ABSTRACT

Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease (RNase A) is the founding member of the RNase A superfamily. Members of this superfamily of ribonucleases have high sequence diversity, but possess a similar structural fold, together with a conserved His-Lys-His catalytic triad and structural disulfide bonds. Until recently, RNase A proteins had exclusively been identified in eukaryotes within vertebrae. Here, we discuss the discovery by Batot et al. of a bacterial RNase A superfamily member, CdiA-CTYkris: a toxin that belongs to an inter-bacterial competition system from Yersinia kristensenii. CdiA-CTYkris exhibits the same structural fold as conventional RNase A family members and displays in vitro and in vivo ribonuclease activity. However, CdiA-CTYkris shares little to no sequence similarity with RNase A, and lacks the conserved disulfide bonds and catalytic triad of RNase A. Interestingly, the CdiA-CTYkris active site more closely resembles the active site composition of various eukaryotic endonucleases. Despite lacking sequence similarity to eukaryotic RNase A family members, CdiA-CTYkris does share high sequence similarity with numerous Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial proteins/domains. Nearly all of these bacterial homologs are toxins associated with virulence and bacterial competition, suggesting that the RNase A superfamily has a distinct bacterial subfamily branch, which likely arose by way of convergent evolution. Finally, RNase A interacts directly with the immunity protein of CdiA-CTYkris, thus the cognate immunity protein for the bacterial RNase A member could be engineered as a new eukaryotic RNase A inhibitor.

KEYWORDS: Angiogenin, bacterial competition, RNase A, contact-dependent growth inhibition, structural biology, toxin-immunity proteins

Review

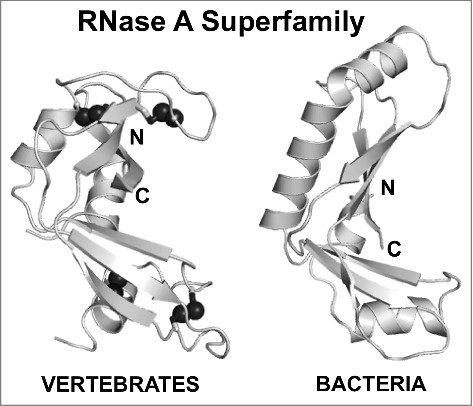

To date all identified RNase A superfamily members stem from vertebrates.1 These RNase A family members possess highly divergent sequences and play a variety of roles in many distinct biological pathways.1 As a result of their heterogeneous sequences, it is especially challenging to recognize and classify RNase A proteins in the absence of biochemical characterization. All previously identified RNase A proteins contain three to four conserved, structural disulfide bonds (Fig. 1). RNase A proteins act on RNA to catalyze a phosphotransferase bond cleavage to produce a cyclic 2′–3′-phosphodiester fragment and a 5′-hydroxyl terminated fragment.2,3 While some RNase A members can degrade both single and double-stranded RNAs, the preferred substrate for catalysis is single-stranded RNA.1 Typically, poly-pyrimidine strands are more rapidly cleaved than poly-purine RNAs, and a conserved His-Lys-His catalytic triad is required for the hydrolytic activity to occur.2

Figure 1.

The RNase A superfamily has two divergent branches: one in vertebrates and a recently identified bacterial branch. Notably the disulfide bonds (black spheres) present in all vertebrate RNase A family members (RNase 1 – PDB ID 3TSR18) are absent in bacterial RNase A proteins (CdiA-CTYrkis – PDB ID 5E3E15). The N- and C- termini are indicated. Figures were generated in PyMOL.

Bacteria possess many pathways to compete and communicate with their bacterial neighbors. One such system is contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI), which is found in Gram-negative bacteria that exchange toxins upon direct cell-to-cell contact.4,5 CDI relies on a two-partner (Type V) secretion system comprised of CdiA and CdiB. CdiB, an Omp85 β-barrel, is responsible for the export and display of CdiA on the cell surface. CdiA proteins are large (180–630 kDa). They recognize specific surface receptors of neighboring bacteria, and upon contact, initiate transfer of the CdiA C-terminal toxin domain (CdiA-CT) into the target cell.5-7 A single gene cluster encodes CdiA and CdiB, as well as CdiI, the cognate immunity protein.5,8 CdiI proteins specifically bind and restrict the activity of cognate CdiA-CT toxin domains, providing species-specific protection.5,8

