Abstract

Objectives

(1) To characterise variation in general practitioners’ (GPs’) accounts of communicating with men about prostate cancer screening using the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, (2) to characterise GPs’ reasons for communicating as they do and (3) to explain why and under what conditions GP communication approaches vary.

Study design and setting

A grounded theory study. We interviewed 69 GPs consulting in primary care practices in Australia (n=40) and the UK (n=29).

Results

GPs explained their communication practices in relation to their primary goals. In Australia, three different communication goals were reported: to encourage asymptomatic men to either have a PSA test, or not test, or alternatively, to support men to make their own decision. As well as having different primary goals, GPs aimed to provide different information (from comprehensive to strongly filtered) and to support men to develop different kinds of understanding, from population-level to ‘gist’ understanding. Taking into account these three dimensions (goals, information, understanding) and building on Entwistle et al’s Consider an Offer framework, we derived four overarching approaches to communication: Be screened, Do not be screened, Analyse and choose, and As you wish. We also describe ways in which situational and relational factors influenced GPs’ preferred communication approach.

Conclusion

GPs’ reported approach to communicating about prostate cancer screening varies according to three dimensions—their primary goal, information provision preference and understanding sought—and in response to specific practice situations. If GP communication about PSA screening is to become more standardised in Australia, it is likely that each of these dimensions will require attention in policy and practice support interventions.

Keywords: primary care, public health, qualitative research, prostate disease, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Qualitative methodology is well-suited to investigating complex multifaceted processes, like communicating about prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening from the perspective of clinicians, and preserves important contextual information relating to the process.

Data were from a large, rigorously derived sample of general practitioners (GPs) from different practice types and locations, and in two countries. The four approaches identified in this study may be applicable to a wide range of practice settings.

It is possible that those GPs who did not participate were in some way different to those who did (ie, that these data are subject to selection bias); however, the diversity in our respondents suggests that it is very unlikely that our sample was biased towards a particular view of PSA screening or corresponding communication style.

As this is a qualitative study, we cannot infer prevalence of the four reported approaches; the results of this study could be extended into quantitative survey research with whole populations of GPs to test prevalence.

Public and patient perspectives were not included in this study; additional qualitative research might explore their experiences of communicating with clinicians about prostate screening, to further inform policy and practice.

Introduction

Worldwide, many men undergo regular prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer risk in primary care. We will use PSA screening to refer to PSA testing in ostensibly healthy men who are not considered to be at high risk of prostate cancer for their age; this contrasts with PSA testing in men who have a diagnosis of prostate cancer or are experiencing acute symptoms that may suggest prostate disease. Although the value of the PSA test as a screening tool is scientifically contentious, the public perception of prostate screening is reportedly positive, including an inflated sense of the benefits and underestimation of the harms.1 Access to a PSA test is often via general practitioners (GPs). The large number of men screened in some countries, and the extent of public misperception and scientific contention, makes the communication between men and their GPs about prostate cancer screening especially important.

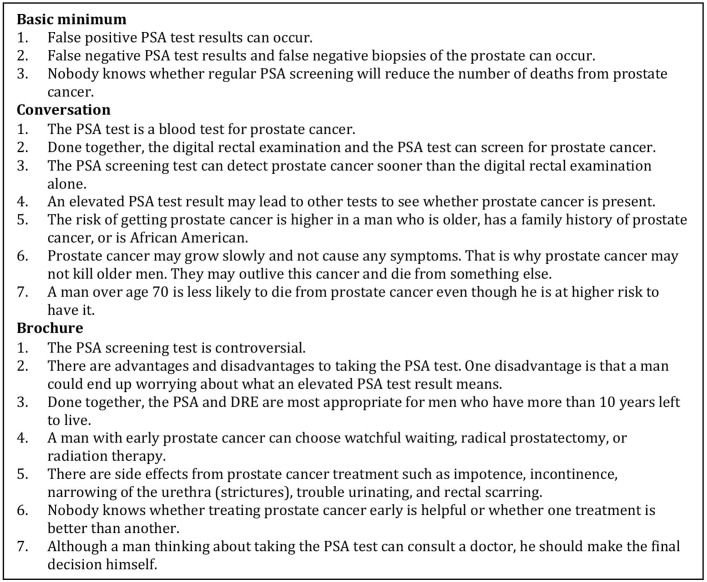

Communicating about screening is difficult. In-depth discussions about cancer screening can be complex and may involve multiple statistical concepts, such as test sensitivity and specificity, and absolute and relative risk reduction figures from trial-based evidence. Chan et al identified >20 specific informational items that experts and patients identified for inclusion in an ‘ideal’ discussion about prostate screening.2 The authors synthesised the items into a core set of key facts that clinicians should provide about PSA screening to their patients (figure 1, developed by KP); however, we note that even some of these items are contentious or inconsistent with the various national guidelines that we will discuss in the next section.

Figure 1.

Chan et al identified a core set of key facts that clinicians should include in an ‘ideal’ discussion about PSA screening.

