Abstract

Background

In the United States, perceptions of marijuana’s acceptability are at an all-time high, risk perceptions among youth are low, and rates are rising among Black youth. Thus, it is imperative to increase the understanding of long-term effects of adolescent marijuana use and ways to mitigate adverse consequences.

Objectives

To identify the midlife consequences of heavy adolescent marijuana use and the mechanisms driving effects among a Black, urban population.

Methods

This study analyzed the propensity score-matched prospective data from the Woodlawn Study, a community cohort study of urban Black youth followed from ages 6–42. After matching the 165 adolescents who used marijuana heavily to 165 non-heavy/nonusers on background confounders to reduce selection effects (64.5% male), we tested the association of heavy marijuana use by age 16 with social, economic, and physical and psychological health outcomes in midlife and the ability of adult drug trajectories (marijuana, cocaine, and heroin use from ages 17–42) and school dropout to mediate effects.

Results

Heavy adolescent marijuana use was associated with an increased risk of being poor and of being unmarried in midlife. Marijuana use also predicted lower income and greater anxious mood in midlife. Both adult drug use trajectories and school dropout significantly mediated socioeconomic effects but not marital or anxious mood outcomes.

Conclusion

Heavy adolescent marijuana use seems to set Black, urban youth on a long-term trajectory of disadvantage that persists into midlife. It is critical to interrupt this long-term disadvantage through the prevention of heavy adolescent marijuana use, long-term marijuana and other drug use, and school dropout.

Keywords: African Americans, cannabis, marijuana effects, mechanisms, substance use trajectories, urban youth

The acceptability of marijuana use among Americans has never been higher; 2014 marked the first year that the majority of Americans favored marijuana legalization (1). Moreover, perceptions of harm continue to decrease dramatically among adolescents; currently, less than one-third of 12th graders perceive great risk in regular marijuana use (2). These changes are accompanied by increasing rates of use among certain subgroups. Historically, Black youth have used marijuana at lower rates than White youth, but, recently, rates for Black youth have risen and surpassed White youth (3–5). Further, national data suggest that annual marijuana use is highest in large metropolitan statistical areas (5), suggesting Black urban youth may be a particularly vulnerable population. Despite favorable attitudes toward marijuana overall and increasing use among Black youth in particular, there is a dearth of studies that examine the life course impact of marijuana for this population and reasons for long-term effects.

Previous work has shown that heavy involvement with marijuana during adolescence is likely to have a wealth of consequences that persist through young adulthood with evidence from review articles (6–9), as well as studies with disadvantaged urban minority cohorts (10–12). Specifically, heavy adolescent marijuana use seems to decrease participation in school and marriage; lead to lower income; and increase the risk for unemployment, nonmarital births, mental health problems, and substance use problems in young adulthood (11,13–17). Yet, whether these consequences extend beyond young adulthood and into midlife and the specific mechanisms over time that drive social, economic, and mental health effects in midlife have yet to be studied in any depth.

From the life course perspective, individuals’ development is shaped by a series of long-term trajectories and embedded within these trajectories are short-term discrete life events that can redirect a trajectory (18,19). For adolescents, marijuana use can redirect any number of interlocking trajectories such as social role development, financial security, and physical and mental health. Moreover, according to the life course perspective’s theoretical notion of cumulative disadvantage (20–22), heavy marijuana use can perpetuate or accentuate the existing trajectories of disadvantage such that adversities accumulate over time “with one hardship remaining present and the next building on top of it in a cascading sequence” (23). We focus on exposure to marijuana during adolescence in accordance with the life course framework’s emphasis on past experiences as integral to one’s future life course development.

For instance, within the same developmental period, one of the most consistent outcomes linked to adolescent marijuana use is interruptions of education (see 24 for a review). Studies have found adolescent marijuana use to affect high school graduation (25,26), as well as the likelihood of entering college (26,27). Educational effects are particularly prominent for those who first used marijuana before age 15 (26).

