Abstract

Background

The factors influencing three major outcomes–death, stroke/systemic embolism (SE), and major bleeding–have not been investigated in a large international cohort of unselected patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation (AF).

Methods and results

In 28,628 patients prospectively enrolled in the GARFIELD-AF registry with 2-year follow-up, we aimed at analysing: (1) the variables influencing outcomes; (2) the extent of implementation of guideline-recommended therapies in comorbidities that strongly affect outcomes. Median (IQR) age was 71.0 (63.0 to 78.0) years, 44.4% of patients were female, median (IQR) CHA2DS2-VASc score was 3.0 (2.0 to 4.0); 63.3% of patients were on anticoagulants (ACs) with or without antiplatelet (AP) therapy, 24.5% AP monotherapy, and 12.2% no antithrombotic therapy. At 2 years, rates (95% CI) of death, stroke/SE, and major bleeding were 3.84 (3.68; 4.02), 1.27 (1.18; 1.38), and 0.71 (0.64; 0.79) per 100 person-years. Age, history of stroke/SE, vascular disease (VascD), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) were associated with the risks of all three outcomes. Congestive heart failure (CHF) was associated with the risks of death and stroke/SE. Smoking, non-paroxysmal forms of AF, and history of bleeding were associated with the risk of death, female sex and heavy drinking with the risk of stroke/SE. Asian race was associated with lower risks of death and major bleeding versus other races. AC treatment was associated with 30% and 28% lower risks of death and stroke/SE, respectively, compared with no AC treatment. Rates of prescription of guideline-recommended drugs were suboptimal in patients with CHF, VascD, or CKD.

Conclusions

Our data show that several variables are associated with the risk of one or more outcomes, in terms of death, stroke/SE, and major bleeding. Comprehensive management of AF should encompass, besides anticoagulation, improved implementation of guideline-recommended therapies for comorbidities strongly associated with outcomes, namely CHF, VascD, and CKD.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01090362

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most frequent of all sustained cardiac arrhythmias, is associated with increased risk of death, stroke/systemic embolism (SE), and bleeding. Currently recommended management approaches include rhythm and/or rate control, and anticoagulation for the prevention of stroke/SE in at-risk patients without contraindication [1, 2]. We previously showed in the Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD–Atrial Fibrillation (GARFIELD-AF) registry that at 2-year follow-up, death was the most frequent major adverse event, occurring at a much higher rate than stroke/SE or major bleeding [3]. Stroke-related death accounted for less than 10% of all causes of death.

In this report, we analyse at 2-year follow-up the outcomes of 28,628 patients with newly diagnosed AF recruited in the first three cohorts of GARFIELD-AF, with two objectives. The primary objective was to identify the variables associated with the risks of all three major outcome measures, namely death, stroke/SE and bleeding, particularly those linked to modifiable risk factors. The secondary objective was to assess compliance with guidelines as regards drug prescription in comorbidities identified to strongly affect outcomes, namely congestive heart failure (CHF), vascular disease (VascD), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [4–6].

Methods

The design of the GARFIELD-AF registry was reported previously [7, 8]. Briefly, men and women aged ≥18 years with non-valvular AF diagnosed according to standard local procedures within the previous 6 weeks, and with at least one non-prespecified risk factor for stroke as judged by the investigator, were eligible for inclusion [8].

Patients were enrolled prospectively and consecutively. Investigator sites were selected randomly (apart from 18 sites) and represent the different care settings in each participating country (office-based practice; hospital departments including neurology, cardiology, geriatrics, internal medicine and emergency; anticoagulation clinics; and general or family practice) [7, 8].

Ethics statement

Independent ethics committee and hospital-based institutional review board approvals were obtained. A list of central ethics committees and regulatory authorities that provided approval can be found in S2 File. Additional approvals were obtained from individual study sites. The registry is being conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, local regulatory requirements, and the International Conference on Harmonisation–Good Pharmacoepidemiological and Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent is obtained from all study participants. Confidentiality and anonymity of all patients recruited into this registry are maintained.

Procedures and outcome measures

Baseline characteristics collected at inclusion in the registry included medical history, care setting, type of AF, date and method of diagnosis, symptoms, antithrombotic treatment (vitamin K antagonists [VKAs], non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants [NOACs], and antiplatelet [AP] treatment), as well as all cardiovascular drugs. Race was classified by the investigator in agreement with the patient [8]. Data on components of the CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED risk stratification schemes were collected to assess the risks of stroke and bleeding retrospectively. HAS-BLED scores were calculated excluding fluctuations in international normalised ratio.

Collection of follow-up data occurred at 4-monthly intervals up to 24 months [7, 8]. Standardised definitions for clinical events have been reported previously [7, 8]. In brief, baseline characteristics and treatments, and the incidence of death (cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular), stroke/SE, and bleeding were recorded. Submitted data were examined for completeness and accuracy by the coordinating centre (Thrombosis Research Institute, London, UK), and data queries were sent to study sites. GARFIELD-AF data are captured using an electronic case report form (eCRF). In accordance with the study protocol, 20% of all eCRFs are monitored against source documentation [9].

Data for the analysis in this report were extracted from the study database on 28 July 2016.

Definitions

VascD included peripheral artery disease or coronary artery disease with a history of acute coronary syndromes (ACS). CKD was classified according to National Kidney Foundation guidelines into two groups: moderate-to-severe (stages 3–5), or mild (stages 1 and 2) or none [6]. CHF was defined as current/prior history of CHF or left ventricular ejection fraction of <40%.

