Abstract

Objective:

To determine the influence of the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs4245739 on the binding and expression of microRNAs and subsequent MDM4 expression and the correlation of these factors with clinical determinants of ER-negative breast cancers.

Methods:

FindTar and miRanda were used to detect the manner in which potential microRNAs are affected by the SNP rs4245739-flanking sequence. RNA sequencing data for ER-negative breast cancer from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were used to compare the expression of miR-184, miR-191, miR-193a, miR-378, and MDM4 in different rs4245739 genotypes.

Results:

Comparison of ER-negative cancer patients with and without the expression of miR-191 as well as profile microRNAs (miR-184, miR-191, miR-193a and miR-378 altogether) can differentiate the expression of MDM4 among different rs4245739 genotypes. Although simple genotyping alone did not reveal significant clinical relationships, the combination of genotyping and microRNA profiles was able to significantly differentiate individuals with larger tumor size and lower number of involved lymph nodes (P < 0.05) in the risk group (A allele).

Conclusions:

We present two novel methods to analyze SNPs within 3′UTRs that use: (i) a single miRNA marker expression and (ii) an expression profile of miRNAs predicted to bind to the SNP region. We demonstrate that the application of these two methods, in particular the miRNA profile approach, permits detection of new molecular and clinical features related to the rs4245739 variant in ER-negative breast cancer.

Keywords: Rs4245739, ER-negative breast cancer, MDM4, microRNA, clinical relevance

Introduction

Genetic variations, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), have emerged as an important resource in the understanding of carcinogenesis1-3. Recently, several studies have reported the role of SNPs in carcinogenesis through their associations with the binding and expression of microRNA (miRNAs)4-6. MiRNAs are short non-coding RNAs (~18–25 nucleotides) that negatively regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by directly binding to mRNA targets7,8. MiRNAs have been associated with the pathogenesis of almost every human cancer through regulation of several important biological pathways, including cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis8-11. Unique patterns of miRNA expression have been proposed as clinical biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets in several cancers12-15.

One SNP, rs4245739, has been identified as a risk factor for several cancers, including esophageal cancer16, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma17, prostate cancer18, lung cancer19, and ovarian cancer20. Rs4245739(A > C) has also been associated with susceptibility to breast cancer 21, the most common cancer among women and the fifth leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide22,23. In a study involving a total of more than 10,000 breast cancers negative for estrogen receptor (ER) expression and 75,000 control cases from patients of Caucasian ancestry, pooled results showed that rs4245739 was associated with the risk of ER-negative breast cancer (P < 0.01) but not the risk of ER-positive breast cancer, with an odds ratio (OR) for the A risk allele of 1.14 (95% CI = 1.10–1.18) 22. Subsequent studies from China (1,100 breast cancer cases/1,400 controls) and Norway (1,717 breast cancer patients/1,870 controls) have also documented rs4245739 as a risk variant for breast cancer21,24.

Rs4245739(A > C) is located in the three prime untranslated region (3’UTR) of MDM425, an oncogene that negatively regulates p53 expression by directly binding and masking the transactivation domain in response to DNA damage26. This SNP creates a target binding site for the miRNA miR-191-5p, which has been linked to several cancer types18,25. A functional study revealed miRNA-mediated fine-tuning of MDM4 expression as a result of miR-191-5p binding to the C-allele but not the A-allele of rs424573925. Therefore, in A-allele genotypes, MDM4 is overexpressed and associated with a higher risk of breast cancer25. In ovarian cancer, patients with the AA genotype showed significantly increased risk of recurrence and mortality25. Upregulation of miR-191-5p has been reported in breast cancer, although its specific role in carcinogenesis or progression in this cancer type is not yet known27.

In this study, we used a combination of genetic variant data, in silico prediction, and miRNA expression profiles to demonstrate processes by which molecular mechanisms involved in the SNP located at the 3’UTR of the MDM4 gene can alter the expression of several miRNAs associated with specific clinical features, i.e., tumor size and lymph node infiltration in breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Tumor array and sequencing data

Affymetrix Genome-wide SNP 6.0 microarray (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), gene-level miRNA, and gene-level mRNA sequencing data were retrieved for The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) breast cancer cohort28. RNA sequencing data determined with RNA-Seq by Expectation-Maximization (RSEM) software were used. ER-negativity was determined from immunohistochemical records. Altogether, SNP array and expression data were available for 189 primary ER-negative breast cancers. For these cancers, we were able to find corresponding clinical stage, tumor size, and lymph node status.

SNP survey

SNPs listed on dbSNP were extracted, and those with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of less than 0.1 were removed to yield a total of 11,052,394 SNPs29. The genomic location of SNPs was determined with reference to the human genome assembly GRCh37.

