Abstract

Background/objective

Patient-centred attitudes have been shown to decline during medical training in high-income countries, yet little is known about attitudes among West African medical students. We sought to measure student attitudes towards patient-centredness and examine validity of the 18-item Patient–Practitioner Orientation Scale (PPOS) in this context.

Participants/setting

430 medical students in years 1, 3, 5 and 6 of a 6-year medical training programme in Bamako, Mali.

Design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey, compared the proportion of students who agreed with each PPOS item by gender and academic year, and calculated composite PPOS scores. To examine psychometrics of the PPOS and its two subscales (‘sharing’ and ‘caring’), we calculated internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and performed confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses (CFA and EFA).

Results

In seven of the nine ‘sharing’ items, the majority of students held attitudes favouring a provider-dominant style. For five of the nine ‘caring’ items, the majority of student responded consistently with patient-centred attitudes, while in the other four, responses indicated a disease-centred orientation. In eight items, a greater proportion of fifth/sixth year students held patient-centred attitudes as compared with first year students; there were few gender differences. Average PPOS scores indicated students were moderately patient-centred, with more favourable attitudes towards the ‘caring’ aspect than ‘sharing’. Internal consistency of the PPOS was inadequate for the full scale (α=0.58) and subscales (‘sharing’ α=0.37; ‘caring’ α=0.48). CFA did not support the original PPOS factors and EFA did not identify an improved structure.

Conclusions

West African medical students training in Bamako are moderately patient-centred and do not show the same declines in patient-centred attitudes in higher academic years as seen in other settings. Medical students may benefit from training in shared power skills and in attending to patient lifestyle factors. Locally validated tools are needed to guide West African medical schools in fostering patient-centredness among students.

Keywords: patient-centredness, medical students, patient–provider communication, Mali, West Africa

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First study to measure patient-centred attitudes among medical students in West Africa and compare attitudes among gender and academic year.

First study to examine psychometric properties of the widely used Patient–Practitioner Orientation Scale in West Africa.

Cross-sectional design limits ability to attribute differences between academic years to an effect of time in medical training.

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa faces a myriad of public health challenges, including the continued threat of major infectious disease (such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria), high maternal and child mortality rates, poor coverage of reproductive health services and the emerging threat of chronic and non-communicable diseases.1 Confronting these challenges requires a strong healthcare workforce and systems that can consistently deliver quality care, treatment and preventative services. Unfortunately, WHO has stated concern that globally, education systems that train healthcare providers are ‘not currently well equipped to respond to the challenges of 21st century,’ particularly in low-income and middle-income countries.2 To meet these challenges, WHO calls for a ‘transformative agenda’ for health workforce education that emphasises competencies in ‘patient-centred’ care.

‘Patient-centred’ describes an orientation of medical practice that ‘consciously adopts the patient’s perspective’ by valuing the patient’s experience, acknowledging the psychosocial aspects of illness and offering the patient an equal role in decision-making.3 This core philosophy challenges heavy emphasis on biological aspects of disease and skewed balance of power in patient–provider relationships often present in healthcare. In recent decades, mounting evidence has suggested that a patient-centred style of care can lead to an array of positive outcomes, including higher patient satisfaction, increased efficiency of diagnosis and referrals, better patient adherence to medication and behavioural regimens, fewer missed appointments and even higher provider satisfaction.4–8

Widespread integration of patient-centred care in sub-Saharan Africa could result in a range of positive impacts. Research from the region has already revealed when patient-centredness is practised, it can result in better adherence to family planning methods9 and greater patient engagement in HIV care.10 Evidence also suggests that patients in sub-Saharan Africa generally prefer a patient-centred style of practice.11–13 Their providers, however, tend to be more ‘provider-dominant’ and ‘disease-centred’ in their practice orientation.14 15

