Abstract

Background:

Informal caregivers of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis experience increased levels of caregiver burden as the disease progresses. Insight in the factors related to caregiver burden is needed in order to develop supportive interventions.

Aim:

To evaluate the evidence on patient and caregiver factors associated with caregiver burden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis informal caregivers.

Design:

A systematic review.

Data sources:

Four electronic databases were searched up to 2017. Studies that investigated quantitative relations between patient or caregiver factors and caregiver burden were included. The overall quality of evidence for factors was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach.

Results:

A total of 25 articles were included. High quality of evidence was found for the relation between caregiver burden and the factor “behavioral impairments.” Moderate quality of evidence was found for the relations between caregiver burden and the factors “feelings of depression” of the caregiver and “physical functioning” of the patient. The remaining rated caregiver factors—“feelings of anxiety,” “distress,” “social support,” “family functioning,” and “age”—and patient factors—“bulbar function,” “motor function,” “respiratory function,” “disease duration,” “disinhibition,” “executive functioning,” “cognitive functioning,” “feelings of depression,” and “age”—showed low to very low quality of evidence for their association with caregiver burden.

Conclusion:

Higher caregiver burden is associated with greater behavioral and physical impairment of the patient and with more depressive feelings of the caregiver. This knowledge enables the identification of caregivers at risk for caregiver burden and guides the development of interventions to diminish caregiver burden.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, family caregivers, systematic review

What is already known about the topic?

Informal caregivers of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) experience increased caregiver burden during the disease course of the patient.

Little is known regarding which caregiver factors and which patient factors influence caregiver burden in ALS.

What this paper adds?

This systematic review offers a comprehensive overview of both patient and caregiver factors related to caregiver burden in informal caregivers of patients with ALS.

Higher caregiver burden is associated with greater behavioral and physical impairment of the patient and with more depressive feelings of the caregiver.

Implications for practice, theory, or policy

This knowledge enables the identification of caregivers of people with ALS who are at risk for caregiver burden.

This knowledge informs the development of interventions focusing on diminishing burden in caregivers of ALS patients.

More studies are needed that examine caregiver-related factors (such as feelings of competence in caregiving or self-efficacy) in relation to caregiver burden.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease that causes severe restrictions in physical functioning. Patients suffer from progressive weakness of voluntary muscles and approximately 30%–50% of the ALS patients experience cognitive impairments.1,2 The disease leads to an increasing need for care; a major role in this care process is fulfilled by informal caregivers (family, friends, and neighbors).

Caring for an ALS patient is a demanding task. During the course of the disease, the patient may require support with all activities of daily living such as eating, transportation, and medical care.3 Furthermore, caregivers often struggle with accepting this fatal disease, their increased responsibilities, concerns about the future, and feelings of guilt.4 Findings from longitudinal studies indicate that caregivers of patients with ALS experience increasing levels of physical and emotional distress, often referred to as caregiver burden.5,6 Caregiver burden is defined as the impact on the emotional health, physical health, social life, and the financial status of the caregiver as a result of adopting the caregiving role.7

The well-being of caregivers is essential in ALS care; their capacity proves to be an important factor in enabling ALS patients to remain at home until the end of their lives rather than going into a care facility.8 Moreover, studies show a high concordance between the well-being of the patient and that of the caregiver, indicating that a reduced well-being of the caregiver can negatively impact the well-being of the patient.9–11

Knowledge about which factors relate to caregiver burden is needed in order to develop interventions to support caregivers. During the last decade, three reviews have been published concerning the well-being of ALS caregivers, but a comprehensive overview of both modifiable and non-modifiable patient and caregiver factors influencing caregiver burden is lacking.12–14 The objective of this study, therefore, was to systematically review published literature to investigate which caregiver and patient factors are related to caregiver burden in informal caregivers of patients with ALS.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,15 see Supplementary Appendix 1. This systematic review has been registered with PROSPERO 2015 CRD42015019842.

Search strategy

The electronic databases PsycINFO, Medline (PubMed), CINAHL, and EMBASE were systematically searched using the following keywords, along with synonyms: “amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,” “burden,” and “caregiver.” A clinical librarian was consulted regarding the search strategy, which is presented in the online Supplementary Appendix 2. No constraint was placed on the year of publication; searches were conducted up to 2017. Additionally, references were checked for relevant publications. To make sure that no relevant papers had been missed, we sent a list of papers identified through the search to researchers in the field of ALS care for their review.

Inclusion criteria

Studies that investigated quantitative relationships between caregiver or patient factors and caregiver burden in informal ALS caregivers were included. Factors had to be explicitly defined and in case of self-reported constructs measured with a validated questionnaire or a clearly described single question. Burden had to be assessed with a total caregiver burden construct. Only full-text articles, published in peer-reviewed journals, in English, Dutch, or German, were considered eligible.

Exclusion criteria

Mixed sample studies—studies where caregivers of patients with different diagnoses are grouped together—were excluded, unless subsample analysis was performed for ALS caregivers. Studies that described the association solely with subscales of burden measures, or studies that combined burden with other outcomes measures into one overarching outcomes measure, were not taken into account. Intervention studies, qualitative studies, reviews, and case reports were excluded.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts of the articles were independently screened for relevance by two reviewers (J.d.W. and A.C.v.G.); relevant publications, potentially eligible for inclusion, were read in full text by two reviewers (J.d.W. and L.A.B.). Disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. Authors of the studies in the review were contacted by e-mail when information was missing.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias of the included studies was assessed independently by the two researchers who assessed the full-text articles (J.d.W. and L.A.B.). The Methodological Quality Assessment List,16,17 an 8-point checklist that yields a total score between 0 (low methodological quality) and 8 (high methodological quality), was used (Supplementary Appendix 3). Since this checklist was originally applied to research on patients, the relevant characteristics to score item 3 “external validity” were changed into “caregiver age, gender, type of relationship with patient, physical functioning of the patient and time since patient’s diagnosis.” Studies with a total score below 3 were excluded from the quality of evidence assessment. In case of disagreement, a third author was consulted.

Data synthesis

Data were independently extracted from eligible papers by two researchers (J.d.W. and L.A.B.) using structured data forms that were developed for this study and included key components of the study characteristics, study results, and methodological quality of the studies. Due to the diversity of outcome measures and factors included in the study, a meta-analysis was not possible. Bivariate and multivariate associations were described separately in terms of correlation coefficients (r) and standardized β-coefficients (β). In studies that applied a logistic regression, the odds ratio (OR) was presented. Factors were grouped into patient and caregiver characteristics and subsequently thematically categorized.

