Abstract

Among individuals living with HIV disease, approximately 60% experience problems with everyday functioning. The present study investigated the utility of the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment-Brief Version (UPSA-B) as a measure of functional capacity in HIV. We utilized a cross-sectional three-group design comparing individuals with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HIV+HAND+; n=27), HIV+ neurocognitively normal individuals (HIV+HAND−; n=51), and an HIV− comparison group (HIV−; n=28) with broadly comparable demographics and non-HIV comorbidities. Participants were administered the UPSA-B, the Medication Management Test-Revised (MMT-R), and were assessed for manifest everyday functioning and quality of life, as part of a standardized clinical neurocognitive research battery. Results indicated that the HIV+HAND+ group had significantly lower UPSA-B scores than the HIV+HAND− group, but did not differ from the HIV− group. Among HIV+ individuals, UPSA-B scores were significantly related to MMT-R scores, all neurocognitive domains assessed, and education, but the UPSA-B was not related to manifest everyday functioning (e.g., unemployment), health-related quality of life, or HIV disease variables. Findings provide mixed support for the construct validity of the UPSA-B in HIV. Individuals impaired on the UPSA-B may be at increased risk for HAND, but the extent to which it detects general manifest everyday functioning problems is uncertain.

Keywords: HIV, everyday functioning, neurocognitive disorders, functional capacity

It is estimated that nearly 60% of individuals living with HIV disease evidence problems with everyday functioning (Blackstone et al., 2013). Common everyday functioning difficulties in HIV include poorer employment outcomes (Dray-Spira et al., 2006), financial management (Heaton et al., 2004), driving abilities (Marcotte et al., 2004), and health behaviors (e.g., medication adherence; Hinkin et al., 2004). Robust predictors of everyday functioning deficits in HIV disease include lower cognitive reserve, neurocognitive impairment, advanced disease (e.g., immunosuppression), and neuropsychiatric complications (e.g., depression, substance abuse) (e.g., Blackstone et al., 2012; Gorman, Foley, Ettenhofer, Hinkin, & van Gorp, 2009; Heaton et al., 2004; Morgan et al., 2012). Critically, these everyday functioning impairments are associated with adverse downstream outcomes such as lower quality of life (Kamat, Woods, Cameron, Iudicello, & the HNRP Group, 2016; Moore et al., 2014; Woods et al., 2015) and increased rates of mortality (Shen, Blank, & Selwyn, 2005). Thus, it is critical to be able to reliably assess for problems of everyday living skills in individuals infected with HIV (Blackstone et al., 2012).

Detection of everyday functioning problems can vary depending on whether one utilizes measures of manifest everyday functioning (e.g., what one actually does in daily life) or measures of functional capacity (e.g., what one can do under ideal circumstances; Mantovani et al., 2015). Ideally, a clinical evaluation of everyday functioning would draw data from multiple sources including patient report, proxy-report, caregiver rating scales, and observations of behaviors in the real world, and should focus on both manifest functioning and functional capacity. Manifest everyday functioning refers to the level and independence at which one performs activities of daily living in their real lives (e.g., whether they are employed or can properly adhere to their prescribed medication regimen), which are the clinical gold standard but can oftentimes be very difficult to operationalize and measure reliably. Self-report methods of measuring manifest everyday functioning can be affected by limited insight (Chesney et al., 2000; Thames, Kim, et al., 2011) and mood (Heaton et al., 2004; Thames, Becker, et al., 2011). Unfortunately, however, there are few objective, reliable measures of manifest functioning in current use. By way of contrast, functional capacity is defined as the ability to perform daily tasks (e.g., balancing a checkbook) in a controlled laboratory setting in which outside distractions (e.g., other ongoing activities) and compensatory strategies (e.g., writing down lists) are minimized. A major limitation of performance-based functional capacity measures of everyday functioning is that they sometimes do not reflect how individuals perform in the real world (i.e., manifest everyday functioning), which may be attributable to the simplicity of the tasks, restrictions on compensatory strategy use, motivation, and real-world demands. Yet performance-based measures have several notable strengths, including being standardized, relatively unaffected by mood and insight (Gould et al., 2015; Leifker, Bowie, & Harvey, 2009), and they can be closely related in content to real-world tasks, which lend themselves well to use in clinic and research.

There are numerous performance-based assessment used to measure functional capacity that have been studied and utilized in HIV disease, including driving simulators (Vance, Fazeli, Ball, Slater, & Ross, 2014), standardized work samples (e.g., MESA SF2; Blackstone et al., 2012), and the Medication Management Test-Revised (MMT-R; e.g., Patton et al., 2012). The MMT-R consists of individuals accurately dispensing medications according to a fictitious prescription regimen, for which the real world correlate is particularly important for health outcomes in HIV. The MMT-R has been shown to have a modest relationship with real-world adherence in advanced HIV disease (Patton et al., 2012), and its use is indicated in increased sensitivity at identifying syndromic HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND; Blackstone et al., 2012). The strengths of the MMT-R are that it is a standardized, objective, capacity-based measure with established psychometrics and closely parallels in the laboratory the task of managing medications in the real-world (Patton et al., 2012). However, the MMT-R can be time intensive, lacks normative standards, and while it has shown significant relationships with adherence in the real world, these relationships tend to have small effect sizes (Patton et al., 2012). Moreover, the MMT-R only assesses a single functional domain. As such, there remains a need for a multi-domain assessment of everyday functioning in HIV disease.

The UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment-Brief Version (UPSA-B) is a performance-based assessment used to measure functional capacity that may reliably detect everyday functioning problems. The UPSA was originally developed and validated in samples of individuals with serious mental illness (Patterson, Goldman, McKibbin, Hughs, & Jeste, 2001), and the abbreviated version of the UPSA (UPSA-B) also was validated in schizophrenia (Mausbach, Harvey, Goldman, Jeste, & Patterson, 2007). The UPSA-B is administered over approximately 10–15 minutes and assesses both financial and communication skills through 4 tasks: counting money and making change, paying bills, telephone use, and a medical appointment rescheduling task. The UPSA-B has shown sensitivity in detecting serious mental illness and is associated with employment status, residential independence, daily living skills, and work skills (Mausbach et al., 2007; Mausbach, et al., 2008; Mausbach et al., 2011). It also has evidence good psychometrics including acceptable domain homogeneity, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity with other established capacity-based measures of everyday functioning (Olsson, Helldin, Hjärthag, & Norlander, 2012). Examining the construct validity of the UPSA-B in HIV disease is a logical and important next step for both establishing broader construct validity of the UPSA-B and in identifying novel ways to characterize functional capacity in HIV disease, which may then in turn aid the broader objective of characterizing HAND.

