowheads pointing to dysmorphic mitochondria. Black arrowheads pointing to fibrin deposition. Lipid Droplet (LD), Red Blood Cell (RBC).

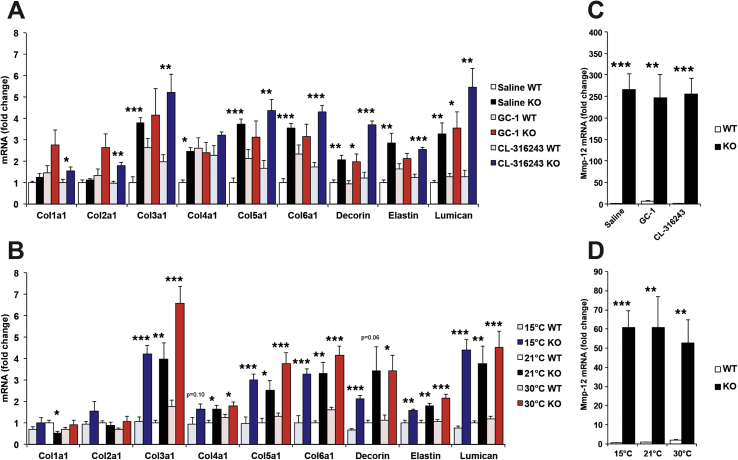

To further examine the fibrin deposition, we assayed genes involved in adipose tissue fibrosis [21]. First, we examined microarray data that we have previously published [12]. This data revealed a large number of genes upregulated in Cpt2A−/− BAT. To validate these results, we performed qPCR analysis of genes identified by microarray analysis. Cpt2A−/− BAT showed significant upregulation of collagen genes including consistent changes in Col3a1, Col5a1 and Col6a1 (Figure 9A,B). Additionally, Decorin, Elastin, and Lumican were significantly upregulated under all conditions (Figure 9A,B). Finally, we identified Mmp12, a macrophage specific enzyme that degrades ECM, massively upregulated under all conditions in Cpt2A−/− BAT (Figure 9C,D). Together these data suggest that the loss of adipose fatty acid oxidation results in increased tissue turnover and inflammation in BAT, and that fatty acid oxidation is important for BAT cellular and tissue maintenance.

Figure 9.

Loss of adipose fatty acid oxidation induces genes in extracellular matrix. A) mRNA expression of collagen and extracellular matrix genes in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days (n = 6). B) mRNA expression of collagen and extracellular matrix genes in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days (n = 6). C) Mmp-12 mRNA expression in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice injected with Saline, 0.3 mg/kg GC-1, or 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days (n = 6). D) Mmp-12 mRNA expression in BAT from 12-week old Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox mice acclimated to 15 °C, 21 °C, or 30 °C for 10 days (n = 6). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