Quality of evidence

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to assess the overall quality of evidence for each factor measured in at least three studies (Supplementary Appendix 4).18 Two researchers (J.d.W. and L.A.B.) rated the factors on the GRADE criteria study limitations (here we used the Methodological Quality Assessment List), inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The criteria “dose effect” and “moderate/large effect” were omitted, since these criteria were not relevant for the quality of evidence in our review. The overall quality of evidence was classified as high, moderate, low, or very low.

Results

Studies selected

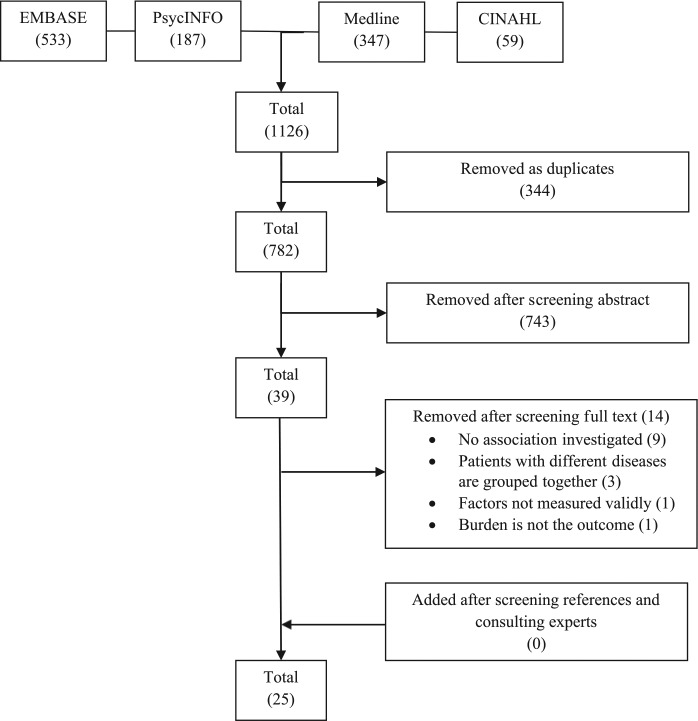

The search identified a total of 1126 possibly relevant articles. After the removal of duplicates and the abstract and full-text screening, a total of 25 studies were left for inclusion in the review (Figure 1). Two study samples were described in two articles each.19–22 Since these articles investigated different factors in relation to burden, they were retained for review.

Figure 1.

Search flowchart.

Risk of bias

The methodological quality scores of the studies ranged from 2 to 7 out of a maximum of 8 (high quality) points (Supplementary Appendix 5). One study scored a low total score, indicating a high risk of bias, and was not incorporated in the quality of evidence assessment.23 The following items of the Methodological Quality Assessment List were not met by the majority of the studies: study participation, proportion sample size versus factors, and confounding bias.

Description of studies included

The key characteristics of each study are presented in Table 1. The included studies were published in eight different countries between 1998 and 2016 and the majority was published in the last decade. A total of 20 studies used a cross-sectional design and 5 studies used a longitudinal design. A total of 22 studies investigated univariate associations; in 10 studies, associations were explored in multivariate models. The study samples ranged from 19 to 415 caregivers. Among the studies that reported the caregiver’s relationship with the patient (n = 22), partners dominated the sample (range, 63%–100%), with two studies recruiting partners only. Other relationships included children, siblings, parents, friends, neighbors, and other relatives. Caregivers were predominantly female and the mean age of caregivers varied from 48 to 61 years. The mean time since disease onset ranged from 15 to 40 months.

Table 1.

The summary of included studies.

| Authors (Year) | Country | Design (follow-up)a | Caregiver sample, n (% female) | Spouse of the patient (%) | Age in years caregivers, mean (SD) | Time since disease onset (o), time since diagnosis (d) Mean (SD) months |

ALSFRS, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrews et al. (2016)24 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 40 (78) | n.r. | 56 (14.5) | 26 (14.2), o | 35.3 (8.9)R |

| Bock et al. (2016)25 | USA | Cross-sectional | 86 (n.r.) | n.r. | n.r. | 26 (48.6), o* | 33.5 (11.1)R* |

| Burke et al. (2015)26 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 33 (66) | 81.3 | 58 (11.1) | 30 (18.2), o | 36.6 (7.8)R |

| Chio et al. (2005)10 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 60 (63) | 76.7 | 58 (12.3) | 28 (25.2), o | 24.6 (10.6) |

| Chio et al. (2010)27 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 70 (67) | 80.0 | 55 (13.3) | 17 (9.3), o | 29.2 (6.1) |

| Creemers et al. (2015)5 | The Netherlands | Longitudinal (12 months) | 126 (66) | 85.0 | 59 (12.5) | 25 (n.r.), o* | 31.8 (8.2)R |

| Galvin et al. (2016)28 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 81 (70) | 71.6 | 55 (13.4) | n.r. | n.r. |

| Gauthier et al. (2007)6 | Italy | Longitudinal (9 months) | 31 (71) | 80.6 | 55 (11.3) | 40 (31.5), o | 28.7 (7.0) |

| Geng et al. (2016)29 | China | Cross-sectional | 81 (68) | 67.9 | 48 (14.5) | 17.8 (14.9), o | 36.5 (8.6) |

| Goldstein et al. (1998)20 | UK | Cross-sectional | 19 (53) | 100 | 60 (12.6) | 34 (23.9), o | n.r. |

| Goldstein et al. (2000)19 | UK | Cross-sectional | 19 (53) | 100 | 60 (12.6) | 34 (23.9), o | n.r. |

| Hecht et al. (2003)30 | Germany | Cross-sectional | 37 (73) | 81.1 | 57 (13.4) | 25 (26.6), d | 23.5 (9.1) |

| Jenkinson et al. (2000)31 | UK | Cross-sectional | 415 (n.r.) | 79.6 | 55 (13.1) | 26 (29.5), o | 25.9 (28.8) |

| Lillo et al. (2012)32 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 140 (69) | 90.0 | 61 (12.0) | 36 (n.r.), o* | 30.4 (9.7)R |

| Pagnini et al. (2010)22 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 40 (70; 78)b | 82.5 | 56 (12.3) | 15 (n.r.), o | 34.9 (7.8)R |

| Pagnini et al. (2011)33 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 37 (62) | 86.5 | 55 (11.4) | 21 (4.2), o | 27.8 (14.7)R |

| Pagnini et al. (2012)21 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 40 (70; 78)b | 82.5 | 56 (12.3) | 15 (n.r.), o | 34.9 (7.8)R |

