Abstract

Since 2013, the Hospital-based Influenza Morbidity and Mortality (HIMM) surveillance system began a H7N9 influenza surveillance scheme for returning travelers in addition to pre-existing emergency room (ER)-based influenza-like illness (ILI) surveillance and severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) surveillance. Although limited to eastern China, avian A/H7N9 influenza virus is considered to have the highest pandemic potential among currently circulating influenza viruses. During the study period between October 1st, 2013 and April 30th, 2016, 11 cases presented with ILI within seven days of travel return. These patients visited China, Hong Kong, or neighboring Southeast Asian countries, but none of them visited a livestock market. Seasonal influenza virus (54.5%, 6 among 11) was the most common cause of ILI among returning travelers, and avian A/H7N9 influenza virus was not detected during the study period.

Keywords: Influenza, H7N9 Virus, Influenza-like Illness, Surveillance

Graphical Abstract

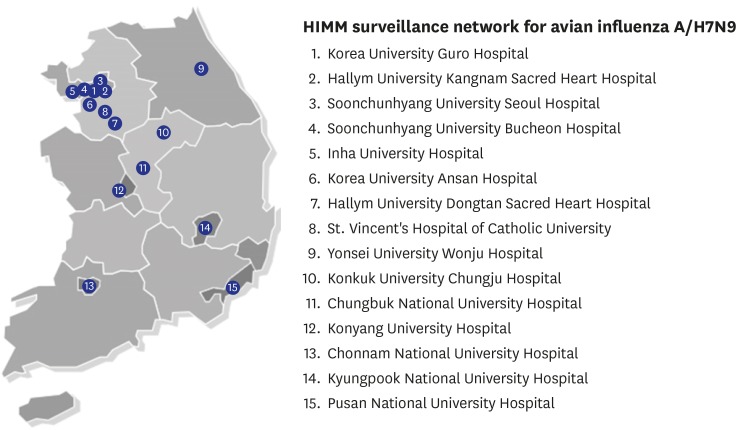

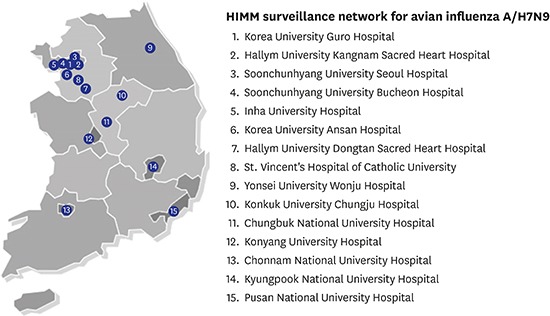

In 2011, the Hospital-based Influenza Morbidity and Mortality (HIMM) surveillance system was established in Korea.1 Initially, the HIMM surveillance system was composed of two kinds of surveillance schemes: emergency room (ER)-based influenza-like illness (ILI) surveillance and severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) surveillance.1,2 In early 2013, the novel avian influenza A/H7N9 virus emerged and persistently circulated in China. Given its geographically close location and frequent travel to China, experts have expressed concern about domestic inflow of avian A/H7N9 influenza virus to Korea. Thus, an additional surveillance scheme was added to the HIMM surveillance system for the early detection of novel avian A/H7N9 influenza virus from travel returners. In addition to 10 hospitals (Korea University Guro Hospital, Korea University Ansan Hospital, St. Vincent's Hospital of The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Pusan National University Hospital, Chonnam National University Hospital, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Yonsei University Wonju Hospital, Inha University Hospital, and Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital) participating in ER-ILI and SARI surveillance, five 500–1,000 bed hospitals (Konyang University Hospital, Konkuk University Chungju Hospital, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, Soonchunhyang University Bucheon Hospital, and Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital) were further included in the A/H7N9 influenza surveillance scheme (Fig. 1). This study was approved by the ethics committee of each institution and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices.

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of hospitals participating in A/H7N9 HIMM surveillance.

HIMM = Hospital-based Influenza Morbidity and Mortality.

Foreign travel information was collected from the patients with ILI. If the patient visited China, Hong Kong, or neighboring Southeast Asian countries within seven days before ILI development, respiratory specimens were collected using virus transport medium after informed consent. ILI was defined as sudden onset of fever (> 37.8°C) accompanied by at least one respiratory symptom (cough and/or sore throat).1 After enrollment, a rapid influenza antigen test was administered for seasonal influenza viruses, and respiratory specimens were transported to the central laboratory (Korea University Guro Hospital). All cases were tested for A/H7N9 influenza virus using the World Health Organization (WHO) real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocol.3 At the same time, the presence of seasonal influenza virus (A/B), respiratory syncytial virus (A/B), parainfluenza virus (type 1–4), adenovirus, human rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, human coronavirus (hCoV-229E, hCoV-OC43), human bocavirus, and enterovirus was determined using the Seeplex® RV15 PCR assay (Seegene Inc., Seoul, Korea) as described previously.4 For test-negative cases, real-time PCR assays were conducted to detect enterovirus D68, WU polyomavirus, KI polyomavirus, parechovirus (type 1, 3, and 6), and pteropine orthoreovirus using primers presented in Table 1.5,6,7,8

