Abstract

Background and Aims

A comprehensive understanding of the rhizosphere priming effect (RPE) on the decomposition of soil organic carbon (SOC) requires an integration of many factors. It is unclear how N form-induced change in soil pH affects the RPE and SOC sequestration.

Methods

This study compared the change in the RPE under supply of NO3-N and NH4-N. The effect of the RPE on the mineralization of soil N and hence its availability to plant and microbes was also examined using a 15N-labelled N source.

Key Results

The supply of NH4-N decreased rhizosphere pH by 0.16–0.38 units, and resulted in a decreased or negative RPE. In contrast, NO3-N nutrition increased rhizosphere pH by 0.19–0.78 units, and led to a persistently positive RPE. The amounts of rhizosphere-primed C were positively correlated with rhizosphere pH. Rhizosphere pH affected the RPE mainly through influencing microbial biomass, activity and utilization of root exudates, and the availability of SOC to microbes. Furthermore, the amount of rhizosphere primed C correlated negatively with microbial biomass atom% 15N (R2 0.77–0.98, n = 12), suggesting that microbes in the rhizosphere acted as the immediate sink for N released from enhanced SOC decomposition via the RPE.

Conclusion

N form was an important factor affecting the magnitude and direction of the RPE via its effect on rhizosphere pH. Rhizosphere pH needs to be considered in SOC and RPE modelling.

Keywords: 13C natural abundance, microbial N immobilization, N form, 15N, rhizosphere acidification

INTRODUCTION

Rhizosphere effects can induce an increase or decrease in the decomposition of soil organic carbon (SOC), which is frequently referred to as a positive or negative rhizosphere priming effect (RPE). These rhizosphere effects include root release of organic C and N substances, depletion of nutrients and water, or root-induced chemical changes such as soil pH (Kuzyakov, 2002; Hinsinger et al., 2003). In particular, root exudates can stimulate microbial growth and activity, generally leading to an increase in SOC turnover in the rhizosphere (Cheng and Kuzyakov, 2005; Dijkstra and Cheng, 2007; Phillips et al., 2011). Plant traits such as plant phenology and shoot and root biomass (Fu and Cheng, 2002; Cheng et al., 2003), and environmental factors such as light intensity (Kuzyakov and Cheng, 2001), temperature (Zhu and Cheng, 2011) and CO2 concentration (Carney et al., 2007) could have a great impact on the RPE through affecting the quantity or quality of root exudates.

Root-mediated changes in rhizosphere pH are a well-documented interaction between soil and the root interface (Hinsinger et al., 2003; Tang et al., 2004), but its impact on the RPE has seldom been studied. The release of protons is believed to be largely influenced by plant N nutrition. In general, ammonium (NH4-N) addition leads to rhizosphere acidification because of excess uptake of cations over anions, while nitrate (NO3-N) nutrition causes rhizosphere alkalization (Hinsinger et al., 2003). Ramirez et al. (2010) found that soil microbial respiration was closely correlated with changes in soil pH following application of different N sources. Under field conditions, long-term SOC sequestration could be favoured by the acidity generated during NH4-N oxidation (Malhi et al., 1997; Zhang and Wang, 2012). Soil pH can affect the decomposition of SOC directly through affecting SOC solubility or indirectly via changes in microbial activity (Andersson et al., 2000; Briedis et al., 2012). This then suggests that the N-form-induced change in rhizosphere pH may also have an impact on the root-induced decomposition of SOC, namely the RPE. Addition of N either increases (Cheng and Johnson, 1998), decreases (Liljeroth et al., 1994) or has no effect on the RPE (Cheng et al., 2003). Contradictory mechanisms have been proposed to explain the observed effects of N on the RPE (Kuzyakov et al., 2000; Fontaine et al., 2003). It is not clear whether the influence of N addition on the RPE also depends on the source of N applied due to its role in regulating rhizosphere pH.

While factors affecting the RPE have been extensively examined, few studies have looked at how the RPE may affect the mineralization of soil N and hence its availability for plant uptake. Owing to the close link between SOC decomposition and N mineralization, increased N availability has been expected in the rhizosphere following enhanced RPE (Murphy et al., 2015; Rousk et al., 2016). Under N-limited conditions, positive RPEs have been proposed as an adaptive behaviour of plants to gain N through microbial mineralization of N-rich SOC (Kuzyakov, 2002; Luo et al., 2006; Dijkstra et al., 2013). However, enhanced N immobilization has also been detected in the rhizosphere characterized by continuous supply of labile C via rhizodeposits (Zak et al., 2000; Dijkstra et al., 2013). Therefore, positive RPEs have resulted in both increased and decreased net N mineralization (Dijkstra et al., 2009; Phillips et al., 2011; Bengtson et al., 2012). Even in the case of increased N mineralization, rhizosphere-primed C did not correlate with rhizosphere-primed N (Cheng, 2009; Dijkstra et al., 2009). The effect of the RPE on the contribution of soil-derived N to plant uptake remains largely unknown.

This study aimed to examine the change in the RPE under supply of NO3-N and NH4-N. The application of different N sources was expected to produce a major difference in rhizosphere pH. The study also used a 15N-labelled N source to examine the fate of soil-derived N following an enhanced RPE. We hypothesized that the plants supplied with NH4-N would have lower RPEs than those fed with NO3-N due to NH4-induced rhizosphere acidification, in comparison to the alkalization caused by NO3-N supply.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil

Topsoil (0–10 cm) was collected from a C4 Kangaroo grassland (Themeda triandra) in Gulgong, New South Wales (32°11′S, 149°33′E). The soil was air-dried and sieved through a 2-mm sieve. The soil was a granite-derived sandy loam. It had the following basic properties: pH 5.0 (0.01 m CaCl2), organic C 27 g kg−1, total N 1.6 g kg−1, clay 130 g kg−1 and soil pH buffer capacity 30 mmolc kg−1 unit pH−1. The δ13C value of the SOC was −18.0 ‰.

Experiment set up

The experiment consisted of three plant treatments, two N forms and three replicates. The three plant treatments were wheat, white lupin and the no-plant control. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L. ‘Yitpi’) and white lupin (Lupinus albus L. ‘Kiev’) were grown in PVC columns (diameter 10 cm, height 40 cm) containing 2.8 kg air-dried C4 soil. To prevent anaerobic conditions, a 3-cm layer of plastic beads sealed in nylon bags (mesh size 50 µm) was placed at the bottom portion of each column. Prior to planting, basal nutrients were mixed into the soil at following rates (mg kg−1): KH2PO4, 180; K2SO4, 120; CaCl2.2H2O, 180; MgSO4.7H2O, 50; MnSO4.H2O, 15; ZnSO4.7H2O, 9; CuSO4.5H2O, 6; Na2MoO4.2H2O, 0.4; Na[FeEDTA].3H2O, 5.5. The two N forms were NH4-N and NO3-N, applied as Ca(15NO3)2 (2 atom% 15N) and (15NH4)2SO4 (2 atom% 15N), respectively, at a rate of 30 mg N kg−1 at sowing. To minimize possible nitrification and maximize NH4-N uptake by plants as the NH4-N form, all N sources were applied twice weekly at 15 mg N kg−1 from week 4. The total amount of N supplied was 90 and 240 mg N kg−1 for the harvests at day 42 and 80, respectively. They were applied 1 d before the total CO2-trapping, and 3 d before the destructive harvest. Soil columns without plants but with the two N forms (30 mg N kg−1 once at the start of the experiment) were included as no-plant controls. To test whether possible nitrification affected soil pH and consequently total amount of soil-derived CO2 released from the control columns with N applied once, compared with planted columns with regular N additions, another set of control columns were set up to include five rates of NH4-N (10, 30, 50, 70 and 100 mg N kg−1). The columns were destructively harvested at the vegetative (day 42) and flowering stage (day 80) (three replicates at each time). An additional eight pots (two species × two N forms × two replicates) were filled with washed fine sand plus 10 g of C3 soil as an inoculant, to account for isotopic fractionation between the root tissue and root-respired CO2.

