Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

Early introduction of cyclosporine did not improve HLH outcome in patients treated with the HLH-94 etoposide-dexamethasone backbone (P = .06).

HLH-2004 may be improved by risk-group stratification, less therapy reduction weeks 7 to 8 for verified FHL patients, and earlier HSCT.

Abstract

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome comprising familial/genetic HLH (FHL) and secondary HLH. In the HLH-94 study, with an estimated 5-year probability of survival (pSu) of 54% (95% confidence interval, 48%-60%), systemic therapy included etoposide, dexamethasone, and, from week 9, cyclosporine A (CSA). Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was indicated in patients with familial/genetic, relapsing, or severe/persistent disease. In HLH-2004, CSA was instead administered upfront, aiming to reduce pre-HSCT mortality and morbidity. From 2004 to 2011, 369 children aged <18 years fulfilled HLH-2004 inclusion criteria (5 of 8 diagnostic criteria, affected siblings, and/or molecular diagnosis in FHL-causative genes). At median follow-up of 5.2 years, 230 of 369 patients (62%) were alive (5-year pSu, 61%; 56%-67%). Five-year pSu in children with (n = 168) and without (n = 201) family history/genetically verified FHL was 59% (52%-67%) and 64% (57%-71%), respectively (familial occurrence [n = 47], 58% [45%-75%]). Comparing with historical data (HLH-94), using HLH-94 inclusion criteria, pre-HSCT mortality was nonsignificantly reduced from 27% to 19% (P = .064 adjusted for age and sex). Time from start of therapy to HSCT was shorter compared with HLH-94 (P = .020 adjusted for age and sex) and reported neurological alterations at HSCT were 22% in HLH-94 and 17% in HLH-2004 (using HLH-94 inclusion criteria). Five-year pSu post-HSCT overall was 66% (verified FHL, 70% [63%-78%]). Additional analyses provided specific suggestions on potential pre-HSCT treatment improvements. HLH-2004 confirms that a majority of patients may be rescued by the etoposide/dexamethasone combination but intensification with CSA upfront, adding corticosteroids to intrathecal therapy, and reduced time to HSCT did not improve outcome significantly.

Medscape Continuing Medical Education online

In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology. Medscape, LLC is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.00 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/blood; and (4) view/print certificate. For CME questions, see page 2811.

Disclosures

Editor Nancy Berliner received grants for clinical research from Novartis. CME questions author Laurie Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC, owns stock, stock options, or bonds from Alnylam, Biogen, and Pfizer Inc. Authors Maurizio Aricó and Jan-Inge Henter served as unpaid consultants for Novimmune. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

Assess survival in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) enrolled in the HLH-2004 therapeutic trial.

Identify neurologic complications and toxicity in patients with HLH enrolled in the HLH-2004 therapeutic trial.

Determine the clinical implications of long-term findings from the HLH-2004 therapeutic trial.

Release date: December 21, 2017; Expiration date: December 21, 2018

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a devastating disturbance of the immune system leading to an uncontrolled accumulation of macrophages and lymphocytes, and hyperinflammation. Without adequate therapy it is often fatal.1 Traditionally, HLH is divided into primary (inherited) and secondary (acquired) forms.2 Both can be diagnosed at any age.

The most common form of primary HLH is familial (familial/genetic HLH [FHL]). FHL is autosomal recessive, and mutations in 4 genes (PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and STXBP2) are today known to cause disease, all affecting the perforin pathway of lymphocyte cytotoxicity.3-6 Primary HLH also includes X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP), Griscelli syndrome type 2 (GS2), Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS), and Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (HPS). Secondary HLH (sHLH), more common in adults, is often associated with underlying conditions including severe infections, malignancies, or inflammatory disorders.2,7-9 Both primary HLH and sHLH are often triggered by infections.10

Clinical manifestations of HLH include prolonged fever, splenomegaly, cytopenias, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and hyperferritinemia. Hemophagocytosis is not required for diagnosis.11 The central nervous system (CNS) is commonly affected at onset, often leading to neurological late effects.1,12-16 It can be difficult to distinguish between primary HLH and sHLH at onset, and both often require chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy. For primary cases, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is required for cure,17-19 and may also be necessary for some forms of sHLH such as chronic active Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection.20,21

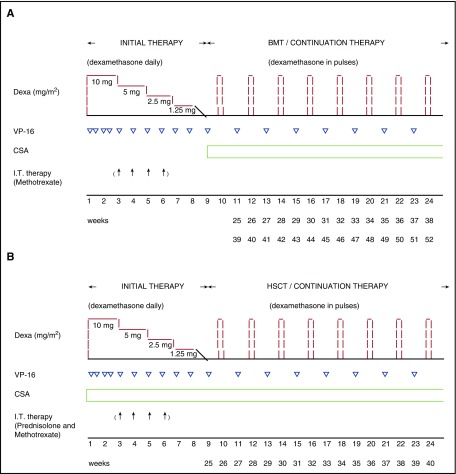

Three decades ago, long-term survival in HLH was <5%.1 Fortunately, thanks to collaborations worldwide and new treatment protocols including HSCT, many patients are now long-term survivors.12,22-26 In 1989, the Histiocyte Society established an HLH registry to which 122 patients were reported with a 5-year survival of 21%.27 In 1994, the Histiocyte Society launched the first international therapeutic study on HLH, HLH-94 (Figure 1A),12 with >200 eligible patients recruited worldwide. It resulted in a remarkably improved outcome with a 5-year probability of survival (pSu) of 54% ± 6%.15,24,26,28 Moreover, XLP, GS2, and CHS also responded well.29 However, early mortality and late neurological effects remained problematic: 29% died before HSCT and 19% displayed late neurological sequelae.15,24,26 A subsequent study, HLH-2004, was therefore initiated (Figure 1B). Here, we present a summary of HLH-2004 with focus on survival, mortality, toxicity, and comparisons with the historical control HLH-94.

Figure 1.

Overview of the treatment protocols. (A) HLH-94 and (B) HLH-2004. (A) Both HLH-94 and HLH-2004 consist of an initial therapy of 8 weeks, with immunosuppressive and cytotoxic agents, and continuation therapy thereafter, for patients with familial, relapsing, or severe and persistent, aiming at a HSCT as soon as an acceptable donor is available. In both HLH-94 and HLH-2004, daily dexamethasone (Dexa) (10 mg/m2 per day weeks 1-2; 5 mg/m2 per day weeks 3-4; 2.5 mg/m2 per day weeks 5-6; 1.25 mg/m2 per day week 7, and tapering during week 8), and etoposide (VP-16) (150 mg/m2, twice weekly weeks 1-2, then once weekly) is administrated during the initial therapy. The continuation therapy for both HLH-2004 and HLH-94 consists of Dexa every second week (10 mg/m2 per day for 3 days), VP-16 (150 mg/m2) every second week, and CSA (aiming at 200 µg/L trough value). For patients with progressive neurological symptoms during the first 2 weeks, or if an abnormal cerebrospinal fluid value at onset has not improved after 2 weeks, intrathecal (I.T.) treatment is recommended (up to 4 doses, weeks 3, 4, 5, 6). In the HLH-94 protocol, I.T. MTX (doses by age: <1 year, 6 mg; 1-2 years, 8 mg; 2-3 years, 10 mg; >3 years, 12 mg each dose) is recommended. (B) In HLH-2004, CSA (aiming at 200 µg/L trough value) is administered already upfront during the initial therapy, a modification from HLH-94 where CSA is not administered until the continuation therapy. It is recommended to start CSA with 6 mg/kg daily orally (divide in 2 daily doses), if normal kidney function. Moreover, in the HLH-2004 protocol, in addition to I.T. MTX, I.T. prednisolone (doses by age: <1 year, 4 mg; 1-2 years, 6 mg; 2-3 years, 8 mg; >3 years, 10 mg each dose) is recommended. In HLH-2004, the total treatment period is reduced to 40 weeks as compared with 52 weeks in HLH-94. Reprinted from Henter et al12 (A) and Henter et al11 (B) with permission. BMT, bone marrow transplantation.