Guideline-recommended therapies included angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), betablockers, aldosterone blockade, and loop diuretics for CHF; aspirin (ASA), statins, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, and betablockers for VascD; and ACE inhibitors/ARBs for CKD.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR) and categorical variables as frequency and percentage. Baseline rates of prescription of guideline-recommended drugs in CHF, VascD, and CKD are displayed with the baseline rate of prescription of anticoagulants (ACs).

Differences in medians were tested using the Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test. Differences in proportions were tested using the two-sample test of proportion. Trends were assessed using an extension of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Occurrence of major clinical outcomes is expressed as person-time event rates (per 100 person-years) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Person-year rates were estimated using a Poisson model with the number of events as the dependent variable and the log of time as an offset, i.e., a covariate with a known coefficient of 1. Only the first occurrence of events was taken into account. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs were estimated using a proportional hazards Cox model based on five imputed datasets. The imputed datasets were created by the Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) algorithm [10, 11]. The proportional hazard assumption was assessed visually using plots of the survivor function. The following variables were included in the Cox model: age groups (<65, 65–69, 70–74, ≥75 years), gender, race (Caucasian/Hispanic/Latino, Asian, other race–including Afro-Caribbean, mixed/other, and unwilling to declare/not recorded), smoking (no, ex, current), diabetes, hypertension, previous stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA)/SE, history of bleeding, cardiac failure, VascD, moderate-to-severe renal disease, AC treatment, type of AF (new onset [unclassified], paroxysmal, persistent, permanent), and alcohol consumption (abstinent, light, moderate, heavy). Hazard ratios were adjusted for all variables in the model.

Data analysis was performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata Statistical Software: Release 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Forest plots were created in R 3.3.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study population

The study population comprised 28,628 prospective patients with AF enrolled in GARFIELD-AF between March 2010 and October 2014 and followed for 2 years. Patients came from 1048 study sites representative of routine practice in each of 32 countries. Two-year follow-up was achieved in 91% of patients. At baseline, the median (IQR) age was 71.0 (63.0 to 78.0) years and 44.4% of patients were female. The median (IQR) CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores were 3.0 (2.0 to 4.0) and 1.0 (1.0 to 2.0), respectively. Other baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. At diagnosis of AF, 63.3% of patients were prescribed AC therapy (46.3% VKAs and 17.0% NOACs, with or without APs), 24.5% received AP monotherapy, and 12.2% received no AC or AP therapy.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of all patients (N = 28,628).

| Variable | Value | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female, n/n, % | 12,711/28,628 | 44.4 |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 71.0 (63.0 to 78.0) | n/a |

| Age group, n/n, % | ||

| <65 years | 8517/28,628 | 29.8 |

| 65–74 years | 9323/28,628 | 32.6 |

| ≥75 years | 10,788/28,628 | 37.7 |

| Race, n/n, % | ||

| Afro-Caribbean | 53/28,628 | 0.2 |

| Asian (not Chinese) | 5621/28,628 | 19.6 |

| Chinese | 1541/28,628 | 5.4 |

| Caucasian | 18,199/28,628 | 63.6 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2032/28,628 | 7.1 |

| Mixed/other | 407/28,628 | 1.4 |

| Unwilling to declare/not recorded | 775/28,628 | 2.7 |

| Body mass index, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 27.0 (24.0 to 31.0) | n/a |

| Pulse, median (IQR), bpm | 84.0 (70.0 to 105.0) | n/a |

| Systolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | 131.0 (120.0 to 145.0) | n/a |

| Diastolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | 80.0 (70.0 to 89.0) | n/a |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, n/n (%) | 1665/16,379 | 10.2 |

| Type of atrial fibrillation, n/n (%) | ||

| Permanent | 3638/28,626 | 12.7 |

| Persistent | 4367/28,626 | 15.3 |

| Paroxysmal | 7681/28,626 | 26.8 |

| New onset (unclassified) | 12,940/28,626 | 45.2 |

| Medical history, n/n (%) | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 3532/17,158 | 20.6 |

| Coronary artery disease | 3418/17,158 | 19.9 |

| Acute coronary syndromes | 1613/17,155 | 9.4 |

| Carotid occlusive disease | 867/28,425 | 3.1 |

| Pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis | 768/28,535 | 2.7 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 854/28,067 | 3.0 |

| Stroke/transient ischaemic attack | 3424/28,626 | 12.0 |

| Systemic embolism | 194/28,537 | 0.7 |

| History of bleeding | 780/28,553 | 2.7 |

| History of hypertension | 22,161/28,583 | 77.5 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 11,514/28,080 | 41.0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6211/28,626 | 21.7 |

| Cirrhosis | 154/28,350 | 0.5 |

| Chronic renal disease, n/n (%) | ||

| None or mild (Grades I and II) | 25,655/28,625 | 89.6 |

| Moderate to severe (Grades III to V) | 2970/28,625 | 10.4 |

| Dementia | 410/28,514 | 1.4 |

| Alcohol consumption, n/n (%) | ||

| Abstinent/light | 21,278/24,218 | 87.9 |

| Moderate | 2335/24,218 | 9.6 |

| Heavy | 605/24,218 | 2.5 |

| Current/previous smoker, n/n (%) | 9062/26,046 | 34.8 |

| Antithrombotic treatment, n/n (%) | ||

| Vitamin K antagonists | 9947/28,221 | 35.2 |

| Vitamin K antagonists + antiplatelet | 3127/28,221 | 11.1 |

| Factor Xa inhibitors | 2300/28,221 | 8.1 |

| Factor Xa inhibitors + antiplatelet | 643/28,221 | 2.3 |

| Direct thrombin inhibitors | 1499/28,221 | 5.3 |

| Direct thrombin inhibitors + antiplatelet | 356/28,221 | 1.3 |

| Antiplatelet only | 6905/28,221 | 24.5 |

| None | 3444/28,221 | 12.2 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0 to 4.0) | n/a |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score categories, n/n (%) | ||

