Abstract

Objectives

Exposure to suffering of a relative or friend increases the risk for psychological and physical morbidity. However, little is known about the mechanisms that account for this effect. We test a theoretical model that identifies intrusive thoughts as a mediator of the relation between perceived physical and psychological suffering of the care recipient and caregiver depression. We also assess the role of compassion as a moderator of the relation between perceived suffering and intrusive thoughts.

Methods

Hispanic and African American caregivers (N = 108) of persons with dementia were assessed three times within a one-year period. Using multilevel modeling, we assessed the mediating role of intrusive thoughts in the relation between perceived physical and psychological suffering and CG depression, and we tested moderated mediation to assess the role of caregiver compassion in the relation between perceived suffering and intrusive thoughts.

Results

The effects of perceived physical suffering on depression were completely mediated through intrusive thoughts, and compassion moderated the relation between physical suffering and intrusive thoughts. Caregivers who had greater compassion reported more intrusive thoughts even when perceived physical suffering of the CR was low. For perceived psychological suffering, the effects of suffering on depression were partially mediated through intrusive thoughts.

Discussion

Understanding the role of intrusive thoughts and compassion in familial relationships provides new insights into mechanisms driving caregiver well-being and presents new opportunities for intervention.

Keywords: Family caregiving, compassion, intrusive thoughts, depression

Introduction

Family caregivers shoulder the vast majority of long-term care responsibilities for the nearly one billion persons with disability worldwide. The majority of these individuals, particularly those with moderate-to-severe disability, are over the age of 60 (Viana et al., 2013). While the contribution of family caregivers to the well-being of their older relatives represents an enormous benefit to society by sparing professional and economic resources, it may also cause negative consequences for caregivers, including opportunity costs or foregone income, reduced quality of life, and increased stress-related health effects (Gitlin & Schulz, 2012). Explanatory models linking caregiver outcomes with features of the caregiving experience typically focus on the functional disability of the care recipient and the pragmatic challenges of providing care. In contrast to this view, we focus attention on exposure to suffering as a key contributing factor to caregiver health (Schulz et al., 2007).

Witnessing the suffering of a chronically ill relative or friend can take an emotional toll on a person, increasing his or her risk for psychological and physical morbidity (Monin & Schulz, 2009; Monin, Schulz, Martire, et al., 2010; Schulz et al., 2007). Data collected during the last 10 years has supported our views on suffering and compassion in family caregiving relationships. In one of our early explorations of this issue, we showed that that perceived patient suffering independently (controlling for care recipient disability and amount of care provided) contributed to caregiver depression in a sample of 1222 caregivers of dementia patients (Schulz et al., 2008). In a second study, we showed in a sample of 1330 older married couples that controlling for known risk factors for depression, there was a dose–response relationship between suffering in a spouse and concurrent depression in their partner, and controlling for sub-clinical cardiovascular disease (CVD) at baseline, husbands whose wives reported high levels of suffering also had higher rates of incident CVD (Schulz et al., 2009). Experimental laboratory research also showed that spouses' blood pressure and heart rate increased when watching and talking about their partners' suffering compared to the control conditions where they observed no suffering, a stranger suffering, or talked about having a meal with their partner (Monin, Schulz, Martire, et al., 2010).

Individual differences such as attachment style and marital satisfaction also affect how caregivers perceive and respond emotionally to partner suffering. For example, people who are insecurely attached to their relationship partners perceive and react differently to their partner's suffering than individuals who feel securely attached to close partners (Monin, Schulz, Feeney, & Cook, 2010). Using attachment theory as a framework (Bowlby, 1982) we have shown that caregivers who are more anxiously attached (i.e. worry about receiving care and love from others) perceive more suffering in their partners and experience more feelings of personal distress compared to caregivers who are less anxiously attached. In contrast, caregivers who have more avoidant attachments (i.e. they are uncomfortable with intimacy and dependence on others) report feeling less personal distress, but not lower perceptions of partner suffering, than caregivers with less avoidant attachments. In a daily diary study of spouses of individuals with chronic pain, we found that spouses who report high marital satisfaction report more distress in response to perceptions of partner suffering than spouses who report lower marital satisfaction (Monin, Levy, & Kane, 2015).

