Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate how environmental and structural changes to a trans outdoor work environment impacted sex workers in Vancouver, Canada. The issue of changes to the work area arose during qualitative interviews with 33 trans sex workers. In response, ethnographic walks that incorporated photography were undertaken with trans sex workers. Changes to the work environment were found to increase vulnerabilities to client violence, displace trans sex workers, and affect policing practices. Within a criminalized context, construction and gentrification enhanced vulnerabilities to violence and harassment from police and residents.

Keywords: transgender, Canada, sex work, structural violence, structural vulnerability, police, qualitative, gentrification, violence

INTRODUCTION

Structural vulnerability

The concept of structural violence was introduced by Galtung (1969) and has been widely used by other scholars to refer to how social structures and political and economic arrangements result in harm to particular populations (Farmer et al., 2004; Gupta, 2012; Shannon et al., 2008a). Building on this work, we use the concept of structural vulnerability developed by Quesada, Hart, and Bourgois (2011) to capture personal characteristics and institutional structures in addition to political and economic arrangements.

Structural vulnerability, like stigma (Link and Phelan, 2001) and structural violence (Galtung, 1969), depends upon social, economic, and political power and inequality, and this concept allows us to examine how environmental and structural changes affect trans1 sex workers. Sex work environments are influenced by social (e.g. stigma) and legal (e.g. criminalization) structures, which influence working conditions (Katsulis, 2009). Using structural vulnerability as a lens allows us to examine multiple dimensions of vulnerability including heteronormativity and cisnormativity; concepts that describe the assumption that everyone is or should be heterosexual and cissexual (non-trans) (Bauer et al., 2009).

Literature review

Previous work has highlighted the structural vulnerability of trans people and sex workers. For example, there has been an increased focus on the intersecting environmental and structural contexts of sex work (Shannon et al., 2008b; Shannon et al., 2015), with evidence indicating that sex workers’ health and safety is affected by workplace settings and contexts (Krüsi et al., 2012). Sex workers who work outdoors and in more isolated spaces have been found to experience higher rates of violence (Katsulis et al., 2015; Lowman, 2000; Shannon et al., 2009a), while sex workers in more hidden and isolated indoor spaces are vulnerable to increased violence as compared to in-call spaces (Bruckert et al., 2003; Krüsi et al., 2012; O’Doherty, 2011; Shannon et al., 2015). Also, solicitation and servicing sometimes occur in different spaces, for example, sex workers who solicit outdoors may service clients in a range of indoor spaces (Prior et al., 2013) and structural vulnerability, including licensing requirements in indoor sex work venues, contributes to sex workers’ experiences of violence and displacement to increasingly isolated indoor work sites (Anderson et al., 2015).

Lowman (2000) argues that a discourse of disposability fosters an environment of violence against sex workers. In the Canadian context of colonialism and the ongoing attempts by the state to destroy Indigenous peoples and cultures, including residential schools and displacement of land (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015), colonialism marks Indigenous bodies as disposable. Additionally, intersecting layers of colonialism, transphobia, and homophobia mark Indigenous trans bodies as disposable. As Edelman (2014: 176) argues, ‘racialized and gendered systems of disregard and disposability’ are rooted in oppressive practices including colonialism and homophobia. Therefore, we suggest that this discourse of disposability is particularly pronounced for trans sex workers who are Indigenous and who work in outdoor settings undergoing gentrification.

Sex workers’ decisions around where and how to work are constrained because sex work remains criminalized in Canada. Furthermore, there is a social hierarchy of sex work environments that reflects and reinforces stigma related to gender, race, and poverty (Hwahng and Nuttbrock, 2007). For example, work environments characterized by economic disparities tend to be areas that are more dangerous in which to work (Lewis et al., 2005; Lowman, 2000). Additionally, economic and structural constraints, such as not owning a computer or having stable housing, limit the possibility for some trans sex workers to establish working conditions that may be safer. Inequalities are embedded within social hierarchies of sex work, which reflect broader inequalities such as stigma and racism (Katsulis, 2009). This has particular consequences for trans sex workers.

Trans persons face numerous barriers to economic opportunities (Hotton et al., 2013; Transgender Law Center, 2009) and as a result sex work has been noted as one of the more accessible economic opportunities (Bhattacharjya et al., 2015; Poteat et al., 2015). Additionally, trans sex workers may have less opportunity to work in indoor sex work environments because of discrimination and sex work hierarchies (Garcia and Lehman, 2011; Lewis et al., 2005). Trans sex workers have been found to experience higher rates of violence than cisgender women and men sex workers (Cohan et al., 2006) and violent experiences are shaped by racism and economic barriers (Hwahng and Nuttbrock, 2007; Nemoto et al., 2011). Thus, trans sex workers who work in outdoor settings may be vulnerable to violence due to a complex interplay of social, structural, and environmental factors. What is less understood, however, is how environmental and structural changes to work environments impact upon the structural vulnerability of trans sex workers. As such, the objective of this study was to investigate how structural and environmental changes shaped trans persons’ working conditions.