Treatment protocol, patients, and methods

The HLH-2004 treatment protocol

HLH-2004 was based on HLH-94, with 8 weeks of initial treatment followed by a continuation phase, both including etoposide and dexamethasone (Figure 1). The first and main aim was “to provide and evaluate a revised initial and continuation therapy, with the goal to initiate and maintain an acceptable condition in order to perform a curative SCT, for patients with familial, relapsing, or severe and persistent HLH.”11 As compared with HLH-94, 3 treatment changes were made. (1) Due to high mortality weeks 1 to 8, treatment was intensified by administrating cyclosporine A (CSA) upfront, aimed at increasing immunosuppression without inducing additional myelotoxicity. Notably, CSA had been reported to inhibit production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ),30 and to be beneficial in initial HLH treatment.31 (2) To reduce time to HSCT, it was recommended that HSCT be performed as soon as an acceptable donor was available. (3) Given their beneficial systemic effect, corticosteroids were added to the intrathecal (IT) methotrexate (MTX) treatment recommended for a subset of patients. For nonverified FHL patients with complete disease resolution after 8 weeks, it was recommended that treatment was stopped.

The choice of HSCT donor, timing, conditioning regimen, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis were determined by the treating physician. A suggested conditioning regimen was, however, provided, including busulfan, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, with CSA and methotrexate (or mycophenolate) as GVHD prophylaxis. When using an unrelated donor, antithymocyte globulin (ATG) was also recommended. When the study was initiated in 2004, limited data were available on reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC), hence no firm suggestions on RIC were provided.32

Study-specific clinical report forms were completed by the treating hospitals at start of treatment and after 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 2 months, 6 months, and thereafter annually. For transplanted patients, data were reported at transplantation, 100 days post-HSCT, and then annually. Serious adverse events (SAEs) and mortality reports were sent to the principal investigator, and subsequently to the external data safety monitoring board. The study started 1 January 2004, and closed for enrollment on 31 December 2011. Cutoff for data entry was 31 March 2016.

The HLH-2004 study was approved by the Histiocyte Society, and the Karolinska Institute Ethics Committee, and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (identifier, NCT00426101).

Patients

In HLH-94, 5 of 5 criteria (fever, splenomegaly, bicytopenia [hemoglobin (Hb), <90 g/L; platelets, <100 × 109/L; absolute neutrophil count (ANC), <1.0 × 109/L], hypertriglyceridemia [fasting triglycerides, ≥2.0 mmol/L], and/or hypofibrinogenemia [fibrinogen, ≤1.5 g/L], and hemophagocytosis), and/or an affected sibling (ie, “familial patients”) were required.12 In HLH-2004, 3 new diagnostic criteria were implemented: ferritin ≥ 500 µg/L, low/absent (<10 lytic units) natural killer (NK)-cell activity, and soluble CD25 (soluble interleukin-2 receptor [sIL-2r]) (≥2400 U/mL).11 HLH-2004 enrollment required: 5 of 8 diagnostic criteria, an affected sibling, and/or a molecular diagnosis in FHL-causative genes (PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, STXBP2). Inclusion age was increased from <16 to <18 years.11,12 Inclusion criteria were: no prior cytotoxic or CSA treatment, no other underlying disease, an intention to treat according to HLH-2004, and reported follow-up. Modifications of dosages were allowed, as long as all medications were administered. Supportive therapy or anti-infectious agents, including rituximab for EBV infection (n = 14), was accepted.

Altogether, 369 patients (all with active HLH) from 27 countries were eligible (Argentina, Austria, Bahrain, Belarus, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, The Netherlands, Norway, Oman, Portugal, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and United States of America). For the HLH-94 criteria and ferritin, information was available in 347 to 351 of 369 (94%-95%), whereas information on NK-cell activity and sIL-2r was available for 240 (65%) and 223 (60%), respectively (Table 1). Hemophagocytosis was found in 287 of 349 (82%) with information available, and in other organs than bone marrow in only 15 of 287 (most commonly the spleen, n = 8). In addition, information on aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase values were available in 319 of 369 (86%) and 333 of 369 (90%), respectively, of which 243 of 319 (76%) and 186 of 333 (56%) were >120 U/L.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria fulfilled by the 369 eligible patients in HLH-2004

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes* | No* | Missing/not done* | |

| Fever | 335 (95) | 16 (5) | 18 (5) |

| Splenomegaly | 314 (89) | 37 (11) | 18 (5) |

| Bicytopenia (≥2/3 cell lineages)† | 323 (92) | 28 (8) | 18 (5) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia or Hypofibrinogenemia‡ | 314 (90) | 33 (10) | 22 (6) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia‡ | 221 (65) | 118 (35) | 30 (8) |

| Hypofibrinogenemia‡ | 257 (75) | 84 (25) | 28 (8) |

| Hemophagocytosis | 287 (82) | 62 (18) | 20 (5) |

| Ferritin§ | 327 (94) | 21 (6) | 21 (6) |

| Low/absent NK-cell activity|| | 171 (71) | 69 (29) | 129 (35) |

| Soluble CD25 (sIL-2r)¶ | 216 (97) | 7 (3) | 146 (40) |

Displayed are patients (n) who fulfilled each criterion. For the yes/no columns, the percentage is given without including patients with missing data or for whom the analysis was not done. For the missing/not done columns, the percentage is given for the whole population.

Hb, <90 g/L; platelets, <100 × 109/L; ANC, <1.0 × 109/L.

Fasting triglycerides, ≥3.0 mmol/L (265 mg/dL), fibrinogen, ≤1.5 g/L.

Ferritin, ≥500 µg/L.

Low/absent (<10 lytic units) NK-cell activity.

Soluble CD25 (sIL-2r), ≥2400 U/mL.

The patients (n = 369) were evaluated not only as 1 single cohort but also as subgroups: patients with verified FHL-causative mutations or an affected sibling (n = 168), and patients without any of these 2 characteristics (n = 201). Separately, to compare the HLH-2004 and HLH-94 protocols, HLH-2004 patients were also divided into 2 “criteria subgroups,” 1 where HLH-94 criteria were fulfilled (n = 240) and 1 where HLH-2004 criteria were fulfilled but not HLH-94 criteria (n = 129).

