Abstract

Background

We have reported that prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE)-induced deficits in dentate gyrus (DG) long-term potentiation (LTP) and memory are ameliorated by the histamine H3 receptor inverse agonist ABT-239. Curiously, ABT-239 did not enhance LTP or memory in control offspring. Here, we initiated an investigation of how PAE alters histaminergic neurotransmission in the DG and other brain regions employing combined radiohistochemical and electrophysiological approaches in vitro to examine histamine H3 receptor number and function.

Methods

Long-Evans rat dams voluntarily consumed either a 0% or 5% ethanol solution four-hours each day throughout gestation. This pattern of drinking, which produces a mean peak maternal serum ethanol concentration of 60.8 ± 5.8 mg/dL, did not affect maternal weight gain, litter size or offspring birth weight.

Results

Radiohistochemical studies in adult offspring revealed that specific [3H]-A349821 binding to histamine H3 receptors was not different in PAE rats compared to controls. However, H3 receptor-mediated Gi/Go protein-effector coupling, as measured by methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding, was significantly increased in cerebral cortex, cerebellum and DG of PAE rats compared to control. A LIGAND analysis of detailed methimepip concentration-response curves in DG indicated that PAE significantly elevates receptor-effector coupling by a lower affinity H3 receptor population without significantly altering the affinities of H3 receptor subpopulations. In agreement with the [35S]-GTPγS studies, a similar range of methimepip concentrations also inhibited electrically-evoked fEPSP responses and increased paired-pulse ratio, a measure of decreased glutamate release, to a significantly greater extent in DG slices from PAE rats than in controls.

Conclusion

These results suggest that a PAE-induced elevation in H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of glutamate release from perforant path terminals as one mechanism contributing the LTP deficits previously observed in the DG of PAE rats, as well as providing a mechanistic basis for the efficacy of H3 receptor inverse agonists for ameliorating these deficits.

Keywords: Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, Histamine H3 Receptor, Methimepip, Glutamate, Dentate Gyrus

INTRODUCTION

It is well established that drinking during pregnancy can cause long-term neurobehavioral impairments in affected offspring (see review by Kodituwakku, 2009). Children with FASD exhibit a broad range of cognitive difficulties and behavioral-emotional problems (Mattson et al. 2013). Further, preclinical studies over the past thirty-five years have confirmed that prenatal or early postnatal exposure to alcohol produces a variety of behavioral deficits in affected offspring including behaviors homologous to behaviors altered in patients with FASD (for reviews, Riley, 1990; Kelley et al., 2009; Schneider et al., 2011; Patten et al, 2014). Some of these behavioral deficits have been associated with functional damage to specific areas of the brain, such as the hippocampal formation, a brain region that appears to be particularly sensitive to perinatal ethanol exposure (Sutherland et al., 1997; Perrone-Bizzozero et al., 1998; Miki et al., 2008; Samudio-Ruiz et al., 2009; Titterness and Christie, 2012; Brady et al., 2012). While multiple neurotransmitter systems are affected by exposure to alcohol during development (see review by Valenzuela et al., 2012), efforts to link these prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE)-induced neurochemical alterations with specific functional and behavioral changes in PAE offspring has been limited.

We have reported subtle PAE-induced memory deficits in adult rat offspring whose mothers consumed moderate quantities of ethanol during pregnancy (Savage et al., 2010). Analogous to patients with FASD, these deficits become more apparent with more challenging behavioral tasks (Sutherland et al. 2000; Weeber et al., 2001, Savage et al., 2002). “Baseline” physiological responses appear to be intact in our PAE rats while more complex, activity-dependent changes in synaptic plasticity are more sensitive to PAE (Sutherland et al., 1997; Savage et al., 1998; Costa et al., 2000). A series of combined neurochemical and physiologic studies provided evidence suggesting that presynaptic mechanisms associated with activity-dependent increases in glutamate release from perforant path terminals in dentate gyrus are one mechanism contributing to the LTP deficits observed in our PAE rat offspring (Perrone-Bizzozero et al., 1998; Savage et al., 1998, 2002; Galindo et al., 2004)

Collectively, these observations led us to search for agents that target presynaptic mechanisms regulating neurotransmitter release, which might ameliorate PAE-induced deficits in synaptic plasticity and learning. Agents acting as antagonists or inverse agonists at histamine H3 receptors is one candidate receptor mechanism. These drugs act by blocking a presynaptic histamine H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of the release of a variety of neurotransmitters including histamine (Arrang et al., 1983), other monoamines (Schlicker et al., 1988; 1989; 1993) and acetylcholine (Clapham & Kilpatrick, 1992). While activation of H3 receptors also inhibits glutamate release (Brown & Haas, 1999; Garduno-Torres et al., 2007), the question of whether H3 receptor inverse agonists or antagonists can enhance glutamate release under basal or activity-dependent conditions has yet to be demonstrated. Collectively, more than a dozen H3 receptor antagonists or inverse agonists have been shown to have procognitive effects in a variety of animal models of learning and memory (see reviews by Haas et al., 2008; Esbenschade et al., 2008; Brioni et al., 2011; Nikolic et al., 2014).

Initial studies in our laboratory revealed that the H3 receptor inverse agonist ABT-239 reverses PAE-induced deficits in LTP (Varaschin et al., 2010) and learning (Savage et al., 2010). Curiously, ABT-239 did not enhance either LTP or learning in control offspring. Further, treatment of control offspring with the selective H3 receptor agonist methimepip (Kitbunnadaj et al., 2005) mimicked the in vivo LTP deficit observed in saline-treated PAE rat offspring (Varaschin et al., 2014). Taking these observations together, we hypothesized that PAE elevates histamine H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of excitatory neurotransmission in the dentate gyrus. In an effort to begin investigating the mechanistic basis for the effects of PAE on histaminergic neurotransmission, we measured the number and function of H3 receptors using a combination of radiohistochemical studies in various brain regions in conjunction with in vitro electrophysiological recordings in the same specific region of the dorsal dentate gyrus where we conducted in vivo electrophysiological recordings previously (Varaschin et al., 2010, 2014). We speculated that PAE elevates H3 receptor density in the dentate gyrus leading to heightened H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of excitatory transmission at the performant path – dentate granule cell synapse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

[3H]-A349821 was generously donated by Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL, USA). All other reagents were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich Corp (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless indicated otherwise in parenthetical text.

Voluntary Drinking Paradigm

All procedures involving the use of live rats were approved by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Long-Evans rats (Harlan Industries, Indianapolis, IN, USA) housed at 22 °C on a reverse 12-hour dark/12-hour light schedule (lights on from 2100 to 0900 hours) and provided Harlan 2920 rodent chow and tap water ad libitum. The prenatal alcohol exposure and breeding procedures were the same as described previously (Savage et al., 2010). After one-week of acclimation to the animal facility, all female breeders were single-housed and allowed to drink 5% ethanol in 0.066% saccharin in tap water for four hours each day from 1000 to 1400 hours. Daily four-hour ethanol consumption was monitored for at least two weeks and then the mean daily ethanol consumption determined for each female. Females whose mean daily ethanol consumption was greater than one standard deviation below the group mean, typically about 12–15% of the entire group, were removed from the study. The remainder of the females were assigned to either a saccharin control or 5% ethanol drinking group and matched such that the mean pre-pregnancy ethanol consumption by each group was similar. Subsequently, females were placed with proven male breeders until pregnant, as indicated by the presence of a vaginal plug.