The aim of the current study is to investigate the utility of using the UPSA-B as a performance-based assessment used to measure functional capacity in a sample of individuals living with HIV disease, and to establish characterization accuracy using UPSA-B scores in predicting HAND versus normal cognition within HIV. We examined the associations of the UPSA-B with measures of functional capacity previously validated in HIV (i.e., Medication Management Test; Patton et al., 2012), as well as with manifest functioning variables (i.e., activities of daily living, employment status, Karnofsky performance rating, cognitive symptoms) and neuropsychological performance.

Method

Participants

This study was approved by UC San Diego’s human research protections program. Participants included 78 HIV+ participants and 28 HIV− participants with broadly comparable demographics (see Table 1). HIV+ participants and HIV− participants were recruited concurrently from the general San Diego area (e.g., community newspaper advertisements and HIV treatment centers). Inclusion criteria consisted of confirmation of HIV serostatus and the ability to provide informed consent on the day of evaluation. Exclusion criteria included presence of a psychotic disorder (e.g., schizophrenia), neurological complications known to adversely affect cognition (e.g., seizure disorder, active opportunistic infection), or a verbal IQ estimate of <70 (based on the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading, WTAR; Psychological Corporation, 2001). Additionally, participants were excluded if they met DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) for substance dependence (including alcohol) within 1 month of evaluation (as determined by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, CIDI version 2.1; World Health Organization, 1998), had a urine toxicology screen positive for illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine and methamphetamine) on the day of evaluation (excluding marijuana), or a Breathalyzer test that was positive for alcohol. There were no differences in inclusion or exclusion criteria between HIV+ participants and our HIV− group.

Table 1.

Median (Q1, Q3) demographic, cognitive, mood, substance use, medical, disease, and everyday functioning characteristics for the HIV+HAND+, HIV+HAND−, and HIV− groups

| Variable | HIV+HAND+ (n=27) | HIV+HAND− (n=51) | HIV− (n=28) | p | Group Differencesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 49 (45, 54) | 48 (40, 53) | 51 (36.3, 56) | .541 | |

| Education (years) | 13 (12, 16) | 13 (12, 16) | 13 (12, 16) | .781 | |

| Gender n (%) (male) | 24 (88.9) | 46 (90.2) | 17 (60.7) | .005 | HIV− < HIV+HAND−, HIV+HAND+ |

| Ethnicity | .543 | ||||

| Caucasian n (%) | 17 (63.0) | 29 (56.9) | 17 (60.7) | ||

| African American n (%) | 3 (11.1) | 12 (23.5) | 5 (17.9) | ||

| Hispanic n (%) | 6 (22.2) | 6 (11.8) | 5 (17.9) | ||

| Asian n (%) | 1 (3.7) | 3 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Native American n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (3.5) | ||

| Cognitive, Mood, and Substance Use | |||||

| Neuropsychological Impairment n (%) | 27 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (25.0) | <.001 | HIV+HAND− < HIV− < HIV+HAND+ |

| POMS total mood disturbance (of 200) | 50 (22, 90) | 40.5 (21.8, 60.5) | 28 (20.5, 52.5) | .121 | |

| Major Depressive Disorderb n (%) | 19 (70.4) | 29 (56.0) | 6 (21.4) | <.001 | HIV− < HIV+HAND−, HIV+HAND+ |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorderb n (%) | 6 (22.2) | 3 (6.3) | 3 (10.7) | .134 | |

| Substance Use Dependenceb n (%) | 17 (63.0) | 25 (49.0) | 7 (25.0) | .014 | HIV− < HIV+HAND−, HIV+HAND+ |

| Medical | |||||

| Hepatitis C virus infection n (%) | 4 (14.8) | 5 (10.2) | 5 (17.9) | .622 | |

| AIDS n (%) | 18 (66.7) | 28 (55.1) | -- | .323 | |

| Estimated Duration of Infection (years) | 12.5 (7.4, 19.0) | 9.4 (4.5, 22.3) | -- | .470 | |

| Current CD4 (cells/μL) | 661 (335, 853) | 659 (393.5, 853.5) | -- | .770 | |

| Nadir CD4 (cells/μL) | 148 (13, 300) | 201 (73, 336.5) | -- | .250 | |

| RNA Plasma (cells/μL) | 1.6 (1.6, 1.6) | 1.6 (1.6, 1.6) | -- | .100 | |

| RNA CSF (cells/μL) | 1.6 (1.6, 1.6) | 1.6 (1.6, 1.6) | -- | .462 | |

| CPE | 7 (6, 7) | 7 (7, 8) | -- | .076 | |

| Everyday Functioning | |||||

| Manifest Functioning Composite (of 5) | 2 (1, 3) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 1) | .004 | HIV− < HIV+HAND+ |

| Instrumental ADLs (# of declines) | 1 (0, 1.5) | 0 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 0) | .005 | HIV− < HIV+HAND−, HIV+HAND+ |

| Basic ADLs (# of declines) | 0 (0, 1.3) | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 0) | .059 | |

| Unemployment n (%) | 17 (63.0) | 24 (47.1) | 13 (46.4) | .347 | |

| Karnofsky (of 100) | 90 (80, 100) | 100 (90, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | <.001 | HIV−, HIV+HAND− < HIV+HAND+ |

| PAOFI (of 33) | 3 (1, 9) | 1 (0, 5) | 1 (0, 2) | .023 | HIV− < HIV+HAND+ |

Note. POMS = Profile of Mood States; CD4 = cluster of differentiation; CPE = CNS Penetration-Effectiveness Rank; ADLs = activities of daily living; PAOFI = Patient’s Assessment of Own Functioning

Determined using Tukey HSD post hoc tests for normally distributed data, or Steel-Dwass All Pairs post hoc tests for non-normally distributed data

Any lifetime diagnosis of dependence on alcohol or illicit substances.

Materials and Procedure

After providing written, informed consent, all participants completed psychiatric, neuropsychological, and standardized medical research evaluations, for which they received nominal financial compensation.