Proposed communication standards for PSA screening discussions are reportedly challenging to implement in clinical practice.3–5 PSA tests are often ordered in the absence of any discussion; in the USA, men report being unaware of being screened,6 not being asked for their screening preferences and undergoing PSA testing without first discussing it with their doctor.7 Clinicians report offering screening without prior counselling.8 A survey of US physicians reported that 20% acknowledged ordering PSA without telling patients.9 This can be for various reasons.10 Volk et al surveyed US physicians and found that those physicians who reported ordering PSA tests without discussion were more likely to believe that patients wanted to be screened and that education is not needed. This was in contrast to those physicians who engaged patients in prescreening discussion because they believed patients should know about the lack of evidence supporting screening.11 Physician beliefs about the limitations of the scientific evidence for PSA screening, the questionable utility of the PSA test and ethical concerns regarding patient autonomy have also been identified as influencing the likelihood of discussions in US studies.10 12 Physician beliefs can shape the content of discussions; in a UK study, the strong personal views of clinicians against the value of PSA screening were reportedly clearly portrayed in their presentation of information about prostate cancer screening.13

In addition to this work on physician knowledge, values and attitudes, some researchers have studied patient and practice factors that may facilitate or preclude discussions about prostate cancer screening. For example, in one study US physicians were less likely to discuss screening if a patient had already made a decision about screening or was perceived to have limited ability to understand the information.10 Other studies have reported on factors affecting the quality of discussions, including a lack of time and the complexity of the topic.9

Clinicians have cited clinical guidelines and scientific evidence about prostate cancer screening as factors guiding their practice.13 However, this professional guidance varies widely, which may partly explain the observed variation in practice. Table 1 outlines the recommendations of key professional organisations in relation to communicating about prostate cancer screening, illustrating the main points of difference. ‘Informing’ men about the benefits and harms of PSA screening is universally recommended; and use of decision support tools is recommended by half of the professional organisations. Only 4 of the 10 guidelines advise whether GPs should raise the topic of PSA screening with men who do not ask about it in routine consultations. Medico-legal issues are referred to in only one, Australian, guideline. In practice, clinical guidelines may not always help GPs to decide how and what to communicate about PSA screening.14

Table 1.

Recommendations of professional organisations in terms of communicating about prostate screening

| Items included in recommendation and guidance | Professional organisation | |||||||||

| PCFA/CCA | NHMRC | RACGP | USANZ | NICE | NHS/PHE | USPSTF | ACS | NCI | AUA | |

| Is GP advised about whether to raise the topic with men if men do not raise it first? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Is a decision aid recommended? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Is a decision aid provided? | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Is IDM* recommended? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Is SDM† recommended? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Is guideline accompanied by a clinician information sheet?‡ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Is guideline accompanied by a patient information sheet?§ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Does guideline recommend clinician to share their own PSA screening decision? | ✓ | |||||||||

| Consider medico-legal responsibilities? | ✓ | |||||||||

*The patient is presented with all the information pertinent to making a decision and then assumes final authority for the decision.30

†The patient is provided with all the relevant information and works with the healthcare provider to reach a decision that reflects the health preference of the patient.30

‡A clinician information sheet is a fact sheet summarising the evidence of benefits, limitations and associated risks of prostate screening to help clinicians to accurately inform men.

§A patient information sheet is a fact sheet outlining the benefits, limitations and associated risks of having a PSA test for prostate cancer risk.

ACS, American Cancer Society; AUA, American Urological Association; GP, general practitioner; IDM, informed decision making; NCI, National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NHS/PHE, National Health Service/Public Health England; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; PCFA/CCA, Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia/Cancer Council Australia; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RACGP, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; SDM, shared decision making; USANZ, Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand; USPSTF, United States Preventive Services Task Force.

Entwistle et al characterised the two main ways that healthcare organisations communicate with the public about screening—Be screened and Analyse and choose—and proposed an alternative approach to communicating about screening, which they termed Consider an offer.15 The Consider an offer approach suggests healthcare providers should support people to assess an offer for screening, with a recognition that people may reasonably decline such offers. Consider an offer guides clinicians and patients to consider the source of screening recommendations and professional guidance. We return to the Consider an offer approach in the ‘Discussion’ section.

This study draws on a larger body of work investigating clinicians’ approaches to, and reasoning about, PSA screening in Australian and UK general practice. Despite similar levels of prostate cancer mortality, both PSA screening and prostate cancer incidence are lower in the UK than in Australia.16–19 Previous analyses from this study have illuminated systemic variation between the two jurisdictions, including in payment models, the history of PSA screening policy, screening culture and referral patterns.14 The authors have also published earlier findings from the empirical work about how clinicians manage the potential for overdiagnosis20 and their responses to uncertainty in relation to prostate screening.21 Table 2 summarises our previous findings regarding differences in PSA screening in the two jurisdictions. Note that prostate cancer screening is not recommended in either location.

Table 2.

Organisation and occurrence of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening in Australia and the UK

| Australia | UK | |

| For men asking about prostate screening |

|

|

| Screening frequency |

|

|

| Guidance for GPs |

|

|

| Preferred form of information provision |

|

|

| Appointment structure |

|

|

Summary of findings and details reported in Pickles et al 2016.