| 0 | 687/27,973 | 2.5 |

| 1 | 3352/27,973 | 12.0 |

| 2 | 5539/27,973 | 19.8 |

| 3 | 6753/27,973 | 24.1 |

| 4 | 6165/27,973 | 22.0 |

| 5 | 3255/27,973 | 11.6 |

| 6–9 | 2222/27,973 | 7.9 |

| HAS-BLED score, median (IQR)* | 1.5 (0.9) | n/a |

| HAS-BLED score categories, n/n (%)* | ||

| 0 | 2494/19,402 | 12.9 |

| 1 | 7998/19,402 | 41.2 |

| 2 | 6483/19,402 | 33.4 |

| 3 | 2054/19,402 | 10.6 |

| 4 | 338/19,402 | 1.7 |

| 5 | 34/19,402 | 0.2 |

| 6–9 | 1/19,402 | 0.0 |

| Care setting specialty at diagnosis, n/n (%) | ||

| Cardiology | 18,217/28,626 | 63.6 |

| Geriatrics | 117/28,626 | 0.4 |

| Internal medicine | 5287/28,626 | 18.5 |

| Neurology | 568/28,626 | 2.0 |

| Primary care/general practice | 4437/28,626 | 15.5 |

CHA2DS2-VASc, cardiac failure, hypertension, age ≥75 (doubled), diabetes, stroke (doubled)-vascular disease, age 65–74, and sex category (female); IQR, interquartile range.

*‘modified’ HAS-BLED, hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function (1 point each), stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, elderly (>65), drugs/alcohol concomitantly (1 point each).

Baseline therapies

In patients with CHF, the rates of prescription of guideline-recommended therapies were no drug in 11.7%, one drug in 25.1%, two drugs in 33.6%, three drugs in 23.3%, and four drugs in 6.4% of patients (Table 2). These figures were not affected by the heart failure stage (New York Heart Association I–II vs III–IV).

Table 2. Baseline prescription of guideline-recommended therapies in patients with congestive heart failure or vascular disease*.

| Number of guideline-recommended drugs, n (%) | Patients with congestive heart failure | Patients with vascular disease |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 781 (11.7) | 248 (6.0) |

| 1 | 1675 (25.1) | 708 (17.0) |

| 2 | 2243 (33.6) | 1205 (28.9) |

| 3 | 1556 (23.3) | 1320 (31.7) |

| 4 | 424 (6.4) | 685 (16.4) |

| Total | 6679 (100) | 4166 (100) |

*Guideline-recommended therapies for congestive heart failure: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), betablockers, aldosterone blockade, and loop diuretics; guideline-recommended therapies for vascular disease: aspirin, statins, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, and betablockers.

In patients with VascD, the rates of prescription of guideline-recommended therapies were no drug in 6.0%, one drug in 17.0%, two drugs in 28.9%, three drugs in 31.7%, and four drugs in 16.4% (Table 2).

Details about guideline-recommended drugs for both CHF and VascD are in Table 3.

Table 3. Monotherapy and combinations of guideline-recommended therapies prescribed for patients with congestive heart failure or vascular disease.

| Guideline-recommended therapies | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Congestive heart failure | |

| 1 drug | |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 757 (12.8) |

| BB | 441 (7.5) |

| Aldosterone blockade | 51 (0.9) |

| Loop diuretic | 426 (7.2) |

| 2 drugs | |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB + BB | 707 (12.0) |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB + aldosterone blockade | 106 (1.8) |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB + loop diuretic | 976 (16.5) |

| BB + aldosterone blockade | 33 (0.6) |

| BB + loop diuretic | 318 (5.4) |

| Aldosterone blockade + loop diuretic | 103 (1.8) |

| 3 drugs | |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB + BB + aldosterone blockade | 119 (2.0) |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB + BB + loop diuretic | 1046 (17.7) |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB + aldosterone blockade + loop diuretic | 295 (5.0) |

| BB + aldosterone blockade + loop diuretic | 96 (1.6) |

| 4 drugs | |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB + BB + aldosterone blockade + loop diuretic | 424 (7.2) |

| Vascular disease | |

| 1 drug | |

| ASA | 123 (3.0) |

| BB | 116 (3.0) |

| Statin | 197 (5.0) |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 272 (6.9) |

| 2 drugs | |

| ASA + BB | 91 (2.3) |

| ASA + statin | 261 (6.7) |

| ASA + ACE inhibitor/ARB | 175 (4.5) |

| BB + statin | 132 (3.4) |

| BB + ACE inhibitor/ARB | 166 (4.2) |

| Statin + ACE inhibitor/ARB | 380 (9.7) |

| 3 drugs | |

| ASA + BB + statin | 234 (6.0) |

| ASA + BB + ACE inhibitor/ARB | 135 (3.4) |

| ASA + statin + ACE inhibitor/ARB | 521 (13.3) |

| BB + statin + ACE inhibitor/ARB | 430 (11.0) |

| 4 drugs | |

| ASA + BB + statin + ACE inhibitor/ARB | 685 (17.5) |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA, aspirin; BB, betablocker.

Of the patients with CKD, 36.1% were prescribed ACE inhibitors/ARBs, drugs that may slow the rate of kidney function deterioration.