SNP genotyping

Genotypes for the 906,600 SNP probes of the Affymetrix SNP 6.0 platform (Affymetrix, Inc.) were determined by first mapping probe set IDs to dbSNP rs IDs. The R package genomewidesnp6Crlmm was then used for genotype calls, with calls having a confidence level of less than 90% filtered out. All 189 samples were retained for rs4245739.

MiRNA-mRNA binding alteration prediction

We used the algorithms FindTar (http://bio.sz.tsinghua.edu.cn/findtar)30 and miRanda (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do) to predict the mRNA targets of miRNAs.

Bioinformatic and statistical analysis

Bioinformatic and statistical analyses were conducted with the R statistical package version 3.1.2. Cut-offs for the different methods were determined as described previously31. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant unless otherwise stated.

Results

Screen of SNPs located at UTRs and miRNA-mRNA binding alterations due to rs4245739

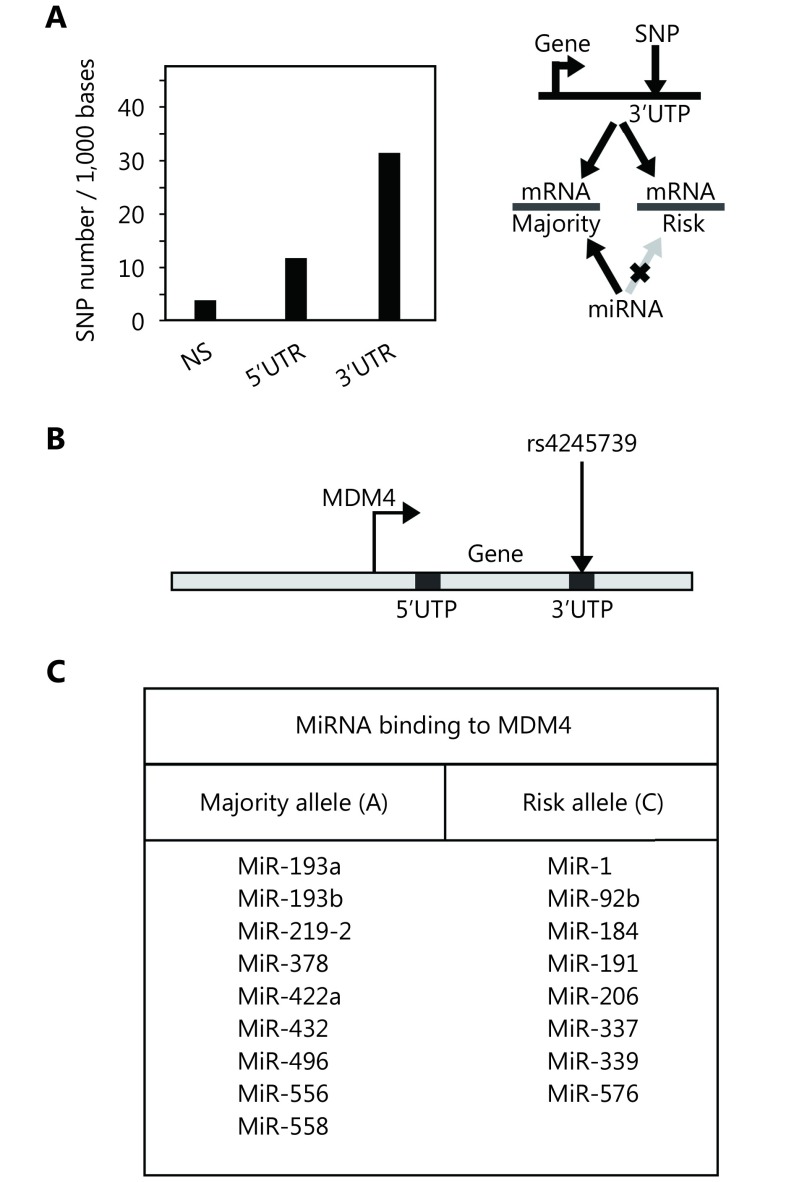

We analyzed the role of SNPs present in the 3’UTRs of the human genome. After discarding those with a MAF of less than 0.1, we obtained 11,052,394 SNPs, the majority of which were inter-genic. Of the SNPs located in genes, more than 100,000 were in 3’UTRs, a quantity almost two and four times the amounts in the coding regions (non-synonymous only) and 5’UTRs, respectively. We next calculated the probability of finding SNPs in these regions calibrated by their total base length in the genome (Figure 1A, left). This probability was higher for 3’UTR regions compared to the coding regions and 5’UTRs, suggesting a selective pressure for this occurrence. We therefore predicted that some of the 3’UTR-located SNPs may alter the binding ability of regulatory miRNAs (Figure 1A, right), which may in turn mediate allele-dependent mRNA post-transcriptional stability. We assessed this phenomenon by analyzing rs4245739, which is present in the 3’UTR of the MDM4 gene and for which the A allele predisposes individuals to ER-negative breast cancer (Figure 1B).22 We used the FindTar330 and miRanda32 algorithms to predict miRNA-mRNA binding alterations between risk and wild type alleles of 3’UTRs produced by rs4245739 (Figure 1C), which showed not only miR-191 but other miRNAs to be affected by this SNP.

