Abstract

This paper exploits Social Security law changes to identify the effect of Social Security income on the use of formal and informal home care by the elderly. Results from an instrumental variables estimation strategy show that as retirement income increases, elderly individuals increase their use of formal home care and become less likely to rely on informal home care provided to them by their children. This negative effect on informal home care is most likely driven by male children withdrawing from their caregiving roles. The empirical results also suggest that higher Social Security benefits would encourage the use of formal home care by those who would not have otherwise used any type of home care and would also encourage the use of both types of home care services among elderly individuals.

Keywords: Social Security, Retirement income, Long-term care, Formal home care, Informal home care

1. Introduction

Social Security is the primary source of income for the retired and has played a vital role in reducing poverty among the elderly. In 2010, 53% of beneficiary couples and 74% of unmarried beneficiaries received at least 50% of their income from Social Security (Fast Facts & Figures About Social Security, 2012). Based on the March 2011 Current Population Survey (CPS), the poverty rate among the elderly aged 65 and over would be 35 percentage points higher if Social Security income was not taken into account (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2012). Clearly, changes in Social Security benefits would affect the elderly in many ways.

The solvency of Social Security has been a major concern among policymakers. The issue has attracted growing attention, as the weak economy causes contributions to decline and about 10,000 baby boomers reach retirement age every day. According to the 2013 Social Security Trustees Report, Social Security trust funds will exhaust in 2033, and after 2033, it will pay about 75% of promised benefits. Advocates of Social Security reform have proposed several ways to increase revenue and reduce retirement benefits. Some examples include increasing the full retirement age, lifting the payroll tax cap, and reducing the annual cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs). Critics of the reform, however, argue that these changes may negatively affect the well-being of the beneficiaries.

The goal of the paper is to investigate the effect of Social Security benefits on the retired. There is a serious econometric issue, however: the amount of Social Security payment depends on the beneficiary’s earnings history, which is likely to correlate with unobserved characteristics that associate with the outcomes of interest. To address the endogeneity issue, I exploit exogenous variations in Social Security payment created by two legislation changes in 1972 and 1977 (i.e., Social Security notch). In 1972, Congress passed a law to provide automatic COLAs to ensure that Social Security benefits would keep up with inflation. The formula designed to calculate the benefits, however, was flawed and caused Social Security benefits to rise faster than inflation. A major element of the 1977 law change was to correct the formula. The new rules, however, only applied to those who were age 60 and younger in 1977 (i.e., individuals born in 1917 or later), workers nearing retirement in 1977 (i.e,. individuals born during 1910–1916) were able to retain the more generous benefits calculated under the 1972 amendments. These law changes created permanent differences in Social Security benefits for retirees who were otherwise similar but born in different years.

A number of studies have exploited the exogenous variations in Social Security income to study the impact on a variety of outcomes and their results consistently suggest that treating Social Security income as exogenous would create biased estimates. Krueger and Pischke (1992) look at the retirement decision of the elderly. Using the CPS data from 1976 to 1988, they find that decreases in Social Security payments resulting from the 1977 amendments reduce rewards for remaining in the labor force and lead to early retirement. Using the 1980–1999 CPS data, Engelhardt et al. (2005) find that the likelihood of living with others decreases with Social Security income. The estimated elasticity is −0.4 for all elderly and the response is considerably greater for elderly widows and divorcees (i.e., −1.4). Similarly, Engelhardt (2008) find that the rise in Social Security benefits explains increases in elderly homeownership over the last twenty-five years. Snyder and Evans (2006) examine the link between income and mortality and their findings show that those born in 1916 have higher mortality than those born in 1917 even though the older cohort receives higher Social Security benefits. Using data from the 1993 wave of the Assets and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD), Moran and Simon (2006) find the use of prescription drugs by low education or low income households is a normal good and is highly income sensitive. The most recent study in the literature, and the analysis closest in methodology and contents to the current study, is conducted by Goda et al. (2011). Goda et al. (2011) use data from the 1993 and 1995 waves of the AHEAD to estimate the effect of Social Security income on the long-term care utilization of the elderly. They focus on households in which the primary beneficiary has less than a high school education and find suggestive evidence that retirees substitute formal home care (i.e., paid home care services) for nursing home utilization as their Social Security income increases (i.e., an additional $1000 of household Social Security payment leads to a 3.1 percentage point increase in formal home care, and a 2.8 percentage point decrease in the use of nursing home).1

Like Goda et al. (2011), this study uses Social Security law changes to identify the causal effect of retirement income on the use of long-term care services by the elderly. However, unlike Goda et al. (2011) that focus on low educated seniors and on the use of formal home care and nursing home, I use a nationally representative sample to investigate the use of formal home care and informal home care provided freely by family or friends.2 Informal home care has become prevalent due to population aging and high costs of long-term care services. In this paper, I focus exclusively on the informal home care provided by children and examine how the parent’s retirement income influences the caregiving behavior of the adult child. I also look at whether there is a substitution between formal and informal home care due to changes in Social Security income. To my knowledge, this is the first study to examine the causal relationship between retirement income and the use of informal home care services by the elderly.3

In recent years, state and federal lawmakers have recognized the important role of family caregivers in the long-term care system and have regarded informal care as a way to reduce public long-term care expenditures. Several states have offered tax deductions and credits for family caregivers. For example, Georgia offers a credit of up to $150 for a qualifying family member. California and Missouri offer $500 tax credit for full-time caregivers. In New Jersey, a $675 tax credit has been proposed. At the national level, the National Family Caregiver Support Program was established in 2000 and it has provided approximately $154 million annually to support family or informal caregivers. Determining the impact of Social Security income on informal home care and on the substitution between formal and informal home care has important implications for developing Social Security reform and long-term care policies.

I use data from the Second Longitudinal Study of Aging (LSOA II) and an instrumental variables method to identify the effect of an exogenous change in Social Security benefits on the elderly. Although I find a negative effect of Social Security income on the use of informal home care, the estimated effect does not reach statistical significance. Social Security income, however, has a statistically significant negative impact on the use of informal home care provided by the adult child (i.e., the income elasticity is −2.2 at the sample means) and this negative effect is likely driven by male children withdrawing from their caregiving role. Moreover, the findings suggest that the use of formal home care is a normal good and is highly income sensitive. Specifically, a $1000 increase in household Social Security income would significantly increase the likelihood of utilizing formal home care by 2.1 percentage points. Although some elderly individuals may substitute formal for informal home care in response to higher retirement income, the estimated effects suggest that increases in retirement income would encourage elderly individuals to use both paid and unpaid helpers and also encourage the use of home care services among those who would not have otherwise used any type of home care services. Finally, the subsample analysis shows a smaller income effect among married, nonwhite or low-educated elderly individuals.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a brief discussion of the background of the legislation changes during the 1970s; Section 3 provides a detailed discussion of the LSOA II data and the empirical strategy; Section 4 presents the estimation results for the full sample as well as for various subsamples of interest; and Section 5 concludes.

