Abstract

Introduction

Acute chest pain represents a major healthcare burden in emergency departments (ED) throughout the world. Among these patients, rapidly determining whether an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is evolving remains difficult. In China, there are limited data correlating the baseline characteristics, evaluation and management of ED patients with acute chest pain and ACS-related symptoms with clinical outcomes. Nor has there been an evaluation of outcomes at different levels of hospitals. The Evaluation and Management of Patients with Acute ChesT pain in China (EMPACT) study will address this evidence gap through a regional representative prospective registry.

Methods and analysis

Twenty-two public hospitals with ED in Shandong province have been selected based on a stratified random sampling approach. A total of 10 000 patients with acute chest pain or suspected ACS presenting to the ED will be consecutively enrolled from January 2016 to September 2017. Episodes of care will be evaluated for key performance measures such as the time to first ECG, receipt of troponin testing, receipt of reperfusion therapy for ST segment elevation ACS and provision of angiography for troponin-positive patients. All patients will be assessed for the composite endpoint of adjudicated major adverse cardiac events in 30 days after presentation, including death from all causes, non-fatal myocardial infarction, urgent revascularisation, stroke, cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock. The secondary outcomes include revisit to ED and rehospitalisation within 30 days.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained at all participating centres. The registry is the first attempt to comprehensively evaluate the current emergency care of acute chest pain from a regional representative sample in China. Findings will allow new opportunities to facilitate the clinical quality improvements and ultimately reduce the mortality in patients with acute chest pain and suspected ACS.

Trial registration number

NCT02536677; Pre-results.

Keywords: Acute Chest Pain, Evaluation, Management, Outcomes, Emergency Department

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Evaluation and Management of Patients with Acute ChesT pain in China (EMPACT) is the first regionally representative registry using stratified random sampling to assess the care and outcome of patients with chest pain presenting to the emergency department (ED).

Eligible patients will be enrolled consecutively where possible (ie, 24 hours per day, 7 days per week) for 12 months.

The ultimate diagnoses of patients admitted to hospital and all major adverse cardiac events (MACE) will be independently adjudicated by clinical events committee.

EMPACT will comprehensively correlate hospital performance measures for evaluation and treatment of chest pain and suspected patients with ACS with 30-day clinical outcomes, providing valuable targets for emergency care quality improvements with potential impacts on China and other developing countries.

Current medical insurance policy and medical records practices may lead to an underestimation of the ED function of patient triage.

Introduction

Acute chest pain is one of most common causes for visits to emergency department (ED) throughout the world. It represents 5.2% of all ED visits in the USA and 6% in England and Wales.1 2 Due to the rapid socioeconomic development and the far-reaching healthcare reform policies, Chinese hospitals have been confronted with a 170% increase in the visits to the ED during the past decade3–5 and the proportion of acute chest pain is approximately 4.7%.6 Therefore, visits of patients with chest pain to the ED have increased enormously, and the evaluation and management of these patients has led to a huge burden on the Chinese emergency care system.

The cause of chest pain is extremely heterogeneous with a wide spectrum of conditions ranging from lethal diseases to minor acute problems.7–10 Among the differential diagnoses of chest pain, rapidly determining whether a patient has an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or not, is challenging. In North America and Europe, the inappropriate discharge of patients with ACS from ED is estimated to be between 2% and 5.3%,11–14 and among these patients, mortality is nearly two times greater as compared with admitted patients.11 These rates are high when considering the reported ‘acceptable’ 30-day missed death or myocardial infarction (MI) rate of less than 1%.15 On the other hand, 60%–80% acute chest pain are not due to ACS and 50%–67.2% have non-cardiac conditions,7 9 16 which do not require unnecessary diagnostic tests and prolonged observation. Therefore, it is challenging for ED physicians to arrive at the right balance when weighing risks and using resources to identify an ACS.

Several authoritative guidelines and statements have recommended assessment strategies for ED patients with undifferentiated chest pain to determine the likelihood of ACS and the risk level for clinical adverse outcomes.7 8 10 16–18 Some recommendations highlight the importance of clinical algorithms for the initial evaluation and diagnostic testing to determine those who require immediate management versus those who are suitable for early discharge. Nevertheless, to date, there are limited data evaluating clinical performance measures and their correlation with outcomes among Chinese ED patients with acute chest pain and ACS-related symptoms. Furthermore, assessing the correlation between performance measures and outcome across different levels of hospitals may be valuable for establishing the validity of these measures in clinical policy.