Clinical outcomes

During 2-year follow-up, the rates (95% CI) of all-cause mortality, stroke/SE, and major bleeding (first occurrences) were 3.84 (3.68; 4.02), 1.27 (1.18; 1.38), and 0.71 (0.64, 0.79) per 100 person-years, respectively (Table 4). Cardiovascular death occurred at a rate of 1.46 (1.36; 1.57) per 100 person-years and constituted 37.9% of deaths (Tables 4 and 5). Non-cardiovascular death occurred at a rate of 1.44 (1.34; 1.55) per 100-person-years and represented 37.4% of deaths (Tables 4 and 5). The most frequent known causes of death were CHF (12.1% of all deaths) and malignancy (11.1% of all deaths) (Table 5).

Table 4. Two-year event rates including additional outcomes.

| Outcome | N | Events | % | Event rate (per 100 person-years) |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause death | 28,628 | 1985 | 6.9 | 3.84 | 3.68; 4.02 |

| Cardiovascular death | 28,628 | 753 | 2.6 | 1.46 | 1.36; 1.57 |

| Non-cardiovascular death | 28,628 | 743 | 2.6 | 1.44 | 1.34; 1.55 |

| Undetermined cause of death | 28,628 | 489 | 1.7 | 0.95 | 0.87; 1.04 |

| Stroke/SE | 28,628 | 651 | 2.3 | 1.27 | 1.18; 1.38 |

| Major bleed | 28,628 | 366 | 1.3 | 0.71 | 0.64; 0.79 |

| MI/ACS | 28,628 | 348 | 1.2 | 0.68 | 0.61; 0.75 |

| Congestive heart failure | 28,628 | 988 | 3.5 | 1.96 | 1.84; 2.08 |

ACS, acute coronary syndromes; CI, confidence interval; MI, myocardial infarction; SE, systemic embolism.

Table 5. Breakdown of primary outcomes by type of event at 2-year follow-up.

| Event | n (%) |

|---|---|

| All-cause death | 1985 |

| Cardiovascular causes | 753 (37.9) |

| Congestive heart failure | 240 (12.1) |

| Sudden/unwitnessed death | 129 (6.5) |

| Acute coronary syndromes | 82 (4.1) |

| Ischaemic stroke | 88 (4.4) |

| Other | 214 (10.8) |

| Non-cardiovascular causes | 743 (37.4) |

| Malignancy | 220 (11.1) |

| Respiratory failure | 150 (7.6) |

| Infection/sepsis | 147 (7.4) |

| Renal | 49 (2.5) |

| Suicide | 1 (0.1) |

| Other | 176 (8.9) |

| Undetermined causes | 489 (24.6) |

| Stroke (not including systemic embolism)* | 625 |

| Primary ischaemic stroke | 441 (70.6) |

| Of which secondary haemorrhagic ischaemic stroke | 27 (4.3) |

| Primary intracerebral haemorrhage | 66 (10.6) |

| Intracerebral | 41 (6.6) |

| Subarachnoid | 5 (0.8) |

| Intraventricular | 7 (1.1) |

| Unknown | 13 (2.1) |

| Undetermined | 118 (18.9) |

| Bleeding events (not including minor bleeds)* | 866 |

| Severity of bleed | |

| Non-major clinically relevant | 500 (57.7) |

| Major | 366 (42.3) |

| Fatal | 60 (6.9) |

*Only the first occurrence of each event was taken into account.

Of the strokes occurring during follow-up, 70.6% were primary ischaemic, 10.6% were primary intracerebral haemorrhages, and 18.9% were undetermined (Table 5). Bleeding events were more likely to be non-major clinically relevant (57.7%) than major (42.3%), and a minority were fatal (6.9%; Table 5).

The rates (95% CI) of myocardial infarction/ACS and of new onset or worsening of CHF during follow-up were 0.68 (0.61; 0.75) and 1.96 (1.84; 2.08) per 100 person-years, respectively (Table 4).

Factors influencing outcomes

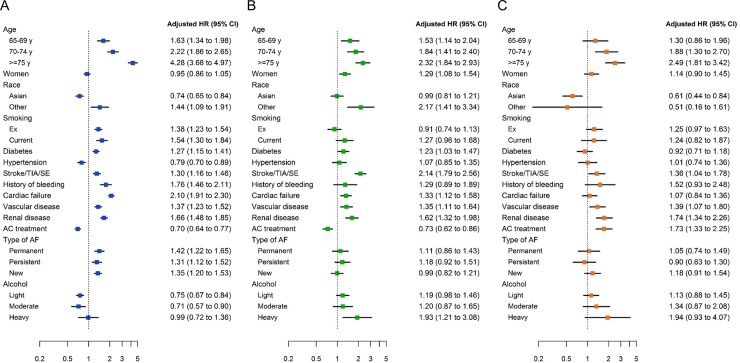

After adjustment, the following baseline variables were found to be significantly associated with a higher risk of death: age, ‘other race’ (vs Caucasian/Hispanic/Latino), smoking, diabetes mellitus, history of stroke/TIA/SE, history of bleeding, cardiac failure, VascD, moderate-to-severe renal disease, and non-paroxysmal forms of AF (Fig 1A). The variables associated with a higher risk of stroke/SE were: age, female sex, ‘other race’ (vs Caucasian/Hispanic/Latino), history of stroke/TIA/SE, CHF, VascD, moderate-to-severe renal disease, and heavy alcohol consumption (Fig 1B). Age, VascD, moderate-to-severe renal disease, and AC treatment were independently associated with a higher risk of major bleeding (Fig 1C). In addition, we observed a trend of increased risk of major bleeding with increasing alcohol consumption (p<0.0001), and a substantial but not statistically significant increase in bleeding risk with previous or current smoking.