To date, nearly all characterized CDI toxins are nucleases, each with its own specificity. For example, the CdiA-CT of Enterobacter cloacae cleaves 16S ribosomal RNA,9 while uropathogenic E. coli 536 bears a unique ribonuclease fold with no sequence similarity to other RNase families and only cleaves tRNA in the presence of endogenous O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase (CysK).10,11 Additionally, several CdiA-CT toxins belong to the PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase superfamily. These include a Zn2+-dependent DNase from E. coli TA271,12,13 as well as CdiA-CTs from Burkholderia pseudomallei 1026b and E479, both of which are tRNases that specifically recognize a unique subset of tRNAs and cleave at different tRNA sites.12,14

Often the structure of an uncharacterized protein provides insight into its precise function. Recently, the crystal structure of Yersinia kristensenii ATCC 33638 CdiA-CT toxin (CdiA-CTYkris) in complex with its immunity protein (CdiIYkris) was determined (PDB ID 5E3E).15 The toxin structure adopts a kidney shape that is formed by two curved β-sheet domains, which strongly resembles several RNase A family members: human angiogenin (PDB ID 4B3616), Rana pipiens protein P-30 or onconase (PDB ID 3SNF17), and mouse pancreatic RNase A (RNase 1, PDB ID 3TSR18). Strikingly, while eukaroytic RNase A family members contain 3 to 4 conserved disulfide bonds, CdiA-CTYkris contains none at all (Fig. 1).

In addition to lacking some structural elements that are highly conserved among eukaryotic RNase A homologs, the composition of the catalytic core of CdiA-CTYkris is distinct from the typical RNase A His-Lys-His catalytic triad. In angiogenin, the reaction is initiated when His13, acting as a general base, deprotonates the 2′ hydroxyl of substrate RNA.2 Lys40 stabilizes the resulting transition state intermediate, and, acting as a general acid, His116 terminates the reaction by donating a proton to the 5′ leaving group.2 From structural alignments with RNase A proteins, the active site of CdiA-CTYkris was predicted to comprise of His175 (aligns to His13), Val192 (aligns to Lys40), and Thr276 or Tyr278 (aligns to His116). As Val192 is unlikely to participate in catalysis, Batot et al. identified the neighboring residue Arg186, which appears to be conserved as shown by multiple sequence alignments of putative bacterial homologs,15 as a potential transition state stabilizer.

Further, experiments show that CdiA-CTYkris has metal-independent RNase activity. However, in the presence of the immunity protein, CdiIYkris, a toxin-immunity complex is formed that effectively neutralizes CdiA-CTYkris ribonuclease activity. Notably, the CdiA-CTYkris variants H175A and Y278A display no RNase activity both in vitro and in vivo, whereas R186A and T276A variants retain partial RNase activity. Like RNase A, CdiA-CTYkris can also hydrolyze cCMP.3 All four of the H175A, R186A, T276A and Y278A CdiA-CTYkris variants exhibited reduced cCMP hydrolytic activity. These results suggest that His175, Arg186, Thr276 and Tyr278 residues are required for full CdiA-CTYkris ribonuclease activity. The RNase and cCMP hydrolytic activities of CdiA-CTYkris, in addition to its structural similarity to the RNase A family members, support its classification as a novel bacterial member of the RNase A superfamily.

The distinct set of catalytic/active site residues for CdiA-CTYkris suggest an alternate mechanism of ribonuclease action. The reaction likely begins via His175, which may behave as a general base to initiate the reaction. Subsequently, Arg186 could stabilize the transition state while Thr276 or Tyr278, acting as a general acid, terminate the reaction. Though distinct from other RNase A family members, aspects of this unique catalytic core have been observed in other endonuclease families. For example, the RNase T1 family of nucleases employ a highly conserved arginine residue to stabilize the reaction intermediate.19 Further, tRNA-splicing endonucleases use a tyrosine residue as a general base to initiate the reaction, and a histidine residue to terminate the reaction by acting as a general acid.20 Similarly, tyrosine appears to be involved in the reaction mechanism of other eukaryotic endonucleases, RNase L and Ire1, acting by an analogous mechanism to tRNA-splicing.21 While the proposed catalytic residues of bacterial CdiA-CTYkris have been observed in other nucleases, they signify a dramatic shift from the conserved His-Lys-His core of eukaryotic RNase A family members. Further biochemical analyses are required to understand the RNase mechanism of CdiA-CTYkris; notably characterizing the pKa of key residues could aid in understanding specific residue roles in general acid/base chemistry. Further, little is known about the substrate specificity of CdiA-CTYkris and whether its unique catalytic core, as compared with eukaryotic RNAse A, affects its RNA substrate specificity.

