Abstract

Objective

To analyse the completeness in GallRiks of the follow-up frequency in relation to the intraoperative and postoperative outcome.

Design

Population-based register study.

Setting

Data from the national Swedish Registry for Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), GallRiks.

Population

All cholecystectomies and ERCPs recorded in GallRiks between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2014.

Main outcome measures

Outcomes for intraprocedural as well as postprocedural adverse events between units with either a 30-day follow-up of ≥90% compared with those with a less frequent follow-up (<90%).

Results

Between 2006 and 2014, 162 212 cholecystectomies and ERCP procedures were registered in GallRiks. After the exclusion of non-index procedures and those with incomplete data 152 827 procedures remained for final analyses. In patients having a cholecystectomy, there were no differences regarding the adverse event rates, irrespective of the follow-up frequency. However, in the more complicated endoscopic ERCP procedures, the postoperative adverse event rates were significantly higher in those with a more frequent and complete 30-day follow-up (OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.76 to 2.11).

Conclusions

Differences in the follow-up frequency in registries affect the reported outcomes as exemplified by the complicated endoscopic ERCP procedures. A high and complete follow-up rate shall serve as an additional quality indicator for surgical registries.

Keywords: Adult Surgery, Hepatobiliary Surgery, Qualitative Research, Endoscopy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The prospectively collected data from over 90% of the registered cholecystectomies and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in nearly all Swedish hospitals is a major strength of this study.

Data reported by the medical professional performing the procedure always have the inherent risk of being subjected to certain bias. However, the 30-day follow-up data are collected by coordinators that have not met the patients.

Another limitation of this study is that it presents data from a period of 9 years (2006–2014) where the national coverage rate increased from 73% to 90%.

Introduction

National quality registry studies have been presented as a complement to randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Registry-based studies usually require less financial resources and enable data collection from large-scale patient cohorts without the unavoidable selection bias among those enrolled into clinical trials and most often carry valid statistical power. Databases with long-term follow-up open up for conduct of studies focusing on rare events harms and effects occurring late in the clinical course. There are several instances where registry-based studies have improved the management of patients, for example, in the treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome,1 the elimination of substandard orthopaedic prostheses from clinical use2 and the effects of different surgical approaches and suture materials on the outcome of hernia surgery.3 4 Accordingly registry studies can address clinical questions that due to statistical power issues, time and financial constraints would never have been studied under the design of a RCT such as the value of intraoperative cholangiography in preventing bile duct injury in association with gallstone surgery5 6 with data from the Swedish Registry for Gallstone Surgery and ERCP (GallRiks) or the question whether and why women with inguinal herniorrhaphies have a significantly higher reoperation rate compared with men (data from the Swedish Hernia Registry).7 Furthermore, in a RCT published in Lancet 2016, the outcome of closure of mesenteric defects in gastric bypass surgery was evaluated by analysing registry data from the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry.8

Thus, registry-based studies have a definite role in addressing many of the questions that arise in and have relevance for everyday clinical practice.

However, although population-based registry studies have high external validity, reflecting real-life data and the clinical routines as they are practised in the community at large, they are often hampered by the lack of uniform protocols and standardised routines for registering relevant data. This may skew the outcome since units, in which a limited awareness for quality of care is prevailing, may well report data with incomplete accuracy, leading to a risk for lower coverage concerning the registrations on adverse events by the participating units in the respective registers. Hence, such a heterogeneity in the validity of data may seriously limit the options for correct interpretations in respective outcome analyses.

Aims

To analyse the completeness in GallRiks of the follow-up frequency in relation to the intraoperative and postoperative outcome.

