Abstract

Objective

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) has been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk. A research project performed at a university hospital in Denmark offered an expanded CR intervention to socially vulnerable patients. One-year follow-up showed significant improvements concerning medicine compliance, lipid profile, blood pressure and body mass index when compared with socially vulnerable patients receiving standard CR. The aim of the study was to perform a long-term follow-up on the socially differentiated CR intervention and examine the impact of the intervention on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal recurrent events and major cardiac events (MACE) 10 years after.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

The cardiac ward at a university hospital in Denmark from 2000 to 2004.

Participants

379 patients aged <70 years admitted with first episode myocardial infarction (MI). The patients were defined as socially vulnerable or non-socially vulnerable according to their educational level and their social network. A complete follow-up was achieved.

Intervention

A socially differentiated CR intervention. The intervention consisted of standard CR and additionally a longer phase II course, more consultations, telephone follow-up and a better handover to phase III CR in the municipal sector, in general practice and in the patient association.

Main outcome measures

All-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal recurrent events and MACE.

Results

There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality (OR: 1.29, 95% CI 0.58 to 2,89), cardiovascular mortality (OR: 0.80, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.09), non-fatal recurrent events (OR:1.62, 95% CI 0.67 to 3.92) or MACE (OR: 1.31, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.42) measured at 10-year follow-up when comparing the expanded CR intervention to standard CR.

Conclusions

Despite the significant results of the socially differentiated CR intervention at 1-year follow-up, no long-term effects were seen regarding the main outcome measures at 10-year follow-up. Future research should focus on why it is not possible to lower the mortality and morbidity significantly among socially vulnerable patients admitted with first episode MI.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, Angina pectoris, Cardiac rehabilitation, Social support, Educational status, Single person, Marital status, Vulnerable populations, Treatment outcome, Mortality.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first longitudinal study to analyse the long-term effects of a socially differentiated cardiac rehabilitation intervention given to patients admitted with first episode myocardial infarction, which provide knowledge in better understanding how to reduce social inequalities in health.

Highly valid Danish register data were used that combined with a unique personal 10-digit civil registration number that is given to all citizens living in Denmark provides the study with a complete follow-up.

The study was not carried out as a randomised controlled trial. To minimise potential confounding, regression analysis was used. Moreover, the patients were almost similar at baseline.

The intervention given in the study was designed as a ‘realistic intervention’. The aim was to create an intervention that would be affordable and applicable to most rehabilitation centres if proven effective.

Patients from non-parallel time periods were being compared. All analyses were performed on both the socially and non-socially vulnerable patients. A difference between the non-socially vulnerable patients could have indicated that any changes among the socially vulnerable patients were just a general development in risk management and secondary prevention.

Introduction

According to the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a leading cause of mortality and morbidity, although CVD mortality has declined considerably in the past 20 years.1 However, the 1-year mortality rate is around 20% in patients with myocardial infarction (MI). Among the patients who survive, 20% will experience a recurrent MI within 1 year.2 It is estimated that recurrent events are caused by progression of coronary and systemic atherosclerosis.2 Secondary prevention including cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is therefore essential to improve the long-term prognosis of patients with MI and to improve their quality of life and functional capacity.2 3 CR consists of multidisciplinary interventions with focus on risk assessment and management.2

A recent Cochrane meta-analysis and a review examining the effect of exercise-based CR with at least 6-month follow-up found that CR significantly improved psychological function and reduced cardiovascular mortality.4 5 Another recent meta-analysis reported that CR containing lifestyle modification programmes significantly reduced recurrent events, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality if CR combined goal setting, self-monitoring, planning and feedback.6 Two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examined the effect of an expanded CR intervention. One of the interventions consisted of different lifestyle modification activities as well as stress management therapy. The other of the interventions consisted of exercise-based CR. At 3-year and 5-year follow-ups, the patients randomised to receive expanded CR experienced fewer non-fatal recurrent events and a lower cardiovascular mortality compared with patients receiving standard CR.7 8