Multilevel barriers have prevented patient-centred care from wide adoption in sub-Saharan Africa. The foundation of biomedical healthcare systems in the region were the rigid, hierarchical, disease-control operations established by colonial powers.16 Today, these systems are further confined by present-day international pressures to implement vertical, disease-specific programmes that prioritise easily quantifiable outputs.16 Yet one obvious reason why patient-centred care is not regularly practised is that providers are not trained to deliver it. To capitalise on the benefits for both patients and providers, training programmes for health professionals in many high-income countries are increasingly adopting curricula that promotes patient-centredness. These curricula also aim to counter the decline of patient-centred attitudes during the course of medical education observed in longitudinal studies in the USA and Greece and inferred from a number of cross-sectional studies internationally.17–21 Reductions in patient-centred attitudes in medical school may result from the heavy emphasis medical programmes place on the biological aspects of disease, as well as the emotional burn-out medical students may develop as their responsibilities and work load intensify.22 Despite evidence supporting positive outcomes of such curricula, few medical schools in sub-Saharan Africa have implemented formal programmes to promote a patient-centred orientation or teach related communication skills.23 24 Infusing patient-centredness into medical school curricula could help future providers deliver quality care and build effective health systems, but requires an understanding of existing levels and patterns of attitudes towards patient-centredness. Yet presently, research on such attitudes among medical students in sub-Saharan Africa is scarce. To our knowledge, only one peer-reviewed article has examined patient-centred attitudes among sub-Saharan African medical students; this study from South Africa found low patient-centredness that declined among students in progressively higher academic years.25 Using the Patient–Practitioner Orientation Scale (PPOS), the authors reported that students were higher in the ‘caring’ aspect of patient-centredness (‘the extent to which the respondent sees the patient’s expectations, feelings and life circumstances as critical elements in the treatment process’) than in the ‘sharing’ aspect (‘the extent to which the respondent believes that patients desire information and should be part of the decision-making process’).25 26 Results from this study, however, cannot easily be generalised to other areas of sub-Saharan Africa, considering the unique context of medical education in South Africa. South Africa is home to many of the region’s oldest medical schools, has been the setting for more peer-reviewed articles on medical education than any other country in sub-Sahara Africa and has a highly unique demographic profile of students (only 39% identify as black and 13% as coloured).24 27 To more accurately inform patient-centred curricula for schools in sub-Saharan Africa, further research is needed that assesses current attitudes among students and establishes valid measures.

We conducted our study at the medical school of the University of Sciences, Techniques and Technology of Bamako, with a student body from Mali and a number of other West African francophone countries. In addition to the aforementioned challenges of delivering patient-centred care in sub-Saharan Africa, providers in Mali face unique challenges of maintaining quality services in a highly decentralised, primary healthcare system28 and ensuring access to care in hard-to-reach rural and conflict-ridden areas.29 Our objectives were to assess patient-centred attitudes among medical students, determine if patient-centred attitudes vary according to academic year and demographic factors and test the construct validity and internal consistency of the PPOS in this setting.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of students in a six-year medical training programme at the University of Sciences, Techniques and Technology of Bamako at the start of the 2016 academic year. Participants included first year students (who train in the classroom with little to no patient contact), third year students (who have some observational exposure to patients in addition to classroom work) and fifth and sixth year students (who train in clinical locations with regular patient contact).

Measures

Originally developed in the USA,26 the PPOS has been used to assess patient-centred attitudes of medical students, providers and patients in several different countries. The tool asks participants to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with 18 statements regarding the patient–provider relationship. Responses are provided on a six-point Likert scale that ranges from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree.’ To reduce social desirability bias, most statements are negatively worded (reflecting a provider-dominant or disease-centred orientation), while a few items are worded in a positive direction (reflecting a patient-centred orientation). In the original scale development study, Krupat and colleagues reported satisfactory internal consistency (α=0.73) and a two-factor structure (‘sharing’ and ‘caring’).26 The PPOS has demonstrated moderate predictive validity with some patient-centred measures derrived from the Roter Interaction Analysis System (a tool for coding clinical dialogue), as well as with patient satisfaction outcomes.26 30

A bilingual team of medical faculty members in Mali translated the original 18 items into French and then back-translated them into English, guided by phrasing from an adaptation for patients in Sierra Leone.11 We conducted three rounds of pretesting and revisions with small groups of medical students that included the use of cognitive interviewing to ensure questions were interpreted as intended.31 We also asked participants to indicate their age, gender, whether they were raised in an urban or rural area and whether they would like to practice medicine in an urban or rural area.

Sampling and data collection

The entire student body consisted of 3846 students. To obtain a parsimonious representation of students in their early, mid and advanced years of training, we chose to administer the survey to first, third and fifth/sixth year students. Registered students in these academic years included 1214 in the first year, 571 in the third year, 415 in the fifth year and 401 in the sixth year. The larger number of students in the first year is explained by the structure of the training. After the first year, a small proportion of students pass exams admitting them to subsequent training.

To have sufficient power (1−β=0.80) to detect a small effect size for a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing the three groups (α=0.05), we aimed to sample 289 students per group. To sample first year students, we distributed and collected surveys in large lecture classes through a systematic sampling design. We also visited lectures for third year students, opening up the survey to all students attending. Fifth and sixth years are similar in structure—students are typically off-site in clinical placements. Anticipating challenges obtaining an adequate sample size for one class of students, we decided to sample both fifth and sixth year students as one group. For these students, we distributed and collected the surveys through class leaders.