2. Double indexation and the Social Security notch

Prior to 1972, Social Security benefits were based on workers’ average nominal monthly earnings and were calculated using a progressive formula. The benefit amount was fixed and Congress had to amend the Social Security law in order to make adjustments to the payments. During the 1960s and 1970s, inflation erosion of Social Security payments became a serious concern as inflation had more than tripled to about five percent per year. In order to keep pace with inflation, Congress had enacted several large increases in benefit amount during the period and in 1972, Congress changed the Social Security law to automatically index the growth of benefits to inflation based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI). However, the formula used to convert past earnings into current dollars was flawed, causing benefits to increase faster than inflation rate, a situation commonly referred to as double indexation. The double indexation error imposed a serious financial burden on the Social Security system, and thus in 1977, Congress passed a law to correct the formula and eliminated double indexation. The law change substantially reduced Social Security payments. It required a five year transition period to avoid abrupt changes in benefits for workers who were approaching retirement. The lower payment took effect each year, but only for those who were eligible for retirement after the new law became effective in 1979 (i.e., those born in 1917 or later). Retirees born between 1910 and 1916 were able to retain the benefit level under the 1972 amendments. As a result, the cohorts born in 1917 or later would receive benefits that were far less generous than the preceding cohorts.4 The legislation changes are unanticipated to retirees and create permanent differences in Social Security benefits among adjacent cohorts with similar earnings history. Using these policy experiments, I am able to estimate the impact of Social Security income freed from individual attributes and other factors unobserved in the data.5

3. Data and empirical strategy

The sample is constructed from the Second Longitudinal Study of Aging (LSOA II), which was a nationally representative, longitudinal survey that was conducted as a supplement to the 1994 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). The baseline sample of the LSOA II was drawn from respondents who participated in the 1994 NHIS, including 9,443 civilian noninstitutionalized individuals aged 70 and over in 1995 (i.e., born prior to 1926). Two follow-up surveys were conducted in 1996–1997 and 1999–2000. The LSOA II provides detailed information regrading health care utilization and the physical and social well-being of the elderly, including home care and medical care use, health status, living arrangements and the caregiving behavior of their children. Most importantly, for our purposes, information on Social Security income is also available through the NHIS Family Resources Supplement (FRS).

The FRS asks a series of questions regarding Social Security income. I focus on two questions asking Social Security income received at the individual level. The first question reads “Social Security/railroad retirement by person?” For respondents who replied “Yes” to the question, the survey subsequently asks the dollar amount received monthly. With the response to the second question I am able to study the effect of a marginal increase in Social Security income on a variety of outcomes of the elderly. Unfortunately, this question was only asked through the 1996 wave of the NHIS. Thus, this study will be constrained to only using the LSOA II data conducted in the base year.

Although data in the LSOA II are at the individual level, I measure Social Security income at the household level as the majority of the sample is made up of two-person households (52%) and they are likely to pool resources together as they make consumption or other important decisions.6

The key to determine whether household Social Security income is affected by double indexation is to identify the birth year of the primary beneficiary in the household. Most married women in these birth cohorts are likely to receive Social Security benefits based on their husband’s earnings history. Thus, following previous studies (Engelhardt et al., 2005, 2008; Goda et al., 2011; Moran and Simon, 2006), I designate the male member as the primary beneficiary in a household. For households without a male member, I designate the never-married female as the primary beneficiary for households consisting of a never-married female and the deceased/former husband as the primary beneficiary for households consisting of a widowed/divorced female. Unfortunately, the birth year of the deceased/former husband is not available in the LSOA II. I impute this information by subtracting three years from the widowed/divorced female’s birth year as three years were found to be the median spousal age difference for widowed/divorced elderly (Engelhardt et al., 2005).

Although 9447 elderly individuals are included in the base year of LSOA II, I do not use all of these observations in the baseline sample because of the following restrictions that I impose: First, interviews of the base year sample were conducted during 1994–1996. I exclude respondents interviewed in 1996 because information on Social Security income was collected in 1994 (i.e., excluding 1058 respondents). Following previous studies, I exclude respondents with imputed Social Security income (i.e., excluding 639 respondents) and with household Social Security income less than $100 per month (i.e., excluding 368 respondents). I also restrict the sample to individuals in households in which the primary Social Security beneficiary was born in 1900 or later (i.e., excluding 90 respondents). With a minimum age limit of 70 in the LSOA II, individuals included in the sample were those born between 1900 and 1925. Finally, I restrict the sample to Medicare-insured seniors (i.e., excluding 159 respondents). After excluding observations with missing values for the chosen set of control variables that I describe below, a final sample of 6836 individuals remains.

In this paper I am interested in estimating the effect of Social Security income on the elderly. To estimate the effect, I use the following specification,

| (1) |

where Yi represents outcomes of respondent i, SSi represents annual household Social Security income (measured in thousands), Xi is a vector of control variables that include the characteristics of the respondent listed in Table 1, and εi is the error term.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

| Full | 1911–1917 cohorts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| N = 6836 | Yes N = 2426 |

No N = 4410 |

||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Mean | Std. dev. | Mean | Std. dev. | Mean | Std. dev. | |

| Outcome variables | ||||||

| Formal home care | 0.106 | 0.308 | 0.117 | 0.322 | 0.099 | 0.299 |

| Informal home care | 0.252 | 0.434 | 0.253 | 0.435 | 0.252 | 0.434 |

| Informal home care, child/children | 0.488 | 0.500 | 0.449 | 0.498 | 0.509 | 0.500 |

| Informal home care, daughter | 0.344 | 0.475 | 0.325 | 0.469 | 0.354 | 0.478 |

| Informal home care, son | 0.196 | 0.397 | 0.177 | 0.382 | 0.206 | 0.405 |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Social Security income (thousands) | 10.160 | 4.733 | 10.707 | 5.025 | 9.857 | 4.536 |

| Age | 77 | 5 | 78 | 3 | 76 | 6 |

| Age squared | 5964 | 854 | 6134 | 456 | 5871 | 997 |

| Age cubed | 464,080 | 101,798 | 481,363 | 53,631 | 454,533 | 119,347 |

| Male | 0.407 | 0.491 | 0.344 | 0.475 | 0.442 | 0.497 |

| Married | 0.512 | 0.500 | 0.483 | 0.500 | 0.528 | 0.499 |

| White | 0.913 | 0.282 | 0.914 | 0.280 | 0.912 | 0.283 |

| Hispanic | 0.038 | 0.190 | 0.039 | 0.193 | 0.037 | 0.189 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 0.391 | 0.488 | 0.413 | 0.493 | 0.378 | 0.485 |

| High school | 0.353 | 0.478 | 0.363 | 0.481 | 0.347 | 0.476 |

| Some college | 0.210 | 0.407 | 0.187 | 0.390 | 0.223 | 0.416 |

| College | 0.071 | 0.257 | 0.058 | 0.234 | 0.079 | 0.269 |

| Post college | 0.046 | 0.210 | 0.036 | 0.187 | 0.052 | 0.222 |

| Size of the household | 1.849 | 1.022 | 1.771 | 0.852 | 1.892 | 1.103 |

| Number of living sons | 1.350 | 1.371 | 1.373 | 1.420 | 1.336 | 1.343 |

| Number of living daughters | 1.341 | 1.384 | 1.361 | 1.386 | 1.331 | 1.382 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 0.220 | 0.414 | 0.233 | 0.423 | 0.213 | 0.410 |

| Midwest | 0.268 | 0.443 | 0.263 | 0.441 | 0.271 | 0.444 |

| South | 0.318 | 0.466 | 0.314 | 0.464 | 0.320 | 0.467 |

| West | 0.194 | 0.396 | 0.190 | 0.393 | 0.196 | 0.397 |

| MSA size | ||||||

| Non-MSA | 0.290 | 0.454 | 0.299 | 0.458 | 0.284 | 0.451 |

| 1,000,000 or more | 0.365 | 0.481 | 0.360 | 0.480 | 0.367 | 0.482 |

| 250,000–999,999 | 0.264 | 0.441 | 0.263 | 0.441 | 0.264 | 0.441 |

| 100,000–249,999 | 0.061 | 0.239 | 0.059 | 0.235 | 0.062 | 0.241 |

| Under 100,000 | 0.021 | 0.143 | 0.018 | 0.134 | 0.022 | 0.147 |

Summary statistics are weighted using the Final Annual LSOA II weight.