Methods

The Swedish National Registry for Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

The national Swedish Registry for Gallstone Surgery and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)9 (GallRiks) was established on 1 May 2005 as a registry for cholecystectomy and ERCP procedures.10 The aim of the registry is to obtain a comprehensive database of individuals subjected to these interventions, including information on patient demographics and the indications and outcomes of interventions. All data entering are online. The initial procedures, including information on perioperative complications, are usually registered by operating clinicians. At a 30-day follow-up, all medical records are reviewed for postprocedural adverse events and data are entered, usually by a local coordinator (nurse or a medical secretary).10 If a 30-day follow-up protocol of a cholecystectomy or ERCP is not complete or is missing, it is noted by the system and these procedures can easily be assessed when analysing the data. GallRiks data are compared with patients’ records on a regular basis by a dedicated independent validation team. A complete match between overall registry data and medical records has been reported in 98.2% of subjects with a 100% match for bile duct injury.11

Data extraction

Data on cholecystectomy and ERCP procedures performed between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2014 and entered into the GallRiks registry were assessed. Non-index procedures and procedures with incomplete data were excluded from the analysis. The complete 30-day follow-up frequency of cholecystectomy and ERCP procedures for individual units participating in the registry was calculated. We arbitrary chose the 90% limit for the 30-day complete follow-up in order to compare groups with sufficient number of procedures to reach enough statistical power to compare good follow-up (≥90%) with a less complete follow-up (<90%). Outcomes for perioperative and postoperative complications were studied.

Definitions

For the purpose of this paper, and in accordance with the descriptions in the GallRiks database, adverse events are defined and described per consensus agreement.

Cholecystectomy

Surgical removal of the gallbladder in patients with an indication for removing the organ including symptomatic gallstone disease, neoplasms and acalculous gallbladder conditions.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

An endoscopic technique for transpapillary access to the common bile duct and/or pancreatic duct including accessing the mentioned ducts through biliodigestive or pancreaticodigestive anastomoses, with diagnostic or therapeutic intent.

Index procedures

The first cholecystectomy and/or ERCP-procedure for each patient per in-hospital treatment period.

Intraprocedural adverse events for cholecystectomy

Bile duct injury, gut perforation, bleeding requiring intervention or other complications that adversely affected the operation.

Intraprocedural adverse events for ERCP

Bleeding, extravasation of contrast, perforation or any other reason for the ERCP being terminated prematurely.

Postprocedural adverse events

Complications during the 30-day follow-up period that require some form of medical or surgical intervention, including readmission or death.

Pancreatitis

Abdominal pain and an elevated amylase at least three times above normal at a time point >24 hours after terminating the procedure, as defined by Cotton et al.12

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP V.12.2.0 (SAS, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Comparisons of patient and procedure characteristics are presented in contingency tables, with pairwise differences analysed with a Pearson χ2 test. The influence of ≤90% follow-up on the risk of adverse events, pancreatitis and bleeding was analysed using multivariable logistic regression modelling. Each variable was tested in univariate and multivariate analyses for statistical significance, according to purposeful selection as described by Hosmer et al.13 In the multivariate analysis, the outcome was adjusted for sex, age (treated as a continuous variable in the models but presented dichotomised into < or ≥ 60 years(median)), comorbidity dichotomised into ASA 1–2 and ASA 3–5, acute or elective procedure and indication. The models were tested for multicollinearity and effect modification and were finally assessed for goodness of fit. The effects of analysed variables are presented as ORs for adverse events with 95% CIs.

