Abstract

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity has increased significantly in the last three decades and became an important public health concern. Evidence of weight status variability at the neighbourhood level has led researchers to look more precisely at the characteristics of local geographic areas that might influence energy balance related behaviours, giving rise to the field of the ‘neighbourhood effect’ in public health research. Among an abundant literature about neighbourhood effects and obesity, we propose a protocol for a scoping review that will aim at determining how temporal measurements of residential neighbourhood exposure, individual covariates and weight outcome are integrated in longitudinal designs.

Methods and analysis

A list of relevant citations will be obtained through a comprehensive systematic database search in Pubmed, Web of Science and Embase. The search strategy will be designed using a broad definition of neighbourhood to take into account the heterogeneity of this concept in research. Two investigators will screen titles, abstracts and entire publications using predetermined eligibility criteria yielding a list of selected publications. Data from the publications included in the scoping review will be charted according to bibliographic information, study population, exposure, outcomes and results.

Discussion and conclusion

To our knowledge, our protocol will yield the first scoping review regarding longitudinal designs of neighbourhood effect on obesity. Describing how longitudinal designs include temporal measurements of exposure, covariates and outcome is a necessary step in the quest to determine if or which contextual characteristics are likely to be involved in the development of obesity. Such information would bring new knowledge to complement current aetiological investigations and would contribute to enhancing resource allocation strategies for stakeholders in developing relevant interventions to prevent obesity and its negative impacts.

Keywords: Scoping review, obesity, neighbourhood effect, longitudinal design, residential history

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, the first review of longitudinal designs of neighbourhood effect studies on obesity.

Includes a comprehensive research strategy that takes into account the complexity of neighbourhood research.

The descriptive nature of a scoping review excludes a quantitative analysis of the results.

Not including children in this scoping review limits its scope but increases the homogeneity of the results.

Introduction

Rationale

With an increasing prevalence in the last three decades, obesity has become an important public health concern in most countries of the world. Individuals with obesity are more at risk of developing certain conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancer. The loss of productivity and costs associated with the treatment of obesity-related health problems are taking a toll on many developed and developing countries.1 2

In an effort to develop more effective obesity prevention, researchers have looked at the various causes, both proximal and distal, of the obesity epidemic.3

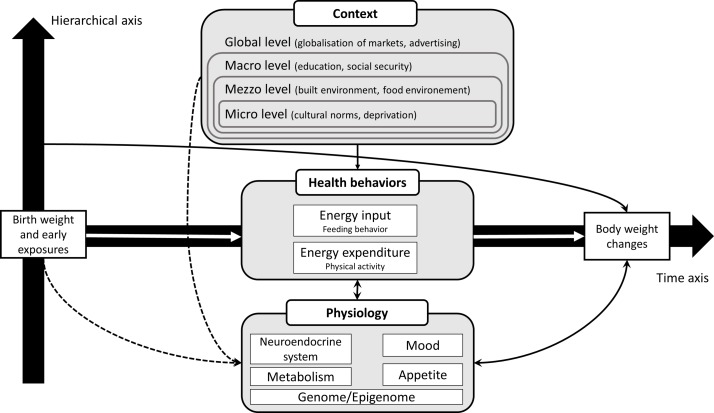

Figure 1 shows a complex influence system on obesity proposed by Glass and McAtee4 on which the scientific community has reached a certain degree of consensus, although the system is sometimes depicted in its more or less complicated form.5–7 At the centre of this model lies a largely accepted premise: an increase in body fatness is the result of an imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure.7 Yet, causal pathways underlying the energy balance are much more complex and many researchers suggest that interventions focused on re-establishing the proper balance by individual control of their diet and physical activity has limited effects.7 8

Figure 1.