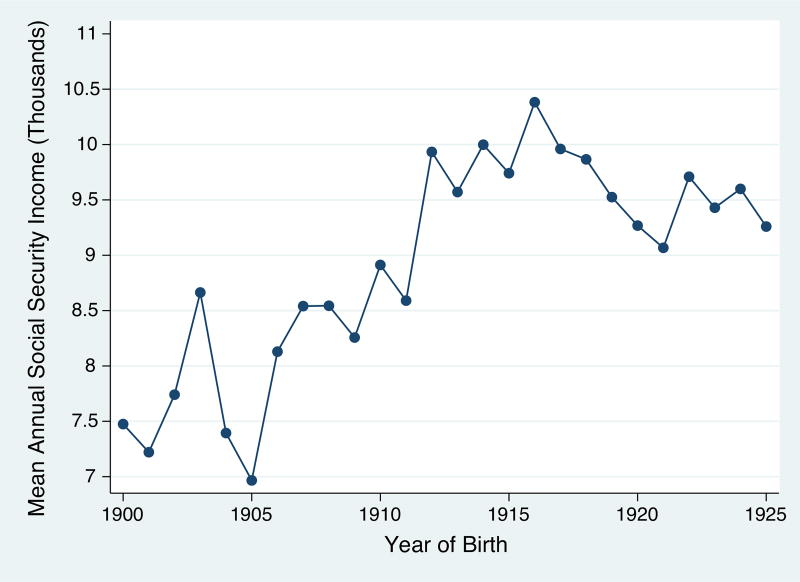

The coefficient of interest is α1, which represents the effect of Social Security income on the outcomes of interest. The estimation of Eq. (1), however, is problematic due to the potential endogeneity of Social Security benefits, SSi. The amount of benefits is based on the earnings history of the primary beneficiary, which is likely to correlate with unobserved variables that are associated with outcomes. For example, studies have found that Social Security benefits may crowd out private saving and thus are likely to be negatively associated with wealth accumulation (Beach et al., 1984; Feldstein, 1974; Feldstein and Pellechio, 1979). If information on wealth is not available, the estimate of formal home care services would bias downward and the estimate of informal home care would bias upward as beneficiaries with more financial resources are more likely to use formal home care while they are less likely to use informal home care. To overcome the endogeneity problem, I use an instrumental variables approach based on the legislative changes in 1972 and 1977. As I described above, the 1972 amendments overindexed wages for inflation and resulted in an unintended windfall for retired workers born between 1910 and 1916. Thus, Social Security benefits, SSi, are expected to be higher among respondents in households in which the primary beneficiary was born during this period. Fig. 1 displays mean annual household Social Security income by the birth year of the primary beneficiary. The figure clearly shows that benefit levels are noticeably higher among the 1910–1916 cohorts and fall steadily for the following cohorts (as a result of the 1977 amendments). In this study, I exploit these exogenous variations in Social Security income to identify its effect on various outcomes of the elderly. Specifically, I form an instrumental variable, Zi, that takes the value of 1 if respondent i is in a household in which the primary Social Security beneficiary was born during the years of 1911–1917, and zero if the primary beneficiary was born in other years between 1900 and 1925.7 I choose the years 1911–1917 because these birth cohorts benefit the most from double indexation.8 The first stage regression is written as

| (2) |

where Zi is the instrument and Xi is the vector of controls listed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Social Security income by year of birth. The figure plots the mean annual household Social Security income by the birth year of the primary Social Security beneficiary. Benefits for retirees born in 1910–1916 are calculated based on the 1972 Social Security amendments and benefits for retirees born in 1917 and after are calculated based on the 1977 Social Security amendments.

The identifying assumption is that the instrument, Zi, only affects outcomes indirectly through its effect on Social Security income, SSi, and therefore, is not correlated with any unobserved variables that affect the outcomes of the elderly (the residual in Eq. (1)).

Table 1 lists summary statistics for the full sample of respondents. I also break down the summary statistics by whether the primary beneficiary was born in 1911–1917. The top panel of Table 1 lists the summary statistics of outcome variables, including the use of formal and informal home care services (i.e., the use of paid and unpaid helpers to help with ADLs/IADLs limitations).9,10 I further examine the caregiving behavior of children by generating three indicator variables for whether informal home care is provided by children, daughters, and sons, respectively. The summary statistics of control variables are listed in the bottom panel of Table 1. Note that all analyses presented in this paper are weighted using the Final Annual LSOA II weight.

In the full sample, the mean annual household Social Security income is $10,160. Approximately 11% of respondents reported to use paid helpers and about 25% used unpaid helpers for ADLs/IADLs limitations. Of the 1,737 respondents who used informal home care, about 49% reported that the care was given by the child (children). There is a significant difference in the caregiving behavior between daughters and sons. Consistent with previous studies (McGarry, 1999; Wolf et al., 1997), I find that daughters are considerably more likely to provide informal home care for the parent relative to sons, 34% versus 20%. Consistent with Fig. 1, household Social Security income is higher for the 1911–1917 cohort. These cohorts are also more likely to use formal home care services. Moreover, children, regardless of gender, are less likely to provide informal home care for the parent if the parent’s Social Security benefit is calculated based on the 1972 amendments. There are also notable differences in other attributes across these two groups. For example, the 1911–1917 cohorts have lower education and are less likely to be male or married. Of course, these numbers are simply raw averages, and should be treated with caution in light of the endogeneity issues discussed above.

4. Results

Tables 2 and 3 present the estimated effects of Social Security income on the use of formal and informal home care and the caregiving behavior of children, respectively. In the first column of each table, I present the reduced form estimation, which includes the indicator variable for individuals in households in which the primary beneficiary was born in 1911–1917 directly in Eq. (1) rather than estimating two stages. This basically estimates differences in outcomes between respondents whose Social Security income is affected by double indexation and respondents whose Social Security income is not affected. In the second column of the tables, I present results from estimating an OLS specification (without instrumenting for Social Security income). These estimates are subject to the endogeneity concerns that I discussed above. In the third column, I report the results from instrumenting for Social Security income. These IV estimates directly address the potential endogeneity of Social Security income. Note that standard errors reported in the tables are clustered at the birth year of the respondent.

Table 2.

