Abstract

Objective

To study the relationships between the different domains of quality of primary health care for the evaluation of health system performance and for informing policy decision making.

Data Sources

A total of 137 quality indicators collected from 7,607 English practices between 2011 and 2012.

Study Design

Cross‐sectional study at the practice level. Indicators were allocated to subdomains of processes of care (“quality assurance,” “education and training,” “medicine management,” “access,” “clinical management,” and “patient‐centered care”), health outcomes (“intermediate outcomes” and “patient‐reported health status”), and patient satisfaction. The relationships between the subdomains were hypothesized in a conceptual model and subsequently tested using structural equation modeling.

Principal Findings

The model supported two independent paths. In the first path, “access” was associated with “patient‐centered care” (β = 0.63), which in turn was strongly associated with “patient satisfaction” (β = 0.88). In the second path, “education and training” was associated with “clinical management” (β = 0.32), which in turn was associated with “intermediate outcomes” (β = 0.69). “Patient‐reported health status” was weakly associated with “patient‐centered care” (β = −0.05) and “patient satisfaction” (β = 0.09), and not associated with “clinical management” or “intermediate outcomes.”

Conclusions

This is the first empirical model to simultaneously provide evidence on the independence of intermediate health care outcomes, patient satisfaction, and health status. The explanatory paths via technical quality clinical management and patient centeredness offer specific opportunities for the development of quality improvement initiatives.

Keywords: Primary health care, clinical quality, health care, patient experience, quality indicators, quality of health care, technical quality of care

Providing high‐quality clinical care is a clear priority for most health care systems (Kocher, Emanuel, and DeParle 2010). There is a general agreement that quality of care is a complex and multidimensional construct (Donabedian 1980; Steffen 1988; Lohr, Donaldson, and Harris‐Wehling 1992; Bull 1994; Winefield, Murrell, and Clifford 1995; Evans et al. 2001; Harteloh 2003; Howie, Heaney, and Maxwell 2004; Cooperberg, Birkmeyer, and Litwin 2009; Gardner and Mazza 2012). One commonly accepted definition conceptualizes the quality of health care as to whether individuals can access the health structures and processes of care which they need, and whether the care received is effective, thereby focusing on the domains of access and effectiveness (Campbell, Roland, and Buetow 2000). There is substantial variation in the domains proposed in the different definitions, and, not surprisingly, a range of approaches have been used to measure quality of care focusing on efficiency, technical quality, patient centeredness, patient satisfaction, or health outcomes, among others (Goodwin et al. 2011).

Understanding the nature of the potential associations between these different domains of health care quality and how they can help predict health outcomes has important implications for research (e.g., to inform the choice of measures) and health care configuration (e.g., to inform resource allocation). This issue has been the focus of a substantial number of studies. Some of them have examined the association between the quality of technical aspects of clinical care and patient satisfaction (Safran et al. 1998; Schneider et al. 2001; Gandhi et al. 2002; Chang et al. 2006; Rao et al. 2006; Sequist et al. 2008; Fenton et al. 2012; Llanwarne et al. 2013). Other studies have examined the relationship between access to health care and patient satisfaction (Kontopantelis, Roland, and Reeves 2010), between quality of care and health outcomes (Mold et al. 2012), between patient centeredness and satisfaction (Kinnersley et al. 1999; Paddison et al. 2015a), between patient centeredness and health outcomes (Kinnersley et al. 1999; Shi et al. 2002), and between health outcomes and satisfaction (Marshall, Hays, and Mazel 1996; Alazri and Neal 2003; Sequist et al. 2008).

The lack of consistent findings across these studies (Mead and Bower 2002; Doyle, Lennox, and Bell 2013) can be at least partially attributed to the heterogeneity among them in terms of health system organization and primary care orientation. Crucially, until now, research on this field has been restricted to pairwise examinations (Marshall, Hays, and Mazel 1996; Schneider et al. 2001; Alazri and Neal 2003; Shi et al. 2002; Rao et al. 2006; Kontopantelis, Roland, and Reeves 2010; Mold et al. 2012; Fenton et al. 2012; Llanwarne et al. 2013; Paddison et al. 2015a) or, less frequently, the evaluation of a reduced number of domains of health care quality (Safran et al. 1998; Kinnersley 1999; Gandhi et al. 2002; Chang et al. 2006; Sequist et al. 2008), offering only a partial and fragmented picture of the complex network of associations between them. Simultaneously modeling the association between multiple domains of health care quality in a single (and large) population would address this gap, offering a more complete and comprehensive approach, testing whether the previous piecemeal approach corresponds to an empirical (not just theoretical) model, minimizing confounding and providing more valid estimations of the existing associations.

This study attempted to provide a unifying model by exploring potential relationships between various domains of care known to be markers of “quality.” The aim of this study was to examine the associations between the different domains of quality of primary health care in family (general) practices in England.

Methods

Data Sources

We conducted a cross‐sectional study using data from English family practices. In England, family practices are the places where general practitioners (GPs) work, usually as part of a team which includes nurses, health care assistants, practice managers, receptionists, and other staff. The vast majority of the population is registered with a family practice for the provision of primary care services which are free at the point of care. Computerization is almost complete (with electronic medical records operating in the vast majority of the practices) and driven by participation in the profitable Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), a national pay‐for‐performance scheme (Roland 2004).

