Abstract

Microvascular decompression (MVD) is a widely used, safe, and effective treatment for trigeminal neuralgia (TGN). However, the extent of application of this therapeutic method and its outcomes in Japan are currently unclear. To address these questions, the authors analyzed the use of MVD for the treatment of TGN during the 33-month period from July 2010 to March 2013, using data contained in the Diagnosis Procedure Combination database. The analysis revealed that MVD was used for the treatment of TGN in 1619 cases (608 men, 1011 women), with approximately 1.66 times more women treated than men. MVD for TGN was most frequently performed in individuals 60 to 79 years of age; of particular note was the remarkable increase in the number of women in this particular category. The overall number of procedures performed per 100,000 population/year in Japan was 0.46. The number of procedures was larger in prefectures with higher populations, with a tendency toward a higher number of MVD procedures performed in the area designated West than in the East. Discharge outcomes indicated that cure and improvement were achieved in 97.6% of cases, with a mortality rate of 0.2%, and no differences in discharge outcomes between men and women. The mean length of hospital stay in patients undergoing MVD for TGN was 14.8 days. This analysis revealed discernable trends in the use of MVD for the treatment of TGN in Japan.

Keywords: trigeminal neuralgia, microvascular decompression, big data

Introduction

Trigeminal neuralgia (TGN) is characterized by paroxysmal attacks of sharp, electric-like pain in the region corresponding to the distribution of the trigeminal nerve.1–2) Medical therapy for TGN includes carbamazepine, baclofen, and gabapentin. The initial response rate for this therapy is approximately 80%, which declines to less than 50% over time. Moreover, medical therapy may be discontinued due to drug allergy or a liver function disorder.3–7) Microvascular decompression (MVD) is the recognized method of choice to definitively cure TGN if medical treatment fails to provide sufficient relief. MVD has proven long-term efficacy when performed at specialized centers,8) and offers significant advantages over alternative treatments such as radiofrequency rhizotomy and stereotaxic radiosurgery.9,10)

However, there have been no studies investigating the use of MVD for TGN in Japan, and details regarding its current status and outcomes are unclear. The Japanese case-mix classification system, namely, the Diagnosis Procedure Combination (DPC) database, can be used to standardize medical profiling and payment.11–14) Japanese case-mix projects based on the DPC system were introduced to 82 academic hospitals (the National Cancer Center, the National Cardiovascular Center, and 80 university hospitals) in 2003.11–14) According to the administrative database of the DPC system, the number of acute care hospitals has increased. Enormous amounts of inpatient data are collected annually, covering approximately 90% of the total acute care inpatient hospitalizations.11–14) Therefore, the data in the DPC system should clearly reflect the state of medical care in Japan at the population level. This system collects important data during hospitalization, in addition to the characteristics of the unique reimbursement system. Each patient’s financial data, claim information, and discharge summary (including principal diagnosis, complications, and comorbidities during hospitalization) are thoroughly recorded in the DPC administrative database. These data are coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code. Additionally, this administrative database contains comprehensive medical information, including all interventional or surgical procedures, medications, and devices that have been indexed in the original Japanese code. To optimize the accuracy of the recorded diagnoses, physicians are obligated to record diagnoses based on patient medical records.

The purpose of this retrospective study was to analyze data from this Japanese national administrative database to investigate the present use patterns of MVD for the treatment of TGN in Japan.

Methods

Data source

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) in Japan initiated and has overseen the original case-mix program (i.e., the DPC project) since 2003. Under the scheme, MHLW gathers DPC-related data from all participating institutions (1863 hospitals in 2014). This database contains clinical data as well as claims data for the date, cost, and quantity of medical care items used. Data from hospitals are gathered and merged into a standardized electronic format defined by the MHLW. Although this database is useful for various types of medical research, MHLW does not permit its use for such purposes.

Aside from the MHLW’s DPC project, the DPC Research Institute gathers DPC-related data from contracted hospitals to facilitate DPC-based health research. In this study, we used inpatient data for the 33-month period from July 1, 2010 to March 31, 2013. All the institutions and hospitals that provided detailed data granted permission for the use of these data, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical Care and Research of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu, Japan.