Patients with low socioeconomic status, defined by their social class, educational level, income, occupation and marital status, are less likely to participate in and complete CR.9–11 This is also seen in patients with MI when focusing on mortality and non-fatal recurrent events.12–15 Patients with a low educational level have a significantly higher long-term mortality than patients with a high educational level.16 Likewise, patients living alone have a significantly higher long-term mortality risk compared with patients living with a partner.17

On a cardiac ward at a university hospital in Denmark, a socially differentiated CR intervention was performed from 2000 to 2004. The aim of the intervention was to target the social groups at highest risk of not participating in CR, not completing CR and who have the poorest long-term outcomes. The intervention was designed as a ‘realistic intervention’ based on the health professionals’ experiences. The idea of the ‘realistic intervention’ was that it should be affordable and practical to implement if proven effective. Patients defined as socially vulnerable received expanded CR, and outcome was compared with socially vulnerable patients receiving standard CR according to international guidelines. At 1-year follow-up, patients in the intervention group had significantly better results in relation to medicine compliance, lipid profile, blood pressure and body mass index.18

The aim of the present study was to perform a long-term follow-up on the socially differentiated CR intervention and examine the impact of the intervention on mortality and non-fatal recurrent events 10 years after.

Methods

Study design

This is a prospective cohort study. Patients were followed from baseline, defined as time of admission with first episode of MI, and during the next 10 years. Follow-up was performed at the exact day 10 years after their admission.

The 4-year socially differentiated CR intervention was carried out on a cardiac ward at a university hospital in Denmark between 2000 and 2004.

This study focuses on the socially vulnerable patients who received expanded CR compared with those who received standard CR.

Patient population

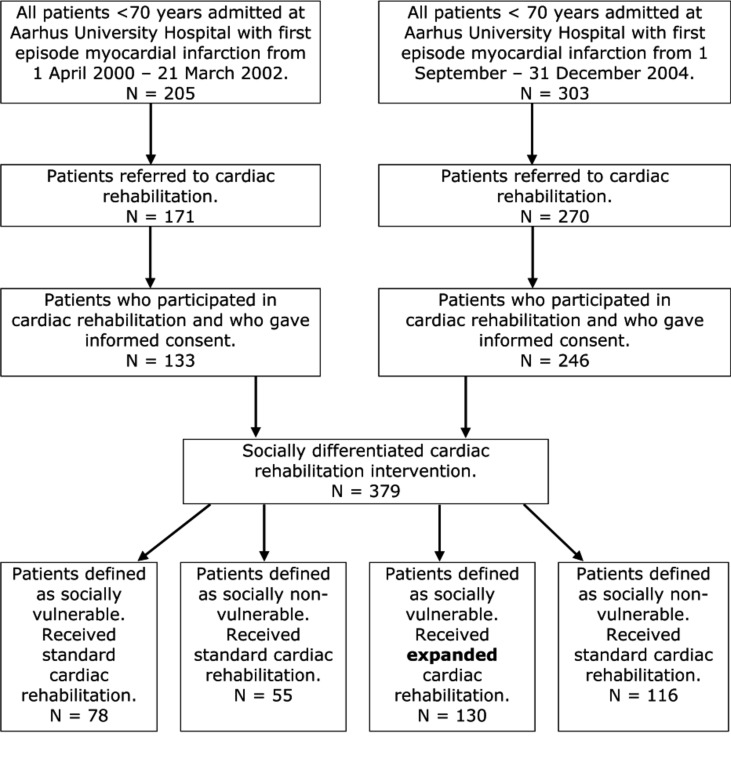

From 1 April 2000 to 31 March 2002, all patients aged <70 years admitted with first episode of MI were systematically identified. Of the 205 patients with MI, 171 were referred to standard CR; 133 patients gave informed consent to participate. Of these, 78 patients were categorised as socially vulnerable and 55 were categorised as non-socially vulnerable. All of the 133 patients received standard CR according to international guidelines.