Data on indicators for quality of the health care provided by family practices in England for the financial year 2011–2012 were obtained from reporting systems for two major quality improvement initiatives in primary care in England: the QOF (Roland 2004) and the GP Patient Survey (GPPS; Campbell et al. 2009).

The Quality and Outcomes Framework is a voluntary scheme that financially rewards practices for their performance across a range of quality indicators. In the financial year 2011–2012, it included a total of 141 indicators. QOF data can be obtained from the Quality Management and Analysis System (QMAS), which automatically extracts data from the clinical record systems of practices. Practices accumulate points according to their level of achievement for each indicator, each point being associated with a financial benefit.

The GPPS is a survey capturing the experiences of patients who have been continuously registered with a practice for at least 6 months. This survey includes 46 questions and at the time of research was mailed each year to 2.7 million patients. A total of 246 indicators of quality of care as perceived and self‐reported by patients are derived from the survey. Each indicator depends on the percentage of patients from a practice giving a specific answer to an item in the survey (e.g., percentage of patients rating their experience of their GP surgery as “very good”). The overall mortality‐adjusted response rate was 40 percent for the 2011–2012 year. Additional details of the survey are available elsewhere (Campbell et al. 2009).

All the data above described were extracted from the Health and Social Care Information Centre (2015).

Study Sample

The dataset contained a total of 8,433 practices (99 percent of all practices in England). Of these, 310 practices did not contain QOF data, and 99 had no data relating to GPPS (possibly on account of merging and reconfiguring of practices within the data collection time frame relevant to this study) and were excluded. Thirteen practices were also excluded because they offered only nonstandard services (e.g., walk‐in services, addiction services) or had skewed patient populations (e.g., only care home or university students). Additionally, 404 practices had incomplete data on some GPPS indicators (most frequently on the indicator measuring “frequency of seeing preferred GP”) and were excluded, leaving 7,607 practices in the final dataset (91.2 percent of all practices in England). In general, the 404 practices excluded due to incomplete data in some GPPS indicators were very similar (according to the data extracted about their characteristics) to those that remained included.

Development of the Conceptual Model

A conceptual model was developed to describe hypothesized relationships between the different domains of quality of health care and health outcomes. The model, based on the conceptualization of quality of health care proposed by Donabedian (1966), was developed in an iterative process started by two members of the research team (IRC and JMV) and subsequently reviewed and approved by all members of the research team. We operationalized fundamental domains of quality of care relating to structure (access), processes of care (clinical management, person centeredness), and outcomes (intermediate outcomes, health status, and patient satisfaction) and hypothesized the relationships between them (see Appendix SA2). Subsequently, we examined all the indicators available in the two datasets and allocated them to the putative domains of quality, adding domains where a homogeneous set of indicators measuring a distinct area of quality was not covered by existing domains. Indicators that did not provide information for any of the fundamental domains were not included in the study. Although not originally a criterion for the identification of domains, the resulting domains exclusively contained indicators from one of the two data sources, but not both. The allocation of QOF indicators to each of the domains was to a large degree based on the indicators’ classification produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Prescribing and Primary Care Team, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012). The allocation of GPPS indicators was based on previous work that identified a set of composite markers that summarize the different aspects of the survey (Sizmur 2012).

For items in the GPPS, we selected those indicators retaining the maximum amount of information based on the distribution of the scores at practice level (i.e., the indicators corresponding to the response category most frequently selected by respondents). These were consistently those capturing the most positive health care experience (e.g., “very good” experience of making an appointment as opposed to other potential responses to that item). “Health status” indicators were obtained from responses to the EQ‐5D (Brooks 1996), a standardized measure of health outcomes that was administered in the GPPS.

As part of its development process, the original model was redefined because of inadequate fit (see below for details). The final model included the following nine domains (137 indicators): quality assurance (16), education and training (6), medicine management (8), access to the practice (9), clinical management (70), patient‐centered care (12), patient satisfaction (2), intermediate health outcomes (9), and health status (5). The complete list of indicators used to measure each of the domains is available in the Appendix SA3.

Statistical Analysis

We used a hybrid structural equation model (SEM) combining factor and path analysis (Kline and Santor 1999) to empirically test the associations between the quality domains hypothesized in the conceptual model.

Prior to the analysis, an assessment of model identification was made using the two‐step rule (Bollen 1989). Latent variables were constructed to measure each of the quality domains based on the indicators allocated to each of them. The suitability of the allocation of each indicator to its corresponding domain was examined based on their loadings after confirmatory factor analysis and their internal consistency (Cronbach's α). A correlation matrix for all the latent variables was subsequently constructed. Finally, the associations between domains were tested with path analysis.

Statistical analysis comprised the estimation of nonstandardized and standardized coefficients for the conceptual model (using the maximum likelihood estimator) and assessments of model fit (assessment of chi‐squared (Kline 2015), standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR; Kline and Santor 1999), comparative fit index (Hoyle 1995), root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and equation‐level goodness of fit).

