Abstract

Yoga is underutilized among racial/ethnic minorities and low-income populations. To enhance participation among these demographic groups and to inform a future clinical trial, we conducted a qualitative formative investigation, informed by the Social Contextual Model of health behavior change, to identify barriers and facilitators to yoga that could impact study participation. We recruited twenty-four racially/ethnically diverse adults, with and without prior yoga experience, from a low-income, urban housing community to participate in either an individual interview or focus group. A thematic data analysis approach was employed. Barriers to yoga engagement included the perception that yoga lacks physicality and weight loss benefits, fear of injury, lack of ability/self-efficacy to perform the practices, preference for other physical activities, and scheduling difficulties. Facilitators of yoga engagement included a quality yoga instructor who provides individualized instruction, beginner level classes, and promotional messaging that highlights the potential benefits of yoga, such as stress reduction.

Keywords: yoga, qualitative, racial/ethnic minority, low-income, community-based, marginalized populations

1. Introduction

Yoga participation among adults in the United States has grown significantly over the past decade, from 5.1% in 2002 to 9.5% in 2012 (Clarke et al., 2015). Yoga is most commonly practiced among non-Hispanic white, college educated, female, young to middle aged adults (Clarke et al., 2015; Markula, 2014). Individuals of higher socio-economic status (SES) also are more likely than other groups to use integrative medicine therapies including yoga (Bertisch et al., 2009; Bishop & Lewith, 2010; Su & Li, 2011); in 2016 an estimated $16.8 billion was spent on yoga classes and related supplies in the United States alone (Yoga Journal, 2016).

Scientific investigations of the health benefits of yoga have increased over the past twenty years (Cramer et al., 2014; Jeter et al., 2015; Khalsa et al., 2016; Field, 2016). Overall, research suggests that yoga can offer physical and mental health benefits (Bussing et al., 2012; Khalsa et al., 2016; Streeter et al, 2012), and improvements in sleep (Khalsa et al., 2004; Mustian et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). However, racial/ethnic minorities and individuals of low SES remain underrepresented demographics in the existing yoga literature.

Several barriers to yoga participation have been identified in the literature, which also could constitute potential explanations surrounding the lack of ethnic and socio-economic diversity in yoga classes and yoga research. The perceived high costs associated with yoga, including clothing and equipment (Atkinson & Permuth-Levine, 2009), and beliefs that yoga is mainly practiced by white, thin females (Smith & Atencio, 2017) could present specific barriers to individuals of low SES as well as racial/ethnic minorities.

Nonetheless, while a few investigations suggest the acceptability and positive benefits of yoga interventions for racial/ethnic minorities (Keosaian et al., 2016; Middleton et al., 2017; Saper et al., 2009; Saper et al., 2013), the literature lacks a clear understanding of beliefs surrounding yoga and perceived barriers to yoga participation among these populations. Further, of the limited yoga research that includes racial/ethnic minorities and/or individuals with a low SES background, study samples lack representation of individuals with no yoga experience and most commonly involve exit interviews, conducted after the respondent already participated in a yoga intervention. Thus, the attitudes and perceptions of yoga among vulnerable populations who have no yoga experience or were lost to follow up during yoga intervention studies remain largely undocumented.

We address this gap through a qualitative investigation of perceptions, barriers, and facilitators of yoga among racially/ethnically diverse adults both with and without yoga experience, recruited from a low-income housing community. As a whole, the literature lacks in-depth qualitative examinations of beliefs surrounding yoga participation; investigations among vulnerable populations are even more scant (Middleton et al., 2017). Thus, our investigation may help researchers and other stakeholders design yoga programs and recruitment practices that are more appropriate and attractive to demographics underrepresented in both yoga classes and yoga research.

The aims of the present study are to: (1) investigate beliefs and attitudes of yoga and perceived barriers and facilitators of yoga participation and home yoga practice among racially/ethnically diverse individuals recruited from a low-income housing community; and (2) inform researchers on future recruitment, study design, and intervention practices for a future acceptability and feasibility study investigating the effects of yoga on sleep.