Before the characterization of this CdiA-CTYkris toxin,15 RNase A family members had only been discovered in vertebrates.1 Placing CdiA-CTYkris as a member of the RNase A family allows for the integration of a novel and populous bacterial branch into this superfamily. Based on sequence homology to CdiA-CTYkris, this subfamily includes a multitude of bacterial proteins/domains from both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, many of which play a role in bacterial virulence or competition and all of which have predicted immunity proteins and associated secretion systems.15 CdiA proteins from Serratia proteamaculans, Photorhabdus luminescens, Pseudomonas citronellolis, and Bordetella species contain RNase A-like C-terminal toxin domains. Many of the CdiA-CTYkris homologs are associated with type VI secretion systems (T6SS); the RNase domain is found in T6SS effectors in Burkholderia and Enterobacteria species as well as in Rhs (Rearrangement hotspot) proteins – which are exported by T6SS – in Pseudomonas and other species.22,23 The RNase domain is also present in Gram-positive Bacillus lipoproteins and at the C-terminus of putative type VII secretion system (T7SS) effectors.24-26

Because members of this branch of bacterial RNase A proteins are frequently association with a secretion system, these toxins are presumably unfolded and refolded during the secretion/delivery process. As such, the lack of disulfide bonds in bacterial RNase A proteins offers a practical advantage; the proteins can be readily unfolded and refolded without the need to break or reform disulfide bonds. Regarding catalysis, the predicted CdiA-CTYkris His-Arg-Tyr-Thr active site residues are well conserved across these homologs: His175 and Thr276 are completely conserved, while a phenylalanine residue is frequently substituted for Tyr278. Thus, it seems likely that there is a common active site amongst these bacterial RNase A family members, though Thr276 is perhaps less likely to play a role in catalysis than Tyr278. In conclusion, further mechanistic analysis of CdiA-CTYkris residues involved in ribonuclease activity is required.