Patients

Information from 3076 patients with TGN (ICD-10 code G 50.0) were collected from 1222 of 1774 DPC-participating institutions, accounting for approximately 69% of all DPC data for the 33-month period from July 1, 2010 to March 31, 2013. Of the 1222 facilities, 850 were associated with departments of neurosurgery and 321 were performing MVD for TGN during the period when data were collected. Patients who had not undergone MVD for TGN (n = 1457) were excluded; therefore, 1619 patients were allocated for analysis. The variables extracted from the DPC database included patient age and sex, residential area, discharge status, and the length of hospital stay.

Furthermore, 47 prefectures were categorized into 8 distinct districts as follows: Hokkaido (Hokkaido); Tohoku (Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, Akita, Yamagata, and Fukushima); Kanto (Ibaraki, Tochigi, Gunma, Saitama, Chiba, Tokyo, and Kanagawa); Chubu (Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa, Fukui, Yamanashi, Nagano, Gifu, Shizuoka, and Aichi); Kinki (Mie, Shiga, Nara, Wakayama, Kyoto, Osaka, and Hyogo); Chugoku (Okayama, Hiroshima, Tottori, Shimane, and Yamaguchi); Shikoku (Kagawa, Tokushima, Ehime, and Kochi); and Kyushu (Fukuoka, Saga, Nagasaki, Oita, Kumamoto, Miyazaki, Kagoshima, and Okinawa). Furthermore, the Hokkaido, Tohoku, Kanto, and Chubu districts were categorized as the “East area”, and the Kinki, Chugoku and Kyushu districts as the “West area”. The number of MVD treatments for TGN per 100,000 population/year in each district and area were calculated using 2010 national census data.

Statistical analysis

The t-test was used to compare differences between the numbers of MVD procedures performed in each area. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM Statistics 22); P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

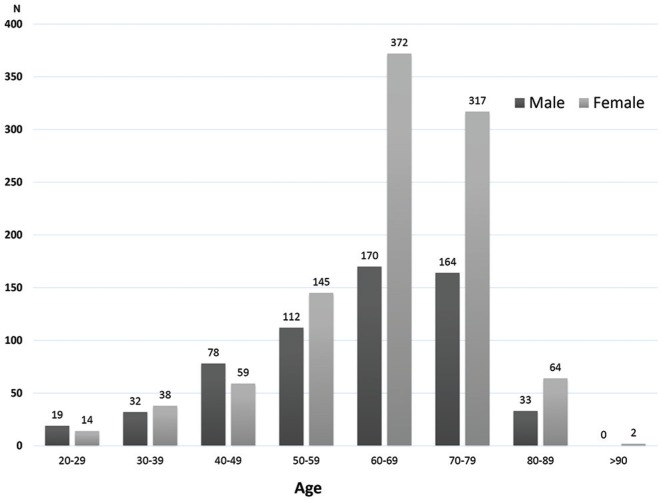

Analysis of the DPC data revealed that from July 1, 2010 to March 31, 2013, MVD was used for the treatment of TGN in 1619 cases (608 men, 1011 women) in DPC-participating facilities in Japan. The number of women treated using MVD was 1.66 times greater than the number of men who were treated. Overall, MVD for TGN was most frequently performed in patients in their 60s and 70s. Of particular note was the remarkable increase in the number of women in this particular age range (60–79 years of age) (Fig. 1). The female/male ratio of patients was 1.57 in those in their 20s to 80s and 2.06 for patients in their 60s (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Number of microvascular decompression (MVD) procedures for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia during the 33-month period from July 2010 to March 2013 in each age group. There were 1619 cases in total, including 608 men and 1011 women. The number of women was 1.66 times higher than the number of men. The number of women treated demonstrated a remarkable increase in those 60 to 79 years of age.

Table 1.