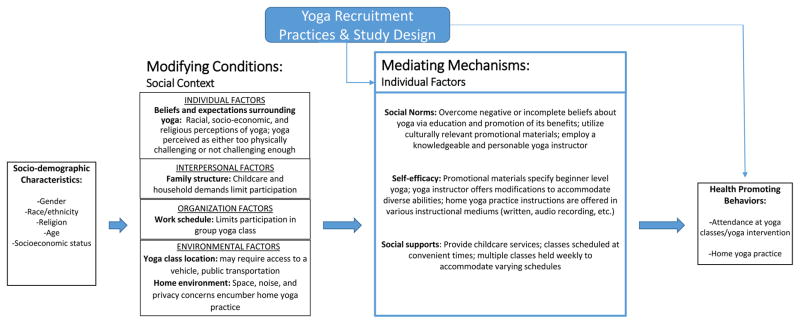

Our investigation, including the design of the focus group/interview guide, was informed by the Social Contextual Model (SCM) of Health Behavior Change (Sorensen et al., 2007). The SCM is a multi-level approach to understanding how psychosocial factors (e.g., education, income) influence health behaviors. Influences on health behaviors include factors that can be classified as either modifying conditions or mediating mechanisms. Modifying conditions are factors that can affect outcomes, or response to the intervention, but are not amenable to the direct intervention (i.e. participants’ work schedules). Understanding modifying conditions provides important context for researchers and can assist in developing mediating mechanisms (Nagler et al., 2013; Sorensen et al., 2004). Mediating mechanisms are factors that are amenable to change and can be targeted by an intervention (i.e. conducting yoga classes at convenient times to accommodate work schedules). Thus, the SCM model is useful when designing an intervention and developing recruitment practices; researchers can use this framework to identify barriers to participation and identify what factors are amenable to change and should be considered in intervention development and design. In the discussion, we utilize the SCM model to classify our findings as moderating conditions or mediating mechanisms to yoga participation, thereby highlighting relevant contextual factors that are important for yoga stakeholders to consider in study design, recruitment practices, and implementation of successful yoga interventions.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants and Materials

Given the interest in ultimately designing an intervention to promote healthy sleep in adults, eligible participants were over age 18, English speaking, and reported sleeping fewer than six hours a night on average. Participants were recruited with the assistance of housing community staff, who were encouraged to recruit individuals both with and without yoga experience to ensure varying levels of yoga familiarity. All interviews were conducted at the low-income housing community to enhance participation. A theory-informed semi-structured interview guide (Table 1), was developed using the SCM model, to investigate multi-level barriers and facilitators to yoga practice.

Table 1.

Semi-structured interview and focus group guide

|

Written informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. To best accommodate varying schedules, participants were invited to attend either a focus group or an individual interview. An experienced moderator (EK) conducted both the individual, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Interviews and focus groups lasted between one and two hours and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants were compensated with a $25 grocery store gift card. Partners Health Care Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all study procedures and materials.

2.2 Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted iteratively using Nvivo software, and included a review of the emergent themes. First, to inform study investigators of research design and recruitment considerations for a subsequent yoga intervention, one author (NK) openly coded all transcripts using a conventional thematic analysis approach and developed a table listing the major emerging themes.

Second, to ensure the trustworthiness of the data, a more systematic analytics approach was employed. In this iteration of analysis, another researcher (RR) independently reviewed and coded the transcripts using a thematic analysis approach that minimized attributions according to preconceived themes (Boyatzis, 1998). RR and NK then develop a codebook by discussing and documenting the codes, coding categories, sub-categories, and definitions. Next, several authors (SR, NK, RR, DJ, MQ) who represent an interdisciplinary team of researchers, reviewed, discussed, and finalized the codebook. Then, RR recoded all interviews per the codebook and developed an updated analytic table with the emerging themes and the representative quotes. Another author (CS) conducted an audit of the emerging themes by reviewing the analytic table, followed by a review of the interview transcriptions (Armstrong, Gosling, Weinman, & Marteau, 1997; Barbour, 2001). Following these procedures, the major themes were finalized. Discrepancies between themes, data interpretation, and associated codes were discussed and resolved among the authors.

3. Results

3.1 Participant Demographics

A total of 24 respondents participated in either a focus group or an individual interview. Nineteen participants took part in one of three focus groups (3–10 participants each) and five participants took part in a semi-structured interview (n=5). As detailed in Table 3, nearly 60% of the sample was comprised of racial/ethnic minorities. Each focus group was comprised of at least one participant with no yoga experience, and 80% (4/5) of the individual interviews were with participants who never practiced yoga. Participants were between the ages of 20–81, with a mean age of 47.9 (SD=15.7). The sample was predominantly female (75%); nearly 70% did not have a college degree (Table 2), and half of participants reported being employed full-time (Table 2).

Table 3.

Racial and ethnic distribution of the study population

| Ethnic category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Females | Males | Total | Percentage | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 | 1 | 3 | 12.5% |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 16 | 5 | 21 | 87.5% |

|

| ||||

| Racial Categories | ||||

|

| ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% |

| Asian | 4 | 0 | 4 | 16.7% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% |

| Black or African American | 5 | 1 | 6 | 25% |

| White | 6 | 4 | 10 | 41.7% |

| Other | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4.2% |

Table 2.