3.5. Adipose fatty acid oxidation is required for acute β3-adrenergic-induced weight loss

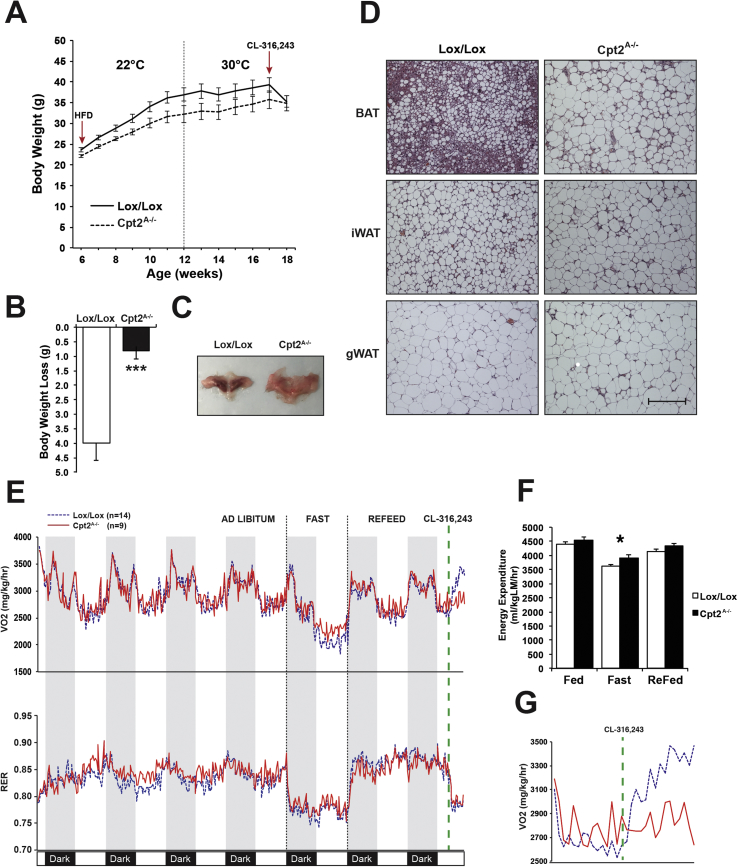

Previously we showed that Cpt2A−/− mice were not more prone to weight gain on high or low fat diets, and in contrast to Ucp1KO mice, were not prone to weight gain at thermoneutrality even though the adipose tissue was bioenergetically and transcriptionally incompetent for thermogenesis [7], [12]. Additionally, both housing at thermoneutrality and 10 days of CL-316243 eliminate BAT in Cpt2A−/− mice. Here we used Cpt2A−/− mice to understand the physiologic role of BAT on body weight gain. First, control and Cpt2A−/− mice were placed on a high fat diet for 6 weeks to induce an obese phenotype. Then they were placed at thermoneutrality and remained on the HFD for an additional 5 weeks to eliminate BAT from Cpt2A−/− mice. Under this paradigm, there was, again, no genotypic difference in body weight of the mice (Figure 10A). The mice were then given 10 days of CL-316243 (1 mg/kg/day). CL-316243 induced rapid weight loss in control mice, but Cpt2A−/− mice were resistant to CL-316243 induced weight loss (Figure 10B). As expected, upon gross examination, Cpt2A−/− mice did not exhibit an appreciable interscapular BAT depot (Figure 10C). Histological examination confirmed a significant loss of BAT without concomitant browning of iWAT or gWAT in Cpt2A−/− mice (Figure 10D). Examination of energy expenditure and RER by indirect calorimetry did not reveal differences during ad libitum feeding (Figure 10E). However, Cpt2A−/− mice better maintained energy expenditure during a 24hr fast (Figure 10F). Administration of CL-316243 revealed a robust increase in energy expenditure in control mice, but Cpt2A−/− mice were refractory to CL-316243 administration as expected (Figure 10G). Interestingly, control and Cpt2A−/− mice both exhibited decreased RER upon CL-316243, suggesting that although CL-316243 induced lipolysis equally well in both animals, acute changes in energy expenditure require adipose fatty acid oxidation.

Figure 10.

Adipose fatty acid oxidation is required for acute β3-adrenergic-induced weight loss. A) Body weights male Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox littermate control mice on HFD for 6-weeks at 22 °C and 6 weeks at 30 °C. Arrows indicate the start of high-fat diet feeding and injections with 1 mg/kg CL-316243 (n = 10–14). B) Loss in body weight of male Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox littermate control mice after injections with 1 mg/kg CL-316243 for 10 days at 30 °C (n = 10–14). C) Gross interscapular BAT morphology of male Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox littermate control mice housed at 30 °C on high-fat diet plus 1 mg/kg CL-316243 injections for 10 days. D) H&E staining of BAT, iWAT, and gWAT from male Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox littermate control mice housed at 30 °C on high-fat diet plus 1 mg/kg CL-316243 injections for 10 days. Scale bar, 200 um. E) VO2 consumption and RER of male Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox littermate control mice housed at 30 °C on high-fat diet plus 1 mg/kg CL-316243 injections for 10 days (n = 9–14). Data were collected during a 96 h ad libitum period, 24 h fast, 24 h reefed, and 3 h after injection with 10 mg/kg CL-316243. F) Energy expenditure of male Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox littermate control mice housed at 30 °C on high-fat diet plus 1 mg/kg CL-316243 injections for 10 days under fed, fast, and re-fed conditions (n = 9–14). G) VO2 consumption of male Cpt2A−/− and Cpt2lox/lox littermate control mice housed at 30 °C on high-fat diet plus 1 mg/kg CL-316243 injections for 10 days. VO2 consumption was measured for 3 h after injection with 10 mg/kg CL-316243 (n = 9–14). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