Results

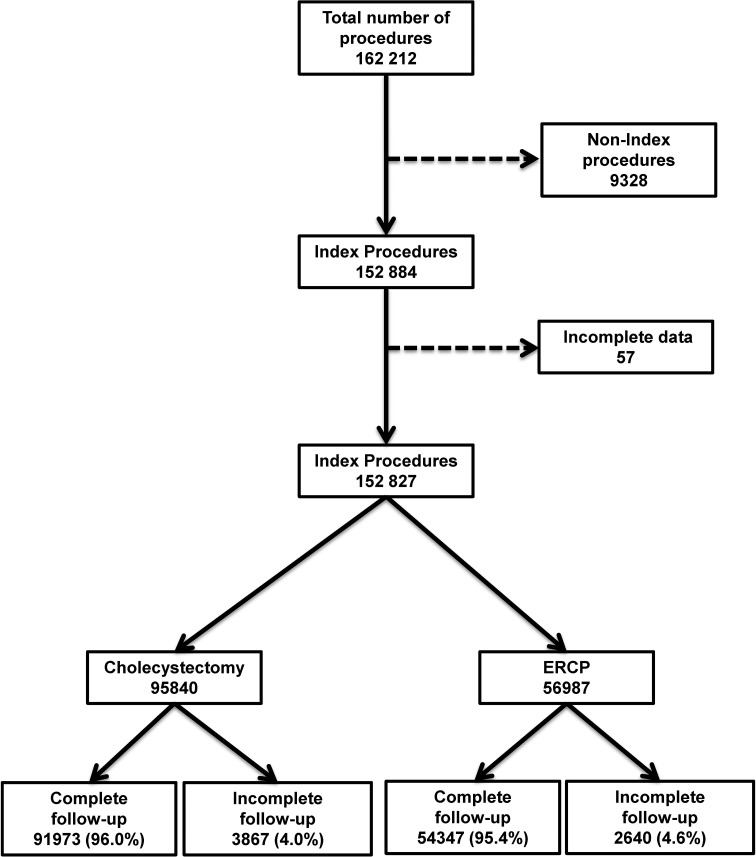

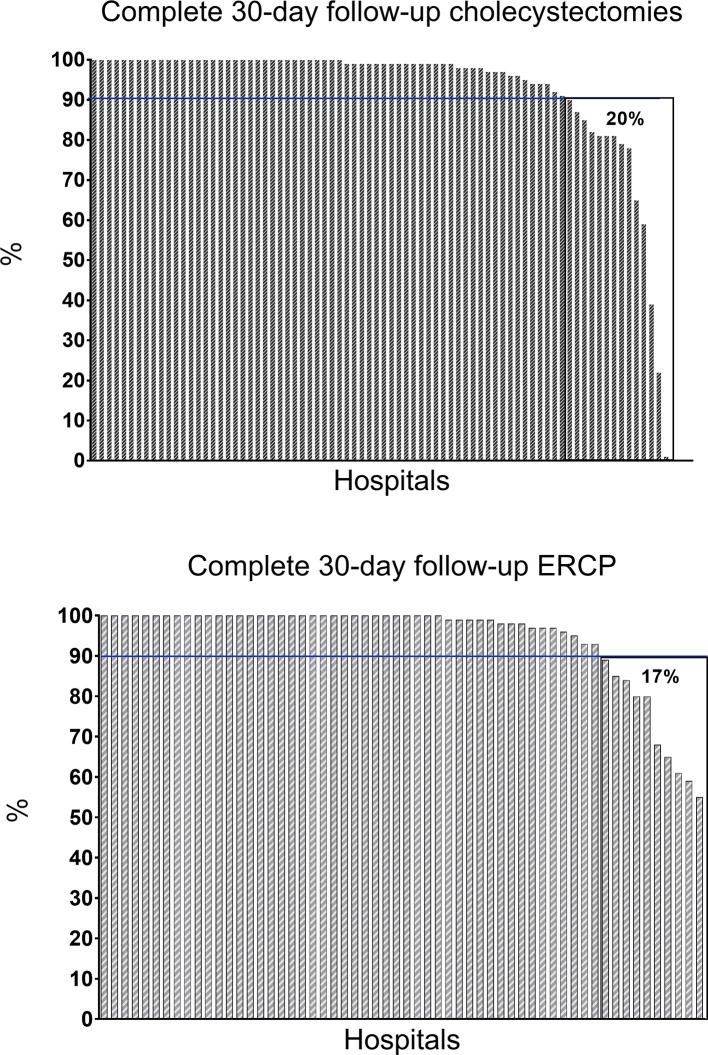

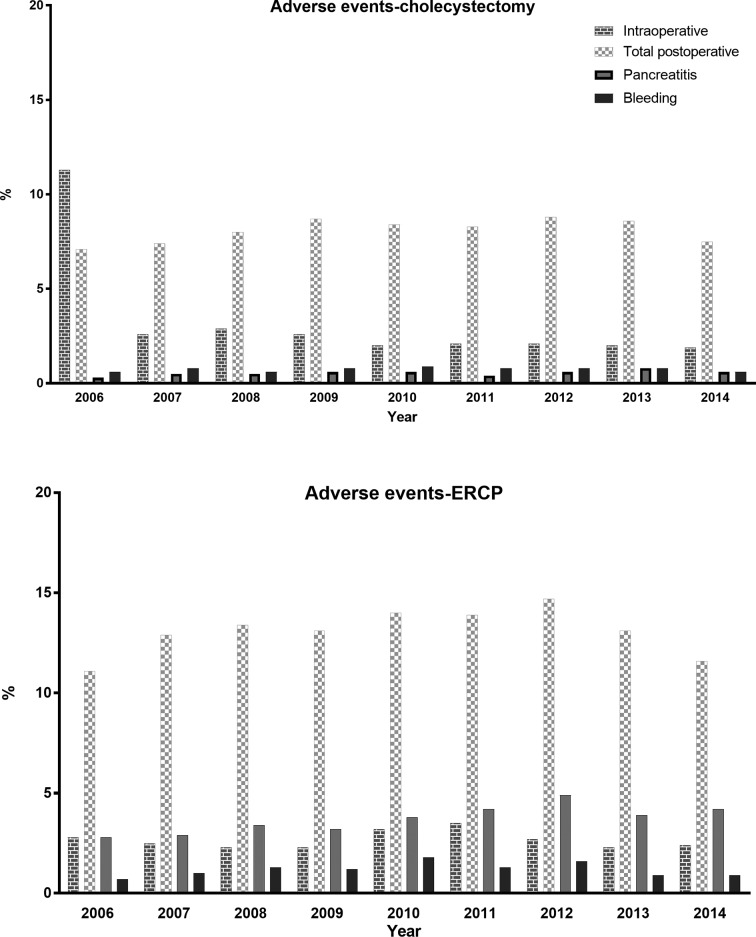

Between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2014, 162 212 cholecystectomies and ERCP procedures were registered in GallRiks. After the exclusion of 9328 non-index procedures and 57 procedures with incomplete data, 152 827 procedures remained for final analyses (95 840 cholecystectomies and 56987 ERCPs) (figure 1). In total, 96.0% of the cholecystectomies and 95.4% of the ERCP procedures had a complete 30-day follow-up. The distributions of a complete 30-day follow-up per hospital for cholecystectomies and ERCP procedures are depicted in figure 2. For the cholecystectomy group, 20% of the hospitals had a 30-day follow-up frequency of <90% compared with 17% for ERCPs (figure 2). The demographics, physical status assessment and urgency of intervention of included patients are given in table 1. Patients who were operated on with a cholecystectomy or underwent an ERCP in centres with incomplete follow-up were older and had a higher ASA score compared with those with a more complete 30-day follow-up. The adverse event rates for cholecystectomy and ERCP (intraoperative and total postoperative, with pancreatitis and bleeding showed separately) are given in figure 3. The overall total postoperative adverse event rate for cholecystectomies was significantly higher for the hospitals with a less complete 30-day follow-up. However, these differences disappeared when adjustments were made for sex, age, ASA-class and whether the operations were acute or scheduled (table 2).

Figure 1.

The procedures included in the analyses. ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Figure 2.

Complete 30-day follow-up frequencies following cholecystectomies and ERCP. The hospitals are ordered on the x-axis by level of completeness. ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Table 1.