Well-designed observational studies are critical to assess the practice patterns and to understand the relationships between management and outcome for patients presenting to the ED with acute chest pain and ACS-related symptoms.2 9 14 19–23 In China, clinical research is an emerging science.24 For admitted patients, evaluation of hospital level measures of cardiovascular care have been performed in several clinical studies.25–28 However, for ED patients, this kind of systematic information is deficient, which seriously hinders the improvements of emergency healthcare and outcomes in this subgroup of patients.

The Evaluation and Management of Patients with Acute ChesT pain in China (EMPACT) is a multicentre prospective registry, designed to establish a regional research network and develop a sophisticated clinical database. This study will collect information in real time from a regional representative sample of public hospitals and describe the clinical characteristics, evaluation, management and outcomes of ED patients experiencing acute chest pain and ACS-related symptoms. This quality assurance initiative across different hospital strata will provide the first-hand knowledge to facilitate the emergency care quality improvement, while providing valuable experience for further studies focusing on ED patients with acute chest pain in China. Furthermore, the results from this large low/middle-income country with approximately one-fifth of the world’s population may have global potential impact.

Methods and analysis

Overview of the EMPACT

EMPACT has been designed to consecutively enrol patients presenting to the ED with acute chest pain or with suspicion of ACS across a representative sample of public hospitals in Shandong province. The enrolment period will be for 12 months. The registry is to describe the baseline clinical profile, initial evaluation, further diagnostic testing, treatment and 30-day outcomes. The primary hypothesis is that there is a difference in the incidence of 30-day major adverse clinical events (MACE) in acute chest pain and suspected patients with ACS presenting to ED in rural hospitals compared with that in urban hospitals. Thus, the primary aim is to correlate hospital performance measures for evaluation and treatment with 30-day outcomes in ED patients with acute chest pain and suspected ACS.

Site selection

As China’s second most populous province, Shandong administers 17 prefectural-level cities and 84 counties and county-level cities. From the official view, the former 17 cities are considered as urban and the latter as rural.5 Hospitals in China are organised as three grades according to their capacity and ability to provide medical services. Grade I hospitals contain less than 100 beds and serve as a community hospital. Grade II hospitals have 100–500 beds and provide comprehensive health services and medical education for several communities. Grade III hospitals are the comprehensive or general hospitals at the city, provincial or national level with a bed capacity exceeding 500.29 In addition, hospitals are classified as general hospitals, hospitals of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and specialised hospitals.5

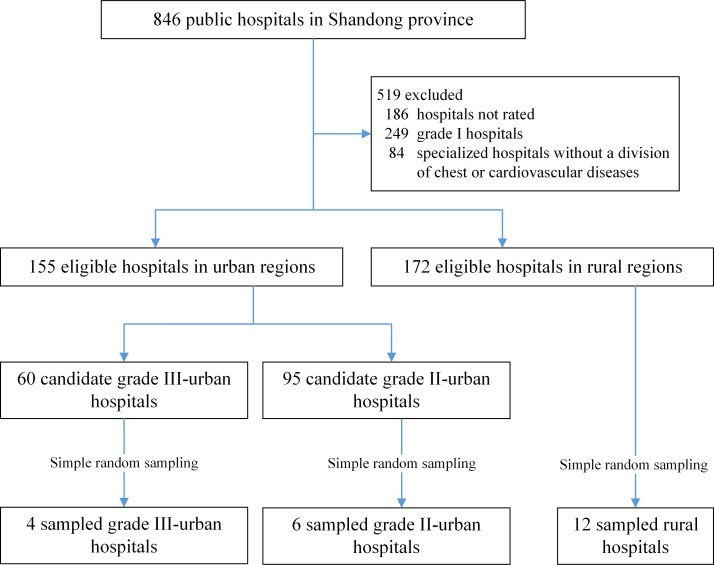

We used a stratified random sampling design to generate a Shandong province representative sample of public hospitals with independent ED, opening 24 hours per day, 7 days per week that are capable of treating patients with acute chest pain. A total of 846 public hospitals were assessed and 519 hospitals were excluded, including 186 hospitals that did not have a rating, 249 grade I hospitals and 84 specialised hospitals which did not have a division of chest or cardiovascular diseases. We stratified the eligible hospitals into four strata: grade II-rural, grade III-rural, grade II-urban and grade III-urban. Because of the similar volume of chest pain visits estimated from our initial investigation, the rural grade III stratum was merged with the rural grade II stratum. Then, we randomly selected 1/15 of all hospitals from each stratum to generate a total estimated sample size of 10 000 patients. Twenty-two hospitals were randomly selected, including 12 rural hospitals, 6 grade II and 4 grade III urban hospitals (figure 1). One grade II urban hospital refused to participate. As a coordinating centre, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University was included in the study without participating in the sampling methodology. Hence, a total of 22 hospitals were included.