Overall participant characteristics

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean | 47.9 (SD=15.7) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 18 | 75.0 |

| Male | 6 | 25.0 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 7 | 29.2 |

| Some college | 9 | 37.5 |

| College graduate and higher | 7 | 29.2 |

| No report | 1 | 4.1 |

| Employment | ||

| Employed full time | 12 | 50.0 |

| Employed part time | 7 | 29.2 |

| Retired | 2 | 8.3 |

| Disabled | 2 | 8.3 |

| No report | 1 | 4.2 |

3.2 Major Themes

Several major themes emerged surrounding overall perceptions of yoga and yoga practitioners, and barriers and facilitators to practicing yoga in classes and at home. In terms of barriers and facilitators to yoga practice, participants shared key preferences on optimal yoga class scheduling, yoga instructor characteristics, yoga messaging and advertisements, and the feasibility of home yoga practice. Study participants’ beliefs about yoga, and barriers and facilitators to practice offer insights for yoga researchers and other yoga stakeholders to consider when designing yoga interventions for marginalized populations.

3.2.1 Overall perceptions of yoga and yoga practitioners

3.2.1.a Mind-Body Benefits

Understandings and beliefs about yoga can undoubtedly influence one’s decision to participate in a yoga intervention or attend a yoga class. A paramount theme was that most participants viewed yoga as a mind-body practice with multi-faceted effects. Perceived benefits of yoga included physical health, mental health, and overall well-being. For example, yoga was described as, “So you’re massaging your brain, your mind, your breathing, everything all at once,” (Interview #2). In addition:

So yoga, it’s a method or a concentration of a focus, breathing, flexibility, strength training, and most importantly, peaceful. And it requires a lot of stretching and a lot of poses and a lot of exercising, and most importantly, lots of meditation (Focus Group #3).

Predominantly, participants highlighted the perceived mental health benefits of yoga, such as “[you do yoga to] relax your head,” (Focus Group #2). Another participant described yoga as a “calming way to exercise,” (Interview #1).

Improvements in range of motion and flexibility were the most commonly perceived physical benefits of yoga among respondents both with and without prior yoga experience: “I don’t remember why I tried. But why I liked it, it was like the best stretch ever. It feels really good afterwards,” (Focus Group #1). Similarly, respondents who never practiced yoga also perceived yoga as a tool for improving flexibility.

3.2.1.b Sleep Benefits

Participants were specifically asked about their perceptions of yoga as a tool for improving sleep (Table 1). Some thought that yoga could improve their sleep by promoting relaxation. Another respondent thought the sleep benefits of yoga were simply a consequence of the tiring effects of physical activity: “When I would go to the gym …I would get home tired, and it would help me go to bed. I was exhausted from exercising so it helped,” (Focus Group #3). Two participants stated they were “not sure” (Focus Group #3; Interview #3) yoga could improve sleep. Other participants said they would have to try yoga before they could comment on the potential sleep benefits.

3.2.1.c Perceptions of Yoga Practitioners

Participants believed yoga to be an activity for individuals with superior physical abilities. For example, “people who can balance really well,” (Interview #5) and individuals who are “…very flexible and [they] do a lot of stuff that I’m like, ‘Wow, you can do that?’” (Focus Group #3). Conversely, two participants considered yoga to be an exercise practiced by people of varying physical abilities and demographics. For example: “I’ve seen all types of people do it. So, you know, there’s people at my gym that do it, so there’s men, women, some younger crowds” (Interview #4).

3.2.2 Barriers to Yoga Engagement

3.2.2.a Lack of physical/weight loss benefits

Several themes emerged that constitute barriers to yoga engagement. A perceived lack of physicality emerged as a barrier to yoga participation. Yoga was described as “…a body exercise where they just use their body to do stretching…” (Interview #5). Another participant stated: “[Yoga is].. more like stretching from what I’m told.” (Interview #3). Another non-yoga practitioner seemed surprised when she learned about the physical aspects of yoga:

I always thought it was meditation of some sort, but I’ve never heard that yoga is a little intense and it’s a really good workout. Like, I never thought of it like when I go to Zumba class or cardio, I’m going to sweat. I never [thought of it] that way. (Focus Group #3).

Going further, two participants were uncertain about the effectiveness of yoga for weight loss. One participant described her current successful weight loss regimen and credited eating healthfully and walking, and then asked the moderator: “will yoga help you lose weight?” (Focus Group #2) Another participant remarked how she lost 40 pounds “between yoga, the exercise, the juicing” and commented: “…even though I don’t think that’s what yoga is necessarily for” (Interview #1). Thus, individuals with weight loss or physical activity goals might be less motivated to participate in yoga.