We needed to redefine the model because of inadequate fitness. This was performed based on clinical and statistical criteria and consisted in removing from the model the latent variables “records and information” (mostly related to information systems based on alerts) and “overall structure” (accounting for all the structural characteristics of the practices that would affect health care quality). Once an adequate model was successfully identified, we tested a number of alternative similar models to better understand the associations between the different domains and to examine the consistency of our findings against different data modeling approaches (Hays and White 1987). More specifically, five alternative models were tested in order to explore (1) reversed causality for some of the hypothesized associations (e.g., patient satisfaction impacting on self‐reported health rather than vice versa); and (2) impact of allocating indicators into broader domains (e.g., collapsing the domains “quality assurance,” “education and training,” and “medicine management” into a single “structure of care” domain). The initial alternative models failed to converge, and modifications were introduced in the subsequent models with a view of optimizing parsimony and achieving convergence.

All analyses were carried out in STATA v12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA), and we used an α level of 5 percent throughout.

Results

General characteristics of the practices are presented in Table 1. According to the NHS Patient Register, the number of patients registered with the practices in this study during the study period was 54,299,945 (mean number of patients per practice: 7,084; SD = 4,144).

Table 1.

Characteristics of General Practices Included in the Study (N = 7,607)

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of registered patients | 7,084 (4144) | 597; 44,071 |

| Female | 50.37 (5.59) | 20.28; 75.47 |

| Age (%) | ||

| 18–24 years | 9.83 (5.66) | 0; 86.17 |

| 25–34 years | 17.49 (8.19) | 0; 70.07 |

| 35–44 years | 18.43 (5.20) | 0; 44.87 |

| 45–54 years | 18.32 (4.11) | 0; 37.42 |

| 55–64 years | 15.02 (4.43) | 0; 32.92 |

| 65–74 years | 11.20 (4.25) | 0; 28.44 |

| 75–84 years | 6.95 (2.99) | 0; 21.56 |

| ≥85 years | 2.75 (1.61) | 0; 11.62 |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 84.24 (21.90) | 0; 100 |

| Black | 3.26 (6.54) | 0; 64.13 |

| Asian | 8.25 (14.61) | 0; 93.56 |

| Index of multiple deprivationa | 23.52 (12.08) | 2.86; 66.38 |

McLennan et al. 2011. The English Indices of Deprivation 2010: Technical Report. 2011.

Cronbach's α and confirmatory factor analysis loadings indicated adequate internal consistency and structural validity of all nine final domains (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Health Care Quality Domains

| Source | Number of Indicators | Cronbach's α a | Confirmatory Factor Analysis (Loadings Range) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education and training | QOF | 6 | 0.72 (0.67; 0.72) | 0.47; 0.65 |

| Medicine management | QOF | 8 | 0.84 (0.80; 0.85) | 0.35; 0.87 |

| Quality assurance | QOF | 16 | 0.86 (0.85; 0.86) | 0.30; 0.76 |

| Access to the practice | GPPS | 8 | 0.92 (0. 90; 0.92) | 0.49; 0.99 |

| Clinical management | QOF | 70 | 0.94 (0.93;0.94) | 0.07; 0.63 |

| Patient‐centered care | GPPS | 12 | 0.97 (0.96; 0.97) | 0.64; 0.97 |

| Patient satisfaction | GPPS | 2 | 0.96 (NA) | 0.95; 0.96 |

| Intermediate outcomes | QOF | 9 | 0.81 (0.77; 0.81) | 0.39; 0.74 |

| Health status | GPPS | 5 | 0.92 (0.88; 0.93) | 0.39; 0.74 |

Mean (minimum; maximum). GPPS, GP Patient Survey; NA, not applicable; QOF, Quality and Outcomes Framework.

The matrix of correlations between the domains is shown in the Table 3. The highest correlations were observed for the pairs “patient‐centered care” and “patient satisfaction” (r = .88), “clinical management” and “intermediate outcomes” (r = .69), and “medicine management” and “education and training” (r = .67). The highest correlation coefficient for “health status” was with “patient satisfaction” (r = .05) and “patient‐centered care” (−.05).

Table 3.

Correlations between the Health Care Quality Domains

| Quality Assurance | Education and Training | Medicine Management | Access to the Practice | Clinical Management | Patient‐Centered Care | Intermediate Outcomes | Patient Satisfaction | Health Status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality assurance | 1 | 0.634 | 0.605 | 0.026 | 0.284 | 0.078 | 0.197 | 0.078 | 0.003 |

| Education and training | 0.634 | 1 | 0.670 | 0.026 | 0.313 | 0.110 | 0.217 | 0.107 | 0.021 |

| Medicine management | 0.605 | 0.670 | 1 | 0.018 | 0.138 | 0.056 | 0.095 | 0.053 | 0.001 |

| Access to the practice | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.018 | 1 | 0.010 | 0.632 | 0.067 | 0.553 | −0.030 |

| Clinical management | 0.284 | 0.313 | 0.138 | 0.010 | 1 | 0.109 | 0.694 | 0.129 | 0.019 |

| Patient‐centered care | 0.078 | 0.110 | 0.056 | 0.632 | 0.109 | 1 | 0.076 | 0.878 | −0.045 |

| Intermediate outcomes | 0.197 | 0.217 | 0.095 | 0.067 | 0.694 | 0.076 | 1 | 0.077 | 0.020 |

| Patient satisfaction | 0.078 | 0.107 | 0.053 | 0.553 | 0.129 | 0.878 | 0.077 | 1 | 0.051 |

| Health status | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.001 | −0.030 | 0.019 | −0.045 | 0.020 | 0.051 | 1 |