Figure 1.

Site selection flow chart.

Among the participating sites, 18 are general hospitals and 4 are TCM. There are three teaching hospitals. Most of the participating hospitals have a catheterisation centre (16/22) and more than half (14/22) of them are equipped with a cardiac care unit. The median number of hospital beds (IQR) is 898 (500–1600) and the median number of ED annual visits (IQR) is 33 768 (13 017–54 550). Twelve hospitals use the computer system to collect clinical data in ED, whereas the other hospitals use handwritten medical records (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitals that participated in EMPACT

| Variables | Number |

| Geographic region | |

| Rural | 12 |

| Urban | 10 |

| Hospital grade | |

| Grade II | 15 |

| Grade III | 7 |

| Hospital type | |

| General hospital | 18 |

| TCM | 4 |

| Teaching hospital | |

| Yes | 3 |

| No | 19 |

| Hospital features | |

| Beds, median (25 %, 75 %) | 898 (500, 1600) |

| CCU | |

| Yes | 14 |

| No | 8 |

| Catheterisation centre | |

| Yes | 16 |

| No | 6 |

| ED features | |

| Annual visits, median (25%, 75 %) | 33 768 (13 017, 54 550) |

| Physician in ED 24/7 | |

| Yes | 22 |

| Computer system collecting clinical data | |

| Yes | 12 |

| No | 10 |

CCU, cardiac care unit; ED, emergency department; EMPACT, the Evaluation and Management of Patients with Acute ChesT pain in China; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine.

Patient enrolment

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in box. Informed consent for inclusion and follow-up contact will be obtained from all patients at enrolment. A total of 10 000 patients are anticipated to be consecutively enrolled from the participating hospitals. The beginning dates of enrolment for each hospital were distributed from January to September 2016 among the 22 centres. For each hospital, the enrolment duration will be for 12 months.

Box. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Eighteen years and older.

Presenting to the emergency department (ED).

With acute chest pain or suspected acute coronary syndrome.

Symptoms occurring within 24 hours.

Informed consent from patient or next of kin.

Exclusion criteria

Chest pain caused by trauma.

Persisting or recurrent chest pain caused by rheumatic diseases or cancer.

Transferred from another grade II or grade III hospital.

Presenting to the ED again within 30 days after initial enrolment.