From 1 September 2002 to 31 December 2004, all patients aged <70 years admitted with first episode of MI were assessed by a project nurse and referred to either standard CR or expanded CR. A total of 303 patients were admitted; 270 patients were referred to CR of whom 246 patients gave informed consent to participate. Of these, 130 patients were categorised as socially vulnerable and received expanded CR, and the remaining 116 patients were categorised as non-socially vulnerable and received standard CR.

Patients were defined as socially vulnerable if they had: (1) low educational level (education classified 1–4 in the Danish Educational Nomenclature if age <55 years and 1–3 if age >55 years) and/or (2) if they lived alone. Patients were defined as non-socially vulnerable if they did not meet the criteria above.

Patients were excluded if they suffered from severe comorbidities such as stroke, dementia, mental disorders, retardation or severe alcohol abuse. Patients suffering from depression or anxiety were not excluded.

The study population, categorisation and CR characteristics are described in detail in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study participants.

Exposure

The expanded CR intervention consisted of standard CR and a longer phase II course, more consultations, telephone follow-up and a better handover to phase III CR in the municipal sector, in general practice and in the patient association.

The standard CR intervention was consistent with international guidelines.

The differences between the two CR interventions are described in detail in table 1.

Table 1.

Content of the socially differentiated cardiac rehabilitation intervention

| Standard cardiac rehabilitation | Expanded cardiac rehabilitation | |

| Phase I Acute treatment until discharge |

|

Like standard cardiac rehabilitation |

| Phase II Discharge from hospital until return to vocational activities |

|

Like standard cardiac rehabilitation and:

|

| Phase III Further course after phase II |

|

Like standard cardiac rehabilitation and:

|

Study outcomes

The main outcome measures in the present study were all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal recurrent events (MI and unstable angina pectoris) and major cardiac events (MACE) defined as cardiovascular mortality and non-fatal recurrent events. The endpoints were adjusted for gender, age, diabetes and smoking status at baseline.

Data sources

Baseline patient data were collected at admission from clinical databases and from questionnaires filled in by the patients. In 1968, The Danish Civil Registration System was introduced. The system provides all persons living in Denmark with a unique personal 10-digit civil registration number. This number was used to link the study population to different registers ensuring a high validity and completeness. Endpoint data concerning mortality were collected from The Danish Cause of Death Register established in 1970. Cardiovascular mortality was defined using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). Data on non-fatal recurrent events were retrieved using the ICD-10 from The Danish National Patient Registry established in 1977.

Statistics

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as mean with SD. The Kaplan-Meier estimate plots were used to evaluate survival probability and event-free probability. Logistic regression was applied when performing adjusted analyses. All endpoints are presented as ORs with 95% (CIs) and P values. A significance level of 0.05 was applied. When performing the adjusted analyses, the rule of 10 was used. All statistical analyses were carried out using the statistics software program Stata V.14.1.

Results

Baseline characteristics

From 1 April 2000 to 31 December 2004, 379 patients were referred to and participated in a socially differentiated CR intervention receiving either a standard or expanded CR intervention (figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the patients are given in table 2. A complete follow-up after 10 years was achieved.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics at patient admission with first episode myocardial infarction (n=379)

| Socially vulnerable patients | Non-socially vulnerable patients | |||

| Rehabilitation type N Time period |

Rehabilitation type N Time period |

|||

| Standard n=78 2000–2002 (%/SD) |

Expanded n=130 2002–2004 (%/SD) |

Standard n=55 2000–2002 (%/SD) |

Standard n=116 2002–2004 (%/SD) |

|

| Age, years | 56 (8.15) | 55 (8.53) | 60 (7.56) | 57 (8.50) |

| Gender, male | 57 (73) | 93 (71) | 42 (76) | 94 (81) |

| Educational level, The Danish Educational Nomenclature | 3.18 (1.19) | 3.26 (1.39) | 4.80 (1.08) | 4.75 (1.19) |

| Living alone | 27 (35) | 51 (39) | 0 | 0 |

| Current smoker | 59 (76) | 83 (64) | 34 (62) | 60 (52) |

| Body mass index | 27.26 (4.35) | 26.26 (4.08) | 26.37 (3.99) | 26.54 (3.12) |

| Hypertension | 18 (23) | 28 (22) | 11 (20) | 23 (20) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 20 (26) | 37 (28) | 13 (24) | 44 (38) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (13) | 16 (12) | 6 (11) | 10 (9) |