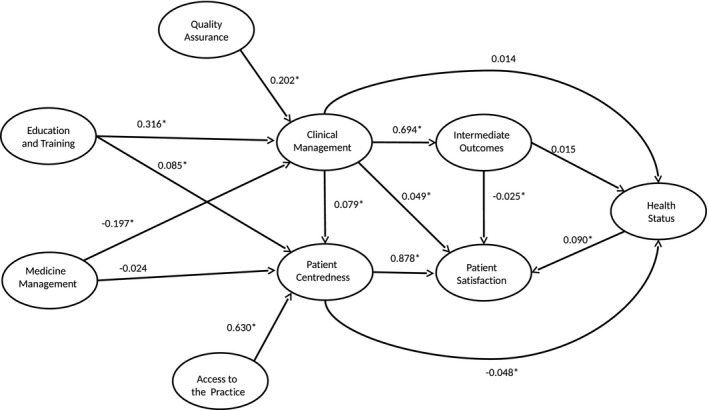

Figure 1 shows the results of the final model used to examine the associations between the quality domains (confidence intervals available in Table 4). The 137 observed variables provided 9,590 variances and covariances, and the model estimated contained 432 parameters with 9,158 degrees of freedom. We report standardized coefficients, which can be interpreted as standard regression coefficients that allow for direct comparison (e.g., a 1 SD increase in “education and training” is associated with a 0.32 SD increase in “clinical management,” but with a smaller 0.09 SD increase in “patient‐centered care”).

Figure 1.

Associations between Health Care Quality and Health Outcome Domains in the Final Structural Equation Model Notes. Statistically significant associations (p < 0.05) are noted with an asterisk (*).

Table 4.

Associations between Health Care Quality in the Final Structural Equation Model

| Structural Effect/Path Coefficient | β | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient‐centered care to Patient satisfaction | 0.878 | 0.872 | 0.885 |

| Clinical management to Intermediate outcomes | 0.694 | 0.678 | 0.709 |

| Access to practice to Patient‐centered care | 0.630 | 0.616 | 0.644 |

| Education and training to Clinical management | 0.316 | 0.272 | 0.360 |

| Quality assurance to Clinical management | 0.202 | 0.166 | 0.238 |

| Medicine management to Clinical management | −0.197 | −0.236 | −0.158 |

| Health status to Patient satisfaction | 0.090 | 0.077 | 0.103 |

| Education and training to Patient‐centered care | 0.085 | 0.052 | 0.118 |

| Clinical management to Patient‐centered care | 0.079 | 0.060 | 0.099 |

| Clinical management to Patient satisfaction | 0.049 | 0.030 | 0.068 |

| Patient‐centered care to Health status | −0.048 | −0.071 | −0.024 |

| Intermediate outcomes to Patient satisfaction | −0.025 | −0.045 | −0.006 |

| Medicine management to Patient‐centered care | −0.024 | −0.053 | 0.006 |

| Intermediate outcomes to Health status | 0.015 | −0.024 | 0.053 |

| Clinical management to Health status | 0.014 | −0.023 | 0.050 |

β, standardized coefficients; CI, confidence interval.

According to the magnitude of the standardized coefficients, the model suggested two distinct paths. In the first path, “access to the practice” was associated with “patient‐centered care” (β = 0.63), which in turn was strongly associated with “patient satisfaction” (β = 0.88). In the second path, “education and training” was associated with “clinical management” (β = 0.32), which in turn was strongly associated with “intermediate outcomes” (β = 0.70). These two paths were substantially independent, with weak associations between “clinical management” and “patient‐centered care” (β = 0.08), and between “clinical management” and “patient satisfaction” (β = 0.05). Finally, “health status” was weakly associated with “patient‐centered care” (β = −0.05) and “patient satisfaction” (β = −0.09), but not with “clinical management” or “intermediate outcomes.”

The chi‐squared test indicated that the model performed significantly poorer than the saturated model (likelihood ratio test of model versus saturated: χ 2 (9,158) = 296,452.6, Prob > χ2 = 0.000). However, this test is sensitive with very large sample sizes, and alternative measures (SRMR and RMSEA, with values of 0.07 and 0.06, respectively) indicated adequate model fit (Steiger 1990). This was, however, not supported by the comparative fit index (0.58), with a value below the recommended 0.9. The coefficient of determination for the whole model (with similar interpretation to R‐squared) was 0.99. Equation‐level goodness of fit statistics showed that the model explained a high proportion of variability in “patient satisfaction” (R‐squared = 78 percent), “intermediate outcomes” (48 percent), and “patient‐centered care” (42 percent). However, the model performed less well for “clinical management” (13 percent) and “health status” (0.3 percent).

Only one of the five alternative models considered successfully converged. The results from this alternative model (available in Appendix SA4) generally supported our main findings, observing positive associations between “structure of care” (derived from indicators from the subdomains “quality assurance,” “education and training,” and “medicine management”) and “clinical management,” which in turn was associated with “intermediate outcomes” and with “patient experience” (derived from indicators from “access to practices,” “patient centeredness,” and “patient satisfaction”). Self‐reported health was not associated with patient experience or with intermediate outcomes.