Fig 1.

Adjusted hazard ratios for 2-year outcomes according to baseline characteristics and anticoagulant treatment: (A) all-cause mortality; (B) stroke/systemic embolism; (C) major bleeding. ‘Anticoagulant treatment’ includes both vitamin K antagonists and non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. For race, ‘Asian’ includes Asian (not Chinese) and Chinese, and ‘other’ includes Afro-Caribbean, mixed/other, and unwilling to declare/not recorded. Reference groups, from top: <65 years, men, Caucasian/Hispanic/Latino, never smoker, no history of disease (for diabetes, hypertension, stroke/TIA/SE, history of bleeding, cardiac failure, vascular disease, and renal disease), no AC treatment, paroxysmal AF, alcohol abstinence. Hazard ratios were adjusted for all variables in the model. AC, anticoagulant; AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SE, systemic embolism; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Asians had significantly lower risks of death and major bleeding compared with Caucasian/Hispanic/Latino patients, but they also had a lower rate of comorbidities, particularly CKD (7.5% vs 11.09%, p<0.0001), and a significantly lower age (median [IQR] 69 [60–70] vs 72 [64–79]; p<0.0001). AC treatment was associated with lower risks of death and stroke/SE and a higher risk of major bleeding. History of hypertension and pattern of AF were not associated with a higher risk of stroke/SE.

The rates of death, stroke/SE, and major bleeding increased progressively with increasing grades of the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring scheme (Table 6).

Table 6. Crude event rates during 2-year follow-up according to CHA2DS2-VASc score.

| Event | CHA2DS2-VASc 0–1 (n = 4694) |

CHA2DS2-VASc 2 (n = 5539) |

CHA2DS2-VASc 3 (n = 6753) |

CHA2DS2-VASc 4+ (n = 11,642) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke/SE | ||||

| n (%) | 44 (0.9) | 76 (1.4) | 136 (2.0) | 395 (3.4) |

| Rate per 100 person-years (95% CI) | 0.52 (0.38; 0.69) | 0.75 (0.60; 0.94) | 1.11 (0.94; 1.32) | 1.95 (1.77; 2.15) |

| Major bleeding | ||||

| n (%) | 26 (0.6) | 52 (0.9) | 85 (1.3) | 203 (1.7) |

| Rate per 100 person-years (95% CI) | 0.30 (0.21; 0.45) | 0.51 (0.39; 0.67) | 0.69 (0.56; 0.86) | 1.00 (0.87; 1.14) |

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| n (%) | 123 (2.6) | 208 (3.8) | 391 (5.8) | 1263 (10.8) |

| Rate per 100 person-years (95% CI) | 1.44 (1.20; 1.71) | 2.05 (1.79; 2.34) | 3.17 (2.87; 3.50) | 6.14 (5.81; 6.49) |

CHA2DS2-VASc, cardiac failure, hypertension, age ≥75 (doubled), diabetes, stroke (doubled)-vascular disease, age 65–74, and sex category (female); CI, confidence interval; SE, systemic embolism.

Discussion

Many reports have identified the variables associated with outcomes in AF, both in terms of stroke/SE and bleeding, but less frequently death and its causes [12–16]. This study is novel in addressing the variables that influence the risks of all three major outcome measures in a large, global, prospective registry of newly diagnosed AF. It confirms prior observations from a report based on a smaller cohort of the GARFIELD-AF registry with similar baseline characteristics and follow-up. We found that death was the most frequent adverse event, occurring at threefold the rate of stroke/SE and fivefold the rate of major bleeding [3]. Cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular causes of death occurred at a similar rate. Stroke accounted for less than 5% of all deaths. The most frequent causes of death were CHF, sudden death, ACS, malignancy, respiratory failure, and sepsis. Newly diagnosed AF appears to be both a marker of unfavourable outcome linked to underlying comorbidities and a worsening factor of some comorbidities such as CHF, ACS, and respiratory failure, which might be affected by the haemodynamic alterations and the embolic complications linked to AF [3, 17].

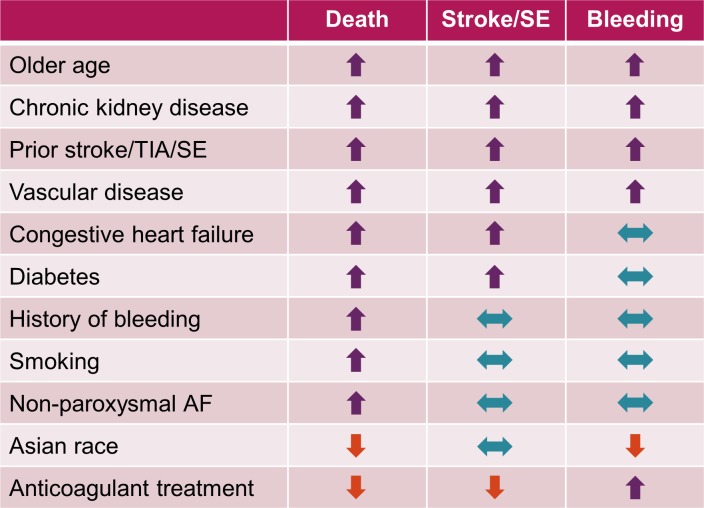

The relationships between different variables and the risks of all-cause mortality, stroke/SE, and major bleeding are summarised in Fig 2. Four variables were associated with higher risks of all three major outcome measures, namely older age, history of stroke/TIA, VascD, and CKD. The first three variables are established predictors of stroke, and are components of the most widely used risk assessment scheme CHA2DS2-VASc. Though CKD is not a component of the CHA2DS2-VASc score, it has a strong influence on the risks of stroke/SE, bleeding, and death [12, 14, 16, 18–20]. CHF, also a component of CHA2DS2-VASc, was associated with higher risks of both death and stroke/SE. Two variables were associated with a higher risk of death only, namely smoking and history of bleeding.