Beginning on Gestational Day 1 (GD1), rat dams were provided saccharin water containing either 0% or 5% ethanol for four hours each day, from 1000 to 1400 hours. The volume of saccharin water provided to the control group was matched to the mean volume of saccharin water consumed by the ethanol group. Daily four-hour ethanol consumption was recorded for each dam through GD21, after which ethanol consumption was discontinued.

At birth, litters were culled to ten pups each. Offspring were weaned at 24 days of age and group-housed, two males or three female per cage until experimental use. Female offspring were used in all of the histochemical and biochemical procedures and male offspring were used in all of the electrophysiological procedures.

Serum Ethanol Assessment

Separate sets of twelve rat dams were used during two of the breeding rounds to assess the peak serum ethanol concentration. These dams were subjected to the same voluntary drinking paradigm as described above except that on GDs 13, 15 and 17, each dam was briefly anesthetized with isoflurane and a 100 μL blood sample drawn from the tail vein 45 minutes after the introduction of the drinking tubes. The serum separated and the samples assayed for ethanol using a modification of the Lundquist assay (Lundquist, 1959). No offspring from the dams used in the serum ethanol assessment were used in the experimental procedures described below.

Histological Sectioning

Eight- to twelve-week-old offspring were sacrificed by rapid decapitation. Whole brains were dissected, frozen in isopentane chilled in a dry ice/methanol bath and stored in airtight containers at −80 °C until sectioning. Twelve-μm-thick microtome cryostat sections were collected in the sagittal plane corresponding to Lateral 1.40 mm in the Paxinos & Watson stereotaxic atlas of rat brain (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). This plane contained the same region of the superior blade of the dorsal dentate gyrus where recordings were made in the in vitro electrophysiological studies described below, as well as our previous in vivo electrophysiological studies (Varaschin et al, 2010, 2014). The sections were thaw-mounted onto pre-cleaned Superfrost-Plus® microscope slides (ColePalmer, Court Vernon Hills, IL, USA) and stored at −80 °C in airtight containers until incubation. Characterization of [3H]-A349821 binding (Figure 1) was conducted in a separate set of untreated control rats. Separate sets of control and PAE offspring were used for the: 1) “Two-point” saturation of [3H]-A349821 binding study (Table 2), 2) brain region survey of methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding (Figures 2A & 2B) and 3) a more detailed methimepip dose-response study (Figure 3 and Table 3).

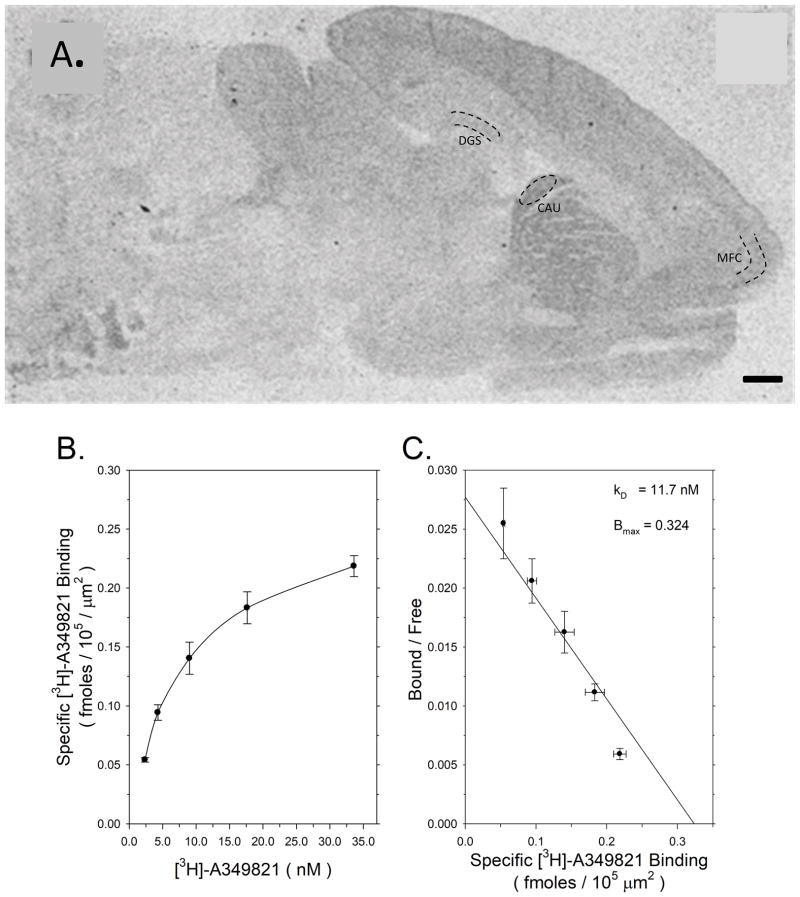

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of [3H]-A349821 binding in control offspring. 1A: Representative autoradiogram of total [3H]-A349821 binding in a sagittal section from an untreated control rat. The three brain regions where binding measurements were made, as denoted by black dotted lines, were the superior blade of the dentate gyrus stratum moleculare (DGS) the dorsal medial caudate nucleus (CAU) and the medial frontal cortex (MFC). The black bar in lower right corner denotes a distance of 1 mm. 1B: Saturation of specific [3H]-A349821 binding in medial frontal cortex of control offspring. Data points are the mean ± SEM of binding expressed as femtomoles/105 μm2 at five different concentrations of radioligand in six untreated control rat offspring. 1C: Scatchard transformation of the saturation of specific [3H]-A349821 binding from Figure 1B.

TABLE 2.

Impact of PAE on specific [3H]-A349821 binding at half-maximally and three-quarter-saturating concentrations of radioligand in three brain regions in adult rat. Data values are the mean ± (SEM), expressed as femtomoles bound/105 μm2, in seven pairs of control and PAE rat offspring.

| [3H]-A349821 (nM): | 9.0 nM

|

33.6 nM

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRAIN REGION | Saccharin Control | Prenatal Alcohol-exposed | Saccharin Control | Prenatal Alcohol-exposed |

| Dentate Gyrus (Superior blade Stratum moleculare) | 0.080 | 0.082 | 0.229 | 0.228 |

