Abstract

Objective

Our population-based research aimed to clarify the association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and mortality risk in patients with lung cancer.

Design

Retrospective cohort study

Setting

National health insurance research database in Taiwan

Participants

All (n=1 37 077) Taiwanese residents who were diagnosed with lung cancer between 1997 and 2012 were identified. Eligible patients with baseline CKD (n=2269) were matched with controls (1:4, n=9076) without renal disease according to age, sex and the index day of lung cancer diagnosis.

Methods

The cumulative incidence of death was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the risk determinants were explored by the Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

Mortality occurred in 1866 (82.24%) and 7135 (78.61%) patients with and without CKD, respectively (P=0.0001). The cumulative incidences of mortality in patients with and without chronic renal disease were 72.8% vs 61.6% at 1 year, 82.0% vs 76.6% at 2 years and 88.9% vs 87.2% at 5 years, respectively. After adjusting for multiple confounding factors including age and comorbidities, Cox regression analysis revealed that CKD was associated with an increased risk of mortality (adjusted HR 1.38; 95% CI 1.29 to 1.47). Stratified analysis further showed that the association was consistent across patient subgroups.

Conclusion

Comorbidity associated with CKD is a risk factor for mortality in patients with lung cancer.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, lung cancer, mortality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There were population-based data to perform a longitudinal assessment of mortality risk in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Some important information, such as the cancer stage, driver mutation status, performance status, smoking history and treatment options, was not available in the database.

Patients with more severe CKD may be less likely to receive aggressive diagnostic procedures or biopsy, resulting in lead-time bias.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide. Severity of underlying comorbidities has been reported to impact the prognosis of a variety of cancers, including early stage or late-stage lung cancer.1–3Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been found to be a major risk factor for mortality in patients with various types of malignancy, but its impact on lung cancer has not been elucidated.4

Current literature pertaining to the association between CKD and prognosis of lung cancer is sparse and controversial. After retrospectively studying 107 patients with lung cancer with CKD, Patel et al concluded that these patients had a similar clinical course and survival as compared with those without CKD.5 In a large retrospective analysis involving 8223 patients with cancer with and without CKD, Na et al found that CKD was unrelated to mortality risk in patients with lung or breast cancer, although it was associated with risk of death in other cancer types.6 In contrast, Cenik et al found that renal function might be inversely associated with survival in 298 patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The univariate analysis demonstrated that higher baseline, nadir and median calculated creatinine clearance were associated with worse overall survival, although the multivariate-adjusted association was insignificant.7

In light of the ongoing controversy regarding this issue, we conducted a nationwide population-based cohort study to clarify the impact of CKD on mortality in patients with lung cancer.

Patients and methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study based on analysis of the entire Taiwanese population. The Taiwan Department of Health had placed all public insurance systems under the National Health Insurance programme since 1995 to cover healthcare of all residents, and had achieved an actual coverage of more than 99%. All the registry and claim data were comprehensively archived in the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) for research purposes. Diseases were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). This nationwide population-based study was approved by the institutional review board of E-Da Hospital (EMRP-103–011; EMRP-103–012) as well as the Taiwan National Health Research Institute (NHIRD-103–116), and permission to extract and analyse NHIRD was provided.

Patient identification and selection

All individuals diagnosed with lung cancer (ICD-9-CM code: 162.X) between 1997 and 2012 were screened for eligibility. The diagnosis of lung cancer was ascertained by certification in the Registry of Catastrophic Illness Database (RCID), a subsection of NHIRD. Because the certificate of catastrophic illness exempts the insured patients from co-payment, it is meticulously regulated and audited by the government. Malignant diseases including lung cancer are statutorily included in RCID.

After identification, patients were further categorised according to the presence of CKD prior to the diagnosis of lung cancer. The presence of CKD was determined from specific ICD codes (ICD-9-CM=403.11, 403.91, 404.02, 404.03, 404.12, 404.13, 404.92, 404.93, 585.X, 586.X) and one of the following criteria: (1) three or more outpatient visits within a 6-month period, each with a diagnosis of CKD; or (2) inpatients with diagnosis of CKD on admission. Index days for the two cohorts were taken as the dates of lung cancer diagnosis. One patient with baseline CKD was matched with four patients without CKD according to age, sex and the index day. Patients with another cancer diagnosis before the index day were excluded.

Assessment of comorbidities and confounding factors

Comorbidities were based on diagnostic codes and classified as those existing prior to the index day and included hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), cholelithiasis and hyperlipidaemia. Type of surgical intervention was also analysed as a confounding factor.