Furthermore, as stated in the protocol, patients with XLP, GS2, CHS, and HPS (n = 29) were analyzed separately.11 Patients with other known underlying defined diseases or immunodeficiencies, that is, malignancies, systemic rheumatic diseases, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Kawasaki disease, or Leishmaniasis, were excluded from the present analyses.

Statistical analyses

The Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables, and Fisher exact and χ2 tests for categorical variables. pSu was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method for univariate tests, and the Cox proportional hazards model for multivariate tests. Competing risk methodology was used when analyzing time to HSCT and death prior to HSCT.33 Confounders (age and sex) were adjusted for. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated and P values <.05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS (version 23; IBM SPSS for Windows, IBM Corp, Chicago, IL) or R (version 3.2.3; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

General characteristics and outcome

Altogether, 369 patients were eligible. This makes HLH-2004 the largest prospective study on HLH to date. From the first HLH registry in 1989 to the 2 therapeutic studies HLH-94 and HLH-2004, >700 patients have been evaluated,26,27 a remarkable amount for such a rare disorder.

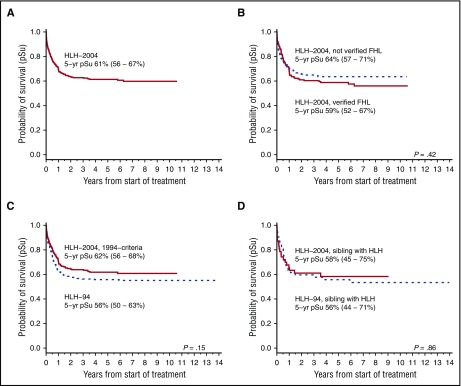

In HLH-2004, 230 of 369 patients (62%; median follow-up, 5.2 years) were alive at last follow-up with an estimated 5-year pSu of 61% (56%-67%) (Figure 2A). One aim with HLH-2004 was to induce resolution so that HSCT could be performed, and 187 patients (51%) were reported to have achieved resolution at 2 months (20 of whom had had a reactivation). An overview of the outcome in HLH-2004 and HLH-94 is presented in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Overall survival in HLH-2004. pSu for all patients and for different subgroups in the HLH-2004 study. The 5-year pSu is displayed with a 95% CI. (A) Five-year pSu for the entire HLH-2004 cohort (n = 369). (B) Five-year pSu for patients with an affected sibling or genetically verified FHL in HLH-2004 (n = 168) and for patients without verified FHL (n = 201) (dashed line); (P = .42, log rank). (C) Five-year-pSu for patients in HLH-2004 that fulfilled the HLH-94 inclusion criteria (n = 240) compared with patients in HLH-94 (n = 232) (dashed line); (P = .15, log rank). (D) Five-year pSu for familial patients (affected sibling) in HLH-2004 (n = 47) compared with familial patients (affected sibling) in HLH-94 (n = 52) (dashed line); (P = .86, log rank).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and outcome for the entire HLH-2004 cohort, for subgroups of the HLH-2004 cohort, and, for comparison, data from the study HLH-94

| HLH-2004 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 369 | Verified FHL,* n = 168 | Not verified FHL,* n = 201 | HLH-94 criteria,† n = 240 | HLH-2004 criteria only,‡ n = 129 | HLH-94 n = 232 | |

| General information | ||||||

| Median age at onset, mo | 12.6 | 3.4 | 21.4 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 8.3 |

| Male sex (%) | 187 (51) | 77 (46) | 110 (55) | 118 (49) | 69 (53) | 123 (53) |

| Consanguinity (%) | 58 (16) | 50 (30) | 8 (4) | 39 (17) | 19 (16) | 43 (19) |

| Verified FHL* | 168 (46) | 168 (100) | N.A. | 121 (50) | 47 (36) | 52 (22) |

| Affected sibling (% of all) | 47 (13) | 47 (28) | N.A. | 47 (20) | N.A.§ | 52 (22) |

| Biallelic FHL mutations (% of all) | 158 (43) | 158 (94) | N.A. | 111 (46) | 47 (36) | N.A. |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Dead, no HSCT (% of all) | 75 (20) | 28 (17) | 47 (23) | 46 (19) | 29 (22) | 63 (27) |

| Dead at 2 mo (% of all) | 50 (14) | 19 (11) | 31 (15) | 27 (11) | 23 (18) | 33 (14) |

| Dead at 6 mo (% of all) | 63 (17) | 22 (13) | 41 (20) | 37 (15) | 26 (20) | 46 (20) |

| Dead at 1 y (% of all) | 67 (18) | 23 (14) | 44 (22) | 41 (17) | 27 (21) | 56 (24) |

| HSCT performed (%) | 185 (50)|| | 133 (79)|| | 52 (26)|| | 133 (55)|| | 52 (40)|| | 118 (51) |

| Median time to HSCT, d | 148 | 129 | 192 | 154 | 147 | 180 |

| Alive post-HSCT (% of HSCT) | 121 (65) | 93 (70) | 29 (56) | 90 (68) | 31(60) | 78 (66)¶ |

| Dead post-HSCT (% of HSCT) | 64 (35) | 40 (30) | 23 (44) | 43 (32) | 21(40) | 40 (34) |

| Off therapy >1 y, alive without HSCT (%) | 88 (24)# | 2** (1) | 86 (43) | 48 (20) | 37 (29) | 48 (21) |

| Survival | ||||||

| 5-y pSu (95% CI) | 61 (56-67) | 59 (52-67) | 64 (57-71) | 62 (56-68) | 61 (53-70) | 56 (50-63) |

| 5-y pSu post-HSCT (95% CI) | 66 (59-73) | 70 (63-78) | 54 (40-68) | 67 (60-76) | 61 (48-74) | 66 (58-75) |

N.A., not applicable.

FHL was defined as having either biallelic mutations in FHL-causative genes (PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and STXBP2) or an affected sibling, whereas in HLH-94 familial (primary) HLH was defined as having an affected sibling.

Patients within the HLH-2004 study who fulfilled the HLH-94 criteria (5 of 5).

Patients within the HLH-2004 who only fulfilled the HLH-2004 criteria (5 of 8) but not the HLH-94 criteria (5 of 5).

By definition, if a patient had an affected sibling, the patient fulfilled the HLH-94 criteria.

Altogether, 3 additional patients were reported as having received a HSCT but further information on the HSCT was missing; 2 with and 1 without verified FHL; regarding fulfilled criteria, 1 patient fulfilled the HLH-2004 criteria and 2 fulfilled the HLH-94 criteria.

Includes 1 patient who also developed acute myelogenous leukemia, received a transplantation and survived.

In addition, 18 patients were reported as alive without HSCT with <1 y follow-up, 5 of these were reported as lost to follow-up.

These 2 patients, both alive for ≥5 y after onset of therapy, displayed biallelic PRF1 p.Ala91Val mutations, sometimes considered polymorphisms.34

Primary HLH and sHLH

Altogether, 295 patients (80%) were evaluated for FHL-causative genes; 67 were not studied (missing data = 7). Many analyses were made retrospectively, sometimes postmortem. Of these 295, 158 displayed biallelic FHL-causative mutations whereas 137 did not (90 were screened for ≥3 FHL genes, 43 for 1-2 FHL genes, and 4 had monoallelic mutations reported).