GP, general practitioner.

In the light of our prior findings on variation between the Australian and UK contexts, we set out to better understand GP communication practices in particular. The larger programme of study examined the role of values, ethics, context and evidence in cancer screening policy and practice. In this paper, we present an analysis of how GPs in Australia and the UK explain their approach to communication with men about prostate cancer screening. We asked the following research questions in respect of both settings:

How do GPs describe their communication with men about prostate cancer screening?

What are the reasons given by GPs for communicating with men as they do?

Why and under what conditions do GPs communication approaches vary?

Methods

GPs had an opportunity to discuss the study with KP prior to participation; all GPs provided informed written consent to participate and were compensated $A100 for their time. Participation was voluntary, participants could withdraw at any time and confidentiality was protected. All responses were anonymised before analysis and potentially identifying information removed.

Design

We applied the well-established, systematic qualitative research methodology of grounded theory.22 Grounded theory is a method of conducting qualitative research that focuses on creating conceptual frameworks or theories through building inductive analysis from the data. All study authors have been formally trained in qualitative research methods; SC has particular expertise in grounded theory methodology.

Participants and setting

We identified clinicians working in primary care practices as being in the best position to provide insight on our research questions, and most likely to face the question of PSA screening as part of their everyday practice. We purposively recruited a sample of GPs first in the Australian healthcare setting, and later in the UK (England, Scotland and Wales), as our study evolved. Sampling for the broader study was initially driven by existing quantitative evidence on characteristics of GPs, patients and practice contexts associated with higher or lower PSA screening rates. We aimed to recruit a set of GPs likely to have diverse practices. See Pickles et al 14 for a detailed description of the recruitment process.

In Australia, we advertised in newsletters and email lists of GP organisations, in mass and social media, medical journals, we phoned practice managers and via email and flyers distributed by rural GP organisations. In the UK, academic colleagues distributed an invitation through their professional networks, we advertised to members of the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), primary healthcare departments, university academic departments, and general practice and research via mail lists, and in organisational newsletters including the Society for Academic Primary Care and RCGP Scotland’s eBulletin. GPs were invited to contact KP if they were interested and willing to participate. An information sheet outlining the research project was emailed to all respondents. All GPs who expressed interest in participating were included.

Overall, 69 GPs participated in this study, 40 GPs in Australia and 29 GPs in the UK. 44/69 of the GPs were male. The GPs ranged in clinical experience, working from 1 to 40 years in general practice, and were located in both metropolitan (n=32/69) and regional/rural (n=37/69) clinics, with varied patient populations.

Data collection

The field work for the prostate cancer element of this study was conducted by KP, a public health researcher, as part of a PhD degree. KP had no immediate personal or professional experience with prostate cancer or PSA screening.

We generated data via in-depth semistructured interviews. An interview guide was prepared to provide general direction and an overview of potential question routes. The interview guide covered a broad range of topics, including GPs’ recent clinical encounters involving PSA screening decisions, communicating information about the PSA test to patients; screening pathways and overdiagnosis of prostate cancer. Example questions asked about communication included

Describe a recent consultation with an asymptomatic man involving the PSA test … Can you take me right back to the beginning and tell me as much as you can about the consultation. Who initiated the conversation about the PSA test?

Should men be informed about overdiagnosis, false positives before having a PSA test?

How well do you think men understand PSA screening?

The schedule was reviewed and modified between interviews based on the developing analysis to enrich the data available to answer our research questions. All GPs were asked to think back to their most recent consultation involving a discussion about PSA screening or to describe a typical consultation where the topic was raised.

Interviews took place between March 2013 and June 2014 (Australian GPs) and between September and December 2014 (UK GPs). We continued to interview GPs until we judged we had reached theoretical saturation; that is, the point at which gathering more data ceases to yield any further insights about the emerging grounded theory. All interviews were conducted by KP, primarily by telephone or Skype, and ranged in duration from 18 to 70 min. With GP permission, the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcribing service to produce data for analysis. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment; all participants will receive a written summary of the research findings on study completion.

Data coding and analysis

The analysis was led by KP, who coded the transcripts. A subset of transcripts was read and coded by three authors independently to ensure interpretive rigour. We coded to capture the range of variation in the GP-reported discussions about PSA screening and for conditions that could explain that variation. Codes were kept as similar to the data as possible to preserve context and to ensure that all concepts derived directly from the data. Codes were compared and discussed to inform the development of the central concepts in the study. KP wrote detailed memos during data collection and analysis which were reviewed and discussed by the authors in analysis meetings.

Results

We observed considerable diversity in the ways that GPs described their communication about prostate cancer screening. Although the majority of variation occurred among Australian GPs, we also report on data from the UK because this helps illuminate the contrasting complexity of the Australian data, including the role of local context.

We first explain how Australian GPs varied in their descriptions of their communication. We then consider important ways in which UK and Australian GPs were similar and different.

Australian GPs’ accounts of communicating with men about prostate cancer screening

Australian GPs’ accounts varied greatly in how they introduced conversations about PSA screening with men, how screening discussions were framed and their perceived informational obligations.