Planting and CO2 trapping

The experiment was conducted in a controlled environmental room with 20 °C and 18 °C during the day and night, respectively, a light intensity of 400 µmol m−2 s−1 and a day length of 14 h. Twelve germinated seeds of wheat and eight seeds of white lupin were sown in a row in the centre of each column. After emergence, plants were thinned to six per column for wheat, and four for white lupin. All the columns were weighed and maintained at 80 % water-holding capacity by watering with reverse osmosis water for the soil columns and with Hoagland solution (Hoagland and Arnon, 1950) for the sand columns. The sand columns had been watered with Hoagland solution twice daily to meet the requirement for water and nutrient by plants. A modified CO2-trapping system (Wang et al., 2016) was used to trap total below-ground CO2 produced in each column 3 d before each harvest. Briefly, CO2-free air was introduced through an air inlet at the top of each column after being pumped through 1 m NaOH via an air stone. The outlet, on the opposite side of the soil column, was fitted with a vacuum line passing through two CO2 traps containing 150 mL of 0.5 m NaOH. The simultaneous operation of the pump and vacuum facilitated airflow through the soil columns, reduced the pressure within the headspace and stopped possible leaking around the plant stems. The CO2 was trapped for 48 h in 150 mL of 0.5 m NaOH at each harvest.

Harvest and measurements

At harvest, plant shoots were cut off at the soil surface one column at a time. The rhizosphere soil was collected by gently shaking off soil adhering to the roots. All rhizosphere soil was sieved through a 2-mm sieve, and sub-samples were immediately put into a plastic bag and stored at 4 °C for determination of soil microbial biomass C (MBC), microbial biomass N (MBN) and soil respiration. Another set of samples were air-dried for determination of soil pH, total organic C and N. Plant roots were carefully washed with water, and root length was quantified using WinRHIZO Pro 2003b (Regent Instruments, Quebec City, Canada) and an EPSON EU-35 scanner (Seiko Epson Corp., Suwa, Japan). All plant materials were oven-dried at 70 °C, weighed and ground in a ball mill.

The δ13C in the shoot and root samples was analysed using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Sercon 20–22, Crewe, UK). The C and N concentrations of shoot, root and rhizosphere soil were determined by dry combustion using a CHNS analyser (PerkinElmer EA2400, Shelton, CT, USA). Soil pH was measured in 0.01 m CaCl2 (1: 5 soil solution ratio) after end-over-end shaking for 1 h and centrifuging at 700 g for 10 min.

Microbial respiration in the rhizosphere soil was determined after 12 h of incubation at 25 °C to give an indication of the quantity of labile C substrates (e.g. root exudates) and microbial activity (Wang et al., 2016). The CO2 concentration within the headspace of jars was measured using an infrared gas analyser (Servomex 4210 Industrial Gas Analyser, Cowborough, UK) (Rukshana et al., 2012). MBC and MBN were determined following the chloroform fumigation-extraction procedure according to Vance et al. (1987a). Briefly, 8 g of fumigated or non-fumigated moist soil was extracted using 40 mL of 0.5 m K2SO4. Total SOC in the extracts was determined colorimetrically following wet digestion with dichromate-sulfuric acid at 135 °C for 30 min (Cai et al., 2011). Total soluble N was determined by persulphate oxidation of both fumigated and non-fumigated extracts (Cabrera and Beare, 1993), and the final concentrations of inorganic N (NH4+ + NO3−) were measured using a QuickChem 8500 flow injection analyser (Lachat Instruments, Loveland, CO, USA). MBC and MBN were calculated as the difference in concentrations of total organic C and total N in extracts between fumigated and non-fumigated soils, adjusted by a proportionality coefficient of 0.45 (Jenkinson et al., 2004). Soil inorganic N was measured on the non-fumigated and non-oxidized 0.5 m K2SO4 extracts using the flow injection analyser. Before determination of microbial biomass 13C and 15N by mass spectrometry, both fumigated and un-fumigated K2SO4 extracts were freeze-dried, and the dried salts were finely ground using a mortar and pestle (Dijkstra et al., 2006b).

The amount of CO2 trapped in 0.5 m NaOH was determined by titrating 10 mL of NaOH solution with 0.5 m HCl after addition of 5 mL 1 m BaCl2. To produce SrCO3 precipitates for δ13C analysis, 5 mL of 1 m SrCl2 was added to another 10 mL of NaOH solution. The suspension pH was then adjusted to 7.0 using 0.3 m HCl. The δ13C of the SrCO3 was analysed by mass spectrometry.

Calculations and statistical analysis

To partition the total CO2 efflux using the 13C natural abundance method, the following equations were applied (Mary et al., 1992):

where Ct is the total C from below-ground CO2, C4 is the amount of CO2-C derived from C4 soil, δt is the δ13C value of the Ct, δ3 is the δ13C value of the root-derived C (CO2 trapped from the sand columns) and δ4 is the δ13C value of the C4 soil C (CO2 trapped from the no-plant control columns). Ccontrol is the amount of CO2-C evolved from the column without plants. Cprimed is the total primed C.

The isotopic signature of microbial biomass was calculated as follows (Dijkstra et al., 2006b):

atom%15NMB = (atom% 15NF*NF – atom% 15NUF*NUF)/NMB

where MB, F and UF are microbial biomass, fumigated and un-fumigated fractions, respectively. CF, NF, CUF and NUF are total dissolved organic C and N in the fumigated and un-fumigated extracts, respectively.

A two-way ANOVA was conducted using Genstat (11th Version) (VSN International, Hemel Hempstead, UK) to assess the effect of N form and plant species at each harvest. Where necessary, square-root transformation of the data was performed to obtain a normal distribution. Significant (P ≤ 0.05) differences between means were identified using the Tukey’s honest significant difference test. Single linear regression analyses were used to determine the relationship between rhizosphere-primed C and soil pH or atom% 15N in microbial biomass.