There has been great interest in the development of new therapies to combat human obesity. Many have suggested that recruiting and harnessing brown adipose tissue to dissipate as opposed to store fatty acids would represent a viable anti-obesity therapy [22], [23]. Indeed, the activation of thermogenesis by the administration of adrenergic ligands or thyroid agonists has been shown to reduce adiposity in rodents [16], [17]. Chemical uncoupling agents are effective weight loss agents in humans although dangerous as originally administered [24], [25]. Second generation tissue specific uncouplers may circumvent this toxicity [26], [27]. However, from a mechanistic standpoint, it is not clear what the adipose-specific roles of increasing energy expenditure are in combating obesity. That is, are the actions of these weight loss agents due to an increase in adipose bioenergetics or by acting on multiple tissues simultaneously. Even in cases where brown adipose tissue has been specifically targeted and shown to prevent weight gain, it is not clear what the role autonomous bioenergetics plays as opposed to endocrine roles for adipocytes [28]. In order to understand the bioenergetic roles of adipocytes in vivo we have inhibited the ability of adipose tissue to oxidize fatty acids, and consequently limited their ability to increase energy expenditure in response to cold or thermogenic agonists.

We have previously shown that acute cold failed to induce Ucp1 in BAT of Cpt2A−/− mice [7]. Additionally, the β3-adrenergic agonist CL-316243, adrenergic agonist isopreterenol and adenylate cyclase activator forskolin all failed to induce Ucp1 in Cpt2A−/− BAT even though PKA signaling and CREB activation remained intact [7]. To understand the long-term effects of thermogenic activation in mice with defective BAT, we treated control and Cpt2A−/− mice with a low dose of CL-316243 and the thyroid hormone agonist GC-1 for 10 days. Under these conditions, both agonists induced not just a failure to induce Ucp1 in BAT, but UCP1 was lost in addition to BAT morphology. Therefore, activation of these thermogenic pathways was not merely refractory in Cpt2A−/− mice but was detrimental. The inability to oxidize fatty acids resulted in agonist-induced deformation of BAT. Normally when classical interscapular BAT is lost, there is a concomitant increase in beige adipocytes. Surprisingly, this did not occur in Cpt2A−/− mice as these mice were also refractory to the browning of white adipose tissue. These data demonstrate the requirement of adipose fatty acid oxidation to BAT function and survival following chronic activation by disparate thermogenic agonists.

An examination of Cpt2A−/− BAT histology revealed a significant infiltration of leukocytes. Transcriptional profiling showed that Cpt2A−/− BAT exhibited a significant macrophage infiltration with corresponding inflammatory markers. Macrophage infiltration has been shown to suppress Ucp1 [29]. Therefore, it is conceivable that the excessive macrophage infiltration into BAT could be partially responsible for the suppression in UCP1 expression in Cpt2A−/− mice although the role of macrophages in cold-induced thermogenesis remains unclear [30]. These results along with the imbalance in mitochondrial protein abundance prompted us to take a closer look at BAT from Cpt2A−/− mice. Therefore, we examined the cellular and intracellular morphology of Cpt2A−/− BAT by TEM. Although, the BAT depot is much smaller in Cpt2A−/− mice, many of the brown adipocytes that remained exhibited surprisingly normal ultrastructure. However, there was more heterogeneity in Cpt2A−/− BAT, which exhibited unhealthy adipocytes and dysmorphic mitochondria. Strikingly, Cpt2A−/− BAT exhibited large patches of intercellular fibrin depositions as well as infiltrating phagocytic cells. These static snapshots likely portend a highly dynamic BAT in Cpt2A−/− mice owning to the importance of fatty acid oxidation for the survival and maintenance of brown adipocytes.