Demographics, physical status assessment and urgency of interventions for the 152 827 patients included in the study

| ≥90 % | <90% | P value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| 30-day follow-up of cholecystectomies | |||

| Gender | |||

| Woman | 55 908 (67.3) | 8311 (65.1) | <0.0001 |

| Man | 27 159 (32.7) | 4462 (34.9) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≥60 | 26 442 (31.9) | 4462 (35.0) | <0.0001 |

| <60 | 56 461 (68.1) | 8290 (65.0) | |

| ASA | |||

| ASA 1–2 | 76 478 (92.1) | 11 124 (87.1) | <0.0001 |

| ASA ≥3 | 6589 (7.9) | 1649 (12.9) | |

| Acute/ Scheduled |

|||

| Acute | 24 237 (29.2) | 4433 (34.7) | <0.0001 |

| Scheduled | 58 830 (70.8) | 8340 (65.3) | |

| 30-day follow-up of ERCP | |||

| Gender | |||

| woman | 25 673 (53.0) | 4460 (52.0) | 0.0906 |

| Man | 22 743 (47.0) | 4111 (48.0) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≥60 | 35 532 (73.6) | 6724 (78.5) | <0.0001 |

| <60 | 12 767 (26.4) | 1843 (21.5) | |

| ASA | |||

| ASA 1–2 | 33 457 (69.1) | 4748 (55.4) | <0.0001 |

| ASA≥3 | 14 959 (30.9) | 3823 (44.6) | |

| Acute/ Scheduled |

|||

| Acute | 30 093 (62.2) | 5055 (59.0) | <0.0001 |

| Scheduled | 18 323 (37.8) | 3516 (41.0) | |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Figure 3.

Adverse event rates after cholecystectomies and ERCP. ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Table 2.

Adverse event rates, ORs and 95% CIs of hospitals with or without a 30-day follow-up frequency of cholecystectomies ≥90%

| Adverse events | P value | ||

| ≥90% | <90% | ||

| n=83 067 | n=12 773 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Intraoperative | 2548 (3.0) | 381 (3.0) | 0.8826 |

| Total postoperative | 6681 (8.0) | 1119 (8.8) | 0.0057 |

| Pancreatitis | 455 (0.6) | 66 (0.5) | 0.6570 |

| Bleeding | 629 (0.8) | 96 (0.8) | 0.9454 |

| ≥90% vs <90% 30 day follow-up Adjusted* | |||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Intraoperative | 0.93 | 0.84 to 1.04 | 0.2298 |

| Total postoperative | 0.98 | 0.91 to 1.05 | 0.5067 |

| Pancreatitis | 1.30 | 0.99 to 1.75 | 0.0606 |

| Bleeding | 0.97 | 0.78 to 1.21 | 0.7821 |

Figures in bold are statistically significant.

*Adjusted for sex, age, ASA class, acute interventions and indications.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

The overall total postoperative adverse event rate for ERCP during the study period was 13.2% and the pancreatitis frequency 3.8%. The incidence of these post-intervention adverse event rates was rather stable over the study period, except for pancreatitis where a small but significant increase was noted (figure 3). The reported risk of post procedural complications as well as pancreatitis and bleeding per se after ERCP was significantly increased in those hospitals with a more frequent and complete follow-up, both in absolute terms and when adjusted for confounders (table 3). The reported risk of postoperative adverse events, including post-ERCP pancreatitis, was nearly twice as high compared with the group with less complete follow-up. The risk of bleeding within the 30-day follow-up period was 38% higher in the group with a better follow-up. On the contrary, the risk of intraoperative adverse events was significantly reduced in the centres included in the ≥90% 30-day follow-up group (table 3). The overall 30-day mortality of cholecystectomies and ERCP in this study was 2.3%. However, since mortality figures are automatically transferred to the register from the Swedish Central Death Register, they are not affected by the local routines and management of the reporting hospitals.

Table 3.