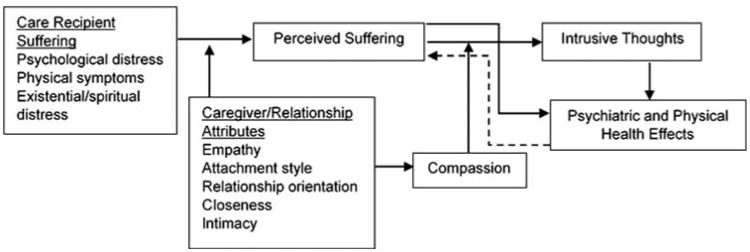

Refining the caregiver suffering-compassion model

More recently, we have refined our view about the role of suffering and compassion in family–caregiver relationships (Figure 1). Existing studies show that the perceived suffering of the care recipient is moderated by a number of caregiver attributes, including attachment style, marital satisfaction, and closeness (Monin, Schulz, Feeney, et al., 2010; Monin et al., 2015). As illustrated in Figure 1, these factors affect the perception of suffering and the consequent well-being of the caregiver. In this paper we expand on this model and examine the role of intrusive thoughts and compassion as predictors of caregiver well-being.

Figure 1.

The role of compassion in caregiver response to care recipient suffering.

The model makes two specific predictions about the role of intrusive thoughts and compassion. First, we hypothesize that the effects of perceived suffering are in part mediated through intrusive thoughts, the inability of the caregiver to avoid thinking about the state of the care recipient. Positive associations between repetitive and unbidden thoughts about stressful events have been consistently reported for a variety of stressful situations (Horowitz, 1986; Horowitz, Bonanno, & Holen, 1993). These findings have led some researchers to suggest that intrusive thoughts play a causal role in the development or maintenance of negative emotions during stress (Lepore, 1997). Among caregivers, rumination about caregiving after death of the care recipient has been linked to poor bereavement outcomes (Robinson-Whelen, Tada, MacCallum, McGuire, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2001). Researchers have also shown that the ability to control upsetting thoughts is a key attribute of caregiver self-efficacy (Steffen, McKibbin, Zeiss, Gallagher-Thompson, & Bandura, 2002).

Second, compassion, in this model, is predicted to moderate the relation between perceived suffering and intrusive thoughts such that high levels of compassion increase intrusive thoughts which in turn increase negative health effects. Although there are many different definitions of compassion in the literature, we focus here on compassion in the context of caregiving and define it as a feeling that arises in witnessing another's suffering and that motivates a subsequent desire to help (Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010; Schulz et al., 2007). Compassion may play a critical role in a caregiving context where there are strong personal connections and shared worldviews between the caregiver and care recipient. We hypothesize that individuals who are highly compassionate, in comparison to individuals who are low in compassion, should be more sensitive to the suffering of the care recipient and find it more difficult to suppress thoughts about symptoms of suffering, consequently experiencing more depressive symptoms.

We explore these issues in a sample of minority caregivers who were enrolled in a caregiver intervention study (Czaja, Lowenstein, Schulz, Nair, & Perdomo, 2013). However, we did not predict differences between African Americans and Hispanics in response to the suffering of someone close to them; nor would we expect differences between minority and majority populations. The tendency to respond with compassion to the suffering of another, especially in familial relationships, we believe is a human universal because it helps assure the survival of successive generations of offspring. In a similar vein, intrusive thoughts play a critical and universal role in motivating humans to respond to the suffering of another.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 110 African American and Hispanic family caregivers of persons with dementia enrolled in a longitudinal caregiver intervention study (Czaja et al., 2013). Caregivers (CG) were recruited from memory disorder clinics, social service agencies, churches, community centers, and through newspaper advertisements and community presentations. Participants were required to be at least 21 years of age, residing with or sharing cooking facilities with the care recipient (CR), and providing care to them for a minimum of 4 hours per day for at least the past 6 months. The CRs were required to have a confirmed physician diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease (AD) or another type of dementia and a Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score less than 23 with at least one limitation in activities of daily living (ADLs) or two in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Other requirements included having a telephone, planning to remain in the geographic area for at least 6 months, and being competent in either English or Spanish. Participants were excluded if the caregiver or the CR had an illness or disability that would prohibit participation, or if the CR had an MMSE score of 0 and were bedbound. A total of 138 participants were screened in an initial telephone interview and 12 (9%) were found to be not eligible for the study and 16 participants (11.5%) refused to participate. A total of 110 participants were enrolled in the study at baseline; however, two participants had incomplete information on the key variables for this paper; thus, the analyses are based on 108 participants. Out of the 108 participants, 91 caregivers participated at the 5-month follow-up (15% attrition rate) and 73 caregivers participated at the 9-month follow-up (32% attrition rate). There were no significant differences at baseline in primary predictor or outcome variables between participants who remained in the study and those who were lost to follow-up.