Historical context

Historically, trans sex workers have been pushed out of newly gentrified areas of Vancouver by neighbourhood organizations and police, including when they were relocated to the Downtown Eastside (DTES) neighbourhood in the 1980s and 1990s. The police closure of two nightclubs in the mid-1970s resulted in outdoor sex work becoming more visible in the Downtown and West End (gay village) areas of the city (Lowman, 1986; Ross, 2012). During the gentrification of the West End neighbourhood, a community organization called Concerned Residents of the West End (CROWE), comprising many white gay men, launched a series of successful campaigns (e.g. lobbying governments) and vigilante actions against sex workers (Brock, 2009; Ross, 2010). In 1984 sex workers were banned from the West End by a legal injunction issued by Justice McEachern and consequently sex workers were evicted from the area (Ross and Sullivan, 2012), despite many trans sex workers living in the neighbourhood (Hamilton, 2014). The following year the federal government enacted harsher punishments for sex work in the Criminal Code, (Ross, 2012, 2010). As a result, trans sex workers were forced into the East End of downtown, and over time, the vast majority of trans sex workers were displaced to the DTES because of neighbourhood harassment, policing, and physical changes (e.g. in 2003 a trans outdoor work area was destroyed and a park was built in its place). However, the community and police campaigns to remove sex workers from specific areas of the city resulted in the displacement, not the disappearance, of sex work (Lowman, 2000). Sex work was moved to places deemed less valuable such as the DTES neighbourhood (Edelman, 2014).

Our study is situated within this historical context where a number of participants recounted how they were forced out of the West End and downtown areas. This study is also situated within the context of colonialism characterized by ongoing attempts by the state to destroy Indigenous peoples and cultures (Alfred, 2009). This includes displacement from land and forcibly removing children from home and into residential schools (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). This research took place on unceded Coast Salish territories and as we will demonstrate the colonial context continues to shape trans sex workers’ lives.

METHODS

This study uses data from semi-structured interviews with 33 trans sex workers and ethnographic walks of the trans outdoor work environment. The first author conducted the interviews between June 2012 and May 2013 at research offices in Vancouver. Participants were recruited from an open prospective cohort of sex workers (An Evaluation of Sex Workers Health Access) and three open prospective cohorts of individuals who use drugs (The At Risk Youth Study, Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study, and AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Access to Survival Services). Cohort participants, who are recruited through community outreach and from research offices located in different neighbourhoods of the city, completed structured questionnaires and clinical assessments bi-annually. The cohort methods have been described in detail elsewhere (Shannon et al., 2007; Strathdee et al., 1997; Wood et al., 2006, 2008). Participants who identified as transgender, transsexual, genderqueer, or two-spirit2 in their baseline interviews were contacted by the first author or frontline staff and invited to participate in the study. Three additional participants were referred to the study by other participants. Eligibility included (a) identifying as a person whose gender identity or expression differed from their assigned sex at birth, (b) having exchanged sex for money, (c) residing in Metro Vancouver, and (d) being 14 years of age or older. Under our ethics approval we have additional consenting procedures and a consent script for emancipated minors 14–17 years, and protocols in place for reporting violence. Interviews lasted approximately an hour and no participants declined to be interviewed or left the study after being interviewed. All participants provided written consent and were paid $20 per interview.

One of the issues that arose from these interviews was how road construction would soon disrupt the trans outdoor work area. As such, we began an ethnography of the area with trans sex workers to observe changes before, during, and after the construction. From October 2013 until March 2015 the first author and two research staff conducted five ethnographic walks with three trans sex workers (Wanda, Scarlett, and Phoebe), two of whom are Indigenous, who worked in the area. The trans sex workers were invited as key experts and completed informed written consent. The walks occurred on 2 October 2013, 16 October 2013, 9 December 2013, 5 August 2014 and 3 March 2015. One participant was involved in both the participatory analysis and the ethnographic walks. The two additional trans sex workers were selected by the first author with guidance from the frontline research staff and invited to participate in the ethnographic walks. Researchers took photographs and typed up fieldnotes promptly after each ethnographic walk. The walks lasted approximately one hour and participants were paid $30 for each walk. This study holds ethical approval through Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board and pseudonyms are used to protect the identity of participants.

The ethnographic walks resembled walking interviews, walking ethnography (Yi’En, 2014), and walk-alongs (Kusenbach, 2003). Incorporating walking as a method has been found to reveal data that is more specific to the research setting compared to seated interviews that focus more on personal experiences (Evans and Jones, 2011). Our ethnographic walks, like walking interviews and walk-alongs, combined ethnographic and interviewing techniques; however we did not conduct observations of sex work activity. We added an element of photography to document changes over time and to provide a visual opportunity for readers to engage with the data. Incorporating walking as a methodological tool allowed for a richer understanding of the study setting and meaning. Using multiple methodologies allowed us to capture historical and autobiographical evidence, and detailed snapshots of the sex work setting longitudinally.

Data analysis

Interview and ethnographic data were analysed using a theory- and data-driven approach (DeCuir-Gunby et al., 2011) guided by a framework that positions health as an outcome of social, structural, and environmental contexts (Shannon et al., 2008a; Rhodes et al., 2005). The first-level coding was conducted by the first author and involved a line-by-line analysis of interview transcripts. Additional data-driven codes and sub-codes were created during second- and third-level coding by two participants who were hired as research assistants and the first author in a process they developed, called participatory analysis.

At each participatory analysis session, a hard copy of all the quotations associated with a first-level code (e.g. drug use) was printed and then split in half, with one half of the papers analysed independently by the first author and the other by one of the peer research associates. As a second step, the sections were exchanged between the first author and the research associate. As a result, the data were analysed three times. Codes were separated analytically into sub-codes and new codes were drawn from the analysis using an inductive approach (Thomas, 2006). When new codes and sub-codes were developed they were imported into ATLAS.ti (version 7), along with theoretical notes that were imported as memos, and reviewed during a subsequent analysis session. There were 24 one-on-one analysis sessions, which ranged from two to three hours, held at the research office for the interview data. A participatory approach was initiated to ensure that trans participants analysed data. Using this approach enriched and contextualized the research findings and provided an opportunity to engage with research participants in the co-construction of knowledge (Fortin et al., 2014; Shannon et al., 2007).