All-cause mortality

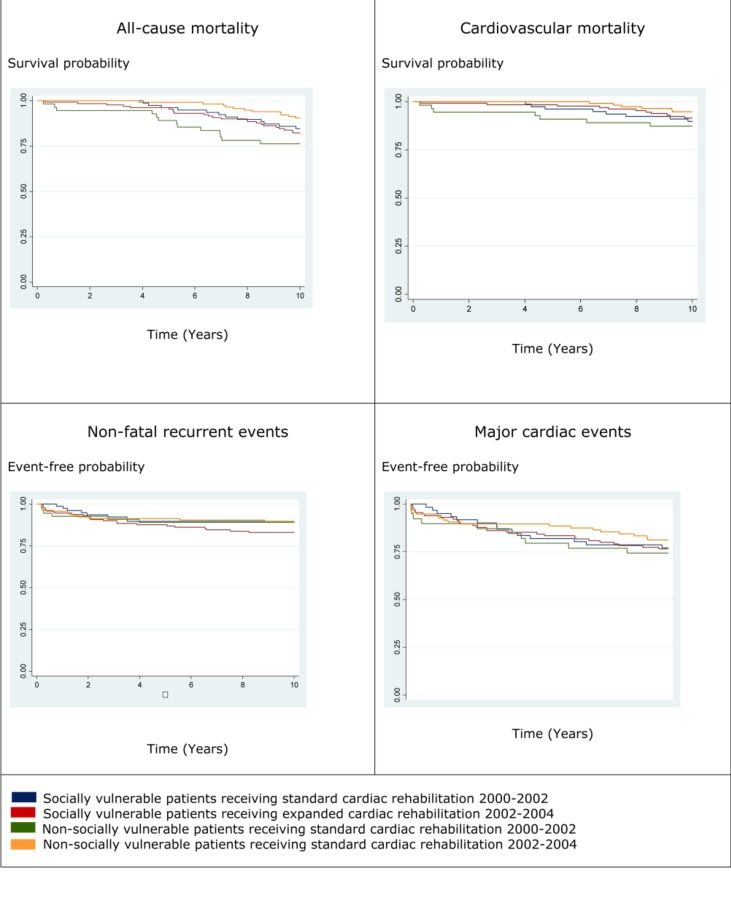

A total of 17% of the vulnerable patients died during the 10-year follow-up period; 18% of these patients had received expanded CR and 15% had received standard CR. No significant differences were found between the two groups as an OR of 1.29 (95% CI 0.58 to 2.89), and a P value of 0.53 was obtained (table 3). As indicated in figure 2, no significant associations were found at 10-year follow-up among the non-socially vulnerable patients receiving standard CR.

Table 3.

Endpoints at 10-year follow-up among socially vulnerable patients admitted with first episode myocardial infarction and participating in socially differentiated cardiac rehabilitation in the period from 2000 to 2004

| Total (n=208) |

Expanded cardiac rehabilitation (n=130) |

Standard cardiac rehabilitation (n=78) |

OR (95% CI) |

P value | |

| All-cause mortality* | 35 (17) | 23 (18) | 12 (15) | 1.29 (0.58 to 2.89) | 0.53 |

| Cardiovascular† | 19 (9) | 11 (8) | 8 (10) | 0.80 (0.31 to 2.09) | 0.65 |

| Total (n=176‡) |

Expanded cardiac rehabilitation (n=115‡) |

Standard cardiac rehabilitation (n=61‡) |

OR (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Non-fatal recurrent events* | 30 (17) | 22 (19) | 8 (13) | 1.62 (0.67 to 3.92) | 0.29 |

| Major cardiac events§ | 41 (23) | 27 (23) | 14 (23) | 1.31 (0.53 to 2.42) | 0.75 |

Data are given as numbers (percentage).

