Abstract

Intestinal epithelial cells form a barrier that is critical in protecting the host from the hostile luminal environment. Previously, we showed that lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) receptor 1 regulates proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells, such that the absence of LPA1 mitigates the epithelial wound healing process. This study provides evidence that LPA1 is important for the maintenance of epithelial barrier integrity. The epithelial permeability, determined by fluorescently labeled dextran flux and transepithelial resistance, is increased in the intestine of mice with global deletion of Lpar1, Lpar1−/− (Lpa1−/−). Serum liposaccharide level and bacteria loads in the intestinal mucosa and peripheral organs were elevated in Lpa1−/− mice. Decreased claudin-4, caudin-7, and E-cadherin expression in Lpa1−/− mice further suggested defective apical junction integrity in these mice. Regulation of LPA1 expression in Caco-2 cells modulated epithelial permeability and the expression levels of junctional proteins. The increased epithelial permeability in Lpa1−/− mice correlated with increased susceptibility to an experimental model of colitis. This resulted in more severe inflammation and increased mortality compared with control mice. Treatment of Caco-2 cells with tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ significantly increased paracellular permeability, which was blocked by cotreatment with LPA, but not LPA1 knockdown cells. Similarly, orally given LPA blocked tumor necrosis factor–mediated intestinal barrier defect in mice. LPA1 plays a significant role in maintenance of epithelial barrier in the intestine via regulation of apical junction integrity.

The luminal surface of the gastrointestinal tract is lined with a monolayer of polarized epithelial cells that absorb nutrients and fluid. In addition to the absorptive functions, the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) form a physical and functional barrier separating the complex luminal milieu and the host.1 Epithelial cells are joined together by a highly organized apical junctional complex that includes tight junctions (TJs) and adherens junctions (AJs).2 The core of the apical junction is composed of transmembrane proteins forming a link between adjacent cells, thereby forming a barrier to paracellular diffusion of solutes and fluid. Defective intestinal epithelial barrier is characterized by an increase in intestinal permeability, allowing intestinal penetration of noxious substances present in the lumen, including bacteria, bacterial toxins, and digestive food products.3 Increased intestinal permeability is associated with chronic inflammatory diseases of the gut, including Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, and infectious diarrheal disease.4, 5 In addition, increased intestinal permeability induces inflammation in peripheral organs, contributing to the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, nephropathy, and autoimmune encephalomyelitis.6, 7, 8 On the other hand, the incidence of diabetes can be reduced by strengthening intestinal barrier function.9

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is a naturally occurring bioactive lipid, present in plasma, saliva, follicular fluid, and malignant effusion.10 LPA mediates a myriad of cellular effects through activation of at least six known G-protein–coupled receptors, LPA1 to LPA6.10 A body of evidence links LPA to chronic conditions, including cancer, inflammation, fibrosis, and atherosclerosis.10, 11 Emerging evidence demonstrates the effects of LPA in exacerbation of chronic pathological conditions in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Orally delivered LPA increased tumor burden, whereas the loss of LPA2 significantly decreased the progression of cancer in mouse models of familiar adenomatous polyposis– and colitis-associated cancer.12, 13 Inhibition of autotaxin, the enzyme generating extracellular LPA, by a small molecule decreased the severity of colitis in colitis model mice.14 However, recent studies have revealed that LPA-mediated signaling can also have protective effects in the GI tract. It is demonstrated that LPA regulates electrolytes and water movement in intestinal epithelial cells, potentially serving as an antidiarrheal agent.15, 16, 17 LPA induces cellular tension and cell surface fibronectin assembly, an important process in wound repair.18 Accordingly, LPA stimulates intestinal epithelial cell migration and proliferation and ameliorates epithelial damage in the trinitrobenzene model of colitis in rats.19 In addition, cabbage leaf–derived LPA promotes proliferation and migration of Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts; intragastric administration of LPA-rich Chinese medicine, antyu-san, is reported to be effective in the treatment of stress-induced ulcer in rats.20, 21 The GI tract expresses multiple LPA receptors. Of these receptors, LPA1 is the highest based on transcript expression.12 Mice with global deletion of Lpar1, Lpar1−/− (Lpa1−/−), experience perinatal lethality in 50% of newborns because of craniofacial dysmorphism and suckling defect, the latter resulting from defective olfaction.22 Surviving Lpa1−/− mice have similar food intake compared with wild-type (WT) littermates, indicating the absence of gross defect in the GI tract; however, Lpa1−/− mice are smaller compared with their WT siblings because of abnormal bone development.22, 23, 24 Despite the absence of GI tract defect in the absence of LPA1, the villi in the Lpa1−/− intestine are shortened compared with control, and the number of proliferating epithelial cells and the movement of these cells toward the luminal surface are decreased in Lpa1−/− mice.25 In addition, genetic ablation or pharmacologic inhibition of LPA1 impairs topical wound healing in the colon and delays the recovery from dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)–induced colitis, demonstrating the role of LPA1 in the epithelial repair process.25

However, it is not known if LPA1 plays a role in maintenance of intestinal epithelial barrier function. Herein, we report that Lpa1−/− mice have increased epithelial permeability in the intestine, which results in increased bacterial infiltration and inflammatory cytokine expression. The absence of LPA1 exacerbated DSS-induced colitis, whereas LPA protected mice from epithelial dysfunction induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. These results show that LPA1 contributes to the maintenance of intestinal epithelial barrier function.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Antibodies

LPA (18:1; 1-oleoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphate) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) and prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. For in vitro study, LPA was used at the final concentration of 1 μmol/L in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin, unless otherwise specified. An equal volume of PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin was added as a control. The following antibodies were purchased: rabbit anti–Ki-67 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); rabbit anti–claudin-2, anti–claudin-4, and anti–claudin-7 and rabbit anti-occludin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA); goat anti–E-cadherin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); rabbit anti-IgA (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL); rat anti-CD3 (Ebioscience, San Diego, CA); and mouse anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Cell Culture and Plasmids

Caco-2 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 15 mmol/L HEPES, and 1× nonessential amino acids. Caco-2 cells were transduced with lentiviral shRNA targeting LPA1 or scramble control (Sigma-Aldrich). For overexpression of LPA1, Caco-2 cells were transduced with lentiviral pCDH carrying human LPA1, as previously described.25 Lentiviral pCDH was used as a control. Lentiviral shRNA targeting phospholipase C (PLC)-β1 or PLC-β2 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Unless specified, cells transfected with lentivirus were selected by puromycin resistances to obtain stably transfected cells. Silencing of gene products was confirmed by RT-PCR.

Animals

Generation of Lpa1−/− mice has been previously reported.22 Lpa1+/− mice were crossbred to generate Lpa1+/+ (WT) and Lpa1−/− littermates, which were used in all studies. All data represent results of at least two independent series of experiments. Experiments with animals were performed under approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Atlanta Veterans Administration Medical Center and Emory University (Atlanta, GA) and in accordance with the NIH's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.26

In Vitro Permeability Measurement

Caco-2 cells were seeded on Transwell (Corning, Tewksbury, MA) and were cultured for 3 weeks for formation of a polarized epithelial monolayer. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) of the Caco-2 monolayer was measured using an epithelial V-Ω meter (World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL). Resistance of the Caco-2 cells on filter was calculated by subtracting the resistance of the membrane plus media from the resistance of the membrane plus media plus cells. Each Transwell was measured in triplicate, and the average value was taken. This value was then multiplied by the area of the Transwell membrane (0.33 cm2) to obtain a final value in Ω × cm2. To measure permeability across the monolayer, Caco-2 cells on Transwells were washed with PBS twice. Fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran, 4 kDa (FD-4; Sigma-Aldrich) in Hanks' balanced salt solution was added to the apical side of the cells at 10 μmol/L concentration. Three hours later, Hanks' balanced salt solution on the basolateral side was collected and measured for fluorescence at 485/528 nm (excitation/emission) in a microplate fluorescence reader.

Intestinal Permeability in Vivo

Proximal colonic mucosal sheets of WT and Lpa1−/− littermates were collected, stripped of muscular layer, and mounted in dual-channel Ussing chambers (U-2500; Warner Instruments, Inc., Hamden, CT), and the electrical resistance (Ω × cm2) was determined, as previously described.27 Intestinal permeability was assessed in vivo using FD-4 as a mucosal tracer flux marker. FD-4 in PBS (50 mg/mL) was administered by gastric gavage at a final dose of 40 mg/100 g body weight. Four hours later, mice were euthanized and blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture. Blood was centrifuged at 4°C, 10,000 × g, for 5 minutes, and serum was diluted in an equal volume of PBS. Fluorescence intensity in the serum was measured at an excitation of 485 nm and an emission of 525 nm (485/528 nm) using a Synergy2 (BioTek, Winooski, VT) plate reader. Concentrations of FD-4 were tabulated against a standard curve.

Animal Treatment

Male mice, aged 9 weeks, were pretreated with either LPA (150 μL of 300 μmol/L stock) or PBS by gavage daily for 3 days. On day 3, mice were given an i.p. injection of TNF-α (4 μg) or PBS. All mice were then gavaged with FD-4, and intestinal permeability was determined, as described in Intestinal Permeability in Vivo.