Effect of Social Security income on formal and informal home care utilization.

| Formal home care | Informal home care | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| (1) Reduced-form |

(2) OLS |

(3) IV |

(1) Reduced-form |

(2) OLS |

(3) IV |

|

| Social Security income (thousands) | −0.002** (0.001) | 0.021** (0.009) | −0.006*** (0.001) | −0.005 (0.015) | ||

| Elasticity | [−0.192] | [2.018] | [−0.242] | [−0.202] | ||

| Indicator for the 1911–1917 cohorts | 0.016** (0.007) | −0.004 (0.012) | ||||

| Age | −0.143 (0.280) | −0.012 (0.301) | −0.423 (0.303) | 0.677 (0.457) | 0.764 (0.450) | 0.746 (0.541) |

| Age squared | 0.001 (0.004) | −0.000 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) | −0.009 (0.006) | −0.010* (0.006) | −0.010 (0.007) |

| Age cubed | −0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | 0.000* (0.000) | 0.000* (0.000) | 0.000* (0.000) |

| Male | −0.041*** (0.009) | −0.043*** (0.009) | −0.040*** (0.010) | −0.095*** (0.012) | −0.095*** (0.012) | −0.095*** (0.012) |

| Married | −0.047*** (0.010) | −0.037*** (0.010) | −0.140*** (0.040) | −0.024 (0.016) | 0.004 (0.018) | −0.001 (0.073) |

| White | −0.014 (0.012) | −0.011 (0.012) | −0.039** (0.018) | −0.050 (0.031) | −0.042 (0.030) | −0.044 (0.028) |

| Hispanic | −0.036** (0.017) | −0.038** (0.017) | −0.011 (0.021) | −0.047 (0.030) | −0.054* (0.029) | −0.053* (0.032) |

| Education | ||||||

| High school | 0.006 (0.011) | 0.009 (0.011) | −0.017 (0.015) | −0.083*** (0.011) | −0.076*** (0.011) | −0.078*** (0.019) |

| Some college | 0.026* (0.013) | 0.028** (0.013) | 0.002 (0.015) | −0.100*** (0.022) | −0.093*** (0.022) | −0.094*** (0.030) |

| College | −0.012 (0.018) | −0.011 (0.017) | −0.022 (0.021) | −0.026 (0.027) | −0.023 (0.026) | −0.023 (0.023) |

| Post college | 0.039* (0.019) | 0.042** (0.020) | 0.002 (0.019) | −0.127*** (0.024) | −0.116*** (0.023) | −0.118*** (0.032) |

| Size of the household | −0.017*** (0.003) | −0.017*** (0.003) | −0.018*** (0.003) | 0.049*** (0.008) | 0.049*** (0.008) | 0.049*** (0.008) |

| Number of living sons | 0.006*** (0.002) | 0.006*** (0.002) | 0.006*** (0.002) | 0.006 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) |

| Number of living daughters | −0.005* (0.002) | −0.005* (0.002) | −0.003 (0.003) | 0.012*** (0.004) | 0.011** (0.004) | 0.011*** (0.004) |

| Region | ||||||

| Midwest | −0.012 (0.013) | −0.012 (0.013) | −0.011 (0.014) | 0.011 (0.016) | 0.011 (0.016) | 0.011 (0.016) |

| South | −0.006 (0.010) | −0.008 (0.010) | 0.009 (0.014) | 0.009 (0.016) | 0.005 (0.015) | 0.006 (0.020) |

| West | −0.011 (0.012) | −0.012 (0.012) | −0.001 (0.015) | −0.018 (0.016) | −0.021 (0.016) | −0.021 (0.018) |

| MSA size | ||||||

| 1,000,000 or more | 0.013 (0.008) | 0.014* (0.008) | −0.009 (0.012) | 0.012 (0.013) | 0.019 (0.013) | 0.018 (0.018) |

| 250,000–999,999 | −0.016 (0.012) | −0.015 (0.012) | −0.033*** (0.011) | 0.018 (0.015) | 0.023 (0.015) | 0.022 (0.019) |

| 100,000–249,999 | 0.021 (0.017) | 0.021 (0.017) | 0.014 (0.015) | 0.032 (0.025) | 0.034 (0.024) | 0.034 (0.024) |

| Under 100,000 | −0.002 (0.022) | −0.003 (0.022) | −0.011 (0.026) | −0.010 (0.026) | −0.008 (0.025) | −0.008 (0.024) |

| Constant | 4.721 (7.357) | 0.929 (7.924) | 12.306 (8.078) | −16.558 (12.126) | −18.924 (11.907) | −18.414 (14.503) |

| First-stage coefficient on IV | 0.784*** (0.159) | 0.784*** (0.159) | ||||

| F-statistics on notch indicator | 24.32 | 24.32 | ||||

| F-statistics for weak IV test | 44.98 | 44.98 | ||||

| Observations | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 |

All regressions are weighted using the Final Annual LSOA II weight. Robust standard errors are listed in parenthesis and are clustered at the birth year of the respondent. The endogenous variable of interest is Social Security income, and the instrument is an indicator variable for respondents in households in which the primary beneficiary was born during 1911–1917. The elasticity with respect to Social Security income is calculated at the means of dependent variables and Social Security income of the sample.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 10% level.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 5% level.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 1% level.

Table 3.

Effect of Social Security income on the caregiving behavior of children.

| Informal home care, child/children | Informal home care, daughters | Informal home care, sons | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| (1) Reduced-form |

(2) OLS |

(3) IV |

(1) Reduced-form |

(2) OLS |

(3) IV |

(1) Reduced-form |

(2) OLS |

(3) IV |

|

| Social Security income (thousands) | −0.003*** (0.001) | −0.027** (0.013) | −0.002*** (0.001) | −0.011 (0.010) | −0.002** (0.001) | −0.019** (0.009) | |||

| Elasticity | [−0.248] | [−2.230] | [−0.234] | [−1.285] | [−0.415] | [−3.940] | |||

| Indicator for the 1911–1917 cohorts | −0.021** (0.009) | −0.009 (0.008) | −0.015** (0.007) | ||||||

| Age | −0.025 (0.373) | −0.092 (0.386) | 0.339 (0.377) | 0.291 (0.357) | 0.281 (0.368) | 0.436 (0.334) | −0.630*** (0.203) | −0.686*** (0.229) | −0.378* (0.208) |

| Age squared | −0.000 (0.005) | 0.001 (0.005) | −0.005 (0.005) | −0.004 (0.005) | −0.004 (0.005) | −0.006 (0.004) | 0.008*** (0.003) | 0.008*** (0.003) | 0.005* (0.003) |

| Age cubed | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | −0.000*** (0.000) | −0.000*** (0.000) | −0.000* (0.000) |

| Male | −0.069*** (0.010) | −0.068*** (0.010) | −0.070*** (0.010) | −0.048*** (0.009) | −0.048*** (0.008) | −0.049*** (0.008) | −0.030*** (0.006) | −0.028*** (0.005) | −0.030*** (0.006) |

| Married | −0.130*** (0.011) | −0.117*** (0.012) | −0.008 (0.060) | −0.103*** (0.008) | −0.094*** (0.008) | −0.054 (0.046) | −0.047*** (0.007) | −0.040*** (0.008) | 0.038 (0.043) |

| White | −0.019 (0.022) | −0.015 (0.022) | 0.014 (0.027) | −0.004 (0.015) | −0.001 (0.015) | 0.010 (0.020) | −0.007 (0.015) | −0.005 (0.015) | 0.016 (0.020) |

| Hispanic | −0.042* (0.021) | −0.046** (0.021) | −0.074*** (0.024) | −0.021 (0.019) | −0.023 (0.019) | −0.034 (0.021) | −0.037*** (0.013) | −0.039*** (0.013) | −0.059*** (0.015) |

| Education | |||||||||

| High school | −0.045*** (0.008) | −0.042*** (0.008) | −0.015 (0.017) | −0.035*** (0.009) | −0.032*** (0.009) | −0.022 (0.015) | −0.014** (0.007) | −0.013* (0.007) | 0.007 (0.012) |