Preference for other physical activities was another barrier to yoga participation. One respondent stated “I like another exercise. I like dancing” (Focus Group #1). Another respondent who never practiced yoga stated that she was not interested in trying yoga because “I like walking” (Focus Group #1).

3.2.2.b Safety and Accessibility Concerns

There were some safety concerns among both healthy individuals and individuals with physical limitations that, “You could sometimes hurt yourself, sometimes,” (Focus Group #2). One participant with a physical limitation explained: “…I do have a bad rotator cuff issue… so I’m really concerned about that,” (Focus Group #3). Another participant with fibromyalgia expressed a fear that exercise and yoga would exacerbate her pain. Two others were deterred by the leg cramps they felt when in yoga positions.

3.2.2.c Scheduling and Time Constraints

Scheduling difficulties and time constraints were also identified as barriers. When asked about challenges surrounding practicing yoga, one participant responded: “that damned job …. you’ve got to eat” (Focus Group #2). “Busyness,” (Focus Group #2), “family obligations,” (Focus Group #2), and time needed for cooking and cleaning were invoked as barriers.

Scheduled yoga classes especially could present barriers to participation. As one participant stated:

And you’ve got a mother who, maybe even if she did want to go to a yoga class, it’s six to eight, you know? She’s trying to put food on the table, or make sure the homework is done, and make sure the lunches are done for tomorrow, you know? (Focus Group #2)

These barriers might not be as salient for other forms of exercise that can occur more spontaneously. The same respondent explained that she is a walker and, “[with walking] you can make your own schedule…it’ [not like] a class…” (Focus Group #2)

In contrast, a few participants remarked that they do not face any barriers to yoga participation, specifically due to the infrastructure within the housing community. This specific low-income housing community provided an on-site gym, yoga classes, as well as childcare for free or at a subsidized rate.

3.2.3 Facilitators of Yoga Engagement

3.2.3.a Positive Yoga Instructor Characteristics

Themes were identified that could facilitate yoga engagement. Positive yoga instructor characteristics was a dominant theme. Respondents felt that the yoga instructor was integral to providing a positive yoga experience. Desirable yoga instructor characteristics include effective communication skills, personable, down-to earth, engaged, and knowledgeable--“you know, not just into like the spandex, but really knowledgeable,” (Focus Group #2). Table 4 depicts this theme and representative quotes in greater detail. Respondents also alluded to the importance of having a relatable yoga instructor: “Someone that comes in that’s…from a place where we’re from and not with that Beacon Hill attitude,” (Focus Group #1).

Table 4.

“The Teacher is what’s going to make the class:” Desired yoga instructor characteristics

| Characteristics | Representative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal factors | Relatable and enthusiastic | “Someone that comes in that’s…from a place where we’re from and not with that Beacon Hill attitude” (Focus Group #1) “Just somebody who’s upbeat, great personality, and makes it fun.” (Interview #3) |

| Attentive to students | “…I stopped going because I felt I could injure myself, and no one would notice…” (Focus Group #3) “…very informative…willing to, you know, show you how to do it the right way, instead of just not saying anything. Assuming you would know how to do it…” (Interview #4) “…you can tell when someone is really committed…not like they’ve got the knowledge, they want to impart the knowledge, but they want to impart it at your level.” (Focus Group #2) |

|

| Uses skillset to accommodate diverse students with varying ages and levels | “She would say, ‘…because you can’t raise your arm too high, just go like this.’” (Focus Group #3) “I guess that would be the main thing. One who had experience with a variety of people, in terms of younger people, older people.” (Focus Group #3) |

|

| Clear communication | “They would just need to speak very clearly… clear instructions on what I’m doing, or how I’m doing.” (Focus Group #2) | |

| Patience | “…for those who may struggle a little more, or can’t get something, just to have patience.” (Interview #5) | |

| Consistent teacher builds a relationship | “I would probably want the same instructor…it’s helpful if I’m working with somebody that I can go to, especially if I’m having a problem or difficulties” (Interview #5) | |

Respondents were specifically asked their yoga instructor’s preferred gender. The majority indicated no preference about gender; however, at least two respondents preferred a female (same gender) instructor. There was no preference indicated for dividing classes by age, and most respondents did not express discomfort with having mixed gendered classes. Conversely, two participants preferred all female (same-sex) classes. For example:

… I mean it’s already bad enough being in a class [with] women [who] already can do it better, so just to have men in there would probably make it just even more uncomfortable,” (Interview #5).