1.

MiRNA binding alterations due to SNP rs4245739. (A) Distribution of SNPs located at the 3’UTR and 5’UTR per 100,000 bases in comparison to coding regions (NS) in the human genome (left panel). Schematic description of how SNP located at the 3’UTR might influence binding sites of miRNA (right panel). (B) Schematic representation of SNP rs4245739, which is located at the 3’UTR of the MDM4 gene. (C) Potential binding alterations of several miRNAs due to rs4245739 that affect not only miR-191 but also 16 additional miRNAs.

Expression of miRNAs affected by SNP rs4245739 genotypes in patients with ER-negative breast cancer

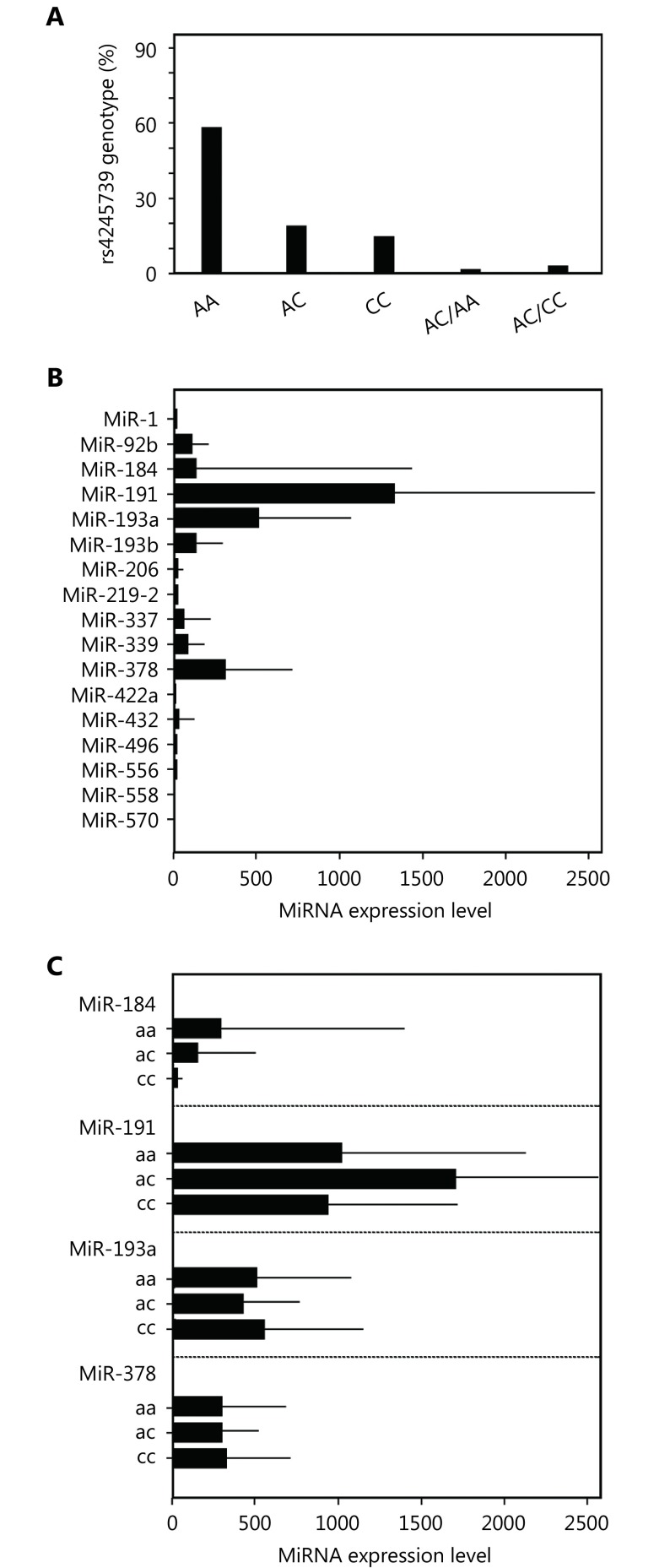

We used an ER-negative breast cancer data set retrieved from the TCGA to study the manner in which the potential alterations in miRNA binding result in phenotypic changes. First, we obtained the rs4245739 genotype of individuals from this data set and observed the homozygotic genotype (CC) and heterozygotic genotype (AC) in approximately 20% of primary tumors (Figure 2A). Interestingly, there were very few genotypic changes between germline and tumor tissue, with only conversion from the heterozygote to either the homozygote C-allele or homozygote A-allele being observed. We next focused on the expression of miRNAs with binding to MDM4 that could be altered in an allele-dependent manner (Figure 2B). Only miR-184, miR-191, miR-193a, and miR-378 had an appreciable average expression, albeit with a large variance. Notably, two of these miRNAs (miR-193a and miR-378) were predicted to bind to the A-allele MDM4 3’UTR only, whereas the other two (miR-184 and miR-191) were predicted to bind to it only in the presence of the C-allele. Examination of whether the expression of these miRNAs differed between genotypes did not yield significant results (Figure 2C).

2.

Expression of miRNAs according to different rs4245739 genotypes in ER-negative breast cancer. (A) Distribution of ER-negative breast cancer patients according to rs4245739 genotypes. (B) Expression of 17 miRNAs with binding to MDM4 mRNAs that is altered owing to rs4245739. (C) Expression of miR-184, miR-191, miR-193a, and miR-378 in different rs4245739 genotypes.

Characterization of rs4245739-affected miRNA expression and 3’UTR SNP functions

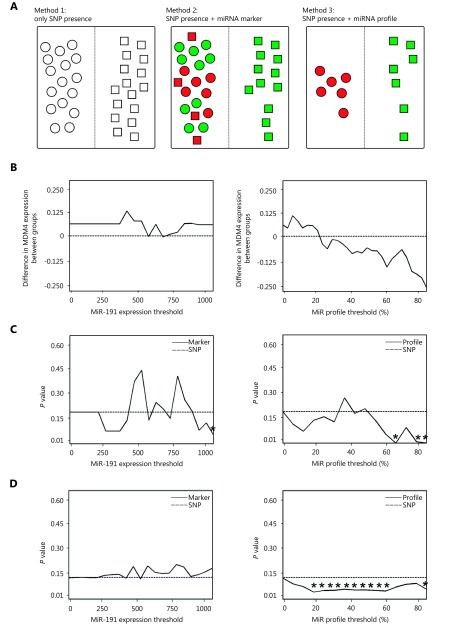