We were surprised to see that chronic cold exposure (15 °C) did not result in a loss of BAT but rather increased Ucp1 in Cpt2A−/− mice. BAT from Cpt2A−/− mice always expresses a lower amount of Ucp1 but Ucp1 is nonetheless regulated by ambient temperature in Cpt2A−/− mice. This is in contrast to the acute (4 °C) cold exposure of Cpt2A−/− mice [7]. Ucp1KO mice are acutely sensitive to 4 °C, but can survive cold exposure if they are first acclimatized to 15 °C [31]. Chronic cold acclimatization likely elicits a unique program from acute cold stimulation (shock) that does not rely on adipose fatty acid oxidation [32]. It may well be simply the difference in kinetics, or the signals elicited by cold acclimatization may be different than cold stimulation. In contrast, Cpt2A−/− mice acclimatized to thermoneutrality (30 °C), lose BAT similar to acute cold stimulation. Therefore, fatty acid oxidation is required both for survival of brown adipocytes under acute stimulated and quiescent states. Interestingly, although chronic cold stimulation somewhat rescues BAT structure in Cpt2A−/− mice, there was not a resolution in macrophage infiltration. Again, we would speculate that BAT turnover is high under all conditions, but recruitment of new brown adipocytes outpaces adipocyte demise during chronic cold stimulation.

Finally, we examined the physiologic significance of adipose fatty acid oxidation and brown/beige cells in general. We essentially eliminated brown adipocytes in Cpt2A−/− mice by maintaining them at thermoneutrality followed by 10 days of CL-316243 administration. This evoked the loss of interscapular BAT while inhibiting the browning of white adipose tissue. While there was again no difference in body weight between control and Cpt2A−/− mice, obese Cpt2A−/− mice were resistant to energy expenditure and weight loss elicited by CL-316243. Therefore, brown adipose tissue is an important component to acute adrenergic-induced weight loss, but long-term physiologic adaptations likely prevent changes in weight over the long-term. Still, it is not clear if this will be an effective weight loss strategy in adult obese humans that have a limited quantity of brown adipose tissue.

Fatty acid oxidation is an important metabolic process in adipose tissue, particularly for brown and beige adipocytes. The loss of adipose fatty acid oxidation results in severe cold intolerance but normal adiposity. We have found that fatty acid oxidation contributes not only to adipose bioenergetics but is also critical for brown adipose tissue survival under acute thermogenic activation and during times of BAT quiescence. These data show that fatty acid oxidation is critical for the maintenance of the brown adipocyte phenotype, particularly under conditions of metabolic stress.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health grant R01NS072241 and American Diabetes Association grant #1-16-IBS-313 to M. J. W. E. G. H. was supported by the Johns Hopkins PREP grant R25GM109441.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2017.11.004.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Author contributions