Everyday functioning outcomes

UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment-Brief Version (UPSA-B)

Participants completed the brief version of the UPSA-B (Mausbach et al., 2007) as a performance-based assessment used to measure functional capacity. Functional domains on the UPSA-B include financial skills and communication skills, which are assessed independently. In the financial skills module, participants were asked to count change, generate change from an item purchased at a store, and pay a utility bill with a check. In the communication skills module, participants were asked to complete tasks including dialing a telephone to contact emergency services, calling information in order to obtain a telephone number, and calling a doctor in order to reschedule an appointment. For each domain we calculated a score using the total percent correct and then converting this score to a standardized score ranging from 0–50, with higher scores indicating better performance. We then calculated a summary score by summing both domain scores (range =0–100), with higher scores indicating better functional capacity.

Medication management test, revised (MMT-R)

The MMT-R is a measure of one’s ability to accurately dispense medications according to a fictitious prescription regimen and answer questions about mock medications. The MMT-R takes about 10 minutes to complete and includes elements from a “pill dispensing” component and a “medication inference” component. In the former component, participants are observed and scored with respect to their ability to dispense one day’s dosage and follow a fictitious prescription regimen, which includes 5 different mock medications consistent with many of the current therapies that are used in the treatment of HIV. Pill bottles are provided with realistic instructions on standardized labels. As part of this task, participants must transfer the correct number of pills from the pill bottles to a medication organizer designed to hold a 1-week’s supply of medication. Participants are scored on the total percentage of prescriptions that they correctly place in the organizer. The “medication inference” component includes 7 items presented in ascending order of difficulty, and requires participants to answer questions regarding the mock medications as well as one over-the-counter medication insert. Total scores on the MMT-R range from 0 to 10. Consistent with prior research, impairment on the MMT-R was defined as scores of five or below (Heaton et al., 2004).

Manifest everyday functioning

Participants were administered a series of manifest everyday functioning measures that were used to index a composite manifest everyday functioning score ranging from 0 (no domains “dependent”) to 5 (5 domains “dependent”), with higher scores indicating higher levels of functional dependence. Domains included: (1) instrumental activities of daily living (iADLs; e.g., finance management), (2) basic ADLs (bADLs; e.g., dressing), (3) employment status, (4) a physician’s rating of functioning, and (5) the patient’s own assessment of overall functioning. For iADLs and bADLs, participants were administered a modified version of the Lawton and Brody (1969) ADL scale described in Heaton et al. (2004), and individuals were considered “dependent” within either domain if they reported 2 or more ADL declines. Participants were determined as employed or unemployed (not due to elective retirement) through self-report. All participants were administered the Karnofsky Scale of Performance (Karnofsky & Burchenal, 1949), which is a physician’s rating of overall functioning (range 0 [dead] to 100 [normal, no evidence of disease]) previously applied in HIV samples (Gandhi et al., 2011; Morgan et al., 2012), and “dependence” for this domain operationalized as having a score < 90. Participants were assessed using the Patient’s Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory (PAOFI), which is a measure of participants’ perceptions of the extent to which symptoms affect their functioning on occupational, social, and family-related tasks (Chelune & Lehman, 1986), and “dependence” operationalized as endorsing ≥ 3 domains as elevated.

Quality of life

Participants completed the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36; Ware, Snow, Kosinski, & Gandek, 1993) as an assessment of health-related quality of life. The SF-36 consists of 2 summary scores: physical health (physical functioning, physical role limitations, bodily pain, general health) and mental health (emotional role limitations, energy/fatigue, social functioning, emotional well-being). Domains are then summed to create two domains (range 0–100)—a physical health summary score and a mental health summary score, each ranging 0–100 and higher scores corresponding to better health status. We elected to include the SF-36 since previous studies in HIV have shown that quality of life is related to neurocognitive impairment (Tozzi et al., 2003; Osowiecki et al., 2000) as well as self-reported problems with everyday functioning (Doyle et al., 2012). Furthermore, previous investigations into performance-based measures of functional capacity outside of HIV have shown associations with quality of life (e.g., schizophrenia; Patterson et al., 2002). Thus, we aimed to determine whether the UPSA-B, being a performance-based capacity measure of everyday functioning, might also be related quality of life in HIV and thus give additional insight into the validity of UPSA-B in predicting important real-world outcomes in HIV.

Neurocognitive outcomes

HAND designations were derived from a standardized neuropsychological battery using established procedures (see Doyle, Morgan, Weber, Woods, & the HNRP Group, 2015) for purposes of establishing characterization accuracy using UPSA-B scores in predicting HAND versus normal cognition within HIV, and we measured neuropsychological impairment in the HIV− group using identical methodology used for our HIV+ groups (HIV+HAND−, HIV+HAND+). The domains included: (1) learning: Total Trials 1–3 from the Hopkin’s Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R; Brandt & Benedict, 1991) and Total Trials 1–3 of the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised (BVMT-R; Benedict & Groninger, 1995); (2) memory: Delayed free recall trial from the HVLT-R and the delayed free recall trial from the BVMT-R; (3) attention and processing speed: time to complete Trailmaking Test, Part A (Army Individual Test Battery, 1944), digit span total score from the Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd edition (WAIS-III; Psychological Corporation, 1997), and total correct on the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT; Gronwall, 1977); (4) executive functions: time to complete Trailmaking Test, Part B (Army Individual Test Battery, 1944) and total perseverative responses from the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; Kongs, Thompson, Iverson, & Heaton, 2000); (5) fluency: total words from animal fluency and total words generated from letter fluency from the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT-FAS; Benton, Hamsher, & Sivan, 1983; Gladsjo et al., 1999); and (6) motor: Grooved Pegboard dominant and non-dominant total time (Kløve, 1963). We diagnosed HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HIV+HAND+), meaning that cognitive impairment was at least partially attributable to HIV disease, per Frascati criteria (Antinori et al., 2007). Individual normed T-scores for each test were converted into deficit scores (range = 0 [normal] to 5 [severe]; see Carey et al. 2004 for details) and averaged to generate neurocognitive domain scores and a Global Deficit Score (GDS; Carey et al. 2004) that were used to determine HAND per Frascati criteria.