| Pagnini et al. (2016)34 | Italy | Longitudinal (4 months) | 114 (70) | 82.3 | 57 (13.5) | 32 (50.3), d | 30.6 (9.9) |

| Qutub et al. (2014)23 | USA | Cross-sectional | 50 (66) | n.r. | 61 (n.r.) | 37 (n.r.), o | 34.10 (n.r)R |

| Rabkin et al. (2000)11 | USA | Cross-sectional | 31 (61) | 96.7 | 53 (12.0) | 14 (n.r.), d | 30.4 (4.7) |

| Rabkin et al. (2009)35 | USA | Longitudinal (monthly)c | 71 (74) | 63.0 | 57 (15.0) | n.r. | 23.6 (7.8)R |

| Tramonti et al. (2014)36 | Italy | Longitudinal (6 months) | 19 (68) | 68.4 | 53 (11.6) | <6, d | 18.2 (12.0) |

| Tramonti et al. (2015)37 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 70 (69) | 71.4 | 54 (11.5) | n.r. | n.r. |

| Tremolizzo et al. (2016)38 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 84 (75) | 78.0 | n.r. | 40 (37.5), n.r. | 30.6 (9.0)R |

| Watermeyer et al. (2015)39 | UK | Cross-sectional | 35 (72) | 100 | 58 (10.5) | 30 (14.3), o | 34.1 (8.2)R |

ALSFRS: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functioning Rating Scale [total score range 0–40 (better functioning)]; d: time since diagnosis; n.r.: not reported; o: time since disease onset; R: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functioning Rating Scale Revised [total score range 0–48 (better functioning)]; SD: standard deviation; *: median.

Design of caregiver study.

Not consistently reported.

Only cross-sectional data with regard to burden was analyzed.

Measures of burden

Across studies, five different validated measures of caregiver burden were used (Zarit Burden Interview (n = 11),40 Caregiver Burden Inventory (n = 6),41 Caregiver Strain Index (n = 2),42 Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (n = 1),43 and Caregiver Burden Scale (n = 1))44 and two studies used a number of selected items of the Zarit Burden Interview (see Supplementary Appendix 6). Two studies used a single-item measurement to measure burden.45

Studied factors in relation to caregiver burden in ALS caregivers

Overviews of the studied caregiver and patient factors that were investigated in relation to caregiver burden are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Caregiver factors were grouped into the following categories: emotional functioning, social environment, demographics, personal factors, physical health, and caregiving time. Patient factors were categorized into physical health, behavioral impairments, cognitive impairments, emotional functioning, personal factors, demographics, and social environment.

Table 2.

Associations between caregiver factors and caregiver burden.

| Factora | Measure factor | Outcome caregiver burden | Bivariate association |

Bivariate analysis | Multivariate association |

N | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | β/OR (CI) | |||||||

| Emotional functioning | Feelings of depression | BDI | ZBI-6 items | 0.49* | P | – | 31 | 11 |

| BDI | CBI | 0.51*** | P | – | 82 | 38 | ||

| BDI-II | ZBI | 0.43** | P | – | 40 | 21 | ||

| BDI-II | ZBI | +n.r.*** | R | – | 50 | 23 | ||

| ZDS | CBI | 0.55*** | S | +n.r.*** (n.r.) | 60 | 10 | ||

| ZDS | CBI | – | – | n.r.* (n.r.) | 70 | 27 | ||

| ZDS | CBI | n.r.* | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | ||

| ZDS (t1) | CBI (t1) | n.r.* | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | ||

| HADS-Depression (t0–t3) | CSI (t0–t3) | – | – | ns | 116 | 5 | ||

| HADS-Depression | ZBI | 0.57*** | P | ns | 35 | 39 | ||

| DASS-Depression | ZBI-sv | – | – | nsor | 140 | 32 | ||

| Depression-Somatic | BDI-II-Somatic | ZBI | 0.84*** | S | – | 40 | 22 | |

| Depression-Psychological | BDI-II-Psychological | ZBI | 0.57* | S | – | 40 | 22 | |

| Feelings of anxiety | HADS-Anxiety | ZBI | 0.37* | P | ns | 35 | 39 | |

| HADS-Anxiety (t0–t3) | CSI (t0–t3) | – | – | 0.19*** (0.086, 0.286) | 116 | 5 | ||

| DASS-Anxiety | ZBI-sv | – | nsor | 140 | 32 | |||

| STAI-Trait | ZBI | 0.36* | P | – | 40 | 21 | ||

| STAI-Trait | ZBI-6 items | 0.40n.r. | P | – | 31 | 11 | ||

| Distress | HADS-Total | ZBI | 0.62*** | R | – | 33 | 26 | |

| HADS-Total | ZBI | – | – | +n.r.** (n.r.) | 81 | 28 | ||

| DASS-Stress | ZBI-sv | – | – | 1.12or* (0.86, 1.00) | 140 | 32 | ||

| Mental health | SF-36-MCS | CSI | 0.50*** | n.r. | – | 415 | 31 | |

| Hopelessness | BHS | ZBI-6 items | ns | P | – | 31 | 11 | |

| Social environment | Social support | MQoL-Ss | ZBI | −0.73*** | S | – | 40 | 22 |

| 5-point scale | ZBI | ns | P | – | 31 | 11 | ||

| No. of friends/relatives seen | Strain Index | ns | S | – | 19 | 19 | ||

| No. of close friends | Strain Index | ns | S | – | 19 | 19 | ||

| No. of friends that can help | Strain Index | ns | S | – | 19 | 19 | ||

| No. of substitute cgs | CBI | ns | S | – | 60 | 10 | ||

| Participating in support group | BSFC | ns | S | – | 37 | 30 | ||

| Participating in support group | CBI | ns | S | – | 60 | 10 | ||

| Outside help received | ZBI | ns | R | – | 50 | 23 | ||

| Hours per week help | ZBI | ns | R | – | 50 | 23 | ||

| Family functioning | FACES-Real cohesion | CBI | ns | S | – | 19 | 36 | |

| FACES-Real cohesion (t0) | CBI (t1) | – | – | 0.53* (n.r.) | 19 | 36 | ||

| FACES-Ideal cohesion | CBI | ns | S | – | 19 | 36 | ||

| FACES-Real adaptability | CBI | ns | S | – | 19 | 36 | ||

| FACES-Ideal adaptability | CBI | ns | S | – | 19 | 36 | ||

| MIS | ZBI | −0.45** | P | ns | 35 | 39 | ||

| MIS (change) | ISS-1 | 0.50* | n.r. | – | 19 | 20 | ||

| Quality of care cgs | Numerical scale (t0–t3) | CSI (t0–t3) | – | – | −0.45*** (−0.672, −0.232) | 116 | 5 | |