In accordance with the life course principle of homotypic continuity, much evidence exists supporting the continuation and escalation of substance use as one moves out of adolescence into adulthood (28,29). A number of researchers have examined the trajectories of marijuana over time and attributed negative outcomes to long-term patterns of use (30–32). For example, among a sample of men who spent their childhood in a high crime neighborhood of a medium-sized metropolitan area, Washburn and Capaldi (2015) (32) found that long-term, chronic marijuana use throughout the 20s was related to depression, antisocial behavior, antisocial peer affiliations, and lower likelihood of marriage in their mid-30s compared to those in the little/no use trajectory. Similarly, Brook and colleagues (10), in a sample of urban youth followed to young adulthood, found that chronic and late-onset groups had a greater likelihood of work problems, depressive symptoms, and criminal behavior in young adulthood compared to low/nonuse groups. Interestingly, early-onset users who declined in use during their 20s had a greater likelihood of anxiety symptoms, marital discord, and criminal behavior in young adulthood compared to late-onset users, suggesting the detrimental impact of early marijuana use at high rates even if use does not continue. As these trajectory studies focused on marijuana over significant portions of the life course, less is known about trajectories of use of multiple drugs and how multidrug use trajectories contribute to long-term negative outcomes. With these types of studies, selection effects remain a concern.

Because of evidence suggesting that adolescent marijuana use increases the risk of school dropout and promotes continuation or escalation of substance use over the long-term and our theoretical understanding of how adversities accumulate over time, it is critical at this time when nations debate policies that expand marijuana access to better understand the mechanisms connecting adolescent marijuana use with later outcomes. It is particularly important to study these mechanisms and consequences in vulnerable populations. The specific research questions are (1) what are the negative consequences of heavy adolescent marijuana use that extend into midlife, (2) does resulting educational failure mediate long-term effects, and (3) do drug use patterns across young adulthood mediate midlife effects? We hypothesize that heavy involvement with marijuana use leads adolescents away from educational pursuits and puts them on a pathway of long-term use, which drive negative effects that extend throughout the life course.

Methods

Sample

This study uses data from the Woodlawn Study, a prospective community cohort study of urban Black population followed from ages 6–42. Woodlawn is one of 76 community areas in Chicago. The study began in 1966 recruiting the entire cohort of first graders from the Woodlawn community area’s nine public and three private schools. Only 13 families declined participation. At that time, Woodlawn was characterized by high rates of female-headed households and poverty; however, socioeconomic diversity existed within the community due to racial segregation in Chicago at that time (see 33).

In the first grade (age 6, N = 1242), mothers (or mother surrogates) completed in-depth, in-person interviews about their children’s health, behavior, family life, and home environment. Teachers reported on school performance and behavior. In adolescence (age 16, n = 705), mothers and teenagers were assessed on similar domains. Only youth who remained in the Chicago area were contacted for participation. In young (age 32, n = 952) and mid-adulthood (age 42, n = 833), attempts were made to interview all cohort members regardless of adolescent participation. Cohort members participated in in-depth interviews assessing health, substance use, criminal behavior, and social integration, among other things. School, criminal, and death records have been collected over time. This analysis begins with the 633 individuals who had complete adolescent marijuana data and any substance use data in adulthood. This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each authors’ university.

Measures

Adolescents self-reported frequency of marijuana use in six categories: never used, 1–2 times, 3–9 times, 10–19 times, 20–39 times, and 40 or more times. We defined heavy adolescent marijuana use as use 20 times or more by age 16 (see 11). Heavy users are compared to peers with light or no use (19 times or less).

The dependent variables include indicators of socioeconomic status, social role performance, physical and mental health, and are self-reported at the midlife assessment. Household income was reported on an 18-point scale (1 = under $1000 and 18 = $100,000 or more). Poverty status was calculated based on Federal guidelines according to participants’ household income for the previous year and household size. Participants self-reported their current marital status, allowing us to compare those who were living with a partner and those unmarried (i.e., never married, divorced, separated, widowed) to those who were currently married. Participants self-reported their current employment status. Employed individuals include those reporting working full-time, part-time, more than one job, or being with a job, but temporarily ill, on vacation, or on strike the week prior to the interview. Unemployed individuals include those who reported being unemployed, laid off, looking for work, retired, in school, keeping house, disabled or “other” who did not report meeting any of the employment criteria.