Multilevel influences on obesity. Although presenting a much simplified illustration of the complexity of the causal pathways that might have an impact on weight status, this conceptual model displays in a very effective way the hierarchical structure of influences on health behaviours linked to obesity, where ‘context’ includes levels of organisation above the individual and ‘physiology’ comprises factors from various biological systems inside the individual. The longitudinal perspective of weight change is depicted as a horizontal axis where the context–behaviour–physiology nexus changes as time passes. Also shown are the hypothesised socioeconomic (education, deprivation, norms and so on) and physical (built environment, foodscape and so on) contextual influences on obesity (modified from Glass and McAtee).4

For example, public health professionals, although preoccupied by population health issues, have historically focused on the personal responsibility of individuals for their weight loss, leading to numerous mass media campaigns on healthy eating and physical activity. As a result, collective knowledge on favourably perceived or ‘healthy’ behaviour was increased, but the effect on body weight was limited.9

At the individual level, dieticians, exercise specialists and healthcare professionals also work on behaviour modification to help persons with overweight or obesity achieve weight loss. And although short-term weight loss is generally obtained when patients are offered sufficient support, maintenance of weight loss is much more difficult and weight is often regained over a 5-year time lapse.10 11

At the physiological level, bariatric surgeons acting directly on digestive mechanisms have had successful results, with an average excess weight loss up to 70%, depending on the procedure used.12 But as with dieting, long-term weight loss maintenance is uncertain.13–16

Acknowledging these difficulties leads to an argument that the modern world has a strong obesogenic influence and that personal control may not be enough to prevent weight grain through the life course. This is why the obesity research community has engaged in studies aimed at finding which factors above the individual level have an impact on obesity. Many contextual characteristics, illustrated in figure 1, have been theorised to have an impact on behaviours that influence either energy intake, energy expenditure or both. A rich body of literature explored these contextual forces going from the micro to the local and the global scale: family behaviours, social norms, foodscape, built environment, education, market globalisation and so on.3 4

Researchers have taken particular interest to weight status variability at the local level and are now looking more precisely at the characteristics of smaller residential geographic areas.17 18 This so-called ‘neighbourhood effect’ research field examines whether neighbourhoods might influence weight gain.19–22 From a socioeconomic perspective, a literature review from McLaren23 reports a negative relationship between contextual indicators of socioeconomic status and body mass index (BMI), for women and for both sexes combined in developed countries. Although the same type of studies19 24–28 exists for physical environments and their influence on body mass, the conclusions tend to show less significant relationships. Urban sprawl (positive) and land use mix (negative) being the only indicators shown to have a relatively consistent and statistically significant association with an increased BMI in recently published reviews.25 27 29

The lack of strong associations in neighbourhood effect studies can be explained, in part, by the complexity of the obesity system of influence and by methodological obstacles.26 Among the methodological obstacles is the challenge of conducting randomised experiments which are generally recommended to infer causality between exposure and outcomes.30 However, a social randomised experiment controlling for the place where one lives would be particularly complex to realise and would raise important ethical concerns. Therefore, the vast majority of studies looking into neighbourhood influences on obesity are observational and have cross-sectional designs, measuring exposure to residential areas and body weight at only one point in time. These studies omit to take into account the temporal perspective of neighbourhood effect which include residential history, changes in the neighbourhood characteristics over time and residential self-selection.29 31 32 These important limitations are constantly reported by researchers and curb the capacity to infer which interventions would have the greatest effect on controlling the obesity epidemic. In recent literature, specific calls for comparable longitudinal or experimental data have been made to measure more precisely neighbourhood effects on weight gain.29 32–35

An increasing number of research teams are presenting upgraded study designs, moving off cross-sectional studies that are limited to observations at one particular point in time. However, there is still no review providing information on existing longitudinal studies. Mapping the literature regarding the neighbourhood effect on obesity, where contextual exposure, individual covariates and weight outcome are measured at different points in time, whether in experimental or observational studies, would be the next logical step. We are thus presenting a scoping review protocol with the objective of looking more specifically at longitudinal studies of neighbourhood effects on obesity, the specific study designs employed and their results.