| (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.029) | (0.024) | |

| Medial Frontal Cortex (Cingulate Area 3) | 0.143 | 0.149 | 0.253 | 0.300 |

| (0.014) | (0.010) | (0.034) | (0.027) | |

| Caudate Nucleus (Dorso-medial) | 0.231 | 0.237 | 0.453 | 0.457 |

| (0.019) | (0.013) | (0.039) | (0.035) | |

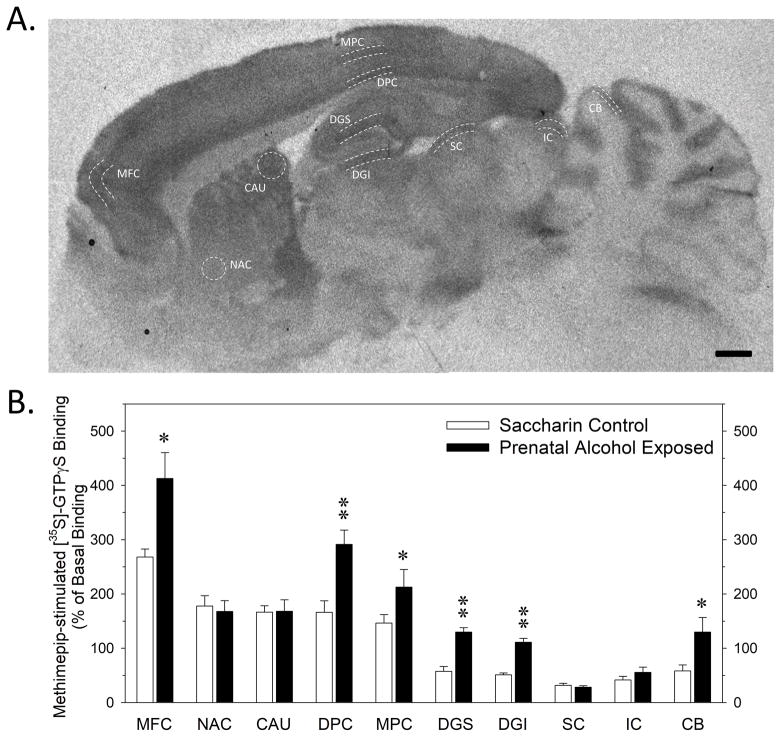

FIGURE 2.

Impact of PAE on H3 receptor agonist-stimulated receptor-effector coupling in various brain regions of adult rat offspring. 2A: Representative autoradiogram of total [35S]-GTPγS binding in the presence of 2 μM methimepip in a sagittal section from a saccharin control rat. The ten brain regions where binding measurements were made, as denoted by white dotted lines, were the medial frontal cortex (MFC), nucleus accumbens core (NAC), dorsal medial caudate nucleus (CAU), deep layer- and middle layer of the medial parietal cortex (DPC, MPC), superior and inferior blades of the dentate gyrus stratum moleculare (DGS, DGI) superior colliculus (SC), inferior colliculus (IC) and cerebellar stratum moleculare (CB). The black bar in the lower right corner denotes of 1 mm. 2B: Effect of PAE on methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding. Data bars represent the mean ± SEM of 7 pairs of control and PAE rats. Asterisks denote data significantly greater than control (* p < 0.05; **- p < 0.005).

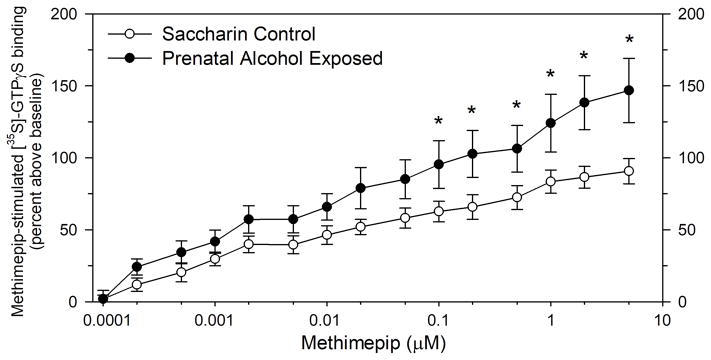

FIGURE 3.

Effect of increasing concentrations of methimepip on [35S]-GTPγS binding in the superior blade of the dorsal dentate gyrus stratum moleculare in control and PAE rats. Data points represent the mean ± the SEM, expressed as percent of basal [35S]-GTPγS binding, in eight pairs of control and PAE rats. Asterisks denote methimepip concentrations at which methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was significantly greater in PAE rats compared to controls (* - p < 0.05).

TABLE 3.

Impact of PAE on the kinetic characteristics of methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding in the superior blade of dorsal dentate gyrus. Data values are the mean ± (SEM), expressed as femtomoles bound/105 μm2, in seven pairs of control and PAE rat offspring.

| Dentate Gyrus | Remax1a | Kd1b | Remax2c | Kd2d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharin Control | 48.4 | 0.868 | 46.3 | 422 |

| (5.6) | (0.188) | (5.9) | (116) | |

| Prenatal Alcohol Exposed | 73.5 | 0.834 | 79.2* | 643 |

| (12.0) | (0.241) | (11.1) | (239) |

Estimated maximal response to the higher affinity H3 receptor population (% of basal response).

Estimated affinity constant for methimepip stimulation of the high affinity H3 receptors (μM).

Estimated maximal response to the lower affinity H3 receptor population (% of basal response).

Estimated affinity constant for methimepip-stimulation of the lower affinity H3 receptors (μM).

denotes data significantly greater than the saccharin control group (p=0.023)

Specific [3H]-A349821 Binding to Histamine H3 Receptors

Histamine H3 receptor density measures were performed using methods similar to those described by Witte et al., (2006). Tissue sections were incubated in buffer (150 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4 at 25 °C) with different concentrations of [3H]-A349821 (Abbott Laboratories, specific activity = 54.0 Ci/mmole) for 60 minutes at 25 °C in the absence (total binding) and presence of 10 μM thioperamide (non-specific binding). After incubation, sections were rinsed twice for 30 seconds each in ice-cold incubation buffer, dipped in ice-cold distilled water, dried and placed in a vacuum desiccator overnight. Sections were then exposed to Kodak Biomax MR Film for four months and then the film developed in Kodak D-19 (1:1) and fixed. Microdensitometric measurement of [3H]-A349821 binding was performed using Media Cybernetics Image Pro Plus® (Silver Spring, MD) on an Olympus BH-2 microscope at a total image magnification of 3.125X. An optical density standard curve, expressed in pCi/105 μm2, was established based on autoradiograms of tritium standards. Total and non-specific [3H]-A349821 binding were measured in the superior blade of the dorsal dentate gyrus stratum moleculare, medial frontal cortex and the dorso-medial caudate nucleus. Specific [3H]-A349821 binding, expressed as fmoles bound/105 μm2, was defined as the difference between total [3H]-A349821 binding and non-specific [3H]-A349821 binding.

Methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS Binding

Histamine H3 agonist-stimulated receptor-effector coupling was performed using methods originally described by Sim et al. (1995). Tissue sections were pre-incubated for 10 minutes in incubation buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 2 mM GDP and 100 nM DPCPX; pH 7.4 at 25 °C), and then incubated with 100 pM [35S]-GTPγS (Perkin Elmer, specific activity = 1250 Ci/mmole) for 90 minutes at 25 °C in the absence and presence or 10 μM unlabeled GTPγS. In addition, sections were incubated with 2 μM methimepip in an initial study to obtain measures of H3 receptor agonist-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding. In a subsequent more-detailed concentration-response study, sections were incubated with one of fifteen different concentrations of methimepip ranging from 0.1 nM to 5 μM After incubation, sections were rinsed twice for 15 seconds each in ice-cold incubation buffer, dipped in ice-cold distilled water, dried and placed in a vacuum desiccator overnight. Sections were then exposed to Kodak Biomax MR Film for four days and then the film developed in Kodak D-19 (1:1) and fixed. Microdensitometric measurements of [35S]-GTPγS binding were performed similar to those described above except that the optical density standard curve was established based on autoradiograms of 14carbon standards. Binding measurements were performed over ten different brain regions. Basal [35S]-GTPγS binding was defined as the difference between binding in the absence and presence of 10 μM unlabeled GTPγS. Methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was defined as the difference between [35S]-GTPγS binding in the presence of methimepip and basal [35S]-GTPγS binding. Percent increase in agonist-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was defined as methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding divided by basal [35S]-GTPγS binding.