3.2.3.b Yoga Class Level and Scheduling

Yoga classes with an easy/beginner level of difficulty were portrayed to be a motivator of yoga attendance among some participants. For example:

“If they had a really easy, easy class …for those who just really can’t hold their body a certain way or who … don’t have that good body strength, like, just real [sic] easy, easy class, like real [sic] simple that, like, a kid can do. I probably could work my way up to doing more stuff that goes into yoga (Interview #5)

Overall, respondents stated they would be most attracted to attending classes one to two times a week compared to a more frequent schedule, and for class lengths to be between 30–90 minutes, with most preferring 45-minute classes. Respondents also stated that their participation would depend on the time the yoga classes were offered. Participants indicated that having multiple choices, in the morning or evening, would be optimal.

3.2.3.c Yoga Messaging and Advertising

Participants shared several ideas for successful messaging and advertising around yoga classes in their community. Relaxation, stress reduction, physical health, and improved sleep were commonly described as attractive benefits to yoga participation that could be considered when designing promotional materials. One participant commented:

I think there’s enough exercise around here with this new gym. I think if, you know, you are stressed …[the] meditation or decompressing, de-stressing, it might give people that don’t care about the exercise but care about the stress of raising kids the opportunity to think about it (Focus Group #2).

Another participant found it important to have a clear understanding of the yoga class prior to participation. Specifically, “I want to know more of what it means, what it’s about, what I’ll be getting myself into before I go into the class,” (Interview #1). Yoga messages should therefore describe class levels and activities clearly and promote the relaxation and mind-body benefits of yoga.

3.2.4 Yoga Home Practice

Participants were asked about the feasibility of a nightly, 20-minute, yoga home practice designed to promote quality sleep in order to explore barriers and facilitators to a home yoga practice. Barriers to practice included environmental and individual barriers. One participant described her current housing environment as too crowded to allot space for yoga practice: “there’s only two rooms and I’ve got two siblings with their spouses,” (Focus Group #3). Other participants indicated concerns including children disrupting their yoga practice, lack of in-person instruction, and having a full stomach from dinner that would prevent a nighttime practice.

Most participants thought practicing for 20 minutes was feasible. However, some thought twenty minutes would be “too long” and “you would have to work up to twenty minutes.” (Focus Group #1).

Participants were asked what tools would help to facilitate a home yoga practice, and were specifically probed about the utility of a yoga manual, videos, smart phone app, and/or audio. Many respondents were interested in having access to several communication mediums including a paper booklet of yoga poses and an audio and/or video guiding them through the poses.

4. Discussion

Several major themes emerged surrounding perceptions of yoga and barriers and facilitators to yoga practice. In this section, we apply our findings to the SCM model, delineating between modifying conditions and mediating mechanisms that influence yoga participation and home yoga practice (sub-sections titled “Modifying Conditions Identified” and “Mediating Mechanisms Identified”). We also compare our findings to the relevant literature and discuss modifying conditions and mediating mechanisms identified in the existing literature that could be helpful to yoga stakeholders seeking to engage racial/ethnic minorities and low SES populations to yoga; additionally, we provide plausible explanations as to why these themes did not emerge in our data (sub-sections titled “Other Modifying Conditions” and “Other Mediating Mechanisms”).

The modifying conditions identified in our data and the relevant yoga literature were conceptualized as beliefs and expectations surrounding yoga, family structure, work schedule, yoga class location, and home environment. From these modifying conditions, several mediating mechanisms were identified that target social norms, self-efficacy, and social supports. Modifying Conditions and Mediating Mechanisms outlined in the discussion are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1*.

Social Contextual Factors Associated with Yoga Participation among Low-Income, Racially/Ethnically Diverse Adults

*Figure 1 includes only the findings generated from our research and other research reviewed in the article that is specific to yoga participation among low-income and racially/ethnically diverse adults. Additional modifying conditions and mediating mechanisms might be considered within this framework.

4.1 Modifying Conditions Identified

Pre-existing beliefs and attitudes about yoga and yoga practitioners are an important modifying condition that may facilitate or hinder recruitment, particularly in a minority population. Furthermore, beliefs and attitudes are not easily amenable to change, and yoga stakeholders might be limited in ways to alter existing beliefs and attitudes of yoga.

The belief that yoga is a relaxation tool or an activity to promote mental health may serve as both a barrier and facilitator to yoga engagement. On the one hand, yoga’s perceived relaxation benefits could attract people to yoga over other forms of exercise. Conversely, some participants did not view yoga as a vigorous form of physical activity nor as a tool for weight loss. This is also documented in the existing literature (Combs and Thorn, 2014). Thus, these perceptions might serve as barriers to individuals with weight loss or physical activity goals. In fact, in a larger quantitative study, physical exercise was the primary reason why the majority non-Hispanic white sample first began their yoga practice (Park et al., 2016).

Family structure and household demands can be a challenge to participation. Participants with children expressed the challenge of participating in scheduled yoga classes. Busy and irregular work schedules were also discussed as barriers to yoga participation.