Reasoning that the expression level of these miRNAs may complement our ability to understand 3’UTR SNP function and its effect on disease, we approached the characterization of rs4245739 in three different ways (Figure 3A). In the first approach, we simply grouped tumors according to rs4245739 genotype (Figure 3A, left). In the second method, we additionally stratified patients according to expression or lack of expression of miRNA-191 (Figure 3A, center), which would enable us to assert with more confidence whether allele-dependent miRNA modulation of MDM4 was occurring. Our final approach for classifying samples consisted of generating an miRNA profile of each individual (Figure 3A, right). In the case of rs4245739, we retrieved from the TCGA data sets the expression levels of the four miRNAs predicted to affect MDM4 expression (miR-184, miR-191, miR-193a, and miR-378). Given that miR-193a and miR-378 would bind to the A-allele-containing 3’UTR, and miR-184 and miR-191 would bind to the C-allele-containing 3’UTR, we divided the individuals into an A-allele SNP+/miR-193a-/miR-378- group and a C-allele SNP+/miR-184+/miR-191+ group. These two groups would represent A-genotype individuals without miRNA-mediated MDM4 alterations, and C-genotype individuals with miRNA-mediated MDM4 alterations. We compared these two novel approaches to 3’UTR SNP analysis with the genotype-only classification by performing differential MDM4 gene expression analysis between the groups with each approach. In order to categorize tumors into miR-191-expressing and non-miR-191-expressing cases, we compared the results obtained with different thresholds against the results from the simple genotyping approach (Figure 3B, left). We did not observe significant changes in MDM4 expression among any of the groups generated by simple genotyping or the miR-191-expressing approach. Nevertheless, when we applied the miRNA-profile approach with different miRNA expression thresholds (differences in Figure 3B, right, and P values in Figure S1A, left), we observed significant changes in MDM4 expression. Unexpectedly, we found overexpression of MDM4 in the case of miRNA binding to its 3’UTR. In light of these results, we analyzed the expression of other genes located near (< 2Mb) the rs4245739 SNP using the miRNA profile approach. Three other genes (MFSD4, SLC26A9, and SLC41A1) were significantly repressed in the miRNA-bound groups (Figure S1A, right).