Extracellular Slice Recording Procedures

Eight-week-old rat offspring were deeply anesthetized with ketamine (250 mg/kg i.p.), quickly decapitated and the brain removed. Coronal slices containing the dorsal dentate gyrus were obtained as described previously (Mameli et al., 2005). Briefly, whole brain coronal slices (400 μm thick) were obtained using a vibrating microtome immersed in ice-cold cutting solution containing 3 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 6 mM MgSO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 220 mM sucrose, and 0.43 mM ketamine. Slices were then allowed to recover for 40 min at 32 °C in artificial cerebral-spinal fluid (ACSF) containing 126 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose and oxygenated with 95% O2/5% CO2. After recovery, slices were maintained in oxygenated ACSF at room temperature until recording. Upon transfer to recording chambers, slices were perfused at a rate of 2 mL/min with 32 °C oxygenated ACSF containing different treatment conditions. Next, a concentric bipolar electrode (FHC, Bowdoin, ME) was placed in the medial portion of the superior blade of the dentate gyrus stratum moleculare, and a recording glass electrode (resistance ~3–5 Ω) filled with ACSF placed in the same layer, about 200 μm lateral to the stimulating electrode. Electrically-evoked field excitatory post-synaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were triggered using a Master-8 stimulator and an Iso-flex stimulus isolator (AMPI, Jerusalem, Israel), and recorded using a Digitizer model 1440 and AxoPatch 200 amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) with low-pass filter set at 2 kHz.

Input/output curves were generated using a stimulus intensity range of 0.05 to 1.2 mA to determine the stimulus intensity sufficient to elicit maximal fEPSP amplitude. All subsequent recordings were performed with a test stimulus intensity sufficient to elicit 40% of the maximal fEPSP response (ES40). A paired-pulse stimulation of the medial perforant path protocol, consisting of two pulses of 75 μs duration and 40 ms apart was used. Pulses were delivered every 30 seconds over ten minutes to establish a baseline response. Slices were then incubated for ten minutes with one of three concentrations of methimepip (0.3, 1.0, or 3.0 μM). First pulse fEPSP data obtained over the last four minutes during each drug treatment condition was averaged as a single measure and normalized to the baseline fEPSP amplitude. Paired-pulse ratio (PPR) was measured as the ratio of the fEPSP amplitude elicited by the second pulse divided by the fEPSP amplitude elicited by the first pulse and averaged as a single value over the last four minutes of each treatment condition.

Study Design Issues and Statistical Analyses

For each type of study, no more than one offspring per litter was used in a given experiment to avoid the prospect of “litter effects”. Sample size determinations for these experiments indicated a minimum of n=6, based on past receptor binding studies and in vitro slice electrophysiological studies in our laboratories with an minimum expected difference in group means of 20%, an expected standard deviation of 10%, and a desired power of 0.8 at an alpha value of 0.05. Seven or eight pairs of subjects were used in all of the studies. There were no exclusion criteria and no data were excluded from the analyses. All microdensitometric measurements and slice incubations, except the electrophysiological recordings, were performed by investigators blinded to the prenatal treatment condition of the samples, and samples were analyzed randomly in pairs. Although the investigator was not blinded to treatment in the slice electrophysiology studies, the only a priori rejection criterion used in the study was the stability of the baseline fEPSP amplitude (a maximum of 20% drift was acceptable) and no slice met that criterion. Bias on the PPR and on the effect of methimepip on the EPSP amplitude is minimal because no decision to include/exclude data points were made after bath application of the drug.

All statistical procedures and graphical illustrations were performed using SigmaPlot® 11 (Systat Software Inc. San Jose, CA, USA). The effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on maternal weight gain, litter size, offspring birth weight (Table 1) were conducted using a Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test. Specific [3H]-A349821 binding (Table 2), methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding at 2 μM (Figure 2B) and LIGAND kinetic estimates of methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding (Table 3) were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Prenatal alcohol effects in the methimepip concentration-[35S]-GTPγS binding response study (Figure 3), input/output responses (Figure 4) and methimepip effects on first-pulse fEPSPs and PPRs (Figure 5) were analyzed using a repeated measures two-way ANOVAs. Post-hoc pairwise multiple comparisons were made using the Student-Newman-Keuls method. All data is expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and a value of p < 0.05 was deemed as statistically significant.

Table 1.

Effects of daily four-hour consumption of 5% ethanol on female rat dams and their offspring

| Saccharin Control | Prenatal Alcohol-exposed | |

|---|---|---|

| Daily Four-hour 5% Ethanol Consumption | NA | 1.98 ± 0.07a |

| (44) | ||

| Maternal Serum Ethanol Concentration | NA | 60.8 ± 5.8b |

| (24) | ||

| Maternal Weight Gain During Pregnancy | 112 ± 5c | 100 ± 4 |

| (41) | (44) | |

| Litter Size | 11.4 ± 0.4d | 10.8 ± 0.4 |

| (41) | (44) | |

| Offspring Birth Weight | 9.90 ± 0.52e | 9.00 ± 0.29 |

| (41) | (44) |

Mean ± S.E.M. grams ethanol consumed/kg body weight/day

Mean ± S.E.M. mg ethanol/dL serum, 45 minutes after introduction of the drinking tubes

Mean ± S.E.M. grams increase in body weight from GD 1 through GD 21

Mean ± S.E.M. number of live births/litter

Mean ± S.E.M. grams pup birth weight

NA - Not applicable

(n) - Group sample size

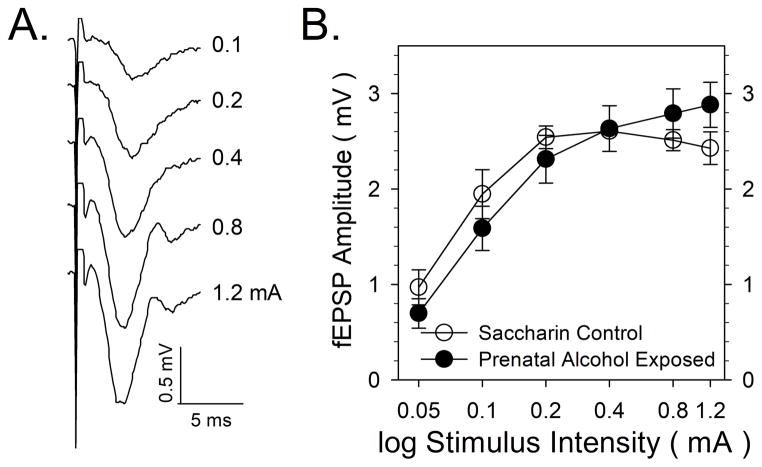

FIGURE 4.

Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) on baseline field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) recorded from dorsal dentate gyrus granule cells. 4A: Representative traces illustrating fEPSP responses from a control rat to single pulses of 0.1 to 1.2 mA stimulus intensity. 4B: A summary of fEPSP response data in control and PAE rats. Data points represent the mean ± SEM fEPSP response amplitude, expressed in mV, from seven pairs of control and PAE rats.