Measurement of Serum LPS

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the serum was determined by using LPS enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Kamila Biomedical Co, Seattle, WA).

Cecal Microbial Profiling by Quantitative RT-PCR

Mice were euthanized with isoflurane, and the intestines were removed under sterile conditions. The contents of the cecum were collected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Bacterial total DNA (genomic DNA) was isolated using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Frederick, MD). Primer design and PCR amplification were performed on a Real Plex4 RealTime System (Eppendof, Hauppauge, NY), as previously published by Larmonier et al.28

DSS-Induced Colitis

To induce experimental colitis, 8- to 10-week-old male mice (n = 12 per strain) were permitted free access to 2% DSS (w/v; mol. wt., 36,000 to 50,000; Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) in drinking water for 7 days in acute colitis experiments. Half of the mice were euthanized at the end of DSS treatment, whereas the remaining half were given normal water for the next 7 days to recover. Body weight of each mouse was measured and recorded daily. Assessment of stool consistency and the presence of occult blood by a guaiac test (Hemoccult Sensa; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) were determined daily for each mouse. Each parameter was assigned a score of stool consistency and bleeding, as previously described.13, 29 The diarrheal index was measured using fecal consistency (0, normal; 1, soft feces; 2, mild diarrhea; and 3, severe diarrhea). Scoring for occult blood was as follows: 0, normal; 1, positive hemoccult test result; 2, visible blood in the stool; and 3, rectal bleeding. Scoring for body weight change was as follows: 0 for <1%, 1 for 1% to 5%, 2 for 6% to 10%, 3 for 11% to 20%, and 4 for >20% loss. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation on day 7 or 14. Neutrophil migration was determined by using a myeloperoxidase activity assay kit (Abcam).

Histology

For each animal, histological examination was performed on three samples of the distal colon. Histological parameters were quantified in a blinded manner (S.L. and P.H.) using the scores previously published.30 Three independent parameters were measured: severity of inflammation (0 to 3, where 0 indicates none; 1, slight; 2, moderate; and 3, severe); depth of injury (0 to 3, where 0 indicates none; 1, mucosal; 2, mucosal and submucosal; and 3, transmural); and crypt damage (0 to 4, where 0 indicates none; 1, basal one-third damaged; 2, basal two-thirds damaged; 3, only surface epithelium intact; and 4, entire crypt and epithelium lost). The score of each parameter was multiplied by a factor reflecting the percentage of tissue involvement (×1, 0% to 25%; ×2, 26% to 50%; ×3, 51% to 75%; and ×4, 76% to 100%), and these values were summed to obtain a total score.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining of intestinal tissues was performed, as described previously.13 Briefly, mouse colonic tissues embedded in paraffin were cut into sections (5 μm thick). Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, and antigen unmasking was performed through microwave treatment in a citrate buffer. A Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA) Avidin/Biotin Blocking kit was used in conjunction with a blocking buffer to reduce background and nonspecific secondary antibody binding. Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight. Detection of primary antibodies and color development were done using the Dako k6090 kit (Agilent, Carpinteria, CA). Sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and covered with a coverslip. Images were acquired using an Axioskop 2 plus microscope (Zeiss, Thorwood, NY) equipped with an AxioCam MRc5 charge-coupled device camera (Zeiss).

Confocal Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Intestinal tissues were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek; Sakura, Torrance, CA) and were divided into sections, as previously described.31 The fluorescence staining procedures were described before.31 Specimens were observed under a Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

Electron Microscopy

Mouse intestinal tissues were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Samples were then washed with the same buffer and were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide post-fixed in 1% buffered osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series to 100%, and embedded in Eponate 12 resin (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA). Ultrathin sections (70 to 80 nm thick) were cut on a Leica UC6rt ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems) and counterstained with 5% aqueous uranyl acetate and 2% lead citrate. Sections were examined on a JEOL JEM-1400 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a Gatan US1000 charge-coupled device camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA).

Western Immunoblot

Western blotting was performed, as previously described.25 Mouse mucosal tissues were lysed for 30 minutes at 4°C in lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 10% glycerol, 20 mmol/L tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 2.5 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% aprotinin, and 100 μmol/L NaVO3. The lysates were centrifuged, and samples were processed for Western blotting. Western blots were quantified using ImageJ software version 1.51k (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij).

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from colonic mucosa of Lpa1−/− mice and WT littermates using an RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). cDNA synthesis was performed using 0.2 μg of RNA and the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative PCRs were performed using SYBR qPCR Premix (Biorad, Hercules, CA), as previously described.13 Expression levels were determined in triplicate per sample and normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Primers used were previously reported.13

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by a 2-tailed unpaired t-test or analysis of variance. Overall survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier methods, and differences were evaluated with the log-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

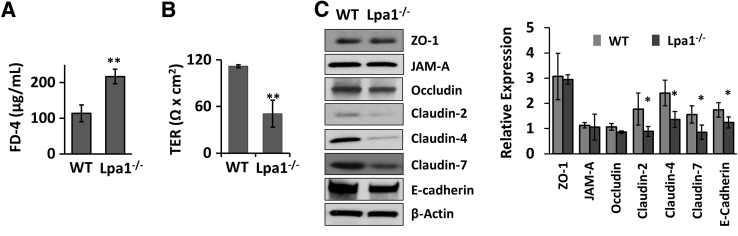

LPA1 Deficiency Results in Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction

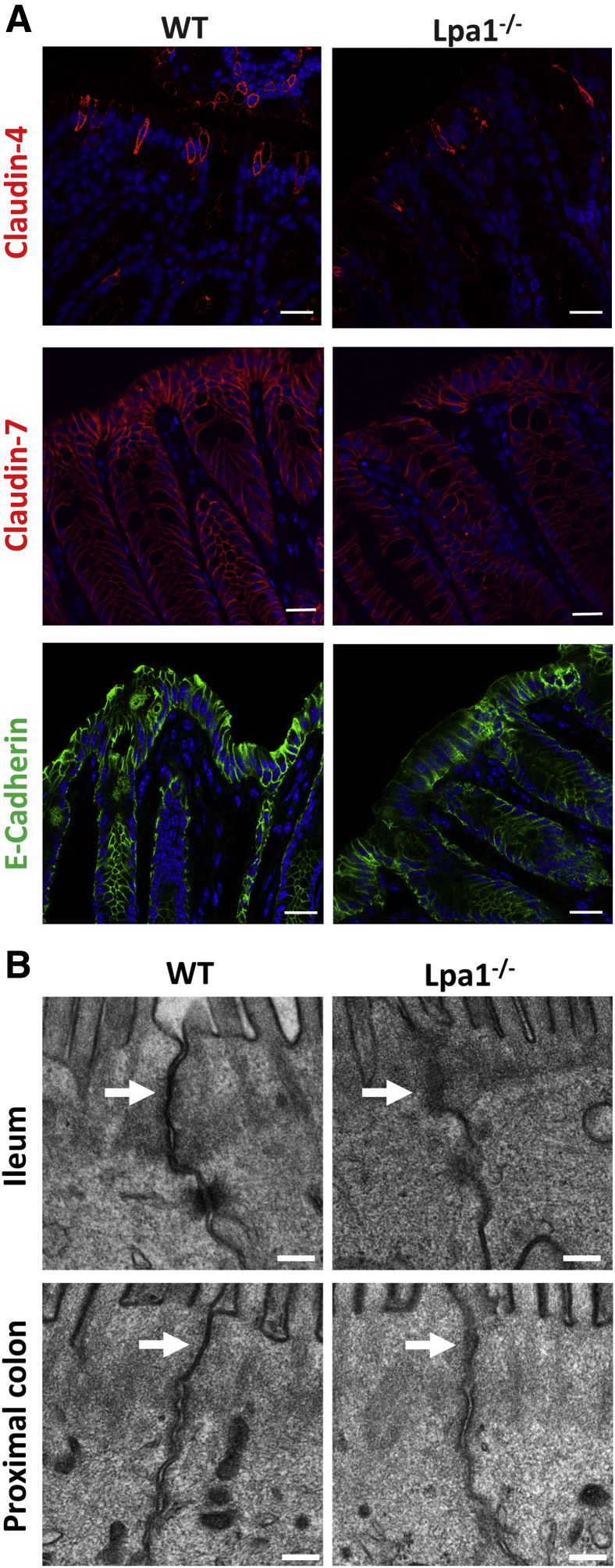

To assess whether the loss of LPA1 alters epithelial permeability in mouse intestine, intestinal permeability was determined in vivo by oral gavage of fluorescently labeled dextran, FD-4, in WT and Lpa1−/− mice. The measurement of the fluorescence levels in the serum revealed that FD-4 flux across the intestine was significantly elevated in Lpa1−/− mice compared with control mice (Figure 1A), indicating that intestinal epithelial permeability is increased in the absence of LPA1. The finding from FD-4 flux was corroborated by the TER measurement of isolated colonic tissues. TER across Lpa1−/− colonic tissues was significantly lower compared with WT colonic tissues (Figure 1B). Because the apical junctional integrity is a determinant of epithelial permeability, TJ and AJ protein expression was determined in WT and Lpa1−/− colon by Western blotting. Decreased expression levels of claudin-4, claudin-7, and E-cadherin were observed in Lpa1−/− mice, although the expression levels of zonula occludens protein 1 (ZO1), junctional adherens protein-A (JAM-A), and occludin were not significantly different (Figure 1C). Interestingly, claudin-2, which is often associated with leaky epithelia, was also decreased in Lpa1−/− mice.32 In line with the Western blots, immunofluorescence staining of Lpa1−/− colonic tissues showed decreased fluorescence signals of claudin-4, claudin-7, and E-cadherin in Lpa1−/− mouse colon (Figure 2A). Interaction with the cortical actin cytoskeleton represents a crucial mechanism that regulates the integrity and remodeling of epithelial junctions.33 LPA is a potent activator of Rho GTPase, which modulates actin dynamics, and LPA1 stimulates IEC migration by activation of Rac and actin cytoskeleton.25, 34 However, comparing perijunctional actin cytoskeleton in vivo and in vitro did not result in significant differences in actin cytoskeleton between WT and Lpa1−/− colonic sections as well as Caco-2 cells with or without LPA1 knockdown (Supplemental Figure S1). To further examine the change in the apical junction morphology resulting from the absence of LPA1, the ultrastructure of the apical junctions was evaluated in control and Lpa1−/− mouse intestine by electron microscopy. Intestinal epithelia from control mice showed the characteristic fusion points or kisses of adjacent membrane that define the tight junction (Figure 2B).2 This appearance was less distinct in Lpa1−/− mice, suggesting perturbation of the junctional complex in these mice.

Figure 1.

Increased intestinal permeability in Lpa1−/− mice. A: WT and Lpa1−/− mice were orally gavaged with fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran, 4 kDa (FD-4). Four hours later, FD-4 levels in the serum were determined. B: Colonic sections of WT and Lpa1−/− mice were mounted on Ussing chambers, and transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) across the colonic tissues was determined, as described in Materials and Methods. C: Left panel: Representative Western blots of tight junction and adherens junction proteins in colonic lysates of WT and Lpa1−/− mice. Right panel: Quantifications of at least three independent experiments. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A–C). n = 4 (A and B). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT. JAM-A, junctional adherens protein-A; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1; ZAM-A, junctional adhesion molecule-A.

Figure 2.

The loss of LPA1 affects junctional protein expression and apical junction structure. A: Immunofluorescence images of claudin-4, claudin-7, and E-cadherin expression on the colon of WT and Lpa1−/− mice. DAPI (blue) staining was used to counterstain nuclei. B: Electron micrographs of intestinal epithelial cells from distal ileum (top row) and proximal colon (bottom row) of WT and Lpa1−/− mice show the apical junction structures. Arrows point to kisses of tight junction. Scale bars: 20 μm (A); 0.2 μm (B).

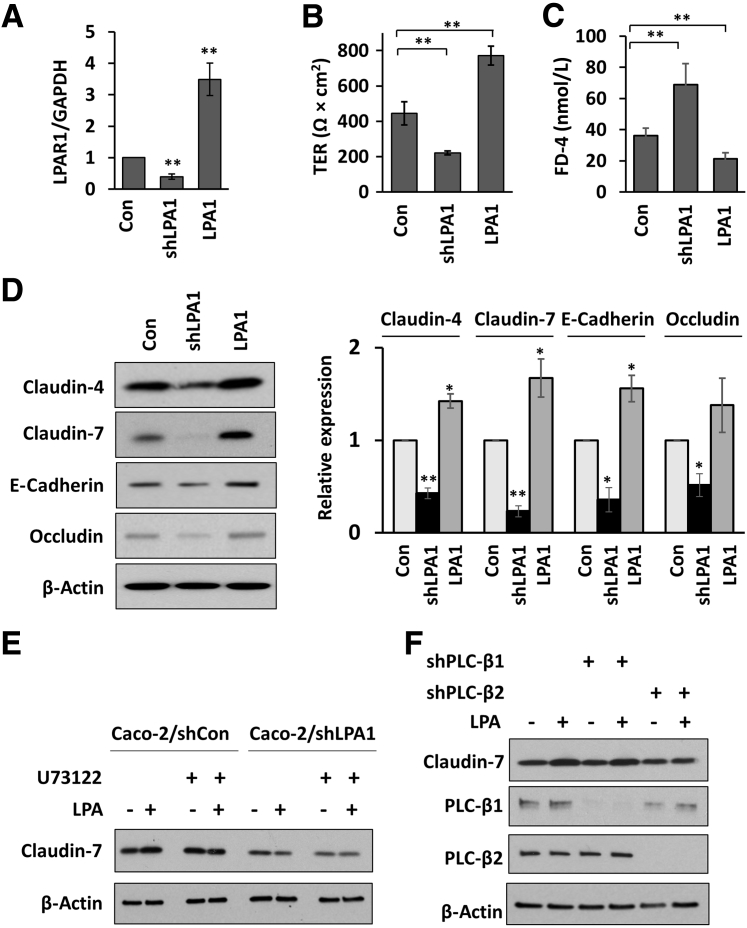

Because Lpa1−/− mice have global deletion of LPA1, it was investigated whether loss of LPA1 in epithelial cells compromises the epithelial permeability and AJ and TJ protein expression. Human colonic epithelial Caco-2 cells were transfected to have either knockdown of endogenous LPA1 or overexpression of human LPA1. The relative LPA1 mRNA levels are shown in Figure 3A. Epithelial barrier integrity was assessed by measuring TER of cells grown on Transwells. Consistent with the in vivo data, knockdown of LPA1 lowered TER, whereas overexpression increased TER (Figure 3B). In addition, FD-4 flux was inversely dependent on LPA1 expression (Figure 3C). Decreased expression of claudin-4, claudin-7, E-cadherin, and occludin was also observed in LPA1 knockdown cells, whereas overexpression of LPA1 increased their expression (Figure 3D). Although occludin expression appeared elevated in LPA1-overexpressing cells, the difference was not statistically significant compared with control cells.

Figure 3.

Effect of LPA1 expression on epithelial permeability in Caco-2 cells. A: Caco-2 cells were transfected to either knock down [lentiviral shRNA targeting LPA1 (shLPA1)] or overexpress LPA1 (LPA1). LPA1 mRNA levels were determined and expressed relative to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA levels. B: Transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) across monolayers of Caco-2 cells grown on Transwells for 21 days was determined. C: Fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran, 4 kDa (FD-4), was applied to the apical compartment of Caco-2 monolayers, and FD-4 concentrations in the bottom compartment were determined 3 hours later. D: Western blot analysis to determine the expression levels of claudin-4, claudin-7, E-cadherin, and occludin in control Caco-2, Caco-2/shLPA1, and Caco-2/LPA1 cells. Left panel: Representative Western blots of three independent experiments are shown. Right panel: Quantification of protein bands normalized to β-actin expression. E: Caco-2 cells transfected with lentiviral shRNA targeting scramble control (shCon) or shLPA1 were treated with LPA in the presence or absence of U73122. Claudin-7 expression was determined by Western blotting. Representative Western blots of three independent experiments are shown. F: Claudin-7 expression was determined in Caco-2 cells transfected with shCon, shPLC-β1, or shPLC-β2. Knockdown of PLC-β1 or PLC-β2. Representative Western blots of three independent experiments are shown. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A–D). n = 6 (A–C); n = 3 (D). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus control. Con, control; LPA1, LPA receptor 1.

LPA1-dependent IEC signaling is mediated via PLC-β1 and PLC-β2.25 To examine a potential role of PLC-β in LPA1-dependent regulation of junctional proteins, the effect of the PLC inhibitor U73122 on claudin-7 expression was determined. LPA alone increased the expression of claudin-7 in control transfected Caco-2 cells, but not in LPA1 knocked down Caco-2 cells (Figure 3E). More important, pretreatment with U73122 abolished LPA-mediated increased claudin-7 expression. To determine specific roles of PLC-β1 and PLC-β2 in this regulation, Caco-2 cells were transfected to knock down PLC-β1 or PLC-β2. Knockdown of PLC-β2, but not of PLC-β1, ablated LPA-dependent regulation of claudin-7 (Figure 3F), demonstrating that LPA1 regulates claudin-7 expression via PLC-β2.