3.

Characterization of rs4245739-affected miRNA expression using several methods to show 3’UTR function.

Activated biological pathways in patients with ER-negative cancer with different rs4245739 genotypes and miRNA expression profiles

We next analyzed the full transcriptome to detect whether gene expression differences were conserved among the different methods. We observed 100% overlap between the sets of differentially expressed genes identified by these two techniques up to a threshold of 300 units of miR-191 expression, at which point the overlap rapidly fell below 50% (Figure S1B, S1C, left). At the same time, the number of genes detected by the marker method remained relatively stable across different expression thresholds (Figure S1B, S1C, right). Finally, when we analyzed the results obtained with the third method, which combined the expression levels of miRNA predicted to bind to a given allele to give an integrated score, we found that the differentially expressed gene overlap between the combined approach and simple genotyping approaches rapidly decreased (Figure 1C, left). As with the previous method comparison, differences were not related to the number of genes obtained with each approach (Figure 1C, right). To analyze the biological importance of the genes obtained, we used the 95th percentile of the entire miRNA expression data set in the case of the miR-191 marker. As a result, we obtained two groups: one comprising individuals with the C-genotype and miR-191 expression above the aforementioned cut-off (n = 37), and another comprising all other individuals (n = 157). In the case of the miRNA profile method, we restricted our samples to the 70% of individuals following the miRNA profile results. The two groups comprised 75 individuals with the A-genotype, and 45 individuals with the C-allele. We performed pathway analysis of these results using the DAVID webserver (Tables 1-3). We found processes such as “immune response” and “cell adhesion” to be overrepresented in all three methods, but each method also detected specific pathways. For example, a protocadherin cluster was found only when using the miRNA profile.

1.

DAVID results for rs4245739 analysis using method 1 (only SNP presence/absence)

| Term | Count | Fold Enrichment | P |

| IL12/Stat4 signaling

pathway in TH1 |

5 | 29.9 | 0.0001 |

| Signal peptide | 38 | 1.8 | 0.0002 |

| Cell activation | 9 | 4.6 | 0.0007 |

| Cell adhesion | 14 | 2.9 | 0.0008 |

| ER | 68 | 1.3 | 0.0031 |

| Immune response | 13 | 2.7 | 0.0024 |

3.

DAVID results for rs4245739 analysis using method 3 (SNP and miR profile)

| Term | Count | Fold Enrichment | P |

| Protocadherin beta | 5 | 33.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Basolateral plasma membrane | 11 | 6 | < 0.0001 |

| Cell adhesion | 15 | 4.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Immune response | 23 | 2.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Spectrin/alpha-actinin | 5 | 18.4 | 0.0001 |

| Integrin binding | 6 | 10.7 | 0.0002 |

| ARVC (cardiomyopathy) | 5 | 8.4 | 0.0026 |

| Epidermolysis bullosa | 3 | 29.0 | 0.0046 |

Clinical relevance of characterization of SNP rs4245739 genotypes and miRNA profiles

Finally, we assessed the strength of association between the results of these new methods and clinical parameters. The use of simple genotyping alone failed to reveal any significant relationships (Figure 3C and D and Figure S2, P values marked by dotted lines). When we examined tumor size categories of samples, we found significant differences among groups using both methods at higher thresholds (P values in Figure 3C, differences in Figure S2A). In addition, the number of lymph nodes affected in individuals was found to be significantly reduced in the C-allele group obtained by the miRNA profile method (P values in Figure 3D, right; differences in Supplementary Figure 2B, right), using several different thresholds. Results with the marker method, similar to those using the simple genotyping approach, did not reach significance in this association (Figure 3D, left; Supplementary Figure 2B, left). Associations with other clinical parameters, including breast cancer mortality (Supplementary Figure 2C) and clinical stage (Supplementary Figure 2D), were not statistically significant. Our novel methods thus improve the prediction of these associations compared to mere use of the presence or absence of a SNP variant.

2.

DAVID results for rs4245739 analysis using method 2 (SNP and miR-191 expression)

| Term | Count | Fold Enrichment | P |

| Immune response | 114 | 1.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Cell adhesion | 24 | 4.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Extracellular matrix | 20 | 4.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Glycoprotein | 86 | 1.6 | < 0.0001 |