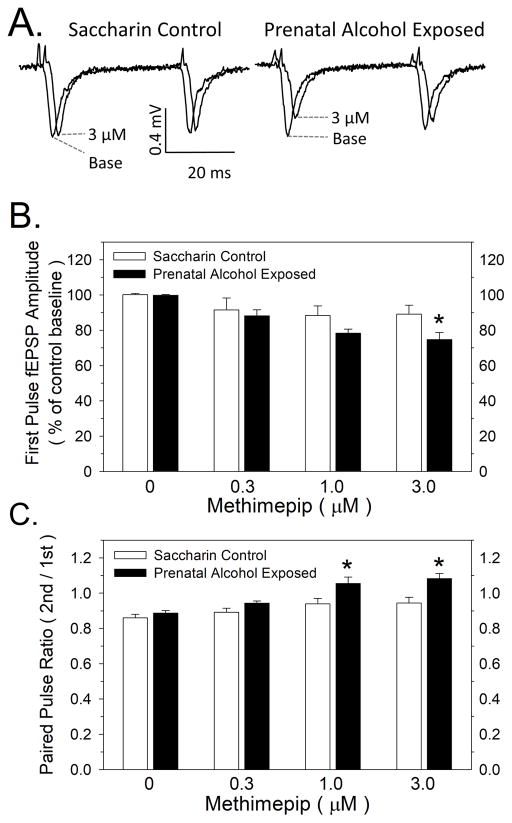

FIGURE 5.

Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) on histamine H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of fEPSP responses and paired-pulse ratio. 5A: Representative fEPSP traces evoked by pairs of pulses given at a 40 millisecond interpulse interval are shown at zero and 3 μM methimepip for control and PAE rats. 5B: Effect of PAE on methimepip inhibition of first-pulse fEPSP amplitude responses. Data bars represent the mean ± SEM first-pulse fEPSP amplitude, expressed as percent of saccharin control baseline responses, from seven pairs of control and PAE rats. Asterisks denote significantly greater inhibition in PAE rats compared to controls (* - p < 0.05). 5C: Effects of PAE on methimepip enhancement of the paired-pulse ratio. Data bars represent the mean ± SEM paired-pulse ratio, expressed as the second fEPSP pulse amplitude/first fEPSP pulse amplitude, in seven pairs of control and PAE rats. Asterisks denote a significantly higher PPR, reflecting a lower probability of glutamate release in PAE rats compared to controls (* - p < 0.05).

RESULTS

Voluntary Drinking Paradigm

Rat dams consumed an average of 1.98 ± 0.07 g/kg/day of ethanol throughout gestation, a level of consumption that produced a mean serum ethanol concentration of 60.8 + 5.8 mg/dL (Table 1) 45 minutes after the introduction of the drinking tubes, 30 minutes after the observed mean peak ethanol consumption time at 15 minutes (data not shown). This voluntary drinking paradigm did not affect maternal weight gain, litter size or offspring birth weight (Table 1).

Histamine H3 Receptor Binding Studies

We first characterized specific [3H]-A349821 binding to sagittal brain sections from untreated control rats. A349821 is a histamine H3 receptor antagonist that binds with similar affinity to H3 receptor iosforms (Witte et al., 2006). Figure 1A illustrates the distribution of total [3H]-A349821 binding to histamine H3 receptors in a sagittal section from an untreated rat brain. Histamine H3 receptors exist in relatively low densities throughout the rat brain. Thus, extended periods of film exposure (four months) are required, due to the low receptor density coupled with the use of a tritiated radioligand. A longer exposure period increases the film background measure leading to a corresponding reduction in the signal to noise ratio and limiting the number of discreet brain regions where we could reproducibly quantitate [3H]-A349821 binding. Nevertheless, specific [3H]-A349821 binding was heterogeneously distributed across the brain with relatively higher densities occurring in the caudate nucleus, intermediate levels in the middle and deep layers of the cerebral cortex and lower levels in the dentate gyrus (Figure 1A). As it was difficult to visualize specific [3H]-A349821 binding in the dentate gyrus at the lower radioligand concentrations used in the initial saturation of binding study, we used measurements of specific [3H]-A349821 binding in the medial frontal cortex to characterize the binding reaction (Figure 1B and 1C). Specific [3H]-A-349821 binding in medial frontal cortex of untreated control rats suggested that [3H]-A349821 bound to a single non-interacting population of binding sites with an apparent affinity constant of 11.7 nM and a Bmax of 0.324 fmoles/105 μm2 (Figure 1C).

We next examined whether PAE elevated the density of histamine H3 receptors in the dentate gyrus, as well as medial frontal cortex and the caudate nucleus. The quantity of donated radioligand remaining was not sufficient to conduct a full saturation of specific [3H]-A349821 receptor binding study in control and PAE rats. Thus, sagittal sections from both control and PAE rat offspring were incubated in the presence of either a “near Kd” (9 nM) or “near-saturating” (33.6 nM) concentration of [3H]-A349821, and H3 receptor binding site densities measured in the dentate gyrus, medial frontal cortex and caudate nucleus. No differences in specific [3H]-A349821 binding were noted between controls and PAE offspring at either radioligand incubation concentration in any of the three brain regions analyzed (Table 2).

Histamine H3 Receptor-Effector Coupling Studies

The specific [3H]-A349821 binding studies suggested that PAE does not increase histamine H3 receptor density (Table 2). We next examined whether PAE affected histamine H3 receptor-effector coupling by incubating brain sections with [35S]-GTPyS in the presence of the H3 agonist methimepip. Methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding displayed a qualitatively similar heterogeneous pattern of distribution in sagittal sections of rat brain (Figure 2A) as total [3H]-A349821 binding (Figure 1A). However, the agonist-stimulated signal coupled with the higher specific activity of [35S]-GTPγS yielded greater autoradiographic contrast, allowing the quantitation of histamine H3 receptor activity in additional regions, such as the cerebellar stratum moleculare, that were not readily discernable in autoradiograms of specific [3H]-A349821 binding.

In an initial study in control and PAE rats, a near-maximally effective concentration of methimepip (2 μM) was used to measure histamine H3 agonist-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding in ten different brain regions. Basal [35S-GTPγS binding was not different between the two prenatal treatment groups in any of the brain regions measured (data not shown). In control rats, methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was highest in medial frontal cortex, followed by intermediate levels in parietal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and caudate nucleus, and lower levels in dentate gyrus, cerebellum and the superior and inferior colliculi (Figure 2B). In contrast to specific [3H]-A349821 binding, methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was significantly elevated in the dentate gyrus, cerebellum and cortical regions of PAE rats compared to controls. H3 agonist-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS biding was not different in other subcortical brain regions.

A subsequent more-detailed agonist dose-response study, focused on the dentate gyrus, revealed that methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding increased above baseline over a roughly four orders of magnitude increase in methimepip concentration (Figure 3). A two-way ANOVA revealed significant effects of methimepip (F(1,15) = 90.3, p<0.001) and prenatal treatment group (F(1,15) = 31.4, p < 0.001) and no interaction between factors. At the apparent near-maximally effective agonist concentration of 5 μM methimepip, [35S]-GTPγS binding was 82% greater than basal [35S]-GTPγS binding in control offspring and 148% above basal binding in PAE offspring. A Student-Newman-Keuls pairwise multiple comparison analysis revealed that methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was significantly greater in PAE offspring compared to controls at methimepip concentrations at and above 0.1 μM (Figure 3). A kinetic analysis of the H3 agonist dose-response data using LIGAND indicated the presence of two agonist-sensitive subpopulations of histamine H3 receptors (Table 3). In control rats, the higher (kD1) and lower (kD2) affinity H3 receptor subpopulations each accounted for about one-half of the maximal agonist response, with apparent affinity constants of 0.868 and 422 nM respectively. In PAE rats, the apparent affinity constants were not significantly different from controls, nor was the agonist response to the higher affinity receptor population (Remax1) different. In contrast, the agonist response at the lower affinity population (Remax2) was significantly greater in PAE rats compared to controls (Table 3).