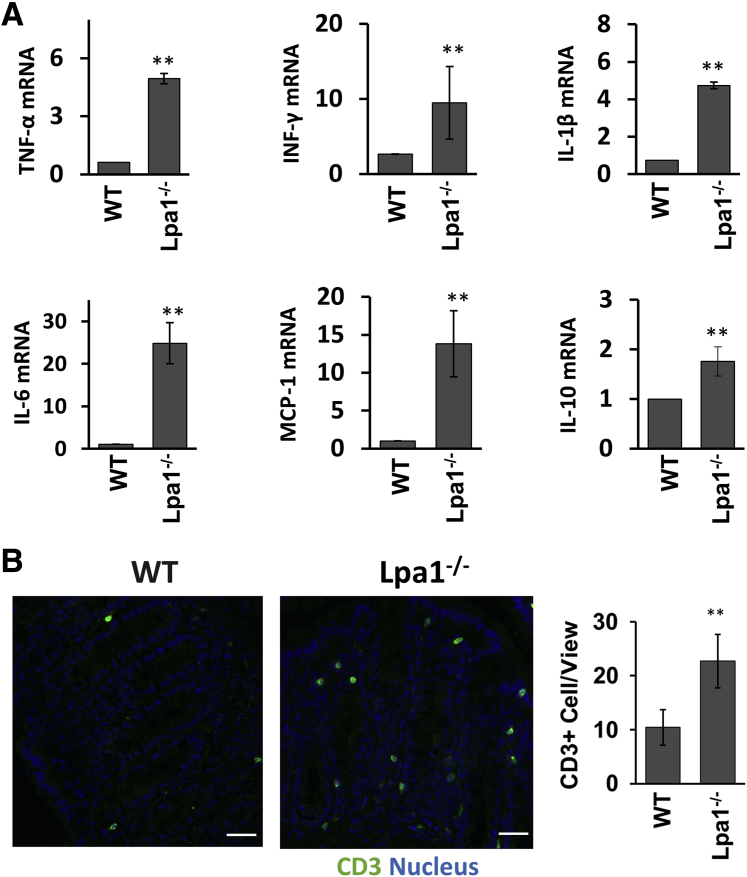

Increased Cytokine Expression and Bacterial Infiltration in Lpa1−/− Mice

Defective intestinal epithelia are often a cause of chronic inflammation.4, 5 Given the epithelial barrier dysfunction in Lpa1−/− mice, the expression levels of proinflammatory cytokine were determined in mouse mucosa by RT-PCR. In keeping with increased epithelial permeability, TNF-α, interferon (INF)-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and IL-10 mRNA levels were elevated in Lpa1−/− mouse colon (Figure 4A). The change in basal inflammation levels in Lpa1−/− mice was corroborated by increased T-cell distribution, determined by immunofluorescence staining of CD3 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Analysis of cytokine expression in Lpa1−/− mouse intestine. A: Expression levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (INF)-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) mRNA were determined and normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA levels. Data are presented as fold changes relative to the levels in WT mice. B: Left and middle panels: Representative immunofluorescence images of CD3 staining (green) in WT and Lpa1−/− colonic sections. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Right panel: Numbers of CD3+ cells were quantified by counting 20 fields of vision per mouse. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A and B). n = 5 (A and B). ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT. Scale bars = 30 μm (B).

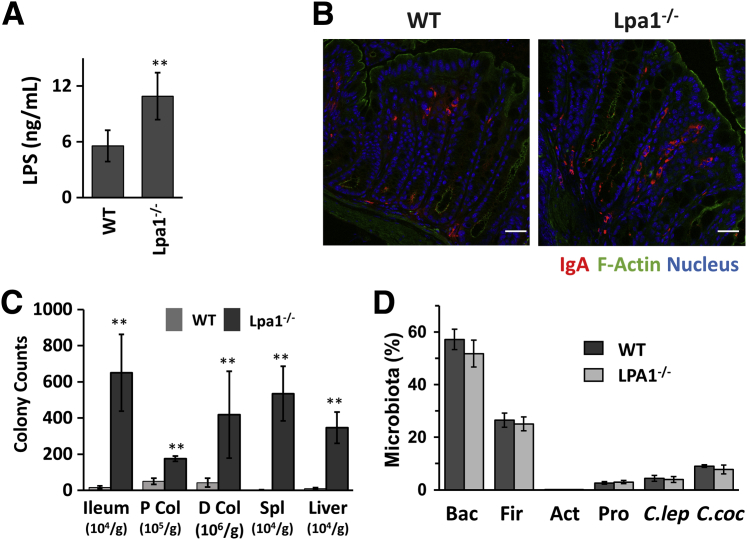

Aberrant intestinal epithelial barrier allows infiltration of microorganisms and their products into the mucosa, potentially eliciting inflammatory responses. Determination of serum LPS levels revealed doubling of serum LPS concentrations in Lpa1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Figure 5A), demonstrating that defective epithelial barrier in these mice permits increased penetration of microbial products. A notable response that follows the gut microbial colonization is the production of IgA, which neutralizes toxins and pathogenic microbes.35 Consistent with the increased LPS level, there was an increase in IgA production in the colonic mucosa of Lpa1−/− mice (Figure 5B). To further evaluate if the increased epithelial permeability in Lpa1−/− mice permits bacterial entrance into the body more readily, the bacterial loads were compared between WT and Lpa1−/− mice. The ileum and the proximal and distal colon of mice were homogenized, and serial dilutions of the homogenates were plated on agar overnight. A significant increase in bacterial counts was observed in ileal and colonic lysates of Lpa1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Figure 5C). Moreover, bacterial counts were also increased in the liver and spleen of Lpa1−/− mice, indicating that dissemination of bacteria to peripheral organs was greater in Lpa1−/− mice.

Figure 5.

Increased lipopolysaccharide (LPS) levels in Lpa1−/− mice. A: Serum LPS levels were determined in WT and Lpa1−/− mice. B: Confocal immunofluorescence images of IgA (red) in WT and Lpa1−/− colon. F-actin, green; nuclei, blue. C: Bacterial loads in the ileum, proximal colon (P Col), distal colon (D Col), spleen (Spl), and liver of WT and Lpa1−/− mice were determined. D: Microbiota in the cecum contents of WT and Lpa1−/− mice were analyzed by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A, C, and D). n = 6 (A); n = 5 (C); n = 4 (D). ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT. Scale bars = 30 μm (B). Act, actinobacteria; Bac, bacteriodetes; C.coc, Clostridium coccoides; C.lep, Clostridium leptum; Fir, fimicutes; Pro, proteobacteria.

Gene knockout in rodents is known to cause dysbiosis, which alters the gut bacteria and host interaction.36 Hence, the microbial compositions were compared in the cecum contents of WT and Lpa1−/− mice to determine whether a change in the microbiota-host interaction may contribute to the increased bacterial invasion in Lpa1−/− mice. Analysis of cecal contents showed that there was no difference in microbiota composition between these two strains (Figure 5D). Therefore, the increased bacterial load in Lpa1−/− mice was not because of a change in the gut microbiota but was rather a result of defective intestinal epithelial permeability permitting bacterial infiltration.

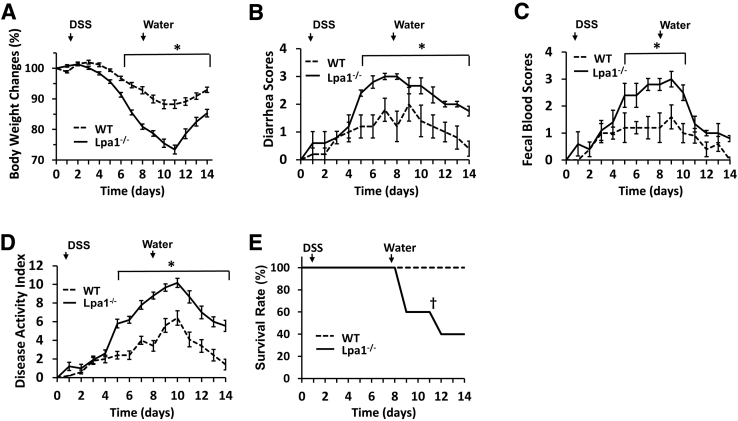

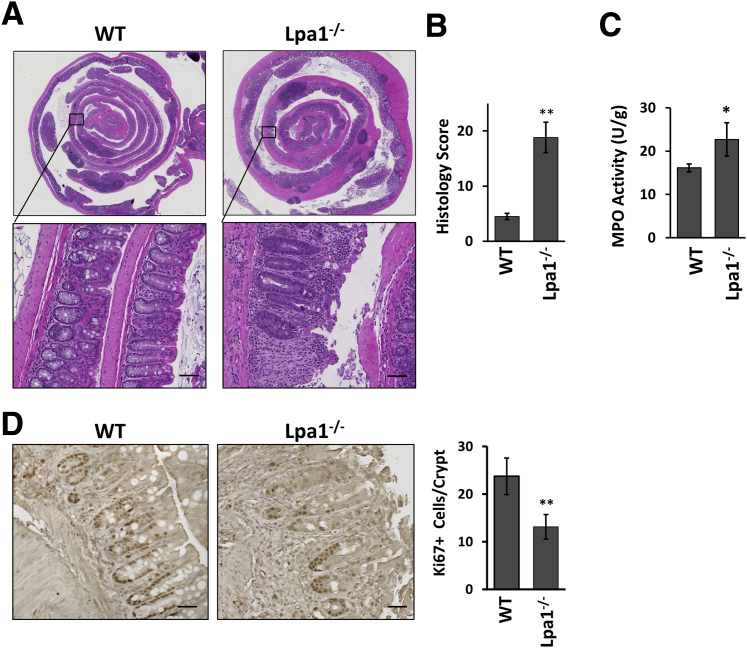

LPA1 Deficiency Aggravates DSS-Induced Colitis

Given the increased epithelial permeability, it was examined whether Lpa1−/− mice respond differently to an inflammatory insult. To this end, Lpa1−/− and WT mice were challenged with DSS. During the DSS treatment, Lpa1−/− mice showed more severe inflammation, as evidenced by greater clinical disease indexes that measure body weight loss, the presence of occult blood, and diarrhea (Figure 6, A–D). On day 14, inflammation in WT mice was largely subdued on the basis of the low disease activities. In contrast, disease activity indexes remained elevated in Lpa1−/− mice, suggesting the persistence of inflammation in these mice. Moreover, more than a half of the Lpa1−/− mice died or needed to be euthanized compared with WT mice, which all survived (Figure 6E). Histologic analysis revealed increased levels of epithelial erosion, crypt damage, and immune cell infiltration in Lpa1−/− mice than WT controls (Figure 7, A and B). Consistently, neutrophil migration assayed by myeloperoxidase activity was significantly greater in Lpa1−/− colon (Figure 7C). LPA1 plays a critical role in IEC proliferation and migration.25 Labeling of colonic sections on day 7 of DSS treatment with anti–Ki-67 antibody revealed decreased numbers of proliferating cells in the crypts adjacent to inflamed regions in Lpa1−/− mice compared with WT colon (Figure 7D), suggesting that epithelial proliferation is compromised in Lpa1−/− mice.