The three participants who participated in the ethnographic walks also analysed the ethnographic data. The first author met with each participant for one analysis session in June 2015. During the analysis we reviewed photographs and fieldnotes, made comparisons of changes over time, and clarified and discussed the effects of the environmental and structural changes to the area.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Participants ranged in age from 23 to 52 years of age, with an average age of 39 years. Of the participants, 23 (69.7%) were of Indigenous ancestry (inclusive of First Nations and Métis), 7 (21.2%) identified as white and 3 identified as Filipino, Asian and ‘other’ visible minority. The majority of participants (n = 26, 78.8%) were currently engaged in sex work and of those, 19 (73.1%) solicited in outdoor environments with the remainder soliciting clients online and/or working with regular clients in indoor environments. There were 17 out of 19 participants who worked in outdoor environments and who reported working in the area under study, and 14 of those participants were Indigenous. Given that Indigenous persons comprise approximately 4% of the population of Canada (Statistics Canada, 2013), Indigenous persons were vastly overrepresented in our study.

Environmental and structural changes to the work environment were found to (1) increase vulnerabilities to client violence by disrupting traffic patterns, (2) influence policing practices, and (3) to displace trans sex workers through gentrification processes. Participants reported that their working conditions were increasingly unsafe because of overlapping structural vulnerabilities of construction activity (e.g. decreased client traffic), criminalization of sex work (e.g. police harassment) and gentrification (e.g. resident complaints). We begin by describing the work environment followed by the presentation of our key findings.

The work environment

Trans sex workers are generally restricted to working in this area owing to cisnormativity. As one participant stated, ‘They [cisgender sex workers] have their corners and we have ours’ (Alesha, Indigenous, 34 years old). Participants tended to work alone and camaraderie was limited, which was noted as different from working in the West End and downtown: ‘It [was] safer then too, ‘cause we all stuck together’ (Isis, white, 42 years old). The strong social networks during that time, including relationships with cisgender sex workers contributed to feelings of safety. As Kara (Indigenous, 44 years old) explains:

It was a really tight group when we worked in the West End. You looked out for each other and you did work with family groups on each corner, where there was four or five of you working together and you all looked out for each other and you were like a little family… Down there [it’s] not like that.

Thus, sex workers in this area have less cohesive relationships with trans and cisgender colleagues and there are no nearby services. Because trans sex workers are generally restricted to work in this area it was a significant event in the summer of 2013 when major road construction began.

Construction activity: Less client traffic

Traffic patterns changed drastically during construction. There was an increase in traffic, particularly during rush hours, because of the detours placed through the area. At the same time, client traffic had significantly reduced and clients were hesitant to stop with the increased attention of more traffic in the area. Participants highlighted three consequences of the traffic changes: change in sex work practices, increased competition with colleagues, and servicing clients farther down the tracks.