Screening men with little or no prior communication

A minority of interviewees reported ordering PSA tests for asymptomatic men with little or no prior communication with the patient. GPs were categorised as non-communicative if they reported (1) ordering PSA tests without explaining that to their patient, (2) ordering PSA tests at patient request with no further discussion or (3) explaining PSA screening only after a positive PSA test result. We encountered occasional practices from which asymptomatic men were mailed pathology forms for a PSA test via practice recall systems, bypassing a GP consultation and opportunity for discussion.

Several possible justifications were provided by non-communicative GPs:

Some GPs reasoned that because the information about PSA screening was ‘confusing’ ‘complicated’ and potentially contradictory, it should not be provided.

Some GPs said their role was to ensure that men could be screened if they wanted, ‘I see doctors purely as enablers, of what people want … If you don’t want to read about it [the test], then fine; I’ll just order one for you’ (AGP17).

Some GPs considered it ‘up to each patient to be informed appropriately’ (AGP14); if a man requested a PSA they would order a test assuming that man felt sufficiently informed from other sources.

Some GPs considered it unnecessary to provide information unless the man received a cancer diagnosis, ‘I don’t think they need all that information at the level of PSA testing. I think, that once you’ve got your cancer diagnosis, you can talk about what you want to do with that then’ (AGP26).

Some GPs did not appear to have a complete understanding of the epidemiological data, for example, ‘someone was saying that a certain number of people had to have radiation and surgery and have impotence and incontinence, for one person’s life to be saved. I mean—I don’t know how you get those figures’ (AGP2).

These were, however, minority views. We focus in what follows on the majority of GPs who did communicate with men in some way about PSA screening.

Communicating with men, with variation on three key dimensions

We identified three dimensions central to GP discussions with men about PSA screening:

The GPs’ primary communication goal. Some GPs had the goal of convincing the patient to screen, some had the goal of convincing the patient not to screen, and some had the goal of supporting decisions or facilitating patient choice.

The type of information the GP provided.

The type of patient understanding the GP sought to achieve.

It appeared that dimension 1 was dominant; GPs communicated in accordance with their preferred goal or outcome of the communication. In most cases, the GP’s positioning on dimensions 2 and 3 was grounded in whether the GP felt strongly that patients should be screened or not, and the degree to which they directed men towards that preference. Below we explain these three dimensions and GPs’ reasoning about them.

Dimension 1: GPs’ primary communication goal

Some GPs aimed to convince men either to agree to be screened or to agree not to be screened. These GPs had strong beliefs regarding whether or not PSA screening should occur routinely, and wanted patients to follow their advice, their ‘guide … down the path’ towards what they ‘thought was best’ (AGP29). GPs acknowledged ‘bias will creep into that’ (AGP29); ‘you can’t help yourself but … what you believe in is the way you push the consultation’ (AGP18). However, this approach was justified by beliefs that ‘… you can only do what you think is best for the patient’ (AGP29) and ‘a lot of people do want to be told what to do … doctors are their reference point’ (AGP31). GPs recognised that men sometimes chose not to take the advised pathway, for example, ‘there are times when it wouldn’t matter what you said to a patient they’re still determined to have the test’ (AGP18).

An alternative communication goal was to support men to make decisions about screening consistent with their own values and preferences. GPs with this goal aimed to facilitate an informed decision-making process and were determined to provide information to all men ‘to make up their own mind’ (AGP16), because ‘with the PSA test, I can’t so easily say to myself, well, it’s in your best interests so I don’t need to inform you properly’ (UKGP9). GPs with this goal reasoned that a man ‘should be empowered to know everything’ (UKGP28); ‘should have the right and want to be able to make that decision for themselves about whether they have the test or not’ (AGP5).

Dimension 2: GPs’ reported information provision

Because GPs had different goals in communicating, they provided different information, in both quality and quantity.

Some GPs claimed to provide men with ‘complete’ and ‘unbiased’ information because they considered it their ‘ethical obligation’ as a health professional to do so; the patient, in this view, had a ‘right’ to be fully informed, so GPs should ‘[put] all the information on the table’ (AGP31); ‘I’m very keen that people are well-informed about really what it means if they are to undertake a PSA rather than just simply agreeing to what their idea might be’ (UKGP23). This sometimes extended to teaching patients how to locate and interpret information for themselves. Informing patients was described by some GPs as serving a self-protective legal purpose, ‘I’ve informed the patient, the patient made his own decision, so he’s got to then accept the consequences’ (AGP19).

In contrast to GPs who sought to provide comprehensive information, other GPs filtered information to ‘actually tell them [patients] what counts the most’ (AGP4). Here GPs aimed to explain their own best judgement about the evidence, framing the evidence according to the GP’s opinion regarding the value of PSA screening. This often took the shape of a personal recommendation either to have a PSA test or not. One GP, for example, said ‘[patients] don’t have that knowledge so you sort of, give an explanation why it needs to be done’ (AGP35); another, in contrast, thought ‘my discussing it has probably been biased towards not getting it done’ (AGP16). Some GPs considered such advising to be best practice because information provision alone was not enough to help men decide what to do. For example, one GP who favoured PSA screening reasoned, ‘If they really don’t know what to do then [after receiving information], any doctor would be a fool not to say look, get it investigated because, the most stupid thing anyone could do is say oh don’t bother about it … that’s just a total recipe for disaster’ (AGP31).