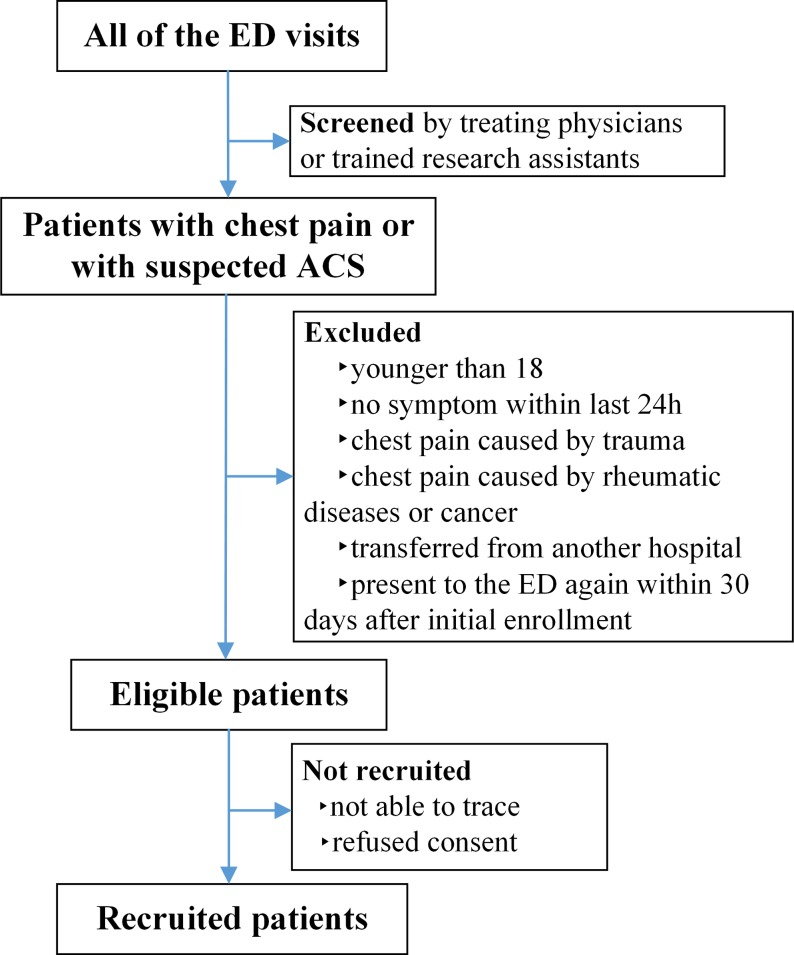

Subjects with acute chest pain and ACS-related syndromes will be directly identified by trained research assistants and enrolled when they present to the ED. Patients suspected to be experiencing ACS will be determined by treating physicians according to their clinical judgement. Research assistants will screen all the ED visits on a daily basis to capture the eligible patients consecutively where possible. A log of enrolment status, documenting whether the patient will be recruited, excluded, not recruited and the reasons for exclusion will be completed for all potentially eligible patients (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Consecutive enrolment flowchart. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ED, emergency department.

Data collection and quality control

Data collection will be prospectively conducted on a standardised case report form (CRF), in which the variables have been developed by the steering committee in accordance with the international standards.30–32 The initial version of the CRF has been generated by the coordinating investigator team and optimised gradually within 1 year preregistration in the coordinating centre.

Clinical information will be extracted from the medical records or through patient interviews by research assistants, including demographics, risk factors, previous medical history, prehospital care, characteristics and time course of symptom complex, physical examination, initial diagnostic impression, initial and further diagnostic tests (ie, ECG test, laboratory test and imaging examination), medication use, ED physician’s interpretation of risk level, triage in ED, costs, final ED diagnosis and discharge status. The arrival time is defined as the earliest time documented in the record. Timing of ECGs will be recorded as the time documented within the paper reports. Timing of cardiac markers is defined as the time at which the blood is drawn. The sites for triage in ED will include the emergency care unit, the observation unit and the general clinic unit of the individual hospital.

For the primary analysis, episodes of care will be evaluated for key performance measures such as the time to first ECG, receipt of troponin testing, receipt of primary reperfusion therapy for ST segment elevation ACS and provision of angiography for troponin-positive patients. The secondary measures to be evaluated include: receipt of non-invasive cardiac imaging tests for patients with suspected ACS, definite ACS, troponin-positive test and ischaemia in initial ECG; receipt of angiography for patients with suspected ACS, definite ACS and ischaemia in initial ECG; receipt of reperfusion therapy for patients with suspected ACS, definite ACS, troponin-positive test and ischaemia in initial ECG; hospital admission rate. Variables collected and performance measures in the study are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Variables and performance measures to be collected

| Category | Elements |

| Demographics | Unique patient ID, sex, age, marital status, nationality, occupation, education, insurance payer, mode of arrival |

| Risk factors | Tobacco use, family history of premature CAD, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, renal insufficiency, chronic lung disease |

| Medical history | Angina, MI, catheterisation with stenosis ≥50%, revascularisation, heart failure, PAD, cerebrovascular events (stroke), use of aspirin within 7 days |

| Prehospital care | Time of symptoms onset, time of decision to seek physician, prehospital medication and ECG examination |

| ED presentation | Character of chief complaint, associated symptoms, time course of symptom complex, vital signs at time of presentation, evidence of heart failure, height, weight, time of arrival |

| Initial evaluation | Serial ECGs and timing, ECG interpretation, serial cardiac markers and timing, values of cardiac markers, estimated risk level, initial diagnostic impression |

| Further diagnostic testing | Stress testing, non-invasive angiogram, chest X-ray, UCG, diagnostic coronary angiography |

| Patient course | Medications given in ED, reperfusion therapies for ACS (thrombolysis, primary PCI and CABG surgery), triage in ED, costs in ED, triage after ED |