We diagnosed individuals within the HIV+HAND+ group as having asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (HIV+HAND+ANI), minor neurocognitive disorder (HIV+HAND+MND), or HIV-associated dementia (HIV+HAND+HAD) using cognitive and everyday functioning variables to determine subsyndromic or syndromic severity consistent with Frascati criteria (Antinori et al., 2007). Within the entire HIV+ group, 12.8% (n=10) of individuals were designated as HIV+HAND+ANI, 21.8% (n=17) of individuals were designated as HIV+HAND+MND, while no individuals were designated as having HIV+HAND+HAD. 65.4% (n=51) of individuals were HIV+HAND−. Our small sample size of HIV+HAND+ individuals precluded us from making robust inferences into UPSA-B performances across syndromic (i.e., everyday functioning problems) versus subsyndromic (i.e., no problems with everyday functioning) neurocognitive disorders in HIV. Indeed, previous studies in HIV also have made similar exploratory examinations despite small base rates of syndromic HAND (e.g., Sheppard et al., 2015). However, given the importance of determining everyday functioning status for HAND, it is important to examine whether UPSA-B performance parallels the well-studied neurocognitive disorder severities most commonly used in neuroAIDS literature. As such, UPSA-B performances differences across severity types within the HIV+HAND+ group were determined in order to determine the possible added clinical utility of the UPSA-B in determining common neuroAIDS nosology for HAND, despite the limitations with small sample sizes.

In order to examine the potential underlying neuropsychological functions supporting UPSA-B performance, we included the domains and associated measures detailed above (for HIV+HAND+ designations) and constructed raw score composites (i.e., z-scores derived from mean raw scores within the HIV+ group only). We elected to utilize sample-based z-scores in order to establish a common metric when creating domain composites and to create a normal distribution for each variable.

Statistical Analyses

Total UPSA-B scores in the sample were non-normally distributed (Shapiro Wilk W = 0.93, p < .001); therefore, non-parametric analyses were used. Although the three study groups differed in gender and the frequency of Major Depressive Disorder and substance use dependence (see Table 1), neither of these variables were associated with the UPSA-B (both ps > .10) and thus do not represent confounding factors. To investigate the diagnostic validity of the UPSA-B, Kruskal-Wallis test was used to examine the three-level (HIV−, HIV+HAND−, HIV+HAND+) HAND variable as the independent variable predicting UPSA-B total as the dependent variable. Steel-Dwass All Pairs post hoc tests were used to examine pair-wise comparisons between the three groups. A separate Kruskal-Wallis test within the entire HIV+ group using HAND syndromic classification groups (HIV+HAND−, HIV+HAND+ANI, HIV+HAND+MND) as the predictor and UPSA-B performance as the dependent variable was used to examine possible differences across the three groups, and planned post hoc tests were planned to examine possible group differences using Steel-Dwass All Pairs tests. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to assess classification accuracy using UPSA-B scores in predicting HIV+HAND- versus HIV+HAND+. Since this study was focused on determining the construct validity of the UPSA-B and aimed to determine the potential clinical utility of the UPSA-B in determining HAND status among persons with HIV disease, it is important to examine the classification accuracy of the UPSA-B for HAND status, given that simple mean differences (even when accompanied by effect sizes) are not optimally useful to clinicians.

To explore the convergent validity of the UPSA-B, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to examine the possible association between UPSA-B and another performance-based assessment used to measure functional capacity, the MMT-R, within a subgroup of HIV+ individuals from this study that had MMT-R data (N = 42). We also examined the possible independent association between UPSA-B and manifest everyday functioning composite of impaired domains (i.e., unemployment, iADL dependence, bADL dependence, physician’s rating of functioning, patient’s own assessment of overall functioning) in the entire HIV+ group. Since previous research has found robust predictors of everyday functioning in HIV as including lower cognitive reserve, neurocognitive impairment, neuropsychiatric complications, and immunosuppression (Blackstone et al., 2012; Heaton et al., 2004; Morgan et al., 2012), UPSA-B total scores also were included in a single linear regression along with a priori derived covariates.

We used Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients or Kruskal-Wallis tests to examine possible associations between UPSA-B scores and demographic, cognitive, and medical associations in the HIV group. To account for multiple comparisons, we computed a false discovery rate α value for each comparison (see Table 2) utilizing the protocol described in Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). In addition, we conducted power analyses utilizing the median α (.026) for these comparisons, which determined that there was sufficient power for detecting medium (1- β = .87) and large (1- β > .95) effects using spearman rho correlation analyses (e.g., correlations with continuous variables) and for detecting large (1- β = .88) effects for Kruskal-Wallis test analyses (e.g., comparisons between levels of a categorical variable).

Table 2.

Demographic, cognitive, and HIV disease characteristic associations and correlations with UPSA-B within the HIV+ group.

| Variable | False Discovery Rate α | p | Effect Size (rs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | .0361 | .5206 | .07 |

| Education | .0028 | <.0001* | .45 |

| Gender (% Female)a,b | .0306 | .1909 | .23 |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian)a,b | .0278 | .1634 | .17 |

| Cognitive | |||

| Global Cognition | .0056 | <.0001* | .47 |

| Attention/Processing Speed | .0083 | <.0001* | .49 |

| Learning | .0194 | .0035* | .33 |

| Delayed Memory | .0139 | .0019* | .35 |

| Executive Functions | .0167 | .0030* | .33 |

| Verbal Fluency | .0111 | .0002* | .41 |

| Motor | .0222 | .0068* | .30 |

| Medical | |||

| Hepatitis C virus infectiona,b | .0472 | .8335 | .05 |

| AIDSa,b | .0500 | .9619 | .03 |

| Estimated Duration of Infection | .0444 | .5711 | .07 |

| Current CD4 | .0333 | .2050 | .15 |

| Nadir CD4 | .0416 | .5265 | .07 |

| RNA Plasma | .0250 | .0363 | −.24 |

| RNA CSF | .0361 | .3043 | −.16 |

Note. CD4 = cluster of differentiation.