Data analysis

Research assistants manually entered the paper survey data into an electronic spreadsheet, which we transferred to Stata V.13 for analysis.32 The first author double-entered a random 10% subsample of the data to assess and correct any patterns of error (which were not found). Factor analyses were conducted in MPlus V.7.33

We first conducted an item-by-item analysis by calculating the proportion of the sample that agreed with each statement (combining the proportion that responded ‘strongly agree’, ‘mostly agree’ or ‘agree’). We analysed the items in the direction they were originally posed to participants, so that higher scores would consistently represent stronger agreement with the statement. We used Pearson’s χ2 test to determine if the proportion who agreed with each statement was significantly different according to academic year or gender. We then calculated scores for the composite PPOS and the two subscales according to its original scoring methods.26 Specifically, we reverse scored positively worded items and calculated composite scores by taking the mean of non-missing items. Composite scores for the full scale and subscale have a possible range of 1–6, with higher values indicating higher patient-centredness. For each scale and subscale, we compared means across different years of medical school using one-way ANOVA, and when differences were detected, we conducted subsequent Tukey-adjusted pairwise comparisons.

To evaluate the scale’s psychometrics, we first calculated internal consistency of the PPOS and subscales using Cronbach’s alpha. We then performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the presumed two-factor structure, using a polychoric correlation structure with a robust diagonally weighted least squares estimation.25 We fixed the variances of the two factors and allowed them to correlate using a geomin (a type of oblique) rotation.34 To assess model fit, we examined a χ2 test of model fit against baseline model, and compared root mean square error approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) to a baseline model according to criteria specified by Hu and Bentler (RMSEA=0.072; CFI=0.523; TLI=0.455).35 We also examined the magnitude and statistical significance of factor loadings and item residual variance. To determine if an alternative factor structure would better fit the data, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using methods outlined by Costello and Osborne.36

Results

Sample demographics

We collected surveys from 453 students, representing 17% of the total population of students in the selected academic years. Of these, eight were discarded: five due to having greater than 20% missing data and three for having a single response choice for all questions (suggesting that the participant simply filled in one response instead of basing responses on a careful consideration of the questions). Twelve additional surveys were discarded because they were mistakenly completed by second year students who were not part of the target sample. Overall participant response rate was not possible to calculate, as surveys for fifth and sixth years students were distributed informally through social networks. Attendance at classroom lectures and the rate of distribution through social networks were lower than anticipated, resulting in a lower than expected sample size.

Of the 430 surveys analysed, 286 (66.5%) were completed by male participants; 18 (4.2%) were missing data for gender (table 1). First year students made up 57.7% of the sample, while third year students made up 23.5% and fifth/sixth year students made up 18.8%. A slight majority of students were raised in urban areas (54.9%) and 12.8% were missing a response about where they were raised. Approximately half of students reported they wanted to practice medicine in an urban area, 27.8% in a rural area, while 21.6% did not indicate a preference.

Table 1.

Demographics of sample of medical students in Bamako, Mali (n=430)

| First year, n (%) | Third year, n (%) | Fifth/sixth year, n (%) | Total sample, n (%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 157 (63.3) | 79 (78.2) | 50 (61.7) | 286 (66.5) |

| Female | 81 (32.7) | 18 (17.8) | 27 (33.3) | 126 (29.3) |

| Missing | 10 (4.0) | 4 (4.0) | 4 (4.9) | 18 (4.2) |

| Raised in: | ||||

| Rural area | 74 (29.8) | 35 (34.7) | 30 (37.0) | 139 (32.3) |

| Urban area | 139 (56.1) | 56 (55.5) | 41 (50.6) | 236 (54.9) |

| Missing | 35 (14.1) | 10 (9.9) | 10 (12.4) | 55 (12.8) |

| Want to work in: | ||||

| Rural area | 67 (27.0) | 34 (33.7) | 27 (33.3) | 123 (27.8) |

| Urban area | 129 (52.0) | 45 (44.6) | 35 (43.2) | 209 (48.6) |

| Missing | 52 (21.0) | 22 (21.8) | 19 (23.5) | 93 (21.6) |

| Total | 248 (57.7) | 101 (23.5) | 81 (18.8) | 430 (100) |

Analysis of individual patient-centredness items

In seven out of the nine sharing items, a majority of students favoured a more provider-dominant style (table 2). For example, 64% felt that the doctor should decide what is said during the consultation (item 1) and 91% believed that the pOrientation of majority of sample atient must always be conscious that the doctor should lead the consultation (item 15). In five of the nine caring items, the majority of students favoured higher caring. For example, only 27% agreed that the relation with the patient is not as important as a good diagnosis and treatment and 86% felt that humour is an important factor in treatment. Yet in the other four caring items, the majority of students responded in a manner consistent with a lower caring (or more disease-centred) orientation. For example, only 41% felt that a successful treatment plan must agree with the way a patient prefers to live their life (item 13) and 74% felt that it is more important for a doctor to have good medical techniques than interest in the social component of the patient (item 2).

Table 2.