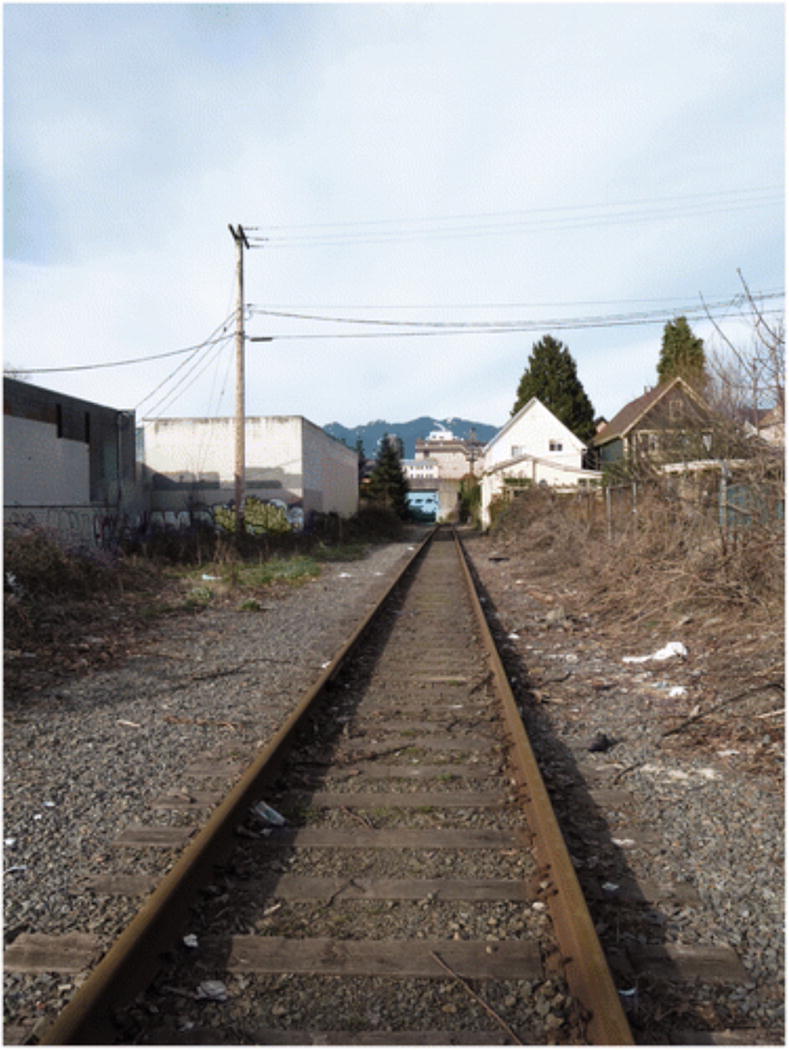

The first consequence was the pressure to change sex work practices, such as servicing clients they would otherwise refuse. Phoebe attempted to move to other areas but she was ‘chased out’ by men (e.g. boyfriends) associated with cisgender sex workers. Second, having fewer clients meant that relationships between sex workers became increasingly competitive and fractured. Participants reported having to lower their prices to contend with increased competition and undercutting. Undercutting is when sex workers charge less for their services than others in the same area. This practice was talked about negatively and was regarded as a serious problem that affected how much participants could charge clients. A third consequence was having to service clients farther down the railway tracks away from the road to avoid harassment from the police. At a certain point down the tracks one is trapped by fences and buildings on either side, and it is a long distance from the roadway (see Figure 1). In response, sex workers cut holes in the fences as an escape strategy for when clients became violent (Figure 2) Sex workers also built structures out of cardboard and tarps as places to service clients along the tracks (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Photo Tara Lyons.

Figure 2.

Photo Tara Lyons.

Figure 3.

Photo Chrissy Taylor.

Thus, the construction activity contributed to the displacement of trans sex workers and it exacerbated unsafe working conditions by disrupting traffic patterns. Trans sex workers’ structural vulnerability was enhanced through fewer economic opportunities, less choice in clients, and restricted options around where and how to work; all of which contributed to unsafe working conditions with increased vulnerability to client violence.

Policing practices: Security guards, loitering tickets, and resident complaints

A key change to policing practices during the construction was the arrival of security guards. Security guards harassed sex workers by taking their pictures and they left their vehicle headlights on, which deterred potential clients. Participants also detailed how police officers disrupted their work by issuing, or threatening to issue, loitering tickets. Steph (Indigenous, 38 years old) explained:

They usually tell me to get off the street or something like that and, you know move on … They say you’re loitering. You keep on moving or something like that, as long as you keep on moving they said it’s fine. Just keep walking around the block then.

As described earlier, there are railway tracks running through this area and these tracks are owned by CN (Canada’s national railway). During an ethnographic walk while taking a picture of a CN no trespassing sign (Figure 4) a police officer approached, as described in an excerpt from research fieldnotes:

I went to take a picture of the sign that said no trespassing and when I turned around a cop car pulled up and said there’s a $150 fine for where I was standing. I apologized and as he started to drive away, Scarlett asked, ‘Hey are you the guy who gave me a ticket last time?’ He said yes and drove off.

Figure 4.

Photo Tara Lyons.

Thus, police issued or threatened to issue different kinds of tickets – trespassing or loitering – depending on which specific area participants were working.

Participants reported that interactions with the police depended on the time of day and context. For example, in the evening, police officers were reported to be flirtatious, while during the day they were described as serving business owners. Kay (Indigenous, 47 years old) also discussed how police protected residents and businesses when she recounted an incident from the previous day:

I was on my corner working and this asshole cop come up says, you’ve worn out your welcome here… He says residents have been complaining that there’s too much noise and I said well I just got here, which I did, I hadn’t even been there five minutes…He says either you move or I’m gonna be on you all night.

The role of policing practices in the displacement of trans sex workers was a prominent theme; a theme which we present in greater detail later.

‘Well, why did you move here?’ Gentrification and displacement

Gentrification – a global urban strategy tied to the development and accumulation of wealth that transforms neighbourhoods to suit new residents (Kern, 2015; Smith, 2002) – is under way in the study setting. New businesses have opened in the neighbourhood and there is residential development, including condominiums, in an otherwise industrial area. Certain residents and businesses routinely called the police and/or verbally harassed sex workers, as described in this fieldnotes excerpt:

Scarlett discussed how she has complaints from the café on that block because they don’t like that traffic comes down to the area for sex work and not for their business. She felt frustrated by this response since she has been working there for over 15 years and is a business owner herself in her line of work. Sex workers are a part of the neighbourhood as workers and many also live in the area; however they are framed as outside, or not belonging, to the neighbourhood.

When discussing how certain residents were hostile Scarlett commented, ‘Well, why did you move here?’ She highlighted how gentrification involved the arrival of new residents and businesses who disapprove of sex work(ers) despite the presence of an established sex work environment.

Physically altering buildings was another way that businesses attempted to disrupt sex work activity. Over the course of the study it was reported, and we observed, that increasing numbers of businesses were installing gates to the front of their buildings (Figure 5). In an ethnographic walk, we came across a covered entrance to a business with a new gate installed. Phoebe (Indigenous, 39 years old) said sex workers used that space to get out of the rain and to do their makeup, whereas now the gate was locked at night.

Figure 5.

Photo Tara Lyons.

Participants actively fostered relationships with neighbours and businesses as a way to negotiate structural vulnerability. Scarlett explained that a key part of her work was establishing good relations with businesses as a way to prevent calls to the police. She also described efforts to establish positive relationships with new businesses because she felt there was a risk that new businesses would not interact with her amicably. Thus, gentrification and shifts in the neighbourhood made more work for Scarlett. Similarly, Phoebe said sex workers try to be quiet and respectful of the residents.