Fig 2. Relationships between variables and clinical outcomes during 2-year follow-up.

Key to symbols used: upwards arrow indicates increased risk, downwards arrow indicates reduced risk, double-headed arrow indicates no change in risk. AF, atrial fibrillation; SE, systemic embolism; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Non-paroxysmal forms of AF were also associated with a higher risk of death, but not of stroke/SE compared with paroxysmal AF. In previous reports from randomised controlled trials and registries, non-paroxysmal forms of AF were consistently reported to be associated with a higher risk of death, but with various findings as regards the risk of stroke/SE [13, 21–24]. Diabetes was also associated with a higher risk of death but was only marginally associated with a higher risk of stroke/SE. Adequate blood glucose balance, shown to prevent the occurrence of microvascular complications and to a lesser extent cardiovascular complications, may explain the lack of association of diabetes with the risk of stroke/SE [25, 26].

Some variables considered to be risk factors were only marginally associated with the risk of events or had a neutral effect, for example, history of hypertension. One may assume that history of hypertension as reported by the investigators in over 70% of the population implies that adequate control of blood pressure was achieved in these patients. We may hypothesise that this may have prevented remodelling of the heart chambers. Interestingly, 7.5% of patients included in GARFIELD-AF had uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure >160 mmHg). This subset of patients had a higher risk of stroke/SE but not of death or bleeding compared to patients without high blood pressure (HR 1.73, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.18).

AC was associated with substantially lower risks of all-cause death (30% lower risk in AC patients compared with non-AC patients) and stroke/SE (28% lower risk in patients receiving AC compared with those not receiving AC), and with a 52% higher risk of bleeding compared with no AC treatment. Reduction in mortality in association with anticoagulation may have been due, in part, to prevention of thromboembolism in patients with CHF, sepsis, respiratory failure, or cancer [3].

In contrast, Asian race was associated with lower risks of death and bleeding, without an excess of stroke/SE compared with non-Asian races. Conflicting observations were previously reported on this issue with the risks of death, stroke/SE, and bleeding found to be identical or higher in Asians compared to non-Asians [27, 28]. In this report, these observations may be due to confounding factors despite adjustment, as these patients were at lower risk than non-Asian patients, as shown by their younger median age, lower rate of comorbidities, particularly CKD, and lower CHA2DS2-VASc score. In addition, in some Asian countries, physicians routinely target a lower INR than in other regions, resulting in a significantly lower risk of bleeding compared with non-Asian patients, yet with no excess risk of stroke/SE [29, 30].

Overall, two messages arise from this report. Firstly, several variables are linked to the risk of one or more outcome measures. So far, the therapeutic approach recommended for the management of AF emphasises rhythm and/or rate control and anticoagulation administered in at-risk patients without contraindication. The decision for treatment is based on clinical judgment and assessment of the risks of stroke/SE and bleeding using clinical risk scores, most commonly CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED. Biomarker-based scores like the recently described ABC score [31] cannot be used in a non-interventional registry, as blood sampling is an intervention. In addition, this approach does not consider the most important risk for patients with AF, namely the risk of death. Therefore, the tools used to assess risks need to be revisited as many variables shown to have an impact on outcome are not included in the commonly used risk scores, and because the risk of death is not considered. For that reason, a new scoring system addressing the risks of all three major outcome measures at once, namely death, stroke/SE and bleeding, derived from a larger cohort may prove useful for clinicians. Such a tool is under development using a larger GARFIELD-AF population as derivation cohort and will be tested on an external validation cohort.

Secondly, this study shows that the comorbidities that strongly affect outcomes are undertreated in at least one-third of patients with newly diagnosed AF. All comorbidities shown to have an impact on outcomes should be addressed. In this regard, aggressive management of CHF, CKD, and VascD and their risk factors, as well as smoking and drinking cessation, should be strongly advocated. Strikingly, patients with comorbidities associated with the risk of two or all three outcome measures, namely CHF, VascD, and CKD, are undertreated if we consider the rates of prescription of guideline-recommended therapies. In patients with CHF, depending on the New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, up to four drugs may be needed [5]. Our data show that irrespective of the NYHA class, at least half of the patients were receiving a maximum of two drugs. In patients with VascD who should receive long term four pharmacological classes, more than half of them were receiving a maximum of two [32]. Undertreatment has commonly been reported in various settings [33–37]. The situation for CKD is more difficult to analyse, as the prescription of ACE/ARB is not unanimously recommended and implemented, and is mostly driven by comorbidities [38, 39]. On the other hand, implementation of guideline-recommended therapies was shown to improve outcomes, particularly in CHF and ACS [40–44]. Whether aggressive management of comorbidities in new-onset AF has a favourable impact on outcomes is not yet known. Only controlled randomised trials comparing strict and lenient management strategies, and to some extent real-life prospective registries such as GARFIELD-AF may help to answer this question.