Per cent of students in agreement with items from the PPOS with comparisons by academic year and gender

| Academic year | Academic year comparison χ2(2) | Total sample | Orientation of majority of sample | ||||

| 1 | 3 | 5/6 | |||||

| Sharing items | |||||||

| 1 | The doctor should decide what is said during the consultation | 65.3 | 56.3 | 69.7 | 3.02 | 63.9 | Provider-dominant |

| 4 | The most important part of the medical visit is the physical exam | 41.6 | 34.7 | 22.2 | 9.91** | 36.2 | Patient-centred |

| 5 | Patients should rely on the doctor’s knowledge and not try to find out about their medical condition on their own | 66.1 | 55.5 | 46.2 | 14.03** | 59.3 | Provider-dominant |

| 8 | Many patients continue asking questions even if the doctor has already given an explanation | 77.1 | 71.7 | 60.5 | 8.44* | 72.6 | Provider-dominant |

| 9 | Patients should be treated as if they were partners with the doctor, equal in power and status† | 79.0 | 71.4 | 69.1 | 4.25 | 75.4 | Patient-centred |

| 10 | Patients generally want reassurance rather than information about their health | 73.0 | 73.0 | 69.1 | 0.48 | 72.2 | Provider-dominant |

| 12 | When patients disagree with their doctor, this is a sign that the doctor does not have the patient’s respect and trust | 68.2 | 65.7 | 67.9 | 0.21 | 67.5 | Provider-dominant |

| 15 | The patient must always be conscious that the doctor should lead the consultation | 94.6 | 84.6 | 87.7 | 9.48** | 91.0 | Provider-dominant |

| 18 | When patients seek medical information outside of the clinic, this usually confuses more than it helps | 80.9 | 79.8 | 77.8 | 0.38 | 80.1 | Provider-dominant |

| Caring items | |||||||

| 2 | It is more important for doctor to have good medical techniques than it is to have interest in the social component of the patient | 82.2 | 62.0 | 60.5 | 23.3*** | 73.4 | Disease-centred |

| 3 | The most important part of the medical visit is the physical exam | 44.6 | 50.5 | 35.8 | 3.95 | 44.3 | Patient-centred |

| 6 | When doctors ask a lot of questions about a patient’s background, they are prying too much into personal matters | 66.1 | 55.5 | 43.2 | 14.03** | 59.3 | Disease-centred |

| 7 | If a doctor does a good diagnosis and treatment, the relation with the patient is not as important | 31.1 | 24.2 | 18.5 | 5.39 | 27.1 | Patient-centred |

| 11 | If a doctor focuses too much on being friendly, they will not have a lot of success | 88.6 | 83.8 | 67.5 | 19.44*** | 83.5 | Disease-centred |

| 13 | For a treatment plan to succeed, it must agree with the way a patient prefers to live their life† | 37.9 | 48.0 | 43.8 | 3.12 | 40.5 | Disease-centred |

| 14 | Most patients want to get in and out of the doctor’s office as quickly as possible | 47.1 | 41.0 | 32.1 | 5.79 | 42.8 | Disease-centred |

| 16 | It is not that important to know a patient’s background to treat the patient’s illness | 23.1 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 21.23*** | 16.0 | Patient-centred |

| 17 | Humour is an important factor in the way a doctor treats the patient† | 86.1 | 81.6 | 90.0 | 2.57 | 85.8 | Patient-centred |

*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

†Positively worded item. Unlike other items, agreement with these statement indicate a patient-centred orientation.

PPOS, Patient–Practitioner Orientation Scale.

Comparisons by academic year showed significant differences in four of the nine sharing items and four of the nine caring items. In all eight of these items, patient-centred attitudes were more prevalent among students in the fifth/sixth years as compared with students in the first year. Six of the eight items displayed a linear trend of increasing patient-centredness with increases in academic year. Overall, only two items displayed significant gender response differences, with more male patients favouring a provider-dominated style in item 4 (‘The most important part of the medical visit is the physical exam’), but more female patients favouring a provider-dominated style in item 8 (‘Many patients continue asking questions even if the doctor has already given an explanation’).