Anxious mood is derived from the mean of seven items assessing the degree to which participants felt nervous, tense, under pressure, tight inside, tense in new situations, have hands that sometimes shake, and startle easily, measured on the 6-point How I Feel scale (1 = not at all, 6 = very, very much, mean = 1.78, α = 0.85, see 34). Because the distribution was highly skewed, we created a dichotomous variable representing higher (≥2.5) and lower (<2.5) anxious mood. Suicidality is a count of affirmative responses to five questions (range 0–5) assessing thinking a lot about death, thinking it would be better if you were dead, thinking about suicide, making a suicide plan, and making a suicide attempt based on items from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (UMCIDI, 35) assessment of depression. The scale was administered to all participants regardless of their responses to the depression screener. We compared those with a score of two or higher with those with fewer than two endorsed items. Self-rated health was assessed on a 5-point scale from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent. Because of a skewed distribution, we compared those with poor or fair health to those with good, very good, or excellent health.

Mediators

Adult drug patterns were based on self-reported use of marijuana, cocaine, and heroin between ages 17–42. A sum of the number of drug types used was calculated (range = 0–3 substances) for each age (ages 17–42). Educational level was based on self-reports in the young adult interview and supplemented with school records and midlife interview data. We categorized individuals into three groups: high school dropouts, GED/HS diploma, and college degree or higher.

Confounders

Eighteen childhood and adolescent confounders included child’s gender; female-headed household; household poverty status; mothers’ years of education, self-rated depressed mood, drug and alcohol use, and school aspirations for her child; childhood family punishment; from the school: IQ, 1st grade reading scores, 1st grade teacher ratings of shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and classroom conduct; and adolescent self-reports of family conflict, violent offenses, property offenses, alcohol use, and smoking.

Analytic plan

In Step 1, we applied propensity score matching (36). We implemented this approach to reduce selection effects and estimate potential causal effects, as regression on a matched sample has been shown to have advantages over standard regression with covariate adjustment when estimating causal effects in observational data (37–39). Propensity scores were estimated for each individual based on the 18 confounders. Using nearest neighbor matching, the 165 adolescents who used marijuana heavily were matched to 165 non-heavy/nonusers based on these propensity scores. (The 303 individuals who were not matched were omitted from further analyses.)

In Step 2, we examined the longitudinal patterning of drug use from ages 17–42 using semi-parametric group-based modeling (40). Specifically, we estimated a quadratic, mixed Poisson model based on the number of drug types used at each age and determined the optimal model based on model diagnostics (i.e., the BIC, average posterior probability, odds of correct classification), as well as parsimony of the model. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to account for missing data.

In Step 3, we assessed mediation by calculating Sobel statistics to test the statistical significance of the indirect effect (41). We only tested mediation when there was a statistically significant total effect and a significant association between heavy adolescent marijuana use and the mediators, as well as an association between the mediator of interest and the outcome (p < 0.05). All models relied on adjusted regression on the matched sample to ensure double robustness (38). Linear regression was used for income; logistic regression for employment status, poverty, suicidality, anxious mood, and self-rated health; and multinomial regression for educational attainment, drug trajectories, and marital status. We report percent of the effect that is mediated, as well as Sobel test p-values.

Mediation testing relies on multiply imputed data. We conducted multiple imputation for the minimal missing in the baseline covariates and to account for missingness on midlife outcomes due to attrition. This approach has been shown to reduce bias compared to analysis of complete data (42,43). Multiple imputation was conducted in Stata/SE 11.2 imputing 40 datasets to maximize power (44).

Results

Attrition analyses

Before addressing our research questions, we assessed attrition comparing those who completed the adolescent assessment (n = 705) with those missing in adolescence (n = 537). Analyses revealed no differences on sex, childhood poverty status, welfare receipt, family structure in the home, or early social adaptational status. Nor did they differ on having an official adult arrest record in adulthood. Individuals not assessed in adolescence were more likely to have dropped out of high school and to have low first-grade math scores. We also compared the 633 adolescents who were interviewed in adulthood with the 72 adolescents who were missing adult data and found no differences on all the aforementioned background (except family structure) or on adolescent marijuana use. They again did, however, have significantly higher rates of school dropout; they were also slightly more likely to come from a single mother household (p = 0.066).