Figure 6.

Increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)–induced colitis by Lpa1−/− mice. WT and Lpa1−/− mice were given 2% DSS for 7 days, followed by 7 days of recovery. A–C: Each day, the mice were weighed (A), and their stools were collected to determine the diarrhea scores (B) and hemoccult scores (C), as described in Materials and Methods. D: Mean disease activity indexes are shown. E: Overall survival of WT and Lpa1−/− mice was determined during DSS treatment and recovery. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A–E). n = 12 per group (A–E). ∗P < 0.05; †P < 0.05 versus WT.

Figure 7.

Increased mucosal damage in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)–treated Lpa1−/− mice. A: Representative images of Swiss roll mounts of whole mouse colons collected from WT and Lpa1−/− mice that were given 2% DSS for 7 days. Bottom panels show magnified views of the boxed areas in the top panels. B: Histologic damage index scores from Swiss roll mounts of colons after 7 days of DSS treatment. C: Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activities were determined in the colons of WT and Lpa1−/− mice on day 7 of DSS treatment. D: Left and middle panels: Ki-67–stained mouse colonic sections on day 7 of DSS treatment. Right panel: Quantification of Ki-67 cells per crypt by counting >30 crypts per mouse. Data are expressed as means ± SD (B–D). n = 6 per group (B); n = 4 (C and D). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus WT. Scale bars: 50 μm (A); 30 μm (D).

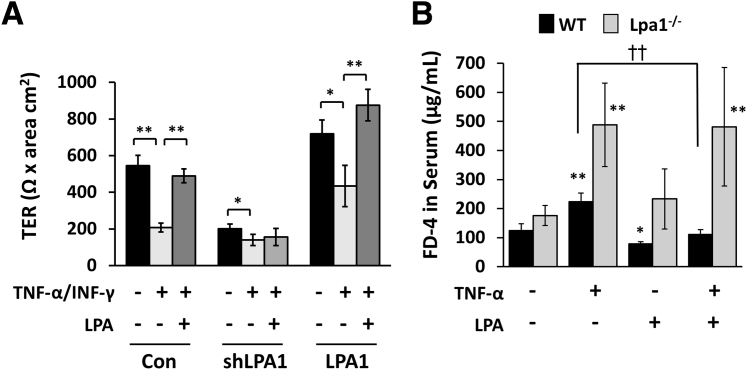

LPA Protects from TNF-Induced Barrier Dysfunction

Lines of evidence show that proinflammatory cytokines, including INF-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β, disrupt intestinal epithelial barrier function and contribute to mucosal inflammation.37, 38, 39 Therefore, it was determined if activation of LPA1 protects intestinal epithelial cells from barrier dysfunction induced by TNF-α. Hence, Caco-2 cell monolayer cultures on Transwells were treated with TNF-α and INF-γ together for 24 hours, which resulted in a significant decrease in TER (Figure 8A). The inhibitory effects of TNF-α/INF-γ were observed in both LPA1-overexpressing and knockdown cells. However, the effect of TNF-α/INF-γ treatment in Caco-2/lentiviral shRNA targeting LPA1 cells was relatively small because of the lower basal TER in these cells. To assess a protective effect of LPA, monolayers were cotreated with TNF-α/INF-γ and LPA. In Caco-2 and Caco-2/LPA1 cells, cotreatment with LPA prevented the decrease in TER. In contrast, the restoration of TER by LPA was absent in Caco-2/lentiviral shRNA targeting LPA1 cells. These results demonstrate that LPA prevents epithelial barrier dysregulation via activation of LPA1.

Figure 8.

Effects of LPA on epithelial dysfunction induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. A: Caco-2 monolayers were treated with TNF-α and interferon (INF)-γ in the presence or absence of LPA. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) was determined across the monolayers. B: WT and Lpa1−/− mice were gavaged with LPA or phosphate-buffered saline for 3 days. Mice were then given an i.p. injection of TNF-α and oral administration of fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran, 4 kDa (FD-4). Serum FD-4 levels were determined 4 hours later. Data are expressed as means ± SD (A and B). n ≥ 3 (A); n = 3 (B). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus untreated mice of the same genotype; ††P < 0.01. Con, control; shLPA1, lentiviral shRNA targeting LPA1.

The protective effect of LPA was evaluated in vivo from TNF-α–mediated barrier dysfunction. To this end, mice were pretreated daily for 3 days by oral gavage of LPA or PBS. A half of the PBS- or LPA-treated mice were given an i.p. injection of TNF-α, and epithelial permeability was determined using FD-4. As shown previously,39 TNF-α significantly increased the intestinal permeability in both the WT and Lpa1−/− mice, although the effect was greater in Lpa1−/− mice (Figure 8B). Compared with untreated control mice, WT mice that received oral administration of LPA had decreased paracellular flux, demonstrating that LPA augments basal intestinal barrier function. However, the effect of LPA on the FD-4 flux in Lpa1−/− mice was not significant. More important, pretreatment with LPA prevented TNF-α–induced barrier dysfunction in WT, but not in Lpa1−/−, mice. Together, these results demonstrate that LPA maintains intestinal epithelial integrity via LPA1 by augmenting epithelial barrier function.

Discussion

LPA1 stimulates intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo.25 The absence of LPA1 causes decreased proliferation and migration of IECs toward the luminal surface in both small intestine and colon. This process is critical for replacement of exfoliated IECs at the luminal surface and continual maintenance of the epithelial lining in the intestinal tract.25 IECs form a physical barrier, and defective barrier function is associated with increased luminal antigen leakage and the development of chronic inflammation.4, 5 The current study reveals an additional role of LPA1 in maintaining epithelial barrier function and protecting epithelium from cytokine-induced dysfunction. Aberrant LPA1 signaling increases intestinal epithelial permeability, with decreased expression of AJ proteins in Lpa1−/− mouse intestine. Lpa1−/− mice have increased intestinal permeability, accompanied by decreased expression of claudin-4, claudin-7, and E-cadherin. Surprisingly, claudin-2, which is highly expressed in leaky epithelia, was also decreased in Lpa1−/− mice.32 Although claudin-2 is a cation-selective channel associated with leaky epithelia,40 it was reported that targeted colonic claudin-2 expression renders resistance to epithelial injury and induces immune suppression, such that the decreased claudin-2 may further destabilize the innate immunity in Lpa1−/− mice.41 Moreover, claudin-2 is expressed in the crypt epithelial cells as opposed to claudin-4 and claudin-7, which are expressed primarily in the surface intestinal epithelium.42 Hence, what effects the decreased claudin-2 expression in the absence of LPA1 exert on the barrier function and immune homeostasis remain unclear. Because LPA1 is absent in all tissues in Lpa1−/− mice, the effect of LPA1 deletion was evaluated in Caco-2 cells. The in vitro study using Caco-2 cells provided direct evidence that the epithelial permeability is dependent on expression of LPA1. Knockdown of LPA1 significantly increased the paracellular permeability in the Caco-2 monolayer, whereas overexpression had an opposite effect. LPA is a normal constituent of serum,43 and addition of extracelluar LPA to Caco-2 cells cultured in full media did not significantly affect the basal epithelial function. The attempt to serum starve Caco-2 cells before LPA treatment was futile because serum starvation, or even incubation of Caco-2 cells in delipidated serum, significantly decreased TER, indicating general loss of Caco-2 cell polarity under these conditions.

Because LPA is linked to cell survival and proliferation, aberrant shedding of IECs may add to increased epithelial permeability. However, loss of LPA1 affects IEC proliferation without a significant effect on IEC apoptosis in vivo and in vitro.25 Therefore, aberrant epithelial cell death is unlikely a cause of barrier dysfunction.