PPOS scoring

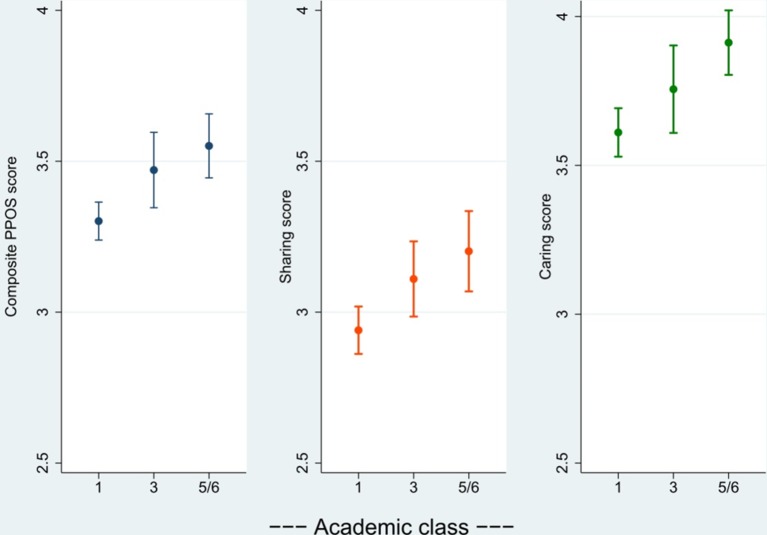

According to the scale’s original coding, mean PPOS score for the entire sample was 3.38 (SD=0.48), near the midpoint of the possible range (1-6). Mean score was slightly lower for the sharing subscale 3.04 (SD=0.60) and slightly higher for the caring subscale, 3.68 (SD=0.62). One-way ANOVAs comparing scores by academic year suggested significant difference in means for the entire scale (F=9.86, P<0.001), caring subscale (F=7.44; P<0.001) and sharing subscale (F=6.51; P=0.002). Subsequent Tukey-adjusted pairwise comparisons suggested significantly higher composite, sharing and caring scores in fifth/sixth year students as compared with first year students (figure 1). Third year students had higher significantly higher composite scores than first year students but otherwise did not significantly differ from either comparison groups.

Figure 1.

Mean scores with 95% CIs of the full PPOS and subscales in a sample of first, third and fifth/sixth year medical students in Bamako, Mali (n=430). PPOS, Patient–Practitioner Orientation Scale.

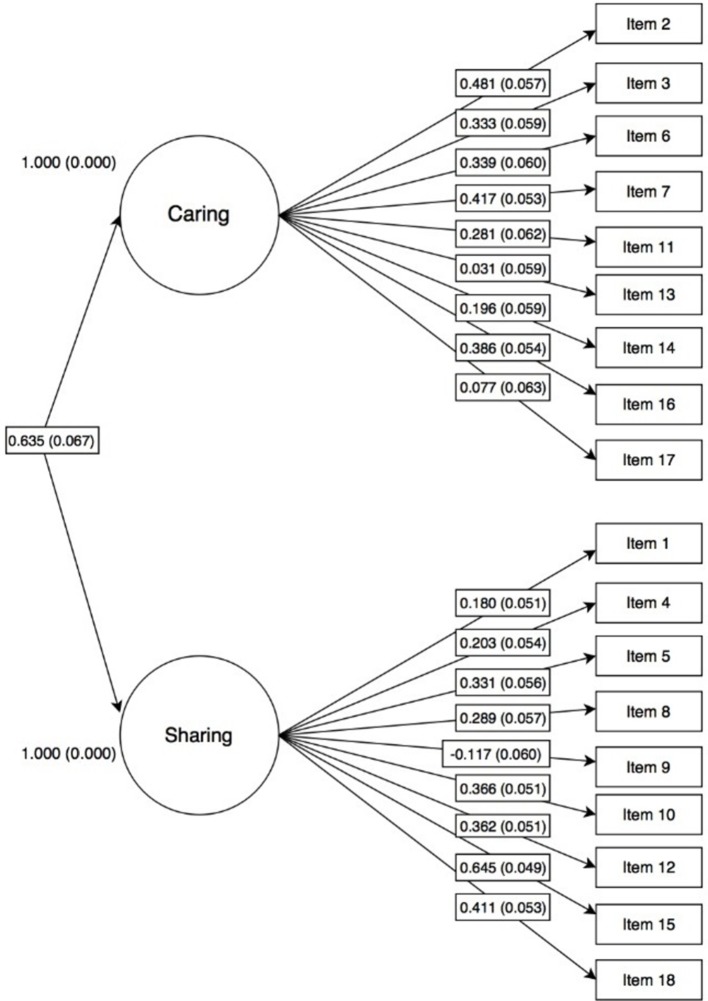

PPOS psychometrics

Cronbach’s alpha was low was for both the full scale (α=0.58), the caring subscale (α=0.37) and the sharing subscale (α=0.48). The CFA did not support the scale’s original two-factor structure, as illustrated by the poor item-factor loadings (most less than 0.4) in figure 2. While the χ2 test of model fit indicated an improved fit over the baseline model (χ2=773.0; df=153; P<0.001), other goodness-of-fit statistics were poor.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the Patient–Practitioner Orientation Scale in a sample of Malian medical students (n=430).