The scoping review approach was chosen for this literature review protocol since the broad number of study designs makes it difficult, and hardly relevant, to sum and compare results quantitatively, a necessary step for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. The framework of this review will follow the five-step framework proposed by Arksey and O Malley for scoping reviews in a process of ‘summarizing a range of evidence in order to convey the breadth and depth of a field’.36 37

Research question and objectives

Among an abundant literature about neighbourhood effects on obesity, this scoping review will aim at drawing an up-to-date portrait using the following research question: How are the temporal measurements of contextual exposure, individual covariates and weight outcome integrated into studies that explore the impacts of physical and socioeconomic neighbourhood contexts on adult weight status? In this review, a longitudinal design will be considered in its broadest meaning, including any study having contextual exposure and/or weight outcome and/or covariates measured at more than one point in time.38 39

The specific objectives of this review are: to detail the number of studies investigating longitudinal neighbourhood effects on weight status; to describe and classify the study designs used to investigate longitudinal neighbourhood effects on weight status; to describe and classify the type of analysis used to take into account the temporal dimension; to carry out a qualitative summary of results.

According to the main findings, recommendations for future research on neighbourhood effects will be proposed.

Methods and analysis

Identifying relevant studies: transitioning from the conceptual model to keywords

Two major difficulties arise when trying to identify neighbourhood effect studies (1) defining what a neighbourhood is and (2) identifying measures of neighbourhood characteristics. To settle those problems, a very broad definition of neighbourhood will be used in the search strategy, going from ‘residence characteristics’ to ‘environment' and neighbourhood characteristics, going from ‘sociological factor’ to ‘urban form’. As a result of this far-reaching search strategy, the relevant citations list will likely include an important number of citations that will not meet the eligibility criteria and that will have to be screened manually.

Table 1 displays the eligibility criteria that are derived from the conceptual model shown in figure 1 with a specific interest in the neighbourhood context.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for selection of publications (modified from the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework)46

| Criteria | Description |

| Population | The target population of this study will be adults between 18 and 65 years of age, as weight changes are not always homogeneous during both childhood and old age. Multiple (at least two) measurements are required in a longitudinal study and here, at least two measurements of weight and neighbourhood characteristics must have been performed during adult age (18–65 years old), other measurements could be done in childhood, youth or old age. |

| Exposure | Exposure will be measured by any indicator of neighbourhood characteristic, where neighbourhood is defined as an administratively delimited geographic area enclosing the participant’s residence, a buffer delimited area around the participant’s residence or a perceived area delimited by the participant. The geographic area will have to be defined at the neighbourhood level, which is smaller than a city or municipal area. |

| Outcome | Many outcomes of neighbourhood effects on obesity-related behaviours can be measured (fruits and vegetable consumption, leisure time physical activity, transport physical activity and so on), but to ease the review process and facilitate design comparison, only studies with body composition indicators will be selected. Eligible studies will be those reporting measured or declared weight status as total body weight, body mass index, waist circumference, waist/hip ratio and/or skin fold thickness. Obesity is often used as a general term to refer to weight gain or overweight in the literature, although it has a very specific clinical definition (BMI>30). In this review, any studies considering body composition as an outcome will be included, whether it categorises weight status or not. |

| Study design | Selected studies will include a longitudinal perspective in the measurement of the exposure and/or outcome and/or covariates. For example, studies with the following design could be considered as longitudinal: experimental or quasi-experimental schemes, where participants are exposed to different living environments over time; case-control studies and cohort studies, where exposure is measured at different points in time or is classified as a pattern over time. Cross-sectional studies will be systematically excluded. Study designs that focus only on life-course changes in weight status (or of the secondary outcomes) without measuring contextual exposure will not be included in this review. |

Studies regarding neighbourhood effects on health can be published in a large spectrum of scientific journals covering various disciplines: epidemiology, public health, economy, urban planning and so on. Such multidisciplinary perspective requires that a variety of scientific citation indexes be explored. The electronic databases used for this scoping review will include: Medline (PubMed), Embase and Web of Science. Only English peer-reviewed literature published in a referenced journal will be considered. No limit on dates of coverage is yet imposed.