Apical junctions, including TJ and AJ, are the primary determinant of paracellular permeability of epithelial cells.2 Although the current study was not intended for rigorous characterization of apical junction integrity by LPA1, it revealed that the loss of LPA1 led to decreased claudin-4, claudin-7, and E-cadherin expression in both mouse intestine and Caco-2 cells. However, a comparison of junctional protein expression between Lpa1−/− mice and Caco-2/cells with LPA1 knockdown revealed that LPA1 deletion decreased occludin expression in Caco-2 cells but not in mouse intestine. The reason for this discrepancy is not known. However, we postulate that the difference in occludin expression between Lpa1−/− and WT colons was likely underestimated because the lysate used for Western blotting was not composed entirely of epithelial cell lysates. Nevertheless, the epithelial dysfunction in Lpa1−/− mice was further demonstrated by the electron microscopic analysis that revealed aberrant apical junction structure in Lpa1−/− intestine. Previous studies have demonstrated the effects of LPA on paracellular permeability.44, 45 The finding that decreased LPA1 expression increases intestinal epithelial permeability is consistent with recent reports that LPA induced E-cadherin accumulation at the tight junction in lung epithelial cells.44, 45 On the other hand, others have reported that LPA increases tight junction permeability in endothelial cells.46, 47 The issues of cell-type–dependent effects of LPA require further investigation.

In lung epithelial cells, LPA regulates E-cadherin expression via activation of protein kinase Cδ and protein kinase Cζ.44 LPA1 activates PLC-β1 and PLC-β2, which hydrolyze phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate to generate inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacyglycerol.25, 48 Diacyglycerol activates novel protein kinase Cs, which include protein kinase Cδ.49 Therefore, the involvement of PLC-β in the regulation of TJ proteins by LPA using claudin-7 as the representative junctional protein was assessed. Inhibition of PLC-β by U31722 blocked the induction of claudin-7 by LPA in Caco-2 cells. Moreover, knockdown of PLC-β2, but not that of PLC-β1, ablated LPA-dependent regulation of claudin-7. Our previous study revealed distinct differences between PLC-β1 and PLC-β2 in regulation of IECs, in which PLC-β1 and PLC-β2 regulate cell proliferation and migration, respectively.25 PLC-β2 regulates IEC migration and epithelial restitution through a mechanism dependent on Rac1 and focal adhesion kinase.25 Hence, the current finding of PLC-β2–dependent regulation of claudin-7 is consistent with the previous reported role of PLC-β2 on IECs. Whether PLC-β2 is required for the regulation of other claudins, including claudin-2, and E-cadherin needs additional study.

Under inflammatory conditions, cells are exposed to a variety of cytokines, including TNF-α and INF-γ. TNF-α and INF-γ redistribute tight junction proteins, such as JAM-A, ZO1, and claudin-4, from the cell-cell junction into the cytoplasm.50, 51, 52 INF-γ rearranges actin and induces endocytic retrieval of tight junction proteins.53, 54 INF-γ activates RhoA and increases the expression of Rho-associated kinase, which, in turn, phosphorylates and activates myosin light chain (MLC).53, 55 TNF-α is found to transcriptionally regulate MLC kinase.56 Moreover, TNF-α and INF-γ synergistically up-regulate MLC kinase and MLC phosphorylation.38 Members of the Rho family small GTPases, RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42, are key regulators of the actin dynamics and paracellular permeability.57, 58 However, the effect of each GTPase on tight junction protein expression varies, and it was suggested that perturbation in barrier function reflects imbalance in GTPase activity and expression.59 Interestingly, it was reported that activation of Rac1 and Cdc42 leads to barrier protection of the Caco-2 monolayer, whereas RhoA and Rho-associated kinase are associated with barrier breakdown of both Caco-2 and T84 cells.60, 61 LPA is a known activator of Rho GTPases, and LPA-induced activation of RhoA has been observed in endothelial, muscle, neuronal, and cancer cells.34, 62, 63 LPA1 in IECs inhibits RhoA, whereas it activates Rac1.25 The activation of Rac1 by LPA1 is in contrast to LPA2-mediated activation of RhoA, which enhances tumorigenesis and inflammation.64 Therefore, we speculate that LPA-LPA1 signaling protects the intestinal epithelium from TNF-α/INF-γ–mediated barrier dysfunction, in part, by inactivation of RhoA and Rho-associated kinase and a decrease of MLC phosphorylation.

The current study demonstrated that the loss of LPA1 disrupted innate immunity by increasing epithelial defense against bacterial infiltration. Increased serum LPS and increased bacterial loads in the intestinal mucosa and peripheral organs were observed in Lpa1−/− mice. However, interestingly, despite these changes, Lpa1−/− mice did not develop spontaneous inflammation. Protective immunity to enteric bacteria, both in humans and experimental animals, is orchestrated by action of T cells, macrophages, and cytokines, including TNF, INF-γ, and IL-12.65 There was increased number of T cells, cytokine expression, and IgA secretion in Lpa1−/− mice. Recent studies of mice lacking JAM-A or nonmuscle myosin IIA showed that both JAM-A and nonmuscle myosin IIA knockout mice have a defective intestinal epithelial barrier, which renders them susceptible to DSS-induced colitis. Yet, these mice do not develop spontaneous colitis, the phenotypes that are similar to Lpa1−/− mice.66, 67 Khounlotham et al66 reported that elevated IgA production by CD4+ T cells protects JAM-A knockout mice by limiting bacterial translocation and intestinal mucosal inflammation. Our findings on Lpa1−/− mice suggest a similar mechanism limits inflammatory responses in Lpa1−/− mice, thereby protecting the animals in the unchallenged state. A caveat is that Lpa1−/− mice lack LPA1 in all cells and tissues. All lymphocytes and myeloid cells respond to LPA, although LPA receptor expression profiles in immune cells are incompletely known. LPA1 is expressed in both immature and mature dendritic cells.68 T cells have the highest expression of LPA2, whereas LPA1 is only expressed in activated T cells.69 Autotaxin, the enzyme generating extracellular LPA, is involved in aggravation of colitis by facilitating lymphocyte migration to the intestine.14 On the other hand, LPA1 is not involved in transmigration of T cells across the basal lamina of the high endothelial venules.70 A study of IEC-specific LPA1 deletion or elucidation of T-cell activation by LPA1 in vivo is not feasible because a conditional LPA1 deletion mouse strain is not available.

There is a correlation between epithelial dysfunction and increased inflammation caused by DSS.71, 72 On the contrary, increased immune tolerance and adaptation protect animals from inflammatory insults.27, 41 DSS induced more severe colonic damage and inflammation in Lpa1−/− mice. Moreover, a decreased number of proliferating IECs was observed in Lpa1−/− mice after DSS treatment, suggesting that the recovery from DSS-induced injury was delayed in Lpa1−/− mice. Consistently, pharmacologic inhibition of LPA1 during the recovery phase from DSS-induced injury impairs the recovery process.25 The increased mortality rate in Lpa1−/− mice compared with WT mice after DSS treatment further highlights the prolonged recovery process and increased inflammation in these mice, affecting the overall viability of the mice. LPA protects mice from TNF-induced diarrhea via LPA5.15 Together, we suggest that LPA contributes to the maintenance of the intestinal mucosal health by the restoration of barrier function and stimulation of transcellular fluid absorption via LPA1 and LPA5, respectively.

Currently, there is no evidence directly linking LPA to inflammatory bowel disease. However, a recent genome-wide association study linked a single-nucleotide polymorphism within G-protein–coupled receptor GPR35 (rs4676410) to inflammatory bowel disease.73 More important, LPA is reported to be an endogenous ligand of GPR35, associating aberrant LPA-mediated signaling to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease.74 GRP35 is reported to regulate neural excitation, and activation of GPR35 reduces inflammatory pain.75 Myenteric plexus primary cultures express LPA1, and LPA stimulates calcium transient in enteric glia.76 In addition, LPA1 is associated with cortical oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination.77 However, whether LPA1 regulates enteric neuron myelination and inflammatory pain in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease is unknown. Extracellular LPA is produced by autotaxin, which converts lysophosphatidylcholine to LPA.78 Interestingly, it has been shown that phosphatidylcholine is a component of colonic mucus and that ulcerative colitis patients have decreased levels of phosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylcholine.79 Given that phosphatidylcholine is a precursor of LPA,78 it is tempting to postulate that the low phosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylcholine levels in ulcerative colitis patients may also be associated with insufficient activation of LPA1.

In summary, this study identifies LPA1 as a regulator of intestinal epithelial barrier function. Despite the association of LPA with chronic diseases,10, 11 the current study further enforces the beneficial role of LPA in the intestinal tract, suggesting that specific targeting of individual LPA receptors should be considered for successful therapeutic treatment of chronic diseases via targeting of LPA signaling pathways.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Sam Molina for assisting with transepithelial electrical resistance measurements on Ussing chambers.

Footnotes

Supported by the VA Merit Award I01BX002540 and NIH grant R01DK071597 (C.C.Y.). Confocal microscopic analyses were supported, in part, by the Integrated Cellular Imaging Shared Resources of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and NIH/National Cancer Institute award P30CA138292. Funding for the JEOL JEM-1400 electron microscope was provided by NIH grant S10RR25679.

Disclosures: None declared.