One hundred sixty-eight patients (46%) were either familial cases or displayed biallelic gene defects in PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, or STXBP2, that is, had verified FHL, with an overall 5-year pSu of 59% (52%-67%), as compared with 64% (57%-71%) in patients without verified FHL (n = 201) (Figure 2B). One hundred fifty-eight of 168 patients were identified with biallelic FHL-causative mutations (5-year pSu, 61% [53%-69%]). Fifty-nine of 158 displayed PRF1 mutations (5-year pSu, 55% [43%-69%]), 73 of 158 UNC13D mutations (5-year pSu, 64% [53%-76%]), 6 of 158 STX11 mutations (5-year pSu, 63% [21%-105%]), and 20 of 158 STXBP2 mutations (5-year pSu, 64% [45%-89%]). Forty-seven patients had an affected sibling (5-year pSu, 58% [45%-75%]) (Figure 2D), of whom 37 (79%) had biallelic FHL-causative mutations identified.

Additionally, patients with mutations in other HLH-associated genes were studied separately. These 29 patients (XLP [n = 16], GS2 [n = 11], CHS [n = 1], HPS [n = 1]) had a 5-year pSu of 59% (43%-81%).

Infections at diagnosis

One hundred thirty-seven patients (37%) had a reported infection at diagnosis; 32 of these (23%) were patients with verified FHL. Of these, 93 either had EBV (n = 74), cytomegalovirus (CMV) (n = 14), or combined EBV/CMV (n = 5) infection at onset (DNA copies were often not reported). Sixteen of 93 EBV/CMV-infected patients had verified FHL (EBV = 6, CMV = 8, combined EBV/CMV = 2). Seventeen of 74 EBV-infected patients (23%; 5 with verified FHL) underwent HSCT with 9 HSCT survivors, whereas 11 of 74 died without a HSCT (none with verified FHL) and 46 of 74 (62%) were alive without a HSCT.

Mortality in patients not receiving HSCT

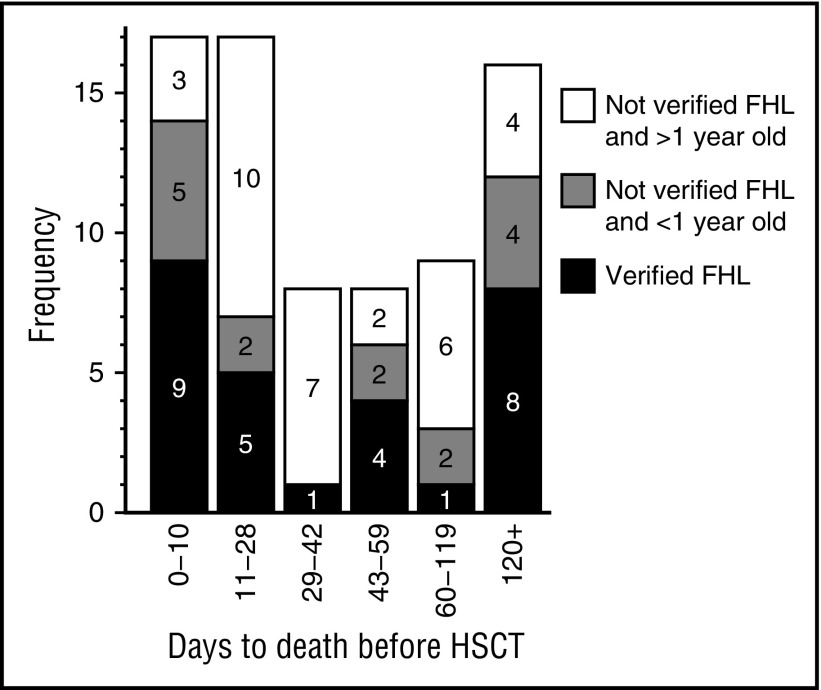

In order to identify therapeutically meaningful information, pre-HSCT fatalities during different treatment-related time periods were thoroughly analyzed. Seventy-five of 369 patients (20%) died without HSCT; 50 within the first 2 months of treatment (17 during the first 10 days, 17 during days 11-28, and 16 during days 29-59; median age at onset, 4, 30, and 13 months, respectively). Another 9 died days 60 to 119 (median age, 17 months) and 16 thereafter (8 >365 days after onset; median age at onset, 17 months). Notably, only 28 of 75 (37%) who died pre-HSCT had verified FHL (verified biallelic mutations = 23, affected sibling = 5).

The 17 patients who died days 11 to 28 had remarkably high median age at onset and, notably, 10 of 17 (59%) were aged ≥1 year and without verified FHL as opposed to 3 of 17 (18%) who died during the first 10 days (P = .032) (Figure 3). Among these 10 patients, septicemia, infections, and/or bleedings (associated with thrombocytopenia) were diagnoses reported by the treating physicians in 7 patients; possibly associated with treatment toxicity. Analyzing the treatment period up to 6 weeks, this pattern was further strengthened because 17 of 25 (68%) who died days 11 to 42 were aged ≥1 year and without verified FHL as compared with 3 of 17 who died during the first 10 days (P = .018) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Analyses of patients who died without HSCT with regard to time of death after onset of therapy and type of patient. All patients who died without having a HSCT (n = 75) were divided into 3 groups; (a) verified FHL (verified biallelic mutations = 23, affected sibling = 5), (b) without verified FHL and ≥1-year old at onset (n = 32), and (c) without verified FHL and <1 year old at onset (n = 15). Notably, 10 of 17 (59%) who died days 11 to 28 were aged ≥1 year and without verified FHL as opposed to 3 of 17 (18%) who died the first 10 days (P = .032), and of these 10 patients, 7 had findings possibly associated with toxicity related to overtreatment. Analyzing the treatment period days 11 to 42, this pattern was further strengthened (P = .018). In contrast, among the 8 (4 with verified FHL) who died days 43 to 60, 6 (75%) were reported to suffer active HLH, possibly suggesting a need of less reduction of initial treatment during this period. Finally, 8 of 16 (50%) who died after day 120 had verified FHL, many of whom died of disease reactivation, stressing the importance of an early HSCT for this cohort.

In contrast, among the 8 (4 with verified FHL) who died days 43 to 59, 6 (75%) were reported by the treating physicians to suffer “refractory HLH,” “fulminant HLH,” “active HLH,” “multiorgan failure,” “progressive disease,” and “HLH reactivation.”

The information in this section suggests that treatment possibly should be (1) risk group stratified and (2) less aggressive days 11 to 42 for some patients, and (3) with less reduction of initial treatment days 43 to 59 for verified FHL patients.

Finally, there was an overrepresentation of deaths after the first 100 days in patients who had had resolution and reactivation, and 8 of 16 children who died after day 120 had verified FHL, stressing the importance of acute/subacute HSCT for these patients (Figure 3).

Serious adverse events

No suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction was reported. In total, 89 SAEs grade III or IV were reported, of which 48 reported 1 or more suspected causative drugs. With regard to 1 single suspected drug, 13 reported CSA (the most common complication being CNS affection, n = 6), 6 reported etoposide (the hepatobiliary system being most frequently affected, n = 3), and 6 reported dexamethasone (5 with cardiac hypertension). In 15 reports, 2 drugs were suspected (CSA = 14, dexamethasone = 14, etoposide = 2), with the most common SAE being cardiac hypertension associated with dexamethasone and CSA (n = 11). Eight reports suspected all 3 drugs to be involved, with infections (n = 5) being most frequent. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) was altogether mentioned in 3 SAE reports (2 were drug-associated, both with CSA).