While our participants were generally enthusiastic about home yoga practice, they revealed concerns that could impact practicing yoga at home. Environmental barriers to home yoga practice were identified including lack of space, noise, and privacy, which can be amplified in low-income neighborhoods. Therefore, future research investigating yoga should attempt to overcome or at least address these specific environmental barriers to maximize adherence to home yoga practice.

4.2 Other Modifying Conditions

Several modifying conditions have been identified in the existing literature, but did not emerge as themes in our data. The literature indicates that yoga practitioners are commonly perceived as mostly non-Hispanic white, athletic females of upper socio-economic status (Atkinson & Permuth-Levine, 2009; Smith & Atencio, 2017), potentially serving as a barrier to marginalized populations. The media can engender these beliefs as non-Hispanic white female models most commonly appear in yoga-related advertisements and magazines (Vinoski et al., 2017; Webb et al., 2017). Notably, race per se is not a strong predictor of willingness to participate in research studies (Durant et al., 2011); thus, yoga researchers should consider racial/ethnic barriers specific to yoga participation to enhance study recruitment and minority representation. While race/ethnicity was not identified among our participants, if we specifically probed for racial/ethnic perceptions of yoga practitioners, this theme may have emerged. The race/ethnicity of the moderator and non-homogenous racial/ethnic makeup of the focus groups may have also influenced the discussion.

One qualitative study documented yoga to be considered “anti-Christian” (Combs and Thorn, 2014, p. 271). Perceived religiosity of yoga did not emerge as a theme in our data, even though participants were specifically probed about this topic. This may be in part due to the context of the present research study; the on-site community gym offered yoga classes, perhaps engendering a secular impression of yoga.

Financial obstacles to yoga participation have been documented in the existing literature (Atkinson & Permuth-Levine, 2009; Quilty et al., 2013; Alexander et al., 2010), but were not discussed among our participants. Again, this is most likely because our study participants are offered subsidized and free yoga classes in their community gym. Furthermore, while not identified in our data, access to public transportation is an environmental factor that can influence yoga participation. In addition, unsafe neighborhoods could create safety concerns about attending classes, particularly in the evening. Transportation and scheduling limitations are not exclusive to yoga but exist for any physical activity that occurs outside the home or workplace. These barriers may be even more significant for under-resourced populations. Yoga researchers and stakeholders with limited resources (lack of available space, budget) might face challenges when trying to mitigate transportation barriers.

4.3 Mediating Mechanisms Identified

Our data reveal several mediating mechanisms that may influence yoga participation and can be addressed by recruitment practices and study design. While changing beliefs and expectations surrounding yoga could prove difficult, yoga stakeholders could possibly modify social norms surrounding yoga. First, promotion of the benefits of yoga could be advantageous. The existing qualitative literature has documented perceived benefits of yoga among racial/ethnic minorities (Atkinson & Permuth-Levine, 2009; Keosaian et al., 2016; Middleton et al., 2017) and more homogeneous samples (Alexander et al., 2010; Quilty et al., 2013). Respondents emphasized that yoga’s potential to promote relaxation may be a selling point on promotional materials.

Second, our findings reveal that, consistent with prior research, the yoga instructor can be essential to engaging participants (Table 4) (Keosaian et al., 2016); thus, employing a knowledgeable yoga instructor could serve as an important mediating mechanism. Research teams and yoga programs aiming to engage marginalized populations should not only consider the expertise of the yoga instructor, but also personality and teaching style. Table 4 details the participants’ perspectives on the qualities and characteristics that constitute an ideal yoga instructor.

Third, addressing self-efficacy constitutes a mediating mechanism to promote yoga engagement. Participants predominantly preferred yoga classes that were geared towards beginners, and poor self-efficacy surrounding yoga can be countered with promoting and conducting yoga classes geared towards yoga novices. Of course, a participant’s preferred level of difficulty is most likely based on prior yoga experience. Thus, yoga stakeholders should consider the level of prior yoga experience within their target population when designing yoga interventions. One participant suggested that providing a clear description of what one can expect in the yoga classes prior to participation could also facilitate participation and reduce intimidation; previous studies have also reported this theme (Combs & Thorn, 2014).

Fourth, fear of injury may represent a barrier to participation and a challenge to self-efficacy. This finding is consistent with one prior qualitative study examining beliefs about yoga among racially/ethnically diverse participants with chronic low back pain (Keosaian et al., 2016). Yoga instructors can serve as a mediating mechanism to promote self-efficacy. Our data revealed that participants preferred yoga instructors who were attentive to students and able to accommodate varying abilities (Table 4). In fact, as one participant stated: “…I stopped going[to yoga] because I felt I could injure myself, and no one would notice…” (Focus Group# 3).