Step 1: Propensity score matching

Before matching, we found that adolescents who used marijuana heavily and non-heavy adolescent marijuana users/nonusers were significantly different (p < 0.05) on 8 of the 18 background variables before matching and none after matching. Further, after matching, we found no significant differences, as well as no standardized biases greater than 0.20, suggesting adequate balance on observed covariates between heavy and non-heavy adolescent marijuana users. In fact 11 of the 18 were less than 0.10, suggesting excellent balance. Table 1 provides midlife characteristics of the matched sample, demonstrating high rates of poverty and low rates of marriage in this sample.

Table 1.

Midlife characteristics of Woodlawn matched sample (n = 330).

| Midlife variables | Percent |

|---|---|

| Marital status | |

| Never marrieda | 36.51 |

| Separated/divorced/widoweda | 23.02 |

| Living with a partner | 11.11 |

| Married | 29.37 |

| Employed past week | 61.83 |

| Living below the poverty line | 35.27 |

| Annual household incomeb | |

| Less than $25,000 | 56.29 |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 19.21 |

| $50,000 or more | 24.51 |

| Endorsed two or more suicide symptoms | 27.26 |

| Higher anxious mood (2.5 or higher) | 26.46 |

| Fair/poor self-rated health | 24.28 |

Those who were never married were combined with those who were separated, divorced, or widowed to create an unmarried category for regression analyses.

Income was modeled as a continuous variable in regression analyses.

Step 2: Identifying drug trajectories

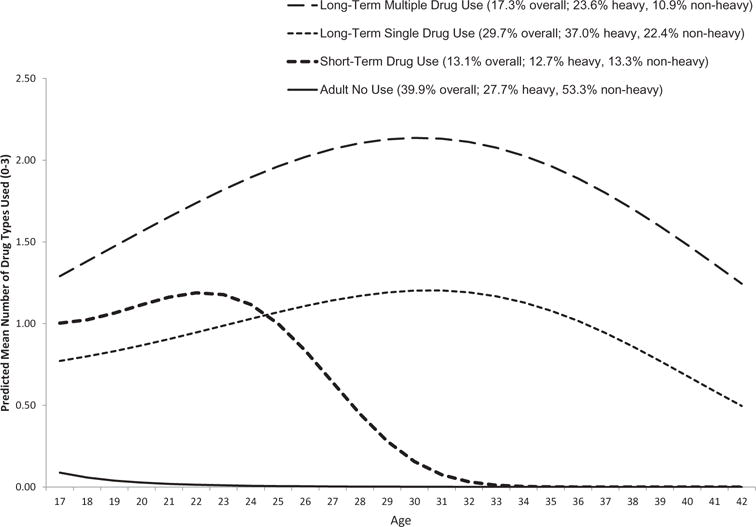

We identified four substance use trajectories: adult non-use (39.9%), short-term use (13.1%), long-term single-drug use (29.7%) and long-term multiple-drug use (17.3%), as shown in Figure 1. The majority of non-heavy adolescent marijuana users were in the nonuse trajectory (53.3%), while the majority of adolescents who used marijuana heavily were in one of the two long-term use trajectories (37.0% single-drug use, 23.6% multiple-drug use). Slightly more than one-quarter of adolescents who used marijuana heavily were in a nonuse trajectory in adulthood and 12.7% are in the short-term use trajectory.

Figure 1.

Substance use trajectories for Woodlawn cohort matched sample, ages 17 to 42 (n = 330).

Step 3a: Association of adolescent marijuana use on drug trajectories

Table 2 shows the association of adolescent marijuana use and adult drug trajectories. Adolescents who used marijuana heavily were 3.68 times as likely as non-heavy users to be in the long-term single-drug use trajectory and 4.70 times as likely to be in the long-term multiple-drug use trajectory than in the nonuse trajectory (p’s<0.001). Adolescents who used marijuana heavily were 2.74 times as likely to be in the long-term multiple-drug use trajectory than the short-term drug use trajectory (p = 0.026).

Table 2.