Dimension 3: GPs’ reported ambitions for men’s understanding

All GPs aimed to support the development of patient understanding. However, there were two different conceptions of what constituted appropriate understanding of the information presented and available options:

Sometimes GPs aimed to assist men to develop detailed population-level understanding of the evidence. They wanted men to understand all aspects of the information provided and described checking understanding, identifying gaps in patient knowledge, and clarifying misunderstandings, because ‘I don’t think their pre-existing understanding of the test is very good at all in most cases’ (UKGP21). Some of these GPs reported feeling personally and professionally responsible for presenting the ‘right amount’ and ‘right level’ of information for individual patients, ‘[achieving understanding is] really the doctor’s job, and our skill in trying to explain all that complicated evidence, as best as we can’ (AGP19). Some GPs commented they hoped men understood the detail of the evidence, otherwise it indicated they as a GP had done a ‘bad job of explaining it’ (AGP6); however, they also explained ‘it’s a very difficult thing to formally confirm that they understand the implications of having the test done without kind of interrogating them’ (UKGP1).

Alternatively, GPs might aim for men to develop overall ‘gist’ understanding. GPs committed to ‘gist’ understanding were satisfied if their patient had a less complete grasp of the intricacies of the evidence base as long as they had an overall understanding of what the GP perceived to be core issues; ‘I feel like as long as they can understand that basic concept [in this instance, that PSA is not a perfect test] … then I feel like it’s okay to still do the testing, even if they don’t understand all the detail … I feel like that’s a reasonable level of understanding, I don’t feel like people need to have an absolutely thorough kind of understanding’ (AGP5). Those GPs who thought ‘gist’ understanding was acceptable thought it was reasonable for men to trust their doctor to advise them appropriately.

Relationship between the dimensions

When taking account of the three dimensions along which GPs varied, we identified four overarching approaches to communication: (1 and 2) Be screened and Do not be screened (GPs who guided men towards screening or not screening); (3) Analyse and choose (GPs who aimed to ensure men made their own independent, informed decision, based on a detailed population-level understanding); and (4) As you wish (GPs who simply facilitated the man’s stated preference to be screened or not screened). Two of these terms (Be screened and Analyse and choose) align with Entwistle et al’s characterisation of communication approaches,15 as outlined in the introduction. Each GP we interviewed had a general preference to employ one of these four approaches in their everyday communication about PSA screening. In table 3, we present an integrated illustration of the characteristics of each approach, ordered according to the three key dimensions evident in the GP accounts.

Table 3.

Four general practitioner (GP) approaches to communication about prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening in clinical interactions

|

Be screened interactions

GP’s primary goal:

|

Do not be screened interactions

GP’s primary goal:

|

Information provided by GP:

|

Information provided by GP:

|

Type of understanding that GP considered adequate:

|

Type of understanding that GP considered adequate:

|

|

Analyse and choose interactions

GP’s primary goal:

|

As you wish interactions

GP’s primary goal:

|

Information provided by GP:

|

Information provided by GP:

|

Type of understanding that GP considered adequate:

|

Type of understanding that GP considered adequate:

|

Be screened or Do not be screened interactions

If GPs had a strong preference that men should either be screened or avoid screening, they communicated in a directive way, oriented to encouraging the man either to screen or avoid screening respectively. This included offering personal judgement about the value—or harms—of PSA screening or framing the information they provided towards or away from screening. Some GPs gave a recommendation without offering men any further information. In Be screened and Do not be screened interactions, GPs considered it sufficient that men developed gist understanding of the information provided because they thought it was reasonable for men to trust their doctor to advise them appropriately. These GPs strongly believed either that men should be screened routinely, or that they should not be screened at all, and they wanted patients to follow their advice.

Analyse and choose interactions

If GPs aimed to support men to make their own decisions, consistent with the man’s personal preferences (ie, a patient-directed decision), then they were not directive in their communication. In these interactions, GPs aimed to provide a comprehensive and impartial summary of the best available evidence; their goal was to ensure that men developed a detailed population-level understanding of their options in order to make an informed decision. They saw this as a neutral, educative role. For some, this approach was protective against potential medico-legal threats. GPs using this approach may personally favour either screening or not screening, but their primary commitment was to support the man’s decision, regardless of their own professional beliefs about screening.

As you wish interactions

Sometimes GPs acted on patient wishes to be screened or not screened without questioning. In these interactions, GPs did not attempt to direct men in any particular direction, and often provided little information, ensuring that the man understood PSA screening was not a priority. In some cases, GPs perceived men to have already made a screening choice based on personal preference or gist understanding. These consultations typically involved men with an already-established screening preference, mostly for screening; the GP simply acted in line with the man’s instructions.