The displacement of trans sex workers was a central theme running through the findings. Construction activity, policing practices, and gentrification all worked to displace sex workers and clients. As a result participants attempted to relocate and/or to service clients farther down the railway tracks. It was reported, and we observed, that there were fewer trans sex workers in the area during and after the construction. It was unclear however, where trans sex workers had been displaced to.

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate how overlapping structural vulnerabilities of construction activity, criminalization of sex work, and gentrification made working conditions more unsafe and contributed to the displacement of trans sex workers. A key finding concerns how the changes we observed increased trans sex workers’ vulnerability to client violence. Sex workers in our study and in other settings (Sanders, 2004a) have reported that screening potential clients, including negotiating the terms of the transaction, assessing whether clients are under the influence of drugs, is a key aspect of managing potential client violence. Sanders (2004a) conceptualizes this as a continuum of risk where sex workers have to balance avoiding violence with earning money. Trans sex workers in other settings have also reported feeling that violence was unavoidable (Rhodes et al., 2008; Sausa et al., 2007), and the study by Sausa and colleagues (2007) revealed the understanding of inevitable client violence was juxtaposed to financial needs. (Krüsi et al., 2014; Sanders, 2004a). Research has also demonstrated that sex workers with zoning restrictions resulting from previous criminal charges (‘red zones’) and those displaced working areas away from main streets due to policing were more likely to experience client violence (Shannon et al., 2009a, 2009b).

A second key finding concerns the role of policing practices and gentrification in contributing to unsafe working conditions and displacement. The collision of gentrification and sex work has a long history in Vancouver, as we have documented, as well as in other cities (Hubbard and Sanders, 2003; Sanders, 2004b). Like participants in our study, trans sex workers in Ross’ studies recounted that working conditions in the West End in the 1970s and early 1980s were safer because sex workers were included in the community and were working closely with each other; however this changed dramatically with the 1984 legal injunction (Hamilton, 2014; Ross, 2012). Gentrification promotes middle-class lifestyles as well as middle-class values that regard sex work as inappropriate, which leads to policy changes and/or community campaigns to remove sex work(ers) from the neighbourhood (Lyons et al., 2015). Additionally, as has been documented in Amsterdam’s red-light district, areas to where ‘disposable’ bodies were once displaced often shifts when land value shifts due to globalization (Edelman, 2014; Poteat et al., 2016). Gentrification and colonial practices regulate where racialized and gendered bodies ‘belong’ (Edelman, 2014).

Across many settings, efforts to ‘design out crime’ and urban planning can often recreate power and class differentials, whereby marginalized individuals are excluded from public spaces (Hubbard, 2004; Krüsi et al., 2016). Social cohesion among sex workers has been found to support the negotiation of condom use with clients (Argento et al., 2015; Ghose et al., 2008; Lippman et al., 2010) and thus environmental and structural changes that fracture sex workers’ relationships exacerbate structural vulnerabilities. Policing practices continue to be instrumental in processes of gentrification as demonstrated in our study. For example, making complaints against sex workers is a common tactic used by residents and businesses to remove sex workers from an area (Ross and Sullivan, 2012).

Furthermore, construction activity and gentrification practices, such as installing gates, physically altered the area and enhanced structural vulnerabilities. Mapping of a social isolation index in sex work environments has shown that working in areas of reduced lighting, industrial or residential areas (as compared to commercial areas) were associated with increased harms to sex workers (Deering et al., 2014). Increased construction and police presence around the 2010 Vancouver Olympics were also found to displace sex workers and disrupt access to clients (Deering et al., 2012). In Atkins and Laing’s (2012) study of a men’s sex work environment, the installation of lights and surveillance cameras resulted in sex workers walking longer distances along a canal. As in our study, sex workers were pushed into a more isolated area where they improvised ways to increase their safety. Participants also engaged in relationship building with residents and businesses to negotiate the enhanced structural vulnerabilities related to construction and gentrification.

These results are situated within contexts of transmisogyny, hetero- and cisnormativity, colonialism, and the criminalization of sex work; all of which serve to exacerbate structural vulnerability. Indigenous trans sex workers were overrepresented in our sample in part due to effects of colonization, such as the displacement of Indigenous people (Alfred, 2009; Hunt, 2013). This also reflects the racialized character of the work environment. Trans sex workers’ experiences of sex work, violence, and policing take different forms depending on one’s gender identity, ethnicity, and/or Indigenous ancestry (de Vries, 2015; Hwahng and Nuttbrock, 2007; Meyer, 2012). For example, African American trans women sex workers in the study by Nemoto and colleagues (2011) reported significantly higher incidents of police harassment compared to white, Asian, and Latina trans women sex workers. Given our sample was comprised primarily of trans women, it is important to contextualize our findings within a context of transmisogyny whereby trans women, particularly Indigenous and trans women of color and those who are marginalized, experience high rates of violence and exclusion (Pyne, 2015). The findings illustrate how transmisogyny functions, along with interlocking discriminations related to gender, sex work, class, and racism, to enhance structural vulnerabilities of trans sex workers. Additionally, work venues reflect broader contexts of racism, classism, and heteronormativity (Katsulis et al., 2015). Ross (2012) argued that the gentrification of the West End was inherently racist, gendered, and classed. Our study demonstrates how the trans outdoor sex work environment continues to reflect and reinforce broader stigmas related to gender, colonialism, and poverty.