Study limitations

We focused on three variables only when assessing the prescription rates of guideline-recommended therapies. We cannot assume that our observations are valid for other variables. We did not differentiate between CHF with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. In addition, the collection of data on drug prescriptions in patients with CHF, VascD, and CKD may be suboptimal since GARFIELD-AF is a study on patients with AF, and not specifically on these entities.

Conclusions

Death is the most frequent adverse event in newly diagnosed AF, occurring at threefold the rate of stroke/SE and fivefold the rate of major bleeding. Many modifiable variables have an influence on the risk of one or more major outcome measures, particularly CHF, VascD, and CKD, whose management seems suboptimal as regards the prescription of guideline-recommended drugs in routine practice. Based upon these observations, we advocate for comprehensive management of newly diagnosed AF, particularly the implementation of guideline-recommended therapies in CHF, VascD, and CKD, in addition to anticoagulation. Registries like GARFIELD-AF may help to elucidate the causes of under treatment and to assess the impact on outcomes of aggressive management of the most influential comorbidities.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians, nurses, and patients involved in the GARFIELD-AF registry. We would like to acknowledge the support of investigators from all 1554 sites and the work of the following national coordinators on the GARFIELD-AF registry: Hector Lucas Luciardi (Argentina), Harry Gibbs (Australia), Marianne Brodmann (Austria), Frank Cools (Belgium), Antonio Carlos Pereira Barretto (Brazil), Stuart J. Connolly, Alex Spyropoulos, John Eikelboom (Canada), Ramon Corbalan (Chile), Dayi Hu (China), Petr Jansky (Czech Republic), Jørn Dalsgaard Nielsen (Denmark), Hany Ragy (Egypt), Pekka Raatikainen (Finland), Jean-Yves Le Heuzey (France), Harald Darius (Germany), Matyas Keltai (Hungary), Sanjay Kakkar and Jitendra Pal Singh Sawhney (India), Giancarlo Agnelli and Giuseppe Ambrosio (Italy), Yukihiro Koretsune (Japan), Carlos Jerjes Sánchez Díaz (Mexico), Hugo Ten Cate (the Netherlands), Dan Atar (Norway), Janina Stepinska (Poland), Elizaveta Panchenko (Russia), Toon Wei Lim (Singapore), Barry Jacobson (South Africa), Seil Oh (South Korea), Xavier Viñolas (Spain), Marten Rosenqvist (Sweden), Jan Steffel (Switzerland), Pantep Angchaisuksiri (Thailand), Ali Oto (Turkey), Alex Parkhomenko (Ukraine), Wael Al Mahmeed (United Arab Emirates), David Fitzmaurice (UK), Samuel Z. Goldhaber (USA).SAS programming support was provided by Jagan Allu (TRI, London, UK). Editorial support was provided by Emily Chu (TRI, London, UK).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by an unrestricted research grant from Bayer AG, Berlin, Germany (http://pharma.bayer.com) to the Thrombosis Research Institute, London, UK (A.K.K.), which sponsors the GARFIELD-AF registry. Martin van Eickels is employed by Bayer AG and is a non-voting member of the GARFIELDAF Steering Committee. Bayer AG provided support in the form of salary for author M.v.E., but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific role of this author is articulated in the ‘author contributions’ section.