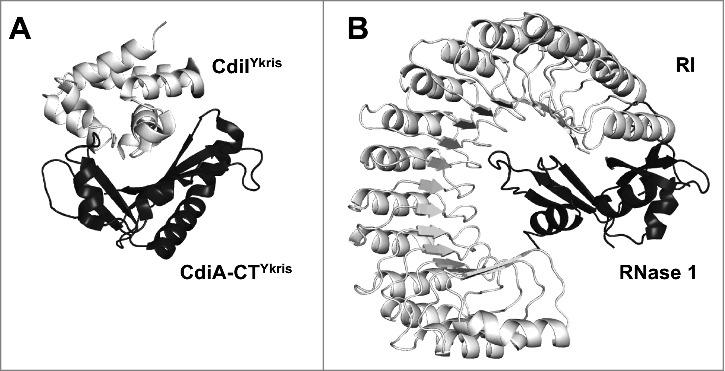

Most CdiA-CTYkris bacterial homologs are encoded near putative immunity proteins. While eukaryotic RNase A family members do not encode a neighboring immunity protein, the RNase A inhibitor (RI) is abundant in the eukaryotic cytoplasm to prevent RNase cytotoxicity.27 Interestingly, there is no sequence or structural similarity between CdiIYkris and RI (Fig. 2). While CdiIYkris is nearly spherical, composed of eight densely packed α-helices,15 RI resembles an horseshoe, with a structural repeat of alternating α-helices and β-strands that form a curved, right-handed solenoid consisting of 15 leucine-rich repeats.18 Unlike RI, which surrounds mouse pancreatic RNase A (RNase 1, Fig. 2B), CdiIYkris interacts directly with CdiA-CTYkris active site residues (Fig. 2A); hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions are formed between CdiIYkris Gln20 and CdiA-CTYkris Tyr278, and CdiIYkris Asp21 and CdiA-CTYkris His175 and Thr276. Thus, it seems likely that CdiIYkris protects against CdiA-CTYkris action by restricting the access of substrates to the toxin's active site. Although CdiIYkris has no sequence or structural similarity to RI (Fig. 2), preliminary experiments demonstrate that CdiIYkris co-purifies with and partially inactivates eukaryotic RNase A (unpublished data, personal communication). CdiA-CTYkris and eukaryotic RNase A are dramatically different proteins with low sequence similarity and key differences in their active site composition and geometry. Thus, the ability of CdiI to inhibit eukaryotic RNase A is remarkable and could have significant implications. As CdiIYkris interacts specifically with CdiA-CTYkris active site residues, CdiIYkris could be engineered to bind specific RNase A proteins with high affinity. This could be advantageous as the CdiIYkris protein is small (∼11 kDa) and can be recombinantly produced and purified from bacteria, while RI, a larger protein (∼50 kDa) with numerous cysteine residues, is typically extracted from animal tissue. Engineering CdiIYkris to have both high affinity and neutralizing power for eukaryotic RNase A proteins, together with its ease in expression and purification from bacterial systems, would significantly reduce the cost of a potential RNase A inhibitor for laboratory usage.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the interaction between (A) CdiA-CTYkris and its immunity protein CdiI (PDB ID 5E3E15) with the interaction of (B) mouse pancreatic RNase 1 with mouse RNase inhibitor (RI) (PDB ID 3TSR18). CdiIYkris interacts directly with the active site residues of CdiA-CTYkris. Alternatively, the RI, composed entirely of leucine-rich repeats, essentially wraps itself around RNase 1, effectively encapsulating the active site and much of the RNase A protein. Differences between the CdiA-CT/CdiIYkris and RNase 1-RI interactions are reflected in quite different buried surface areas of 12,500 and 23,700 Å2, respectively.28

Significantly, Batot et al. have discovered a diverse new branch of the RNase A superfamily in bacteria.15 As the RNase A superfamily has no sequence homologs in lower eukaryotes or invertebrates, and this unique bacterial subset of RNase A toxins has no sequence similarity to the vertebrate RNase A proteins, the bacterial and eukaryotic RNase A branches seem indicative of convergent evolution. Thus, bacteria appear to have independently evolved an analogous ribonuclease that – while structurally somewhat similar to eukaryotic RNase A family members – operates via a novel mechanism. While vertebrate RNase A family members cleave RNA using a His-Lys-His catalytic triad, bacterial RNase A family members appear to utilize a His-Arg-(Tyr/Thr) triad or quartet. Further, the structure of CdiA-CTYkris was solved in complex with its immunity protein CdiIYkris, which incidentally can also partially neutralize RNase A activity (unpublished). It is remarkable that CdiIYkris, a highly specific protein partner for CdiA-CTYkris, may also neutralize a protein from another species with a similar function to CdiA-CTYkris, but with no detectable sequence similarity and different active site architecture. The broadly neutralizing ability of CdiIYkris could be harnessed to generate effective RNase A inhibitors at low cost for laboratory or industrial settings.