Procedure

The study protocol and all study material were reviewed and approved by the University of Miami's institutional review board. After providing informed consent from caregivers and when possible CR, caregivers who met enrollment criteria were scheduled for a home visit where baseline assessment was administered by a trained assessor. As part of the study design, following this assessment 35% of the caregivers were randomly assigned to a technology-based multicomponent psychosocial intervention group modeled after REACH II (Belle et al., 2006; Czaja et al., 2013) and the remainder to a control condition receiving information only either via videophone or telephone or by mail. Another certified assessor blind to group assignment administered follow-up batteries at 5 months and 9 months after randomization into condition. All instruments were translated into Spanish using established techniques for forward and back translation. Bilingual staff conducted the assessments with Spanish-speaking participants.

Measures

Standard demographic data were collected on all participants and are presented in Table 1. At baseline, cognitive status of CR was assessed using the MMSE (Folstein et al., 1975). Impairments in daily functioning of CR were measured by a modified version of the six-item ADL Scale (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963) and the eight-item IADL Scale (Lawton & Brody, 1969).

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations for study variables by waves.

| Baseline (N = 108) | Follow-up 1 (N = 91) | Follow-up 2 (N = 73) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Depressive symptoms | 10.03 | 6.60 | 8.81 | 6.99 | 7.42 | 5.42 |

| Physical suffering | 8.18 | 4.40 | 8.27 | 4.35 | 7.85 | 3.96 |

| Psychological suffering | 13.08 | 8.54 | 12.94 | 8.54 | 12.19 | 8.11 |

| Intrusive thoughts | 10.21 | 5.58 | 9.65 | 5.94 | 8.78 | 5.42 |

| Compassion | 43.38 | 6.57 | 42.96 | 6.48 | 42.84 | 6.68 |

| intervention (1 = Intervention) | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.47 |

| Baseline MMSE | 11.22 | 7.80 | 11.71 | 7.64 | 12.21 | 7.71 |

| Baseline CG age | 61.00 | 12.90 | 60.24 | 13.16 | 61.74 | 12.61 |

| Baseline CG education | 2.70 | 1.33 | 2.74 | 1.33 | 2.81 | 1.35 |

| Baseline IADL | 6.23 | 1.68 | 6.24 | 1.75 | 6.01 | 1.78 |

| Baseline ADL | 3.74 | 2.18 | 3.62 | 2.14 | 3.36 | 2.16 |

| Caregiver Sex (1 = Female) | 0.81 | 0.40 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.82 | 0.39 |

| Race (1 = African American) | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.50 |

Depressive symptoms

Caregiver depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-S-10; Andresen, Malmgren, Carter, & Patrick, 1994). Caregivers reported the frequency with which they experienced each of the 10 symptoms over the past week using a scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). An overall depressive symptom score was computed by summing scores across all the items, with higher scores indicating increased presence of depressive symptoms (range = 0–30; baseline α = 0.84). Although researchers use different cut scores to characterize individuals as being at risk for clinical depression, there is a general consensus that a score of 10 or higher reflects clinically significant symptoms of depression (Andresen et al., 1994).

Physical and psychological suffering

Caregiver's perception of the care recipient's suffering of physical symptoms was assessed using nine items (Schulz et al., 2010). For each item, caregivers were asked to give their best estimate of how often the care recipient experienced each of the nine symptoms (e.g. shortness of breath, pain, nausea, lack of energy/fatigue) during the past week along a 4-point scale from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Very often/Every day). Physical suffering score was computed by summing scores across all the items, with higher scores indicating higher perceived physical suffering (range = 0–27; baseline α = 0.64). Caregiver's perception of the care recipient's suffering of psychological symptoms was assessed using 15 items (Schulz et al., 2010). For each item caregivers were asked how often the care recipient had experienced each of the 15 feelings (e.g. afraid, depressed, hopeless) during the past week along the same 4-point rating scale. Psychological suffering score was computed by summing across all 15 items, with higher scores indicating higher perceived psychological suffering (range = 0–45; α = .89).

Intrusive thoughts

Caregivers completed a seven-item intrusive thoughts scale adapted from the Impact of Event Scales (IES; Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979). This scale assesses the extent to which caregivers were unable to inhibit thoughts about the Care recipient's illness (e.g. ‘I thought about the Care recipient's illness when I did not mean to’; ‘I had trouble falling asleep or staying asleep because of pictures or thoughts about the Care recipient's illness that came into my mind’; ‘Other things kept making me think about the Care recipient's illness’; ‘I had dreams about the Care recipient's illness’). Responses ranged from 0 = Not at all to 3 = Often. The scores of the seven items were summed, with a higher score indicating inability to shutdown intrusive thoughts about Care recipient's suffering (range = 0–21; baseline α = 0.87).