The selected databases will be screened using a comprehensive search strategy. A sample search terms combination for the PubMed database is presented in table 2. Strategies for other databases will be adapted in a way to be as close as possible to the PubMed strategy. The search term combination is fragmented into five keyword combinations to match the components of the study question as closely as possible. They take into account the desired outcomes, the numerous contextual level indicators which may be used to measure neighbourhood exposure and the longitudinal designs that are the focus of this scoping review.

Table 2.

Sample search strategy (PubMed)

| Terms | Type |

| Outcome | |

| Obesity | MeSH:noexp, TIAB |

| Obesity, morbid | MeSH |

| Body mass index | MeSH, TIAB |

| Body mass index | TIAB |

| Overweight | MeSH:noexp, TIAB |

| Weight | TIAB |

| Adiposity | TIAB |

| Longitudinal design | |

| Cohort studies | MeSH |

| Prospective studies | MeSH |

| Cohort* | TIAB |

| Follow-up | TIAB |

| Longitudinal | TIAB |

| Retrospective | TIAB |

| Life course | TIAB |

| Randomised | TIAB |

| Change | TIAB |

| Experimental | TIAB |

| History | TIAB |

| Geographic context | |

| Environment | MeSH:noexp |

| Residence characteristics | MeSH:noexp |

| Neighborhood* | TIAB |

| Neighbourhood* | TIAB |

| Catchment area (health) | MeSH |

| Residential | TIAB |

| Residence | TIAB |

| Context | TIAB |

| Composition | TIAB |

| Urban | TIAB |

| Social environment exposure | |

| Sociological factors | MeSH:noexp, TIAB |

| Socioeconomic factors | MeSH |

| Low income | TIAB |

| Education | TIAB |

| Poverty | TIAB |

| Socioeconomic | TIAB |

| Income | TIAB |

| Social conditions | TIAB |

| Physical environment exposure | |

| Environment design | MeSH |

| City planning | MeSH, TIAB |

| Food service | MeSH |

| Urban planning | TIAB |

| Built environment | TIAB |

| Physical environment | TIAB |

| Urban form | TIAB |

| Obesogenic environment | TIAB |

‘Type’ refers to the tags complementing search terms in queries. ‘MeSH’ (Medical Subject Heading) terms will be searched in the controlled vocabulary assigned by US National Library of medicine to index scientific articles in its database. ‘MeSH:noexp’ terms have the same function as MeSH, except that the search will be limited to the exact term not including subordinate terms generally linked to MeSH terms. ‘TIAB’ terms will be searched in the title and abstract of the citations. The asterik (*) following some terms is used to find all terms that have a common beginning.

The search components will be articulated as follows:

Outcome terms AND longitudinal design terms AND (geographic context terms AND (social environment exposure terms OR physical environment exposure terms))