| Demographics | Age | Years | CBI | ns | S | – | 60 | 10 |

| Years | CBI | ns | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | ||

| Years | CBI | 0.24* | S | – | 70 | 37 | ||

| Years | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | ||

| Years | ZBI | – | – | ns | 81 | 28 | ||

| Years | ZBI | −n.r.** | R | – | 50 | 23 | ||

| Years | ZBI | – | – | 0.19* (n.r.) | 81 | 29 | ||

| Gender | Male/female | CBI | ns | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | |

| Male/female | ZBI | – | – | ns | 81 | 28 | ||

| Years married | Years | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | |

| Relationship patient | Spouse/child/parent/.. | ZBI | – | – | ns | 81 | 28 | |

| Living with patient | Yes/no | ZBI | – | – | ns | 81 | 28 | |

| Household income | Dollars | ZBI | ns | R | – | 50 | 23 | |

| Personal factors | State of mindfulness | LMS | ZBI | −0.27** | P | – | 140 | 34 |

| LMS (t1) | ZBI (t1) | −0.29* | P | – | 140 | 34 | ||

| LMS (t0 + t1) | ZBI (t0 + t1) | – | – | −n.r.* (n.r.) | 140 | 34 | ||

| Religiosity | RBI | ZBI-6 items | ns | P | – | 31 | 11 | |

| Not-very religious | ZBI | ns | R | – | 50 | 23 | ||

| Positive meaning in caring | FM-4 items | ZBI-6 items | 0.49** | P | – | 31 | 11 | |

| Passive coping | UCL-PA (t0–t3) | CSI (t0–t3) | – | 0.15* (0.015, 0.289) | 116 | 5 | ||

| Illness affects life areas | ISS-4 | ISS-1 | 0.50* | n.r. | – | 19 | 20 | |

| Attribution style | Globality attribution measure | Strain Index | 0.58** | S | – | 19 | 19 | |

| Control over reactions | Control over reactions measure | Strain Index | −n.r.* | S | – | 19 | 19 | |

| Physical health | Physical functioning | SF-36-PCS | CSI | 0.28*** | n.r. | – | 415 | 31 |

| Physical fatigue | CFS-physical fatigue | ZBI-6 items | 0.36n.r. | P | – | 31 | 11 | |

| Caregiving time | Time caring | Hours per day | ZBI | ns | R | – | 33 | 26 |

| Hours per week | ZBI | – | n.r.* (n.r.) | 81 | 28 | |||

| Hours per day | ZBI | +n.r.* | R | – | 50 | 23 | ||

| Time with patient | Hours per day | ZBI | ns | – | 50 | 23 | ||

| % time caring | % time of day | ZBI | ns | – | 50 | 23 |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale; BSFC: Burden Scale for Family Caregivers; CBI: Caregiver Burden Inventory; CFS-physical fatigue: Chalder Fatigue Scale, Physical Fatigue subscale; cgs: caregivers; CI: confidence interval; CSI: Caregiver Strain Index; DASS: Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale; FACES: Family Adaptation and Cohesion Evaluation Scale; FM: Folkman’s 4-item measure of finding positive meaning in caregiving; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; ISS: Item Strain Scale; LMS: Langer Mindfulness Scale; MIS: Marital Intimacy Scale; MQoL-Ss: McGill Quality of Life social support subscale; n.r.: not reported; no.: number; ns: not significant; or: odds ratio; P: Pearson’s product moment correlation; R: univariate regression analysis; RBI: Religious Beliefs Inventory; S: Spearman’s rank order correlation; SF-36: 36-item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire; SF-36-MCS: 36-item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire Mental Component; SF-36-PCS: 36-item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire Physical Component; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; UCL-PA: Utrecht Coping List Passive Approach subscale; ZBI: Zarit Burden Interview; ZBI-sv: Zarit Burden Interview-short version; ZDS: Zung Depression Scale.

Factors and outcomes are measured at t0 unless mentioned otherwise.

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Table 3.

Associations between patient factors and caregiver burden.

| Factora | Measure factor | Outcome caregiver burden | Bivariate association |

Bivariate analysis | Multivariate association |

N | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | β/OR (CI) | |||||||

| Physical health | Physical functioning | ALSFRS | CBI | −0.61*** | S | −n.r.*** (n.r.) | 60 | 10 |

| ALSFRS | CBI | −0.61*** | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | ||

| ALSFRS (t1) | CBI (t1) | −0.64*** | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | ||

| ALSFRS | CBI | −0.44** | S | – | 70 | 37 | ||

| ALSFRS-R | CBI | −0.52*** | P | – | 84 | 38 | ||

| ALSFRS | BSFC | −0.47** | S | – | 37 | 30 | ||

| ALSFRS-R | ZBI | −0.46* | S | – | 40 | 22 | ||

| ALSFRS-R | ZBI | ns | R | – | 33 | 26 | ||

| ALSFRS-R | ZBI | ns | S | – | 40 | 24 | ||

| ALSFRS-R | ZBI | ns | R | – | 50 | 23 | ||

| ALSFRS-R | ZBI-5 items | ns | P | – | 71 | 35 | ||

| ALSFRS-R | CGBS | – | – | −0.58* (−1.1, −0.01) | 86 | 25 | ||

| ALSFRS-R (t0–t3) | CSI (t0–t3) | – | – | −0.13*** (−0.170, −0.092) | 116 | 5 | ||

| Bulbar function | ALSFRS-Bulbar | CBI | ns | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | |

| ALSFRS-Bulbar | ZBI-sv | – | – | nsor | 140 | 32 | ||

| ALSFRS-R-Bulbar | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | ||

| Motor function | ALSFRS-R-Limb | ZBI | −0.66*** | P | −0.51** (n.r.) | 35 | 39 | |

| ALSFRS-R-Upper limb | CBI | n.r.* | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | ||

| ALSFRS-Lower limb | CBI | n.r.* | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | ||

| ALSFRS-Fine motor | ZBI-sv | – | – | nsor | 140 | 32 | ||

| ALSFRS-Gross motor | ZBI-sv | – | – | nsor | 140 | 32 | ||

| ALSFRS-R Fine & Gross | ZBI | – | – | −0.52*** (n.r.) | 81 | 29 | ||

| Respiratory function | ALSFRS-Respiration | CBI | ns | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | |

| ALSFRS-Respiration | ZBI-sv | – | – | nsor | 140 | 32 | ||

| ALSFRS-R-Respiration | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | ||