The number of male and female patients undergoing microvasculature decompression for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia

| Age at microvascular decompression treatment | Overall treatment rate per 100,000/year | Male treatment rate per 100,000/year | Female treatment rate per 100,000/year | Treatment rate per 100,000/year Female:Male ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–29 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.76:1 |

| 30–39 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 1.22:1 |

| 40–49 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.76:1 |

| 50–59 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 1.28:1 |

| 60–69 | 1.08 | 0.70 | 1.44 | 2.06:1 |

| 70–79 | 1.36 | 1.03 | 1.62 | 1.58:1 |

| 80–89 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 1.09:1 |

| Total | 0.57 | 0.44 | 0.69 | 1.57:1 |

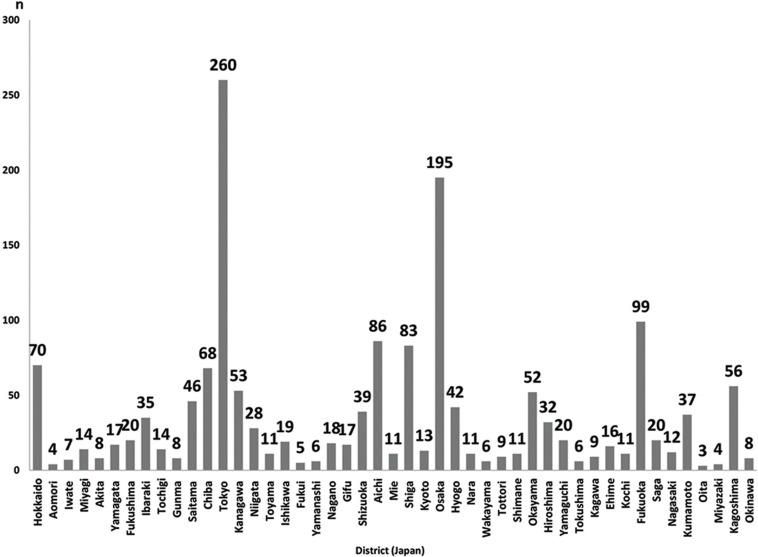

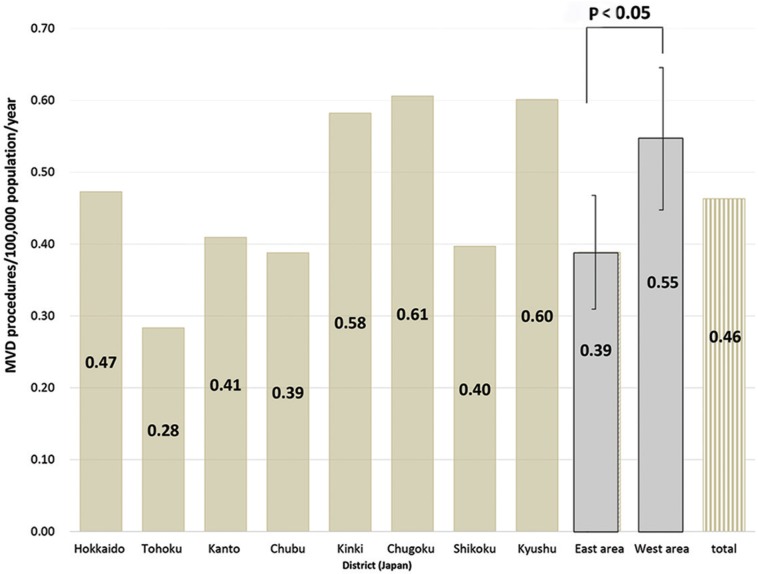

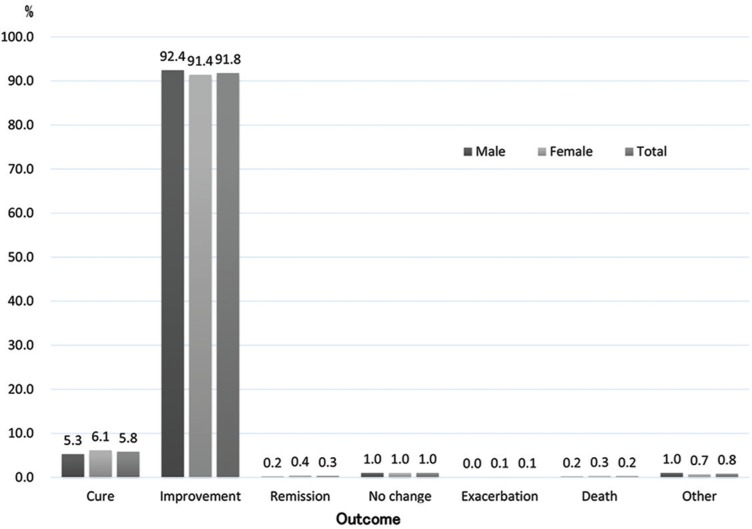

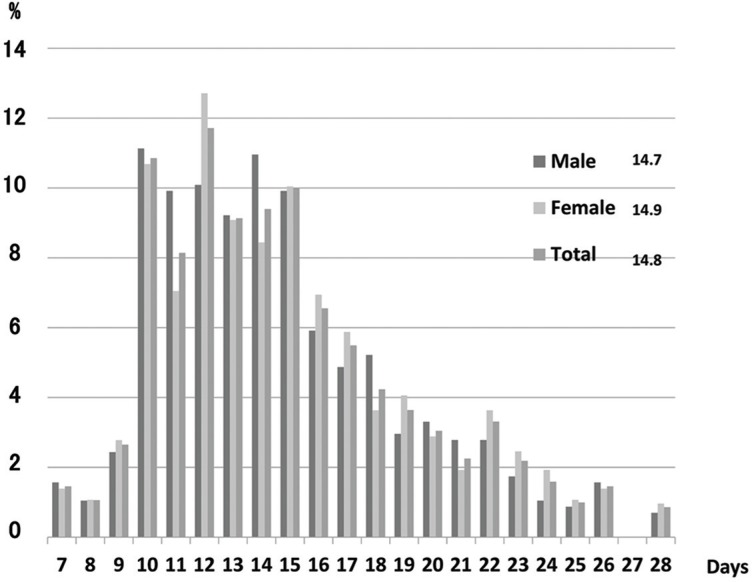

The highest number of MVD procedures were performed in the Tokyo prefecture (260 cases/33 months), and the number of MVD treatments was larger in prefectures with higher populations (Fig. 2). In Japan, the overall number of MVD procedures performed for the treatment of TGN per 100,000 population/year was 0.46 and, across the 8 districts, was as follows: Hokkaido, 0.47; Tohoku, 0.28; Kanto, 0.41; Chubu, 0.39; Kinki, 0.58; Chugoku, 0.61; Shikoku, 0.40; and Kyushu, 0.60. The number of MVD procedures performed in the West area was higher than in the East area (P < 0.05), especially in the Tohoku district, where the number of MVD procedures performed was lower than one-half of the highest number documented in the Chugoku and Kyushu districts (Fig. 3). Regarding discharge outcomes, the rate of “cure” was 5.8% and the rate of “improvement” was 91.8%, and the mortality was 4 of 1619 cases (0.2%). There was no apparent difference in discharge outcomes between men and women (Fig. 4). The mean length of hospital stay in patients undergoing MVD for TGN was 14.8 years (men, 14.7 days; women, 14.9 days) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