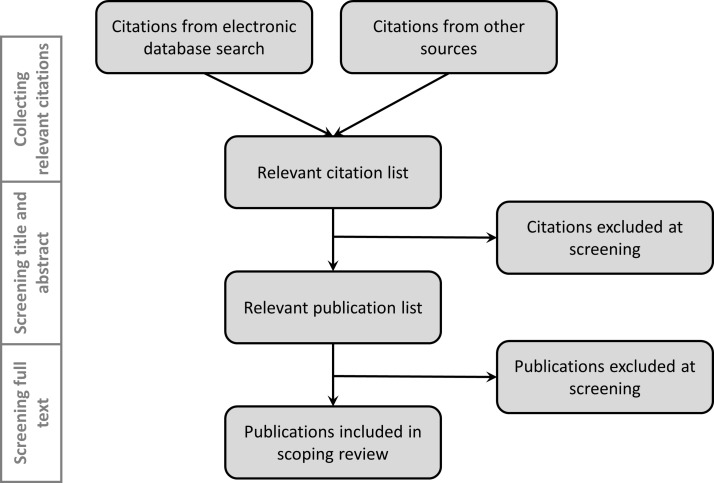

Study selection

Results from the search strategy will yield an extended list of scientific citations that are related to the research question closely or remotely. This list, managed in a Microsoft Access 15.0.2013 database, will be completed with citations that fit the eligibility criteria referenced in relevant publications but that did not turn up in the systematic search strategy. This is the first step of a selection process that will lead to a formal list of citations to be included in the scoping review. The steps involved in selecting the studies are outlined in figure 2. After collecting relevant citations through the searches of the three key databases, the next step involves screening titles and abstracts for possible eligibility. Selected studies will have to meet all the criteria specified in table 1 to be included. The screening process will be performed separately by two investigators. Both investigators will start the process by conducting a pilot trial on the first 5% of the relevant citation list to verify screening uniformity and to refine the screening strategy. The completion of the second step will yield a shorter list of relevant publications. In a third step of the selection, reviewers will assess eligibility by reading the full manuscript of the publications on the short list. Ultimately, final inclusion of the publications will be discussed by the two reviewers and any disagreement on the inclusion or exclusion will be resolved by consensus.

Figure 2.

Suggested flowchart to identify publications that will be included in the scoping review from citations issued by the database search (based on Khan).44

Charting the data

Because publications focusing on neighbourhood effects and body weight come from a wide variety of research areas, the data extraction phase will aim at systematically recording sufficient relevant information on study designs or results to enable drawing conclusions on the variety of the study designs screened. Information will be extracted from the studies using a piloting form with a priori selected variables (table 3). The piloting form will be applied for the charting of the first 10% of the included publications. In the light of this first round, variables could be added or eliminated to produce a working version of the chart. Since the purpose of this scoping review is to take into account the sum of the literature on longitudinal neighbourhood effect on obesity and to address the multiplicity of designs, complementary notes on any particularity of the studies will be recorded.

Table 3.

A priori selected variables to be extracted from the publications included in the scoping review

| Study characteristics | Variables |

| Bibliographic | Title |

| Author | |

| Year | |

| Journal name | |

| Study population | Data provenance (source, year) |

| Specific characteristic of chosen population (age, sex, country, socioeconomic status) | |

| Individual covariates used for model adjustment | |

| Length of follow-up | |

| Exposure | Data provenance (source, year) |

| Contextual exposure | |

| Geographic area measurement | |

| Number and time of measurement | |

| Outcomes | Primary (obesity indicators) |

| Secondary (energy expenditure, energy consumption) | |

| Number and time of measurement | |

| Analysis | Type of statistical model used |

| Results | Important results (eg, sense, strength and significance of statistical association) |

| Potential biases |

Although quality assessment and identification of bias are not necessary requirements of scoping reviews,36 some authors suggest that they could be relevant to identify gaps in the evidence base.40 The identification of potential bias is not included in this review to assess the quality of the study’s results per se but with the purpose of evaluating the strengths and weaknesses associated with the various longitudinal designs. In this perspective, a simple tool, the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tool, was chosen to perform the quality assessment.41

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Following the selection process and data extraction illustrated in figure 2 and table 3, a narrative account of the literature will be performed. This section of the scoping review will be divided into two parts.36 First, a simple numerical analysis of the number, nature and distribution of the variables extracted from the publications included in the review will be performed. This exercise will aim at drawing up a detailed picture of the literature concerned with the longitudinal impact of neighbourhood characteristics on weight. Second, the studies will be classified according to their designs (experimental, case-control, cohort and so on). For each group of studies, results will be summarised and possible bias will be identified.

Discussion and dissemination

Consistent with current research related to neighbourhood impacts on weight, this scoping review will aim at drawing a general portrait of the publications using longitudinal designs to include temporal measurements of contextual exposure, individual covariates and weight outcome.