Effects of Methimepip on Glutamatergic Synaptic Transmission in the Dentate Gyrus

In the final set of experiments, we examined whether there was a physiological correlate to the observed PAE-induced increase in H3 receptor-effector coupling by conducting extracellular recording of granule cell responses to perforant path-evoked stimulation in slices of dentate gyrus. The recordings were performed in the same region of the dentate gyrus stratum moleculare as studied in the radiohistochemical experiments. Increased electrical stimulation of perforant path fibers in the medial layer of the dentate gyrus stratum moleculare resulted in increased fEPSP responses. However, as was observed previously in in vivo electrophysiological studies in control and PAE rats (Varaschin et al, 2010) PAE did not affect input/output responses dentate granule cells in slices (Figure 4).

The effects of methimepip and PAE on electrically-evoked fEPSP responses and on the PPR measure of glutamate release are depicted in Figure 5. Perfusing control slices with increasing concentrations of methimepip (0.3 – 3 μM) resulted in a modest decrease in fEPSP responses (Figure 5B). In contrast, methimepip produced greater inhibition of fEPSP responses in slices from PAE rat offspring. A two-way ANOVA indicated significant effects of both methimepip (F(1,3) = 8.08, p < 0.001) and prenatal treatment group (F(1,3) = 5.91, p = 0.019), but no significant interaction between factors. Post-hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between the control and PAE group only at the 3 μM concentration of methimepip (Figure 5B). Methimepip also dose-dependently increased the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) measure of glutamate release to a greater extent in PAE rats compared to controls (Figure 5C). Increasing the PPR is an index of a reduction in glutamate release probability. A two-way ANOVA indicated significant effects of both methimepip (F(1,3) = 16.3, p < 0.001) and prenatal treatment group (F(1,3) = 10.4, p < 0.001) but no significant interaction between factors. A post-hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between the control and PAE group at both the 1 μM and 3 μM concentrations of methimepip (Figure 5C).

DISCUSSION

The salient findings in this study are that prenatal exposure to moderate levels of alcohol increased methimepip-stimulated H3 receptor-effector coupling in dentate gyrus as well as enhanced methimepip’s inhibitory effects on first pulse fEPSPs and glutamate release. Further, the concentrations of methimepip that reduced fEPSP responses (Figure 5B) and heightened the PPR (Figure 5C) were similar to the methimepip concentrations that enhanced [35S]-GTPγS binding (Figure 3) measured in the same region within the superior blade of the dentate gyrus where the electrophysiological studies were performed. That methimepip-stimulated [35S]-GTPγS binding was also elevated in a variety of cortical regions and cerebellum of PAE rats compared to control (Figure 2B) suggests that PAE-induced elevation in histamine H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of glutamatergic neurotransmission may occur across large areas of the higher brain.

The mechanistic basis for elevated H3 receptor-effector coupling in PAE (Figure 2B) is currently unknown. Specific [3H]-A349821 binding data was not different between prenatal treatment groups (Table 2), suggesting that the total density of histamine H3 receptors in PAE rat brain is similar to controls (Table 2) and thus, not the basis for differential agonist-mediated responses. One possible explanation for heightened H3 receptor-effector coupling could be a PAE-induced alteration in the differential expression of H3 receptor isoforms expressed by entorhinal cortical neurons projecting to the dentate gyrus. At least three functional isoforms of histamine H3 receptors are expressed in rats (Morisset et al., 2001). These isoforms, which originate from alternative splicing of the H3 receptor gene, differ primarily in the length of the amino acid sequence within the third cytoplasmic loop of this transmembrane receptor protein. The truncated isoforms, identified in rat as the rH3B and rH3C isoforms, exhibit higher agonist affinity and lower intrinsic activity in comparison to the longer rH3A isoform which has lower agonist affinity and higher intrinsic activity (Bongers et al., 2007; Drutel et al., 2001). One reasoned speculation is that PAE may have shifted the predominant H3 receptor isoform expressed in entorhinal cortical neurons from the higher affinity less intrinsically active rH3B or rH3C isoforms to the lower affinity more intrinsically active rH3A isoform. Whereas there are, currently, no receptor subtype-selective H3 receptor drugs or antibodies to directly examine this question, one alternative approach was to conduct a detailed H3 agonist dose-response response study in control and PAE rats. While there was a small shift in the proportional agonist response between the higher and lower affinity receptor populations in PAE rats compared to controls (Table 3) which is consistent with speculation about a differential shift in the expression of H3 receptor isoforms, it is unclear whether a small shift in the differential expression of H3 receptor isoforms alone could account for the differential agonist responses (Figure 3, Figures 5B and 5C) observed in PAE rats.

One mechanism for increased intrinsic activity of the receptor-effector response could be an increase in the quantity of Gi/o protein levels in the perforant path nerve terminals. However, the observation that basal [35S]-GTPγS binding was not different between prenatal treatment groups (data not shown) does not support this idea. Another explanation could relate to the involvement of intracellular mechanisms that regulate G-protein coupling of metabotropic receptors to their effector mechanisms. While virtually nothing is known about these regulatory processes with respect to H3 receptors, there is evidence that various protein kinases and other factors regulate the coupling of another Gi/o protein-coupled receptor, namely the mGluR7 receptor (Sorensen et al., 2002), which also regulates the release of glutamate (Pelkey et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2008). This is an intriguing prospect relative to the differential receptor-effector coupling response in PAE rats given that some of these regulatory mechanisms target the third cytoplasmic loop of the mGluR7 receptor.

Whatever the mechanistic basis for elevated H3 receptor-effector coupling in PAE rats, this alteration provides one explanation for methimepip’s greater inhibitory effect on fEPSP responses and glutamate release (Figure 5B and 5C) in PAE rats. The possible mechanisms by which histamine H3 receptors inhibit glutamate release can be inferred based on evidence from studies of other presynaptic Gi/o-protein coupled receptors (reviewed by Betke et al., 2012). Upon activation, these G-proteins dissociate into Gi/o α and βγ subunits. The activated Gi/o α-subunit inhibits adenylyl-cyclase activity, leading to reduced cAMP levels and, consequentially, reduced protein kinase A (PKA) activity. As presynaptic voltage-gated calcium channels are a substrate for PKA, reduced phosphorylation of these channels could decrease neurotransmitter release. Additionally, the activated Gi/Go βγ-subunit directly inhibits voltage-gated calcium channels at axon terminals as well as soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) protein, leading to reduced synaptic vesicle exocytosis, further contributing to decreased neurotransmitter release. Histamine inhibits dentate gyrus granule cell excitability and glutamate release, probably by a direct blockade of voltage gated calcium channels by βγ subunits of Gi/o protein (Brown and Haas, 1999; Brown and Reymann, 1996). Here, it remains to be investigated whether or not PAE increases H3 receptor mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase and/or reduces voltage-gated calcium channel conductance as potential mechanisms for the observed differential effect on glutamate release.