RESULTS

Nitrogen form did not affect the shoot dry weight of either species. However, compared with NO3-N, NH4-N nutrition decreased root dry weight and total root length of wheat by 16 and 28 %, respectively, at day 80 (Table 1). The concentration of N in the shoot or root did not differ between the two N forms for either species. The δ13C value of CO2 trapped from the sand column (root-derived C) receiving NO3-N was 1.2–2.7 ‰ more enriched than that of the root tissues, indicating an isotopic fractionation between the root tissue and root-respired CO2 (Table 1). Given that the δ13C value of root tissue was not affected by N forms, the δ13C value of CO2 trapped from the sand columns with NO3-N addition was used to represent the root-derived C for both N treatments. Shoot biomass of both species in the sand columns was lower when N was applied as NH4-N compared with NO3-N (data not shown), probably due to low rhizosphere pH in this poorly buffered system.

Table 1.

Dry biomass and N concentration of shoot and roots, root length and 13C abundance in roots of wheat and white lupin supplied with NO3-N and NH4-N at days 42 and 80

| Harvest time | Species | N form | Biomass (g per column) | N concentration (%) | Root length (m per column) | 13C abundance (‰) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoot | Root | Shoot | Root | Root | Root-derived CO2 | ||||

| Day 42 | Wheat | NO3/NH4-N | 4.04 b | 0.87 b | 5.22 b | 2.90 a | 183 b | −31.89 a | −30.6 a |

| White lupin | NO3/NH4-N | 3.45 a | 0.55 a | 4.70 a | 2.98 a | 22 a | −30.30 b | −28.7 b | |

| Day 80 | Wheat | NO3-N | 15.47 b | 2.50 c | 3.41 a | 2.01 a | 437 c | −32.24 a | −30.7 a |

| NH4-N | 14.90 b | 2.11 b | 3.32 a | 1.93 a | 314 b | −32.26 a | |||

| White lupin | NO3-N | 11.23 a | 1.05 a | 4.19 b | 3.00 b | 30 a | −31.74 b | −29.0 b | |

| NH4-N | 10.19 a | 1.13 a | 4.23 b | 3.17 b | 32 a | −31.62 b | |||

| Two-way ANOVA | |||||||||

| Day 42 | Species | ** | ** | * | n.s. | *** | *** | *** | |

| N form | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |||

| Species × N form | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | |||

| Day 80 | Species | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | |

| N form | * | * | n.s. | n.s. | *** | n.s. | |||

| Species × N form | n.s. | * | n.s. | n.s. | *** | n.s. | |||

n.s., *, ** and *** represent P > 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively. For each column, different letters indicate significant differences between means for a given harvest time (two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s test, P < 0.05). At day 42, the effect of N form and interactions between N from and species are not significant and thus only the main effects of species (average of two N forms) are presented.

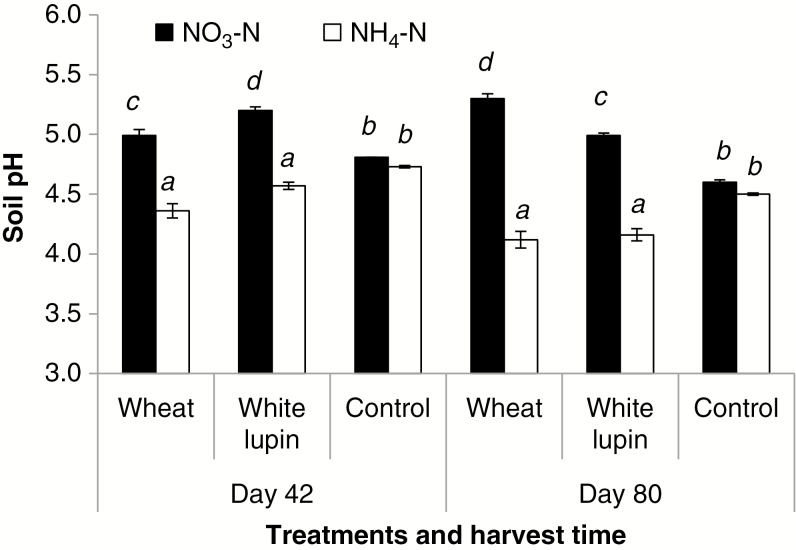

When compared with the no-plant control, rhizosphere pH was 0.37 units lower at both harvests of wheat fed with NH4-N, but was 0.19 and 0.78 units higher for wheat fed with NO3-N at days 42 and 80, respectively (Fig. 1). Supply of NH4-N decreased soil pH by 0.16–0.39 units in the rhizosphere of white lupin, relative to the no-plant control, in contrast to alkalization of 0.2–0.4 units under NO3-N supply. Neither soil pH nor total CO2 production from the control columns were affected by the rate of NH4-N (data not shown) or N form (Figs 1 and 2A). The little change in soil pH following addition of NH4-N at different rates was mainly attributed to the relatively high pH buffering capacity of the C4 soil used in this study.

Fig. 1.

Soil pH of the no-plant control and the rhizosphere of wheat and white lupin supplied with NO3-N or NH4-N at days 42 and 80. Error bars represent ±s.e.m. of three replicates. Different italic letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments at each harvest time (Tukey’s test, P < 0.05).