| FVC | ZBI | −0.42** | P | – | 40 | 21 | ||

| PCF | ZBI | −0.35* | P | – | 40 | 21 | ||

| Disease progression | Progression indexb | CBI | 0.27* | P | – | 84 | 38 | |

| Physical health | SF-36-PCS | CSI | 0.51*** | n.r. | – | 415 | 31 | |

| Self care | CBI-R-Self care | ZBI | ns | S | – | 40 | 24 | |

| Everyday skills | CBI-R-Everyday skills | ZBI | 0.41** | S | – | 40 | 24 | |

| Disease duration | Years | CBI | – | – | n.r.* (n.r.) | 60 | 10 | |

| Months | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | ||

| Months | CBI | ns | P | – | 84 | 38 | ||

| Behavioral impairments | Behavioral impairments | FrSBe-Total | CBI | 0.38*** | P | +n.r.* (n.r.) | 70 | 27 |

| FrSBe-Total | ZBI | 0.69*** | P | 0.69** (n.r.) | 35 | 39 | ||

| CBI-R-Total | ZBI | 0.66*** | S | – | 40 | 24 | ||

| FrSBe-Total (change) | ZBI | 0.56* | R | – | 33 | 26 | ||

| ALS-CBS-Behavior | CGBS | −0.76*** | R | −0.69*** (−0.98, −0.41) | 86 | 25 | ||

| ALS-CBS-Behavior | CBI | −0.22* | P | −n.r.* (n.r.) | 84 | 38 | ||

| Apathy | FrSBe-Apathy | ZBI | 0.63*** | P | ns | 35 | 39 | |

| FrSBe-Apathy (change) | ZBI | 0.39* | R | – | 33 | 26 | ||

| Disinhibition | FrSBe-Disinhibition | CBI | ns | P | – | 70 | 27 | |

| FrSBe-Disinhibition | ZBI | 0.51** | P | ns | 35 | 39 | ||

| FrSBe-Disinhibition (change) | ZBI | 0.53** | R | – | 33 | 26 | ||

| Executive functioning | FrSBe-Executive dysfunction | CBI | 0.44*** | P | ns | 70 | 27 | |

| FrSBe-Executive dysfunction | ZBI | 0.51** | P | ns | 35 | 39 | ||

| FrSBe-Executive dysfunction (change) | ZBI | 0.37* | R | – | 33 | 26 | ||

| Battery of tests | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | ||

| Behavior abnormalities | CBI-R-Abnormal behavior | ZBI-sv | – | – | 1.44or** (1.13, 1.85) | 140 | 32 | |

| CBI-R-Abnormal behavior | ZBI | 0.38* | S | – | 40 | 24 | ||

| Eating habits | CBI-R-Eating habits | ZBI-sv | – | – | nsor | 140 | 32 | |

| CBI-R-Eating habits | ZBI | 0.36* | S | – | 40 | 24 | ||

| Stereotypic and motor behaviors | CBI-R-Stereotypical motor behavior | ZBI-sv | – | – | nsor | 140 | 32 | |

| CBI-R-Stereotypical motor behavior | ZBI | 0.32* | S | – | 40 | 24 | ||

| Motivation | CBI-R-Lack of motivation | ZBI-sv | – | – | nsor | 140 | 32 | |

| CBI-R-Lack of motivation | ZBI | 0.43** | S | – | 40 | 24 | ||

| Odd beliefs | CBI-R-Odd beliefs | ZBI | ns | S | – | 40 | 24 | |

| Cognitive impairments | Overall cognitive functioning | Neuropsychological tests | ZBI | ns | R | – | 33 | 26 |

| MMSE | CBI | ns | P | – | 84 | 38 | ||

| FAB | CBI | ns | P | – | 84 | 38 | ||

| ALS-CBS-Cognition | CBI | ns | P | – | 84 | 38 | ||

| ALS-CBS-Cognition | CGBS | −1.4* | R | −1.42* (−2.8, −0.05) | 86 | 25 | ||

| Attention | ALS-CBS-Attention | CGBS | −0.25* | R | – | 86 | 25 | |

| Concentration | ALS-CBS-Concentration | CGBS | −0.25* | R | – | 86 | 25 | |

| Fluency | ALS-CBS-Fluency | CGBS | ns | R | – | 86 | 25 | |

| Memory/orientation | CBI-R Memory/orientation | ZBI | 0.63*** | S | – | 40 | 24 | |

| Executive functioning | WST | CBI | ns | P | – | 84 | 38 | |

| Social cognition | Battery of tests | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | |

| Emotional functioning | Feelings of depression | HADS-Depression (t0–t3) | CSI (t0–t3) | – | – | ns | 116 | 5 |

| HADS-R-Depression | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | ||

| BDI | CBI | ns | P | – | 79 | 38 | ||

| Anxiety | HADS-R-Anxiety | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | |

| Emotional functioning | ALSAQ-40Se (t0–t3) | CSI (t0–t3) | – | – | 0.02* (0.022, 0.042) | 116 | 5 | |

| Lability | ELQ | ZBI | ns | P | – | 35 | 39 | |

| Mental health | SF-36-MCS | CSI | 0.28*** | n.r. | – | 415 | 31 | |

| Mood | CBI-R-Mood | ZBI | 0.38* | S | – | 40 | 24 | |

| Personal factors | Existential well-being | MQol-Ewbs | ZBI | −0.60*** | P | – | 37 | 33 |

| Religion is source of strength | ALSSQoL-R statement (0–10) | ZBI | −0.43*** | P | – | 37 | 33 | |

| Consider self as religious/spiritual | ALSSQoL-R statement (0–10) | ZBI | −0.49*** | P | – | 37 | 33 | |

| Self perceived as burden | SPBS | CBI | 0.33* | S | ns | 60 | 10 | |

| SPBS | CBI | 0.41* | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | ||

| SPBS (t1) | CBI (t1) | 0.38* | n.r. | – | 31 | 6 | ||

| Burden cg rated by patient | Visual analogue scale | ZBI-5 items | 0.29* | P | – | 71 | 35 | |

| Active coping | UCL-AA (t0–t3) | CSI (t0–t3) | – | – | ns | 116 | 5 | |

| Demographics | Age | Years | ZBI | ns | R | – | 33 | 26 |

| Years | ZBI | 0.35* | P | ns | 35 | 39 | ||

| Years | CSI (t0–t3) | – | – | ns | 116 | 5 | ||

| Gender | Male/female | ZBI | ns | R | – | 33 | 26 | |

| Male/female | CGBS | – | – | 8.1* (1.0, 15.2) | 86 | 25 | ||

| Social environment | Social support | MQoL-Ss | ZBI | −0.53** | P | – | 40 | 21 |