| Outcomes | MACE (death from all causes, non-fatal AMI, urgent revascularisation, stroke, cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock), ED revisiting, rehospitalisation |

| Primary measures | The time to first ECG; receipt of troponin testing; receipt of primary reperfusion therapy for ST segment elevation ACS; provision of angiography for troponin-positive patients |

| Secondary measures | Receipt of non-invasive cardiac imaging tests for patients with suspected ACS, definite ACS, troponin-positive test and ischaemia in initial ECG; receipt of angiography for patients with suspected ACS, definite ACS and ischaemia in initial ECG; receipt of reperfusion therapy for patients with suspected ACS, definite ACS, troponin-positive test and ischaemia in initial ECG; hospital admission rate |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD, coronary artery disease; ED, emergency department; ID, identity document; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; UCG, ultrasonic cardiogram.

Follow-up will be conducted by research assistants in participating hospitals through telephone interviews at 30 days from the date of enrolment. The follow-up interviews are aimed to acquire information about MACE, representation to ED and rehospitalisation during the 30 days following initial presentation. These events will be confirmed by the research coordinators together with the principal investigator through reviewing related medical records.

Information obtained will be recorded on paper CRF and then keyed into online electronic data capture system, which is integrated into the clinical research management platform enabling real-time data monitoring. This monitoring is composed of three important aspects for quality control. First, the algorithmic quality checking systems will monitor for the missing and implausible data automatically. Second, investigators in participating sites will review and confirm the whole CRF and medical records to ensure the authenticity and integrity of each variable. Third, online monitoring could be executed by quality control group of the coordinating centre on a daily basis to confirm that the data meet the study requirements.

Clinical outcomes

The primary outcome is a MACE during the 30 days after presentation to the ED, including death from all causes, non-fatal myocardial infarction, urgent revascularisation, stroke, cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock. The secondary outcomes include representation to the ED and rehospitalisation within 30 days.

Adjudication process

Each event in MACE will be independently adjudicated by two physicians of clinical events committee in the coordinating centre using all available clinical records according to the international standardised definitions,30 32 33 and discrepancies will be evaluated by a third senior physician. Each case fatality will be either confirmed on a death certificate from the local death registry or from the attended hospital. MI is defined as detection of the rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarkers (preferably troponin) with at least one value above the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit (URL) and with symptoms or ECG changes indicative of new ischaemia.33 Stroke is defined as an acute episode of focal or global neurological dysfunction caused by brain, spinal cord or retinal vascular injury as a result of haemorrhage or infarction. Cardiogenic shock is defined as persistent (>30 min) systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg and/or cardiac index <2.2 L/min/m2 secondary to cardiac dysfunction, requiring intravenous inotropic or mechanical support.30

The ultimate diagnoses of patients admitted to hospitals will also be adjudicated in the same way. Unstable angina (UA) is defined as typical angina pectoris (or equivalent type of ischaemic discomfort) without any biochemical evidence of myonecrosis and with at least one of the following features: angiographic evidence of new ≥70% lesion and/or thrombus in an epicardial coronary artery, positive stress test result or new ischaemic ECG changes.30

Statistical analysis

Descriptive, univariate and multivariate analyses will be conducted. Descriptive analysis of continuous variables will be expressed as the mean±SD or the median with IQR according to normality. Categorical data will be summarised as the frequency and proportions. Patient and hospital characteristics will be compared between hospital strata (see the site selection section) using standard parametric and non-parametric techniques where appropriate. The primary analysis will be based on the episode of care. Representations to hospital within 30 days will be considered an outcome of that episode of care, while representations after 30 days will be considered a new episode of care. Using an analysis based on patient-level 30-day episodes of care, the primary analysis will compare the incidence of MACE between rural hospitals and urban hospitals through generalised estimating equation methods allowing for correlated outcomes within the same hospital and representation of the same patient. Correlations between the percentage of achievement for each described hospital performance measure (ie, table 2) and the 30-day MACE will be conducted and plotted adjusting for differences in patient characteristics (ie, age, gender, known prior coronary artery disease, diabetes and hypertension, smoking status). A P value of less than 0.05 (two-sided significance testing) will be considered statistically significant in the analysis. All analyses will be conducted using R software (R Development Core Team, http://www.R-project.org/) and SAS V.9.4.