Association of heavy adolescent marijuana use with drug trajectories.

| Heavy adolescent marijuana user | Non-heavy adolescent marijuana user/nonuser | Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval | Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval | Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Nonuse | 26.67% | 53.33% | Reference | 0.583 (0.275–1.238) |

0.272 (0.152–0.485) |

| Short-term drug use | 12.73% | 13.33% | 1.714 (0.808–3.639) |

Reference | 0.466 (0.211–1.026) |

| Long-term single-drug use | 36.97% | 22.42% | 3.681 (2.060–6.576) |

2.147 (0.975–4.729) |

Reference |

| Long-term multiple-drug use | 23.64% | 10.91% | 4.679 (2.287–9.648) |

2.740 (1.129–6.653) |

1.276 (0.613–2.655) |

Note: Heavy and non-heavy users are matched on gender; household structure; poverty status; maternal education; maternal depressed mood; maternal drug and alcohol use; maternal school aspirations for her child; childhood family punishment; IQ; reading scores; teacher ratings of shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and classroom conduct; and adolescent self-reports of family conflict, violent and property offenses, alcohol use, and smoking in order to control for the influence of these confounders.

Step 3b: Association of adolescent marijuana with educational attainment

As shown in Table 3, adolescents who used marijuana heavily were over three times as likely as light/nonusers to drop out of school than to obtain a college degree (OR = 3.11, p = 0.010) and less likely to obtain a high school diploma/GED compared to dropping out of school (OR = 0.49, p = 0.029).

Table 3.

Association of heavy adolescent marijuana use with education.

| Heavy adolescent marijuana user | Non-heavy adolescent marijuana user/nonuser | Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval | Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High school dropout | 29.11% | 17.20% | 3.112 (1.311–7.388) |

Reference |

| GED/HS Diploma | 58.59% | 63.20% | 1.523 (0.762–3.044) |

0.489 (0.258–0.929) |

| College degree | 12.30% | 19.61% | Reference | 0.321 (0.135–0.763) |

Note: Heavy and non-heavy users are matched on gender; household structure; poverty status; maternal education; maternal depressed mood; maternal drug and alcohol use; maternal school aspirations for her child; childhood family punishment; IQ; reading scores; teacher ratings of shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and classroom conduct; and adolescent self-reports of family conflict, violent and property offenses, alcohol use, and smoking in order to control for the influence of these confounders.

Step 4: Association of adolescent marijuana and mediators with midlife outcomes

As shown in Table 4, adolescents who used marijuana heavily were 1.8 times as likely as non-heavy/ nonusers to be unmarried compared to married in midlife (p = 0.048). Dropping out of high school mediated 32% of this association, but this was not statistically significant according to the Sobel statistic (p = 0.180); adult drug trajectories were not related to marital status. Although no association existed between adolescent marijuana use and midlife employment status (OR = 0.925, 95% CI = 0.507–1.689), adolescents who used marijuana heavily were almost twice as likely as light/nonusers to be poor at age 42 (p = 0.032). Dropping out of high school mediated 45% of the total effect (p = 0.066), while adult drug trajectories mediated an additional 34% (p = 0.047). Adolescents who used marijuana heavily also had lower income at midlife (b = −1.43, p = 0.018) again with 45% of the effect mediated by high school dropout (p = 0.060) and 43% mediated by adult drug trajectories (p = 0.047).

Table 4.

Association of heavy adolescent marijuana use with adult outcomes: regression estimates and p-values for the propensity score matched sample.

| Midlife outcome | Total effect B 95% confidence interval (CI) | Percent of the effect mediated by high school dropout, p-valuea | Percent of the effect mediated by adult drug trajectories, p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomec | −1.429 (−2.611 to –0.246) | 45.08%, p = 0.060b | 42.61%, p = 0.005 |

|

| |||

| Odds ratio (OR) 95% CI |

|||

|

| |||

| Poverty | |||

| No | Reference | 44.65%, p = 0.066 b | 34.38%, p = 0.047c |

| Yes | 1.965 (1.059–3.646) | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Married | Reference | ||

| Unmarried | 1.785 (1.005–3.171) | 32.00% p=0.180 | |

| Living with partner | N/A | ||

| Anxious mood | 1.304 (0.488–3.614) | ||

| Low | Reference | N/A | 28.45%, p = 0.107 |

| High | 2.118 (1.002–4.476) | ||

Note: All models adjust for gender; household structure; poverty status; maternal education; maternal depressed mood; maternal drug and alcohol use; maternal school aspirations for her child; childhood family punishment; IQ; reading scores; teacher ratings of shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and classroom conduct; and adolescent self-reports of family conflict, violent and property offenses, alcohol use, and smoking. The anxious mood model also controls for young adult anxious mood (age 32), which is the same variable as the outcome.