Compassion

Although there are numerous instruments available for assessing compassion we selected one specifically adapted for measuring compassion in close personal relationships (Feeney & Collins, 2001, 2003). This scale consists of 11 items asking caregivers the extent to which they agree or disagree feeling compassion for the Care recipient (e.g. ‘It is difficult for me to see my partner/relative suffer’; ‘It is important for me to try to do everything possible to help reduce the suffering of my partner/relative’; ‘To some extent I “feel” the suffering of my partner/relative’). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree and were reverse-coded and summed to create a total score, higher score indicating higher compassion (range = 11–55; baseline α = .79).

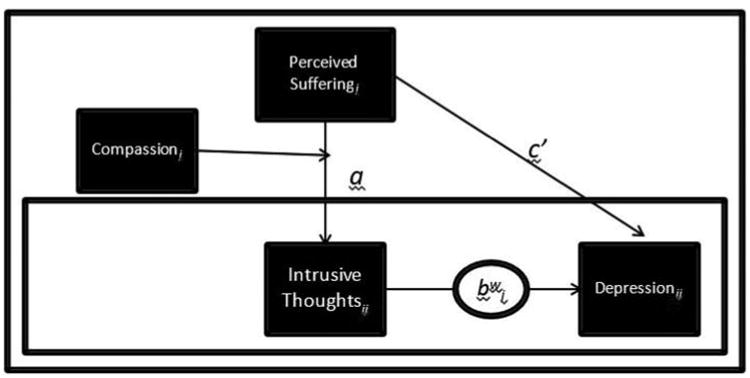

Analytic approach

The hypothesized model we proposed represents a moderated mediation model in which two predictor variables (in our case: perceived suffering and compassion) interactively affect a mediator (i.e. intrusive thoughts), which in turn influences the outcome, depressive thoughts (Figure 2). Given the study design wherein data was collected at three time points, we utilized the procedures outlined by Preacher, Zyphur, and Zhang (2010) for a 2-1-1 multilevel mediation model combined with the procedures of Bauer, Preacher, and Gil (2006) to test moderated mediation. These models enable us to concurrently examine the chain of effects between perceived physical or psychological suffering at Baseline (Level-2 predictor), and depressive symptoms measured at multiple time points (Level-1 predictor), including the mediating role of intrusive thoughts also measured at multiple time points (Level-1 predictor). Thus the simultaneous model is expressed at Level-1 as:

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of the role of intrusive thoughts and compassion on depressive symptoms.

where an intercept for M and Y and a within-person effect of M on Y (shown as bw in Figure 1) is estimated. The Level-2 model is expressed as

which estimates a random M intercept from X (shown as path a in Figure 2), a random Y intercept from X (shown as path c′) and the M intercept for level-2 unit j (a between-person effect of M on Y shown as bb). The within-person effect of M on Y was allowed to vary between waves. The effects of time-invariant control variables measured at baseline, such as caregiver's age, sex, education, race, and intervention condition, were also estimated at Level-2. Care recipient's MMSE score, IADLs, and ADLs collected at baseline were also included as Level-2 covariates.

To determine whether physical or psychological suffering was associated with greater intrusive thoughts for CGs who had higher compassion versus CGs who had lower compassion, we included a main effect of compassion and an interaction effect, i.e. Compassion × Physical Symptoms, also known as first-stage moderation effect, i.e. moderation of the first causal path (Hayes, 2015). The variables involved in the interaction term were grand-mean centered because we were interested in representing the CG's compassion relative to other caregivers in the study and not the deviation of each individual's compassion score relative to their own mean (Ryu, 2015). Moderation effects with other causal paths were also tested, but were trimmed when they were not found to have a significant association. A simultaneous mediation path was also tested. Mediation was indicated by: (1) a significant drop in the direct effects of suffering on depressive symptoms (the c′ path) when intrusive thoughts as a mediator was added to the model; and (2) a significant a*b indirect path, where a was the effect of perceived suffering on the person-specific average intrusive thoughts across time points, b was the sum of the effect of intrusive thoughts on depressive symptoms at the between-person level (bb), plus the within-person effect of intrusive thoughts on depressive symptoms (bw). Once all the parameters were estimated, a Monte Carlo confidence interval (CI) for the indirect effects based on 100,000 replications was generated (Preacher & Selig, 2012). The multilevel mediation models were estimated in MPlus (version 7). Full-information maximum likelihood estimation was employed to handle missing data which enables MPlus to use all available data points, even for cases with some missing responses. Similar analyses were run for perceived psychological suffering as the independent variable in the model.