In the EFA, interitem correlations were generally low. Eigenvalues and parallel principal components analysis suggested a seven-factor model, but many individual items exhibited consistently low loadings for any given factor. We repeated the EFA with various iterations, dropping items with high uniqueness and poor loading, yet loadings remained low and we could not identify an interpretable factor structure with suitable goodness-of-fit statistics.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess patient-centred attitudes among medical students in West Africa. In most items in the ‘sharing’ subscale, responses indicated attitudes aligned with a ‘provider-dominant’ style of care versus a patient-centred one among the majority of students. In the ‘caring’ subscale, the majority responded favourably towards patient-centredness in some items but towards more ‘disease-centred’ or ‘low-caring’ attitudes in other items. In many items, patient-centred attitudes were more prevalent among students in higher academic years, but there were few differences by gender.

Attitudes favouring a more provider-dominated style of care, particularly in the 91% of students that agreed the patient must always be conscious that the doctor should lead the consultation, reveal a priority for future medical training in West Africa. Developing skills in sharing power can help providers increase patient trust and satisfaction, medication adherence and efficiency in consultations.4 8 Further, a prior study among patients with HIV in Mali suggests an unmet demand for shared power. In response to vignettes of patient–provider interactions, 40% of participants preferred ‘shared power’ over a provider-dominant style (36%) or no preference (24%).37 Those patients who expressed preference for ‘shared power’ versus ‘provider-dominant’ were also more likely to give low ratings of the quality of patient–provider communication at their care facility, suggesting disconnect between their preferred style and the style they experience.

Responses towards caring items also reveal target areas for training. For instance, students generally acknowledged the importance of the relationship with the patient and even the use of humour, but less than half agreed that a treatment plan must be concordant with a patient’s way of life to succeed. In our previous qualitative work, patients in Bamako appreciated friendliness and generally regarded their providers as friendly. However, they reported that providers did not often seek to understand and address their individual issues underlying poor medication adherence or missed appointments.38 Curricula that enhance skills in eliciting and supporting lifestyle and psychosocial influence on patient health may prepare future providers to better address issues like adherence.

Unlike previous studies, we found no evidence of lower patient-centredness in students of higher academic year. For some items, there appeared to be general trends towards higher patient-centredness with higher academic years. It is possible that there is a positive effect of training on patient-centred orientation, as students in advanced years are likely to have had extended clinical experiences similar to ’longitudinal integrated clerkships', which are replacing short-term rotations in some high-income settings due to their positive impact on developing patient-centredness in students.39 However, our findings could be explained by selection bias: typically, only one-fifth of first year students pass the exams permitting them to continue to subsequent training, resulting in a more selective student body in later academic years. While exams test clinical knowledge and not patient-centred attitudes or skills, it may be that students with more academic ability or commitment are also those who hold more patient-centred attitudes in items where this trend was observed. Selection bias could have also occurred in sampling, as fifth/sixth year students were sampled through social networks, and only first and third year students who attended class on the day of the survey were included.

According to the original PPOS scoring, our sample of Malian medical students was moderately oriented towards the caring aspect of patient-centredness and slightly less orientated towards the sharing aspect. Compared with previous studies, mean PPOS score (3.38) was higher (more patient centred) than the mean reported among South African medical students (2.24–2.65), comparable to students in Pakistan (3.40) and Greece (3.81–3.96) but lower than students in USA (4.57) and Brazil (4.66).17 18 21 25 40 However, scores from our study and the others we cite should be interpreted with caution, as internal consistency and construct validity measures were either inadequate or not reported in the publications.

Our internal consistency measures and factor analyses raise concerns about applying the PPOS outside of the high-income setting where it was developed. Among the many studies that have applied the PPOS in an international context, we only identified two that attempted to assess the structure and construct validity of the scale. In the previously cited South African study, Archer and colleagues reported poor internal consistency and no evidence of a latent factor structure in CFA or EFA.25 Pereira and colleagues concluded that the Brazilian adaptation of PPOS had acceptable internal consistency among physicians and medical students, however, the Cronbach’s alpha (α=0.605, similar to our 0.580) fell below the commonly accepted standard of 0.70 as an indication of adequate internal consistency.41 Similar to our findings, the factors extracted in the EFA conducted by Pereira and colleagues did not correspond with the original ‘caring’ and ‘sharing’ dimensions, and the fit statistics of the CFA were borderline acceptable.

The differences in structure and measurement properties we observed with the PPOS may be due to limitations of the measure itself or to differences in the way that the patient–provider relationship is conceptualised in this West African context. When examined against our qualitative findings, many of the original PPOS items did not directly reflect the values and experiences patients had expressed.38 Notably, the PPOS contains a number of items about the patient’s access to information, which rarely entered discussions with our patient participants in Bamako. The concept of patient-centredness may vary in different cultural settings42 and might ultimately be best defined by the patients themselves.43 For future research aiming to measure patient-centredness as a unified construct in sub-Saharan Africa, we recommend developing and validating contextually relevant scales based on careful selection of appropriate items from existing measures as well as new items derived through formative research. Barry and colleagues applied this method to develop a scale assessing the patient–provider relationship in prevention of mother-to-child transmission facilities in South Africa; that scale demonstrated high internal consistency and strong factor loadings.44