Given prior studies demonstrating the inhibitory effects of H3 receptor agonists on glutamate release and dentate granule cell responses both in vitro (Brown and Reymann, 1996) and in vivo (Managhan-Vaughn et al., 1998; Varaschin et al., 2014), one somewhat unexpected result in the present study was the observation that methimepip produced only modest inhibition of fEPSP responses or glutamate release in control offspring (Figure 5B and 5C). Differences in slice electrophysiological approaches between laboratories may, in part, account for this apparent discrepancy. In the present study, one putative explanation for the different degrees of responses to methimepip by twelve-μm-thick sections used in radiohistochemical studies compared to 400-μm-thick slices used in physiological studies may be that higher agonist concentrations are required to penetrate slices to elicit responses of similar magnitude. Thus, it is possible that a greater degree of methimepip inhibition of fEPSP responses and glutamate release in control slices may have been observed had higher agonist concentrations been employed in this study. Nevertheless, the results indicate that PAE rats were more responsive to the inhibitory effects of methimepip than controls.

In summary, these in vitro studies provide the first report of a heightened histamine H3 receptor-mediated receptor-effector coupling associated with an inhibition of glutamate release from entorhinal cortical projections to the dorsal dentate gyrus of PAE rats compared to control offspring. This elevated inhibitory drive provides one mechanistic explanation for our prior observations of deficits in dentate gyrus LTP (Varaschin et al., 2010). However, given the complexity of the intrinsic and extrinsic regulation of dentate granule cell responsiveness, studies employing microinjections of a histamine H3 inverse agonist directly into the dentate gyrus will be required to further substantiate this interpretation. In addition, other putative mechanisms of H3 receptor inverse agonist/antagonist action in the dentate gyrus remain to be investigated. For example, the inhibition of H3 receptors on cholinergic nerve terminals facilitates acetylcholine release (Fox et al., 2005), which, in turn, could facilitate glutamatergic neurotransmission. In addition, H3 receptor antagonist-mediated inhibition of H3 autoreceptors located on histaminergic nerve terminals promotes histamine release (Arrang et al., 1983), which may facilitate excitation of glutamatergic neurons mediated via histamine postsynaptic H1 and H2 receptors (Haas, 1984; Selbach et al., 1997; Manahan-Vaughan et al., 1998). Further, histamine has been reported to have positive allosteric effects at the spermidine site on NMDA receptors (i.e.: Bekkers, 1993; Vorobjev et al., 1993). The extent to which each of these other mechanisms of H3 receptor inverse agonist/antagonist action may have contributed to an amelioration of a synaptic plasticity deficit in PAE offspring (Varaschin et al, 2010) is not known, but it is likely that the manner by which H3 receptor inverse agonists/antagonists enhance synaptic transmission at glutamatergic synapses in the central nervous system is complex, may be dose-dependent, and may also depend on level of arousal (Luo and Leung, 2010).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIAAA grants 1 P20 AA017068, 1 RO1 AA019884 and 1 P50 AA022534.

The authors have no conflict of interest related to the information communicated in this report.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Marion Cowart, Dr. Timothy Esbenshade, Dr. Tiffany Garrison, and Dr. Thomas Miller of Abbott Laboratories for their technical advice on the use of the [3H]-A349821 autoradiography methods. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Stefano Zucca and Ms. Aya Wadleigh in the Department of Neurosciences at the University of New Mexico for their advice on the electrophysiological studies of dentate gyrus

ABBREVIATIONS

- FASD

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

- fEPSP

field Excitatory Post-Synaptic Potential

- LTP

Long-term potentiation

- PAE

Prenatal Alcohol Exposure

- PPR

Paired-pulse ratio

- DG

Dentate gyrus

References

- Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Schwartz JC. Auto-inhibition of brain histamine release mediated by a novel class (H3) of histamine receptor. Nature. 1983;302:832–837. doi: 10.1038/302832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers JM. Enhancement by histamine of NMDA-mediated synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Science. 1993;261:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.8391168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betke KM, Wells CA, Hamm HE. GPCR mediated regulation of synaptic transmission. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;96:304–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers G, Krueger KM, Miller TR, Baranowski JL, Estvander BR, Witte DG, Strakhova MI, van Meer P, Bakker RA, Cowart MD, Hancock AA, Esbenshade TA, Leurs R. An 80-amino acid deletion in the third intracellular loop of a naturally occurring human histamine H3 isoform confers pharmacological differences and constitutive activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:888–898. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady ML, Allan AM, Caldwell KK. A limited access mouse model of prenatal alcohol exposure that produces long-lasting deficits in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:457–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brioni JD, Esbenshade TA, Garrison TR, Bitner SR, Cowart MD. Discovery of histamine H3 antagonists for the treatment of cognitive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:38–46. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.166876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Haas HL. On the mechanism of histaminergic inhibition of glutamate release in the rat dentate gyrus. J Physiol. 1999;515:777–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.777ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Reymann KG. Histamine H3 receptor-mediated depression of synaptic transmission in the dentate gyrus of the rat in vitro. J Physiol. 1996;496:175–184. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham J, Kilpatrick GJ. Histamine H3 receptors modulate the release of [3H]-acetylcholine from slices of rat entorhinal cortex: Evidence for the possible existence of H3 receptor subtypes. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;107:919–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb13386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa ET, Olivera DS, Meyer DA, Ferreira VMM, Soto EE, Frausto S, Browning MD, Savage DD, Valenzuela CF. Fetal alcohol exposure alters neurosteroid modulation of hippocampal NMDA receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38268–38274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drutel G, Peitsaro N, Karlstedt K, Wieland K, Smit MJ, Timmerman H, Panula P, Leurs R. Identification of rat H3 receptor isoforms with different brain expression and signaling properties. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbenshade TA, Browman KE, Bitner RS, Strakhova M, Cowart MD, Brioni JD. The histamine H3 receptor: An attractive target for the treatment of cognitive disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1166–1181. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GB, Esbenshade TA, Pan JB, Radek RJ, Krueger KM, Yao BB, Browman KE, Buckley MJ, Ballard ME, Komater VA, Miner H, Zhang M, Faghih R, Rueter LE, Bitner RS, Drescher KU, Wetter J, Marsh K, Lemaire M, Porsolt RD, Bennani YL, Sullivan JP, Cowart MD, Decker MW, Hancock AA. Pharmacological properties of ABT-239 [4-(2-{2-[(2R)-2-Methylpyrrolidinyl]ethyl}-benzofuran-5-yl)benzonitrile]: II. Neurophysiological characterization and broad preclinical efficacy in cognition and schizophrenia of a potent and selective histamine H3 receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:176–190. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo R, Frausto S, Wolff C, Caldwell KK, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Savage DD. Prenatal ethanol exposure reduces mGluR5 receptor number and function in the dentate gyrus of adult offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1587–1597. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000141815.21602.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garduno-Torres B, Trevino M, Gutierrez R, Arias-Montano JA. Pre-synaptic histamine H3 receptors regulate glutamate, but not GABA release in rat thalamus. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas HL. Histamine potentiates neuronal excitation by blocking a calcium-dependent potassium conductance. Agents Actions. 1984;14:534–537. doi: 10.1007/BF01973865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas HL, Sergeeva OA, Selbach O. Histamine in the nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1183–1241. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Goodlett CR, Hannigan JH. Animal models of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Impact of the social environment. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:200–208. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitbunnadaj R, Hashimoto T, Poli E, Zuiderveld OP, Menozzi A, Hidaka R, de Esch IJ, Bakker RA, Menge WM, Yamatodani A, Coruzzi G, Timmerman H, Leurs R. N-substituted piperidinyl alkyl imidazoles: Discovery of methimepip as a potent and selective histamine H3 receptor agonist. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2100–2107. doi: 10.1021/jm049475h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodituwakku PW. Neurocognitive profile in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15:218–224. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist E. The determination of ethyl alcohol in blood and tissues. Methods Biochem Anal. 1959;1:217–251. [Google Scholar]