Table 1. Primer sequences for real-time polymerase chain reaction of respiratory viruses.

| Respiratory viruses | Target | Primer sequences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterovirus D68 | VP1 | Forward | TGT TCC CAC GGT TGA AAA CAA |

| Reverse | TGT CTA GCG TCT CAT GGT TTT CAC | ||

| Wu polyomavirus | VP1 | Forward | AAC CAG GAA GGT CAC CAA GAA G |

| Reverse | TCT ACC CCT CCT TTT CTG ACT TGT | ||

| KI polyomavirus | VP2–3 | Forward | CTA TCC CTG AAT ACC AGT TGG AAA C |

| Reverse | GTA TGA CGC GAC AAG GTT GAA G | ||

| Parechovirus type 1 | VP1 | Forward | TCG TGG GGT TCA CAA ATG GA |

| Reverse | TCC TGA GCC GAT GTT AAG CC | ||

| Parechovirus type 3 | VP1 | Forward | GAC AAC ATC TTT GGT AGA GCT TGG T |

| Reverse | TTT TGC CTC CAG GTA TCT CCA T | ||

| Parechovirus type 6 | VP1 | Forward | CTG AGG ACG GTT AGG GAC AC |

| Reverse | ACG ATT TTG CGA ACG TGG TG | ||

| Pteropine orthoreovirus | S2 | Forward | CCA CGA TGG CGC GTG CCG TGT TCG A |

| Reverse | ACG TAG GGA GGC GCA CGA GGT GGA | ||

During the study period between October 1st, 2013 and April 30th, 2016, 11 patients presented with ILI within seven days from travel return (Table 2). Seven (63.6%) of the 11 patients visited eastern China where avian A/H7N9 influenza virus was prevalent (Table 2). The other four patients visited Hong Kong (n = 2), Malaysia (n = 1), Cambodia (n = 1), and Vietnam (n = 1). Seasonal influenza virus was the most common cause of ILI among returning travelers. Seasonal influenza viruses were isolated from six patients (54.5%): four with A/H1N1 and two with A/H3N2 influenza viruses (Table 2). No other respiratory viruses, including avian A/H7N9 influenza virus, were detected. As previously reported,9 the majority of H7N9 human cases developed after visiting live poultry markets in China; in this study, none of the eleven patients visited a livestock market while they travelled abroad (Table 2). Since the first report of human A/H7N9 cases in China in February 2013, the virus has been detected in domestic poultry exclusively in eastern China with limited detection in migratory wild birds according to surveillance studies.9,10 Thus, contrary to avian A/H5N1 influenza viruses that have spread worldwide, avian H7N9 influenza viruses are, at least currently, confined within China. Actually, less than 5% of human A/H7N9 cases have been reported in countries other than China, including Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Canada, and all of these patients travelled to China prior to illness onset.9,11 However, H7N9 influenza viruses are genetically more human-adapted compared to H5N1 influenza viruses, and H7N9 influenza viruses are reported to cause human infection even after casual contact such as walking through a livestock market without direct close contact.9,10 In a similar time frame, the incidence of H7N9 human infection was 10 times higher than that of H5N1 infection.9 Although limited to eastern China as of yet, avian H7N9 influenza virus is considered to have the highest pandemic potential among currently circulating influenza viruses.12 Based on assessment using the influenza risk assessment tool (IRAT), the risk for H7N9 influenza virus to achieve sustained human-to-human transmission was in the moderate risk category, while the risk of public health impact was in the high-moderate risk range.12 The geographic spread and pandemic risk might change over time with viral evolution and host adaptation. Thus, the H7N9 influenza surveillance system should be maintained on an ongoing basis and strengthened based on repetitive risk assessment. Rapid and timely reporting is the key element of the HIMM surveillance system, thereby enabling prompt response to public health threats from novel respiratory pathogens. Rapid detection should lead to the identification and characterization of pathogens with respect to transmissibility, virulence, and host susceptibility in the general population.

Table 2. List of returning travelers who presented with influenza-like illness.

| No. | Age | Sex | Year | Month | Travel areas | Livestock market visit | Isolated virus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | Female | 2013 | October | Hunan Sheng, China | No | Influenza A/H1N1 |

| 2 | 22 | Female | 2013 | November | Hong Kong | No | Influenza A/H3N2 |

| 3 | 34 | Male | 2014 | January | Guangzhou and Shanghai, China | No | - |

| 4 | 25 | Male | 2014 | January | Siem Reap, Cambodia | No | Influenza A/H1N1 |

| 5 | 38 | Male | 2014 | January | Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia and Hong Kong | No | - |

| 6 | 50 | Male | 2014 | February | Jilin Sheng, China | No | - |

| 7 | 62 | Male | 2014 | June | Hunan Sheng, China | No | - |

| 8 | 44 | Female | 2015 | March | Beijing, China | No | - |

| 9 | 62 | Female | 2015 | October | Henan Sheng, China | No | Influenza A/H3N2 |