Ethics and dissemination

This study requires patients to provide informed consent as many variables can only be obtained through interview with patients. The personal and health information of patients will be protected.

Discussion

EMPACT will inform clinicians about the characteristics, evaluation, treatment and 30-day outcomes of patients with acute chest pain and suspected ACS presenting to the ED in China. This study will describe the triage and flow of patients, defining the incidence of various diagnoses, rates of presentation and time intervals of cardiac markers and further diagnostic testing practices. Specifically, relationships between evaluation, treatment and outcomes across different levels of hospitals will be analysed. Such data will be used to improve emergency care quality for subsequent patients.

EMPACT is the first attempt to comprehensively evaluate the current emergency care in the assessment and management of patients with acute chest pain and ACS-related symptoms from a regional representative sample in China. Due to China’s vast expanses, encompassing one-fifth of the world’s population, data from national or large regional registry is important to gain a more representative estimate of current practice. To date, efforts to coordinate the emergency resources for the whole region have been undertaken. A network for research and clinical practice improvement has been established involving the sampled hospitals, using a standardised data collecting system and unified data management centre. This clinical research quality network remains a central ongoing motivation of this project. Future aims of this initiative will be to develop risk prediction scoring systems and protocols for clinical decision-making and to optimise pathways for stratification, management and triage of this population in the ED.

EMPACT has several limitations. Chinese emergency medicine is only 30 years old as an official medical domain. It is faced with several challenges, including increasing visits, ED crowding and ED boarding, high rates of hospitalisation, physicians’ work overload and underdeveloped ‘software’.34 35 First, quite a number of the EDs are not yet equipped with electronic medical records systems nor the structured data collection methods enabling national data reporting. Furthermore, handwritten medical records are always taken home by patients after discharge. This situation raises the potential for missed identification of eligible patients. Second, follow-up information including MACE, ED representation and rehospitalisation requires confirmation by reviewing related medical records, but patient refusal for access to records may lead to the underestimation of the total events. In addition, since many cities’ medical insurance policies reimburse the hospitalisation costs but not emergency spending, variations in local funding policies may influence the likelihood of hospitalisation for subsequent testing. Consequently, the ED function of triaging patients efficiently may be biased, though adjusting for these factors in exploratory analyses will be undertaken.

As the initial phase of a systematic programme for the continuous improvement, EMPACT has been designed to provide the first-hand knowledge to facilitate the emergency care improvements and valuable experiences for further studies. It will establish a precedent for more comprehensive databank and network of all the visits to ED in this region, with the potential to extend to the whole of China and even other developing countries.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

WZ, JW and FX contributed equally.

Contributors: YC contributed to the initiation, planning and conduction of the study. WZ, JW, HZ, JM, GW and JZ conducted the study supervision. WZ, JW and FX contributed equally to the manuscript of protocol. DPC advised on the study design and performed a critical revision of the manuscript. HW provided the statistical analysis. JW, WZ and HW performed the analysis and interpretation of data.