In addition, as in HLH-94,26 1 patient developed acute myeloid leukemia (AML). This patient received no etoposide after 3 weeks of therapy due to infections, and was in complete resolution at 2 months. Two years later, the patient was diagnosed with AML and underwent HSCT but died.

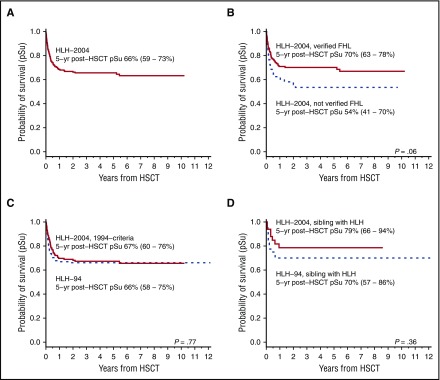

HSCT outcome

One hundred eighty-eight of 369 patients (51%) in HLH-2004 underwent HSCT. Of these, data were available for 185 of whom 121 (65%) were alive at last follow-up (5-year pSu post-HSCT, 66% [59%-73%]) (Figure 4A). One hundred thirty-five of 188 (72%) had verified FHL with 5-year pSu of 70% (63%-78%) (no data = 2) as compared with 54% (63%-78%) for patients without verified FHL (n = 52) (P = .06, log rank) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Survival after HSCT. Survival data after HSCT (n = 185). The 5-year pSu is displayed with a 95% CI. (A) Five-year pSu after HSCT for the entire HLH-2004 cohort (n = 185). (B) Five-year pSu for patients with an affected sibling or genetically verified FHL in HLH-2004 (n = 133) and for patients without verified FHL (n = 52) (dashed line); (P = .06, log rank). (C) Five-year pSu after HSCT for patients in HLH-2004 who fulfilled the HLH-94 inclusion criteria (n = 133), compared with patients in HLH-94 (n = 118) (dashed line); (P = .77, log rank). (D) Five-year pSu after HSCT for familial patients (affected sibling) in HLH-2004 (n = 33) compared with familial patients (affected sibling) in HLH-94 (n = 40) (dashed line); (P = .36, log rank).

Fifteen (8%) were transplanted before 2 months of therapy, 60 (32%) between 2 and 4 months. Six months after starting treatment, 118 (64%) had received HSCT. The median time to HSCT was 148 days (range, 25-2105 days).

Sixty-four patients died post-HSCT, 36 (56%) prior to day +100, 57 (89%) within the first year, and 7 thereafter. According to reporting clinicians, 31 deaths (48%) were reported as transplant-related mortality (TRM), 16 (25%) as dead of disease/relapse/graft failure, in 11 (17%) the cause of death could not be specified as TRM or death of disease, and 1 (2%) died of a surgical complication. Mortality data were missing in 5 cases.

Patients alive without HSCT

Both HLH-2004 and HLH-94 were designed so that patients without FHL, relapsing, or severe and persistent HLH should stop treatment after 2 months. In HLH-2004, 88 of 369 patients (24%; median age at onset, 2.3 years; range, 33-5675 days) stopped therapy and were off HLH treatment of >1 year and alive without HSCT, that is, presumed sHLH. Interestingly, 2 of these 88 patients, both alive for ≥5 years, displayed biallelic PRF1 p.Ala91Val mutations, a variant debated but sometimes considered a polymorphism.34 Notably, 6 patients had reactivated after stopping initial therapy and restarted initial therapy before they finally became off treatment, but despite their reactivations these 6 were all alive without HSCT. Another patient was off HLH treatment ≥1 year but died due to other reasons (congenital heart failure). In addition, 18 were alive without HSCT with <1 year follow-up.

Comparisons between HLH-2004 and HLH-94

When comparing HLH-2004 with the historical control HLH-94 (n = 232), HLH-2004 patients were divided into 2 groups. In 1 group, patients fulfilled all 5 HLH-94 criteria (n = 240) (“HLH-2004, 1994-criteria”) and in the other 5 of 8 HLH-2004 criteria but not the HLH-94 criteria (n = 129) (“HLH-2004, 2004-criteria”). Patients who fulfilled the HLH-94 criteria in both studies were compared.12 Baseline characteristics were comparable between the 2 studies (Table 2). Patients with an affected sibling (HLH-2004 [n = 47] and HLH-94 [n = 52]) also underwent special evaluation.11,26

Treatment intensification.

For the HLH-2004, 1994-criteria subgroup, 151 (63%) were alive at last follow-up. This subgroup had a nonsignificant tendency to better survival (5-year pSu, 62% [56%-68%]) compared with HLH-94 (5-year pSu, 56% [50%-63%]) with an HLH-94 vs HLH-2004 hazard ratio (HR) of death of 1.23 (95% CI, 0.93-1.64; P = .15) (Figure 2C). Patients included in the HLH-2004, 2004-criteria subgroup displayed a 61% 5-year pSu (53%-70%). Five-year pSu for familial patients in HLH-2004 was 58% (45%-75%) and 56% (44%-71%) in HLH-94 (Figure 2D).

In the HLH-2004, 1994-criteria subgroup, 46 (19%) died pre-HSCT compared with 63 (27%) in HLH-94. Pre-HSCT mortality was further compared using the competing risk methodology, with death and HSCT considered competing events.33 The HLH-94 vs the HLH-2004, 1994-criteria subgroup displayed a HR of 1.45 (0.99-2.12; P = .055), approaching borderline statistical significance to enhanced pre-HSCT survival in HLH-2004. Adjusted for age and sex, the HR was 1.44 (0.98-2.11; P = .064). Among familial patients in HLH-2004, 12 of 47 (26%) died before HSCT, as compared with 12 of 52 (23%) in HLH-94.

In the HLH-2004, 1994-criteria subgroup, 48 of 240 (20%) were off treatment of >1 year and alive without HSCT (median age at onset, 2.5 years), results similar to HLH-94 (48 of 232, 21%) (median age, 2.4 years). Median age at start of therapy, as well as the proportion of patients alive without HSCT, that is, presumed sHLH, were therefore similar in the 2 studies.