| Some college | −0.072*** (0.015) | −0.067*** (0.015) | −0.039** (0.018) | −0.058*** (0.012) | −0.055*** (0.012) | −0.045** (0.017) | −0.022* (0.012) | −0.019 (0.012) | 0.001 (0.015) |

| College | −0.000 (0.012) | 0.001 (0.012) | 0.012 (0.012) | −0.000 (0.009) | 0.001 (0.008) | 0.005 (0.009) | −0.001 (0.009) | −0.000 (0.009) | 0.007 (0.010) |

| Post college | −0.051*** (0.015) | −0.045*** (0.015) | −0.002 (0.024) | −0.050*** (0.012) | −0.046*** (0.012) | −0.031 (0.019) | −0.007 (0.013) | −0.003 (0.013) | 0.027 (0.019) |

| Size of the household | 0.048*** (0.007) | 0.048*** (0.007) | 0.049*** (0.007) | 0.040*** (0.006) | 0.040*** (0.006) | 0.040*** (0.006) | 0.013*** (0.004) | 0.013*** (0.004) | 0.014*** (0.004) |

| Number of living sons | 0.014*** (0.003) | 0.013*** (0.003) | 0.013*** (0.003) | −0.006** (0.003) | −0.006** (0.003) | −0.006** (0.003) | 0.026*** (0.004) | 0.026*** (0.004) | 0.026*** (0.004) |

| Number of living daughters | 0.030*** (0.004) | 0.029*** (0.004) | 0.027*** (0.004) | 0.041*** (0.005) | 0.040*** (0.005) | 0.040*** (0.005) | −0.004 (0.003) | −0.004 (0.003) | −0.005 (0.003) |

| Region | |||||||||

| Midwest | 0.001 (0.010) | 0.001 (0.009) | 0.000 (0.010) | 0.014 (0.010) | 0.014 (0.009) | 0.013 (0.010) | −0.012 (0.008) | −0.012 (0.008) | −0.012 (0.008) |

| South | −0.010 (0.011) | −0.012 (0.011) | −0.030** (0.015) | 0.007 (0.010) | 0.006 (0.010) | −0.001 (0.013) | −0.012 (0.007) | −0.013* (0.007) | −0.026*** (0.008) |

| West | −0.032*** (0.010) | −0.033*** (0.010) | −0.045*** (0.013) | −0.025*** (0.009) | −0.026*** (0.009) | −0.030** (0.012) | −0.008 (0.007) | −0.009 (0.007) | −0.017** (0.008) |

| MSA size | |||||||||

| 1,000,000 or more | 0.007 (0.008) | 0.011 (0.008) | 0.036** (0.015) | 0.003 (0.008) | 0.006 (0.008) | 0.015 (0.011) | 0.005 (0.006) | 0.007 (0.006) | 0.025* (0.013) |

| 250,000 – 999,999 | −0.005 (0.009) | −0.002 (0.010) | 0.017 (0.013) | −0.016 (0.010) | −0.014 (0.010) | −0.007 (0.011) | 0.003 (0.006) | 0.005 (0.006) | 0.019** (0.009) |

| 100,000–249,999 | 0.039** (0.018) | 0.041** (0.019) | 0.048** (0.021) | 0.019 (0.014) | 0.020 (0.015) | 0.023 (0.016) | 0.017 (0.014) | 0.018 (0.014) | 0.023 (0.015) |

| Under 100,000 | −0.004 (0.024) | −0.001 (0.023) | 0.007 (0.025) | 0.008 (0.023) | 0.009 (0.023) | 0.012 (0.023) | 0.023 (0.020) | 0.025 (0.019) | 0.031 (0.020) |

| Constant | 1.563 (9.808) | 3.603 (10.148) | −8.306 (9.983) | −6.902 (9.355) | −6.528 (9.646) | −10.834 (8.780) | 16.724*** (5.298) | 18.398*** (6.014) | 9.877* (5.548) |

| Observations | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 |

All regressions are weighted using the Final Annual LSOA II weight. Robust standard errors are listed in parenthesis and are clustered at the birth year of the respondent. The endogenous variable of interest is Social Security income, and the instrument is an indicator variable for respondents in households in which the primary beneficiary was born during 1911–1917. The elasticity with respect to Social Security income is calculated at the means of dependent variables and Social Security income of the sample.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 10% level.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 5% level.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 1% level.

The coefficient estimates on the indicator variable in columns (1) of Table 2 suggest that individuals in households in which the primary beneficiary was born in 1911–1917 are about 1.6 percentage points more likely to use formal home care and are approximately 0.4 percentage point less likely to use informal home care compared to individuals in households in which the primary beneficiary was born in adjacent years. The estimated effect on informal home care, however, is not precisely estimated. According to the OLS estimates reported in columns (2), Social Security income has a statistically significant negative effect on both formal and informal home care utilization. The estimates show that an additional $1000 of annual Social Security benefit would reduce the probability of using formal and informal home care by approximately 0.2 and 0.6 percentage points, respectively.

The IV estimates reported in columns (3), however, reveal evidence that Social Security income has a significant effect on the probability of using formal home care services. The results from the first stage indicate that the correlation between the instrument and Social Security income is positive, as expected, and it is highly statistically significant. Social Security income is approximately $780 higher if the primary beneficiary was born in 1911–1917. This is consistent with the pattern in Fig. 1. The first stage F-statistic on the instrument is equal to 24.32 and the F-statistic from the first stage regression (44.98) is significantly above the critical value (16.38) obtained from the Stock and Yogo (2005) test for weak instruments using limited information maximum likelihood estimation (assuming a 10 percent size threshold). According to the estimated marginal effect, a $1000 increase in annual Social Security income raises the probability of using formal home care by about 2.1 percentage points. Evaluated at the mean levels of formal home care utilization and Social Security income in the sample, this translates into an income elasticity of approximately 2.0, suggesting that paid home care services are a normal good and are highly sensitive to income.11 Moreover, consistent with the descriptions above, treating Social Security income as exogenous would produce a serious downward bias, leading to an underestimation of the positive effect of Social Security income on formal home care utilization.

The coefficient estimates associated with the control variables indicate that male respondents are significantly less likely to use any form of home care services and married respondents are less likely to use formal home care. As expected, the size of household has a statistically significant negative impact on the probability of using formal home care while its effect on the utilization of informal home care is positive and is statistically significant at the 1% level. The likelihood of using informal home care is lower among elderly individuals with higher educational levels. Interestingly, I find a distinct difference in the effect of daughters and sons on the utilization of formal and informal home care of the parent. The number of living sons is positively correlated with the parent’s probability of using paid helpers while the number of living daughters is positively associated with the use of informal home care of the parent. These estimated effects are statistically significant at the 1% level regardless of the estimation method. Due to these findings, I further examine the effect of Social Security income on the caregiving behavior of children and the results are presented in Table 3.