Approximate effect size ρ computed from Cohen’s d value using formula rs =[d2/(d2+4)]1/2

p value derived from Kruskal-Wallis test.

p < False discovery rate α

Results

Diagnostic Validity of the UPSA-B: Group-level Differences

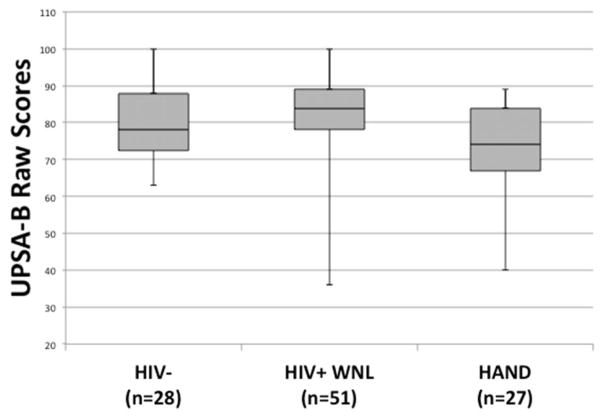

Results revealed a significant omnibus difference on UPSA-B performance across the three groups (χ2[2] = 8.93, p = .012; see Figure 1). Steel-Dwass All Pairs post hoc tests revealed that the HIV+HAND+ group had significantly lower UPSA-B scores than did the HIV+HAND− group (Z = −2.97, p = .008, Cliff’s d = −.41). There was no difference between the HIV− group and either the HIV+HAND+ (Z = −1.47, p = .306, Cliff’s d = −.23) or HIV+HAND− group (Z = 1.29, p = .400, Cliff’s d = .18). A separate Kruskall-Wallis test examining HIV+HAND− and HIV+HAND+ syndromic (ANI, MND) classification groups revealed a statistically significant difference across the three groups (χ2[2] = 9.52, p = .009). Steel-Dwass All Pairs post hoc tests revealed that the HIV+HAND+MND group had significantly lower UPSA-B scores than did the HIV+HAND− (Z = −2.93, p = .009, Cliff’s d = 0.48). There was no difference between the HIV+HAND+ANI group and either the HIV+HAND− (Z = −1.47, p = .305, Cliff’s d = 0.30) or HIV+HAND+MND group (Z = 0.83, p = .684, Cliff’s d = −0.20). UPSA-B scores did not differ between the HIV− and HIV+HAND+MND groups (Z = −1.74, p = .304, Cliff’s d = 0.31).

Figure 1.

Box-and-whisker plots for UPSA-B scores (possible range 0–100) among the HIV−, HIV+ neurocognitively normal (HIV+HAND−), and HIV+ neurocognitively impaired (HIV+HAND+) groups.

The area under the curve (AUC) value for UPSA-B predicting HAND was 0.70. Utilizing an UPSA-B cutoff score that that maximized both sensitivity (.74) and specificity (.59) as determined by Youden’s index (UPSA-B total score ≤ 83), there was an overall classification agreement of 64.10%, kappa of .29 (95% CI [.10, .49]), a positive predictive value (PPV) of .49, a negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.81, and an odds ratio of 4.08 (95% CI [1.46, 11.46]) in classifying HIV+HAND+ individuals within the entire HIV+ group.

Convergent validity of the UPSA-B in HIV

To examine convergent validity of the UPSA-B in HIV, a Spearman’s rho correlation revealed that UPSA-B scores were significantly and strongly related to MMT scores (rs = .48, p =.001). A Spearman’s rho correlation revealed that the association between UPSA-B scores and the manifest everyday functioning composite did not reach statistical significance (rs = −.03, p =.790). The overall model with UPSA-B scores along with a priori covariates (i.e., education, lifetime affective disorder, global neurocognitive impairment, AIDS status) predicting the manifest everyday functioning composite reached statistical significance, F(5,70) = 3.03, p = .016, R2 adjusted = .119. However, UPSA-B was not an independent predictor of the manifest everyday functioning composite, t(70) = 1.03, p = .307, β = .139. Education was the only significant independent predictor of manifest everyday functioning impairment, t(70) = −2.01, p = .048, β = −.240, with lower education associated with a higher number of everyday functioning domains impaired. Additionally, UPSA-B scores were not related to any of the individual manifest functioning variables at the univariate level (all ps > .10, rs range .01–.10). UPSA-B scores were not associated with SF-36 physical health summary scores (rs = −.04, p = .705) or SF-36 mental health summary scores (rs = .02, p = .871).

Demographic, neuropsychological, and medical associations of UPSA-B in HIV

Demographic associations with UPSA-B in the HIV+ group

As shown in Table 2, UPSA-B scores were related to years of education within the HIV+ group (rs = .45, p < .0001). UPSA-B scores were not related to any other demographic variables listed in Table 2 (all ps > .10).

Neuropsychological associations with UPSA-B in the HIV+ group

UPSA-B scores were significantly positively correlated with composite raw scores of global cognition (rs = .47, p < .0001), attention and processing speed (rs = .49, p < .0001), learning (rs = .33, p = .0035), delayed memory (rs = .35, p = .0019), executive functions (rs = .33, p = .0030), verbal fluency (rs = .41, p = .0002), and motor skills (rs = .30, p = .0068).

Medical and HIV disease correlates of UPSA-B in the HIV+ group

In order to determine whether UPSA-B performance was explained by medical or HIV disease characteristic severity, we conducted Spearman’s rho correlations while accounting for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate. No HIV disease or medical variable (i.e., HCV) listed in Table 2 was significantly associated with UPSA-B scores (all ps > .03).

Discussion

Construct Validity of the UPSA-B in HIV

The purpose of the current study was to investigate the construct validity and utility of using the UPSA-B as a performance-based measure of functional capacity in HIV disease, and to determine the possible added utility of using the UPSA-B as a part of broader assessment (e.g., along with measures of manifest everyday functioning, other performance-based measures of functional capacity, neurocognitive functioning, etc.) of functioning in HIV disease. Our findings indicate that there is mixed support for the construct validity of the UPSA-B in a well-characterized sample of individuals with HIV disease. Specifically, classification accuracy using UPSA-B scores in predicting HAND versus normal cognition within HIV showed that the UPSA-B evidences moderate diagnostic validity. These results suggest that the UPSA-B may have potential benefit for when characterizing important neurocognitive deficits associated with HIV. Furthermore, results indicated that the UPSA-B showed moderate convergent validity with another measure of functional capacity previously validated in HIV (i.e., Medication Management Test; Patton et al., 2012) and with all neuropsychological domains assessed. However, the UPSA-B was unable to distinguish between HIV+HAND+ and the HIV- group, showed no associations with manifest functioning, and was not related to quality of life in HIV. These results indicate that there is mixed support for the UPSA-B as a performance-based measure of functional capacity in HIV. Thus, its utility in HIV requires additional investigation, as the current data do not necessarily support its systematic use in the context of a broader battery of neuropsychological and everyday functioning measures. The implications for the use of the UPSA-B in clinical and research settings for HIV disease are discussed further below.