| 10 | 40 | Male | 2016 | February | Shanghai, China | No | Influenza A/H1N1 |

| 11 | 68 | Male | 2016 | March | Hanoi, Vietnam | No | Influenza A/H1N1 |

In this study, no human case of A/H7N9 influenza infection was found in Korea among travelers. However, Korea is geographically close to China, and travels to China are common. In addition, there is a possibility of A/H7N9 influenza influx due to increasing trade between Korea and China. Of note, human A/H7N9 influenza infection cases increased in number and the epidemic areas were extended to the northern and western regions (Beijing, Jilin, Liaoning, Gansu, Chongqing, Guizhou, and Sichuan) of China during the 2016–2017 influenza season. During the fifth epidemic wave since October 2016, the number of human cases with avian influenza A/H7N9 infection was greater than the numbers of those reported in earlier waves.13 Accordingly, the risk of human A/H7N9 influenza infection influx has substantially increased in Korea. Therefore, the Korean A/H7N9 influenza surveillance system should be strengthened and maintained. Since the A/H7N9 influenza infection is accompanied by pneumonia in most cases, it is necessary to expand the surveillance system by including larger number of university hospitals.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIP) (NRF-2016R1A5A1010148) and grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R & D Project of the Ministry of Health and Welfare of the Republic of Korea (No. A103001).

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Song JY, Noh JY, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ. Data curation: Noh JY, Lee HS. Investigation: Song JY, Noh JY, Lee J, Woo HJ, Lee JS, Wie SH, Kim YK, Jeong HW, Kim SW, Lee SH, Park KH, Kang SH, Kee SY, Kim TH, Choo EJ, Choi WS, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ. Writing - original draft: Song JY, Kim WJ. Writing - review & editing: Song JY, Noh JY, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ.

References

- 1.Song JY, Cheong HJ, Choi SH, Baek JH, Han SB, Wie SH, et al. Hospital-based influenza surveillance in Korea: hospital-based influenza morbidity and mortality study group. J Med Virol. 2013;85(5):910–917. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang SH, Cheong HJ, Song JY, Noh JY, Jeon JH, Choi MJ, et al. Analysis of risk factors for severe acute respiratory infection and pneumonia and among adult patients with acute respiratory illness during 2011–2014 influenza seasons in Korea. Infect Chemother. 2016;48(4):294–301. doi: 10.3947/ic.2016.48.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Real-time RT-PCR protocol for the detection of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. [Updated 2013]. [Accessed September 10, 2017]. http://www.who.int/influenza/gisrs_laboratory/cnic_realtime_rt_pcr_protocol_a_h7n9.pdf.

- 4.Seo YB, Song JY, Choi MJ, Kim IS, Yang TU, Hong KW, et al. Etiology and clinical outcomes of acute respiratory virus infection in hospitalized adults. Infect Chemother. 2014;46(2):67–76. doi: 10.3947/ic.2014.46.2.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selvaraju SB, Nix WA, Oberste MS, Selvarangan R. Optimization of a combined human parechovirus-enterovirus real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay and evaluation of a new parechovirus 3-specific assay for cerebrospinal fluid specimen testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(2):452–458. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01982-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taniguchi S, Maeda K, Horimoto T, Masangkay JS, Puentespina R, Jr, Alvarez J, et al. First isolation and characterization of pteropine orthoreoviruses in fruit bats in the Philippines. Arch Virol. 2017;162(6):1529–1539. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuypers J, Campbell AP, Guthrie KA, Wright NL, Englund JA, Corey L, et al. WU and KI polyomaviruses in respiratory samples from allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(10):1580–1588. doi: 10.3201/eid1810.120477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiche J, Böttcher S, Diedrich S, Buchholz U, Buda S, Haas W, et al. Low-level circulation of enterovirus D68-associated acute respiratory infections, Germany, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(5):837–841. doi: 10.3201/eid2105.141900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bui C, Bethmont A, Chughtai AA, Gardner L, Sarkar S, Hassan S, et al. A systematic review of the comparative epidemiology of avian and human influenza A H5N1 and H7N9 - lessons and unanswered questions. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2016;63(6):602–620. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millman AJ, Havers F, Iuliano AD, Davis CT, Sar B, Sovann L, et al. Detecting spread of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus beyond China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(5):741–749. doi: 10.3201/eid2105.141756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skowronski DM, Chambers C, Gustafson R, Purych DB, Tang P, Bastien N, et al. Avian influenza A(H7N9) virus infection in 2 travelers returning from China to Canada, January 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(1):71–74. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trock SC, Burke SA, Cox NJ. Development of framework for assessing influenza virus pandemic risk. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(8):1372–1378. doi: 10.3201/eid2108.141086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus ??China. [Updated 2017]. [Accessed September 10, 2017]. http://www.who.int/csr/don/09-may-2017-ah7n9-china/en/