The dependent variables in Table 3 are three dummy variables equal to one if informal home care is provided by children, daughters, and sons, respectively and zero otherwise. The OLS estimates, reported in columns (2), suggest that an increase in Social Security benefits would significantly reduce the probability of using informal home care provided by the adult child regardless of the child’s gender. When instrumenting for Social Security income, the magnitude of the negative effect and the income elasticities increase considerably. The IV estimates show that a $1000 increase in annual Social Security payments would reduce the probability of utilizing informal home care provided by children, daughters, and sons by approximately 2.7, 1.1, and 1.9 percentage points, respectively. Moreover, the estimated effects on children and sons are statistically significant at the 5% level and are economically meaningful. The income elasticities, measured at the means of the sample, are approximately −2.2 and −3.9 for the care provided by children and sons, respectively. These results provide suggestive evidence that informal home care provided by children is an inferior good and is highly income sensitive among the elderly. Moreover, the results indicate that in response to increases in the retirement income of the parent, sons are more likely to withdraw from taking care of the parent compared to daughters. Unfortunately, due to data limitations, I am not able to detect the mechanism behind the reduction in informal home care provided by children (e.g. whether the parent or the child is the main decision maker). One possible explanation for the finding is that women has played a main role in providing informal home care (Carmichael and Charles, 1998) and the opportunity costs associated with eldercare responsibility is higher for men compared to women (Carmichae and Charles, 2003). Finally, consistent with the notion above, the estimated effect of Social Security benefits on informal home care provided by children would be underestimated if Social Security income is treated as an exogenous variable.

4.1. Formal versus informal home care

Overall, the results provide evidence that in response to increases in Social Security income elderly individuals are significantly more likely to use formal home care services and are less likely to rely on home care provided by children. In this section, I attempt to identify the mechanism behind these findings. Specifically, I ask whether the increase in formal home care utilization comes from individuals substituting away from informal home care or comes from seniors who would not have utilized home care services are more likely to hire paid helpers due to higher Social Security payments. I divide elderly individuals into six categories based on their home care utilization and the source of informal home care: no home care use, using only formal home care, using only informal home care provided by children, using only informal home care provided by sources other than children, using both formal and informal home care provided by children, and using both formal and informal home care provided by other sources.12 The estimates are obtained using a multinomial logit model with the two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI) to address the endogeneity of Social Security income (Terza et al., 2008).13 The results are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effect of Social Security income on home care services utilization.

| Coefficient | Mean marginal effect |

|

|---|---|---|

| No home care use | −0.023 (0.017) | |

| Formal home care use only | 0.217 (0.191) | 0.008 (0.009) |

| Informal home care by children only | 0.061 (0.186) | 0.001 (0.014) |

| Informal home care by sources other than children only | −0.051 (0.149) | −0.009 (0.013) |

| Formal and informal home care by children | −0.080 (0.214) | −0.004 (0.005) |

| Formal and informal home care by other sources | 1.006*** (0.235) | 0.026*** (0.007) |

| Observations | 6836 | 6836 |

Estimation: Two-stage residual inclusion multinomial logit. Base outcome is no home care use. All regressions are weighted using the Final Annual LSOA II weight. The set of covariates in all estimations includes the control variables listed in Table 1. Bootstrapped standard errors clustered at the birth year of the respondent are listed in parenthesis. The endogenous variable of interest is Social Security income. The instrument is an indicator variable for respondents in households in which the primary beneficiary was born during 1911–1917.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 1% level.

The estimated mean marginal effects indicate that a $1000 increase in annual Social Security benefits raises the probability of choosing formal home care only by 0.8 percentage point, while it reduces the probability of no home care use by 2.3 percentage points. As Social Security income increases, the probability of using only informal home care generally decreases. Moreover, I find that an additional $1000 of Social Security benefit would reduce the likelihood of using both formal and informal home care provided by children by 0.4 percentage point. In contrast, it would increase the likelihood of using both formal and informal home care provided by other sources by 2.6 percentage points and the estimated effect is highly statistically significant. These results provide suggestive evidence that although some elderly individuals may substitute formal for informal home care due to higher Social Security payment, the increase in formal home care is likely driven by elderly individuals who would not have otherwise utilized any type of home care services and those who originally use informal home care only but use both paid and unpaid helpers as retirement income increases. These findings also provide some insights into the mechanism behind the finding that Social Security income has a limited impact on the use of overall informal home care, while it has a strong, negative effect on informal home care provided by children. The estimated effects indicate that as retirement income increases, many elderly individuals reported to use both paid and unpaid helpers (other than children). Accordingly, the use of informal home care provided by other sources increases with retirement income. This finding is somewhat consistent with intuition as spouse is listed as the most common unpaid helper in the data and in addition to paid helpers, assistance from family members especially those in the same household is most likely needed in many circumstances.

4.2. Subsample analysis

The effect of Social Security income on the elderly may vary across demographic groups. For example, Engelhardt et al. (2005) note that married couples are likely to have more sources of income and therefore are less likely to rely heavily on Social Security. Thus, their response to changes in Social Security income may be relatively small compared to individuals of other marital types. In this section, I explore whether the effect of Social Security income is sensitive to socio-demographic characteristics of the elderly. To do this, I add an interaction term of Social Security income and the socio-demographic characteristic of interest to the set of control variables in Eq. (1). I focus on three socio-demographic characteristics: marital status (i.e., the respondent is married), race (i.e., nonwhite), and educational attainment (i.e., the respondent has less than a high school education). The results are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Subsample results.

| Formal home care |

Informal home care |

Informal home care, child/children |

Informal home care, daughters |

Informal home care, sons |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Security income (thousands) | 0.059** (0.030) | −0.006 (0.046) | −0.087** (0.040) | −0.039 (0.030) | −0.059** (0.029) |

| SSI* married | −0.054* (0.029) | 0.001 (0.045) | 0.086** (0.039) | 0.039 (0.029) | 0.057** (0.029) |

| Social Security income (thousands) | 0.022** (0.010) | −0.007 (0.016) | −0.030** (0.013) | −0.011 (0.011) | −0.021** (0.009) |

| SSI* nonwhite | −0.015** (0.007) | 0.019 (0.017) | 0.036*** (0.013) | 0.006 (0.010) | 0.029*** (0.009) |

| Social Security income (thousands) | 0.056** (0.028) | −0.051 (0.058) | −0.112* (0.063) | −0.024 (0.035) | −0.087** (0.043) |

| SSI* less than high school | −0.065* (0.037) | 0.085 (0.075) | 0.157* (0.083) | 0.024 (0.049) | 0.127** (0.052) |

| Observations | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 | 6836 |

This table reports results of the estimated effects of Social Security income from three separated estimation equations. The endogenous variables of interest are Social Security income and the interaction terms of Social Security income and the socio-demographic characteristic of interest. The instruments are an indicator variable for respondents in households in which the primary beneficiary was born during 1911–1917 and the interaction terms of a dummy for the beneficiary was born during 1911–1917 and the socio-demographic characteristic of interest. All regressions are weighted using the Final Annual LSOA II weight. The set of covariates in all estimations includes the control variables listed in Table 1. Robust standard errors are listed in parenthesis and are clustered at the birth year of the respondent.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 10% level.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 5%level.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 1% level.

Consistent with the notion in Engelhardt et al. (2005), the magnitude of the estimated effects of Social Security income on all outcomes is smaller for married respondents compared with respondents of other marital types. The estimated differences are statistically significant for the probability of using formal home care and using informal home care provided by children. The finding may be due to that, for married couples, home care responsibility usually falls on the spouse and therefore the income effect on home care would be relatively small for married respondents compared to respondents of other marital types. Compared to white respondents, the estimated effect of Social Security income on the probability of using informal home care provided by children is 3.6 percentage points smaller among nonwhite respondents. The estimated effect is statistically significant at the 5% level and is economically meaningful. For elderly individuals with less than a high school education, the income effect on most outcomes is smaller compared to respondents with at least a high school education and the difference is statistically significant at the 5% level for the outcomes of informal home care provided by sons. This result is in contrast to previous studies that find an economically and statistically greater effect of Social Security income for the less educated (Engelhardt et al., 2005; Goda et al., 2011; Moran and Simon, 2006). Many reasons, such as differences in the study sample and design and in the outcomes of interests, may explain the inconsistency.14 The rationale behind this finding may be that although higher Social Security payments may encourage seniors to use formal home care, and to rely less on informal home care, these options may still be unaffordable for elderly individuals with disadvantaged background and therefore, the impact of Social Security income on the less educated is likely to be smaller.