The number of cases of microvascular decompression for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia performed during the 33-month period from July 2010 to March 2013 in each prefecture (Japan). Tokyo had the highest number (260 cases), Osaka had 195 cases. Microvascular decompression was more frequently performed in prefectures with larger populations.

Fig. 3.

The number of patients undergoing microvascular decompression for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia per 100,000 population/year was compared among 8 districts and 2 areas (East and West) of Japan. Overall, 0.46 patients/100,000 population/year were treated. Among the districts, Tohoku had the lowest number (0.28 cases/100,000 population/year); moreover, the number of microvascular decompression procedures performed in the designated West area was higher than in the East area (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Discharge outcomes in patients undergoing microvascular decompression for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Outcomes were assessed as cure, improvement, remission, no change, exacerbation, death, and other conditions. Patients who experienced cure, improvement, or remission accounted for 97.9% of the study population; death occurred in 0.2% of patients.

Fig. 5.

Length of hospital stay in patients undergoing microvascular decompression for the treatment of hemifacial spasm. Overall, the mean length of hospital stay was 14.8 days. No difference in the length of stay was observed between men and women.

Discussion

The use of MVD for the treatment of TGN has been investigated in single- and multicenter studies; however, few investigations have been based on a national database, such as the DPC database8,15–19). Using DPC data, we analyzed the use of MVD for the treatment of TGN during the 33-month period from July 2010 to March 2013 in terms of the number of MVD procedures performed, regions where it was performed, length of hospital stay, and discharge outcomes. However, not all medical institutions in Japan contribute to the DPC database, enormous amounts of inpatient data collected annually and cover approximately 90% of total acute care inpatient hospitalizations. In 2012, data were collected from 1222 of 1774 DPC-participating institutions, accounting for approximately 69% of all DPC data. The data obtained for this study, therefore, should have accurately reflected trends in the use of MVD for the treatment of TGN in Japan for the period analyzed.