Results

Participant characteristics across the three waves are presented in Table 1. Multilevel models that examined change over time on the key study variables found that there was a significant change in depressive symptoms (b = −0.86, SE = 0.37, p < 0.05) and intrusive thoughts (b = −0.62, SE = 0.36, p < 0.05) over the three waves, but no group × time differences were found between the intervention and control group. Moreover, there was no significant change in physical (b = −0.40, SE = 0.21, ns) or psychological suffering (b = −0.35, SE = 0.40, ns) over the three waves; hence, baseline scores on these variables were used for the rest of the analyses.

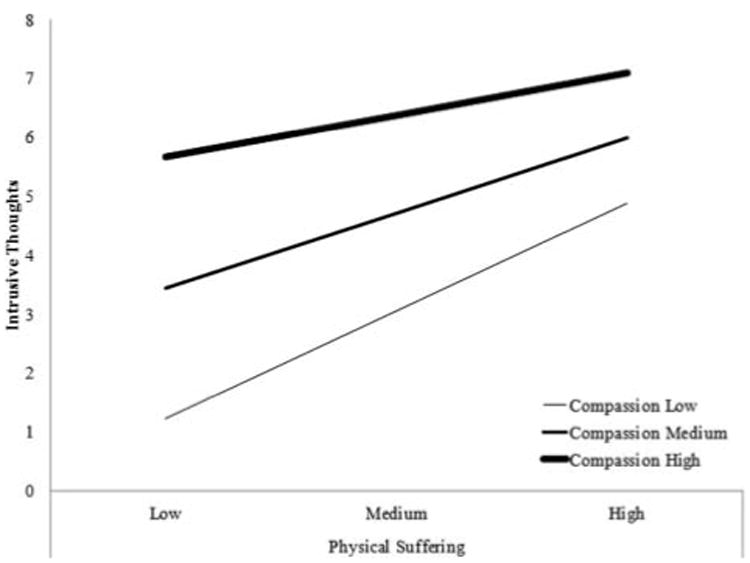

Next, the direct effects of physical symptoms and psychological symptoms on total CES-D-10 scores (without a mediator), controlling for other covariates in the model was assessed. Results indicated that depressive symptoms increased significantly when CGs perceived higher physical suffering (b = 0.33, SE = 0.09, p < 0.01) and higher psychological suffering (b = 0.23, SE = 0.05, p < 0.01). Our next model simultaneously examined the moderating effects of compassion on intrusive thoughts and the mediating effects of intrusive thoughts on depressive symptoms. Table 2 shows the results of the model with perceived physical suffering. Caregivers who perceived greater physical suffering at baseline also experienced higher intrusive thoughts on average (b = 0.39, p < 0.05). The main effect of compassion on intrusive thoughts (b = 0.19, p < 0.05) and the interaction effect between physical suffering and compassion on intrusive thoughts (b = −0.02, p < 0.05) were both found to be significant, suggesting that CGs who had greater compassion, compared to CGs who had lower compassion, were more likely to experience greater intrusive thoughts, even when they perceived low physical suffering (see Figure 3). The moderating effects on the other two causal paths were also tested, but were found to be not significant and hence trimmed from the model.

Table 2.

Multilevel moderated-mediation analyses showing association between physical suffering and depressive symptoms through intrusive thoughts (Ndata-points = 272; NCGs = 108).

| Intrusive thoughts Coeff (SE) [95% C.I.] | Depressive symptoms Coeff (SE) [95% C.I.] | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.79 (4.42) [−2.48, 12.07] | 2.44 (5.23) [−6.16, 11.04] |

| Physical suffering | 0.39 (0.08)** [0.25,0.52] | 0.07 (0.19) [−0.24, 0.38] |

| Between-person intrusive thoughts (bb) | - | 0.27 (0.24) [−0.13, 0.67] |

| Within-person intrusive thoughts (bw) | - | 0.34 (0.07) * [0.23,0.46] |

| Compassion | 0.19 (0.06) ** [0.08,0.30] | - |

| Physical suffering × compassion | −0.02 (0.01) * [−0.04, −0.004] | - |

| Control variables | ||

| Intervention group (1 = intervention) | −0.84 (0.82) [−2.19, 0.52] | 0.20 (0.93) [−1.32, 1.72] |

| MMSE | −0.02 (0.07) [−0.13, 0.09] | 0.14 (0.07) [0.02, 0.26] |

| CG age | 0.07 (0.04) [0.003, 0.14] | −0.03 (0.05) [−0.11,0.05] |

| CG education | −0.04 (0.35) [−0.62, 0.54] | −0.37 (0.34) [−0.94, 0.19] |

| CG IADL | 0.11 (0.24) [−0.30, 0.51] | −0.10 (0.32) [−0.62, 0.42] |

| CG ADL | 0.07 (0.21) [−0.28, 0.42] | 0.30 (0.27) [−0.15, 0.74] |

| CG female | 1.40 (1.16) [−0.51, 3.31] | 2.93 (1.55) [0.38, 5.47] |

| CG race (AA D 1) | −1.25 (0.84) [−2.63, 0.14] | −1.75 (1.02) [−3.43, −0.08] |

| Direct effects (c′) | 0.07 (0.19) [−0.24, 0.38] | |

| Indirect effects [a(bb + bw)] | 0.24(0.10)** [0.07,0.41] | |

Note:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

Figure 3.