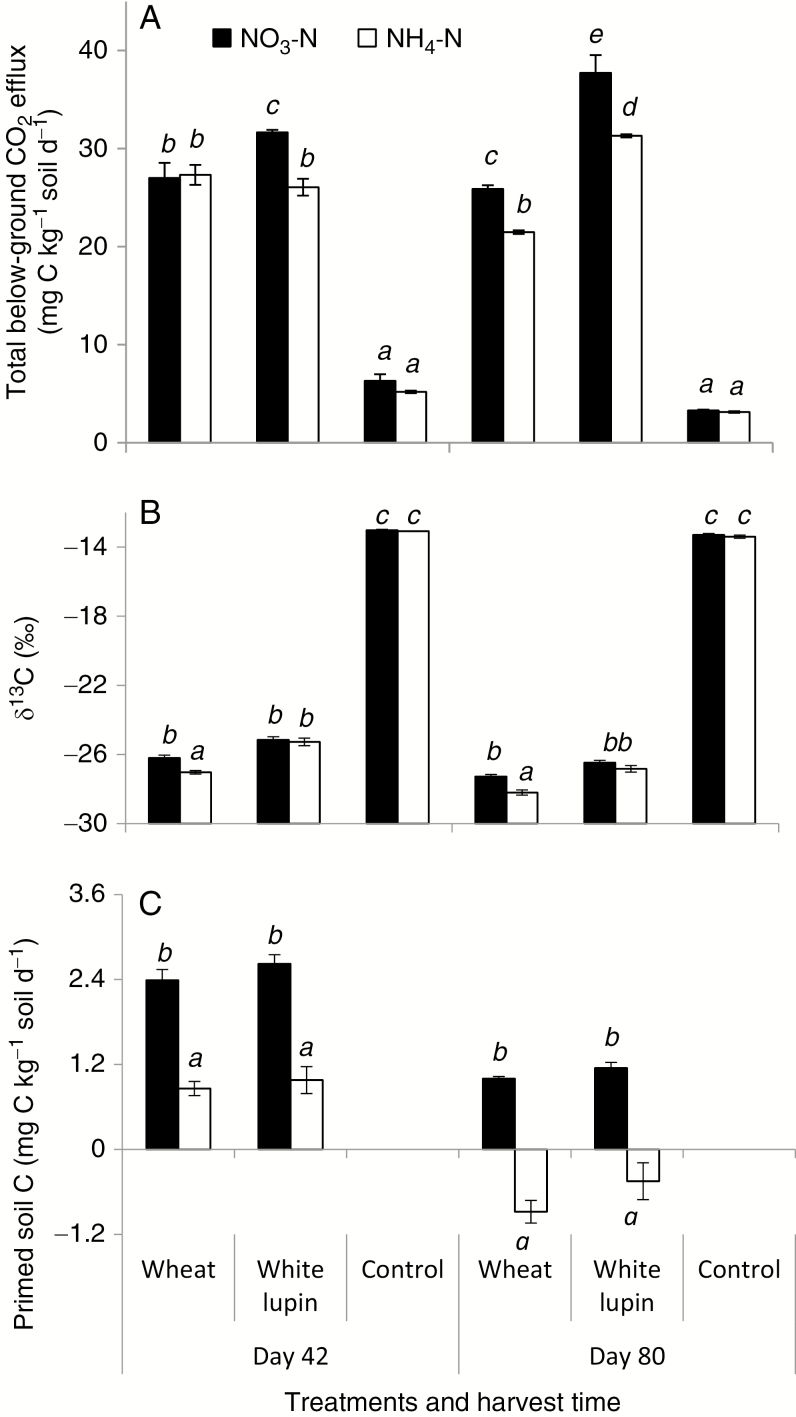

Fig. 2.

Total below-ground CO2 efflux (A), δ13C values of CO2 (B) and primed soil C (C) under wheat and white lupin fed with NO3-N and NH4-N or no-plant control at days 42 and 80. Error bars represent s.e.m. of four replicates. Different italic letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments at each harvest time (Tukey’s test, P < 0.05).

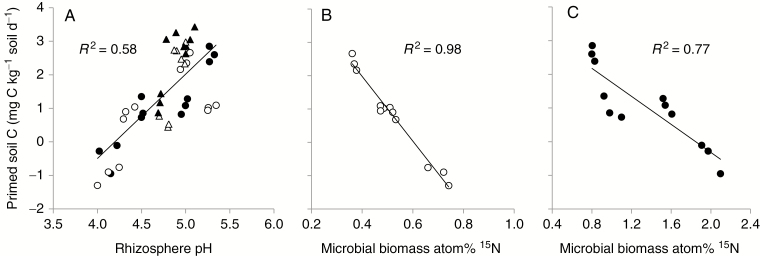

Total below-ground CO2 efflux was 17–18 % lower under NH4-N than NO3-N addition in all planted columns, except that N form did not affect the CO2 efflux under wheat at day 42 (Fig. 2A). The δ13C value of CO2 showed no difference between the two N sources for white lupin and the no-plant control, but decreased by 0.9 ‰ for wheat fed with NH4-N relative to NO3-N (Fig. 2B). The CO2 collected from the control column had a consistent δ13C value of −13.2 ‰ during the whole experiment. Regardless of plant species, N form had a significant impact on the decomposition of SOC and the RPE. A decreased or negative RPE was observed for the plants fed with NH4-N while a consistently higher and positive RPE was shown for the plants fed with NO3-N (Fig. 2C). The amounts of rhizosphere-primed C were positively correlated with rhizosphere pH (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A), and negatively correlated with the atom% 15N in the microbial biomass (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B, C). Other soil properties such as extractable organic C, soil respiration and microbial C and N were not correlated with primed C, when all data were included in the analysis. The SOC concentration in the rhizosphere of plants fed with NH4-N was 3–5 % higher (P < 0.05) than that of NO3-N (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Relationships between rhizosphere-primed soil C and rhizosphere pH (A) and microbial biomass atom% 15N for wheat (B) and white lupin (C) fed with NO3-N and NH4-N at days 42 and 80. Open and closed circles denote data for wheat and white lupin, respectively. Open and closed triangles denote the data for urea-fed wheat and N2-fixing white lupin, respectively, from Wang et al. (2016).

Table 2.

Extractable soil organic C, soil respiration, rhizosphere soil organic C (SOC), microbial C and N in the no-plant control and the rhizosphere of wheat and white lupin supplied with NO3-N or NH4-N at days 42 and 80

| Harvest time | Treatment | N form | Extractable organic C (µg C g−1 soil) | Soil respiration (µg CO2 g−1 soil) | Rhizosphere SOC (mg g–1) | Microbial C (µg C g−1 soil) | Microbial N (µg N g−1 soil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 42 | Wheat | NO3-N | 84 a | 161 b | 27.6 ab | 256 b | 20.6 b |

| NH4-N | 96 a | 186 b | 28.2 b | 216 a | 15.2 a | ||

| White lupin | NO3-N | 107 a | 387 c | 26.8 a | 376 c | 41.1 c | |

| NH4-N | 151 b | 363 c | 28.1 b | 234 ab | 24.6 b | ||

| Control | NO3-N | 90 a | 88 a | 27.4 ab | 248 ab | 24.1 b | |

| NH4-N | 86 a | 79 a | 27.3 ab | 266 b | 23.3 b | ||

| Day 80 | Wheat | NO3-N | 39 a | 247 c | 27.4 ab | 366 bc | 33.8 b |

| NH4-N | 87 b | 166 b | 28.2 c | 256 a | 23.3 a | ||

| White lupin | NO3-N | 105 b | 520 e | 26.5 a | 416 c | 46.0 c | |

| NH4-N | 146 c | 371 d | 27.9 bc | 305 ab | 29.0 b | ||

| Control | NO3-N | 77 b | 69 a | 27.0 a | 283 a | 29.3 b | |

| NH4-N | 82 b | 76 a | 27.1 a | 280 a | 27.7 b | ||

| Two-way ANOVA | |||||||

| Day 42 | Treatment | ** | ** | n.s. | * | ** | |

| N form | * | n.s. | * | * | * | ||

| Treatment × N form | ** | n.s. | * | ** | * | ||

| Day 80 | Treatment | *** | *** | * | * | *** | |

| N form | *** | *** | * | *** | *** | ||

n.s., *, ** and *** represent P > 0.05, P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments at each harvest time (Tukey’s test, P < 0.05).

The K2SO4-extractable organic C (EOC) was higher in the rhizosphere of plants fed with NH4-N than NO3-N, except for wheat at day 42 (Table 2). Noticeably, EOC in the rhizosphere of white lupin was 72 and 83 % higher under NH4-N nutrition than the no-plant control at days 42 and 80, respectively. Wheat showed little effect on EOC, except a 51 % decrease at day 80 when fed with NO3-N. The rhizosphere soil respiration during 12 h of incubation was invariably higher in the planted columns than the no-plant controls, and in the rhizosphere of white lupin than wheat. When compared between the two N forms, soil respiration was lower under NH4-N than NO3-N nutrition at day 80 for both species (Table 2).