*Adusted for gender, age and diabetes mellitus.

†Adjusted for gender.

‡Only patients who did not suffer from a recurrent event during the first month after admission were included in the analysis.

§Adjusted for gender, age, diabetes and smoking status.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal recurrent events and major cardiac events.

Cardiovascular mortality

Among the vulnerable patients, 9% suffered from cardiovascular mortality. Of the patients receiving expanded CR, 8% died compared with 10% among patients receiving standard CR. No significant differences were found at 10-year follow-up; OR 0.80 (95% CI 0.31 to 2.09) and P value 0.65 (table 3). As indicated in figure 2, no significant associations were found at 10-year follow-up among the non-socially vulnerable patients receiving standard CR.

Non-fatal recurrent events

Only patients who did not experience a non-fatal recurrent event during the first 30 days after admission were included in the analysis. A total of 17% of the vulnerable patients experienced a non-fatal recurrent event during the 10-year follow-up; among these, 19% received expanded CR and 13% received standard CR. No significant differences were found between the two groups; OR 1.62 (95% CI 0.67 to 3.92) and a P value of 0.29 (table 3). As indicated in figure 2, no significant associations were found at 10-year follow-up among the non-socially vulnerable patients receiving standard CR.

Major cardiac events

The percentage of vulnerable patients who either experienced cardiovascular mortality or experienced a non-fatal recurrent event within 30 days after admission until 10-year follow-up was 23% in total and in each group. No significant differences were seen between the two groups; OR 1.31 (95% CI 0.53 to 2.42) and a P value of 0.63 (table 3). As indicated in figure 2, no significant associations were found at 10-year follow-up among the non-socially vulnerable patients receiving standard CR.

Discussion

Study findings

There were no significant differences between socially vulnerable patients admitted with first episode MI receiving expanded CR and socially vulnerable patients receiving standard CR concerning the four endpoints: all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal recurrent events and MACE at 10-year follow-up (table 3). Moreover, no significant results were found at 10-year follow-up among the non-socially vulnerable patients who all received standard CR.

Comparison with other studies

Two studies have examined the effect of an expanded CR intervention. In a Swedish RCT by Plüss et al,7 224 patients aged <75 years with recent MI and/or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) were randomised to either expanded CR or standard CR between 1999 and 2002 and followed for 5 years. Patients were excluded if suffering from a significant psychiatric disease or alcohol abuse. All patients received 3 months of standard CR including consultations with health professionals and a social worker, physical exercise, patient education and advice on smoking cessation. The patients receiving the expanded intervention also stayed 5 days at a patient hotel after discharge, where they participated in a cooking school for 3 weeks and attended a stress management course for 1 year. The study had an almost complete follow-up and a significantly lower number of the patients in the intervention group suffered a non-fatal recurrent event at 5-year follow-up (hazard rate 0.47, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.97, P value 0.04). No significant results were found regarding all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.7

The study by Plüss et al 7 has many similarities with the present study. Sweden and Denmark have similar welfare states with the same access to free healthcare and social services. The patients in the two studies were recruited in the same time period and had comparable characteristics concerning disease and age. Furthermore, exclusion criteria were the same. However, the Swedish in contrast to the present study found significant results. This could be explained by the Swedish intervention being more pervasive and lasting a whole year and thereby constituting a major part of the long-term secondary prevention. Furthermore, the Swedish intervention was not socially differentiated. It could thus be speculated that the patients who profited the most from the intervention were the patients who were not socially vulnerable.