According to the DPC data, MVD for TGN had been performed in Japan at a male-to-female ratio of 1:1.66 and most frequently performed in patients in their 60s and 70s. In the literature, the morbidity rate in patients with TGN is reported to be 5.7/100,000 population in women and 2.5/100,000 population in men, corresponding to a sex ratio of 1.74:1, with both men and women experiencing high rates of morbidity after 50 years of age.20) Therefore, it is believed that the male-to-female treatment ratio and peak age in patients undergoing MVD is a reflection of the morbidity rates for TGN in men and women. This tendency for MVD was reflected equally for hemifacial spasm; the use of MVD in Japan is significantly affected by the morbidity of the disease.21) On the other hand, MVD is more frequently performed in elderly people 70 years or older for TGN than for hemifacial spasm. This may be partly due to the fact that, during this study period, whereas gamma knife treatment for TGN was not covered by insurance, botulinum therapy for HFS was, as well the possibility that indication of MVD for elderly patients is becoming more widespread because TGN has a more detrimental effect on patients’ activities of daily living (ADL).

Regarding the number of MVD procedures performed per 100,000 population/year in each district, the Tohoku district had the lowest number (0.28), which was approximately one-half of the highest number observed in the Chugoku and Kyushu districts. The number of MVD procedures performed in the designated West area was higher than in the East area (P < 0.05). We believe that this difference can be attributed to a trend toward surgical treatment of TGN in the West area, as opposed to a trend toward conservative therapy in the East area. However, DPC data do not provide information about the status of conservative therapy administered at outpatient clinics, which may affect the frequency of MVD use in the different districts.

The number of MVDs performed for TGN per 100,000 population was approximately one-half of MVDs for hemifacial spasm. The morbidity rate for hemifacial spasm is 10.95/100,000 population, with the rate for TGN approximately one-half of that (4.3/100,000 population). It is conceivable that the difference in these morbidity rates is related to the difference in the number of operations.21,22)

Regarding outcomes at the time of discharge, the rate of “cure” was 5.8% and the rate of “improvement” was 91.8%. However, the definition of “cure” in the DPC database discharge status is that the patient does not need any further outpatient treatment, or he/she has been determined as being in the condition conforming thereto. In reality, however, for cases in which symptoms are cured but need to be followed up, or outpatient visits are necessary, the “improvement” status can be applied. On the basis of these definitions, it is conceivable that “improvement” was applied as the outcome to more patients with MVD having TGN at the time of their discharge. According to these considerations, cure and improvement were achieved in 97.6% of all cases, with a mortality rate of 0.2%. Compared with results reported in other studies, these outcomes appear to be favorable. However, because the DPC system lacks strict criteria for assessing outcomes at discharge for patients undergoing MVD (i.e., DPC data provide only discharge outcome), our results may not be directly comparable with those obtained in other studies.

Study limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the data not cover all participating DPC hospitals. The data were obtained only from DPC-participating hospitals contracted to the DPC Research Institute, not all medical institutions in Japan. In 2012, data were collected from 1222 of 1774 DPC-participating institutions, accounting for approximately 69% of all DPC data. Therefore, data from non-participating hospitals should be analyzed in the future to confirm the current status of MVD for the treatment of TGN in Japan. Second, due to limitations in the database (e.g., the DPC does not include data regarding treatment administered at outpatient clinics), DPC data are generally not useful for determining the incidence of complications in MVD, including auditory disorders, dysphagia, and facial paralysis. Therefore, analysis of data from a comprehensive, disease-specific registry would be preferable. Third, to protect personal information, the protocol of DPC studies does not permit investigation of cases of a disease numbering 10 or fewer. Therefore, details such as the cause and time of death were unclear. Finally, the DPC data did not provide information regarding long-term outcomes after MVD for the treatment of TGN because the DPC database houses in-hospital data only.