How GPs negotiate communicating within specific contexts

Many Australian GPs reported discussing PSA screening with men often, so had a prepared basic ‘spiel’; as one reported, ‘the PSA is such a common question that you get asked and you just have to have some idea in your head what you’re going to say when they come in’ (AGP18). This spiel could be tailored to specific contexts as necessary. GPs’ interviews indicated that they tended to have a preferred approach for most PSA interactions (to guide patient towards screening or not screening, to support men to make their own decision or to act in accordance with the man’s expressed preference) or that they had maintained a particular communication style over time. However, we identified 11 situational and relational factors (see table 4) that GPs described as temporarily shifting their usual or preferred communication goals and processes. These factors predominantly arose from specific circumstances of individual consultations. GPs described modifying their provision of information and/or advice, depending on the 11 factors described in table 4.

Table 4.

Effect of situational and relational factors on general practitioners’ (GPs’) approaches to communication in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening interactions, as described by GPs

| Situations that encouraged particular approaches to communication about PSA screening, as described by GPs | Examples of how GPs reported modifying their communication |

| Situational factors … pertaining to patient and/or GP | |

| Patient was from an older or younger age group (particularly <50 years or >75 years), or had comorbidities |

|

| Patient had a family history of prostate cancer |

|

| Patient requested to receive a PSA test or was perceived to be determined to have a test |

|

| Patient was interested in finding out more about screening |

|

| Situational factors … pertaining to service characteristics | |

| Rural location with limited access to urology services |

|

| Time available for the consultation (GP short of time) |

|

| Relational factors … pertaining to patient and/or GP | |

| GP made a judgement that the patient ‘starting point’ in terms of grasping the information was low and it would be difficult for them to understand PSA screening |

|

| Patient was perceived to be anxious, and so not receptive to information |

|

| GP made a judgement that the patient was ‘very switched on’ and had ‘done their homework’ |

|

| GP aware of patient history of screening (GP has screened patient in the past or has discussed screening with patient previously, GP knows patient’s screening preferences, or GP knows patient has been screened previously) |

|

| Relational factors … pertaining to service characteristics | |

| Patient was the usual patient of another GP, and patient asked for a PSA test |

|

GPs also shifted between the four communication approaches more readily when they were presented with complex cases; producing more fluid, responsive and sometimes ‘quite inconsistent’ (AGP16) conversations. Many GPs did have a primary goal when communicating (to encourage or discourage screening, or to support the man to make his own decisions) but these could change in different situations. Also, some men did not take the advised pathway—either towards screening or not screening, or some men preferred the GP to direct the decision, not wanting to engage with information or to make their own decision.

Comparison of communication approaches in Australia and the UK

UK GPs generally did not communicate about PSA screening unless men asked about it, so they often neither communicated about it as a screening test, nor ordered it. When men asked for a PSA test, information provision was central to consultations in the UK context, and most UK GPs commonly practised according to the Analyse and choose or Do not be screened approaches. Few UK GPs described adjusting their conversations about PSA screening with patients.

The reported consistency of PSA communication practices in the UK contrasted strongly with the significant variation reported in the Australian context (tables 3 and 4). The contextual factors considered in table 4 were uncommon in UK GPs’ accounts due to fewer men requesting and fewer GPs suggesting prostate screening. UK GPs mostly reported giving the same standard information leaflet to all men who expressed interest in PSA screening, regardless of their personal circumstances. Many GPs practising in Australia tended to filter information, and commonly practised according to the Be screened approach, but no UK GPs reported using this approach.

We identified different versions of the Do not be screened approach adopted by Australian and UK GPs. For the Australian GPs, this approach took the form of a personal recommendation against screening, directed by the GP and according to their personal—negative—perspective of PSA screening. For UK GPs, the Do not be screened approach also involved the GP recommending that the man should not be screened. However, UK GPs explained this as enactment of a collective standard of care recommended and issued by the UK National Health Service irrespective of their own personal preferences for or against screening.

Discussion

This analysis suggests that GPs’ primary communication goals are a central component of consultations about prostate screening. Four distinct communication approaches—Be screened, Do not be screened, Analyse and choose, and As you wish—were identifiable from GPs’ accounts of their preferred practice.

The terms Be screened and Analyse and choose align with Entwistle et al’s Consider an Offer framework. We identified two additional ways of communicating unique to our empirical data, which we labelled Do not be screened and As you wish. The need for inclusion of a Do not be screened element is likely a product of the Australian context where the PSA test is available and widely promoted for screening purposes in the media, despite the majority of relevant public health and health professional groups recommending against routine screening of asymptomatic men. This meant Australian GPs were regularly consulted by men expecting to be screened, and some reported feeling obligated to actively direct men away from wanting a PSA test for that purpose.

The As you wish category is also likely to be, in part, a reflection of the somewhat market-driven Australian healthcare system. As you wish interactions occurred when GPs’ believed men had already made up their minds about their preferred choice and could not be swayed by information presented by the GP. This led GPs to implement the man’s choice and order the test despite the lack of an evidence base to support that decision. There was no evidence of As you wish interactions in the UK data. As we previously reported,14 in the UK there is strong guidance to GPs to practice in a particular way. GPs are expected to steward limited National Health Service resources, and the PSA test is not publicly promoted to the same extent, limiting consumer expectations for screening. All of these are conceivable explanations for why As you wish interactions were less commonly reported in UK interviews.