E. G. H., J. L., and J. C. conducted the experiments and analyzed the results. M. J. W. conceived the idea for the project. M. J. Wc. wrote the paper with input and approval of all authors.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Guerra C., Koza R.A., Walsh K., Kurtz D.M., Wood P.A., Kozak L.P. Abnormal nonshivering thermogenesis in mice with inherited defects of fatty acid oxidation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;102(9):1724–1731. doi: 10.1172/JCI4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolwani R.J. Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in gene-targeted mice. PLoS Genetics. 2005;1(2):e23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuler A.M., Gower B.A., Matern D., Rinaldo P., Vockley J., Wood P.A. Synergistic heterozygosity in mice with inherited enzyme deficiencies of mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2005;85(1):7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fedorenko A., Lishko P.V., Kirichok Y. Mechanism of fatty-acid-dependent UCP1 uncoupling in brown fat mitochondria. Cell. 2012;151(2):400–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hankir M.K. Dissociation between brown adipose tissue 18F-FDG uptake and thermogenesis in uncoupling protein 1-deficient mice. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2017;58(7):1100–1103. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.186460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen J.M. beta3-Adrenergically induced glucose uptake in brown adipose tissue is independent of UCP1 presence or activity: mediation through the mTOR pathway. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2017;6(6):611–619. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J., Ellis J.M., Wolfgang M.J. Adipose fatty acid oxidation is required for thermogenesis and potentiates oxidative stress-induced inflammation. Cell Reports. 2015;10(2):266–279. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis J.M. Adipose acyl-CoA synthetase-1 directs fatty acids toward beta-oxidation and is required for cold thermogenesis. Cell Metabolism. 2010;12(1):53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enerback S. Mice lacking mitochondrial uncoupling protein are cold-sensitive but not obese. Nature. 1997;387(6628):90–94. doi: 10.1038/387090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X., Rossmeisl M., McClaine J., Riachi M., Harper M.E., Kozak L.P. Paradoxical resistance to diet-induced obesity in UCP1-deficient mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111(3):399–407. doi: 10.1172/JCI15737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldmann H.M., Golozoubova V., Cannon B., Nedergaard J. UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metabolism. 2009;9(2):203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee J., Choi J., Aja S., Scafidi S., Wolfgang M.J. Loss of adipose fatty acid oxidation does not potentiate obesity at thermoneutrality. Cell Reports. 2016;14(6):1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzalez-Hurtado E. Loss of macrophage fatty acid oxidation does not potentiate systemic metabolic dysfunction. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2017;312(5):E381–E393. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00408.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanchette-Mackie E.J., Scow R.O. Movement of lipolytic products to mitochondria in brown adipose tissue of young rats: an electron microscope study. The Journal of Lipid Research. 1983;24(3):229–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowman C.E., Zhao L., Hartung T., Wolfgang M.J. Requirement for the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier in mammalian development revealed by a hypomorphic allelic series. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2016;36(15):2089–2104. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00166-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin J.Z. Pharmacological activation of thyroid hormone receptors elicits a functional conversion of white to brown fat. Cell Reports. 2015;13(8):1528–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Himms-Hagen J. Effect of CL-316,243, a thermogenic beta 3-agonist, on energy balance and brown and white adipose tissues in rats. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266(4 Pt 2):R1371–R1382. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.4.R1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J., Choi J., Scafidi S., Wolfgang M.J. Hepatic fatty acid oxidation restrains systemic catabolism during starvation. Cell Reports. 2016;16(1):201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J. Loss of hepatic mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid oxidation confers resistance to diet-induced obesity and glucose intolerance. Cell Reports. 2017;20(3):655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandanmagsar B. Impaired mitochondrial fat oxidation induces FGF21 in muscle. Cell Reports. 2016;15(8):1686–1699. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan T. Metabolic dysregulation and adipose tissue fibrosis: role of collagen VI. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2009;29(6):1575–1591. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01300-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vernochet C., McDonald M.E., Farmer S.R. Brown adipose tissue: a promising target to combat obesity. Drug News & Perspectives. 2010;23(7):409–417. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2010.23.7.1487083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harms M., Seale P. Brown and beige fat: development, function and therapeutic potential. Nature Medicine. 2013;19(10):1252–1263. doi: 10.1038/nm.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldgof M., Xiao C., Chanturiya T., Jou W., Gavrilova O., Reitman M.L. The chemical uncoupler 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) protects against diet-induced obesity and improves energy homeostasis in mice at thermoneutrality. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289(28):19341–19350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.568204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundlingh J., Dargan P.I., El-Zanfaly M., Wood D.M. 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP): a weight loss agent with significant acute toxicity and risk of death. Journal of Medical Toxicology : Official Journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 2011;7(3):205–212. doi: 10.1007/s13181-011-0162-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perry R.J. Reversal of hypertriglyceridemia, fatty liver disease, and insulin resistance by a liver-targeted mitochondrial uncoupler. Cell Metabolism. 2013;18(5):740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perry R.J., Zhang D., Zhang X.M., Boyer J.L., Shulman G.I. Controlled-release mitochondrial protonophore reverses diabetes and steatohepatitis in rats. Science. 2015;347(6227):1253–1256. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang G.X., Zhao X.Y., Lin J.D. The brown fat secretome: metabolic functions beyond thermogenesis. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;26(5):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakamoto T. Macrophage infiltration into obese adipose tissues suppresses the induction of UCP1 level in mice. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2016;310(8):E676–E687. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00028.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer K. Alternatively activated macrophages do not synthesize catecholamines or contribute to adipose tissue adaptive thermogenesis. Nature Medicine. 2017;23(5):623–630. doi: 10.1038/nm.4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ukropec J., Anunciado R.P., Ravussin Y., Hulver M.W., Kozak L.P. UCP1-independent thermogenesis in white adipose tissue of cold-acclimated Ucp1-/- mice. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(42):31894–31908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang Y., Berry D.C., Graff J. Distinct cellular and molecular mechanisms for beta3 adrenergic receptor induced beige adipocyte formation. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.30329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.