Outcome measurement and risk factor analysis

All the study participants were followed until the occurrence of death or the end of 2012, whichever came first. We defined occurrence of death as the date of withdrawal from the National Health Insurance programme. Withdrawal from the insurance programme could only result from death or emigration, and emigration is negligible in these patients with lung cancer. Differences in the baseline characteristics of the two study cohorts were compared by Student’s t-test for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables, respectively. The cumulative incidence of death was calculated by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, and the between-group difference was examined by the log-rank test. The association between CKD and risk of death was assessed by Cox’s proportional hazards model adjusted for age, type of surgery and multiple comorbidities. Cox HRs were computed along with the 95% CI. We further performed stratified analysis to explore possible interactions between CKD and another baseline condition in terms of their effect on mortality risk. All statistical tests were two-sided, with statistical significance set at a P value of 0.05 or less. All analyses were performed using SAS software, V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

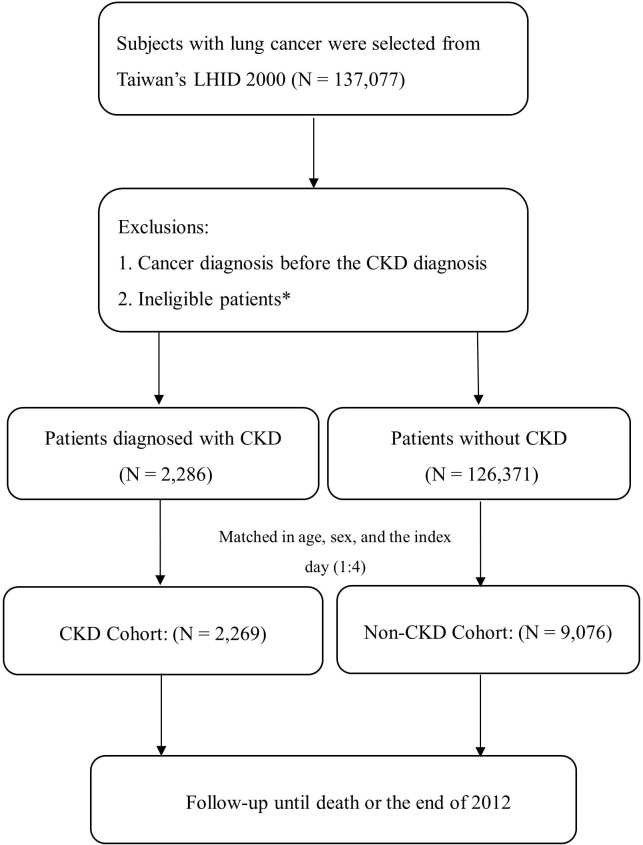

The study flow is summarised in figure 1. A total of 137 077 subjects with lung cancer were enrolled for analysis. Among them, we identified 2269 individuals with CKD and 9076 controls without CKD for analysis. Characteristics of the study subjects are summarised in table 1. The CKD cohort was less likely to receive surgical treatment as compared with its non-CKD counterpart (10.31% vs 14.11%, P<0.0001). On the other hand, more patients with CKD were comorbid with another chronic illness like hypertension, DM, COPD, CHF, cholelithiasis and hyperlipidaemia (P<0.0001).

Figure 1.

The study flow chart of patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer with and without CKD. *including significant data error. CKD, chronic kidney disease; LHID 2000, Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

| Non-CKD cohort (n=9076) | CKD cohort (n=2269) | P value | |

| Age (mean±SD) | 74.65±8.32 | 74.71±8.33 | 0.8707 |

| Age group, years | 0.9922 | ||

| <65 | 868 (9.56%) | 218 (9.61%) | |

| 65–79 | 5385 (59.33%) | 1343 (59.19%) | |

| ≧80 | 2833 (31.10%) | 708 (31.20%) | |

| Sex | 1.0000 | ||

| Female | 2444 (26.93%) | 611 (26.93%) | |

| Male | 6632 (73.07%) | 1658 (73.07%) | |

| Surgery | 1281 (14.11%) | 234 (10.31%) | <0.0001 |

| Wedge or partial resection | 228 (2.51%) | 45 (1.98%) | 0.1415 |

| Lobectomy | 460 (5.07%) | 59 (2.60%) | <0.0001 |

| Bilobectomy | 14 (0.15%) | 2 (0.09%) | 0.4525 |

| Pneumonectomy, total | 35 (0.39%) | 1 (0.04%) | 0.0097 |

| Sleeve resection | 8 (0.09%) | 3 (0.13%) | 0.5463 |

| Thoracoscopic pneumonectomy | 4 (0.04%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0.3172 |