During the first 2 months, when CSA was administered in HLH-2004 using the same inclusion criteria, reactivations (15 of 240, 6%) and mortality (27 of 240, 11%) in HLH-2004 were comparable to HLH-94, 18 of 232 (8%), and 33 of 232 (14%), respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Detailed information on treatment and outcome for the entire HLH-2004 cohort, for subgroups of the HLH-2004 cohort, and for comparison data from HLH-94 study

| HLH-2004 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 369 | Verified FHL,* n = 168 | Not verified FHL, n = 201 | HLH-94 criteria,† n = 240 | HLH-2004 criteria only,‡ n = 129 | HLH-94 n = 232 | |

| Clinical status at 2 mo | ||||||

| Dead at 2 mo (% of all) | 50 (14) | 19 (11) | 31 (15) | 27 (11) | 23 (18) | 33 (14) |

| HSCT during the first 2 mo (% of all) | 15 (4) | 12 (7) | 3 (1) | 12 (5) | 3 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Achieved a resolution, had reactivation (% of all)§ | 19 (5) | 8 (5) | 11 (5) | 15 (6) | 4 (3) | 18 (8) |

| Treatment according to protocol|| | ||||||

| Etoposide according to plan weeks 1-2 | ||||||

| Yes | 254 (83) | 114 (84) | 140 (81) | 166 (81) | 88 (85) | 176 (86) |

| No | 53 (17) | 21 (16) | 32 (19) | 38 (19) | 15 (15) | 29 (14) |

| Missing | 62 (17) | 33 (20) | 29 (14) | 36 (15) | 26 (20) | 27 (12) |

| Etoposide according to plan weeks 3-8 | ||||||

| Yes | 214 (72) | 93 (73) | 121 (72) | 140 (70) | 74 (78) | 148 (74) |

| No | 82 (28) | 35 (27) | 47 (28) | 61(30) | 21 (22) | 52 (26) |

| Missing | 73 (20) | 40 (24) | 33 (16) | 39 (16) | 34 (26) | 32 (14) |

| Dexamethasone according to plan weeks 1-8 | ||||||

| Yes | 254 (83) | 109 (81) | 145 (85) | 163 (80) | 91 (89) | 171 (85) |

| No | 52 (17) | 26 (19) | 26 (15) | 41 (20) | 11 (11) | 31 (15) |

| Missing | 63 (17) | 33 (20) | 30 (15) | 36 (15) | 27 (21) | 30 (13) |

| CSA according to plan weeks 1-8 | ||||||

| Yes | 261 (85) | 114 (84) | 147 (85) | 170 (83) | 91 (88) | N.A. |

| No | 46 (15) | 21 (16) | 25 (15) | 34 (17) | 12 (12) | N.A. |

| Missing | 62 (17) | 33 (20) | 29 (14) | 36 (15) | 26 (20) | N.A. |

| IT therapy administrated 0-2 mo | ||||||

| Yes | 71 (24) | 52 (39) | 19 (12) | 57 (29) | 14 (14) | 58 (28) |

| No | 227 (76) | 81 (61) | 146 (88) | 141 (71) | 86 (86) | 147 (72) |

| Missing | 71 (19) | 35 (21) | 36 (18) | 42 (18) | 29 (22) | 27 (12) |

In HLH-2004, verified FHL was defined as having either biallelic mutations in FHL-causative genes (PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and STXBP2) or an affected sibling.

Patients within the HLH-2004 study who fulfilled the HLH-94 criteria (5 of 5).

Patients within the HLH-2004 who only fulfilled the HLH-2004 criteria (5 of 8) but not the HLH-94 criteria (5 of 5).

As reported by the treating physicians.

For the yes/no columns, the percentage is given without including patients with missing data or not applicable patients. For the missing/not applicable columns, the percentage is given for the whole population. Regarding “Etoposide according to plan weeks 3-8,” missing data includes the not applicable data on patients who died weeks 1 to 2.

Results related to HSCT.

For the HLH-2004, 1994-criteria subgroup, median time to HSCT was 154 days (range, 25-2105 days) whereas in HLH-94 it was 180 days (range, 42-1189 days) (HR = 1.25 [0.99-1.6]; P = .074). Adjusted for age and sex, HR was 1.34 (1.047-1.71; P = .020), that is, time to HSCT was significantly reduced in HLH-2004. Among familial patients, median time to HSCT was 126 days (range, 27-2105 days) in HLH-2004 and 165 days (range, 50-1189 days) in HLH-94 (HR = 1.09; 0.69-1.73; P = .70).

In the HLH-2004, 1994-criteria subgroup, 135 (56%) were transplanted with a 5-year pSu post-HSCT of 67% (60%-76%) (no data = 2). In HLH-94, 5-year pSu post-HSCT was 66% (58%-75%) (Figure 4C). For familial patients in HLH-2004, 5-year pSu post-HSCT was 79% (66%-94%) as compared with 70% (57%-86%) in HLH-94 (Figure 4D).

Neurological alterations.

In HLH-2004, 32% displayed CNS involvement at diagnosis, and 17% had CNS complications after 2 months of therapy. For the HLH-2004, 1994-criteria subgroup, 81 of 240 (34%) had neurological alterations at start of therapy, 37 of 205 (18%) displayed CNS complications at 2 months, and 22 of 133 (17%) at start of conditioning. In HLH-94, the corresponding numbers were 32% at onset, 13% at 2 months, and 22% at HSCT (P = .62, P = .22, and P = .26, respectively), that is, the outcome of neurological alterations was not significantly different between the studies.

Discussion

HLH-2004, the second international HLH-study launched by the Histiocyte Society, recruited 369 eligible patients and is, to our knowledge, the largest prospective therapeutic study on HLH to date. Combined with HLH-94 and the first international registry from the Histiocyte Society, over 700 patients have been evaluated, of whom over 600 were prospectively recruited.11,26,27 This is outstanding for such a rare disorder, making the Histiocyte Society an example of what researchers and physicians can accomplish for patients through worldwide collaboration. HLH-2004 itself displays the same international collaborative success with 27 participating countries.

Long-term survival in HLH has improved dramatically over the last decades, from a few percent in the early 1980s, with 1 long-term survivor with verified familial HLH first treated in 1981 still alive,1,27,35,36 to an overall 5-year pSu of 54% in HLH-94, and a 5-year pSu of 61% in HLH-2004.24,26 The reduced pre-HSCT mortality from 27% in HLH-94% to 19% in HLH-2004 was rewarding. Furthermore, both FHL patients (with biallelic mutations in PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, STXBP2, or an affected sibling) and patients with related disorders (XLP, GS2, CHS, and HPS) displayed an overall 5-year pSu of 59%, confirming that the treatment is valuable for patients with all of these genetic defects.29

During the first 2 months of treatment, there was no significant reduction in mortality and reactivations in HLH-2004 as compared with HLH-94. However, there was a trend to reduced pre-HSCT mortality (P = .064 adjusted for age and sex), statistically analyzed using competing risk methodology.33 However, a weakness of HLH-2004 was the nonrandomized design, hence the historical control HLH-94 was used, which obviously makes conclusions less reliable, in particular because supportive care, including anti-infectious treatment, has in all likelihood improved over time.

Altogether, 121 of 185 patients (65%) who underwent HSCT were alive at last follow-up and the overall 5-year pSu post-HSCT was 66%, unfortunately not better than in HLH-94 (Figure 4C). However, time to HSCT (median, 154 days) was significantly reduced in HLH-2004 compared with HLH-94 (P = .020, adjusted for age and sex).