In light of the importance of the global obesity epidemic, having a better understanding of neighbourhood impacts on obesity is crucial. This scoping review will address a current need increasingly mentioned in the literature and will orient researchers in developing high quality longitudinal study designs and data collection platforms in order to improve our understanding of the relationship between neighbourhood exposure and weight.

Beyond the scientific and methodological benefits of this study, it is also very relevant in the current practice of urban design. For over 30 years, urban planners have been asked to create supportive environments for obesity prevention and to facilitate individual’s health lifestyle.42 43 But the complexity of the obesity system limits the possibility to make informed evidence-based decisions. Not knowing how or if contextual exposures have an impact on weight gain could lead to misguided neighbourhood design. Moving a step further on the path of neighbourhood effects research by describing longitudinal study designs, might, eventually lead to more significant results and contribute to disentangling the so-called neighbourhood effect or clarify if contextual influences really do have a role on weight gain. And although the route towards more causal evidence of neighbourhood effect on obesity is not the only way to inform public health policies, seeking to improve longitudinal studies could be part of a better planning of interventions against the obesity epidemic.

Scoping reviews, in their nature, are not intended to synthesise and aggregate results, as their topics are generally too heterogeneous to perform such analysis. Therefore, one limitation of this review will be the scope of its results, which will be limited to a descriptive analysis. Although no new quantitative evidence will emerge from this research, its conclusion could suggest the necessity and the feasibility of an extensive systematic review which, in its time, could generate new and more precise information.

The weight status of a human being has much variability over its life course with some periods and determinants being more critical to potential obesity development.44 45 Therefore, for uniformity reasons, and although some authors have suggested that neighbourhood effects are stronger when considering trajectories that include childhood, we have decided to limit this scoping review to the measurement of weight change in adults.22 This restriction may limit the number of publications included and reduce the number of longitudinal designs to consider, but will certainly reduce the heterogeneity among the selected studies and facilitate the comparability between them. Such an approach allows for a future systematic literature review with greater focus on those relationships. Performing a scoping review for longitudinal designs of research on neighbourhood effects on children weight status could be considered as a research project on its own, taking into consideration that children have different weight gain and activity patterns than those of adults.

The results of this scoping review will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal and the findings will be the focus of presentations at scientific conferences. No approval from an ethics committee was sought for this study as it will involve already published data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Frédérick Bergeron from Université Laval for his valuable assistance on the development of the bibliographic research strategy.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept, design and drafting of the manuscript: LL, AL. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: AL, OW, AT, LB.