Highly compassionate caregivers experience more intrusive thoughts, even when exposure to physical suffering is low.

As described earlier, in multilevel models the effect of the mediating variable on the dependent variable has two components: a between-person (Level-2) effect and an average within-person effect (Level-1). Results of these two estimates suggest that the within-person effect was significant, but the between-person effect was not. This suggests that CGs who experienced relatively more intrusive thoughts than other caregivers did not necessarily experience more depressive symptoms (bb = 0.27, ns). However, waves in which caregivers experienced more intrusive thoughts they also experienced greater depressive symptoms (bw = 0.34, p < 0.01). Overall, a significant indirect effect of physical suffering on depression through intrusive thoughts and moderated by compassion was found (b = 0.24, p < 0.01) and the relationship of perceived physical suffering with depressive symptoms (the c path) was significantly reduced (from b = 0.33 to b = 0.07).

Table 3 shows the results of the model with perceived psychological suffering. CGs who perceived greater psychological suffering at baseline also experienced higher intrusive thoughts, on average (b = 0.14, p < 0.01). Although we found a significant main effect of compassion on intrusive thoughts (b = 0.21, p < 0.01), the moderating effect of compassion on the other three causal paths was found to be not significant, and was therefore trimmed from the model. The mediation paths showed that in waves CGs experienced relatively more intrusive thoughts, they also experienced greater depressive symptoms in those waves (bw = 0.33, p < 0.01); however, CGs who experienced more intrusive thoughts than other CGs did not experience more depressive symptoms relative to others (bb = 0.03, ns). The formal test of the indirect effect of psychological suffering on depression through intrusive thoughts was found to be significant (b = 0.06, p = 0.05); however, the direct effect on depressive symptoms was also significant (c′ = 0.22, p < 0.01), providing evidence of partial mediation. Older caregivers reported more depressive symptoms on average, whereas African American caregivers experienced fewer depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Multilevel mediation analyses showing association between psychological suffering and depressive symptoms through intrusive thoughts (Ndata-points = 272; NCGs = 108).

| Intrusive thoughts Coeff. (SE) [95% C.I.] | Depressive symptoms Coeff. (SE) [95% C.I.] | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.43 (4.52) [−3.00, 11.87] | 3.76 (4.63) [−3.86, 11.38] |

| Psychological suffering | 0.14(0.05)** [0.05, 0.22] | 0.22 (0.08) ** [0.09,0.35] |

| Between-person intrusive thoughts (bb) | 0.03 (0.19) [−0.30, 0.35] | |

| Within-person intrusive thoughts (bw) | 0.33 (0.07) ** [0.22,0.44] | |

| Compassion | 0.21 (0.08) ** [0.08, 0.33] | - |

| Control variables | ||

| Intervention group (1 = intervention) | −1.04 (0.84) [−2.42, 0.34] | −0.04 (0.86) [−1.45, 1.37] |

| MMSE | −0.02 (0.07) [−0.14, 0.10] | 0.10 (0.06) [−0.004, 0.21] |

| CG age | 0.06 (0.04) [−0.004, 0.13] | 0.00 (0.04) [−0.08, 0.07] |

| CG education | −0.12 (0.37) [−0.73, 0.49] | −0.40 (0.33) [−0.93, 0.14] |

| CG IADL | 0.16 (0.27) [−0.28, 0.61] | −0.08 (0.30) [−0.58, 0.42] |

| CG ADL | 0.21 (0.22) [−0.16, 0.57] | 0.27 (0.24) [−0.13, 0.67] |

| CG female | 1.51 (1.25) [−0.54, 3.57] | 2.94(1.29)* [0.82,5.05] |

| CG race (AA = 1) | −1.73(0.85)* [−3.13, −0.33] | −2.10 (0.96) * [−3.68, −0.52] |

| Direct effects (c′) | 0.22 (0.08) ** [0.09,0.35] | |

| Indirect effects a(bb + bw) | 0.06 (0.03) * [−0.002,0.10] | |

Note:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

We also explored the direct association between compassion (at baseline) and CG depression (CESD), which we found to be statistically significant. When we added the suffering variables to this model, the association between compassion and depression decreased. Further adding intrusive thoughts to the model (CESD = Suffering + Intrusive Thoughts + Compassion) caused the association between compassion and depression to become non-significant.