CNS involvement including encephalopathy is frequent in HLH and may result in potentially severe late neurological effects.15,16 In HLH-2004, IT corticosteroids were added to the IT MTX suggested in HLH-94 and, in addition, CSA was initiated on day 1; both were alterations that hopefully would reduce late neurological effects. In HLH-2004, 32% displayed neurological alterations at diagnosis, 17% after 2 months, and 19% at start of HSCT conditioning; proportions not significantly different from those in HLH-94. Notably, despite the increased focus on CNS symptoms in HLH-2004, the proportion of children with reported neurological alterations at HSCT was 22% in HLH-94 and 17% in HLH-2004 (using the HLH-94 inclusion criteria). It has been suggested that CSA may contribute to PRES in HLH,37,38 but PRES has also been associated with other drugs, including corticosteroids.39,40 Notably, encephalopathy is common in the natural course of HLH, and CSA has been reported to be beneficial in rheuma-associated HLH/macrophage activation syndrome.41 In our data, we found no evidence of a marked increase of CSA-induced PRES.

Corticosteroids are important anti-inflammatory drugs for HLH, with dexamethasone having higher concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid and a longer half-life in the CNS than prednisone.42 Importantly, etoposide can compensate for the cytotoxic defect in FHL and, more specifically, if lymphocytes isolated from FHL patients were subjected to etoposide in vitro, this normalized the otherwise deficient induction of apoptosis.43 Moreover, etoposide can substantially alleviate all symptoms of murine HLH, and the therapeutic mechanism of etoposide involves potent selective deletion of activated T cells and efficient suppression of inflammatory cytokine production.44 Etoposide may induce secondary AML,45 but only 2 of over 600 eligible patients included in the HLH-94/HLH-2004 studies were reported to develop malignancies, hence we feel secure in recommending treatment with etoposide for future HLH studies.

Importantly, based on reports by treating physicians, treatment with HLH-94/HLH-2004 may, possibly, be further improved (Figure 3). (1) Only 28 of 75 (37%) of the patients who died pre-HSCT had verified FHL, whereas in 47 of 75, a verified genetic defect was not identified or not analyzed and, notably, 32 of these 47 (68%) were ≥1 year at onset of disease. Deaths in these somewhat older patients without verified FHL were significantly overrepresented during days 11 to 28, and many of these deaths may be associated with toxicity, suggesting that reduced early cytotoxic therapy might be beneficial for these patients (such as etoposide once weekly instead of twice).46 (2) In contrast, many who died days 43 to 59 suffered active HLH, possibly suggesting a value of intensified therapy during this phase for verified FHL patients compared with the reduced treatment intensity in HLH-2004. (3) Finally, 8 of 16 (50%) who died >120 days after start of initial treatment had verified FHL. Many of these died of reactivation of disease, stressing the importance of an early HSCT.

The results of HLH-2004 compare well with the largest study reported on ATG-based therapy with an overall survival of 21 of 38 (55%) obtained in a highly experienced center.25 Nevertheless, despite the reduced pre-HSCT mortality in HLH-2004 from 27% to 19%, there is still a need for improved pre-HSCT survival; interesting trials with alternative therapeutic approaches for HLH have been initiated, including ATG in combination with etoposide (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01104025), alemtuzumab (NCT02472054),47 tocilizumab (NCT02007239),48,49 ruxolitinib (NCT02400463),50,51 and a targeted anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (NCT01818492).52-55 Whether these drugs can be sufficient to halt HLH alone or require the addition of etoposide remains to be elucidated, as well as how they are best used (doses, drug combinations, in adults/children, etc).

We conclude that the improvement in survival in HLH/FHL has been extraordinary over the past decades but that the reduced pre-HSCT mortality in HLH-2004 by around one-third, from 27% to 19% compared with HLH-94, was not sufficient to reach statistical significance (P = .064). Positively, time to HSCT was significantly reduced (P = .020), but not neurological alterations. There is thus no strong statistical evidence to suggest HLH-2004 instead of HLH-94. HLH-94 therefore remains the recommended standard of care. Independently, we still recommend the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria. With regard to improved outcome of HSCT, there are already now promising results reported.32,56,57 Finally, because there is a need for improved pre-HSCT therapy, it would be valuable to perform a randomized study comparing 1 of the novel therapeutic approaches with the HLH-94/HLH-2004 concept updated with the knowledge reported here.

Note added in proof

After acceptance of the manuscript, the principal investigator was notified that 1 patient had to be withdrawn due to incorrect ethical approval in the corresponding country. The patient was a girl aged 54 days at start of therapy with biallelic STXBP2 mutations and in remission after 2 months who died treatment day 366 after relapse (no HSCT performed). Recalculations revealed that 368 patients were eligible with an estimated 5-year pSu of 62% (57%-67%).

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all reporting clinicians. They also thank Shinsaku Imashuku, Jorge Braier, David Webb, and Jacek Winiarski for valuable contributions to the protocol design. They are grateful for the invaluable contributions of their previous data managers Martina Löfstedt, Désirée Gavhed, and Tatiana von Bahr Greenwood, and Ida Hed Myrberg for statistical expertise.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, the Cancer and Allergy Foundation of Sweden, the Märta and Gunnar V Philipson Foundation, the Karolinska Institute, and Stockholm Country Council (ALF-project).

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.-I.H., A.H., M.A., R.M.E., A.H.F., G.J., S.L., and K.L.M. planned the study and recruited patients, with A.H. as study coordinator and J.-I.H. as principal investigator; I.A., E.I., K.L., M.M., V.N., and D.R. served as regional coordinators and recruited patients; S.M. provided epidemiologic advice; E.B. performed data entry and compiled data; and E.B., A.H., and J.-I.H. analyzed results and also wrote the manuscript, which was drafted by E.B. and reviewed and approved by all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.A. and J.-I.H. have been unpaid consultants to NovImmune. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

R.M.E. is retired from the Division of Hematology/Oncology, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada.

A.H.F. is retired from the Division of Bone Marrow Transplant and Immune Deficiency, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH.

Correspondence: Jan-Inge Henter, Childhood Cancer Research Unit, Karolinska University Hospital, SE-171 76 Stockholm, Sweden; e-mail: jan-inge.henter@ki.se.