Discussion

In this study we used a structural equation model to examine the network of associations between multiple domains of the quality of health care provided in family practices in England. We identified two independent paths. The first path links access to practices to patient‐centered care and to patient satisfaction. The second path links education and training to clinical management of care and to intermediate outcomes. Patient‐reported health status was very weakly associated with patient‐centered care and patient satisfaction, and not associated with clinical management or intermediate outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has a number of strengths. It includes data for the great majority of QMAS practices in England (covering over 99 percent of patients). In addition, it simultaneously examines the association between multiple domains of health care quality using robust analytic methods and a large number of evidence‐based indicators that rely on information provided both by clinicians and patients. But some limitations need to be taken into account. First, the cross‐sectional nature of this study makes causal inference problematic. Reversed associations are implausible in most of the cases, but not always (e.g., we hypothesized intermediate outcomes to affect patient satisfaction, but inversed causality is also plausible as more satisfied patients could be more adherent to treatment recommendations, which could result in better intermediate outcomes). Future research using longitudinal designs is needed to better model causal effects. Second, following established recommendations (Hays and White 1987), we considered a number of alternative structural equation models to better understand the associations between the different domains of quality of health care tested in our main model. However, only one of them could be successfully estimated (which generally supported our main findings), and we cannot rule out the possibility of other alternative models leading to a different interpretation of our data. Third, our study was restricted to practice‐level analysis and did not allow us to draw conclusions about patient‐level associations. Practice‐level analysis, however, is of inherent interest and can inform relevant aspects such as resource allocation and primary care configuration. Fourth, data for this study were obtained from two different sources, and each quality domain was based on information from only one of them. This could have resulted in an overestimation of the magnitude of the associations between domains from the same source, and an underestimation of the associations from different sources. Fifth, although we used established measures of family practice quality in England, some limitations intrinsic to both sources may have affected our findings. Concerns relating to a low response rate and low reliability have been raised with respect to the GPPS. However, there is little evidence that low response rates have introduced bias (Campbell et al. 2009), and research shows that most survey questions used in this study meet stringent guidelines for reliability (Lyratzopoulos et al. 2011). QOF indicators measure only a fraction of the health care provided by a practice to their patients, and the analysis of other (nonincentivized) activities might yield different results. Finally, the model did not include practice characteristics such as deprivation or size that have been previously associated with performance. A decision was made not to include those additional variables to facilitate model convergence. Similarly, it would have been desirable to include the model hospital admissions and mortality rates, but this information was not readily available.

Interpretation of Results and Implications for Health Services Organization

The first path suggests that patients’ ease of access to their practice is associated with patient‐centered care and that patient satisfaction is higher in those practices with higher levels of patient‐centered care. The observed relationship between access and patient‐centered care may suggest that, by enhancing access, practices may create a platform from which to develop opportunities for a partnership between patient and clinicians that accounts for the patient's position and feelings. This would support the idea of prioritizing resources for improving access to family practices. The observed relationship between patient‐centered care and patient satisfaction has been reported previously (Kinnersley et al. 1999; Lewin et al. 2001) and has strong face validity. A recent patient‐level study including more than 2 million patients responding to the GP Patient Survey observed that doctor communication was the most important patient experience factor driving satisfaction (Paddison et al. 2015a).

The second path identified suggests that practices with higher levels of training and education are better equipped to deliver high‐quality clinical care, having a more positive impact on intermediate health outcomes. This finding has strong face validity and supports the clinical aspects that are incentivized as part of QOF scheme in the United Kingdom. In addition, it highlights the importance of adequate training, identifying it as a priority area for resource allocation. Interestingly, however, although the education and training provided to health care professionals were associated with better clinical management, its association with patient‐centered care was very weak. This suggests that current training initiatives might have a very strong clinical orientation, in line with observations from previous research (Tsimtsiou et al. 2007). An increased focus on patient‐centered education (which could be achieved, for example, by involving patients in training programs, which have shown to produce sustained gains in levels of interpersonal skills [Greco, Brownlea, and McGovern 2001]) may represent an opportunity of quality improvement worth exploring.

We observed a weak positive association between clinical management and patient‐centered care and satisfaction, which was stronger in our alternative model. Previous studies analyzed the relationship between clinical management and patient experiences in primary care settings, reporting findings ranging from no association (Gandhi et al. 2002; Chang et al. 2006; Rao et al. 2006) to modest positive associations (Schneider et al. 2001; Sequist et al. 2008; Llanwarne et al. 2013). Studies in secondary care reported moderate (Lehrman et al. 2010) or strong (Jha et al. 2008; Isaac et al. 2010; Stein et al. 2014) positive associations. The positive association observed in our study does not support the idea that encouraging doctors to concentrate on technical aspects of care and incentive schemes such as the QOF will lead to deterioration in the doctor–patient relationship, or vice versa.

Unexpectedly, medicine management was negatively associated with clinical management. Although it may be hypothesized that adequate medicine management may be resource consuming and it may occur at the expense of high‐quality processes of care, there is little evidence to support such a view. We are therefore unable to explain the observed association, and more research is needed to confirm this inverse relationship and eventually elucidate the mechanisms by which it might operate.