The effect of N form on MBC and MBN in the rhizosphere soil differed between wheat and white lupin (Table 2). Microbial biomass C and MBN in the rhizosphere of white lupin supplied with NO3-N increased by 46 and 68 %, respectively, relative to the no-plant control, but remained less changed for wheat. The addition of NH4-N showed no effect on MBC, but decreased MBN in the rhizosphere of wheat, compared to the control. For both species, MBC and MBN were invariably lower under NH4-N than NO3-N supply.

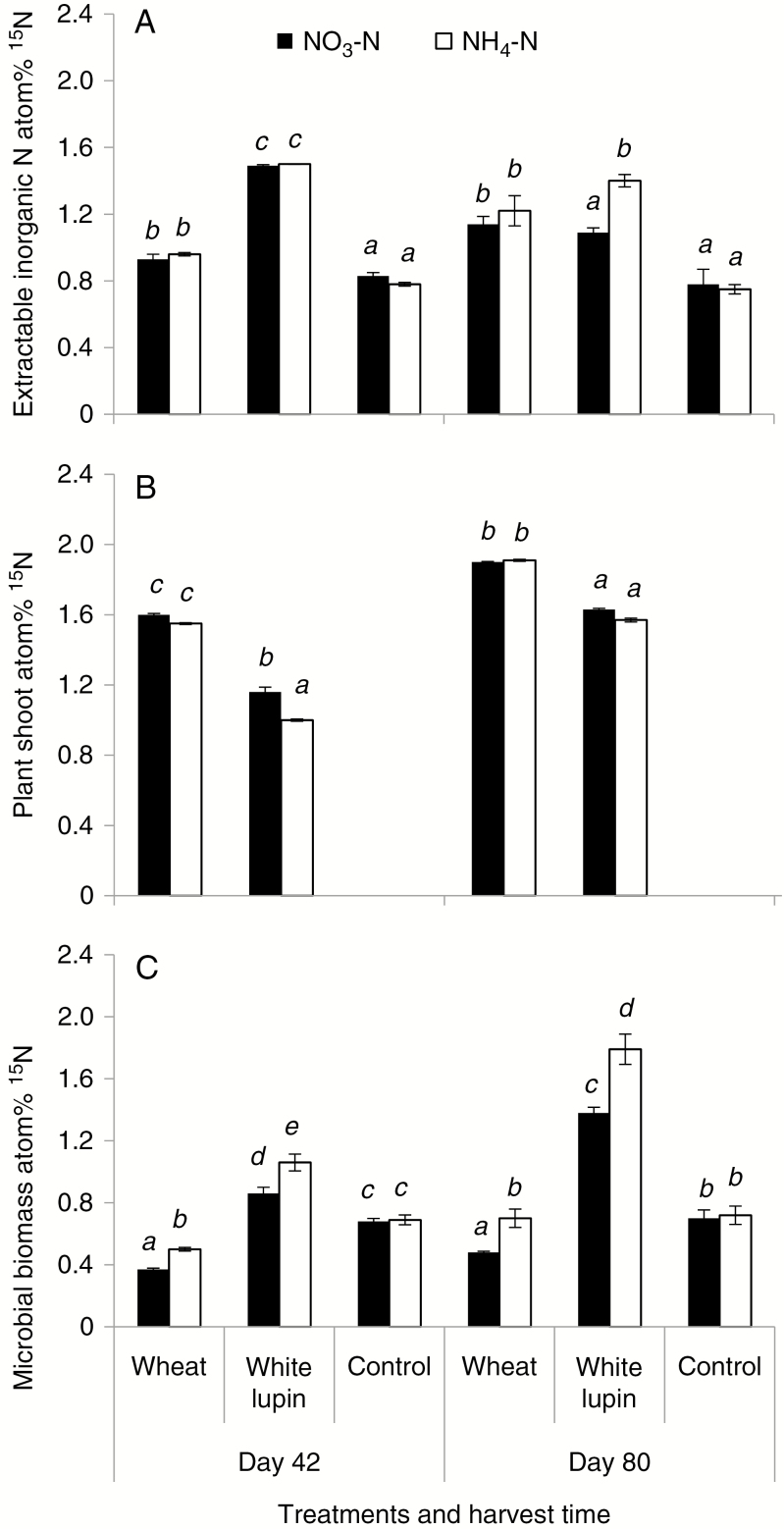

15N abundance in the extractable inorganic N in the rhizosphere did not differ between the two N sources except for white lupin at day 80 (Fig. 4A). Nitrogen form greatly affected the 15N enrichment in microbial biomass and plants (Fig. 4B, C). Microbial biomass was less enriched with 15N when NO3-N was applied, in comparison with NH4-N (Fig. 4B). Nevertheless, an opposite trend was shown in the plant shoot at day 42, although no effect of N form was detected at day 80 (Fig. 4C). In the no-plant control and bulk soil, N form did not affect microbial atom%15N.

Fig. 4.

Atom% 15N in the rhizosphere inorganic N (A), plant shoots (B) and rhizosphere microbial biomass (C) of wheat and white lupin supplied with NO3-N or NH4-N at days 42 and 80. Error bars represent s.e.m. of three replicates. Different italic letters above the bars indicate significant differences among treatments at each harvest time (Tukey’s test, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study revealed that the supply of NO3-N led to enhanced RPEs in contrast to decreased or negative RPEs caused by NH4-N addition. The higher SOC concentration in the rhizosphere of plants fed with NH4-N than NO3-N provided further evidence of reduced SOC decomposition by NH4-N nutrition. This was also consistent with the enhancement of SOC sequestration due to NH4-N fertilization reported by other studies (McAndrew and Malhi, 1992; Malhi et al., 1997; Zhang and Wang, 2012). Furthermore, the C4 soil used in this study was a mixture of different SOC pools with different δ13C values; for example, the easily decomposable C was more 13C-enriched (-13.2 ‰) than non-labile C fractions associated with soil minerals (−18.8 ‰) (Wang et al., 2016). If the persistent positive RPE resulted in the decomposition of more stable SOC at the late stage, the NO3-induced increase in RPE might have been underestimated due to the use of δ13C values of soil-derived CO2 for the non-planted control columns (−13.2 ‰). A decreased or negative RPE following NH4-N addition should be less affected by the non-uniformity of the 13C signature among different SOC fractions. As indicated by the constant δ13C values of CO2 evolved from the control columns with time, decomposition of SOC in the absence of plants was mainly from labile C pools. Low or negative RPEs mean that the quantity of soil-derived CO2 from the planted columns was similar to or less than that from the control. Overall, N form had a large impact on both the magnitude and the direction of the RPE, and future evaluation of the effect of N addition on the RPE should also consider the form of N sources.