References

- 1.Janka GE. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr. 1983;140(3):221-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. ; Histiocyte Society. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127(22):2672-2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stepp SE, Dufourcq-Lagelouse R, Le Deist F, et al. . Perforin gene defects in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Science. 1999;286(5446):1957-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldmann J, Callebaut I, Raposo G, et al. . Munc13-4 is essential for cytolytic granules fusion and is mutated in a form of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL3). Cell. 2003;115(4):461-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Côte M, Ménager MM, Burgess A, et al. . Munc18-2 deficiency causes familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 5 and impairs cytotoxic granule exocytosis in patient NK cells. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(12):3765-3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.zur Stadt U, Rohr J, Seifert W, et al. . Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 5 (FHL-5) is caused by mutations in Munc18-2 and impaired binding to syntaxin 11. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(4):482-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demirkol D, Yildizdas D, Bayrakci B, et al. ; Turkish Secondary HLH/MAS Critical Care Study Group. Hyperferritinemia in the critically ill child with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/sepsis/multiple organ dysfunction syndrome/macrophage activation syndrome: what is the treatment? Crit Care. 2012;16(2):R52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1503-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cetica V, Sieni E, Pende D, et al. . Genetic predisposition to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Report on 500 patients from the Italian registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(1):188-196.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henter JI, Ehrnst A, Andersson J, Elinder G. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and viral infections. Acta Paediatr. 1993;82(4):369-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. . HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henter JI, Aricò M, Egeler RM, et al. . HLH-94: a treatment protocol for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. HLH study group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28(5):342-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ost A, Nilsson-Ardnor S, Henter JI. Autopsy findings in 27 children with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Histopathology. 1998;32(4):310-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166(2):95-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horne A, Trottestam H, Aricò M, et al. ; Histiocyte Society. Frequency and spectrum of central nervous system involvement in 193 children with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(3):327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deiva K, Mahlaoui N, Beaudonnet F, et al. . CNS involvement at the onset of primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Neurology. 2012;78(15):1150-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer A, Cerf-Bensussan N, Blanche S, et al. . Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Pediatr. 1986;108(2):267-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jabado N, de Graeff-Meeder ER, Cavazzana-Calvo M, et al. . Treatment of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with bone marrow transplantation from HLA genetically nonidentical donors. Blood. 1997;90(12):4743-4748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dürken M, Horstmann M, Bieling P, et al. . Improved outcome in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis after bone marrow transplantation from related and unrelated donors: a single-centre experience of 12 patients. Br J Haematol. 1999;106(4):1052-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawa K, Sawada A, Sato M, et al. . Excellent outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic SCT with reduced-intensity conditioning for the treatment of chronic active EBV infection. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46(1):77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujiwara S, Kimura H, Imadome K, et al. . Current research on chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection in Japan. Pediatr Int. 2014;56(2):159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stéphan JL, Donadieu J, Ledeist F, Blanche S, Griscelli C, Fischer A. Treatment of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with antithymocyte globulins, steroids, and cyclosporin A. Blood. 1993;82(8):2319-2323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imashuku S, Hibi S, Ohara T, et al. ; Histiocyte Society. Effective control of Epstein-Barr virus-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with immunochemotherapy. Blood. 1999;93(6):1869-1874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henter JI, Samuelsson-Horne A, Aricò M, et al. ; Histocyte Society. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100(7):2367-2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahlaoui N, Ouachée-Chardin M, de Saint Basile G, et al. . Immunotherapy of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with antithymocyte globulins: a single-center retrospective report of 38 patients. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):e622-e628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trottestam H, Horne A, Aricò M, et al. ; Histiocyte Society. Chemoimmunotherapy for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: long-term results of the HLH-94 treatment protocol. Blood. 2011;118(17):4577-4584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aricò M, Janka G, Fischer A, et al. ; FHL Study Group of the Histiocyte Society. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Report of 122 children from the International Registry. Leukemia. 1996;10(2):197-203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horne A, Janka G, Maarten Egeler R, et al. ; Histiocyte Society. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(5):622-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trottestam H, Beutel K, Meeths M, et al. . Treatment of the X-linked lymphoproliferative, Griscelli and Chédiak-Higashi syndromes by HLH directed therapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(2):268-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalman VK, Klimpel GR. Cyclosporin A inhibits the production of gamma interferon (IFN gamma), but does not inhibit production of virus-induced IFN alpha/beta. Cell Immunol. 1983;78(1):122-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imashuku S, Hibi S, Kuriyama K, et al. . Management of severe neutropenia with cyclosporin during initial treatment of Epstein-Barr virus-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;36(3-4):339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper N, Rao K, Gilmour K, et al. . Stem cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2006;107(3):1233-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zur Stadt U, Beutel K, Weber B, Kabisch H, Schneppenheim R, Janka G A91V is a polymorphism in the perforin gene not causative of an FHLH phenotype. Blood. 2004;104(6):1909-1910. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Henter JI, Elinder G, Finkel Y, Söder O. Successful induction with chemotherapy including teniposide in familial erythrophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Lancet. 1986;2(8520):1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henter JI, Elinder G. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Clinical review based on the findings in seven children. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80(3):269-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson PA, Allen CE, Horton T, Jones JY, Vinks AA, McClain KL. Severe neurologic side effects in patients being treated for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(5):621-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee G, Lee SE, Ryu KH, Yoo ES. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in pediatric patients undergoing treatment for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: clinical outcomes and putative risk factors. Blood Res. 2013;48(4):258-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.İncecik F, Hergüner MO, Yıldızdaş D, et al. . Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome due to pulse methylprednisolone therapy in a child. Turk J Pediatr. 2013;55(4):455-457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrow SA, Rana R, Lee D, Paul T, Mahon JL Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome due to high dose corticosteroids for an MS relapse. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:325657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar S, Rajam L. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES/RPLS) during pulse steroid therapy in macrophage activation syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2011;78(8):1002-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balis FM, Lester CM, Chrousos GP, Heideman RL, Poplack DG. Differences in cerebrospinal fluid penetration of corticosteroids: possible relationship to the prevention of meningeal leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5(2):202-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fadeel B, Orrenius S, Henter JI. Induction of apoptosis and caspase activation in cells obtained from familial haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis patients. Br J Haematol. 1999;106(2):406-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson TS, Terrell CE, Millen SH, Katz JD, Hildeman DA, Jordan MB. Etoposide selectively ablates activated T cells to control the immunoregulatory disorder hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Immunol. 2014;192(1):84-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pui CH, Ribeiro RC, Hancock ML, et al. . Acute myeloid leukemia in children treated with epipodophyllotoxins for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(24):1682-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henter JI, Chow CB, Leung CW, Lau YL. Cytotoxic therapy for severe avian influenza A (H5N1) infection. Lancet. 2006;367(9513):870-873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marsh RA, Allen CE, McClain KL, et al. . Salvage therapy of refractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with alemtuzumab. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(1):101-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Benedetti F, Brunner HI, Ruperto N, et al. ; PRINTO; PRCSG. Randomized trial of tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2385-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teachey DT, Rheingold SR, Maude SL, et al. . Cytokine release syndrome after blinatumomab treatment related to abnormal macrophage activation and ameliorated with cytokine-directed therapy. Blood. 2013;121(26):5154-5157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Das R, Guan P, Sprague L, et al. . Janus kinase inhibition lessens inflammation and ameliorates disease in murine models of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2016;127(13):1666-1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maschalidi S, Sepulveda FE, Garrigue A, Fischer A, de Saint Basile G. Therapeutic effect of JAK1/2 blockade on the manifestations of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in mice. Blood. 2016;128(1):60-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henter JI, Elinder G, Söder O, Hansson M, Andersson B, Andersson U. Hypercytokinemia in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 1991;78(11):2918-2922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jordan MB, Hildeman D, Kappler J, Marrack P. An animal model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): CD8+ T cells and interferon gamma are essential for the disorder. Blood. 2004;104(3):735-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pachlopnik Schmid J, Ho CH, Chrétien F, et al. . Neutralization of IFNgamma defeats haemophagocytosis in LCMV-infected perforin- and Rab27a-deficient mice. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1(2):112-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu XJ, Tang YM, Song H, et al. . Diagnostic accuracy of a specific cytokine pattern in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children. J Pediatr. 2012;160(6):984-990.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marsh RA, Vaughn G, Kim MO, et al. . Reduced-intensity conditioning significantly improves survival of patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;116(26):5824-5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marsh RA, Kim MO, Liu C, et al. . An intermediate alemtuzumab schedule reduces the incidence of mixed chimerism following reduced-intensity conditioning hematopoietic cell transplantation for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(11):1625-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]