Our findings should be considered in light of the following limitations. First, our cross-sectional data limits us from drawing any conclusions about the causal effect of medical training on attitudes. Second, a large proportion of students were not present on campus during survey administration and surveys were distributed through social networks for fifth and sixth year students. These factors may have resulted in selection bias (students with more positive attitudes may have been more likely to be selected). The more informal social network distribution limited us from calculating a valid overall response rate. A further limitation is that even after multiple rounds of pretesting, it is possible that some questions may not have been interpreted as intended by all participants. A more systematic approach to the translation of items, like the Delphi method applied by Pereira and colleagues,45 may have helped improve the translation quality. Additionally, though we conducted this study at one of the major medical training facilities in West Africa, the fact it was conducted at only one institution may limit generalisability of findings. Finally, the PPOS measures attitudes, which do not always translate into the provider behaviours that relate to better care outcomes. While attitudes and orientation are important, measuring specific communication skills in providers (as well as their effect on patient outcomes) should be incorporated into educational efforts that aim to promote better patient–provider relationships.22

As sub-Saharan Africa faces the increasingly multifaceted public health challenges of the 21st century, the need for effective patient–provider relationships becomes more critical than ever. Our findings suggest that more work is needed to ensure that medical students in West Africa develop and sustain positive attitudes towards patient-centred care. It is time for a concerted effort among medical schools to pilot and implement curricula that fosters a patient-centred orientation. Our findings—in the context of the patient literature from the region—suggest focus on developing effective skills and favourable attitudes towards power sharing and addressing lifestyle factors. A movement towards patient-centred care, however, cannot be successful with curricula changes alone. First, as our study reveals, evaluation of any effort to increase patient-centred attitudes and practice will require improved measurement tools based on terminology, concepts and clinical experiences relevant to local settings. Second, systemic changes in both local health systems and the international public health environment are needed to ensure that patient-centredness is fully valued, enabled and supported.16 These efforts may include transforming supervision mechanisms to model shared power (vs reinforce authoritarianism), incentivising and supporting providers to live in and build long-term relationships with hard-to-reach communities and fully shifting vertical disease-control programmes into integrated primary care systems that measure and reward patient-centred outcomes.16 These multilevel changes could create an enabling environment to help raise the suboptimal attitudes we observed among students and put patient-centred care into practice, potentially yielding enormous benefits to patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Nièlè Hawa Diarra for her assistance with translation, Danait Yemane for conducting pilot testing and survey revisions, Hamza Dakao and Madeleine Beebe for executing data collection, Gina Hurley and Katie Hurley for assistance with data entry and Dr Nicole Warren for comments on early versions of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: EAH led the design of the work, as well as the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. SD contributed to the design of the work, the acquisition and interpretation of data, and important intellectual revisions to the manuscript. CEK, PJW, DLR and SAH contributed to the design of the work, the interpretation of data and important intellectual revisions to the manuscript. SMM contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data as well as important intellectual revisions to the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health through the Ruth L Kirchstein National Research Service Award (F31MH106398) and the US Department of Education through the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Fellowship (P022A140064).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: IRB at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Ethics Committee at University of Sciences, Technologies and Techniques of Bamako.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Possibility for data sharing can be discussed with the corresponding author.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Regional office for Africa. The health of the people: the African regional health report. Brazzaville: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Health workforce 2030: towards a global strategy on human resources for health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gerteis M. Through the patient’s eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, et al. . Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 1995;40:903–18. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care 2009;47:826–34. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flickinger TE, Saha S, Moore RD, et al. . Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63:362–6. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318295b86a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. . The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract 2000;49:796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roter DL, Stewart M, Putnam SM, et al. . Communication patterns of primary care physicians. JAMA 1997;277:350–6. 10.1001/jama.1997.03540280088045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abdel-Tawab N, Roter D. The relevance of client-centered communication to family planning settings in developing countries: lessons from the Egyptian experience. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:1357–68. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00101-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Watt MH, Maman S, Golin CE, et al. . Factors associated with self-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a Tanzanian setting. AIDS Care 2010;22:381–9. 10.1080/09540120903193708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lau SR, Christensen ST, Andreasen JT. Patients’ preferences for patient-centered communication: a survey from an outpatient department in rural Sierra Leone. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93:312–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larson E, Vail D, Mbaruku GM, et al. . Moving toward patient-centered care in Africa: a discrete choice experiment of preferences for delivery care among 3,003 Tanzanian women. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135621 10.1371/journal.pone.0135621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pfeiffer A, Noden BH, Walker ZA, et al. . General population and medical student perceptions of good and bad doctors in Mozambique. Educ Health 2011;24:387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abiola T, Udofia O, Abdullahi AT. Patient-doctor relationship: the practice orientation of doctors in Kano. Niger J Clin Pract 2014;17:241–7. 10.4103/1119-3077.127567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jaffré Y. Une médecine inhospitalière: les difficiles relations entre soignants et soignés dans cinq capitales d’Afrique de l’Ouest. Karthara Editions, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Man J, Mayega RW, Sarkar N, et al. . Patient-centered care and people-centered health systems in sub-Saharan Africa: why so little of something so badly needed? Int J Pers Cent Med 2016;6:162–73. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsimtsiou Z, Kerasidou O, Efstathiou N, et al. . Medical students’ attitudes toward patient-centred care: a longitudinal survey. Med Educ 2007;41:146–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02668.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ribeiro MM, Krupat E, Amaral CF. Brazilian medical students’ attitudes towards patient-centered care. Med Teach 2007;29:e204–e208. 10.1080/01421590701543133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsimtsiou Z, Kirana PS, Hatzichristou D. Determinants of patients’ attitudes toward patient-centered care: a cross-sectional study in Greece. Patient Educ Couns 2014;97:391–5. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. . An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Med Educ 2004;38:934–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01911.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haidet P, Dains JE, Paterniti DA, et al. . Medical student attitudes toward the doctor-patient relationship. Med Educ 2002;36:568–74. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01233.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff 2010;29:1310–8. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maggio LA, Tannery NH, Chen HC, et al. . Evidence-based medicine training in undergraduate medical education: a review and critique of the literature published 2006-2011. Acad Med 2013;88:1022–8. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182951959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Greysen SR, Dovlo D, Olapade-Olaopa EO, et al. . Medical education in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. Med Educ 2011;45:973–86. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Archer E, Bezuidenhout J, Kidd M, et al. . Making use of an existing questionnaire to measure patient-centred attitudes in undergraduate medical students: a case study. Afr J Health Prof Educ 2014;6:150 10.7196/ajhpe.351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krupat E, Rosenkranz SL, Yeager CM, et al. . The practice orientations of physicians and patients: the effect of doctor-patient congruence on satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns 2000;39:49–59. 10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00090-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van der Merwe LJ, van Zyl GJ, St Clair Gibson A, et al. . South African medical schools: current state of selection criteria and medical students’ demographic profile. S Afr Med J 2015;106:76–81. 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i1.9913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lodenstein E, Dao D. Devolution and human resources in primary healthcare in rural Mali. Hum Resour Health 2011;9:15 10.1186/1478-4491-9-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tunçalp Ö, Fall IS, Phillips SJ, et al. . Conflict, displacement and sexual and reproductive health services in Mali: analysis of 2013 health resources availability mapping system (HeRAMS) survey. Confl Health 2015;9:28 10.1186/s13031-015-0051-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shaw WS, Woiszwillo MJ, Krupat E. Further validation of the Patient-Practitioner Orientation Scale (PPOS) from recorded visits for back pain. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89:288–91. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res 2003;12:229–38. 10.1023/A:1023254226592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPLUS Version 6.11, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yates A. Multivariate exploratory data analysis: a perspective on exploratory factor analysis. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hu Li‐tze, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assessment, Res Eval 2005;10:173–8. doi:10.1.1.110.9154 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hurley EA, Harvey SA, Keita M, et al. . Patient-provider communication styles in HIV treatment programs in Bamako, Mali: A mixed-methods study to define dimensions and measure patient preferences. SSM Popul Health 2017;3:539–48. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hurley EA, Harvey SA, Winch PJ, et al. . The Role of Patient-Provider Communication in Engagement and Re-engagement in HIV Treatment in Bamako, Mali: A Qualitative Study. J Health Commun 2017:1–15. 10.1080/10810730.2017.1417513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walters L, Greenhill J, Richards J, et al. . Outcomes of longitudinal integrated clinical placements for students, clinicians and society. Med Educ 2012;46:1028–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ahmad W, Krupat E, Asma Y, et al. . Attitudes of medical students in Lahore, Pakistan towards the doctor-patient relationship. PeerJ 2015;3:e1050 10.7717/peerj.1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ 2011;2:53–5. 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mole TB, Begum H, Cooper-Moss N, et al. . Limits of ‘patient-centredness’: valuing contextually specific communication patterns. Med Educ 2016;50:359–69. 10.1111/medu.12946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Berwick DM. What ‘patient-centered’ should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff 2009;28:w555–65. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barry OM, Bergh AM, Makin JD, et al. . Development of a measure of the patient-provider relationship in antenatal care and its importance in PMTCT. AIDS Care 2012;24:680–6. 10.1080/09540121.2011.630369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pereira CM, Amaral CF, Ribeiro MM, et al. . Cross-cultural validation of the Patient-Practitioner Orientation Scale (PPOS). Patient Educ Couns 2013;91:37–43. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.