The main issues raised by this analysis

The four variants raise important questions about patient-centred care, consumer demand and the role of the health professional. It is well established in the literature that both patients and clinicians are rarely entirely rational, and may not necessarily know what is in the patient’s best interest, particularly when faced with scientific uncertainty.23 24 Humans tend, for example, to become sensitised to worst-case scenarios and disregard objective risk probabilities; this makes us vulnerable to pursuing, recommending or accepting potentially harmful treatments.25 If this is so, an As you wish approach could mean patients are more exposed to increased harms, and that leaving patients to make decisions about their healthcare needs without professional guidance is potentially maleficent, or at least negligent. This problem is further complicated by the wide availability of possibly misleading information, provided by sources that have an interest in inflating perceptions of cancer risk. Some authors highlight that increased patient involvement in decision making has potential for negative social consequences such as increasing patient demand for unproven services.26 Cribb and Entwistle reasonably argue that in some circumstances it may be ethically legitimate for health professionals to question and even influence the preferences of patients for these reasons.27

Most current recommendations encourage GPs to discuss the benefits and harms of prostate cancer screening with patients. However, there may be considerable variation in what patients want and expect from GPs prior to making a decision about PSA screening. Degeling et al ran three community juries on the topic of how GPs should communicate about PSA screening. Juries heard extensive expert evidence about PSA screening, consent and general practice. Two juries of general citizens (ie, mixed gender and age) concluded that GPs should ensure men have enough knowledge to make their own decision. One jury of only men of PSA screening age concluded that men should be able to trust their GP (or a specialist) to provide just enough information at just the right time, expressed concern about the potential for information overload, and thought the degree of patient involvement depended on the patient.28 This suggests that citizens who are (atypically) well-informed about the benefits and harms of prostate cancer screening may take different views and have different expectations on how GPs should communicate about PSA screening. If this is the case, it may be appropriate for GPs to have at least a range of communication strategies available, to suit the needs of different patients. Men eligible for, or already receiving, PSA screening may well prefer for GPs to direct the decision (Be screened or Do not be screened approaches) to avoid uncertainty. However, men’s preferences are arguably an insufficient guide; other considerations, including clinical practice guidelines, medical law and clinical ethics requirements, are relevant to determining what GPs should do.

A large component of this analysis is about awareness of and sensitivity to context and the importance of interpersonal relations and their influence on communication practice (see table 4). Some of the GPs’ communication decisions, based on situational or individual factors, were easily justified because the situation presented was either clinically relevant (eg, family history, older age) or professionally justified (eg, low literate patient, patient request). While most guidelines advising on PSA screening suggest informed or shared decision making, they do not consider what may be a ‘best’ approach to situations involving the many local factors that GPs’ face in day-to-day practice, including relational factors, implicated in screening decisions (and the complexities of general practice). We identified a subtle web of relational issues that influenced GPs to move between communication options and particular types of decision pathways. These included managing colleague associations (what are GPs to do about patients who have come from a pro-screening GP to a GP who does not support PSA screening?), managing business, including patient lists (patient request, time pressures) and maintaining patient trust. These issues made the decision-making process particularly complicated, and in addition to vague guidance on such matters, perhaps account for why many GPs appeared to have multiple, dynamic approaches. Accounting for relational variables as identified in this study can facilitate nuanced assessment of the different types of support clinicians might offer people who may struggle with particular decisions29 and allows scope for professional expertise: the ‘art’ of medicine.

Implications for policy and practice

There are variable approaches to communication about PSA screening, some of which may be considered better than others. Guidance about communication—not just about the PSA test itself, but also about how best to facilitate the decision—may be useful; we suggest there is a need for further higher-level professional discussions about what the primary goals of GPs should be when communicating about PSA screening. Coming to an explicit agreement on what that purpose should be may assist in improving communication and providing clearer guidance for GPs working in the Australian context. For instance, one endpoint (that could be evaluated) may be that men can demonstrate they have a sense of their values in relation to the available options, to show evidence of rational, thoughtful and informed decision making.

Limitations

As this is a qualitative study, we cannot infer the prevalence of the reported approaches to communication; the results of this study could be extended into quantitative survey research with whole populations of GPs to test prevalence. It is also possible that those GPs who did not participate were in some way different to those who did (ie, that these data are subject to selection bias); however, the diversity in our respondents suggests that it is very unlikely that our sample was biased towards a particular view of PSA screening or corresponding communication style.