| EGF-like domain | 13 | 4.5 | 0.0001 |

| Focal adhesion | 10 | 4.4 | 0.0003 |

| Cell morphogenesis | 14 | 2.9 | 0.0012 |

| Negative regulation of proliferation | 13 | 2.6 | 0.0041 |

| Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases | 3 | 26.6 | 0.0045 |

Discussion

We demonstrated the use of a single miRNA expression marker and expression profile of miRNAs associated with rs4245739, a SNP located at the 3’UTR of the MDM4 gene, to identify tumor features linked to this variant. Our methods, in particular, use of the expression profile, were superior compared to classification based on a single SNP in predicting disease characteristics and outcomes among patients with ER-negative breast cancer. In addition, we found overexpression of MDM4 in the case of miRNA binding to its 3’UTR. Previous research has shown that rs4245739 affects binding of miR-191 and regulates expression of MDM4 mRNA in ovarian cancer25. These findings demonstrate the complexity of the processes governing miRNA-mRNA interactions18,33. We combined SNP genotyping data with miRNA as well as MDM4 expression in ER-negative breast cancer. Single miRNA expression in the presence of the SNP variant did not influence MDM4 expression (Figure 3B, left). However, using the miRNA profile approach, we were able to observe differential changes in MDM4 expression (Figure 3B, right; Figure S1A, left). Our results confirm the findings of a previous study of ovarian cancer by Wynandaele and colleagues25.

More importantly, by combining SNP variant presence and the miRNA profile approach, we were able to differentiate subgroups of patients at risk with greater tumor size and number of lymph nodes infiltrated, indicating the potential for the use of SNPs in this way as diagnostic and prognostic markers in ER-negative breast cancer. Tumor size is used together with nodal and metastasis status to determine clinical breast cancer staging and suitable breast cancer management. In addition, around 30% of breast cancers are ER-negative tumors, with a higher proportion in young breast cancer patients, and these tumors constitute a subgroup with relatively poorer prognosis and fewer treatment options34-36. Our enrichment results showed a common theme of immune response across the three different methods; these findings that are consistent with previous results highlighting the importance of immune pathways in ER-negative breast cancer37-39.

We found differential MDM4 expression using microRNA profiles in relation to different genotypes. Our findings support the previous notion that SNPs located at 3’UTRs may lead to dysregulation of target mRNAs and are potentially implicated in the development of cancer and other chronic diseases25. Indeed, many studies have shown that SNP variants in the 3’UTR elevate the risk of developing several cancer types. Saetrom and associates40 showed that rs1434536 located at the bone morphogenetic receptor type 1B gene (BMPR1B) 3’UTR influences the binding of miR-125b and correlates with breast cancer risk. Located at the estrogen receptor-1 gene (ESR1) 3’UTR, rs9341070 is a risk variant for breast cancer. The SNP affects interaction with miR-206 and influences the expression of ESR141. As a risk variant for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, SNP rs8126 (T > C) is located at the TNFAIP2 3’UTR and influences the expression of TNFAIP242. In addition, rs3134615, which is a susceptibility variant for small-cell lung cancer, is located at the MYCL1 3’UTR and influences the affinity for miR-182743. Rs34764978, which is mapped at the 3’UTR of human dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), affects the binding and expression of miR-24 and correlates significantly with resistance to the chemotherapeutic agent methotrexate44. These data show that SNPs of specific genes located at the 3’UTR play an important role in the pathogenesis of several diseases through modulating the binding of particular miRNAs.

MiR-19125 as well as miR-184, miR-193, and miR378 interact and modulate MDM4 expression to certain rs4245739 genotypes. MDM4 is an oncogene that inhibits p53 tumor suppressor proteins during regulation of cell proliferation and response to DNA damage25. Nagpal et al27. have reported that miR-191 is an estrogen-sensitive microRNA that acts in regulation of cell proliferation through inhibition of BDNF, CDK6, and SATB1. MiR-184 regulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway during mammary development and tumor progression45 as well as p53/p21 activity during the cell cycle and cell migration46. MiR-193a inhibits cell growth and migration in breast cancer cells by directly targeting NLN, CCND1, PLAU, and SEPN147. MiR-378 induces a metabolic shift from the glycolytic to the oxidative pathway through PGC-1β/ERRγ48, and modulates therapeutic responses to tamoxifen by targeting GOLT1A49. In addition, gene enrichment pathway analysis revealed that biological processes such as “immune response” and “cell adhesion” were overrepresented in all three methods we used, suggesting that these microRNAs play roles in immune response and cell migration. As its binding affinity for the MDM4 3’UTR is affected by SNP rs4245739, miR-92b is an important candidate for further functional studies because the precursor sequence forms a stem loop for miR-17-92 cluster, which plays a significant role in the carcinogenesis of many cancers, including breast cancer50. MiR-17-92 cluster is known as oncomir-150,51. Further investigations could involve experiments to confirm functional rs4245739, miR-92b, and MDM4 or TP53 expression with the use of luciferase reporter assays and overexpression of miR-92 mimics in combination with reverse transcription-PCR in cell lines.