Although patient‐reported outcome measures have been traditionally regarded as a measure of need rather than performance, in recent years there has been a growing interest in their use for performance assessment of the health system and for benchmarking and quality improvement purposes in health care organizations (Nelson et al. 2015). In our study, self‐reported health status was very weakly associated with patient‐centered care, and we observed no association with clinical management or intermediate outcomes. Similar findings were observed in our alternative model. Our findings are consistent with a previous study which observed no association between patients’ baseline assessments of the quality of primary care they received and subsequent changes in health‐related quality of life and survival (Mold et al. 2012). However, this contrasts with previous primary care‐specific studies supporting a link between primary care supply and positive perceived health (Shi et al. 1999; Shi and Starfield 2000, 2001). More specifically, it has been observed that good primary care experience, in particular enhanced accessibility and continuity, is associated with better self‐reported health both generally and mentally (Shi et al. 2002). A number of aspects need to be taken into account when interpreting the lack of association observed in our study. First, the fact that we used self‐reported health status aggregated at the practice level may have reduced our ability to detect a potential association. An individual patient receiving good quality of primary health care is more likely to have better health outcomes than a patient receiving poor primary health care. However, the same does not necessarily apply at the practice level, as measures of population health are more likely to be influenced by environmental and social factors. Second, the potential impact of processes of care on health outcomes is likely to occur in a longer period of time than, for example, the impact of processes of care on patient satisfaction or intermediate outcomes. The cross‐sectional nature of our study thus hindered our ability to examine this specific relationship. Finally, it is well known that health status is correlated with multiple factors beyond the GP's control. These include genetic variation (it has been estimated that one‐third of the variability of self‐reported health can be attributed to genes [Romeis et al. 2000]), and also other personal, social, economic, and environmental factors (Dahlgren and Whitehead 1991), which were not included in our study. Therefore, a hypothetical small effect such as the one described by Shi et al. (2002) cannot be ruled out by the findings of this study because of the methodological constrains described above. Although we think our model is of relevance in reflecting the status of the health care system, we acknowledge that it may be of more limited value in reflecting health.

Self‐reported health status was weakly associated with patient satisfaction, which supports previous research from the hospital setting (Hays et al. 2006). An inverse association may be plausible in this case (more satisfied patients could have higher adherence to treatment recommendations and therefore have better health outcomes) and has been observed in a previous longitudinal study (Marshall, Hays, and Mazel 1996). However, we tested this inverse association in our alternative model, observing that patient experience was not associated with self‐reported health. Our results might reflect that patients with poorer health constitute a particular group of primary care service users not only in respect of above‐average service use, but also in respect of the range and type of services used, particularly reflective of lower levels of overall satisfaction with health care services. This is in line with a recent study observing that patients with multimorbidity more frequently report worse experiences in primary care (Paddison et al. 2015b). This could have implications for quality improvement initiatives, as segmenting the patient population by their medical needs could enable patients’ feedback to indicate where quality improvements are required for specific groups. Other industries have been successful in understanding where to make improvements for consumers through data segmentation techniques that identify specific groups within the population (Flott et al. 2016).

Conclusion

By including an unprecedented number of factors within a single statistical model, this study was able to describe the network of associations between multiple domains of quality of health care provided in primary care in England. This is the first empirical model simultaneously providing evidence on the independence of all intermediate health care outcomes, patient satisfaction, and health status. The explanatory paths via technical quality clinical management and patient centeredness offer specific opportunities for the development of quality improvement initiatives. Further longitudinal and patient‐level studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Initial Model Proposed to Describe the Associations between the Different Domains of Quality in Primary Care.

Appendix SA3. Observed and Latent Variables Included in the Final Structural Equation Model.

Appendix SA4: Alternative Modeling.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: The authors conducted this work supported through their employment at their respective institutions and through a personal fellowship, as detailed below:

Ignacio Ricci‐Cabello, Sarah Stevens, Robert Griffiths, and Andrew Dalton were supported through their employment at the Nuffield Department of Primary Health Care Sciences (University of Oxford).

John Campbell was supported through his employment at the University of Exeter Medical School.

Jose M. Valderas was supported through a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Clinician Scientist Award (NIHR/CS/010/024).

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest or financial disclosures are declared by any author of this study.

Disclaimer: None.