Discussion

Our goals in this study were to assess the role of intrusive thoughts as a mediator of the relation between perceived suffering of the CR and CG depression, and to examine the role of CG compassion as a moderator of the relation between perceived suffering and intrusive thoughts. We predicted that CGs high in compassion would experience more intrusive thoughts, which would in turn increase negative health effects. Using multilevel modeling, we found that the perceived physical and psychological suffering of the CR was significantly related to CG depression after controlling for CG demographics and CR functional status indicators. These findings are consistent with previous studies (Monin & Schulz, 2009). This study makes an important new contribution by showing that the effects of perceived physical suffering were mediated through intrusive thoughts and that compassion moderated the relation between physical suffering and intrusive thoughts. Caregivers who had greater compassion, were more likely to experience greater intrusive thoughts even when perceived physical suffering of the CR was low. For psychological suffering, we found significant direct effects of suffering on depression as well as significant mediated effects through intrusive thoughts, indicating partial mediation. However, compassion was not a significant moderator of the relation between psychological suffering and intrusive thoughts. The differential findings for physical and psychological symptoms of suffering suggest that physical symptoms may be more easily identified and therefore more susceptible to the influence of individual differences in compassion. Psychological symptoms may be more difficult to recognize and interpret, particularly in persons with dementia (Schulz et al., 2010).

From a clinical perspective, these findings suggest three potential targets for interventions: (1) strategies to alleviate care recipient suffering; (2) downregulating intrusive thoughts experienced by the caregiver, and (3) treating caregiver psychiatric health effects. First, developing interventions that address patient suffering should receive the highest priority because of their dual impact on the care recipient and caregiver. Current health and social service policy for family caregivers places a strong emphasis on interventions designed to facilitate care provision, which may address care recipient suffering. Multiple strategies can be used to alter care recipient suffering, including medical interventions, the use of assistive devices, providing emotional and instrumental support, and selecting activities and tasks that minimize suffering.

Second, the research reported here suggests that downregulating intrusive thoughts may be particularly important because of their association with depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and physical health. A variety of cognitive strategies can be used to minimize the downstream effects of intrusive thoughts, including mindfulness-based interventions to manage intrusive thoughts about suffering, and mitigate their effects on caregiver depression. Caregivers may also use emotional deployment strategies, shifting attention from suffering to unrelated thoughts or future activities, reappraise the situation by thinking about its positive aspects (e.g. ‘I'm doing something good for the care recipient’), putting the suffering in perspective (e.g. ‘my partner hurts now, but it won't last forever’), distancing themselves from the suffering (e.g. focusing on the medical aspects of the situation as a nurse or doctor would), or blaming the partner (e.g. ‘he knows he shouldn't be pushing himself that hard’; adapted from Gross, 2002). Strategies to promote engagement in pleasant activities may also help lessen the CGs intrusive thoughts as it may provide a respite or distraction from caregiving activities. Note that while all of these strategies tend to lessen the impact of exposure to suffering on the CG, they are not all equally beneficial to the CR. Strategies such as distancing oneself from or blaming the sufferer may serve to maintain or enhance the suffering of the care recipient.

Third, treating psychological health effects in caregivers such as depression may be beneficial because it decreases the perception of care recipient suffering. Research shows that caregivers who are depressed and in poor physical health have negatively biased perceptions of CR suffering (Schulz et al., 2013). Treating depression should reduce this bias and bring the caregivers perception more in line with reality. Effective caregiver intervention strategies for depression include using cognitive behavior therapy, pleasant events training, or relaxation exercises.

Our results also highlight the fact that compassion can be a risk factor for negative CG outcomes. High levels of compassion can increase intrusive thoughts, which can have a negative impact on psychological health. Although higher levels of caregiver compassion likely reflect a high-quality relationship with the care recipient and is an important factor in the caregiving process, there can be downsides to being a highly compassionate caregiver. Interventions that diminish the personal distress and feelings of enmeshment with the partner, but foster compassionate behavior may be helpful. For instance, mindfulness-based therapies that encourage psychological distance from a partner's suffering but redirect one's attention to tasks and activities focused on the goal of caring may be useful for highly compassionate individuals (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). It may also be useful to target for intervention those individuals who are very high in compassion to prevent future caregiver burnout.