4.3. Robustness analysis

In this section, I perform several robustness analyses and report the results in Table 6. As mentioned in previous studies, variables regarding health status are potentially endogenous to Social Security income and therefore are excluded from the set of control variables. I include the health-related variables in the estimation equations (i.e., self-rated health and indicator variables for diabetes, bronchitis, asthma, hypertension, and cancer) and the results are robust to the additional controls. The results are also robust to including individuals whose interview was conducted in 1996 and to including individuals who were not Medicare-insured. I also impose various sample restrictions to check the robustness of the results.15 First, I exclude widowed and divorced females to avoid the potential measurement error due to imputing the birth year of the deceased/former husband. Second, I drop individuals in households in which the primary beneficiary was born during the flu years of 1918 and 1919 due to potential correlation between the instrument and the error term in Eq. (1) (e.g., health characteristics). I also restrict the sample to individuals in households in which the primary beneficiary was born in 1910–1920 to avoid the potential cohort effect unrelated to the exogenous variations in Social Security income stemming from the legislation changes. Overall, results are very similar to the baseline estimates. There are some differences worth noting. First, the magnitude of the estimated effect on informal home care provided by children drops substantially and is no longer statistically significant as the widowed and divorced females are excluded from the sample. The finding could be explained by the same reason as I focus on married respondents: informal home care provided by children or other sources may be less important as spouse is likely the one who takes the caregiving responsibility for married couples. Moreover, although the magnitude of the estimated effect on formal home care is similar to the base result, the estimated effect does not attain statistical significance as beneficiaries born in 1918–1919 are excluded and only attains the 10% significant level as the sample is restricted to individuals whose household primary beneficiary was born during 1910–1920.

Table 6.

Robustness analysis.

| Formal home care |

Informal home care |

Informal home care, child/children |

Informal home care, daughters |

Informal home care, sons |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N = 6836) | 0.021** (0.009) | −0.005 (0.015) | −0.027** (0.013) | −0.011 (0.010) | −0.019** (0.009) |

| F-statistics for weak IV test | 44.98 | 44.98 | 44.98 | 44.98 | 44.98 |

| Stock-Yogo critical value (10% LIML size) | 16.38 | 16.38 | 16.38 | 16.38 | 16.38 |

| Add health-related controls (N = 6836) | 0.021** (0.010) | −0.004 (0.015) | −0.026** (0.012) | −0.010 (0.010) | −0.019** (0.008) |

| F-statistics for weak IV test | 42.67 | 42.67 | 42.67 | 42.67 | 42.67 |

| Drop widowed and divorced females (N = 3999) | 0.030*** (0.011) | 0.005 (0.014) | −0.007 (0.009) | 0.003 (0.006) | −0.006 (0.006) |

| F-statistics for weak IV test | 28.67 | 28.67 | 28.67 | 28.67 | 28.67 |

| Drop if the primary beneficiary was born in 1918–1919 (N = 5946) | 0.016 (0.010) | 0.011 (0.013) | −0.022* (0.013) | −0.013 (0.010) | −0.012 (0.009) |

| F-statistics for weak IV test | 53.96 | 53.96 | 53.96 | 53.96 | 53.96 |

| Keep if primary beneficiary was born in 1910–1920 (N = 4025) | 0.021* (0.012) | −0.003 (0.015) | −0.019 (0.012) | −0.004 (0.009) | −0.017** (0.008) |

| F-statistics for weak IV test | 27.76 | 27.76 | 27.76 | 27.76 | 27.76 |

All regressions are weighted using the Final Annual LSOA II weight. The set of covariates in all estimations includes the control variables listed in Table 1. Robust standard errors are listed in parenthesis and are clustered at the birth year of the respondent. The endogenous variable of interest is Social Security income, and the instrument is an indicator variable for respondents in households in which the primary beneficiary was born during 1911–1917.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 10% level.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 5% level.

Corresponds to statistical significance at the 1% level.

Recent studies have suggested that estimation generated from small number of groups may lead to underestimation of standard errors and the typical cluster-robust approach may not be enough to correct the bias. Donald and Lang (2007) proposed using the tG−L distribution, where G is the number of groups and L is the number of regressors that are invariant within groups. In Monte Carlo simulations by Cameron et al. (2008), a t-distribution with G − 2 degrees of freedom works reasonably well in the range of 20 clusters. The 1%, 5%, and 10% critical values for a t24 distribution are about 2.80, 2.06, and 1.71 and the main results of this paper are robust to using these more conservative critical values.

5. Conclusion

Overall, the findings show that elderly individuals are more likely to use formal home care and less likely to rely on informal home care provided to them by children if they receive an unintended windfall of retirement income stemming from the legislation changes during the 1970s. According to the estimates, an additional $1000 of annual Social Security payment would raise the probability of using formal home care by 2.1 percentage points and reduce the use of informal home care provided by adult children by 2.7 percentage points. Moreover, compared to daughters, informal home care provided by sons is more sensitive to the parent’s retirement income. The findings also show that higher retirement income would encourage elderly individuals who would not have otherwise used home care services to use formal home care and also encourage those who use solely informal home care to use both types of home care services. Finally, I find that the estimated effects of Social Security income are smaller among married and nonwhite elderly individuals and those with less than a high school education.

These findings have important implications for Social Security reform and long-term care policies. The estimated results suggest that Social Security reform aiming at reducing payment to beneficiaries would decrease the use of paid home care and increase retirees’ dependence on unpaid home care provided by adult children. These potential impacts may be favorable among policymakers who aim at curtailing public long-term care expenditures. Reduction in Social Security benefits, however, may reduce the well-being of the elderly in many respects. First, studies have suggested that family caregivers are likely to experience physical or mental problems and face difficulties in balancing work and caregiving (Van Houtven et al., 2013). Although many elderly individuals prefer receiving care in a home setting, the positive gain from family care may be offset by the adverse impacts on caregivers. Second, costs are often the main barrier that prevents the elderly from receiving long-term care. Medicare currently pays for short stays in nursing homes or in-home care under limited conditions and Medicaid only pays for a basic level of care for impoverished seniors. Cutting Social Security benefits would not only discourage elderly individuals with unmet needs to use any type of home care services, it would also reduce the ability of those who have used home care services to pay out-of-pocket. In any event, disabled elderly individuals with unmet long-term care needs are likely to increase as a result of benefit reduction.

Footnotes

The content of this paper does not reflect the official opinion of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the author.

Although these studies use Social Security notch to address the endogeneity of Social Security income, there are differences in how they exploit the notch. Krueger and Pischke (1992) create an aggregate panel data set from the CPS. They construct an earnings history for a hypothetical worker. For each calendar year, age, and birth cohort, they impute the average Social Security benefit according to the time period, the laws that were in effect, and the earnings history for that cohort and then use the imputed benefit variable in the estimation equation. Engelhardt et al. (2005) and Engelhardt (2008) construct an instrumental variable for the mean reported annual Social Security income for each birth cohort/age cell in a method similar to Krueger and Pischke. Snyder and Evans (2006) exploit the exogenous variation in Social Security income by regression discontinuity and difference-in-difference methods (i.e., comparing mortality rates for those born in the first quarter of 1917 with those born in the fourth quarter of 1916). The current paper follows Moran and Simon (2006) and Goda et al. (2011), it uses a binary instrumental variable for cohorts who receive an unexpected windfall of retirement income to address the endogeneity problem of Social Security benefits.