| Quality of care | n.r. (t0–t3) | CSI (t0–t3) | – | – | ns | 116 | 5 | |

| Family functioning | FACES-Ideal cohesion | CBI | −0.59** | S | – | 19 | 36 | |

| Reimbursement costs care | Yes/no | ZBI | – | – | −0.19* (n.r.) | 81 | 29 |

ALSAQ-40Se: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Assessment Questionnaire 40-item subscale emotional functioning; ALS-CBS: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Cognitive-Behavioral Screen; ALSFRS: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale; ALSFRS-R: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale-Revised; ALSSQoL-R: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Specific Quality of Life-Revised questionnaire; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BSFC: Burden Scale for Family Caregivers; CBI: Caregiver Burden Inventory; CBI-R: Cambridge Behavioural Inventory Revised; CGBS: Caregiver Burden Scale; CI: confidence interval; CSI: Caregiver Strain Index; ELQ: Emotional Lability Questionnaire; FAB: Frontal Assessment Battery; FACES: Family Adaptation and Cohesion Evaluation Scale; FrSBe: Frontal Systems Behavior Scale; FVC: Forced Vital Capacity; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HADS-R: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Revised; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MQoL-Ewbs: McGill Quality of Life existential well-being subscale; MQoL-Ss: McGill Quality of Life social support subscale; n.r.: not reported; ns: not significant; or: odds ratio; P: Pearson’s product moment correlation; PCF: Peak Cough Flow; R: univariate regression analysis; S: Spearman’s rank order correlation; SF-36-MCS: 36-item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire Mental Component; SF-36-PCS: 36-item Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire Physical Component; SPBS: Self-Perceived Burden Scale; UCL-AA: Utrecht Coping List Active Approach subscale; WST: Weigl’s Sorting test; ZBI: Zarit Burden Interview; ZBI-sv: Zarit Burden Interview-short version.

Factors and outcomes are measured at t0 unless mentioned otherwise.

Calculated as ([48-ALSFRS-R]/disease duration in months).

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Evidence for factors related to caregiver burden

Caregiver factors

The synthesis of evidence for the caregiver factors using the GRADE criteria resulted in a rating of moderate quality of evidence for the relationship between higher caregiver burden and “feelings of depression” (see Table 4). Low quality of evidence was found for the relations between higher caregiver burden and the factors “anxiety,” “distress,” and “age.” The social environment factors “social support” and “family functioning” showed very low quality of evidence as factors associated with lower caregiver burden.

Table 4.

Adapted GRADE table for narrative systematic reviews of prognostic studies.

| Potential factors | Participants (n) | No. of studies | Bivariatea |

Multivariate |

Grade factors |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | 0 | − | n.r. | + | 0 | − | n.r. | Study limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Overall quality | |||

| Caregiver | ||||||||||||||||

| Feelings of depression | 605 | 9 | 5 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 3 | – | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Moderate |

| Feelings of anxiety | 362 | 5 | 2 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 2 | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Low |

| Distress | 254 | 3 | 1 | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Low |

| Social support | 187 | 5 | – | 7 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Very low |

| Family functioning | 73 | 3 | – | 4 | 2 | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Very low |

| Age | 474 | 7 | 1 | 3 | – | – | 1 | 2 | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Low |

| Patient | ||||||||||||||||

| Physical functioning | 668 | 11 | – | 3 | 6 | – | – | – | 3 | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Moderate |

| Bulbar function | 206 | 3 | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Low |

| Motor function | 287 | 4 | – | – | 1 | 2 | – | 2 | 2 | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Very low |

| Respiratory function | 246 | 4 | – | 2 | 2 | – | – | 1 | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Very low |

| Disease duration | 179 | 3 | – | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Very low |

| Behavioral impairments | 348 | 6 | 6 | – | – | – | 4 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | High |

| Disinhibition | 138 | 3 | 2 | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Very low |

| Executive functioning | 138 | 3 | 3 | 1 | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Very low |

| Cognitive functioning | 203 | 3 | 1 | 4 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Very low |

| Feelings of depression | 230 | 3 | – | 2 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Low |

| Age | 184 | 3 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | 2 | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | Very low |

For uni- and multivariate analyses: +: number of significant associations with a positive value; 0: number of non-significant associations; −: number of significant associations with a negative value; n.r.: number of associations of which the direction was not reported. For GRADE factors: ✓: no serious limitations; ✕: serious limitations. For overall quality of evidence: very low, low, moderate, high.

Bivariate associations that are measured twice in one study on different measuring points are counted as one association.

Factors within the categories personal factors, physical health of the caregiver, and caregiving time were investigated in fewer than three studies and could not, therefore, be rated with the GRADE.

Patient factors

The synthesis of the evidence for the patient factors led to a rating of high quality evidence for the relationship between higher caregiver burden and “behavioral impairments.” This factor represents total scores of questionnaires that measure behavioral impairments in patients, which was investigated in six studies. Patients’ “physical functioning” was most frequently studied (n = 11). There was moderate quality of evidence for the relation between decreased physical functioning and higher caregiver burden. Very low quality of evidence was found for the association with higher caregiver burden and the factors “limb function,” “respiratory function,” “executive functioning,” “cognitive functioning,” and “age.” Low evidence was found for “bulbar function” and “feelings of depression,” and very low quality of evidence for “disease durations” as factors not associated with caregiver burden.

Since each of the factors within the categories personal factors and social environment was studied in one or two studies, no synthesis of evidence could be performed.

Discussion

In our systematic review, we focused on both patient factors and caregiver factors in relation to burden in caregivers of ALS patients. Moderate to high quality of evidence was found for “behavioral impairments” of the patient, “physical functioning” of the patient, and “feelings of depression” of the caregiver as factors related to caregiver burden. These results indicate that there is a specific group of caregivers that is vulnerable to caregiver burden. For the relations between caregiver burden and the remaining caregiver and patient factors, the quality of evidence was low to very low and no general conclusions could be drawn.