In an Italian RCT by Giannuzzi et al,8 3241 patients aged <75 years with recent MI were randomised to either expanded CR or usual care. At first, all patients received the same standard CR for 1 month consisting of physical training, lifestyle consultations and medical therapy. Hereafter 1621 patients continued in usual care, and 1620 patients received an expanded CR intervention. The expanded CR intervention consisted of 2 hours of counselling and physical training every month for half a year and thereafter every 6 months for 3 years. Compared with usual care the expanded CR intervention showed significant improvements concerning cardiovascular mortality and recurrent events. The study by Giannuzzi et al 8 differs from the present study regarding to the time frame of the intervention. The intervention lasted for 3 years, and thus it was an important part of the long-term secondary prevention like Plüss et al.7 Also, the outcomes was collected at the end of the 3-year intervention and do not hold any information about the long-term effects.8

Strengths, limitations and external value of the study

One of the strengths of the present study is the complete follow-up. This is partly because the patients were identified by their unique personal 10-digit civil registration number and partly because of the use of highly valid Danish register data. The information concerning mortality and morbidity were registered by health professionals using ICD-10 and did thus not rely on the memory of patients or relatives. Another strength is that the patients were almost similar at baseline. The only variables with considerable variation were educational level and whether the patients lived alone. This could be explained by these variables defining whether patients were socially vulnerable or not. It should, however, be noted that smoking status and the presence of hyperlipidaemia also varied.

The fact that patients from non-parallel time periods were being compared raises some methodological issues. All analyses were performed on both the socially and non-socially vulnerable patients. A difference between the non-socially vulnerable patients could have indicated that any changes among the socially vulnerable patients were just a general development in risk management and secondary prevention. However, no significant differences were found.

The present study was carried out as a prospective cohort study and not as an RCT, thus there is a risk of confounding and bias. An attempt to minimise potential confounding was made by using logistic regression analysis. Potential information bias cannot be ruled out concerning the self-reported questionnaires. However, it must be expected that potential bias must be non-differentiated and thereby changing the results towards the null hypothesis. A risk of selection bias could occur as attendance rates were significantly higher in the time period of the intervention than in the period where the control group received standard CR. If more highly socially vulnerable patients participated in the intervention, then it could be difficult to see any significant results of the intervention if they were compared with the low-risk part of the socially vulnerable patients in the group receiving standard CR.

A reason that no significant changes were found between the socially vulnerable patients receiving expanded CR and the ones receiving standard CR could be that standard CR is an evidence-based, structured and multidisciplinary intervention of high quality that any significant changes due to the expanded CR would be hard to detect. The mean age of the patients were around late 50s. Any changes in hard endpoints such as mortality and non-fatal recurrent events could be lacking, because it must be expected that the patients have had an unhealthy life style for many years resulting in severe irreversible atherosclerosis. Also, the non-significant results could indicate the importance of phase III CR. More focus should be placed on supporting the patients in the long-term CR similar to the study by Plüss et al 7 and trying to maintain and strengthen the knowledge that the patients obtain during phase II CR.

The external validity of the present study could be applied to CR in a hospital setting in most western countries, especially countries with free healthcare and a wide access to social services.

Future research

Future research should focus on why it was not possible to lower the mortality and morbidity significantly among socially vulnerable patients admitted with first episode MI. The authors suggest at least three plausible explanations that could be helpful when designing new interventions. (1) Maybe it is not possible to lower social inequality in mortality and morbidity by using socially differentiated interventions. (2) Maybe the expanded CR should have focused on other things such as stress reduction, mindfulness or coping like it was the case in Plüss et al 7 and in another recently published RCT focusing on stress management training.19 (3) Perhaps the intensity and the time frame were wrong. In Plüss et al,7 the expanded intervention lasted 1 year, and the patients therefore received support in phase II and in phase III as a part of the long-term secondary prevention.7 In order to minimise the costs and maximise the benefit of a more intense and longer CR programme, alternate low-resource settings and interventions such as digital devices and home-based CR must be considered as well as a focus on those patients who will benefit mostly on participation.20 21