Due to data limitations, Goda et al. (2011) are only able to measure any informal (unpaid) home care use over the 4 weeks prior to the 1993 survey. Using this variable as the dependent variable, their IV estimates suggest that Social Security income increases the use of informal home care. The estimated effect, however, is imprecisely measured.

A number of studies have looked at the relationship between formal and informal home care (Ettner, 1994; Kemper, 1992; Pezzin et al., 1996; Van Houtven and Norton, 2004) and between informal home care and nursing homes (Charles and Sevak, 2005; Van Houtven and Norton, 2004).

The combination of law changes and inflation patterns causes Social Security benefits to decline for retirees born during 1917–1921 (i.e., the notch babies), and the benefits slowly increase for later cohorts.

For a more detailed discussion on the Social Security notch, see Krueger and Pischke (1992) and Snyder and Evans (2006).

Approximately 36% of the sample consists of households with only one member.

One thing worth mentioning here is that, unlike the AHEAD data used in Moran and Simon (2006) and Goda et al. (2011) that only shows a significant first stage relationship for low-educated elderly individuals, the instrument generated from the LSOA II data meets the standard of Staiger and Stock, with first stage F-statistics equal to 24.32. It also passes the Stock and Yogo weak IV test with F-statistics equal to 44.98 (Stock-Yogo critical value assuming a 10% LIML size is 16.38). Moreover, in the LSOA II data, the F-statistics for weak IV test is 18.94 for individuals with lower than a high school education and 22.73 for individuals with a high school education and above. These statistics indicate that the first stage relationship is sufficiently strong for both educational groups and justify the use of a pooled sample to estimate the effect of Social Security income on the outcomes of the elderly.

According to Fig. 1 in Goda et al. (2011), which is created solely based on the Social Security laws, the benefit amount for individuals born in 1911–1917 is significantly above the trend line.

The survey asks respondents whether he/she receives help from other person in any of the ADLs/IADLs activities. If yes, it subsequently asks the activity that they have been helped with, the description/relationship of the helper (e.g., spouse, children, parents, other relatives, friends, and neighbors), and whether the helper was paid.

I also look at other outcome variables, including length of hospital stays, the number of doctor visits, medical devices utilization, Medicaid enrollment, shared-living arrangements, whether the respondent currently works, and whether the respondent has private health insurance. Despite shared-living arrangements, which are significantly and negatively affected by Social Security income, and private health insurance, which is significantly and positively affected by Social Security income, the estimated effects on all other outcomes are small in magnitude and statistically insignificant.

The magnitude of the estimated effect is similar to Goda et al. (2011) that find an income elasticity of approximately 1.6 at the sample means for the low educated.

The results show that Social Security income has a statistically significant negative effect on informal home care provided by children while it is effect on the overall use of informal home care is trivial. In categorizing individuals by the source of informal home care, I could potentially observe the mechanism behind this finding.

2SRI is similar to two-stage least squares (2SLS). 2SLS generates consistent estimators when the second stage equation is linear. 2SRI is requried if the second stage equation is nonlinear. 2SRI and 2SLS will generate the same results if the second stage equation is linear.

For example, the LSOA II baseline data does not include individuals living in institutional settings (e.g., nursing home) while the AHEAD data used in Goda et al. (2011) includes individuals moving from the household population into institutions. Moreover, as described in Engelhardt et al. (2005) and Goda et al. (2011), the 1977 law raised the covered earnings maximum and therefore the fraction of earnings used to calculate Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME) was greater for high-income (high education) workers. The variation was magnified with birth year as younger high-income individuals had a greater proportion of their lifetime earnings exposed to the higher covered earnings maximum. The increase in average annual Social Security income for high-income individuals beginning with cohorts born after 1920 and individuals born in 1930 have almost the same amount of Social Security income as the pre-notch cohorts. The sample in this study includes the 1900–1925 birth cohorts, and therefore the difference in Social Security income between high- and low-income (high and low education) seniors may not be as significant as previous studies.

I choose these restrictions based on Goda et al. (2011) and Moran and Simon (2006).

References

- Beach HM, Boadway RW, Gibbons JO. Social Security and aggregate capital accumulation revisited: dynamic simultaneous estimates in a wealth-generation model. Economic Inquiry. 1984;22:68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AC, Gelbach JG, Miller DL. Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2008;90:414–427. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael F, Charles S. The labour market costs of community care. Journal of Health Economics. 1998;17:645–795. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(97)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichae F, Charles S. The opportunity costs of informal care: does gender matter? Journal of Health Economics. 2003;22:781–803. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles KK, Sevak P. Can family caregiving substitute for nursing home care? Journal of Human Resources. 2005;24:1174–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donald SG, Lang K. Inference with difference in differences and other panel data. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2007;89:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt G, Gruber J, Perry C. Social security and elderly living arrangements: evidence from the social security notch. Journal of Human Resources. 2005;40:354–372. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt G. Social security and elderly homeownership. Journal of Urban Economics. 2008;63:280–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ettner SL. The effect of the Medicaid home care benefit on long-term care choices of the elderly. Economic Inquiry. 1994;32:103–127. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein M, Pellechio A. Social Security and household wealth accumulation: new microeconometric evidence. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1979;61:361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein M. Social Security, induced retirement, and aggregate capital accumulation. Journal of Political Economy. 1974;82:905–926. [Google Scholar]

- Goda GS, Golberstein E, Grabowski DC. Income and the utilization of long-term care services: evidence from the social security benefit notch. Journal of Health Economics. 2011;30:719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper P. The use of formal and informal home care by the disabled elderly. Health Services Research. 1992;27:421–451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger A, Pischke J. The effect of social security on labor supply: a cohort analysis of the notch generation. Journal of Labor Economics. 1992;10:412–437. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry K. Caring for the elderly: the role of adult children. In: Wise D, editor. Economics of Aging. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1999. pp. 133–166. [Google Scholar]

- Moran JR, Simon KI. Income and the use of prescription drugs by the elderly: evidence from the notch cohorts. Journal of Human Resources. 2006;41:411–432. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzin LE, Kemper P, Reschovsky J. Does publicly provided home care substitute for family care? Experimental evidence with endogenous living arrangements. Journal of Human Resources. 1996;31:650–676. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SE, Evans W. The impact of income on mortality: evidence from the social security notch. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2006;88:482–495. [Google Scholar]

- Stock JH, Yogo M. Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In: Stock JH, Andrew DWK, editors. Identification and Inference for Econometric Models: Essays in Honor of Thomas J. Rothenberg. Chapter 5 Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Terza JV, Basu A, Rathouz PJ. Two-stage residual inclusion estimation: addressing endogeneity in health econometric modeling. Journal of Health Economics. 2008;27:531–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven CH, Norton EC. Informal care and health care use of older adults. Journal of Health Economics. 2004;23:1159–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven CH, Coe NB, Skira MM. The effect of informal care on work and wages. Journal of Health Economics. 2013;32:240–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DA, Freedman V, Soldo BJ. The division of family labor: care for elderly parents. Journals of Gerontology. 1997;52B:102–109. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]