Current address of S.-J.L., Department of Pharmaceutical Engineering, Daegu Haany University, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea; of J.-M.K., Division of Gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.10.006.

Supplemental Data

Depletion of LPA1 does not alter the F-actin cytoskeleton. A: F-actin (green) was visualized in the colonic sections of WT and Lpa1−/− mice. B: F-actin fluorescence staining of Caco-2 cells transfected with lentiviral shRNA targeting scramble control (shCon) or LPA1 (shLPA1). Scale bars = 10 μm (A and B).

References

- 1.Peterson L.W., Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:141–153. doi: 10.1038/nri3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsukita S., Furuse M., Itoh M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:285–293. doi: 10.1038/35067088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner J.R. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:799–809. doi: 10.1038/nri2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khor B., Gardet A., Xavier R.J. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bischoff S.C., Barbara G., Buurman W., Ockhuizen T., Schulzke J.-D., Serino M., Tilg H., Watson A., Wells J.M. Intestinal permeability: a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:189. doi: 10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman K., Desai C., Iyer S.S., Thorn N.E., Kumar P., Liu Y., Smith T., Neish A.S., Li H., Tan S., Wu P., Liu X., Yu Y., Farris A.B., Nusrat A., Parkos C.A., Anania F.A. Loss of junctional adhesion molecule A promotes severe steatohepatitis in mice on a diet high in saturated fat, fructose, and cholesterol. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:733–746.e712. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Floege J., Feehally J. The mucosa-kidney axis in IgA nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:147–156. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nouri M., Bredberg A., Westrom B., Lavasani S. Intestinal barrier dysfunction develops at the onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, and can be induced by adoptive transfer of auto-reactive T cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watts T., Berti I., Sapone A., Gerarduzzi T., Not T., Zielke R., Fasano A. Role of the intestinal tight junction modulator zonulin in the pathogenesis of type I diabetes in BB diabetic-prone rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2916–2921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500178102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi J.W., Herr D.R., Noguchi K., Yung Y.C., Lee C.W., Mutoh T., Lin M.E., Teo S.T., Park K.E., Mosley A.N., Chun J. LPA receptors: subtypes and biological actions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:157–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Houben A.J., Moolenaar W.H. Autotaxin and LPA receptor signaling in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30:557–565. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin S., Lee S.J., Shim H., Chun J., Yun C.C. The absence of LPA receptor 2 reduces the tumorigenesis by ApcMin mutation in the intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G1128–G1138. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00321.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin S., Wang D., Iyer S., Ghaleb A.M., Shim H., Yang V.W., Chun J., Yun C.C. The absence of LPA2 attenuates tumor formation in an experimental model of colitis-associated cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1711–1720. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hozumi H., Hokari R., Kurihara C., Narimatsu K., Sato H., Sato S., Ueda T., Higashiyama M., Okada Y., Watanabe C., Komoto S., Tomita K., Kawaguchi A., Nagao S., Miura S. Involvement of autotaxin/lysophospholipase D expression in intestinal vessels in aggravation of intestinal damage through lymphocyte migration. Lab Invest. 2013;93:508–519. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin S., Yeruva S., He P., Singh A.K., Zhang H., Chen M., Lamprecht G., de Jonge H.R., Tse M., Donowitz M., Hogema B.M., Chun J., Seidler U., Yun C.C. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates the intestinal brush border Na+/H+ exchanger 3 and fluid absorption via LPA5 and NHERF2. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:649–658. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.No Y.R., He P., Yoo B.K., Yun C.C. Regulation of NHE3 by lysophosphatidic acid is mediated by phosphorylation of NHE3 by RSK2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2015;309:C14–C21. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00067.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C., Dandridge K.S., Di A., Marrs K.L., Harris E.L., Roy K., Jackson J.S., Makarova N.V., Fujiwara Y., Farrar P.L., Nelson D.J., Tigyi G.J., Naren A.P. Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits cholera toxin-induced secretory diarrhea through CFTR-dependent protein interactions. J Exp Med. 2005;202:975–986. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q., Magnusson M.K., Mosher D.F. Lysophosphatidic acid and microtubule-destabilizing agents stimulate fibronectin matrix assembly through Rho-dependent actin stress fiber formation and cell contraction. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1415–1425. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sturm A., Sudermann T., Schulte K.M., Goebell H., Dignass A.U. Modulation of intestinal epithelial wound healing in vitro and in vivo by lysophosphatidic acid. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:368–377. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka T., Horiuchi G., Matsuoka M., Hirano K., Tokumura A., Koike T., Satouchi K. Formation of lysophosphatidic acid, a wound-healing lipid, during digestion of cabbage leaves. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2009;73:1293–1300. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adachi M., Horiuchi G., Ikematsu N., Tanaka T., Terao J., Satouchi K., Tokumura A. Intragastrically administered lysophosphatidic acids protect against gastric ulcer in rats under water-immersion restraint stress. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2252–2261. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Contos J.J.A., Fukushima N., Weiner J.A., Kaushal D., Chun J. Requirement for the lpA1 lysophosphatidic acid receptor gene in normal suckling behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13384–13389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gennero I., Laurencin-Dalicieux S., Conte-Auriol F., Briand-Mesange F., Laurencin D., Rue J., Beton N., Malet N., Mus M., Tokumura A., Bourin P., Vico L., Brunel G., Oreffo R.O., Chun J., Salles J.P. Absence of the lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA1 results in abnormal bone development and decreased bone mass. Bone. 2011;49:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon M.F., Daviaud D., Pradere J.P., Gres S., Guigne C., Wabitsch M., Chun J., Valet P., Saulnier-Blache J.S. Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits adipocyte differentiation via lysophosphatidic acid 1 receptor-dependent down-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14656–14662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412585200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S.J., Leoni G., Neumann P.A., Chun J., Nusrat A., Yun C.C. Distinct phospholipase C-beta isozymes mediate lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 effects on intestinal epithelial homeostasis and wound closure. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2016–2028. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00038-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Research Council . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laukoetter M.G., Nava P., Lee W.Y., Severson E.A., Capaldo C.T., Babbin B.A., Williams I.R., Koval M., Peatman E., Campbell J.A., Dermody T.S., Nusrat A., Parkos C.A. JAM-A regulates permeability and inflammation in the intestine in vivo. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3067–3076. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larmonier C.B., Laubitz D., Hill F.M., Shehab K.W., Lipinski L., Midura-Kiela M.T., McFadden R.M., Ramalingam R., Hassan K.A., Golebiewski M., Besselsen D.G., Ghishan F.K., Kiela P.R. Reduced colonic microbial diversity is associated with colitis in NHE3-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G667–G677. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00189.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper H.S., Murthy S.N., Shah R.S., Sedergran D.J. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Lab Invest. 1993;69:238–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieglstein C.F., Cerwinka W.H., Sprague A.G., Laroux F.S., Grisham M.B., Koteliansky V.E., Senninger N., Granger D.N., de Fougerolles A.R. Collagen-binding integrin alpha1beta1 regulates intestinal inflammation in experimental colitis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1773–1782. doi: 10.1172/JCI200215256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He P., Zhao L., Zhu L., Weinman E.J., De Giorgio R., Koval M., Srinivasan S., Yun C.C. Restoration of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3-containing macrocomplexes ameliorates diabetes-associated fluid loss. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3519–3531. doi: 10.1172/JCI79552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunzel D., Yu A.S. Claudins and the modulation of tight junction permeability. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:525–569. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D., Naydenov N.G., Feygin A., Baranwal S., Kuemmerle J.F., Ivanov A.I. Actin-depolymerizing factor and cofilin-1 have unique and overlapping functions in regulating intestinal epithelial junctions and mucosal inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:844–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parizi M., Howard E.W., Tomasek J.J. Regulation of LPA-promoted myofibroblast contraction: role of Rho, myosin light chain kinase, and myosin light chain phosphatase. Exp Cell Res. 2000;254:210–220. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macpherson A.J., McCoy K.D., Johansen F.E., Brandtzaeg P. The immune geography of IgA induction and function. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:11–22. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gkouskou K.K., Deligianni C., Tsatsanis C., Eliopoulos A.G. The gut microbiota in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:28. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Musch M.W., Clarke L.L., Mamah D., Gawenis L.R., Zhang Z., Ellsworth W., Shalowitz D., Mittal N., Efthimiou P., Alnadjim Z., Hurst S.D., Chang E.B., Barrett T.A. T cell activation causes diarrhea by increasing intestinal permeability and inhibiting epithelial Na+/K+-ATPase. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1739–1747. doi: 10.1172/JCI15695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang F., Graham W.V., Wang Y., Witkowski E.D., Schwarz B.T., Turner J.R. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergize to induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by up-regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:409–419. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62264-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Sadi R., Guo S., Ye D., Ma T.Y. TNF-alpha modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier is regulated by ERK1/2 activation of Elk-1. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1871–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amasheh S., Meiri N., Gitter A.H., Schoneberg T., Mankertz J., Schulzke J.D., Fromm M. Claudin-2 expression induces cation-selective channels in tight junctions of epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4969–4976. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmad R., Chaturvedi R., Olivares-Villagomez D., Habib T., Asim M., Shivesh P., Polk D.B., Wilson K.T., Washington M.K., Van Kaer L., Dhawan P., Singh A.B. Targeted colonic claudin-2 expression renders resistance to epithelial injury, induces immune suppression, and protects from colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:1340–1353. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farkas A.E., Hilgarth R.S., Capaldo C.T., Gerner-Smidt C., Powell D.R., Vertino P.M., Koval M., Parkos C.A., Nusrat A. HNF4alpha regulates claudin-7 protein expression during intestinal epithelial differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:2206–2218. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker D.L., Desiderio D.M., Miller D.D., Tolley B., Tigyi G.J. Direct quantitative analysis of lysophosphatidic acid molecular species by stable isotope dilution electrospray ionization liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2001;292:287–295. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He D., Su Y., Usatyuk P.V., Spannhake E.W., Kogut P., Solway J., Natarajan V., Zhao Y. Lysophosphatidic acid enhances pulmonary epithelial barrier integrity and protects endotoxin-induced epithelial barrier disruption and lung injury. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24123–24132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.007393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y., He D., Stern R., Usatyuk P.V., Spannhake E.W., Salgia R., Natarajan V. Lysophosphatidic acid modulates c-Met redistribution and hepatocyte growth factor/c-Met signaling in human bronchial epithelial cells through PKC delta and E-cadherin. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2329–2338. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schulze C., Smales C., Rubin L.L., Staddon J.M. Lysophosphatidic acid increases tight junction permeability in cultured brain endothelial cells. J Neurochem. 1997;68:991–1000. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68030991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirase T., Kawashima S., Wong E.Y., Ueyama T., Rikitake Y., Tsukita S., Yokoyama M., Staddon J.M. Regulation of tight junction permeability and occludin phosphorylation by Rhoa-p160ROCK-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10423–10431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suh P.G., Park J.I., Manzoli L., Cocco L., Peak J.C., Katan M., Fukami K., Kataoka T., Yun S., Ryu S.H. Multiple roles of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isozymes. BMB Reports. 2008;41:415–434. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.6.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koivunen J., Aaltonen V., Peltonen J. Protein kinase C (PKC) family in cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2006;235:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma T.Y., Iwamoto G.K., Hoa N.T., Akotia V., Pedram A., Boivin M.A., Said H.M. TNF-alpha-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability requires NF-kappa B activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G367–G376. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00173.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prasad S., Mingrino R., Kaukinen K., Hayes K.L., Powell R.M., MacDonald T.T., Collins J.E. Inflammatory processes have differential effects on claudins 2, 3 and 4 in colonic epithelial cells. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1139–1162. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monteiro A.C., Parkos C.A. Intracellular mediators of JAM-A–dependent epithelial barrier function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1257:115–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Utech M., Ivanov A.I., Samarin S.N., Bruewer M., Turner J.R., Mrsny R.J., Parkos C.A., Nusrat A. Mechanism of IFN-gamma-induced endocytosis of tight junction proteins: myosin II-dependent vacuolarization of the apical plasma membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5040–5052. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Youakim A., Ahdieh M. Interferon-γ decreases barrier function in T84 cells by reducing ZO-1 levels and disrupting apical actin. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1279–G1288. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.5.G1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shen L., Black E.D., Witkowski E.D., Lencer W.I., Guerriero V., Schneeberger E.E., Turner J.R. Myosin light chain phosphorylation regulates barrier function by remodeling tight junction structure. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2095–2106. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma T.Y., Boivin M.A., Ye D., Pedram A., Said H.M. Mechanism of TNF-{alpha} modulation of Caco-2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier: role of myosin light-chain kinase protein expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G422–G430. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00412.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nusrat A., Giry M., Turner J.R., Colgan S.P., Parkos C.A., Carnes D., Lemichez E., Boquet P., Madara J.L. Rho protein regulates tight junctions and perijunctional actin organization in polarized epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10629–10633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bruewer M., Hopkins A.M., Hobert M.E., Nusrat A., Madara J.L. RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 exert distinct effects on epithelial barrier via selective structural and biochemical modulation of junctional proteins and F-actin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C327–C335. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00087.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Samarin S.N., Ivanov A.I., Flatau G., Parkos C.A., Nusrat A. Rho/Rho-associated kinase-II signaling mediates disassembly of epithelial apical junctions. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3429–3439. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schlegel N., Meir M., Spindler V., Germer C.T., Waschke J. Differential role of Rho GTPases in intestinal epithelial barrier regulation in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1196–1203. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim J.H., Adelstein R.S. LPA1-induced migration requires nonmuscle myosin II light chain phosphorylation in breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2881–2893. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Amerongen G.P.V., Vermeer M.A., van Hinsbergh V.W.M. Role of RhoA and Rho kinase in lysophosphatidic acid-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:E127–E133. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.e127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang H., Wang D., Sun H., Hall R.A., Yun C.C. MAGI-3 regulates LPA-induced activation of Erk and RhoA. Cell Signal. 2007;19:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bergstrom K.S., Sham H.P., Zarepour M., Vallance B.A. Innate host responses to enteric bacterial pathogens: a balancing act between resistance and tolerance. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:475–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khounlotham M., Kim W., Peatman E., Nava P., Medina-Contreras O., Addis C., Koch S., Fournier B., Nusrat A., Denning Timothy L., Parkos Charles A. Compromised intestinal epithelial barrier induces adaptive immune compensation that protects from colitis. Immunity. 2012;37:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Naydenov N.G., Feygin A., Wang D., Kuemmerle J.F., Harris G., Conti M.A., Adelstein R.S., Ivanov A.I. Nonmuscle myosin IIA regulates intestinal epithelial barrier in vivo and plays a protective role during experimental colitis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24161. doi: 10.1038/srep24161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Panther E., Idzko M., Corinti S., Ferrari D., Herouy Y., Mockenhaupt M., Dichmann S., Gebicke-Haerter P., Di Virgilio F., Girolomoni G., Norgauer J. The influence of lysophosphatidic acid on the functions of human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:4129–4135. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goetzl E.J., Kong Y., Voice J.K. Cutting edge: differential constitutive expression of functional receptors for lysophosphatidic acid by human blood lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164:4996–4999. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.4996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bai Z., Cai L., Umemoto E., Takeda A., Tohya K., Komai Y., Veeraveedu P.T., Hata E., Sugiura Y., Kubo A., Suematsu M., Hayasaka H., Okudaira S., Aoki J., Tanaka T., Albers H.M., Ovaa H., Miyasaka M. Constitutive lymphocyte transmigration across the basal lamina of high endothelial venules is regulated by the autotaxin/lysophosphatidic acid axis. J Immunol. 2013;190:2036–2048. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Poritz L.S., Garver K.I., Green C., Fitzpatrick L., Ruggiero F., Koltun W.A. Loss of the tight junction protein ZO-1 in dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis. J Surg Res. 2007;140:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Citalan-Madrid A.F., Vargas-Robles H., Garcia-Ponce A., Shibayama M., Betanzos A., Nava P., Salinas-Lara C., Rottner K., Mennigen R., Schnoor M. Cortactin deficiency causes increased RhoA/ROCK1-dependent actomyosin contractility, intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction, and disproportionately severe DSS-induced colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:1237–1247. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Imielinski M., Baldassano R.N., Griffiths A., Russell R.K., Annese V., Dubinsky M. Common variants at five new loci associated with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1335–1340. doi: 10.1038/ng.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.MacKenzie A., Lappin J., Taylor D., Nicklin S., Milligan G. GPR35 as a novel therapeutic target. Front Endocrinol. 2011;2:68. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cosi C., Mannaioni G., Cozzi A., Carlà V., Sili M., Cavone L., Maratea D., Moroni F. G-protein coupled receptor 35 (GPR35) activation and inflammatory pain: studies on the antinociceptive effects of kynurenic acid and zaprinast. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:1227–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Segura B.J., Zhang W., Cowles R.A., Xiao L., Lin T.R., Logsdon C., Mulholland M.W. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates calcium transients in enteric glia. Neuroscience. 2004;123:687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Garcia-Diaz B., Riquelme R., Varela-Nieto I., Jimenez A.J., de Diego I., Gomez-Conde A.I., Matas-Rico E., Aguirre J.A., Chun J., Pedraza C., Santin L.J., Fernandez O., Rodriguez de Fonseca F., Estivill-Torrus G. Loss of lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA1 alters oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination in the mouse cerebral cortex. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:3701–3720. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.D'Arrigo P., Servi S. Synthesis of lysophospholipids. Molecules. 2010;15:1354–1377. doi: 10.3390/molecules15031354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ehehalt R., Braun A., Karner M., Fullekrug J., Stremmel W. Phosphatidylcholine as a constituent in the colonic mucosal barrier: physiological and clinical relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:983–993. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Depletion of LPA1 does not alter the F-actin cytoskeleton. A: F-actin (green) was visualized in the colonic sections of WT and Lpa1−/− mice. B: F-actin fluorescence staining of Caco-2 cells transfected with lentiviral shRNA targeting scramble control (shCon) or LPA1 (shLPA1). Scale bars = 10 μm (A and B).