Adverse event rates, ORs and 95% CIs of hospitals with or without a 30-day follow-up frequency of ERCPs ≥90%

| Adverse events | P value | ||

| ≥90% | <90% | ||

| n=48 416 | n=8571 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Intraoperative | 1267 (2.6) | 252 (2.9) | 0.0868 |

| Total postoperative | 6821 (14.1) | 689 (8.0) | <0.0001 |

| Pancreatitis | 1978 (4.1) | 178 (2.1) | <0.0001 |

| Bleeding | 591 (1.2) | 76 (0.9) | 0.0081 |

| Adverse events | |||

| ≥90% vs <90% 30 day follow-up Adjusted * | |||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Intraoperative | 0.76 | 0.66 to 0.87 | 0.0002 |

| Total postoperative | 1.92 | 1.76 to 2.11 | <0.0001 |

| Pancreatitis | 2.04 | 1.72 to 2.43 | <0.0001 |

| Bleeding | 1.38 | 1.08 to 1.79 | 0.0100 |

Figures in bold are statistically significant.

*Adjusted for sex, age, ASA class, acute interventions and indications.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Discussion

The results of this study, analysing data from the nation-wide Swedish Registry for Gallstone Surgery and ERCP (GallRiks), emphasise the importance of considering a thorough follow-up as an important confounder when analysing the outcome of registry-based studies. Furthermore, differences in the follow-up frequency seemed to have a greater impact as a confounder in the technically more complicated procedures like ERCP where complications like pancreatitis and cholangitis usually are detected postoperatively in contrast to cholecystectomies where the adverse events and complications usually are detected intraoperatively. Thus, since the ERCP procedures to a higher extent are marred by postoperative complications, the demands for a thorough and logistically well-designed follow-up organisation with adequate resources are mandatory.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The prospectively collected data in GallRiks from >90% of the registered procedures in nearly all Swedish hospitals is a major strength of this study. The data registered in GallRiks have also been verified to have a high validity of >98%.11 Another strength is that this report includes data from University Hospitals, County Hospitals, District Hospitals and private units as well. The quality of data has been a concern already from the start of the registry and is guaranteed by continuous quality controls of the data validity. However, due to financial and time constraints, this prospective and integrated part of the registry has to be limited to approximately 50 randomly selected, cross-matches between patient records and GallRiks registrations at each hospital completed every third year.

Data reported by the medical professionals performing the respective intervention or data assessment always have the inherent risk of being subjected to certain bias. When analysing the results of quality registry data, factors like coverage of the relevant population by the registry data as well as the follow-up rate have to be taken into consideration. Another limitation of this study is that it presents data from a period of 9 years (2006–2014) where the national coverage increased from 73% to 90%. However, there is no systematic reason why the proportion of those with incomplete versus complete follow-up shall depend on the coverage rate as such. It must also be emphasised that, although we found significant differences between units with a high (≥90%) and units with <90% complete follow-up, the overall completeness must be considered excellent since only 4.0% of the cholecystectomies and 4.6% of the ERCPs have an incomplete follow-up. Nevertheless, the absence of uniform study protocols makes it impossible to fully guarantee overall quality of data in population-based registers. Even if these data are considered to have high external validity, the population-based registers may still produce some skewness of the data. The care for accuracy of reporting, and providing healthcare of high quality, may result in a positive correlation between self-reported adverse outcome and completeness of data. On the other hand, centres, where the quality of care is poorer, may also have insufficient routines for scrutinising treatment outcome. The only way of avoiding this is a meticulous validation of all registered data, preferably with careful selective assessment of data from units with low coverage as well as to provide continuous education and support from the registry to the participating units with less complete follow-up routines.

Comparison with other studies

RCTs are considered one of the cornerstones of modern, evidence-based medical science. It is regarded as the most accurate method to answer key clinical questions and to offer the highest levels of evidence that can be translated into the strongest treatment recommendations.14 However, RCTs are also associated with definite drawbacks and logistic challenges.15 16 In addition, in the case of industry-funded research, and particularly so when study data are owned by the sponsoring body, study results that might have negative economic implications are sometimes withheld from publication, leading to publication bias.17 Furthermore, the number of included patients necessary for creating sufficient power for testing of hypotheses in RCTs may preclude the completion of trials within reasonable time limits.18 Moreover, treatment methods that in RCTs originating from large academic institutions from which excellent results are reported cannot always be repeated by and implemented in smaller and more resource-challenged facilities. It has also been shown that the outcome for patients excluded from randomisation often differs significantly from those enrolled in the randomised trial cohort.19 Thus, registry-based studies can and shall be looked on as offering a complement to RCTs data, since they can more closely mirror the effect of a certain treatment-intervention in the entire population, given that good coverage is prevailing.