The effects of N form on plant biomass and root exudation (indicated by EOC and rhizosphere microbial respiration) could not account for the significant changes in the RPE. Many plant species had shown slower growth when N was applied as NH4-N relative to NO3-N (Raab and Terry, 1994; Britto and Kronzucker, 2002; Guo et al., 2002). In this study, the negative effects of NH4-N on plant growth were confirmed by decreases in root biomass and length for wheat plants at day 80. There is evidence to suggest that plants with higher shoot or root biomass generally produce greater RPEs (Fu and Cheng, 2002; Dijkstra et al., 2006a), although RPE showed no correlation with shoot and root biomass in this study. For instance, restricted root growth by NH4-N nutrition was detected only for wheat at day 80, but a decreased or negative RPE occurred for both species at both harvests. This was in line with our previous finding that plant biomass played a minor role in accounting for the RPE of species with contrasting effect on soil acidification (Wang et al., 2016). On the other hand, NH4-N rather than NO3-N nutrition could increase root exudation by plant roots, due to NH4-induced changes in root architecture such as increased branching (Martins-Loucao et al., 2000), cell death in root cortex (Brown and Hornby, 1987) or increased membrane permeability by low pH (Yin and Raven, 1998). If N form-induced changes in the quantity of root exudates was mainly responsible for the differences in the RPE between the two N forms, the RPE would be higher under NH4-N than NO3-N nutrition. Finally, no differences were detected in either 12-h soil respiration or 48-h total CO2 efflux between NH4-N- and NO3-N-amended controls with no plants, suggesting N form per se had less impact on microbial decomposition of SOC.

It is evident that rhizosphere pH was positively correlated with the amount of rhizosphere-primed C. As expected, NH4-N nutrition caused rhizosphere acidification with pH decreasing by up to 0.38 units. This resulted from H+ production during excess uptake of cations over anions by plant roots and/or, to a lesser extent, nitrification (Malhi et al., 1991). In contrast, NO3-N nutrition led to rhizosphere alkalization (increasing pH by up to 0.78 units), due to excess uptake of anions over cations (Tang et al., 1999). In decomposition studies, increasing soil pH increased the magnitude of the positive priming effect (Perelo and Munch, 2005; Luo et al., 2011), and the optimum pH was between 6 and 8 (Blagodatskaya and Kuzyakov, 2008; Nang et al., 2017). Our previous study also found that rhizosphere pH was mainly responsible for the variation in the RPE among crop species differing in rhizosphere acidification (from pH 4.1 to 5.2) (Wang et al., 2016). It is expected that the addition of NH4-N could decrease the RPE more in acid soils than in neutral or alkaline soils.

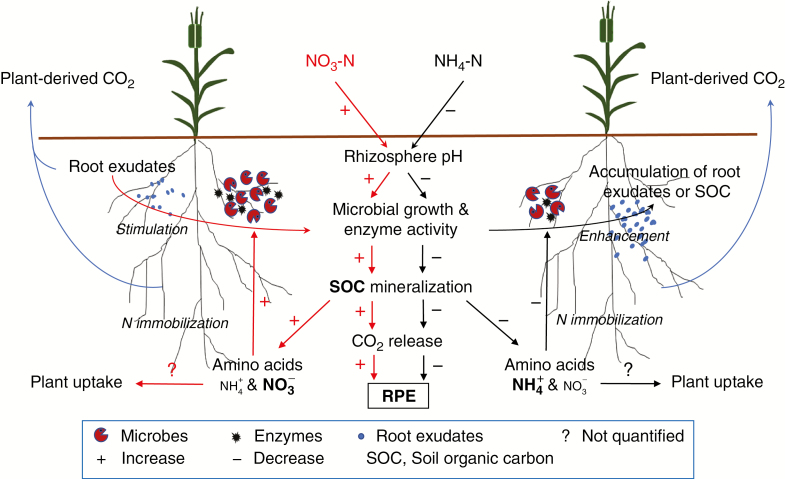

The N source-induced changes in rhizosphere pH could affect the RPE in the following ways. Firstly, low rhizosphere pH greatly decreased microbial activity and growth (Fig. 5), as indicated by lower soil respiration and microbial biomass C and N under NH4-N than NO3-N supply. In other studies, the effect of soil pH on SOC decomposition was mainly via its effect on microbial growth and activity (Andersson et al., 2000; Briedis et al., 2012), and the turnover of SOC correlated positively with soil pH in the range of 4.3–5.3 (Leifeld et al., 2008). Secondly, decreased microbial biomass and activity at low pH possibly led to inefficient use of root exudates or soluble SOC, which accounted for the greater accumulation of EOC in the rhizosphere of plants fed with NH4-N than NO3-N (Fig. 5). Negative relationships between soil pH and EOC were also observed in other studies (Vance et al., 1987b; Pietri and Brookes, 2008). Finally, addition of NO3-N might have favoured microbial utilization of SOC due to increased availability of SOC at higher pH. Increases in the solubilization or desorption of humic substances from the surface of mineral colloids were often detected following elevated soil pH by liming (Andersson et al., 2000; Garbuio et al., 2011). The activation of microbes by root exudates was believed to be the main mechanism responsible for the enhanced RPE (Kuzyakov et al., 2000), but low soil pH following NH4-N addition decreased microbial activity regardless of the quantity of root exudates.

Fig. 5.

Conceptual diagram of the effects of N form (NO3-N vs. NH4-N)-induced pH changes on the rhizosphere priming effect (the RPE) and involved N immobilization mechanisms.

Microbes in the rhizosphere acted as an immediate sink for N released from enhanced SOC decomposition via the RPE. The increase in both MBN and MBC indicated that microbial immobilization of N was enhanced by increased microbial growth. Moreover, decreased 15N abundance in microbes under NO3-N than NH4-N supply possibly reflected a greater dilution of 15N at higher RPE and an enhanced contribution of soil-derived N, relative to fertilizer-derived N. This was directly supported by the negative correlation between primed C and microbial biomass 15N abundance in the rhizosphere of the two species. The recovery of 15N in microbial biomass in the unplanted columns (Fig. 4C) and in the bulk soil of the planted columns (data not shown) did not differ between two N sources, indicating a lack of microbial discrimination between the two N forms. Norton and Firestone (1996) and Inselsbacher et al. (2010) also found that N form per se did not affect the amount of N assimilated by microbes. Immediate and rapid utilization of soil-derived N following a positive RPE by microbes was possible (Fig. 5), given the greater substrate affinities, larger specific surface area and greater spatial distribution of microbes than plant roots (Lipson and Näsholm, 2001; Kaštovská and Šantrůčková, 2011). Moreover, amino acids released during the decomposition of SOC could be more efficiently acquired by microbes before they were mineralized and came into soil solution for plant uptake (Kuzyakov and Xu, 2013). Little difference in atom% 15N in the extractable inorganic N in the rhizosphere between the two N forms, in most cases, might also reflect a rapid immobilization of soil-derived N by microbes in the case of an enhanced RPE.