| Thoracoscopic lobectomy | 401 (4.42%) | 76 (3.35%) | 0.0233 |

| Thoracoscopic wedge resection | 282 (3.11%) | 72 (3.17%) | 0.8713 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 3442 (37.92%) | 1710 (75.36%) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1555 (17.13%) | 937 (41.30%) | <0.0001 |

| COPD | 2180 (24.02%) | 737 (32.48%) | <0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 508 (5.60%) | 550 (24.24%) | <0.0001 |

| Cholelithiasis | 498 (5.49%) | 212 (9.34%) | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 558 (6.15%) | 356 (15.69%) | <0.0001 |

| Outcome | |||

| Death | 7135 (78.61%) | 1866 (82.24%) | 0.0001 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Incidence of mortality in patients with lung cancer with and without CKD

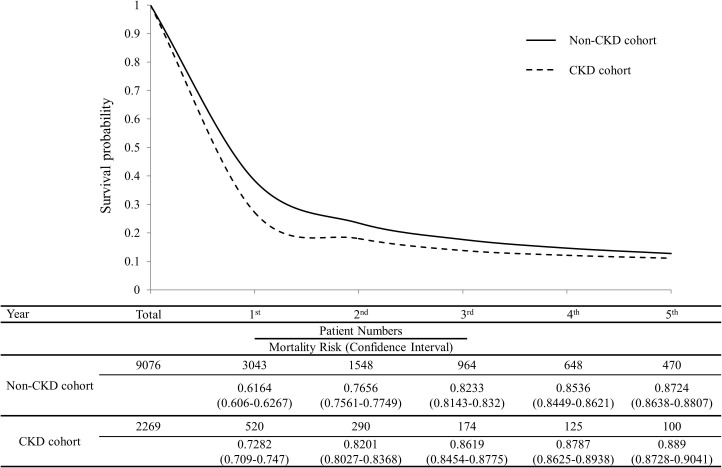

During the follow-up period, there were 1866 (82.24%) and 7135 (78.61%) deaths in the CKD and the non-CKD cohorts, respectively (P=0.0001). Figure 2 illustrates the survival curves in patients with and without CKD. The cumulative incidences of mortality between the CKD and non-CKD cohorts were 72.8% vs 61.6% at 1 year, 82.0% vs 76.6% at 2 years, 86.2% vs 82.3% at 3 years and 88.9% vs 87.2% at 5 years, respectively. The mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with CKD in the initial 4 years, during which period 88% and 85% of deaths occurred in the CKD and non-CKD cohorts, respectively.

Figure 2.

Survival curves for the chronic kidney disease (CKD) and non-CKD cohorts.

Multivariable Cox analysis between CKD and mortality in patients with lung cancer

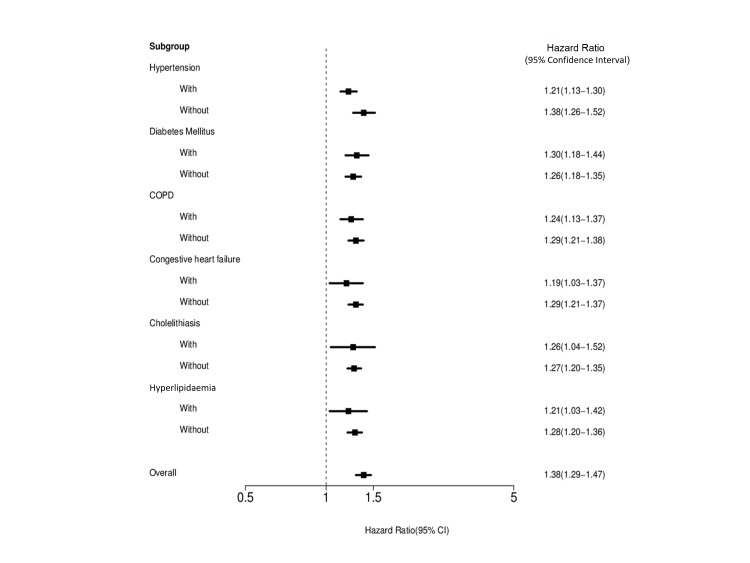

As shown in table 2, multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis revealed that CKD was associated with an increased risk of mortality (adjusted HR 1.38; 95% CI 1.29 to 1.47, P=0.0074). Older age and other comorbidities including DM, COPD, CHF and dyslipidaemia were also risk factors for mortality. In contrast, surgical treatment was associated with a reduction in the risk of death (adjusted HR 0.24; 95% CI 0.21 to 0.27, P<0.0001). The Forest plot in figure 3 depicts the impact of CKD on mortality risk in various strata according to baseline characteristics. The result revealed that CKD was consistently associated with an increased risk of death across various patient subgroups.