We found high quality of evidence for the relation between caregiver burden and behavioral impairments of the patient. Behavioral impairments such as apathy or disinhibition occur in a substantial proportion of ALS patients and 5%–15% of patients meet the criteria for frontotemporal dementia (FTD), which is associated with more severe behavioral impairments.46,47 The findings of this review highlight the impact of behavioral impairments in patients on caregiver burden, whereas cognitive impairments in patients are less likely to result in caregiver burden. This underscores the relevance of the distinction between pure ALS, ALS with behavioral impairment, ALS with cognitive impairment, and ALS with FTD.48

Moderate quality of evidence was found for the relation between caregiver burden and the level of physical functioning of the patient. Caregiver burden seems to increase parallel to the disease severity of the patient, which is in line with conclusions in other progressive neurological diseases.49,50 Low to very low quality of evidence was found for the relation between caregiver burden and factors measuring functioning in specific physical areas (e.g. respiratory function, motor function), indicating that burden seems to be related to the overall physical functioning but not to specific functions. The increase in burden may be the result of the fact that ALS leads to rapid decline in physical functioning, as this constantly requires physical and emotional adjustments from both patient and caregiver.51,52 Furthermore, as the disease progresses, worsening of symptoms and physical concerns may lead to increased stress, worries, and burden of caregivers, taking a toll on their time and energy for leisure activities and time to fulfill their own needs.10,22

Moderate quality of evidence was found for the relation between caregiver burden and feelings of depression of the caregiver; in other words, caregivers, who experience depressive symptoms, are more likely to experience high caregiver burden. This association between caregiver burden and depressive symptoms experienced by the caregiver is consistent with findings in other neurological diseases, such as dementia and stroke.50,53 Caregivers who experience feelings of depression may find it even more challenging to cope with the caregiving demands placed on them, which influences caregiver burden. Although research seems to indicate that caregiver burden and depression are distinct constructs,54,55 there might be conceptual overlap between the measures of depressive symptoms and caregiver burden.56 Questions related to depressive feelings are often included in burden measures (e.g. I feel emotionally drained due to caring for him or her. Caregiver Burden Inventory item 9; Do you feel tired and worn out? Caregiver Burden Scale item 1). However, in this review, we conceived caregiver burden and depression as two separate concepts because caregiver burden represents outcomes specific to the caregiving situation, while measurements of depression represent a more general outcome.

In previous systematic reviews, the suggestion was made that social support might be a protective factor for caregiver burden,12,57 but this result could not be confirmed in our review. This difference might be attributed to the inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative studies. An alternative explanation could be that only specific subtypes of social support (i.e. emotional, instrumental, informational, or appraisal support)58 mitigate caregiver burden. For example, the benefits of receiving social support in caregiving (instrumental support) may be overestimated in ALS care, as taking over caregiving tasks is complicated, especially in later stages of the disease. Family members and friends are often not equipped to offer this specialized care to the patient.4 Hence, relieving the burden of the caregiver by providing physical support in caregiving seems to be a difficult task for their social environment, while relieving caregiver burden with emotional support may be more feasible. However, it was impossible to make this differentiation in our review due to scarcity of research in this topic.

This systematic review offers insight into factors related to caregiver burden and guides the development of interventions aiming to reduce caregiver burden, but more additional research into factors related to caregiver burden is needed. Personal factors of ALS caregivers are possible modifiable factors but are currently understudied. Only 6 out of 25 of the studies included in this review paid attention to these factors. More knowledge about personal caregiver factors, such as feelings of competence in caregiving or self-efficacy, is needed since these personal factors seem to play a protective role in the development of burden in caregivers of patients with dementia.59

Strengths and limitations

This review was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines; the quality of the evidence was judged by assessing the risk of bias, and the GRADE approach was used, which are strengths of this review.

There were also some limitations of the review. First, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis because of the heterogeneity of both the measures used to assess caregiver burden and the measures used to assess the associated factors.

Second, the instruments used to assess caregiver burden represented different interpretations of the concept, caregiver burden. Therefore, we only included studies which assessed a total score on burden as this represents a general concept of burden. Others have suggested, however, that the use of multidimensional measures of caregiver burden might provide different information.60 For the interpretation of results on caregiver burden, and the comparison of intervention effects, a gold standard for the measurement of burden in ALS caregivers would be preferable.

Third, we only included full-text, peer-reviewed published studies and therefore might have missed evidence about relationships between patient and caregiver factors and caregiver burden.

Finally, the overwhelming majority of studies was cross-sectional and does not, therefore, allow any causal inferences between caregiver burden and factors. Longitudinal data are required to understand the temporal pattern of caregiver burden, its determinants, and the optimal time to deliver an intervention to diminish caregiver burden.

Conclusion

This review presents the current knowledge on associations between both patient factors and caregiver factors which are related to caregiver burden in ALS caregivers. There is moderate to high quality of evidence for the relation between behavioral impairments of the patient and caregiver burden, physical functioning of the patient and caregiver burden, and feelings of depression of the caregiver himself or herself and caregiver burden. This is important knowledge in order to identify those caregivers who are at risk of caregiver burden and to inform the development of interventions focusing on diminishing burden in caregivers of ALS patients.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors are grateful to the Netherlands ALS Foundation for funding this study.