N/A = Mediation model not tested because there was not a statistically significant association between the mediator and the outcome.

p-Value based on Sobel test (1982).

Control for adult drug trajectories.

Controls for high school dropout.

While there was no association between heavy adolescent marijuana use and suicidality (OR = 1.211, 95% CI = 0.594–2.470), we did see greater anxious mood in midlife among adolescents who used marijuana heavily (OR = 2.118, p = 0.049); neither school dropout or drug trajectories significantly mediated this effect. Last, adolescents who used marijuana heavily were almost twice as likely than non/light users to have fair/poor health in midlife compared to excellent to good health; however, this association was not statistically significant (OR = 1.894, 95% CI = 0.889–4.042).

Discussion

Findings come from a prospective, community cohort study of urban Black youth, followed from first grade (age 6) through midlife (age 42). By studying a cohort since childhood, we were able to better isolate the impact of marijuana use from that of shared risk factors, such as tobacco and alcohol use and delinquency, all the while ensuring proper temporal ordering between marijuana use, mechanisms, and consequences. The focus on Black youth allowed us to study this topic among a highly relevant population.

Overall findings suggest that the consequences of adolescent marijuana use for urban youth are broad and extend into midlife. In particular, what we termed “heavy adolescent marijuana use” (i.e., use 20 times or more by age 16) seems to increase the likelihood of being unmarried, living below the poverty line, having a lower income, and feeling more anxious in midlife (age 42). This level of use represented the top quartile of use.

To better understand the possible intermediary processes driving negative consequences 25 years after the marijuana use begins, we tested two potential mechanisms, namely high school dropout and adult drug trajectory. Evidence suggests that both mechanisms may be part of the pathway linking heavy adolescent marijuana use and negative adult outcomes in midlife. Specifically, drug trajectories mediated 34% of adolescent marijuana uses’ total effect on poverty and 43% of the effect on income. Thus, these statistically significant results suggest that socioeconomic consequences of adolescent marijuana use, in particular, are driven in part by the long-term course of substance use on which adolescent marijuana may launch an individual. Similarly, high school dropout mediated 45% of the total effect of adolescent marijuana use on poverty and on income, but both statistics were marginally significant and require replication. Neither school dropout nor long-term drug patterns seem to drive anxious mood or marital effects; so additional mechanisms should be explored.

We found no association between adolescent marijuana use and physical health in the 40s. It may be that health effects take longer to materialize or more specific outcomes (e.g., lung functioning) should be examined. We also did not find a link with suicidality, in contrast to previous work (17,45). Perhaps through propensity score matching, the analytic technique we applied in an attempt to isolate the consequences of marijuana use, we were better able to account for selection effects than previous work. Alternatively, a relatively weak association may exist that our small sample size was not able to detect or this association is more relevant for other populations. Finally, we found no association with unemployment. While previous work with the Woodlawn cohort found an association between adolescent marijuana use and unemployment in young adulthood (11), our results suggest that the effect does not seem to extend later in the life course and might be limited to aspects of work beyond employment, such as work quality.

Results suggest that the low risk perceptions of marijuana use among youth in the United States (5) may be short-sighted, at least for disadvantaged urban youth. Parents, youth, and service providers need to be aware of evidence suggesting long-term negative effects, particularly the strong association between adolescent marijuana, school dropout, and long-term trajectories of drug use, which we demonstrated in this study and which other studies have found (8). Preventing school dropout and reducing the association of adolescent marijuana use with long-term drug trajectories is critical as these relationships seem to drive other negative adult outcomes 25 years later. As voters consider initiatives to make marijuana more widely available, it is imperative that the general public be aware of potential long-term harms to vulnerable populations and identify ways to redirect negative pathways, as purported by the life course perspective (18).