References

- Alazri, M. H. , and Neal R. D.. 2003. “The Association between Satisfaction with Services Provided in Primary Care and Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.” Diabetic Medicine 20 (6): 486–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K. A. 1989. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, R. 1996. “EuroQol: The Current State of Play.” Health Policy 37 (1): 53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull, A. 1994. “Specifying Quality in Health Care.” Journal of Management in Medicine 8 (2): 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S. M. , Roland M. O., and Buetow S. A.. 2000. “Defining Quality of Care.” Social Science and Medicine 51 (11): 1611–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. , Smith P., Nissen S., Bower P., Elliott M., and Roland M.. 2009. “The GP Patient Survey for Use in Primary Care in the National Health Service in the UK—Development and Psychometric Characteristics.” BMC Family Practice 10: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J. T. , Hays R. D., Shekelle P. G., MacLean C. H., Solomon D. H., Reuben D. B., Roth C. P., Kamberg C. J., Adams J., Young R. T., and Wenger N. S.. 2006. “Patients’ Global Ratings of Their Health Care Are Not Associated with the Technical Quality of Their Care.” Annals of Internal Medicine 144 (9): 665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooperberg, M. R. , Birkmeyer J. D., and Litwin M. S.. 2009. “Defining High Quality Health Care.” Urologic Oncology 27 (4): 411–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren, G. , and Whitehead M.. 1991. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm: Institute for Future Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian, A. 1966. “Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care.” The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 44 (3): 166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian, A. . 1980. The Definition of Quality and Approaches to Its Assessment. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, C. , Lennox L., and Bell D.. 2013. “A Systematic Review of Evidence on the Links between Patient Experience and Clinical Safety and Effectiveness.” BMJ Open 3 (1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D. B. , Edejer T. T., Lauer J., Frenk J., and Murray C. J.. 2001. “Measuring Quality: From the System to the Provider.” International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care 13 (6): 439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, J. J. , Jerant A. F., Bertakis K. D., and Franks P.. 2012. “The Cost of Satisfaction: A National Study of Patient Satisfaction, Health Care Utilization, Expenditures, and Mortality.” Archives of Internal Medicine 172 (5): 405–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flott, K. M. , Graham C., Darzi A., and Mayer E.. 2016. “Can We Use Patient‐Reported Feedback to Drive Change? The Challenges of Using Patient‐Reported Feedback and How They Might Be Addressed.” BMJ Quality & Safety, doi:10.1136/bmjqs‐2016‐005223. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, T. K. , Francis E. C., Puopolo A. L., Burstin H. R., Haas J. S., and Brennan T. A.. 2002. “Inconsistent Report Cards: Assessing the Comparability of Various Measures of the Quality of Ambulatory Care.” Medical Care 40 (2): 155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, K. , and Mazza D.. 2012. “Quality in General Practice—Definitions and Frameworks.” Australian Family Physician 41 (3): 151–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, N. , Dixon A., Poole T., and Raleigh V.. 2011. Improving the Quality of Care in General Practice. Report of an Independent Inquiry Commissioned by The King's Fund. London: The King's Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, M. , Brownlea A., and McGovern J.. 2001. “Impact of Patient Feedback on the Interpersonal Skills of General Practice Registrars: Results of a Longitudinal Study.” Medical Education 35 (8): 748–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harteloh, P. P. 2003. “The Meaning of Quality in Health Care: A Conceptual Analysis.” Health Care Analysis: HCA: Journal of Health Philosophy and Policy 11 (3): 259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R. D. , and White K.. 1987. “The Importance of Considering Alternative Structural Equation Models in Evaluation Research.” Evaluation & the Health Professions 10 (1): 90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays, R. D. , Eastwood J. A., Kotlerman J., Spritzer K. L., Ettner S. L., and Cowan M.. 2006. “Health‐Related Quality of Life and Patient Reports about Care Outcomes in a Multidisciplinary Hospital Intervention.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine 31 (2): 173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Social Care Information Centre . 2015. “Indicator Portal” [accessed on January 13, 2016]. Available at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/indicatorportal

- Howie, J. G. , Heaney D., and Maxwell M.. 2004. “Quality, Core Values and the General Practice Consultation: Issues of Definition, Measurement and Delivery.” Family Practice 21 (4): 458–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R. H. 1995. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues and Applications. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, T. , Zaslavsky A. M., Cleary P. D., and Landon B. E.. 2010. “The Relationship between Patients’ Perception of Care and Measures of Hospital Quality and Safety.” Health Services Research 45 (4): 1024–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha, A. K. , Orav E. J., Zheng J., and Epstein A. M.. 2008. “Patients’ Perception of Hospital Care in the United States.” New England Journal of Medicine 359 (18): 1921–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnersley, P. , Stott N., Peters T. J., and Harvey I.. 1999. “The Patient‐Centredness of Consultations and Outcome in Primary Care.” The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 49 (446): 711–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. , and Santor D. A.. 1999. “Principles & Practice of Structural Equation Modelling.” Canadian Psychology 40 (4): 381. [Google Scholar]

- Kocher, R. , Emanuel E. J., and DeParle N. A.. 2010. “The Affordable Care Act and the Future of Clinical Medicine: The Opportunities and Challenges.” Annals of Internal Medicine 153 (8): 536–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontopantelis, E. , Roland M. O., and Reeves D.. 2010. “Patient Experience of Access to Primary Care: Identification of Predictors in a National Patient Survey.” BMC Family Practice 11: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrman, W. G. , Elliott M. N., Goldstein E., Beckett M. K., Klein D. J., and Giordano L. A.. 2010. “Characteristics of Hospitals Demonstrating Superior Performance in Patient Experience and Clinical Process Measures of Care.” Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR 67 (1): 38–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, S. A. , Skea Z. C., Entwistle V., Zwarenstein M., and Dick J.. 2001. “Interventions for Providers to Promote a Patient‐Centred Approach in Clinical Consultations.” The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llanwarne, N. R. , Abel G. A., Elliott M. N., Paddison C. A., Lyratzopoulos G., Campbell J. L., and Roland M.. 2013. “Relationship between Clinical Quality and Patient Experience: Analysis of Data from the English Quality and Outcomes framework and the National GP Patient Survey.” Annals of Family Medicine 11 (5): 467–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr, K. N. , Donaldson M. S., and Harris‐Wehling J.. 1992. “Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance, V: Quality of Care in a Changing Health Care Environment.” QRB Quality Review Bulletin 18 (4): 120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyratzopoulos, G. , Elliott M. N., Barbiere J. M., Staetsky L., Paddison C. A., Campbell J., and Roland M.. 2011. “How Can Health Care Organizations Be Reliably Compared? Lessons from a National Survey of Patient Experience.” Medical Care 49 (8): 724–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, G. N. , Hays R. D., and Mazel R.. 1996. “Health Status and Satisfaction with Health Care: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64 (2): 380–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan, D. , Barnes H., Noble M., Davies J., Garratt E., and Dibben C.. 2011. The English Indices of Deprivation 2010. London: Department for Communities and Local Government. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, N. , and Bower P.. 2002. “Patient‐Centred Consultations and Outcomes in Primary Care: A Review of the Literature.” Patient Education and Counselling 48 (1): 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mold, J. W. , Lawler F., Schauf K. J., and Aspy C. B.. 2012. “Does Patient Assessment of the Quality of the Primary Care They Receive Predict Subsequent Outcomes? An Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) Study.” Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM 25 (4): e1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, E. C. , Eftimovska E., Lind C., Hager A., Wasson J. H., and Lindblad S.. 2015. “Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Practice.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddison, C. A. , Abel G. A., Roland M. O., Elliott M. N., Lyratzopoulos G., and Campbell J. L.. 2015a. “Drivers of Overall Satisfaction with Primary Care: Evidence from the English General Practice Patient Survey.” Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy 18 (5): 1081–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddison, C. A. , Saunders C. L., Abel G. A., Payne R. A., Campbell J. L., and Roland M.. 2015b. “Why Do Patients with Multimorbidity in England Report Worse Experiences in Primary Care? Evidence from the General Practice Patient Survey.” BMJ Open 5 (3): e006172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescribing and Primary Care Team, Health and Social Care Information Centre . 2012. “Quality and Outcomes Framework, Achievement, Prevalence and Exceptions Data, 2011/12” [accessed on January 13, 2016]. Available at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB08135/qof-11-12-rep.pdf