The UPSA-B evidenced moderate diagnostic validity, which was associated with a medium-to-large effect size (Cliff’s d = −.41), in distinguishing between HIV+HAND- and HIV+HAND+ groups. Specifically, using cutpoint on the UPSA-B of ≤ 83, we determined an overall classification accuracy of 64% and an overall odds ratio of 4.08, which suggests that individuals scoring less than or equal to 83 on UPSA-B were nearly 4 times more likely to have HAND than individuals that scored above 83. However, the UPSA-B was relatively ineffective at differentiating between HIV+HAND+ and HIV− groups. This finding may be in part due to the high rate of comorbidities found in the HIV− group (e.g., 18% prevalence of hepatitis C virus [HCV] infection; see Table 1), even though previous studies have used similar approaches in comparing HAND and HIV− groups and have detected group-level differences (e.g., Woods et al., 2016). One possible explanation for the lack of a difference in UPSA-B performance between the HIV+HAND+ and HIV− groups is specifically the relatively high rate of HCV infection in individuals in the HIV− group compared to other HIV− “control” samples. HCV is associated with cognitive impairment in domains of attention, working memory, and processing speed (Forton et al., 2002; Hilsabeck, Hassanein, Carlson, Ziegler, & Perry, 2003) and impairment in activities of daily living and quality of life (Hilsabeck et al., 2003). While the matching of HCV rates across the 3 groups of the present study allowed us to make more reliable inferences into the effects of HIV and HAND on UPSA-B performance independent of HCV status, the high rates of HCV (and other comorbidities) in the HIV− group is nevertheless a limitation. However, post hoc analyses showed the HCV was not associated with UPSA-B scores in the HIV− group (p > .10), and no other comorbidities (i.e., neurocognitive impairment, affective disorders, current affective distress, substance use dependence) were related to UPSA-B scores in the HIV− group (all ps > .10). Even restricting our HAND group to only individuals diagnosed with MND did not change the equivocal performances between the HIV− group and the HIV+HAND+ group and was associated with a small effect size (p > .10; Cliff’s d = .31), which further suggests that the HIV− group is performing similarly even to a relatively moderately cognitively impaired group of HIV+ individuals. Future studies should expand upon the presently utilized exclusion criteria in order to exclude significant medical conditions to avoid potential confounding effects of such conditions. Regardless, the use of a comparison group, as opposed to a control group with few medical and mood comorbidities, is a potential limitation of the current study.

Diagnostic Validity of UPSA-B for Syndromic HAND

We found that UPSA-B scores differentiated between syndromic HAND (MND) and HIV+HAND− individuals. This finding offers further mixed support for the diagnostic validity of the UPSA-B, since we also would expect that HIV+HAND+ individuals with ANI (individuals without expected functional impairment) would perform more poorly on the UPSA-B compared to HIV+HAND+ individuals with MND, which was not observed. Since we did not observe any cases of HAD in our sample (the prevalence of HAD is estimated to be 1–2% [Heaton et al., 2010]), we were unable to determine how such individuals would perform on the UPSA-B, which is a limitation of the current study that should be addressed in future investigations with larger samples. Additionally, our use of ROC curve classification accuracy in such a small sample is a limitation of the present study, as our data possibly offer a less reliable description of the classification accuracy of the UPSA-B, and future studies should aim to utilize similar statistical methods in larger samples.

Convergent Validity of the UPSA-B in HIV

UPSA-B Convergence with MMT-R

We found evidence of strong convergent validity between the UPSA-B and another performance-based measure of everyday functioning (i.e., MMT-R). The MMT-R is moderately associated with neuropsychological functioning in HIV disease, is modestly associated with real-world adherence in immunocompromised individuals (Patton et al., 2012), and is sensitive in detecting syndromic HAND (Blackstone et al., 2012). While the present data are limited in predicting real-world outcomes such as medication adherence (NB. UPSA-B scores were not related to disease characteristics, a potential downstream indicator of adherence), the strong association between UPSA-B and MMT-R implicates the UPSA-B as being a potentially useful tool in identifying problems in functional capacity in as measured in the laboratory. A limitation of our study includes the use of a capacity-based task assessing medication management in order to investigate the convergent validity of the UPSA-B—a measure of financial and communication skills. However, our finding of a large association between the UPSA-B and the MMT-R may suggest that each of these face-valid measures of separable everyday functioning domains may be capturing a common everyday functioning ability.

UPSA-B Convergence with Manifest Everyday Functioning

The UPSA-B was not related to a manifest functioning variable consisting of employment status, iADL dependence, bADL dependence, physician rating of functioning, and a self-reported rating of functioning in the context of relevant disease and mood covariates. While previous studies have suggested that report-based ratings of manifest functioning (as is measured by this composite variable) may be unduly influenced by mood and insight (Thames, Becker et al., 2011; Thames, Kim et al., 2011), the present findings suggest that the UPSA-B is not related to report-based measures of everyday functioning. This is consistent with previous findings (Blackstone et al., 2012) but also diverges from other studies showing correspondence between report- and performance-based measures of everyday functioning (e.g., Heaton et al., 2004). Critically, the presently utilized composite of manifest everyday functioning has questionable content relatedness the UPSA-B, which measures financial and communication skills. Our utilization of measures of manifest everyday functioning with questionable content relatedness the UPSA-B (e.g., no manifest everyday functioning domains that comprehensively assess communications and finances) is a limitation of the current study. However, it also is possible that the UPSA-B and report-based manifest functioning assessments may be capturing everyday functioning performances differently for certain individuals who may experience different challenges in functioning in their everyday life. One aim of the present study was to determine the possible utility of the UPSA-B as a part of broader assessment of functioning in HIV disease. These data in general support the broad conceptual need for clinicians to consider multiple sources of data when considering functional status, including multiple methods of assessment across multiple domains of everyday function. For example, these data also call into question the broader conceptual ceiling effects of the UPSA-B, which consists primarily of relatively simple tasks such as counting change, dialing a phone number, writing a check, and remembering an appointment. Indeed, a potential limitation of the UPSA-B is the potential for psychometric ceiling effects, which in the current study may have limited our ability to detect a difference between HIV− and HIV+HAND− groups. As such, it may be important to consider more challenging functional activities in addition to those considered by UPSA-B when performing capacity-based assessments in the laboratory or clinic. Future studies should specifically aim to determine how cognitive and procedural demands of capacity-based measures such as the UPSA-B parallel the actual demands of everyday life, with future emphasis also placed on determining the specific associations between capacity and manifest measures of everyday functioning.