- Luo T, Leung LS. Endogenous histamine facilitates long-term potentiation in the hippocampus during walking. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7845–7852. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1127-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mameli M, Zamudio PA, Carta M, Valenzuela CF. Developmentally-regulated actions of alcohol on hippocampal glutamatergic transmission. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8027–8036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2434-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan-Vaughan D, Reymann KG, Brown RE. In vivo electrophysiological investigations into the role of histamine in the dentate gyrus of the rat. Neuroscience. 1998;84:783–790. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson SN, Roesch SC, Glass L, Deweese BN, Coles CD, Kable JA, May PA, Kalberg WO, Sowell ER, Adnams CM, Jones KL, Riley EP CIFASD. Further development of a neurobehavioral profile of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:517–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Yokoyama T, Sumitani K, Kusaka T, Warita K, Matsumoto Y, Wang ZY, Wilce PA, Bedi KS, Itoh S, Takeuchi Y. Ethanol neurotoxicity and dentate gyrus development. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2008;48:110–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2008.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisset S, Sasse A, Gbahou F, Heron A, Ligneau X, Tardivel-Lacombe J, Schwartz JC, Arrang JM. The rat H3 receptor: Gene organization and multiple isoforms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:75–80. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolic K, Filipic S, Agbaba D, Stark H. Procognitive properties of drugs with single and multitargeting H3 receptor antagonist activities. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014;20:613–623. doi: 10.1111/cns.12279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton AR, Fontaine CJ, Christie BR. A comparison of the different animal models of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and their use in studying complex behaviors. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:93. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Lavezzari G, Racca C, Roche KW, McBain CJ. mGluR7 is a metaplastic switch controlling bidirectional plasticity of feedforward inhibition. Neuron. 2005;46:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Isaacson TV, Keidan GM, Eriqat C, Meiri KF, Savage DD, Allan AM. Prenatal ethanol exposure decreases GAP-43 phosphorylation and protein kinase C activity in the hippocampus of adult rat offspring. J Neurochem. 1998;71:2104–2111. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71052104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley EP. The long-term behavioral effects of prenatal alcohol exposure in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1990;14:670–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samudio-Ruiz SL, Allan AM, Valenzuela CF, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Caldwell KK. Prenatal ethanol exposure persistently impairs NMDA receptor-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in the mouse dentate gyrus. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1311–1323. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage DD, Cruz LL, Duran LM, Paxton LL. Prenatal ethanol exposure diminishes activity-dependent potentiation of amino acid neurotransmitter release in adult rat offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1771–1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage DD, Becher M, de la Torre AJ, Sutherland RJ. Dose-dependent effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on synaptic plasticity and learning in mature offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1752–1758. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000038265.52107.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage DD, Rosenberg MJ, Wolff CR, Akers KG, El-Emawy A, Staples MC, Varaschin RK, Wright CA, Seidel JL, Caldwell KK, Hamilton DA. Effects of a novel cognition-enhancing agent on fetal ethanol-induced learning deficits. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1793–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker E, Betz R, Gothert M. Histamine H3 receptor-medicated inhibition of serotonin release in the rat brain cortex. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1988;337:588–590. doi: 10.1007/BF00182737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker E, Fink K, Detzner M, Gothert M. Histamine inhibits dopamine release in the mouse striatum via presynaptic H3 receptors. J Neural Trans Gen Sect. 1993;93:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01244933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker E, Fink K, Hinterhaner M, Gothert M. Inhibition of noradrenaline release in the rat brain cortex via presynaptic H3 receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1989;340:633–638. doi: 10.1007/BF00717738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider ML, Moore CF, Adkins MM. The effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on behavior: Rodent and primate studies. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21:186–203. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9168-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selbach O, Brown RE, Haas HL. Long-term increase of hippocampal excitability by histamine and cyclic AMP. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1539–1548. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim LJ, Selley DE, Childers SR. In vitro autoradiography of receptor-activated G proteins in rat brain by agonist-stimulated guanylyl 5′-[gamma-[35S]thio]-trisphosphate binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7242–7246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen SD, Macek TA, Cai Z, Saugstad JA, Conn PJ. Dissociation of protein kinase-mediated regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 (mGluR7) interactions with calmodulin and regulation of mGluR7 function. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:1303–1312. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.6.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland RJ, McDonald RJ, Savage DD. Prenatal exposure to moderate levels of ethanol can have long-lasting effects on learning and memory of adult rat offspring. Psychobiology. 2000;28:532–539. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:2<232::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland RJ, McDonald RJ, Savage DD. Prenatal exposure to moderate levels of ethanol can have long-lasting effects on hippocampal synaptic plasticity in adult offspring. Hippocampus. 1997;7:232–238. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:2<232::AID-HIPO9>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titterness AK, Christie BR. Prenatal ethanol exposure enhances NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation in the adolescent female dentate gyrus. Hippocampus. 2012;22:69–81. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela CF, Morton RA, Diaz MR, Topper L. Does moderate drinking harm the fetal brain? Insights from animal models. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varaschin RK, Akers KG, Rosenberg MJ, Hamilton DA, Savage DD. Effects of the cognition-enhancing agent ABT-239 on fetal ethanol-induced deficits in dentate gyrus synaptic plasticity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:191–198. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.165027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varaschin RK, Rosenberg MJ, Hamilton DA, Savage DD. Differential effects of the histamine H(3) receptor agonist methimepip on dentate granule cell excitability, paired-pulse plasticity and long-term potentiation in prenatal alcohol-exposed rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:1902–1911. doi: 10.1111/acer.12430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorobjev VS, Sharonova IN, Walsh IB, Haas HL. Histamine potentiates N-methyl-D-aspartate responses in acutely isolated hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1993;11:837–844. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeber EJ, Savage DD, Sutherland RJ, Caldwell KK. Fear conditioning-induced alterations of phospholipase C-beta1a protein level and enzyme activity in rat hippocampal formation and medial frontal cortex. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2001;76:151–182. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte DG, Yao BB, Miller TR, Carr TL, Cassar S, Sharma R, Faghih R, Surber BW, Esbenshade TA, Hancock AA, Krueger KM. Detection of multiple H3 receptor affinity states utilizing [3H]A-349821, a novel, selective, non-imidazole histamine H3 receptor inverse agonist radioligand. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:657–670. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CS, Bertaso F, Eulenburg V, Lerner-Natoli M, Herin GA, Bauer L, Bockaert J, Fagni L, Betz H, Scheschonka A. Knock-in mice lacking the PDZ-ligand motif of mGluR7a show impaired PKC-dependent auto-inhibition of glutamate release, spatial working memory deficits, and increased susceptibility to pentylenetetrazol. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8604–8614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0628-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]