While the study has numerous strengths including the prospective design spanning 35 years, the use of an at-risk community cohort, and the incorporation of propensity score matching to isolate consequences, there are a number of limitations that should be mentioned. First, in adolescence, we were only able to examine the total number of times marijuana had been used and could not study daily use, which has been shown to potentially put individuals at greatest risk of negative outcomes (17) and has remained consistently high in recent years (5). Additionally, although validation analyses indicate that the drug trajectories capture general patterns of substance use over time (e.g., comparisons of trajectory group with adult frequency measures and criteria for substance abuse), these trajectories were unable to capture periods of abstinence or quantity of use. Further, despite the use of propensity score matching, causal effects must be interpreted with caution. In addition, other potential mechanisms exist that we were not able to study, such as impaired cognitive functioning as a result of marijuana-induced changes to the adolescent brain (46,47).

Another important consideration is the generalizability of the findings. From a theoretical point of view, the notion of cumulative adversity suggests that a more vulnerable population like the Woodlawn Study participants who have experienced unequally distributed disadvantages throughout the life course may have worse consequences from marijuana than those from more protective environments. Thus, whether negative effects identified here translate to other populations is a question for future research. Moreover, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content, the main active ingredient in marijuana, has risen dramatically over time (48), suggesting that the consequences may be worse for today’s youth than those of the past (9). Further, the Woodlawn study suffered from substantial attrition in adolescence as only those who remained in the Chicago area were assessed. As school dropout related to follow-up in adulthood and heavy adolescent marijuana use related to school dropout, we may have underestimated the negative consequences.

Results contribute to the growing research base on the consequences of adolescent marijuana use and identify two mechanisms leading to long-term effects. Findings provide evidence that marijuana use by vulnerable adolescents is not benign. In fact, it seems to lead to school dropout and set individuals on a course of substance use that lasts through adulthood, with socioeconomic consequences 25 years later. While preventing marijuana use among adolescents offers the most promise for reducing negative consequences, findings suggest that the prevention of school dropout and long-term drug use among heavy adolescents users offers the chance to mitigate some long-term effects. Expanding and increasing the effectiveness of substance use treatment, as well as greater drug screening, for adolescents should be a priority. Thus, as the United States becomes increasingly marijuana friendly, it is crucial to ensure that marijuana commercialization policies carefully consider and monitor impact on adolescents (see 49) with the hopes that expanded access to marijuana in general does not lead to expanded marijuana-related problems for youth as this work demonstrates serious and long-lasting effects of early, heavy use.

Acknowledgments

We are especially grateful to these original researchers, the Woodlawn study participants, Woodlawn Advisory Board, and all of the researchers who have been instrumental in creating and maintaining this rich dataset.

Funding

This study uses data from the Woodlawn project, which was designed and executed by Shepphard Kellam and Margaret Ensminger and funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) and other NIH institutes. This particular study was funded by NIDA’s R01DA03399 (Doherty, PI).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest declaration

None.

References

- 1.Swift A. For first time, Americans favor legalizing marijuana. 2013 Oct 22; Available from: http://www.gallup.com/poll/165539/first-time-americans-favor-legalizing-marijuana.aspx [accessed 3 March 2014]