Several national quality registries have reported good coverage which is a prerequisite for a well-functioning quality registry, particularly so for cancer registries and in the paediatric population.20 21 As for Sweden, there are 53 national quality registries that report their coverage to the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.22 Of these 53 registries, 19 cover specific interventional procedures, for example, gynaecological operations, hip-replacement, hernia surgery, and cholecystectomy, to mention a few. The national coverage of these registries varies from 46% to 98%. In fact, some of these registries have a better coverage than the Swedish National Patient Registry (NPR) because many of the procedures are done by private hospitals that do not report to NPR as diligently as the government-funded hospitals.

Besides having good coverage, it is of vital importance for quality registries to contain valid data. Dedicated validation processes should be in place for assessing and reporting the correctness of the included data at regular intervals. The issue of a complete follow-up is especially challenging in registries with focus on the management of benign diseases, since these procedures do not have the same rigorous demands of a compulsory follow-up as those for malignant conditions.

The impact of the level of completeness of the follow-up for the validity of reported outcomes in registries covering benign conditions, has not been previously probed and elucidated in the literature. A survey by Rystedt et al,11 based on the validation of GallRiks, showed a high completeness and correctness of entered data with an overall correctness of data of 98.2% and 100% for bile duct injuries. However, in this publication the completeness of the 30-day follow-up was not specifically addressed. There may also be a relative preponderance of smaller units among those with low completeness. It is often more difficult to organise standardised routines when the volumes are low. This could explain the relatively high completeness on the national level despite the very low completeness at a few hospitals.

The compelling finding of this paper is that the reported incidence of postoperative adverse events after ERCP is significantly lower in hospitals with an incomplete 30-day follow-up frequency (<90%) as compared with those with a more complete follow-up (≥90%). Although these results could mirror true outcomes, it is more likely to be the result of failure to report some of the adverse events by the hospitals with a less stringent documentation system for follow-up and/or a lack of coordinators. The coordinator has the liability, together with the GallRiks responsible surgeon, that the patient’s data are registered and monitored. A contract is signed with the head of the department that ≥90% follow-up in GallRiks should be done. The agreement is broken at the units that have <90% 30-day follow-up.

These assumptions of less stringent reporting are supported by the finding that the reported incidence of intraoperative adverse events is significantly higher in the group with ≥90% 30-day follow-up, implying that hospitals with an immaculate and accurate information accrual system also follow-up patients more diligently and report adverse events to a higher degree. This discrepancy, where a less frequent 30-day follow-up significantly affected the reported outcome in ERCP but not in cholecystectomy could imply that the effect of a complete 30-day follow-up is more pronounced in procedures with a higher complication profile, since ERCPs have a more congested postoperative complication profile compared with cholecystectomies.

Conclusions and implications

Our findings may have significant general implications on how we shall interpret outcome data from registry studies. Differences in the follow-up rate seemed to significantly affect the reported outcome. The findings suggest that the validation process has to include the completeness of follow-up. Differences in the follow-up frequency in registries affect the reported outcomes as exemplified by the complicated endoscopic ERCP procedures. The study emphasises the importance of complete follow-up, since this variable may well act as a quality indicator for the respective registry.

Future research

Future research should focus on how the degree of complete follow-up in quality registers can correlate to more objectively and not self-reported quality indicators.

Transparency

The first author (LE) confirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LE: conceived the study, created the study design, participated in the statistical analysis, analysed the data and drafted and revised the paper. MB: participated in the analysis and interpretation of data, and revised the paper. GS: participated in the statistical analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted and revised the paper. EJ: interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. BH: conceived the study and reviewed the manuscript. LL: interpreted data and reviewed the manuscript. JÖ: conceived the study, created the study design and drafted and revised the paper. All authors: have approved of the final draft submitted.