Mediating mechanisms to promote self-efficacy for home yoga practice were also identified. Participants suggested offering a plethora of home yoga instructions including manuals with written instructions and images, as well as audio-visual instructions; diverse mediums and explanations may help increase the self-efficacy of beginner home yoga practitioners.

Lastly, offering social supports to enable yoga participation constitutes a mediating mechanism. Yoga researchers and stakeholders can be sensitive to scheduling and location, as has been documented in our data and by other yoga researchers (Atkinson & Permuth-Levine, 2009; Quilty et al., 2013; Alexander et al., 2010). To enhance participation and retention, the intervention can offer multiple classes per week at times convenient to the target population.

4.4 Other Mediating Mechanisms

Several mediating mechanisms to yoga participation have been identified in the existing literature that did not emerge as themes in our data. We were fortunate that the residential community of our target population offered free childcare services, therefore lack of childcare was not identified as a barrier among our participants. One participant revealed that because of childcare there is “no excuse” for not participating in yoga. Nonetheless, many childcare responsibilities, such as providing dinner, assisting with homework and maintaining bedtime routines, are not addressed by providing group childcare. Indeed, the existing literature has documented childcare issues as barriers to yoga participation (Atkinson & Permuth-Levine, 2009). Yoga researchers and other stakeholders committed to increasing the uptake of yoga can consider providing their participants with free childcare and other social supports (e.g., providing homework assistance and dinner for children while the caregiver is attending yoga).

Finally, while this theme did not emerge in our data, to address the popular belief that yoga practitioners are predominantly non-Hispanic white and of higher socio-economic status (Atkinson & Permuth-Levine, 2009; Smith & Atencio, 2017), promotional and intervention materials should be culturally relevant and portray yoga as an inclusive activity regardless of race/ethnicity and socio-economic status (Kinser & Masho, 2015).

5. Strengths, Limitations, and Conclusion

A novel feature of our study was the interest in learning about how to offer yoga as an intervention for optimizing sleep in a low-income community. The study strengths include use of a conceptual model that informed the qualitative research, and identifying factors that operate as moderators or mediators. We deliberately recruited individuals both with and without yoga experience to gain a wide appreciation of facilitators and barriers. Data were rigorously analyzed by an inter-disciplinary team. However, our data are not without limitations. First, we did not obtain information surrounding prior yoga experience in demographic questionnaires. While we can ascertain, from interview and focus group transcriptions, that yoga naïve participants constituted four of the five individual interviews, and at least one yoga naïve participant was in each focus group, we are unable to identify the total number of individuals without yoga experience in our sample. Second, qualitative findings are not considered generalizable; nonetheless; our data present a deeper understanding of barriers and facilitators to recruiting and retaining individuals of lower socio-economic status and racial/ethnic minorities to yoga programs and research studies. Lastly, our sample was recruited from a community with an on-site gym that offers yoga classes, which could have influenced perceptions about yoga and yoga practitioners. However, our sample includes yoga naïve participants who never attended a yoga class despite their seemingly easy access to yoga and, therefore, may represent more general viewpoints. Notwithstanding these limitations, our data reveal helpful information for yoga researchers and stakeholders to engage marginalized populations with yoga.

In conclusion, modifying conditions highlight the potential irremediable social contextual barriers to yoga participation, such as beliefs and expectations surrounding yoga and family and work demands that limit accessibility to classes. Mediating mechanisms highlight individual factors that researchers and stakeholders can address to improve participation in yoga, and for yoga research, for enhancing recruitment and retention. Our research suggests that a high quality and personable yoga instructor is an essential component to ensuring participant engagement among community-based yoga programs and interventions. Moreover, engaging marginalized populations through culturally relevant promotional materials can prove beneficial. Designing yoga classes to accommodate beginners, effectively advertising an “easy” level of difficulty and/or the feature of having the practice difficulty adjusted to the participants’ capabilities, as well as advertising the potential benefits of yoga can enhance participant recruitment and retention. Providing social supports such as providing childcare and offering classes at convenient times and locations, as determined by the target population, also can mitigate barriers to participation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the dedicated staff at the housing community for their support with this research, and to the respondents who made this manuscript possible.