It has been argued that sex workers resist criminalization by moving to different areas of the city (Hubbard and Sanders, 2003); however for trans sex workers, relocation brought increased vulnerability to violence from potential clients who may not know they are trans and from cisgender sex workers and associates. Participants expanded the working area (e.g. farther down the tracks) and altered the physical environment by cutting holes in fences and creating structures to service clients. Thus, sex workers in our study strategically shaped the work environment (Laing and Cook, 2014); however trans sex workers have multiple overlapping layers of structural vulnerability which constrains options. For example, within a criminalized context, trans sex workers are restricted to working in specific areas and under the threat of arrest as demonstrated by our findings. Within a context of cis- and heteronormativity, trans sex workers face social exclusion and barriers to economic opportunities as is well documented in the literature (Moolchaem et al., 2015; White Hughto et al., 2015). Within a colonial context Indigenous trans sex workers are more likely to face police harassment and arrest as evidenced by the vast overrepresentation of Indigenous persons in Canadian jails and prisons. Indigenous persons comprise approximately 4.3% of the Canadian population (Statistics Canada, 2013), yet make up 22.8% of those incarcerated (The Correctional Investigator, 2014).

Policy implications

We caution against environmental and structural changes that disrupt trans sex work settings given that these interventions enhance structural vulnerabilities and foster displacement. The City of Vancouver has been a municipal leader in sex work policy by developing a Task Force on Sex Work and Sexual Exploitation, and Sex Work Response Guidelines for city employees who interact with sex workers (City of Vancouver, September 2015). However, trans sex workers have been left out of policy and planning discussions related to gentrification and construction in their work environment. In the future, sex workers must be meaningfully included in community consultations and decisions on urban planning. Additionally, it is imperative that structural interventions that address cis- and heteronormativity and the effects of colonization are embedded within social structures (e.g. police) to improve the health, safety, and economic security of trans sex workers.

Owing to legal challenges brought by sex workers, Canada’s sex work laws have undergone recent changes. In December 2013, three sections of Canada’s prostitution laws, including communicating in public for the purchase of prostitution, were ruled unconstitutional for violating sex workers’ rights (Sampson, 2014). In response, a year later the Canadian government implemented new sex work legislation that criminalizes the purchase of sex for the first time in Canadian history, and continues to criminalize communication in public for the purpose of sex work (Government of Canada, 6 November 2014). This legislation has been criticized for its potential to contribute to even greater harm to sex workers (Krüsi et al., 2014). Thus, Canadian sex work laws continue to violate sex workers’ rights and contribute to trans sex workers’ vulnerability to violence and unsafe working conditions. Indigenous trans sex workers may be more vulnerable to the harms of criminalization as evidenced by the vast overrepresentation of Indigenous persons, particularly Indigenous women, in Canadian jails and prisons (The Correctional Investigator, 2014). Therefore, it is imperative that sex work laws are changed in order to increase the safety of the work environment for trans sex workers. As one participant stated ‘sex work needs to be legalized so we can have brothels; clean and safe places to work.’

Limitations and future directions

Little is known about the experiences of two-spirit sex workers; however, including two-spirit participants in this study may have served to overshadow their unique experiences. Thus, future research would benefit from two-spirit specific research conducted by Indigenous peoples and/or in accordance with Indigenous research methods and ethics. This research may not be comparable to other sex work settings. The study is limited to trans sex workers accounts and the incorporation of police, resident and business accounts in future research may contribute to a fuller picture of the impacts of environmental and structural changes. Similarly, because residential development is ongoing we may not have captured the full effect of gentrification. As such, we have undertaken a second stage of the ethnography to observe the impacts of new condominium developments. Lastly, the data used in this analysis are based on self-report and may be susceptible to response biases, which may include an underreporting of violence. We were unable to locate other studies of this sex work setting and therefore despite certain limitations this study presents novel evidence rooted in multiple methods.

Environmental and structural changes in a context of cis- and heteronormativity, criminalization, and colonialism increased the structural vulnerability of trans sex workers, particularly Indigenous trans sex workers. As such, our study underscores the need for greater attention to structural vulnerability when planning construction, residential development in areas where individuals disproportionately impacted by social and structural inequities live and work.

Acknowledgments

We thank all those who contributed their time and expertise to this project, particularly the participants, research assistants, community advisory board members and partner agencies. We are grateful for the ethnographic work conducted by Chrissy Taylor and Solanna Anderson.

Funding

This research was supported by operating grants from the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA033147). At the time of the research TL and AK were supported through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. WS was supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. KS was partially supported by a Canada Research Chair in Global Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Scholar Award.

Footnotes

Trans is an umbrella term referring to diverse group of individuals who cross socially constructed gender and sex boundaries with a gender identity or expression not typically associated with their assigned sex.

Two-spirit is a dynamic concept that sits outside of binary understandings of sex and gender and is used to describe an Indigenous person who has feminine and masculine spirits (Fieland et al., 2007). Two-spirit is also used by some indigenous people to describe their sexual orientation as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or queer (see Ristock et al., 2010).