Conclusion

Analysis of data housed in the DPC database revealed discernable trends and patterns in the use of MVD for the treatment of TGN in Japan.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1).Cole CD, Liu JK, Apfelbaum RI: Historical perspectives on the diagnosis and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurg Focus 18: E4, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Eller JL, Raslan AM, Burchiel KJ: Trigeminal neuralgia: definition and classification. Neurosurg Focus 18: E3, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Eboli P, Stone JL, Aydin S, Slavin KV: Historical characterization of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery 64: 1183–1186; discussion 1186–1187, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Gronseth G, Cruccu G, Alksne J, et al. : Practice parameter: the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurological Societies. Neurology 71: 1183–1190, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Obermann M: Treatment options in trigeminal neuralgia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 3: 107–115, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Hitchon PW, Holland M, Noeller J, et al. : Options in treating trigeminal neuralgia: experience with 195 patients. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 149: 166–170, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Spatz AL, Zakrzewska JM, Kay EJ: Decision analysis of medical and surgical treatments for trigeminal neuralgia: how patient evaluations of benefits and risks affect the utility of treatment decisions. Pain 131: 302–310, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Kalkanis SN, Eskandar EN, Carter BS, Barker FG: Microvascular decompression surgery in the United States, 1996 to 2000: mortality rates, morbidity rates, and the effects of hospital and surgeon volumes. Neurosurgery 52: 1251–1261; discussion 1261–1262, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Tronnier VM, Rasche D, Hamer J, Kienle AL, Kunze S: Treatment of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: comparison of long-term outcome after radiofrequency rhizotomy and microvascular decompression. Neurosurgery 48: 1261–1267; discussion 1267–1268, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Ashkan K, Marsh H: Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in the elderly: a review of the safety and efficacy. Neurosurgery 55: 840–848; discussion 848–850, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Murata A, Okamoto K, Muramatsu K, Matsuda S: Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer: the influence of hospital volume on complications and length of stay. Surg Endosc 28: 1298–1306, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Murata A, Muramatsu K, Ichimiya Y, Kubo T, Fujino Y, Matsuda S: Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer in elderly Japanese patients: an observational study of financial costs of treatment based on a national administrative database. J Dig Dis 15: 62–70, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Murata A, Okamoto K, Muramatsu K, Kubo T, Fujino Y, Matsuda S: Effects of additional laparoscopic cholecystectomy on outcomes of laparoscopic gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer based on a national administrative database. J Surg Res 186: 157–163, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Murata A, Mayumi T, Muramatsu K, Ohtani M, Matsuda S: Effect of dementia on outcomes of elderly patients with hemorrhagic peptic ulcer disease based on a national administrative database. Aging Clin Exp Res 27: 717–725, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Wei Y, Pu C, Li N, Cai Y, Shang H, Zhao W: Long-term therapeutic effect of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia: Kaplan-Meier analysis in a consecutive series of 425 patients. Turk Neurosurg 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Zhang H, Lei D, You C, Mao BY, Wu B, Fang Y: The long-term outcome predictors of pure microvascular decompression for primary trigeminal neuralgia. World Neurosurg 79: 756–762, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Oesman C, Mooij JJ: Long-term follow-up of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Skull Base 21: 313–322, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Sindou M, Leston J, Decullier E, Chapuis F: Microvascular decompression for primary trigeminal neuralgia: long-term effectiveness and prognostic factors in a series of 362 consecutive patients with clear-cut neurovascular conflicts who underwent pure decompression. J Neurosurg 107: 1144–1153, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).McLaughlin MR, Jannetta PJ, Clyde BL, Subach BR, Comey CH, Resnick DK: Microvascular decompression of cranial nerves: lessons learned after 4400 operations. J Neurosurg 90: 1–8, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Katusic S, Beard CM, Bergstralh E, Kurland LT: Incidence and clinical features of trigeminal neuralgia, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945–1984. Ann Neurol 27: 89–95, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Mizobuchi Y, Muramatsu K, Ohtani M, et al. : The current status of microvascular decompression for the treatment of hemifacial spasm in Japan: an analysis of 2907 patients using the Japanese diagnosis procedure combination database. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 57: 184–190, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Auger RG, Whisnant JP: Hemifacial spasm in Rochester and Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1960 to 1984. Archiv Neurol 47: 1233–1234, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]