Conclusion

Despite the significantly improved results of the socially differentiated CR intervention at 1-year follow-up, no long-term significant effects were seen regarding mortality and non-fatal recurrent events at follow-up after 10 years.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the work. All authors contributed to acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. KH and MLL drafted the manuscript. KMN, LKM, FBL, BC and CVN critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Funding: The authors disclosed received financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article by: Aarhus University (17117581), Central Denmark Region (A-111 and 1-15-1-72-13-09), The Health Foundation (16-13-0098), The Committee of Multipractice Studies in General Practice (16-1461) and Trygfonden (119795).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by The Danish Data Protection Agency (case number: 1-16-02-684-14). Ethical approval is not required for register-based studies in Denmark.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Rev Esp Cardiol 2016;2016:1–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Piepoli MF, Corrà U, Dendale P, et al. Challenges in secondary prevention after acute myocardial infarction: A call for action. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:1994–2006. 10.1177/2047487316663873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smolina K, Wright FL, Rayner M, et al. Long-term survival and recurrence after acute myocardial infarction in England, 2004 to 2010. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012;5:532–40. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1–12. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lavie CJ, Menezes AR, De Schutter A, et al. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training on psychological risk factors and subsequent prognosis in patients with cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:S365–373. 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.07.508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Janssen V, De Gucht V, Dusseldorp E, et al. Lifestyle modification programmes for patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2013;20:620–40. 10.1177/2047487312462824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Plüss CE, Billing E, Held C, et al. Long-term effects of an expanded cardiac rehabilitation programme after myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass surgery: a five-year follow-up of a randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil 2011;25:79–87. 10.1177/0269215510376006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giannuzzi P, Temporelli PL, Marchioli R, et al. Global secondary prevention strategies to limit event recurrence after myocardial infarction: results of the GOSPEL study, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial from the Italian cardiac rehabilitation network. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:2194–204. 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mikkelsen T, Korsgaard Thomsen K, Tchijevitch O. Non-attendance and drop-out in cardiac rehabilitation among patients with ischaemic heart disease. Dan Med J 2014;61:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beauchamp A, Peeters A, Tonkin A, et al. Best practice for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease through an equity lens: a review. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:599–606. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328339cc99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laustsen S, Hjortdal VE, Petersen AK. Predictors for not completing exercise-based rehabilitation following cardiac surgery. Scand Cardiovasc J 2013;47:344–51. 10.3109/14017431.2013.859295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mårtensson S, Gyrd-Hansen D, Prescott E, et al. Does access to invasive examination and treatment influence socioeconomic differences in case fatality for patients admitted for the first time with non-ST-elavation myocardial infarction or unstable angina? EuroIntervention 2015;11:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Molshatzki N, Drory Y, Myers V, et al. Role of socioeconomic status measures in long-term mortality risk prediction after myocardial infarction. Med Care 2011;49:673–8. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318222a508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Korda RJ, Soga K, Joshy G, et al. Socioeconomic variation in incidence of primary and secondary major cardiovascular disease events: an Australian population-based prospective cohort study. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:1–10. 10.1186/s12939-016-0471-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stirbu I, Looman C, Nijhof GJ, et al. Income inequalities in case death of ischaemic heart disease in the Netherlands: a national record-linked study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:1159–66. 10.1136/jech-2011-200924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rasmussen JN, Rasmussen S, Gislason GH, et al. Mortality after acute myocardial infarction according to income and education. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:351–6. 10.1136/jech.200X.040972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Notara V, Panagiotakos DB, Papataxiarchis E, et al. Depression and marital status determine the 10-year (2004-2014) prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome: The GREECS study. Psychol Health 2015;30:1116–27. 10.1080/08870446.2015.1034720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nielsen KM, Meillier LK, Larsen ML. Extended cardiac rehabilitation for socially vulnerable patients improves attendance and outcome. Dan Med J 2013;60:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blumenthal JA, Sherwood A, Smith PJ, et al. Enhancing cardiac rehabilitation with stress Management training. A randomized, clinical efficacy trial. Circulation 2016;133:1341–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grace SL, Turk-Adawi KI, Contractor A, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation delivery model for low-ressource settings: an international council of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation consensus statement. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2016;59:303–22. 10.1016/j.pcad.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kachur S, Chongthammakun V, Lavie CJ, et al. Impact of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training programs in coronary heart disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2017;60:103–14. 10.1016/j.pcad.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.