- Rao, M. , Clarke A., Sanderson C., and Hammersley R.. 2006. “Patients’ Own Assessments of Quality of Primary Care Compared with Objective Records Based Measures of Technical Quality of Care: Cross Sectional Study.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 333 (7557): 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland, M. 2004. “Linking Physicians’ Pay to the Quality of Care—A Major Experiment in the United Kingdom.” New England Journal of Medicine 351 (14): 1448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeis, J. C. , Scherrer J. F., Xian H., Eisen S. A., Bucholz K., Heath A. C., Goldberg J., Lyons M. J., Henderson W. G., and True W. R.. 2000. “Heritability of Self‐Reported Health.” Health Services Research 35 (5): 995–1010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran, D. G. , Taira D. A., Rogers W. H., Kosinski M., Ware J. E., and Tarlov A. R.. 1998. “Linking Primary Care Performance to Outcomes of Care.” The Journal of Family Practice 47 (3): 213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, E. C. , Zaslavsky A. M., Landon B. E., Lied T. R., Sheingold S., and Cleary P. D.. 2001. “National Quality Monitoring of Medicare Health Plans: The Relationship Between Enrollees’ Reports and the Quality of Clinical Care.” Medical Care 39 (12): 1313–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist, T. D. , Schneider E. C., Anastario M., Odigie E. G., Marshall R., Rogers W. H., and Safran D. G.. 2008. “Quality Monitoring of Physicians: Linking Patients’ Experiences of Care to Clinical Quality and Outcomes.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 23 (11): 1784–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L. , and Starfield B.. 2000. “Primary Care, Income Inequality, and Self‐Rated Health in the U.S.” International Journal of Health Services 30: 541–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L. , and Starfield B.. 2001. “Primary Care, Income Inequality, and Racial Mortality in U.S. Metropolitan Areas.” American Journal of Public Health 91 (8): 1246–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L. , Starfield B., Kennedy B., and Kawachi I.. 1999. “Income Inequality, Primary Care, and Health Indicators.” Journal of Family Practice 48: 275–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L. , Starfield B., Politzer R., and Regan J.. 2002. “Primary Care, Self‐Rated Health, and Reductions in Social Disparities in Health.” Health Services Research 37 (3): 529–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sizmur, S. 2012. Composite Domain Markers for GPPS: Analysis Report. Oxford, UK: Picker Institute Europe; [accessed on January 13, 2016]. Available at https://indicators.ic.nhs.uk/download/Patient%20experience/Specification/COMPOSITE_DOMAIN_MARKERS_FOR_GPPS.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, G. E. 1988. “Quality Medical Care: A Definition.” JAMA 260 (1): 56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J. H. 1990. “Structural Model Evaluation and Modification: An Interval Estimation Approach.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 25 (2): 173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein, S. M. , Day M., Karia R., Hutzler L., and Bosco J. A.. 2014. “Patients’ Perceptions of Care Are Associated With Quality of Hospital Care: A Survey of 4605 Hospitals.” American Journal of Medical Quality: The Official Journal of the American College of Medical Quality 30 (4): 382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsimtsiou, Z. , Kerasidou O., Efstathiou N., Papaharitou S., Hatzimouratidis K., and Hatzichristou D.. 2007. “Medical Students’ Attitudes toward Patient‐Centred Care: A Longitudinal Survey.” Medical Education 41 (2): 146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winefield, H. R. , Murrell T. G., and Clifford J.. 1995. “Process and Outcomes in General Practice Consultations: Problems in Defining High Quality Care.” Social Science and Medicine 41 (7): 969–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Initial Model Proposed to Describe the Associations between the Different Domains of Quality in Primary Care.

Appendix SA3. Observed and Latent Variables Included in the Final Structural Equation Model.

Appendix SA4: Alternative Modeling.