UPSA-B Convergence with Quality of Life

The UPSA-B was not related to important downstream effects that have been previously shown to be associated with everyday functioning in the real world (Moore et al., 2014; Woods et al., 2015), such as health or mental quality of life. This finding highlights a general trend in the present investigation suggesting that the UPSA-B may have limited utility in detecting important downstream effects commonly associated with HIV disease. In further support of this hypothesis, no disease or medical variables were related to the UPSA-B after controlling for multiple comparisons. These data also underscore the general limitations and benefits of performance-based measures that do not rely on report-based methods in general. Specifically, the present findings support the use of performance-based measures when attempting to determine capacity to perform a task in a structured environment free from the environmental demands of the real world.

UPSA-B Convergence with Neuropsychological Domains

All neuropsychological domains assessed in the current study were related to the UPSA-B. The effect sizes of these associations were medium-to-large in magnitude (rs range .30–.49) and suggest that there may be a requirement for intact global, domain-general cognitive function in order to successfully complete the UPSA-B. These findings stand in parallel to previous investigations showing reliable associations between UPSA-B performances and measures of cognition across clinical populations, particularly with composite domains of global cognition (Kaye et al., 2014; Keefe et al., 2011; Villegan et al., 2014). However, our findings also suggest that the UPSA-B may not be ideal for determining specific neurocognitive domains that may be underlying capacity deficits as measured in the laboratory. Even still, the multifaceted nature of everyday tasks that require multiple, parallel online cognitive systems may in part explain the lack of specificity between cognitive domains and UPSA-B performance. In other words, our lack of a finding of specific neurocognitive domains that relate to UPSA-B performance may suggest its correspondence with the complex nature of everyday tasks as performed in the real world.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to investigate the construct validity of the UPSA-B as a performance-based measure of functional capacity in HIV disease. The present study offers mixed support for the construct validity of the UPSA-B in HIV disease. Specifically, the UPSA-B appears to have potential benefit for characterizing functional capacity and cognitive changes often associated with HIV. However, the UPSA-B appears limited in its ability to predict the critical real-world (e.g., manifest functioning) and downstream effects (e.g., quality of life) of HIV disease. Future studies should aim to examine how face-valid tests of functional capacity in the laboratory such as the UPSA-B compare to tasks that are becoming increasingly common in everyday life, such as utilizing a credit cards, internet banking, and online medical records (e.g., Woods et al., 2016).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grants R01-MH073419, R21- MH098607 and P30-MH62512. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government. The authors thank Donald Franklin, Erin E. Morgan, Clint Cushman, and Stephanie Corkran for their help with data processing.