Table 2.

Results of multivariable Cox proportional hazards model analysis for an association between CKD and the risk of death

| Crude HR | Adjusted HR | |||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| CKD versus non-CKD | 1.46 (1.38 to 1.55) | <0.0001 | 1.38 (1.29 to 1.47) | 0.0074 |

| Age | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.07) | 0.9045 | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.14) | 0.0010 |

| Surgery | 0.24 (0.21 to 0.26) | <0.0001 | 0.24 (0.21 to 0.27) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 1.09 (1.03 to 1.15) | 0.0021 | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.06) | 0.8231 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.24 (1.16 to 1.32) | <0.0001 | 1.12 (1.05 to 1.21) | 0.0013 |

| COPD | 1.13 (1.07 to 1.21) | <0.0001 | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.16) | 0.0098 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.44 (1.31 to 1.57) | <0.0001 | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.30) | 0.0007 |

| Cholelithiasis | 1.13 (1.01 to 1.26) | 0.0269 | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.25) | 0.0564 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.07) | 0.531 | 0.83 (0.75 to 0.93) | 0.0008 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 3.

Stratified analyses for the association between chronic kidney disease and mortality risk. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

In this study, we found that CKD is a prognostic factor for 5-year mortality in patients with lung cancer. The association remained significant after adjustment for other comorbidities and risk factors. We further illustrated that the impact of CKD on the risk of death was predominantly confined to the initial 4 years.

The presence of CKD may restrict therapeutic options in lung cancer, resulting in suboptimal management and thereby accounting for the increased risk of death. For instance, platinum-based chemotherapy is the cornerstone for the treatment of small cell lung cancer as well as advanced NSCLC without a driver mutation. In patients with CKD, carboplatin is often substituted for cisplatin because of less renal toxicity. Nonetheless, current evidence suggests that cisplatin is associated with a higher objective response rate than carboplatin, although the survival benefit may be small.8 Similarly, pemetrexed, an important chemotherapeutic agent that can be used in the initial, maintenance and second-line treatment of NSCLC, is not recommended in patients with creatinine clearance <45 mL/minute.9 In addition to restricting treatment options, CKD itself has been shown to incur an increased risk of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality, probably resulting from upregulated inflammation and coagulation.10–12

Comorbidity has a major impact on survival in early stage and late-stage lung cancer.3 Iachina et al conducted a population-based study to examine the impact of comorbidity on the survival of patients with NSCLC, and concluded that comorbidity has a significant indirect effect on survival, which is mediated by the resection process and a slightly direct effect on mortality.2 In this study, comorbidities (including hypertension, DM, COPD, CHF, cholelithiasis and hyperlipidaemia) were associated with the risk of death. On stratified Cox regression analysis for the comorbidities, CKD was found to be an independent risk factor for 5-year mortality.

In the present study, surgery was associated with a reduced risk of death in patients with lung cancer. Surgical resection, either by thoracotomy or by thoracoscopy, is the mainstay of treatment for patients with early stage lung cancer. Since tumour stage information was not available for the study population, the various types of surgical resection could represent early stage disease, and good performance status indicated a better prognosis. In the present study, more patients in the non-CKD group received surgery (14.11% vs 10.31% in the CKD group), mainly owing to fewer comorbidities and likelihood of a better performance status.

Sex was also an important risk factor in lung cancer mortality. This is consistent with a retrospective study conducted by Sakurai et al, which showed women with NSCLC, especially with an adenocarcinoma histology, had better survival than men.13 In that study, women were more likely to have adenocarcinoma and stage IA disease, which might account for the better prognosis in women. A meta-analysis conducted by Nakamura et al also indicated a significantly better survival for women.14 However, the reasons why women with lung cancer live significantly longer than men remain elusive.

Age was another risk factor for mortality in lung cancer. Despite the high incidence of lung cancer and high mortality rate in elderly patients, the likelihood of receiving active treatment, including surgery and chemotherapy, appears to decrease with increasing age.15 A retrospective study conducted by Blanco et al found that age and comorbidities have a significant impact on treatment choice, but only the presence of more than one comorbid condition worsens prognosis.16 In the current study, age was also a predictor of mortality according to multivariable Cox analysis.