An enhanced RPE under NO3-N nutrition did not result in a greater contribution of soil-derived N to plant uptake. Higher atom% 15N in white lupin fed with NO3-N than NH4-N at day 42 might indicate a faster uptake of NO3-N because of its higher mobility in the soil (Norton and Firestone, 1996; Burger and Jackson, 2003; Song et al., 2007). Also, plants fed with NH4-N might have fixed more N2 than those fed with NO3-N, due to the slower uptake or lower effectiveness of NH4-N at suppressing nitrogenase activity (Silsbury et al., 1986; Svenning et al., 1996). On the other hand, if N mineralized via the RPE under NO3-N nutrition was rapidly captured by microbes in the first place, the availability of soil-derived N to plants would decrease. Other studies also found that an enhanced RPE did not result in apparent increases in plant N uptake due to short-term N immobilization (Cheng, 2009; Dijkstra et al., 2011; Kuzyakov and Xu, 2013). Nevertheless, N immobilized by microbes with a short turnover time (days to weeks) could eventually be transferred to the forms that can be utilized by plants (Hodge et al., 2000; Cheng and Kuzyakov, 2005; Harrison et al., 2007). Overall, the contribution of the RPE to plant N uptake in this study was complicated and may have been regulated by many factors. Further studies are required to quantify the partitioning of SOC-derived N between microbes and plants in response to an enhanced RPE during short- and long-term periods.

CONCLUSION

Our results revealed that N form affected the RPE mainly through its impact on rhizosphere pH. Rhizosphere acidification under NH4-N resulted in decreased or negative RPEs and hence favoured SOC accumulation, while alkalization in the supply of NO3-N enhanced the RPE and hence SOC mineralization. Noticeably, microbes in the rhizosphere acted as the immediate sink for N released during SOC decomposition. Enhanced microbial N immobilization under NO3-N supply might delay plant uptake of soil N under field conditions. The role of N fertilization on SOC sequestration should take into account the apparent effect of N form-induced pH change on the RPE. Under field conditions, the addition of organic amendments or crop residue return is essential to replenish SOC lost via the RPE under NO3-N supply. This study also suggests that rhizosphere pH needs to be considered in SOC and RPE modelling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported under the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (project DP120104100). We thank Dr Clayton Butterly and anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript and Dr Anan Wang for technical support.

LITERATURE CITED

- Andersson S, Nilsson SI, Saetre P. 2000. Leaching of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) in mor humus as affected by temperature and pH. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 32: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson P, Barker J, Grayston SJ. 2012. Evidence of a strong coupling between root exudation, C and N availability, and stimulated SOM decomposition caused by rhizosphere priming effects. Ecology and Evolution 2: 1843–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagodatskaya E, Kuzyakov Y. 2008. Mechanisms of real and apparent priming effects and their dependence on soil microbial biomass and community structure: critical review. Biology and Fertility of Soils 45: 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Briedis C, de Moraes Sá JC, Caires EF et al. 2012. Soil organic matter pools and carbon-protection mechanisms in aggregate classes influenced by surface liming in a no-till system. Geoderma 170: 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Britto DT, Kronzucker HJ. 2002. NH4+ toxicity in higher plants: a critical review. Journal of Plant Physiology 159: 567–584. [Google Scholar]

- Brown ME, Hornby D. 1987. Effects of nitrate and ammonium on wheat roots in gnotobiotic culture: amino acids, cortical cell death and take-all (caused by Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici). Soil Biology and Biochemistry 19: 567–573. [Google Scholar]

- Burger M, Jackson LE. 2003. Microbial immobilization of ammonium and nitrate in relation to ammonification and nitrification rates in organic and conventional cropping systems. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 35: 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera M, Beare M. 1993. Alkaline persulfate oxidation for determining total nitrogen in microbial biomass extracts. Soil Science Society of America Journal 57: 1007–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Peng C, Qiu S, Li Y, Gao Y. 2011. Dichromate digestion–spectrophotometric procedure for determination of soil microbial biomass carbon in association with fumigation–extraction. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 42: 2824–2834. [Google Scholar]

- Carney KM, Hungate BA, Drake BG, Megonigal JP. 2007. Altered soil microbial community at elevated CO2 leads to loss of soil carbon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 104: 4990–4995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W. 2009. Rhizosphere priming effect: its functional relationships with microbial turnover, evapotranspiration, and C–N budgets. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 41: 1795–1801. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Johnson DW. 1998. Elevated CO2, rhizosphere processes, and soil organic matter decomposition. Plant and Soil 202: 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Kuzyakov Y. 2005. Root effects on soil organic matter decomposition. In: Zobel RW, Wright SF, eds. Roots and Soil Management: Interactions Between Roots and the Soil, Agronomy Monograph No. 48. Madison, WI, USA: American Society of Agronmy. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W, Johnson DW, Fu S. 2003. Rhizosphere effects on decomposition: controls of plant species, phenology, and fertilization. Soil Science Society of America Journal 67: 1418–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra FA, Cheng W. 2007. Interactions between soil and tree roots accelerate long-term soil carbon decomposition. Ecology Letters 10: 1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra FA, Cheng W, Johnson DW. 2006a. Plant biomass influences rhizosphere priming effects on soil organic matter decomposition in two differently managed soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 38: 2519–2526. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra P, Ishizu A, Doucett R et al. 2006b. 13C and 15N natural abundance of the soil microbial biomass. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 38: 3257–3266. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra FA, Bader NE, Johnson DW, Cheng W. 2009. Does accelerated soil organic matter decomposition in the presence of plants increase plant N availability?Soil Biology and Biochemistry 41: 1080–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra FA, Hutchinson GL, Reeder JD, LeCain DR, Morgan JA. 2011. Elevated CO2, but not defoliation, enhances N cycling and increases short-term soil N immobilization regardless of N addition in a semiarid grassland. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43: 2247–2256. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra FA, Carrillo Y, Pendall E, Morgan JA. 2013. Rhizosphere priming: a nutrient perspective. Frontiers in Microbiology 4: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine S, Mariotti A, Abbadie L. 2003. The priming effect of organic matter: a question of microbial competition?Soil Biology and Biochemistry 35: 837–843. [Google Scholar]