References

- Alfred T. Colonialism and state dependency. Journal de la sante’ autochtone. 2009;5:42–60. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Jia JX, Liu V, et al. Violence prevention and municipal licensing of indoor sex work venues in the Greater Vancouver Area: Narratives of migrant sex workers, managers and business owners. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015;17(7):825–841. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1008046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argento E, Duff P, Bingham B, et al. Social cohesion among sex workers and client condom refusal in a Canadian setting: Implications for structural and community-led interventions. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;20:1275. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1230-8. Available at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10461-015-1230-8 (accessed 3 November 2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins M, Laing M. Walking the beat and doing business: Exploring spaces of male sex work and public sex. Sexualities. 2012;15(5–6):622–643. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, Hammond R, Travers R, et al. ‘I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives’: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20(5):348–361. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjya M, Fulu E, Murthy L, et al. The right(s) evidence – Sex work, violence and HIV in Asia: A multi-country qualitative study. Bangkok: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and Asia Pacific Network of Sex Workers (CASAM); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brock D. Making Work, Making Trouble: The Social Regulation of Sexual Labour. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckert C, Parent C, Robitaille P. Erotic Service/Erotic Dance Establishments: Two Types of Marginalized Labor. Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- City of Vancouver. City of Vancouver sex work response guidelines: A balanced approach to safety, health and well-being for sex workers and neighbourhoods impacted by sex work. Vancouver, BC: Sep, 2015. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cohan D, Lutnick A, Davidson P, et al. Sex worker health: San Francisco style. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2006;82(5):418–422. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering KN, Chettiar J, Chan K, et al. Sex work and the public health impacts of the 2010 Olympic Games. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2012 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050235. DOI: sextrans-2011-050235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deering KN, Rusch M, Amram O, et al. Piloting a ‘spatial isolation’ index: The built environment and sexual and drug use risks to sex workers. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCuir-Gunby JT, Marshall PL, McCulloch AW. Developing and using a codebook for the analysis of interview data: An example from a professional development research project. Field Methods. 2011;23(2):136–155. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries KM. Transgender people of color at the center: Conceptualizing a new intersectional model. Ethnicities. 2015;15(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman EA. ‘Walking while transgender’: Necropolitical regulations of trans feminine bodies of colour in the nation’s capital. In: Haritaworn J, Kuntsman A, Posocco S, editors. Queer Necropolitics. New York: Routledge; 2014. pp. 172–190. [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Jones P. The walking interview: Methodology, mobility and place. Applied Geography. 2011;31(2):849–858. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P, Bourgois P, ScheperHughes N, et al. An anthropology of structural violence 1. Current Anthropology. 2004;45(3):305–325. [Google Scholar]

- Fieland K, Walters K, Simoni J. Determinants of health among Two-Spirit American Indians and Alaska Natives. In: Meyer I, Northridge M, editors. The Health of Sexual Minorities. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 268–300. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin R, Jackson SF, Maher J, et al. I WAS HERE: Young mothers who have experienced homelessness use Photovoice and participatory qualitative analysis to demonstrate strengths and assets. Global Health Promotion. 2014;22(1):8–20. doi: 10.1177/1757975914528960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtung J. Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research. 1969;6(3):167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MV, Lehman Y. Issues concerning the informality and outdoor sex work performed by travestis in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(6):1211–1221. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghose T, Swendeman D, George S, et al. Mobilizing collective identity to reduce HIV risk among sex workers in Sonagachi, India: The boundaries, consciousness, negotiation framework. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(2):311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Statutes of Canada 2014: Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act. Second Session, Forty-first Parliament, 62–63 Elizabeth II, 2013–2014. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; Nov 6, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A. Red Tape: Bureaucracy, Structural Violence, and Poverty in India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL. The golden age of prostitution: One woman’s personal account of an outdoor brothel in Vancouver, 1975–1984. In: Irving D, Raj R, editors. Trans Activism in Canada: A Reader. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2014. pp. 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hotton AL, Garofalo R, Kuhns LM, et al. Substance use as a mediator of the relationship between life stress and sexual risk among young transgender women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2013;25(1):62–71. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard P. Cleansing the metropolis: Sex work and the politics of zero tolerance. Urban Studies. 2004;41(9):1687–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard P, Sanders T. Making space for sex work: Female street prostitution and the production of urban space. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2003;27(1):75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S. Decolonizing sex work: Developing an intersectional indigenous approach. In: van der Meulen E, Durisin EM, Love V, editors. Selling Sex: Experience, Advocacy, and Research on Sex Work in Canada. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press; 2013. pp. 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hwahng SJ, Nuttbrock L. Sex workers, fem queens, and cross-dressers: Differential marginalizations and HIV vulnerabilities among three ethnocultural maleto-female transgender communities in New York City. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2007;4(4):36–59. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2007.4.4.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsulis Y. Sex Work and the City: The Social Geography of Health and Safety in Tijuana, Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Katsulis Y, Durfee A, Lopez V, et al. Predictors of workplace violence among female sex workers in Tijuana, Mexico. Violence Against Women. 2015;21(5):571–597. doi: 10.1177/1077801214545283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern L. Rhythms of gentrification: Eventfulness and slow violence in a happening neighbourhood. Cultural Geographies. 2015;23(3):441–457. [Google Scholar]

- Krüsi A, Chettiar J, Ridgway A, et al. Negotiating safety and sexual risk reduction with clients in unsanctioned safer indoor sex work environments: A qualitative study. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(6):1154–1159. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüsi A, Kerr T, Taylor C, et al. ‘They won’t change it back in their heads that we’re trash’: The intersection of sex work related stigma and evolving policing strategies. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2016;38(7):1137–1150. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12436. Epub 26 April 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüsi A, Pacey K, Bird L, et al. Criminalisation of clients: Reproducing vulnerabilities for violence and poor health among street-based sex workers in Canada – qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(6):e005191. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005191. Published online 2 June 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusenbach M. Street phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography. 2003;4(3):455–485. [Google Scholar]