References

- 1.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr., et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071–104. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893–962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassand JP, Accetta G, Camm AJ, Cools F, Fitzmaurice DA, Fox KA, et al. Two-year outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation: results from GARFIELD-AF. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2882–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts): Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(11):Np1–np96. doi: 10.1177/2047487316653709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(27):2129–200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens PE, Levin A. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11):825–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kakkar AK, Mueller I, Bassand JP, Fitzmaurice DA, Goldhaber SZ, Goto S, et al. Risk profiles and antithrombotic treatment of patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation at risk of stroke: perspectives from the international, observational, prospective GARFIELD registry. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63479 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kakkar AK, Mueller I, Bassand JP, Fitzmaurice DA, Goldhaber SZ, Goto S, et al. International longitudinal registry of patients with atrial fibrillation at risk of stroke: Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD (GARFIELD). Am Heart J. 2012;163(1):13–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox KAA, Gersh BJ, Traore S, Camm AJ, Kayani G, Krogh A, et al. Evolving quality standards for large-scale registries: the GARFIELD-AF experience. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2017;3:114–22. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcw058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res. 2007;16(3):219–42. doi: 10.1177/0962280206074463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey Methodology. 2001;85(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersson T, Magnuson A, Bryngelsson IL, Frobert O, Henriksson KM, Edvardsson N, et al. All-cause mortality in 272,186 patients hospitalized with incident atrial fibrillation 1995–2008: a Swedish nationwide long-term case-control study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(14):1061–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boriani G, Laroche C, Diemberger I, Fantecchi E, Popescu MI, Rasmussen LH, et al. 'Real-world' management and outcomes of patients with paroxysmal vs. non-paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in Europe: the EURObservational Research Programme-Atrial Fibrillation (EORP-AF) General Pilot Registry. Europace. 2016;18(5):648–57. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fauchier L, Samson A, Chaize G, Gaudin AF, Vainchtock A, Bailly C, et al. Cause of death in patients with atrial fibrillation admitted to French hospitals in 2012: a nationwide database study. Open Heart. 2015;2(1):e000290 doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massera D, Wang D, Vorchheimer DA, Negassa A, Garcia MJ. Increased risk of stroke and mortality following new-onset atrial fibrillation during hospitalization. Europace: European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology: journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2017;19(6):929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pokorney SD, Piccini JP, Stevens SR, Patel MR, Pieper KS, Halperin JL, et al. Cause of death and predictors of all-cause mortality in anticoagulated patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: data from ROCKET AF. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(3):e002197 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, Leip EP, Wolf PA, et al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2920–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonso A, Lopez FL, Matsushita K, Loehr LR, Agarwal SK, Chen LY, et al. Chronic kidney disease is associated with the incidence of atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2011;123(25):2946–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.020982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Brien EC, Holmes DN, Ansell JE, Allen LA, Hylek E, Kowey PR, et al. Physician practices regarding contraindications to oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation: findings from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) registry. Am Heart J. 2014;167(4):601–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olesen JB, Lip GY, Kamper AL, Hommel K, Kober L, Lane DA, et al. Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(7):625–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiang CE, Naditch-Brule L, Murin J, Goethals M, Inoue H, O'Neill J, et al. Distribution and risk profile of paroxysmal, persistent, and permanent atrial fibrillation in routine clinical practice: insight from the real-life global survey evaluating patients with atrial fibrillation international registry. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5(4):632–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.970749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friberg L, Hammar N, Rosenqvist M. Stroke in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: report from the Stockholm Cohort of Atrial Fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(8):967–75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Link MS, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Scirica BM, Huikuri H, Oto A, et al. Stroke and mortality risk in patients with various patterns of atrial fibrillation: results from the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial (Effective Anticoagulation With Factor Xa Next Generation in Atrial Fibrillation-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 48). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nieuwlaat R, Dinh T, Olsson SB, Camm AJ, Capucci A, Tieleman RG, et al. Should we abandon the common practice of withholding oral anticoagulation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation? Eur Heart J. 2008;29(7):915–22. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1577–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, Woodward M, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2560–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senoo K, An Y, Ogawa H, Lane DA, Wolff A, Shantsila E, et al. Stroke and death in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation in Japan compared with the United Kingdom. Heart. 2016;102(23):1878–82. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathur R, Pollara E, Hull S, Schofield P, Ashworth M, Robson J. Ethnicity and stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart. 2013;99(15):1087–92. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atarashi H, Inoue H, Okumura K, Yamashita T, Kumagai N, Origasa H, et al. Present status of anticoagulation treatment in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the J-RHYTHM Registry. Circ J. 2011;75(6):1328–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue H. Thromboembolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: comparison between Asian and Western countries. J Cardiol. 2013;61(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2012.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hijazi Z, Lindback J, Alexander JH, Hanna M, Held C, Hylek EM, et al. The ABC (age, biomarkers, clinical history) stroke risk score: a biomarker-based risk score for predicting stroke in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(20):1582–90. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(3):267–315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner GM, Calvert M, Feltham MG, Ryan R, Fitzmaurice D, Cheng KK, et al. Under-prescribing of prevention drugs and primary prevention of stroke and transient ischaemic attack in UK general practice: a retrospective analysis. PLoS Med. 2016;13(11):e1002169 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen DC, Armstrong EJ, Singh GD, Amsterdam EA, Laird JR. Adherence to guideline-recommended therapies among patients with diverse manifestations of vascular disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:185–92. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S76651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allen NB, Kaltenbach L, Goldstein LB, Olson DM, Smith EE, Peterson ED, et al. Regional variation in recommended treatments for ischemic stroke and TIA: Get with the Guidelines—Stroke 2003–2010. Stroke. 2012;43(7):1858–64. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.652305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heras M, Bueno H, Bardaji A, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Marti H, Marrugat J. Magnitude and consequences of undertreatment of high-risk patients with non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from the DESCARTES Registry. Heart. 2006;92(11):1571–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.079673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puymirat E, Caudron J, Steg PG, Lemesle G, Cottin Y, Coste P, et al. Prognostic impact of non-compliance with guidelines-recommended times to reperfusion therapy in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. The FAST-MI 2010 registry. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2017;6(1):26–33. doi: 10.1177/2048872615610893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Estrella MM, Jaar BG, Cavanaugh KL, Fox CH, Perazella MA, Soman SS, et al. Perceptions and use of the national kidney foundation KDOQI guidelines: a survey of U.S. renal healthcare providers. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:230 doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Philipneri MD, Rocca Rey LA, Schnitzler MA, Abbott KC, Brennan DC, Takemoto SK, et al. Delivery patterns of recommended chronic kidney disease care in clinical practice: administrative claims-based analysis and systematic literature review. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2008;12(1):41–52. doi: 10.1007/s10157-007-0016-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Curtis AB, Gheorghiade M, Liu Y, Mehra MR, et al. Incremental reduction in risk of death associated with use of guideline-recommended therapies in patients with heart failure: a nested case-control analysis of IMPROVE HF. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1(1):16–26. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehta RH, Chen AY, Alexander KP, Ohman EM, Roe MT, Peterson ED. Doing the right things and doing them the right way: association between hospital guideline adherence, dosing safety, and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2015;131(11):980–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong EJ, Chen DC, Westin GG, Singh S, McCoach CE, Bang H, et al. Adherence to guideline-recommended therapy is associated with decreased major adverse cardiovascular events and major adverse limb events among patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(2):e000697 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, Schramm TK, Hansen ML, Buch P, et al. Persistent use of evidence-based pharmacotherapy in heart failure is associated with improved outcomes. Circulation. 2007;116(7):737–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Putera M, Roark R, Lopes RD, Udayakumar K, Peterson ED, Califf RM, et al. Translation of acute coronary syndrome therapies: from evidence to routine clinical practice. Am Heart J. 2015;169(2):266–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.