- Fu S, Cheng W. 2002. Rhizosphere priming effects on the decomposition of soil organic matter in C4 and C3 grassland soils. Plant and Soil 238: 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Garbuio FJ, Jones DL, Alleoni LR, Murphy DV, Caires EF. 2011. Carbon and nitrogen dynamics in an Oxisol as affected by liming and crop residues under no-till. Soil Science Society of America Journal 75: 1723–1730. [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Brück H, Sattelmacher B. 2002. Effects of supplied nitrogen form on growth and water uptake of French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plants. Plant and Soil 239: 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison KA, Bol R, Bardgett RD. 2007. Preferences for different nitrogen forms by coexisting plant species and soil microbes. Ecology 88: 989–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsinger P, Plassard C, Tang C, Jaillard B. 2003. Origins of root-mediated pH changes in the rhizosphere and their responses to environmental constraints: a review. Plant and Soil 248: 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge A, Robinson D, Fitter A. 2000. Are microorganisms more effective than plants at competing for nitrogen?Trends in Plant Science 5: 304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inselsbacher E, Umana NH-N, Stange FC et al. 2010. Short-term competition between crop plants and soil microbes for inorganic N fertilizer. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42: 360–372. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson DS, Brookes PC, Powlson DS. 2004. Measuring soil microbial biomass. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 36: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kaštovská E, Šantrůčková H. 2011. Comparison of uptake of different N forms by soil microorganisms and two wet-grassland plants: a pot study. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43: 1285–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyakov Y. 2002. Review: factors affecting rhizosphere priming effects. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 165: 382. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyakov Y, Cheng W. 2001. Photosynthesis controls of rhizosphere respiration and organic matter decomposition. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 33: 1915–1925. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyakov Y, Xu X. 2013. Competition between roots and microorganisms for nitrogen: mechanisms and ecological relevance. New Phytologist 198: 656–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzyakov Y, Friedel J, Stahr K. 2000. Review of mechanisms and quantification of priming effects. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 32: 1485–1498. [Google Scholar]

- Leifeld J, Zimmermann M, Fuhrer J. 2008. Simulating decomposition of labile soil organic carbon: effects of pH. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 40: 2948–2951. [Google Scholar]

- Liljeroth E, Kuikman P, Van Veen J. 1994. Carbon translocation to the rhizosphere of maize and wheat and influence on the turnover of native soil organic matter at different soil nitrogen levels. Plant and Soil 161: 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lipson D, Näsholm T. 2001. The unexpected versatility of plants: organic nitrogen use and availability in terrestrial ecosystems. Oecologia 128: 305–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Field CB, Jackson RB. 2006. Does nitrogen constrain carbon cycling, or does carbon input stimulate nitrogen cycling?Ecology 87: 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Durenkamp M, De Nobili M, Lin Q, Brookes P. 2011. Short term soil priming effects and the mineralisation of biochar following its incorporation to soils of different pH. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43: 2304–2314. [Google Scholar]

- Malhi S, Nyborg M, Harapiak J, Flore N. 1991. Acidification of soil in Alberta by nitrogen fertilizers applied to bromegrass. In Plant-Soil Interactions at Low pH. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Malhi S, Nyborg M, Harapiak J, Heier K, Flore N. 1997. Increasing organic C and N in soil under bromegrass with long-term N fertilization. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 49: 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Martins-Loucao MA, Cruz C, Correia PM. 2000. New approaches to enhanced ammonium assimilation in plants. In Nitrogen in a Sustainable Ecosystem–From the Cell to the Plant. Eds. MA Martins-Loução and SH Lips. Leiden: Backhuy. [Google Scholar]

- Mary B, Mariotti A, Morel J. 1992. Use of 13C variations at natural abundance for studying the biodegradation of root mucilage, roots and glucose in soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 24: 1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew D, Malhi S. 1992. Long-term N fertilization of a solonetzic soil: effects on chemical and biological properties. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 24: 619–623. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CJ, Baggs EM, Morley N, Wall DP, Paterson E. 2015. Rhizosphere priming can promote mobilisation of N-rich compounds from soil organic matter. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 81: 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Nang SA, Butterly CR, Sale PWG, Tang C. 2017. Residue addition and liming history interactively enhance mineralization of native organic carbon in acid soils. Biology and Fertility of Soils 53: 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Norton JM, Firestone MK. 1996. N dynamics in the rhizosphere of Pinus ponderosa seedlings. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 28: 351–362. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RP, Finzi AC, Bernhardt ES. 2011. Enhanced root exudation induces microbial feedbacks to N cycling in a pine forest under long-term CO2 fumigation. Ecology Letters 14: 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelo LW, Munch JC. 2005. Microbial immobilisation and turnover of 13C labelled substrates in two arable soils under field and laboratory conditions. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 37: 2263–2272. [Google Scholar]

- Pietri JA, Brookes P. 2008. Relationships between soil pH and microbial properties in a UK arable soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 40: 1856–1861. [Google Scholar]

- Raab TK, Terry N. 1994. Nitrogen source regulation of growth and photosynthesis in Beta vulgaris L. Plant Physiology 105: 1159–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez KS, Craine JM, Fierer N. 2010. Nitrogen fertilization inhibits soil microbial respiration regardless of the form of nitrogen applied. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 42: 2336–2338. [Google Scholar]

- Rousk K, Michelsen A, Rousk J. 2016. Microbial control of soil organic matter mineralization responses to labile carbon in subarctic climate change treatments. Global Change biology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukshana F, Butterly C, Baldock J, Xu J, Tang C. 2012. Model organic compounds differ in priming effects on alkalinity release in soils through carbon and nitrogen mineralisation. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 51: 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Silsbury J, Catchpoole D, Wallace W. 1986. Effects of nitrate and ammonium on nitrogenase (C2H2 reduction) activity of swards of subterranean clover, Trifolium subterraneum L. Functional Plant Biology 13: 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- Song M, Xu X, Hu Q, Tian Y, Ouyang H, Zhou C. 2007. Interactions of plant species mediated plant competition for inorganic nitrogen with soil microorganisms in an alpine meadow. Plant and Soil 297: 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Svenning MM, Junttila O, Macduff JH. 1996. Differential rates of inhibition of N2 fixation by sustained low concentrations of NH4+ and NO3− in northern ecotypes of white clover (Trifolium repens L.). Journal of Experimental Botany 47: 729–738. [Google Scholar]

- Tang C, Unkovich M, Bowden J. 1999. Factors affecting soil acidification under legumes. III. Acid production by N2-fixing legumes as influenced by nitrate supply. New Phytologist 143: 513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C, Drevon J, Jaillard B, Souche G, Hinsinger P. 2004. Proton release of two genotypes of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) as affected by N nutrition and P deficiency. Plant and Soil 260: 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vance E, Brookes P, Jenkinson D. 1987a. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 19: 703–707. [Google Scholar]

- Vance E, Brookes P, Jenkinson D. 1987b. Microbial biomass measurements in forest soils: the use of the chloroform fumigation-incubation method in strongly acid soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 19: 697–702. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Tang C, Severi J, Butterly C, Baldock J. 2016. Rhizosphere priming effect on soil organic carbon decomposition under plant species differing in soil acidification and root exudation. New Phytologist 211: 864–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z-H, Raven JA. 1998. Influences of different nitrogen sources on nitrogen-and water-use efficiency, and carbon isotope discrimination, in C3 Triticum aestivum L. and C4 Zea mays L. plants. Planta 205: 574–580. [Google Scholar]

- Zak DR, Pregitzer KS, King JS, Holmes WE. 2000. Elevated atmospheric CO2, fine roots and the response of soil microorganisms: a review and hypothesis. New Phytologist 147: 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang S. 2012. Effects of NH4+ and NO3− on litter and soil organic carbon decomposition in a Chinese fir plantation forest in South China. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 47: 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, Cheng W. 2011. Rhizosphere priming effect increases the temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter decomposition. Global Change Biology 17: 2172–2183. [Google Scholar]