Funding: This project was supported by the Evaluation Platform on Obesity Prevention and the Fondation IUCPQ (3207). AL is partially funded by the Québec’s Funds for health Research (FQS109600). LB and AT received grant funding from Johnson & Johnson Medical Companies for research on bariatric surgery not related to the present review.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Müller-Riemenschneider F, Reinhold T, von Schulzendorff A, et al. Health economic burden of obesity-an international perspective. Obesity epidemiology: from aetiology to public health. 74, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kumanyika S, Jeffery RW, Morabia A, et al. Obesity prevention: the case for action. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:425–36. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envisioning the future. Soc Sci Med 2006;62:1650–71. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Butland B, Jebb S, Kopelman P, et al. Foresight. Tackling obesities: future choices. Project report: UK Government’s Foresight Programme, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumanyika SK, Parker L, Sim LJ. Bridging the evidence gap in obesity prevention: a framework to inform decision making: National Academies Press, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang TT, Drewnosksi A, Kumanyika S, et al. A systems-oriented multilevel framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Prev Chronic Dis 2009;6:10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011;378:804–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crawford D. Obesity epidemiology. USA: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Middleton KM, Patidar SM, Perri MG. The impact of extended care on the long-term maintenance of weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2012;13:509–17. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00972.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mann T, Tomiyama AJ, Westling E, et al. Medicare’s search for effective obesity treatments: diets are not the answer. Am Psychol 2007;62:220–33. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;292:1724–37. 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Moore RH, et al. Preoperative eating behavior, postoperative dietary adherence, and weight loss after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2008;4:640–6. 10.1016/j.soard.2008.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Magro DO, Geloneze B, Delfini R, et al. Long-term weight regain after gastric bypass: a 5-year prospective study. Obes Surg 2008;18:648–51. 10.1007/s11695-007-9265-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karmali S, Brar B, Shi X, et al. Weight recidivism post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg 2013;23:1922–33. 10.1007/s11695-013-1070-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones L, Cleator J, Yorke J. Maintaining weight loss after bariatric surgery: when the spectator role is no longer enough. Clin Obes 2016;6:249–58. 10.1111/cob.12152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eid J, Overman HG, Puga D, et al. Fat city: Questioning the relationship between urban sprawl and obesity. J Urban Econ 2008;63:385–404. 10.1016/j.jue.2007.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moon G, Quarendon G, Barnard S, et al. Fat nation: deciphering the distinctive geographies of obesity in England. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:20–31. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Booth KM, Pinkston MM, Poston WSC. Obesity and the built environment. J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105:110–7. 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oakes JM. The (mis)estimation of neighborhood effects: causal inference for a practicable social epidemiology. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:1929–52. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Diez Roux AV. Estimating neighborhood health effects: the challenges of causal inference in a complex world. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:1953–60. 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00414-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glass TA, Bilal U. Are neighborhoods causal? Complications arising from the ’stickiness' of ZNA. Soc Sci Med 2016;166:244–53. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:29–48. 10.1093/epirev/mxm001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, et al. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:129–43. 10.1093/epirev/mxm009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Feng J, Glass TA, Curriero FC, et al. The built environment and obesity: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Health Place 2010;16:175–90. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ding D, Gebel K. Built environment, physical activity, and obesity: what have we learned from reviewing the literature? Health Place 2012;18:100–5. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mackenbach JD, Rutter H, Compernolle S, et al. Obesogenic environments: a systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health 2014;14:233 10.1186/1471-2458-14-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leal C, Chaix B. The influence of geographic life environments on cardiometabolic risk factors: a systematic review, a methodological assessment and a research agenda. Obes Rev 2011;12:217–30. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00726.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Garfinkel-Castro A, Kim K, Hamidi S, et al. The Built Environment and Obesity Ahima RS, ed Metabolic Syndrome: A Comprehensive Textbook, 2016:275–86. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern epidemiology: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins,, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Merlo J. Contextual influences on the individual life course: building a research framework for social epidemiology. Psychosocial Intervention 2011;20:109–18. 10.5093/in2011v20n1a9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wheeler DC, Calder CA. Sociospatial Epidemiology: Residential History Analysis : Lawson AB, Banerjee S, Haining RP, Handbook of Spatial Epidemiology: CRC Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Creatore MI, Glazier RH, Moineddin R, et al. Association of Neighborhood Walkability With Change in Overweight, Obesity, and Diabetes. JAMA 2016;315:2211–20. 10.1001/jama.2016.5898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chiu M, Shah BR, Maclagan LC, et al. Walk Score and the prevalence of utilitarian walking and obesity amongst Ontario adults: A cross-sectional study. Health Rep 2015;26:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sallis JF, Cerin E, Conway TL, et al. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2016;387:2207–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01284-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:285–93. 10.1093/intjepid/31.2.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Naess O, Leyland AH. Analysing the effect of area of residence over the life course in multilevel epidemiology. Scand J Public Health 2010;38:119–26. 10.1177/1403494810384646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, et al. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 2014;5:371–85. 10.1002/jrsm.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical appraisal tools - JBI. 2017. http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html

- 42. World Health Organization. Ottawa charter for health promotion, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization. Shanghai declaration on promoting health in the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44. Ziyab AH, Karmaus W, Kurukulaaratchy RJ, et al. Developmental trajectories of Body Mass Index from infancy to 18 years of age: prenatal determinants and health consequences. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:934–41. 10.1136/jech-2014-203808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, et al. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club 1995;123:A12–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.