Conclusion

This empirical study produced evidence documenting varied approaches to communication. The reported consistency of PSA communication practices in the UK contrasted strongly with the significant variation reported in the Australian context. In the Australian setting, some flexibility in communication seems justified. Further, because of (1) the large number of men implicated, (2) the known harms of the screening process and (3) that PSA is not a routine screening programme, we argue that PSA screening is a particularly pressing case to necessitate dedicated effort to facilitate conversations that include but go beyond potential harms and benefits with men. This would include encouraging and enabling men who ask for screening to look carefully at why PSA screening is not recommended (to increase awareness of why a Do not be screened approach is justified). Assisting GPs to facilitate these conversations with patients should offer the advantage of supporting men’s autonomy and reducing harm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the general practitioners for their participation in this research. Thanks also to the reviewers of this manuscript and KP’s thesis examiners who helped to shape the final version of this paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: KP, SC and LR conceived the study and were involved in designing the study and developing the methods. SC and LR obtained funding and were CIs on the NHMRC-funded project grant; VE was an AI on the project. KP conducted the interviews, had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. KP drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the analysis and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: The work was supported by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant 1023197. SC reports grants from National Health and Medical Research Council Grant 1023197, 1032963; LR reports grant from National Health and Medical Research Council Grant 1023197 during the conduct of the study.

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: All study procedures were approved by the Cancer Institute NSW and the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (#15245).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C. Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:274–86. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chan EC, Sulmasy DP. What should men know about prostate-specific antigen screening before giving informed consent? Am J Med 1998;105:266–74. 10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00257-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, et al. . “Many miles to go …”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:14 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Han PK. Delivering a decision support intervention about PSA screening to patients outside of clinical encounters is ineffective in promoting informed decision-making. Evid Based Med 2015;20:139 10.1136/ebmed-2015-110196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Watson DB, Thomson RG, Murtagh MJ. Professional centred shared decision making: patient decision aids in practice in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:5 10.1186/1472-6963-8-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan EC, Vernon SW, Ahn C, et al. . Do men know that they have had a prostate-specific antigen test? Accuracy of self-reports of testing at 2 sites. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1336–8. 10.2105/AJPH.94.8.1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoffman RM, Couper MP, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. . Prostate cancer screening decisions: results from the National Survey of Medical Decisions (DECISIONS study). Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1611–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Han PKJ, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, et al. . Decision making in prostate-specific antigen screening. Am J Prev Med 2006;30:394–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dunn AS, Shridharani KV, Lou W, et al. . Physician-patient discussions of controversial cancer screening tests. Am J Prev Med 2001;20:130–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guerra CE, Jacobs SE, Holmes JH, et al. . Are physicians discussing prostate cancer screening with their patients and why or why not? A pilot study. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:901–7. 10.1007/s11606-007-0142-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Volk RJ, Linder SK, Kallen MA, et al. . Primary care physicians’ use of an informed decision-making process for prostate cancer screening. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:67–74. 10.1370/afm.1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Linder SK, Hawley ST, Cooper CP, et al. . Primary care physicians’ reported use of pre-screening discussions for prostate cancer screening: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:19 10.1186/1471-2296-10-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Purvis Cooper C, Merritt TL, Ross LE, et al. . To screen or not to screen, when clinical guidelines disagree: primary care physicians’ use of the PSA test. Prev Med 2004;38:182–91. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pickles K, Carter SM, Rychetnik L, et al. . Doctors’ perspectives on PSA testing illuminate established differences in prostate cancer screening rates between Australia and the UK: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011932 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Entwistle VA, Carter SM, Trevena L, et al. . Communicating about screening. BMJ 2008;337:a1591 10.1136/bmj.a1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Globocan 2012. Estimated cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence worldwide in 2012: International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organisation. 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx

- 17. Moss S, Melia J, Sutton J, et al. . Prostate-specific antigen testing rates and referral patterns from general practice data in England. Int J Clin Pract 2016;70:312–8. 10.1111/ijcp.12784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holden CA, McLachlan RI, Pitts M, et al. . Men in Australia Telephone Survey (MATeS): a national survey of the reproductive health and concerns of middle-aged and older Australian men. Lancet 2005;366:218–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66911-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Medicare Benefits Schedule Book Category 6: Australian Government Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pickles K, Carter SM, Rychetnik L. Doctors’ approaches to PSA testing and overdiagnosis in primary healthcare: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006367 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pickles K, Carter SM, Rychetnik L, et al. . General practitioners’ experiences of, and responses to, uncertainty in prostate cancer screening: insights from a qualitative study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153299 10.1371/journal.pone.0153299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ, et al. . Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA 2004;291:71–8. 10.1001/jama.291.1.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tymstra T. ‘At least we tried everything’: about binary thinking, anticipated decision regret, and the imperative character of medical technology. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2007;28:131 10.1080/01674820701288551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aronowitz RA. The converged experience of risk and disease. Milbank Q 2009;87:417–42. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00563.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Briss P, Rimer B, Reilley B, et al. . Promoting informed decisions about cancer screening in communities and healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med 2004;26:67–80. 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cribb A, Entwistle VA. Shared decision making: trade-offs between narrower and broader conceptions. Health Expect 2011;14:210–9. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00694.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Degeling C, Rychetnik L, Pickles K, et al. . “What should happen before asymptomatic men decide whether or not to have a PSA test?” A report on three community juries. Med J Aust 2015;203:335 10.5694/mja15.00164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Entwistle VA, Carter SM, Cribb A, et al. . Supporting patient autonomy: the importance of clinician-patient relationships. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:741–5. 10.1007/s11606-010-1292-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Volk RJ, Spann SJ. Decision-aids for prostate cancer screening. J Fam Pract 2000;49:425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.