The strength of our study was its use of population-based data to perform a longitudinal assessment of mortality risk in patients with CKD. It is highly representative of the general population and minimised the likelihood of selection bias. The major limitation of this study was that some important information, such as the cancer stage, driver mutation status, performance status, smoking history and treatment options (radiotherapy, chemotherapy or target therapy), was not available in the database. Bias resulting from unknown confounders may have affected our results. In addition, patients with more severe CKD may be less likely to receive aggressive diagnostic procedures or biopsy, resulting in lead-time bias, which might delay cancer diagnosis and shorten survival. Moreover, extrapolation to other populations warrants caution and may require validation given that the characteristics of lung cancer such as subtype of pathology, proportions of never smokers and genetic predisposition differ between the East and the West.17 Finally, the treatment of lung cancer has been rapidly advancing and our findings may not be generalisable to patients who receive agents unavailable during the study period, such as anaplastic lymphoma kinase or immune checkpoint inhibitors. It deserves further research to explore how comorbidity with CKD may influence the prognosis of lung cancer as the management continues to evolve.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that CKD was independently associated with increased mortality in patients with lung cancer. Clinicians should be aware of CKD as a predictor for poor outcome and should make efforts to preserve renal function in patients with lung cancer. Further investigation may be needed to corroborate the correlation or bring up reliable reasons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Center for Database Research, E-Da Hospital, for data management and statistical analysis support.

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-FW wrote the manuscript. J-YC modified the manuscript content and submitted the paper. H-SL, J-TW and C-KH were involved with data management. Y-CH reviewed and modified the manuscript content.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data from the study.

References

- 1. Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, et al. . Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA 2004;291:2441–7. 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iachina M, Green A, Jakobsen E. The direct and indirect impact of comorbidity on the survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a combination of survival, staging and resection models with missing measurements in covariates. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003846 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tammemagi CM, Neslund-Dudas C, Simoff M, et al. . Impact of comorbidity on lung cancer survival. Int J Cancer 2003;103:792–802. 10.1002/ijc.10882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weng PH, Hung KY, Huang HL, et al. . Cancer-specific mortality in chronic kidney disease: longitudinal follow-up of a large cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:1121–8. 10.2215/CJN.09011010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patel P, Henry LL, Ganti AK, et al. . Clinical course of lung cancer in patients with chronic kidney disease. Lung Cancer 2004;43:297–300. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Na SY, Sung JY, Chang JH, et al. . Chronic kidney disease in cancer patients: an independent predictor of cancer-specific mortality. Am J Nephrol 2011;33:121–30. 10.1159/000323740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kutluk Cenik B, Sun H, Gerber DE. Impact of renal function on treatment options and outcomes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2013;80:326–32. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ardizzoni A, Boni L, Tiseo M, et al. . Cisplatin- versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:847–57. 10.1093/jnci/djk196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eli Lilly and Company. Alimta (pemetrexed) [prescribing information]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Königsbrügge O, Lötsch F, Zielinski C, et al. . Chronic kidney disease in patients with cancer and its association with occurrence of venous thromboembolism and mortality. Thromb Res 2014;134:44–9. 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stenvinkel P, Heimbürger O, Paultre F, et al. . Strong association between malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerosis in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int 1999;55:1899–911. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Crump C, et al. . Elevations of inflammatory and procoagulant biomarkers in elderly persons with renal insufficiency. Circulation 2003;107:87–92. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000042700.48769.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sakurai H, Asamura H, Goya T, et al. . Survival differences by gender for resected non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis of 12,509 cases in a Japanese Lung Cancer Registry study. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1594–601. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f1923b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakamura H, Ando K, Shinmyo T, et al. . Female gender is an independent prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;17:469–80. 10.5761/atcs.oa.10.01637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weinmann M, Jeremic B, Toomes H, et al. . Treatment of lung cancer in the elderly. Part I: non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2003;39:233–53. 10.1016/S0169-5002(02)00454-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blanco JA, Toste IS, Alvarez RF, et al. . Age, comorbidity, treatment decision and prognosis in lung cancer. Age Ageing 2008;37:715–8. 10.1093/ageing/afn226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu YL, Zhou Q. Lung cancer management in the Asia-Pacific region: what’s the difference compared with the United States and Europe? Results of the Second Asia Pacific Lung Cancer Conference. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:574–6. 10.1097/01.JTO.0000275341.39960.6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.