Funding Support: Funding sources: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [5R34AT008923, 2015]

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alexander GK, et al. “I could move mountains”: adults with or at risk for type 2 diabetes reflect on their experiences with yoga practice. The Diabetes educator. 2010;36(6):965–75. doi: 10.1177/0145721710381802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong D, Gosling A, Weinman J, Marteau T. The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: an empirical study. Sociology. 1997;31(3):597–606. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson NL, Permuth-Levine R. Benefits, barriers, and cues to action of yoga practice: a focus group approach. American journal of health behavior. 2009;33(1):3–14. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ. 2001;322(7294):1115–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertisch SM, et al. Alternative mind-body therapies used by adults with medical conditions. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2009;66(6):511–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop FL, Lewith GT. Who Uses CAM? A Narrative Review of Demographic Characteristics and Health Factors Associated with CAM Use. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 2010;7(1):11–28. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyatzis R. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bussing A, et al. Yoga as a therapeutic intervention. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 2012;2012:174291. doi: 10.1155/2012/174291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarke TC, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National health statistics reports. 2015;(79):1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Combs MA, Thorn BE. Barriers and facilitators to yoga use in a population of individuals with self-reported chronic low back pain: a qualitative approach. Complementary therapies in clinical practice. 2014;20(4):268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cramer H, Lauche R, Dobos G. Characteristics of randomized controlled trials of yoga: a bibliometric analysis. BMC complementary and alternative medicine. 2014;14:328. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durant RW, et al. Different types of distrust in clinical research among whites and African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011;103(2):123–30. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30261-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field T. Yoga research review. Complementary therapies in clinical practice. 2016;24:145–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeter PE, et al. Yoga as a Therapeutic Intervention: A Bibliometric Analysis of Published Research Studies from 1967 to 2013. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2015;21(10):586–92. doi: 10.1089/acm.2015.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keosaian JE, et al. “We’re all in this together”: A qualitative study of predominantly low income minority participants in a yoga trial for chronic low back pain. Complementary therapies in medicine. 2016;24:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khalsa SB. Treatment of chronic insomnia with yoga: a preliminary study with sleep-wake diaries. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback. 2004;29(4):269–78. doi: 10.1007/s10484-004-0387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khalsa SB, Butzer B. Yoga in school settings: a research review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2016;1373(1):45–55. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinser P, Masho S. “Yoga Was My Saving Grace”: The Experience of Women Who Practice Prenatal Yoga. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2015;21(5):319–26. doi: 10.1177/1078390315610554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markula P. Changing Discourses of Postural Yoga on the Yoga Journal Covers. Communication and Sport Journal. 2014;2(2) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Middleton KR, et al. A qualitative approach exploring the acceptability of yoga for minorities living with arthritis: ‘Where are the people who look like me?’. Complementary therapies in medicine. 2017;31:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mustian KM, et al. Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(26):3233–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagler EM, et al. Designing in the social context: using the social contextual model of health behavior change to develop a tobacco control intervention for teachers in India. Health education research. 2013;28(1):113–29. doi: 10.1093/her/cys060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park CL, et al. Why practice yoga? Practitioners’ motivations for adopting and maintaining yoga practice. Journal of health psychology. 2016;21(6):887–96. doi: 10.1177/1359105314541314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quilty MT, et al. Yoga in the Real World: Perceptions, Motivators, Barriers, and patterns of Use. Global advances in health and medicine. 2013;2(1):44–9. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2013.2.1.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saper RB, et al. Comparing Once- versus Twice-Weekly Yoga Classes for Chronic Low Back Pain in Predominantly Low Income Minorities: A Randomized Dosing Trial. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 2013;2013:658030. doi: 10.1155/2013/658030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saper RB, et al. Yoga for chronic low back pain in a predominantly minority population: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Alternative therapies in health and medicine. 2009;15(6):18–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith S, Atencio M. “Yoga is yoga. Yoga is everywhere. You either practice or you don’t”: a qualitative examination of yoga social dynamics. Sport in Society. 2017;20(9):1167–1184. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorensen G, et al. Reducing social disparities in tobacco use: a social-contextual model for reducing tobacco use among blue-collar workers. American journal of public health. 2004;94(2):230–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorensen G, et al. The influence of social context on changes in fruit and vegetable consumption: results of the healthy directions studies. American journal of public health. 2007;97(7):1216–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Specialists, I.P.A.T.S.R.a.C.R. The 2016 Yoga in America Study Yoga Journal. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Streeter CC, et al. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Medical hypotheses. 2012;78(5):571–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su D, Li L. Trends in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: 2002–2007. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2011;22(1):296–310. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vinoski E, et al. Got yoga?: A longitudinal analysis of thematic content and models’ appearance-related attributes in advertisements spanning four decades of Yoga Journal. Body image. 2017;21:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang D, Hagins M. Perceived Benefits of Yoga among Urban School Students: A Qualitative Analysis. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 2016;2016:8725654. doi: 10.1155/2016/8725654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webb JB, et al. Is the “Yoga Bod” the new skinny?: A comparative content analysis of mainstream yoga lifestyle magazine covers. Body image. 2017;20:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]