Funding: This study was made possible by a grant from the Umeå University ALF research funding. The funding body had no role in the study. The GallRiks Registry is funded by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Regional Research Ethics Committee at KarolinskaInstitutet, Stockholm, Sweden, approved the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional unpublished data from this study. The data in this study are taken from Swedish registry of Cholecystectomy and ERCP (GallRiks) and are available via the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1. Damman P, Jernberg T, Lindahl B, et al. Invasive strategies and outcomes for non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a twelve-year experience from SWEDEHEART. EuroIntervention 2016;12:1108–16. 10.4244/EIJY15M11_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Graves SE. The value of arthroplasty registry data. Acta Orthop 2010;81:8–9. 10.3109/17453671003667184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dahlstrand U, Wollert S, Nordin P, et al. Emergency femoral hernia repair: a study based on a national register. Ann Surg 2009;249:672–6. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819ed943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Novik B, Nordin P, Skullman S, et al. More recurrences after hernia mesh fixation with short-term absorbable sutures: a registry study of 82 015 Lichtenstein repairs. Arch Surg 2011;146:12–17. 10.1001/archsurg.2010.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Törnqvist B, Strömberg C, Persson G, et al. Effect of intended intraoperative cholangiography and early detection of bile duct injury on survival after cholecystectomy: population based cohort study. BMJ 2012;345:e6457 10.1136/bmj.e6457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Törnqvist B, Strömberg C, Akre O, et al. Selective intraoperative cholangiography and risk of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2015;102:952–8. 10.1002/bjs.9832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bay-Nielsen M, Kehlet H. Inguinal herniorrhaphy in women. Hernia 2006;10:30–3. 10.1007/s10029-005-0029-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stenberg E, Szabo E, Ågren G, et al. Closure of mesenteric defects in laparoscopic gastric bypass: a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trial. Lancet 2016;387:1397–404. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01126-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gallriks. 2017. www.gallriks.se

- 10. Enochsson L, Thulin A, Osterberg J, et al. The Swedish Registry of Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (GallRiks): a nationwide registry for quality assurance of gallstone surgery. JAMA Surg 2013;148:471–8. 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rystedt J, Montgomery A, Persson G. Completeness and correctness of cholecystectomy data in a national register–GallRiks. Scand J Surg 2014;103:237–44. 10.1177/1457496914523412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc 1991;37:383–93. 10.1016/S0016-5107(91)70740-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hosmer DW, Taber S, Lemeshow S. The importance of assessing the fit of logistic regression models: a case study. Am J Public Health 1991;81:1630–5. 10.2105/AJPH.81.12.1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carter AJ, Nguyen CN. A comparison of cancer burden and research spending reveals discrepancies in the distribution of research funding. BMC Public Health 2012;12:526 10.1186/1471-2458-12-526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J, et al. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:MR000033 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doucet M, Sismondo S. Evaluating solutions to sponsorship bias. J Med Ethics 2008;34:627–30. 10.1136/jme.2007.022467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van den Broek MA, van Dam RM, Malagó M, et al. Feasibility of randomized controlled trials in liver surgery using surgery-related mortality or morbidity as endpoint. Br J Surg 2009;96:1005–14. 10.1002/bjs.6663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ros A, Carlsson P, Rahmqvist M, et al. Non-randomised patients in a cholecystectomy trial: characteristics, procedures, and outcomes. BMC Surg 2006;6:17 10.1186/1471-2482-6-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larsen IK, Småstuen M, Johannesen TB, et al. Data quality at the Cancer Registry of Norway: an overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1218–31. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steliarova-Foucher E, Kaatsch P, Lacour B, et al. Quality, comparability and methods of analysis of data on childhood cancer in Europe (1978-1997): report from the Automated Childhood Cancer Information System project. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:1915–51. 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. 2017. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/english/compare

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.