Funding: This work was supported by Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong Province (ts20130911), Taishan Young Scholar Program of Shandong Province (tsqn20161065), Key Technology Research and Development Program of Science and Technology of Shandong Province (2014kjhm0102), Department of Science and Technology of Shandong Province (2014GSF118111, 2016GSF201235, 2016ZDJS07A14).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: EMPACT has been approved by the central ethics committee at Qilu Hospital of Shandong University. All collaborating hospitals accepted the central ethics approval except for one hospital, which obtained local approval by internal ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Public Use Micro-Data File Documentation. Atlanta: National Center for Health Statistics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodacre S, Cross E, Arnold J, et al. The health care burden of acute chest pain. Heart 2005;91:229–30. 10.1136/hrt.2003.027599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meng Q, Xu L, Zhang Y, et al. Trends in access to health services and financial protection in China between 2003 and 2011: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;379:805–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60278-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. China public health statistical yearbook 2007. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College publishing house, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. China public health statistical yearbook 2015. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College publishing house, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xue J, Han Z, Wang M, et al. Main etiologies for patients presented to ER with chest pain or chest pain equivalent. Clinical Medicine of China 2012;28:1042–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2015;2016:267–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;2014:e139–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cullen L, Greenslade J, Merollini K, et al. Cost and outcomes of assessing patients with chest pain in an Australian emergency department. Med J Aust 2015;202:427–32. 10.5694/mja14.00472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Bluemke DA, et al. Testing of low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;122:1756–76. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181ec61df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, et al. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1163–70. 10.1056/NEJM200004203421603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Christenson J, Innes G, McKnight D, et al. Safety and efficiency of emergency department assessment of chest discomfort. CMAJ 2004;170:1803–7. 10.1503/cmaj.1031315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schull MJ, Vermeulen MJ, Stukel TA. The risk of missed diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction associated with emergency department volume. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:647–55. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Montassier E, Batard E, Gueffet JP, et al. Outcome of chest pain patients discharged from a French emergency department: a 60-day prospective study. J Emerg Med 2012;42:341–4. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.11.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Than M, Herbert M, Flaws D, et al. What is an acceptable risk of major adverse cardiac event in chest pain patients soon after discharge from the emergency department? A clinical survey. Int J Cardiol 2013;166:752–4. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chew DP, Scott IA, Cullen L, et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes 2016. Heart Lung Circ 2016;25:895–951. 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.06.789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Skinner JS, Smeeth L, Kendall JM, et al. NICE guidance. Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent onset chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin. Heart 2010;96:974–8. 10.1136/hrt.2009.190066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Erhardt L, Herlitz J, Bossaert L, et al. Task force on the management of chest pain. Eur Heart J 2002;23:1153–76. 10.1053/euhj.2002.3194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Than M, Cullen L, Reid CM, et al. A 2-h diagnostic protocol to assess patients with chest pain symptoms in the Asia-Pacific region (ASPECT): a prospective observational validation study. Lancet 2011;377:1077–84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60310-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lindsell CJ, Anantharaman V, Diercks D, et al. The Internet Tracking Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (i*trACS): a multicenter registry of patients with suspicion of acute coronary syndromes reported using the standardized reporting guidelines for emergency department chest pain studies. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:666–77. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Paichadze N, Afzal B, Zia N, et al. Characteristics of chest pain and its acute management in a low-middle income country: analysis of emergency department surveillance data from Pakistan. BMC Emerg Med 2015;15 Suppl 2:S13 10.1186/1471-227X-15-S2-S13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Riesgo G, Martínez E, Loma-Osorio A, et al. The characteristics and management of patients with non-traumatic chest pain in hospital emergency departments. The results of the EVICURE II study. Emergencias 2008;20:391–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eslick GD, Talley NJ. Natural history and predictors of outcome for non-cardiac chest pain: a prospective 4-year cohort study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008;20:989–97. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01133.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jiang L, Krumholz HM, Li X, et al. Achieving best outcomes for patients with cardiovascular disease in China by enhancing the quality of medical care and establishing a learning health-care system. Lancet 2015;386:1493–505. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00343-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li J, Li X, Wang Q, et al. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in China from 2001 to 2011 (the China PEACE-Retrospective Acute Myocardial Infarction Study): a retrospective analysis of hospital data. Lancet 2015;385:441–51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60921-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li J, Dharmarajan K, Li X, et al. Protocol for the China PEACE (Patient-centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events) retrospective study of coronary catheterisation and percutaneous coronary intervention. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004595 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Y, Miao Z, Wang Y, et al. Protocol for a prospective, multicentre registry study of stenting for symptomatic intracranial artery stenosis in China. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005175 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang Y, Cui L, Ji X, et al. The China National Stroke Registry for patients with acute cerebrovascular events: design, rationale, and baseline patient characteristics. Int J Stroke 2011;6:355–61. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Minister of Health. Acts for Hospital Classification. China: Minister of Health, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cannon CP, Brindis RG, Chaitman BR, et al. ACCF/AHA key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes and coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Acute Coronary Syndromes and Coronary Artery Disease Clinical Data Standards). Circulation 2013;2013:1052–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hollander JE, Blomkalns AL, Brogan GX, et al. Standardized reporting guidelines for studies evaluating risk stratification of ED patients with potential acute coronary syndromes. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:1331–40. 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, et al. ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular Endpoint Events in Clinical Trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards). J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;2015:403–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2551–67. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wen LS, Xu J, Steptoe AP, et al. Emergency department characteristics and capabilities in Beijing, China. J Emerg Med 2013;44:1174–9. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.07.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hou XY, FitzGerald G. Introduction of emergency medicine in China. Emerg Med Australas 2008;20:363–9. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2008.01108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.