References

- 1.Dyer KD, Rosenberg HF. The RNase a superfamily: Generation of diversity and innate host defense. Mol Diversity. 2006;10:585–97. doi: 10.1007/s11030-006-9028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuchillo CM, Nogues MV, Raines RT. Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: fifty years of the first enzymatic reaction mechanism. Biochemistry. 2011;50:7835–41. doi: 10.1021/bi201075b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raines RT. Ribonuclease A. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1045–65. doi: 10.1021/cr960427h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki SK, Pamma R, Hernday AD, Bickham JE, Braaten BA, Low DA. Contact-dependent inhibition of growth in Escherichia coli. Science. 2005;309:1245–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1115109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willett JL, Ruhe ZC, Goulding CW, Low DA, Hayes CS. Contact-Dependent Growth Inhibition (CDI) and CdiB/CdiA Two-Partner Secretion Proteins. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:3754–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruhe ZC, Wallace AB, Low DA, Hayes CS. Receptor polymorphism restricts contact-dependent growth inhibition to members of the same species. MBio. 2013;4. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00480-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willett JL, Gucinski GC, Fatherree JP, Low DA, Hayes CS. Contact-dependent growth inhibition toxins exploit multiple independent cell-entry pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:11341–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512124112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aoki SK, Diner EJ, de Roodenbeke CT, Burgess BR, Poole SJ, Braaten BA, Jones AM, Webb JS, Hayes CS, Cotter PA, et al.. A widespread family of polymorphic contact-dependent toxin delivery systems in bacteria. Nature. 2010;468:439–42. doi: 10.1038/nature09490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck CM, Morse RP, Cunningham DA, Iniguez A, Low DA, Goulding CW, Hayes CS. CdiA from Enterobacter cloacae delivers a toxic ribosomal RNase into target bacteria. Structure. 2014;22:707–18. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diner EJ, Beck CM, Webb JS, Low DA, Hayes CS. Identification of a target cell permissive factor required for contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI). Genes Dev. 2012;26:515–25. doi: 10.1101/gad.182345.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson PM, Beck CM, Morse RP, Garza-Sanchez F, Low DA, Hayes CS, Goulding CW. Unraveling the essential role of CysK in CDI toxin activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:9792–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607112113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morse RP, Nikolakakis KC, Willett JL, Gerrick E, Low DA, Hayes CS, Goulding CW. Structural basis of toxicity and immunity in contact-dependent growth inhibition (CDI) systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:21480–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216238110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morse RP, Willett JL, Johnson PM, Zheng J, Credali A, Iniguez A, Nowick JS, Hayes CS, Goulding CW. Diversification of beta-Augmentation Interactions between CDI Toxin/Immunity Proteins. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:3766–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson PM, Gucinski GC, Garza-Sanchez F, Wong T, Hung LW, Hayes CS, Goulding CW. Functional Diversity of Cytotoxic tRNase/Immunity Protein Complexes from Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:19387–400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.736074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batot G, Michalska K, Ekberg G, Irimpan EM, Joachimiak G, Jedrzejczak R, Babnigg G, Hayes CS, Joachimiak A, Goulding CW. The CDI toxin of Yersinia kristensenii is a novel bacterial member of the RNase A superfamily. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:5013–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thiyagarajan N, Acharya KR. Crystal structure of human angiogenin with an engineered loop exhibits conformational flexibility at the functional regions of the molecule. FEBS Open Bio. 2013;3:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holloway DE, Singh UP, Shogen K, Acharya KR. Crystal structure of Onconase at 1.1 angstrom resolution – insights into substrate binding and collective motion. Febs J. 2011;278:4136–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomax JE, Bianchetti CM, Chang A, Phillips GN Jr, Fox BG, Raines RT. Functional evolution of ribonuclease inhibitor: insights from birds and reptiles. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:3041–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida H. The ribonuclease T1 family. Ribonucleases, Pt A. 2001;341:28–41. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(01)41143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue S, Calvin K, Li H. RNA recognition and cleavage by a splicing endonuclease. Science. 2006;312:906–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1126629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee KPK, Dey M, Neculai D, Cao C, Dever TE, Sicheri F. Structure of the dual enzyme ire1 reveals the basis for catalysis and regulation in nonconventional RNA splicing. Cell. 2008;132:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diniz JA, Coulthurst SJ. Intraspecies Competition in Serratia marcescens Is Mediated by Type VI-Secreted Rhs Effectors and a Conserved Effector-Associated Accessory Protein. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:2350–60. doi: 10.1128/JB.00199-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koskiniemi S, Lamoureux JG, Nikolakakis KC, t'Kint de Roodenbeke C, Kaplan MD, Low DA, Hayes CS. Rhs proteins from diverse bacteria mediate intercellular competition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7032–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300627110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao ZP, Casabona MG, Kneuper H, Chalmers JD, Palmer T. The type VII secretion system of Staphylococcus aureus secretes a nuclease toxin that targets competitor bacteria. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16183. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holberger LE, Garza-Sanchez F, Lamoureux J, Low DA, Hayes CS. A novel family of toxin/antitoxin proteins in Bacillus species. Febs Letters. 2012;586:132–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohr RJ, Anderson M, Shi MM, Schneewind O, Missiakas D. EssD, a Nuclease Effector of the Staphylococcus aureus ESS Pathway. J Bacteriol. 2017;199:e00528-16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00528-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickson KA, Haigis MC, Raines RT. Ribonuclease inhibitor: structure and function. Progress Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2005; 80:349–74. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(05)80009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]