References

- 1. Phukan J, Elamin M, Bede P, et al. The syndrome of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012; 83: 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zarei S, Carr K, Reiley L, et al. A comprehensive review of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Surg Neurol Int 2015; 6: 171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chio A, Gauthier A, Vignola A, et al. Caregiver time use in ALS. Neurology 2006; 67: 902–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weisser FB, Bristowe K, Jackson D. Experiences of burden, needs, rewards and resilience in family caregivers of people living with Motor Neurone Disease/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: a secondary thematic analysis of qualitative interviews. Palliat Med 2015; 29: 737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Creemers H, de Moree S, Veldink JH, et al. Factors related to caregiver strain in ALS: a longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016; 87: 775–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gauthier A, Vignola A, Calvo A, et al. A longitudinal study on quality of life and depression in ALS patient-caregiver couples. Neurology 2007; 68: 923–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zarit SH, Todd PA, Zarit JM. Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. Gerontologist 1986; 26: 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goutman SA, Nowacek DG, Burke JF, et al. Minorities, men, and unmarried amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients are more likely to die in an acute care facility. Amyotroph Later Scler Frontotemp Degener 2014; 15: 440–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boerner K, Mock SE. Impact of patient suffering on caregiver well-being: the case of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and their caregivers. Psychol Health Med 2012; 17: 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chio A, Gauthier A, Calvo A, et al. Caregiver burden and patients’ perception of being a burden in ALS. Neurology 2005; 64: 1780–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rabkin JG, Wagner GJ, Del Bene M. Resilience and distress among amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and caregivers. Psychosom Med 2000; 62: 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aoun SM, Bentley B, Funk L, et al. A 10-year literature review of family caregiving for motor neurone disease: moving from caregiver burden studies to palliative care interventions. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pinho AC, Goncalves E. Are amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caregivers at higher risk for health problems? Acta Med Port 2016; 29: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bergin S, Mockford C. Recommendations to support informal carers of people living with motor neurone disease. Br J Commun Nurs 2016; 21: 518–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Van Leeuwen CM, Kraaijeveld S, Lindeman E, et al. Associations between psychological factors and quality of life ratings in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 174–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Groenestijn AC, Kruitwagen-van Reenen ET, Visser-Meily JMA, et al. Associations between psychological factors and health-related quality of life and global quality of life in patients with ALS: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Out 2016; 14: 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huguet A, Hayden JA, Stinson J, et al. Judging the quality of evidence in reviews of prognostic factor research: adapting the GRADE framework. Syst Rev 2013; 2: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goldstein LH, Adamson M, Barby T, et al. Attributions, strain and depression in carers of partners with MND: a preliminary investigation. J Neurol Sci 2000; 180: 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goldstein LH, Adamson M, Jeffrey L, et al. The psychological impact of MND on patients and carers. J Neurol Sci 1998; 160(Suppl. 1): S114–S121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pagnini F, Banfi P, Lunetta C, et al. Respiratory function of people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and caregiver distress level: a correlational study. Biopsychsoc Med 2012; 6: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pagnini F, Rossi G, Lunetta C, et al. Burden, depression, and anxiety in caregivers of people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Psychol Health Med 2010; 15: 685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Qutub K, Lacomis D, Albert SM, et al. Life factors affecting depression and burden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caregivers. Amyotroph Later Scler Frontotemp Degener 2014; 15: 292–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Andrews SC, Pavlis A, Staios M, et al. Which behaviours? Identifying the most common and burdensome behaviour changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Psychol Health Med 2017; 22: 483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bock M, Duong YN, Kim A, et al. Cognitive-behavioral changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: screening prevalence and impact on patients and caregivers. Amyotroph Later Scler Frontotemp Degener 2016; 17: 366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burke T, Elamin M, Galvin M, et al. Caregiver burden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a cross-sectional investigation of predictors. J Neurol 2015; 262: 1526–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chio A, Vignola A, Mastro E, et al. Neurobehavioral symptoms in ALS are negatively related to caregivers’ burden and quality of life. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17: 1298–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Galvin M, Corr B, Madden C, et al. Caregiving in ALS—a mixed methods approach to the study of Burden. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Geng D, Ou R, Miao X, et al. Patients’ self-perceived burden, caregivers’ burden, and quality of life for ALS patients: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. Epub ahead of print 26 April 2017. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.13667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hecht MJ, Gräsel E, Tigges S, et al. Burden of care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Palliat Med 2003; 17: 327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Swash M, et al. The ALS Health Profile Study: quality of life of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and carers in Europe. J Neurol 2000; 247: 835–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lillo P, Mioshi E, Hodges JR. Caregiver burden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is more dependent on patients’ behavioral changes than physical disability: a comparative study. BMC Neurol 2012; 12: 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pagnini F, Lunetta C, Rossi G, et al. Existential well-being and spirituality of individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is related to psychological well-being of their caregivers. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2011; 12: 105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pagnini F, Phillips D, Bosma CM, et al. Mindfulness as a protective factor for the burden of caregivers of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. J Clin Psychol 2016; 72: 101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rabkin JG, Albert SM, Rowland LP, et al. How common is depression among ALS caregivers? A longitudinal study. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009; 10: 448–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tramonti F, Barsanti I, Bongioanni P, et al. A permanent emergency: a longitudinal study on families coping with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Fam Syst Health 2014; 32: 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tramonti F, Bongioanni P, Leotta R, et al. Age, gender, kinship and caregiver burden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Psychol Health Med 2015; 20: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tremolizzo L, Pellegrini A, Susani E, et al. Behavioural but not cognitive impairment is a determinant of caregiver burden in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur Neurol 2016; 75: 191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Watermeyer TJ, Brown RG, Sidle KCL, et al. Impact of disease, cognitive and behavioural factors on caregiver outcome in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Later Scler Frontotemp Degener 2015; 16: 316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980; 20: 649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Novak M, Guest C. Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist 1989; 29: 798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Robinson BC. Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. Journal of Gerontology 1983; 38: 344–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gräsel E. Somatic symptoms and caregiving strain among family caregivers of older patients with progressive nursing needs. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 1995; 21: 253–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Elmstahl S, Malmberg B, Annerstedt L. Caregiver’s burden of patients 3 years after stroke assessed by a novel caregiver burden scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77: 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morris LW, Morris RG, Britton PG. The relationship between marital intimacy, perceived strain and depression in spouse caregivers of dementia sufferers. Br J Med Psychol 1988; 61: 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lillo P, Mioshi E, Zoing MC, et al. How common are behavioural changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2011; 12: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Phukan J, Pender NP, Hardiman O. Cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 994–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Strong MJ, Grace GM, Freedman M, et al. Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of frontotemporal cognitive and behavioural syndromes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2009; 10: 131–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Leiknes I, Lien U, Severinsson E. The relationship among caregiver burden, demographic variables, and the clinical characteristics of patients with Parkinson’s disease—a systematic review of studies using various caregiver burden instruments. Open J Nurs 2015; 5: 855–877. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chiao CY, Wu HS, Hsiao CY. Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev 2015; 62: 340–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Williams MT, Donnelly JP, Holmlund T, et al. Family caregiver needs and quality of life. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2008; 9: 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. King SJ, Duke MM, O’Connor BA. Living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neurone disease (ALS/MND): decision-making about “ongoing change and adaptation.” J Clin Nurs 2009; 18: 745–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rigby H, Gubitz G, Phillips S. A systematic review of caregiver burden following stroke. Int J Stroke 2009; 4: 285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Given B, Wyatt G, Given C, et al. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004; 31: 1105–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gitlin LN, Belle SH, Burgio LD, et al. Effect of multicomponent interventions on caregiver burden and depression: the REACH multisite initiative at 6-month follow-up. Psychol Aging 2003; 18: 361–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Clyburn LD, Stones MJ, Hadjistavropoulos T, et al. Predicting caregiver burden and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2000; 55: S2–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mockford C, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R. A review: carers, MND and service provision. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2006; 7: 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Langford CP, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, et al. Social support: a conceptual analysis. J Adv Nurs 1997; 25: 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Van der Lee J, Bakker TJEM, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Multivariate models of subjective caregiver burden in dementia: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev 2014; 15: 76–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. George LK, Gwyther LP. Caregiver well-being: a multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. Gerontologist 1986; 26: 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.