- 2.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2016. Monitoring the Future national results on drug use: 1975–2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson RM, Fairman B, Gilreath T, Xuan Z, Rothman EF, Parnham T, Furr-Holden DM. Past 15-year trends in adolescent marijuana use: Differences by race/ethnicity and sex. Drug Alcoh Depend. 2015;155:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, Dziack JJ, Butera NM. Trends among US high school seniors in recent marijuana use and associations with other substances: 1976–2013. J Adoles Health. 2015;57:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2016. Monitoring the Future national results on drug use: 1975–2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374:1383–1391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karila L, Roux P, Rolland B, Benyamina A, Reynaud M, Aubin HJ, Lancon C. Acute and long-term effects of cannabis use: a review. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:4112–4118. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macleod J, Oakes R, Copello A, et al. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. Lancet. 2004;363:1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SRB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brook JS, Jung YL, Brown EN, Finch SJ, Brook DW. Developmental trajectories of marijuana use extending from adolescence to adulthood: Personality and social role outcomes. Psychol Rep. 2011;20:339–357. doi: 10.2466/10.18.PR0.108.2.339-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green KM, Ensminger ME. Adult social behavioral effects of heavy adolescent marijuana use among African Americans. Dev Psych. 2006;42:1168–78. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green KM, Musci RJ, Johnson RM, Matson PA, Reboussin BA, Ialongo NS. Outcomes associated with adolescent marijuana and alcohol use among urban young adults: A prospective study. Addict Behav. 2016;53:155–160. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Hall W. Cannabis use and mental health in young people: cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325:1195–1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fergusson DM, Boden JM. Cannabis use and later life outcomes. Addiction. 2008;103:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green KM, Doherty EE, Stuart EA, Ensminger ME. Does heavy adolescent marijuana use lead to criminal involvement in adulthood? Evidence from a multiwave longitudinal study of urban African Americans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brook JS, Lee JY, Finch SJ, Seltzer N, Brook DW. Adult work commitment, financial stability and social environment as related to trajectories of marijuana use beginning in adolescence. Subst Abus. 2013;34:298–305. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.775092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silins E, Horwood LJ, Patton GC, Fergusson DM, Olsson CA, Hutchinson DM, et al. Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: an integrative analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:286–293. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elder GH. Life course dynamics: Trajectories and transitions 1968–1980. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elder GH. The life course as developmental theory. Child Dev. 1998;69:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dannefer D. Aging as intracohort differentiation: accentuation, the Matthew Effect, and the life course. Sociol Forum. 1987;2:211–236. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preston SH, Hill ME, Drevenstedt GL. Childhood conditions that predict survival to advanced ages among African-Americans. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1231–1246. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. A life-course theory of cumulative disadvantage and stability of delinquency. In: Thornberry TP, editor. Developmental theories of crime and delinquency Advances in criminological theory. Vol. 7. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1997. pp. 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatch SL. Conceptualizing and identifying cumulative adversity and protective resources: implications for understanding health inequalities. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:S130–S134. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynskey M, Hall W. The effects of adolescent cannabis use on educational attainment: a review. Addiction. 2000;95:1621–1630. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ, Saner H. Antecedents and outcomes of marijuana use initiation during adolescence. Preventive Med. 2004;39:976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM, Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Coffey C, Patton GC, Hutchinson DM. Cannabis use and educational achievement: Findings from three Australasian cohort studies. Drug Alcoh Depend. 2010;110:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL. Cannabis and educational achievement. Addiction. 2003;98:1681–1692. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen CY, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Early-onset drug use and risk for drug dependence problems. Addict Behav. 2009;34:319–322. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anthony JC, Petronis, KR Early-onset drug use and risk of later drug problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;40:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brook JS, Zhang C, Leukefeld CG, Brook DW. Marijuana use form adolescence to adulthood: Developmental trajectories and their outcomes. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidem. 2016:511405–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juon HS, Fothergill KE, Green KM, Doherty EE, Ensminger ME. Antecedents and consequences of marijuana use trajectories over the life course in an African American population. Drug Alcoh Depend. 2011;118:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Washburn IJ, Capaldi DM. Heterogeneity in men’s marijuana use in the 20s: Adolescent antecedents and consequences in the 30s. Dev Psychopathol. 2015;27:279–291. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kellam SG, Branch JD, Agrawal KC, Ensminger ME. Mental health and going to school: The Woodlawn program of assessment, early intervention and evaluation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen AC, Kellam SG. Measurement of psychological well-being of adolescents: the psychometric properties and assessment procedures of the How I Feel. J Youth Adolesc. 1977;6:229–247. doi: 10.1007/BF02138937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H-U, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drake C. Effects of misspecification of the propensity score on estimators of treatment effects. Biometrics. 1993;49:1231–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Anal. 2007;15:199–236. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin DB, Thomas N. Combining propensity score matching with additional adjustments for prognostic covariates. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:573–85. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagin DS. Group-based modeling of development over the life course. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models In S Leinhardt ed Sociological Methodology. Washington DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:549–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data, our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97:1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Batalla A, Bhattacharyya S, Yucel M, et al. Structural and functional imaging studies in chronic cannabis users: a systematic review of adolescent and adult findings. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2657–E2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLaren J, Swift W, Dillon P, Allsop S. Cannabis potency and contamination: a review of the literature. Addiction. 2008;103:1100–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pacula RL, Kilmer B, Wagenaar AC, Chaloupka FJ, Caulkins JP. Developing public health regulations for marijuana: lessons from alcohol and tobacco. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1021–1028. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]