Acknowledgements

Wahyu Wulaningsih was supported by grants from UK Medical Research Councils (Grant No. MC_UU_12019/2 and MC_UU_12019/4). Sumadi Lukman Anwar received a grant from PTUPT (Grant No. Ristekdikti 09_18).

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

References

- 1.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013; 339: 1546-58.

- 2.Manolio TA. Bringing genome-wide association findings into clinical use. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:549–58. doi: 10.1038/nrg3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khurana E, Fu Y, Chakravarty D, Demichelis F, Rubin MA, Gerstein M. Role of non-coding sequence variants in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:93–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan BM, Robles AI, Harris CC. Genetic variation in microRNA networks: the implications for cancer research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrc2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang H, Su YL, Yu H, Qian BY. Meta-analysis of the association between Mir-196a-2 polymorphism and cancer susceptibility. Cancer Biol Med. 2012;9:63–72. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-3941.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gong J, Tong Y, Zhang HM, Wang K, Hu T, Shan G, et al. Genome-wide identification of SNPs in MicroRNA genes and the SNP effects on MicroRNA target binding and biogenesis. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:254–63. doi: 10.1002/humu.21641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ha MJ, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:509–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macfarlane LA, Murphy PR. MicroRNA: biogenesis, function and role in cancer. Curr Genomics. 2010;11:537–61. doi: 10.2174/138920210793175895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:704–14. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lovat F, Valeri N, Croce CM. MicroRNAs in the pathogenesis of cancer. Semin Oncol. 2011;38:724–33. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iorio M V, Croce CM. microRNA involvement in human cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1126–33. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanaihara N, Caplen N, Bowman E, Seike M, Kumamoto K, Yi M, et al. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pal MK, Jaiswar SP, Dwivedi VN, Tripathi AK, Dwivedi A, Sankhwar P. MicroRNA: a new and promising potential biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis of ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12:328–41. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Ippolito E, Iorio MV. MicroRNAs and triple negative breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:22202–20. doi: 10.3390/ijms141122202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anwar SL, Lehmann U. MicroRNAs: emerging novel clinical biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinomas. J Clin Med. 2015;4:1631–50. doi: 10.3390/jcm4081631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou LP, Zhang XJ, Li ZQ, Zhou CC, Li M, Tang XH, et al. Association of a genetic variation in a miR-191 binding site in MDM4 with risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma . PLoS One. 2013;8:e64331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan CB, Wei JY, Yuan CL, Wang X, Jiang CW, Zhou CC, et al. The functional TP53 rs1042522 and MDM4 rs4245739 genetic variants contribute to non-hodgkin lymphoma risk . PLoS One. 2014;9:e107047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stegeman S, Moya L, Selth LA, Spurdle AB, Clements JA, Batra J. A genetic variant of MDM4 influences regulation by multiple microRNAs in prostate cancer . Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22:265–76. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao F, Xiong XY, Pan WT, Yang XY, Zhou CC, Yuan QP, et al. A regulatory MDM4 genetic variant locating in the binding sequence of multiple MicroRNAs contributes to susceptibility of small cell lung cancer . PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gansmo LB, Bjørnslett M, Halle MK, Salvesen HB, Dørum A, Birkeland E, et al. The MDM4 SNP34091 (rs4245739) C-allele is associated with increased risk of ovarian—but not endometrial cancer . Tumor Biol. 2016;37:10697–702. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4940-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gansmo LB, Romundstad P, Birkeland E, Hveem K, Vatten L, Knappskog S, et al. MDM4 SNP34091 (rs4245739) and its effect on breast-, colon-, lung-, and prostate cancer risk . Cancer Med. 2015;4:1901–7. doi: 10.1002/cam4.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Closas M, Couch FJ, Lindstrom S, Michailidou K, Schmidt MK, Brook MN, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify four ER negative-specific breast cancer risk loci. Nat Genet. 2013;45:392–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel R, Ma JM, Zou ZH, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu JB, Tang XH, Li M, Lu C, Shi J, Zhou LQ, et al. Functional MDM4 rs4245739 genetic variant, alone and in combination with P53 Arg72Pro polymorphism, contributes to breast cancer susceptibility . Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140:151–7. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2615-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wynendaele J, Böhnke A, Leucci E, Nielsen SJ, Lambertz I, Hammer S, et al. An illegitimate microRNA target site within the 3′ UTR of MDM4 affects ovarian cancer progression and chemosensitivity . Cancer Res. 2010;70:9641–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mancini F, Di Conza G, Monti O, Macchiarulo A, Pellicciari R, Pontecorvi A, et al. Puzzling over MDM4-p53 network. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1080–3. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagpal N, Ahmad HM, Molparia B, Kulshreshtha R. MicroRNA-191, an estrogen-responsive microRNA, functions as an oncogenic regulator in human breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013; 34: 1889-99.