- Laing M, Cook IR. Governing sex work in the city. Geography Compass. 2014;8(8):505–515. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Maticka-Tyndale E, Shaver F, et al. Managing risk and safety on the job: The experiences of Canadian sex workers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 2005;17(1–2):147–167. [Google Scholar]; 20 Sexualities 0(0); Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Lippman SA, Donini A, Díaz J, et al. Social-environmental factors and protective sexual behavior among sex workers: The Encontros intervention in Brazil. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S216–223. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowman J. Prostitution in Vancouver: Some notes on the genesis of a social problem. Canadian Journal of Criminology. 1986;28:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lowman J. Violence and the outlaw status of (street) prostitution in Canada. Violence Against Women. 2000;6(9):987–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons T, Krüsi A, Pierre L, et al. Negotiating violence in the context of transphobia and criminalization: The experiences of trans sex workers in Vancouver, Canada. Qualitative Health Research. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1049732315613311. DOI: 1049732315613311. Available at: http://qhr.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/10/28/1049732315613311.full (accessed 31 October 2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Meyer D. An intersectional analysis of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people’s evaluations of anti-queer violence. Gender & Society. 2012;26(6):849–873. [Google Scholar]

- Moolchaem P, Liamputtong P, O’Halloran P, et al. The lived experiences of transgender persons: A meta-synthesis. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2015;27(2):143–171. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T, Bodeker B, Iwamoto M. Social support, exposure to violence and transphobia, and correlates of depression among male-to-female transgender women with a history of sex work. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(10):1980–1988. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty T. Victimization in off-street sex industry work. Violence Against Women. 2011;17(7):944–963. doi: 10.1177/1077801211412917. Epub 10 June 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T, German D, Flynn C. The conflation of gender and sex: Gaps and opportunities in HIV data among transgender women and MSM. Global Public Health. 2016;11(7–8):1–14. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1134615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Radix A, et al. HIV risk and preventive interventions in transgender women sex workers. The Lancet. 2015;385(9964):274–286. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60833-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior J, Hubbard P, Birch P. Sex worker victimization, modes of working, and location in New South Wales, Australia: A geography of victimization. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50(6):574–586. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.668975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne J. Transfeminist theory and action: Trans women and the contested terrain of women’s services. In: O’Neill B, Swan T, Mule N, editors. LGBTQ people and Social Work: Intersectional Perspectives. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars Press; 2015. pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada J, Hart LK, Bourgois P. Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Medical Anthropology. 2011;30(4):339–362. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Simic M, Baros S, et al. Police violence and sexual risk among female and transvestite sex workers in Serbia: Qualitative study. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2008;337(7669):560–563. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, et al. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(5):1026–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristock J, Zoccole A, Passante L. Aboriginal Two-Spirit and LGBTQ Migration, Mobility and Health Research Project: Final Report. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ross BL. Sex and (evacuation from) the city: The moral and legal regulation of sex workers in Vancouver’s West End, 1975–1985. Sexualities. 2010;13(2):197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Ross BL. Outdoor brothel culture: The un/making of a transsexual stroll in Vancouver’s West End, 1975–1984. Journal of Historical Sociology. 2012;25(1):126–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6443.2011.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross B, Sullivan R. Tracing lines of horizontal hostility: How sex workers and gay activists battled for space, voice, and belonging in Vancouver, 1975–1985. Sexualities. 2012;15(5–6):604–621. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson L. The obscenities of this country: Canada v. Bedford and the reform of Canadian prostitution laws. Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy. 2014;22:137–172. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders T. A continuum of risk? The management of health, physical and emotional risks by female sex workers. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2004a;26(5):557–574. doi: 10.1111/j.0141-9889.2004.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders T. The risks of street prostitution: Punters, police and protesters. Urban Studies. 2004b;41(9):1703–1717. [Google Scholar]

- Sausa L, Keatley J, Operario D. Perceived risks and benefits of sex work among transgender women of color in San Francisco. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36(6):768–777. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Bright V, Allinott S, et al. Community-based HIV prevention research among substance-using women in survival sex work: The Maka Project Partnership. Harm Reduction Journal. 2007;4(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-20. Available at: https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1477-7517-4-20 (accessed 24 April 2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, et al. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social Science & Medicine. 2008a;66(4):911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, et al. Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2009a;339(7718):442–445. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Rusch M, Shoveller J, et al. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental-structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008b;19(2):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: Influence of structural determinants. The Lancet. 2015;385(9962):55–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, et al. Structural and environmental barriers to condom use negotiation with clients among female sex workers: Implications for HIV-prevention strategies and policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2009b;99(4):659. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N. New Globalism, New urbanism: Gentrification as global urban strategy. Antipode. 2002;34(3):427–450. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Aboriginal peoples in Canada: First Nations people, Me’tis and Inuit: National household survey, 2011. Ottawa, ON: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, et al. Needle exchange is not enough: Lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11(8):F59–65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Correctional Investigator. Annual Report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator 2013–2014. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation. 2006;27(2):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Transgender Law Center. State of Transgender California. San Francisco, CA: Transgender Law Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg, MB: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;147:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Hogg RS, Lima V, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and survival in HIV-infected injection drug users. JAMA. 2008;300(5):550–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Stoltz J-A, Montaner J, et al. Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: The ARYS study. Harm Reduction Journal. 2006;3(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-18. Available at: http://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1477-7517-3-18 (accessed 11 March 2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi’En C. Telling stories of the city: Walking ethnography, affective materialities, and mobile encounters. Space and Culture. 2014;17(3):211–223. Published online before print 30 October 2013. [Google Scholar]