The San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program [HNRP] group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, and includes: Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Co-Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and J. Allen McCutchan, M.D.; Center Manager: Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Melanie Sherman; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Scott Letendre, M.D., Edmund Capparelli, Pharm.D., Rachel Schrier, Ph.D., Debra Rosario, M.P.H., Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), Mariana Cherner, Ph.D., Jennifer E. Iudicello, Ph.D., David J. Moore, Ph.D., Erin E. Morgan, Ph.D., Matthew Dawson; Neuroimaging Component: Terry Jernigan, Ph.D. (P.I.), Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D., Sarah L. Archibald, M.A., John Hesselink, M.D., Jacopo Annese, Ph.D., Michael J. Taylor, Ph.D.; Neurobiology Component: Eliezer Masliah, M.D. (P.I.), Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D., Ian Everall, FRCPsych., FRCPath., Ph.D. (Consultant); Neurovirology Component: Douglas Richman, M.D., (P.I.), David M. Smith, M.D.; International Component: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., (P.I.); Developmental Component: Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; (P.I.), Stuart Lipton, M.D., Ph.D.; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (P.I.); Data Management Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman (Data Systems Manager); Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph.D., Reena Deutsch, Ph.D., Anya Umlauf, M.S.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, … Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Army Individual Test Battery. Manual of directions and scoring. Washington, DC: War Department, Adjutant General’s Office; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher K, Sivan AB. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. 3. Iowa City, IA: AJA Associates; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone K, Moore DJ, Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Woods SP, Clifford DB … CNS HIV Antiretroviral Therapy Effects Research (CHARTER) Group. Diagnosing symptomatic HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: self-report versus performance-based assessment of everyday functioning. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2012;18(1):79–88. doi: 10.1017/S135561771100141X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone Kaitlin, Iudicello JE, Morgan EE, Weber E, Moore DJ, Franklin DR … Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center Group. Human immunodeficiency virus infection heightens concurrent risk of functional dependence in persons with long-term methamphetamine use. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2013;7(4):255–263. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318293653d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RH. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test - Revised. Odessa, Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Benedict RHB. Professional manual. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. Hopkins verbal learning test-revised. [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, Conover E, Marcotte TD, Grant I … HNRC Group. Predictive validity of global deficit scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004;26(3):307–319. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelune GJ, Heaton RK, Lehman RA. Neuropsychological and personality correlates of patients’ complaints of disability. In: Tarter RE, editor. Advances in clinical neuropsychology. 3. New York: Plenum; 1986. pp. 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu AW. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS care. 2000;12(3):255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle KL, Morgan EE, Weber E, Woods SP HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group. Time estimation and production in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2015;21(2):175–181. doi: 10.1017/S1355617715000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle K, Weber E, Atkinson JH, Grant I, Woods SP HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group. Aging, prospective memory, and health-related quality of life in HIV infection. AIDS and behavior. 2012;16(8):2309–2318. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0121-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dray-Spira R, Persoz A, Boufassa F, Gueguen A, Lert F, Allegre T … Primo Cohort Study Group. Employment loss following HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapies. European Journal of Public Health. 2006;16(1):89–95. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forton DM, Thomas HC, Murphy CA, Allsop JM, Foster GR, Main J, … Taylor-Robinson SD. Hepatitis C and cognitive impairment in a cohort of patients with mild liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2002;35(2):433–439. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi NS, Skolasky RL, Peters KB, Moxley RT, Creighton J, Roosa HV, … Sacktor N. A comparison of performance-based measures of function in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Journal of Neurovirology. 2011;17(2):159–165. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0023-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladsjo JA, Schuman CC, Evans JD, Peavy GM, Miller SW, Heaton RK. Norms for letter and category fluency: Demographic corrections for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1999;6:147–178. doi: 10.1177/107319119900600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman AA, Foley JM, Ettenhofer ML, Hinkin CH, Van Gorp WG. Functional consequences of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment. Neuropsychology Review. 2009;19(2):186–203. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9095-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould F, McGuire LS, Durand D, Sabbag S, Larrauri C, Patterson TL, … Harvey PD. Self-assessment in schizophrenia: Accuracy of evaluation of cognition and everyday functioning. Neuropsychology. 2015;29(5):675–682. doi: 10.1037/neu0000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronwall DM. Paced auditory serial-addition task: A measure of recovery from concussion. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1977;44:367–375. doi: 10.2466/pms.1977.44.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F … CHARTER Group. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, Sadek J, Moore DJ, Bentley H … HNRC Group. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2004;10(3):317–331. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilsabeck RC, Hassanein TI, Carlson MD, Ziegler EA, Perry W. Cognitive functioning and psychiatric symptomatology in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2003;9(6):847–854. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703960048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Hardy DJ, Mason KI, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Lam MN, Stefaniak M. Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance abuse. AIDS (London, England) 2004;18(Suppl 1):S19–25. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200418001-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat R, Woods SP, Cameron MV, Iudicello JE HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group. Apathy is associated with lower mental and physical quality of life in persons infected with HIV. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2015.1131998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemo-therapeutic agents in cancer. In: Maclead CM, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1949. pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye JL, Dunlop BW, Iosifescu DV, Mathew SJ, Kelley ME, Harvey PD. Cognition, functional capacity, and self-reported disability in women with posttraumatic stress disorder: examining the convergence of performance-based measures and self-reports. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;57:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RSE, Fox KH, Harvey PD, Cucchiaro J, Siu C, Loebel A. Characteristics of the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery in a 29-site antipsychotic schizophrenia clinical trial. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;125(2–3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kløve H. Grooved pegboard. Indiana: Lafayette Instruments; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Kongs SK, Thompson LL, Iverson GL, Heaton RK. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test - 64 Card Computerized Version. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leifker FR, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Determinants of everyday outcomes in schizophrenia: the influences of cognitive impairment, functional capacity, and symptoms. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;115(1):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani LM, Teixeira AL, Salgado JV. Functional capacity: a new framework for the assessment of everyday functioning in schizophrenia. Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil: 1999) 2015;37(3):249–255. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte TD, Wolfson T, Rosenthal TJ, Heaton RK, Gonzalez R, Ellis RJ … HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center Group. A multimodal assessment of driving performance in HIV infection. Neurology. 2004;63(8):1417–1422. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000141920.33580.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Bowie CR, Harvey PD, Twamley EW, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Usefulness of the UCSD performance-based skills assessment (UPSA) for predicting residential independence in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42(4):320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Depp CA, Bowie CR, Harvey PD, McGrath JA, Thronquist MH, … Patterson TL. Sensitivity and specificity of the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA-B) for identifying functional milestones in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;132(2–3):165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Harvey PD, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Development of a brief scale of everyday functioning in persons with serious mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33(6):1364–1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Fazeli PL, Jeste DV, Moore DJ, Grant I, Woods SP HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group. Successful cognitive aging and health-related quality of life in younger and older adults infected with HIV. AIDS and behavior. 2014;18(6):1186–1197. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0743-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EE, Iudicello JE, Weber E, Duarte NA, Riggs PK, Delano-Wood L … HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group. Synergistic effects of HIV infection and older age on daily functioning. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2012;61(3):341–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826bfc53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson AK, Helldin L, Hjärthag F, Norlander T. Psychometric properties of a performance-based measurement of functional capacity, the UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment - Brief version. Psychiatry Research. 2012;197(3):290–294. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osowiecki DM, Cohen RA, Morrow KM, Paul RH, Carpenter CC, Flanigan T, Boland RJ. Neurocognitive and psychological contributions to quality of life in HIV-1-infected women. AIDS (London, England) 2000;14(10):1327–1332. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27(2):235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton DE, Woods SP, Franklin D, Cattie JE, Heaton RK, Collier AC, … Grant I. Relationship of Medication Management Test-Revised (MMT-R) performance to neuropsychological functioning and antiretroviral adherence in adults with HIV. AIDS and behavior. 2012;16(8):2286–2296. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0237-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Corporation. WAIS-III WMS-III technical manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Corporation. Manual for the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) San Antonio: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shen JM, Blank A, Selwyn PA. Predictors of mortality for patients with advanced disease in an HIV palliative care program. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2005;40(4):445–447. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000185139.68848.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard DP, Woods SP, Bondi MW, Gilbert PE, Massman PJ, Doyle KL HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program Group. Does Older Age Confer an Increased Risk of Incident Neurocognitive Disorders Among Persons Living with HIV Disease? The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2015;29(5):656–677. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2015.1077995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS and behavior. 2006;10(3):227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames AD, Becker BW, Marcotte TD, Hines LJ, Foley JM, Ramezani A, … Hinkin CH. Depression, cognition, and self-appraisal of functional abilities in HIV: an examination of subjective appraisal versus objective performance. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2011;25(2):224–243. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2010.539577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames AD, Kim MS, Becker BW, Foley JM, Hines LJ, Singer EJ, … Hinkin CH. Medication and finance management among HIV-infected adults: the impact of age and cognition. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2011;33(2):200–209. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.499357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi V, Balestra P, Galgani S, Murri R, Bellagamba R, Narciso P, … Wu AW. Neurocognitive performance and quality of life in patients with HIV infection. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2003;19(8):643–652. doi: 10.1089/088922203322280856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE, Fazeli PL, Ball DA, Slater LZ, Ross LA. Cognitive functioning and driving simulator performance in middle-aged and older adults with HIV. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC. 2014;25(2):e11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velligan DI, Fredrick M, Mintz J, Li X, Rubin M, Dube S, … Marder SR. The reliability and validity of the MATRICS functional assessment battery. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40(5):1047–1052. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner G, Miller LG. Is the influence of social desirability on patients’ self-reported adherence overrated? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2004;35(2):203–204. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200402010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36® Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: New England Medical Center, The Health Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Iudicello JE, Morgan EE, Cameron MV, Doyle KL, Smith TV … HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program HNRP Group. Health-Related Everyday Functioning in the Internet Age: HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders Disrupt Online Pharmacy and Health Chart Navigation Skills. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology: The Official Journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists. 2016;31(2):176–185. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acv090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Weinborn M, Li YR, Hodgson E, Ng ARJ, Bucks RS. Does prospective memory influence quality of life in community-dwelling older adults? Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition. Section B, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition. 2015;22(6):679–692. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2015.1027651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI, version 2.1) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]