- 28.Koboldt DC, Fulton RS, McLellan MD, Schmidt H, Kalicki-Veizer J, McMichael JF, et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye WB, Lv Q, Wong CKA, Hu S, Fu C, Hua Z, et al. The effect of central loops in miRNA: MRE duplexes on the efficiency of miRNA-mediated gene regulation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joshi S, Watkins J, Gazinska P, Brown JP, Gillett CE, Grigoriadis A, et al. Digital imaging in the immunohistochemical evaluation of the proliferation markers Ki67, MCM2 and Geminin, in early breast cancer, and their putative prognostic value. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:546.. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1531-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Kouwenhove M, Kedde M, Agami R. MicroRNA regulation by RNA-binding proteins and its implications for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:644–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blows FM, Driver KE, Schmidt MK, Broeks A, van Leeuwen FE, Wesseling J, et al. Subtyping of breast cancer by immunohistochemistry to investigate a relationship between subtype and short and long term survival: A collaborative analysis of data for 10,159 cases from 12 studies. PLoS Med. 2010; 7: e1000279.

- 35.Bagaria SP, Ray PS, Sim MS, Ye X, Shamonki JM, Cui XJ, et al. Personalizing breast cancer staging by the inclusion of ER, PR, and HER2. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:125–9. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wahba HA, El-Hadaad HA. Current approaches in treatment of triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Biol Med. 2015;12:106–16. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2015.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marra P, Mathew S, Grigoriadis A, Wu Y, Kyle-Cezar F, Watkins J, et al. IL15RA drives antagonistic mechanisms of cancer development and immune control in lymphocyte-enriched triple-negative breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4908–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dushyanthen S, Beavis PA, Savas P, Teo ZL, Zhou CH, Mansour M, et al. Relevance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer. BMC Med. 2015; 13: 202.

- 39.Einefors R, Kogler U, Ellberg C, Olsson H. Autoimmune diseases and hypersensitivities improve the prognosis in ER-negative breast cancer. SpringerPlus. 2013;2:357. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sætrom P, Biesinger J, Li SM, Smith D, Thomas LF, Majzoub K, et al. A risk variant in an miR-125b binding site in BMPR1B is associated with breast cancer pathogenesis . Cancer Res. 2009;69:7459–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams BD, Furneaux H, White BA. The micro-ribonucleic acid (miRNA) miR-206 targets the human estrogen receptor-α(ERα) and represses ERα messenger RNA and protein expression in breast cancer cell lines. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1132–47. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu ZS, Wei S, Ma HX, Zhao M, Myers JN, Weber RS, et al. A functional variant at the miR-184 binding site in TNFAIP2 and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck . Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1668–74. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiong F, Wu C, Chang J, Yu DK, Xu BH, Yuan P, et al. Genetic variation in an miRNA-1827 binding site in MYCL1 alters susceptibility to small-cell lung cancer . Cancer Res. 2011;71:5175–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mishra PJ, Humeniuk R, Mishra PJ, Longo-Sorbello GSA, Banerjee D, Bertino JR. A miR-24 microRNA binding-site polymorphism in dihydrofolate reductase gene leads to methotrexate resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13513–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phua YW, Nguyen A, Roden DL, Elsworth B, Deng NT, Nikolic I, et al. MicroRNA profiling of the pubertal mouse mammary gland identifies miR-184 as a candidate breast tumour suppressor gene. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:83. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0593-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng R, Dong L. Inhibitory effect of miR-184 on the potential of proliferation and invasion in human glioma and breast cancer cells in vitro . Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015;8:9376–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai KW, Leung CM, Lo YH, Chen TW, Chan WC, Yu SY, et al. Arm selection preference of MicroRNA-193a varies in breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016; 6: 28176.

- 48.Eichner LJ, Perry MC, Dufour CR, Bertos N, Park M, St-Pierre J, et al. miR-378 mediates metabolic shift in breast cancer cells via the PGC-1β/ERRγ transcriptional pathway. Cell Metab. 2010; 12: 352-61.

- 49.Ikeda K, Horie-Inoue K, Ueno T, Suzuki T, Sato W, Shigekawa T, et al. miR-378a-3p modulates tamoxifen sensitivity in breast cancer MCF-7 cells through targeting GOLT1A. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13170. doi: 10.1038/srep13170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mendell JT. miRiad roles for the miR-17-92 cluster in development and disease. Cell. 2008;133:217–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435:828–33. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]