Caution is advised in generalizing from this sample of caregivers because they agreed to enroll in an intervention study for caregivers. Although we were able to address issues of internal validity by controlling for group assignment in our analysis, the external validity of this study is limited by the non-representative nature of this relatively small sample. Our sample is also unique in that it is comprised exclusively of two minority groups, African Americans and Hispanics, limiting our ability to generalize to the majority white population or other cultural/ethnic groups. That said, we believe that the tendency to respond with compassion to the suffering of another, especially in familial relationships, is a human universal because it helps assure the survival of successive generations of offspring. In a similar vein, intrusive thoughts play a critical and universal role in motivating humans to respond to the suffering of another. As a result, we would not expect differences between African Americans and Hispanics in response to the suffering of someone close to them.

A second limitation of this study is that we used a role- and context-specific measure of compassion as opposed to a more general dispositional measure of this construct (Batson, Fultz, & Shoenrade, 1987). Although we would expect role-specific compassion to be associated with dispositional compassion, our data do not allow us to conclusively address this issue.

It is important to keep in mind as well that all of the data for this study were collected from the caregiver; thus, we are capturing the phenomenology of the caregiver, which may have only a moderate relation to the perspectives of the care recipient. For example, we have shown in other studies that caregivers tend to perceive higher levels of suffering in care recipients than reported by the care recipients themselves (Schulz et al., 2010).

Our goal in this paper has been to show how suffering, compassion, and intrusive thoughts are key features of the family caregiving experience. These constructs provide new insights into mechanisms driving caregiver well-being and present new opportunities for intervention.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Langeloth Foundation, Cisco Systems, AT&T, and the Administration on Aging.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: None of the authors of this paper have any interests or activities that might be seen as influencing the research (e.g. financial interests in a test or procedure, funding by pharmaceutical companies for research).

References

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, Fultz J, Shoenrade PA. Distress and empathy: Two qualitatively distinct vicarious emotions with different motivational consequences. Journal of Personality. 1987;55(11):19–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Preacher KJ, Gil KM. Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2006;11:142. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, Coon D, Czaja SJ, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Zhang S Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health (REACH) II Investigators. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: A randomized, controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(10):727–738. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1982;52(4):664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja SJ, Loewenstein D, Schulz R, Nair SN, Perdomo D. A videophone psychosocial intervention for dementia caregivers. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;21(11):1071–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC, Collins NL. Predictors of caregiving in adult intimate relationships: An attachment theoretical perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80(6):972–994. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.6.972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC, Collins NL. Motivations for caregiving in adult intimate relationships: Influences on caregiving behavior and relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29(8):950–968. doi: 10.1177/0146167203252807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3)(75):189–198. 90026–6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Schulz R. Family caregiving of older adults. In: Prohaska TR, Anderson LA, Binstock RH, editors. Public health for an aging society. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2012. pp. 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E. Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(3):351–374. doi: 10.1037/a0018807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology. 2002;39(3):281–291. doi: 10.1017/S0048577201393198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2015;50:1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MJ. Stress-response syndromes: A review of posttraumatic and adjustment disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1986;37(3):241–249. doi: 10.1176/ps.37.3.241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/ps.37.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MJ, Bonanno GA, Holen A. Pathological grief: Diagnosis and explanation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1993;55(3):260–273. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41(3):209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(2):144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged: The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ. Expressive writing moderates the relation between intrusive thoughts and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(5):1030–1037. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin JK, Levy BR, Kane HS. To love is to suffer: Older adults daily emotional contagion to perceived spousal suffering. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences. 2015 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv070. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin JK, Schulz R. Interpersonal effects of suffering in older adult caregiving relationships. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24(3):681–695. doi: 10.1037/a0016355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin JK, Schulz R, Feeney BC, Cook TB. Attachment insecurity and perceived partner suffering as predictors of personal distress. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46:1143–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin JK, Schulz R, Martire LM, Jennings JR, Hagerty Lingler J, Greenberg MS. Spouses' cardiovascular reactivity to their partners' suffering. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences. 2010;65B(2):195–201. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Selig JP. Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures. 2012;6:77–98. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2012.679848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, Zhang Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods. 2010;15(3):209–233. doi: 10.1037/a0020141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Whelen S, Tada Y, MacCallum RC, McGuire L, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Long-term caregiving: What happens when it ends? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(4):573–584. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.573. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.110.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu E. The role of centering for interaction of level 1 variables in multilevel structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2015;22(4):617–630. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.936491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR, Hebert RS, Martire LM, Monin JK, Tompkins CA, Albert SM. Spousal suffering and partner depression and cardiovascular disease: The cardiovascular health study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17(3):246–254. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318198775b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Cook TB, Beach SR, Lingler JH, Martire LM, Monin JK, Czaja SJ. Magnitude and causes of bias among family caregivers rating Alzheimer's disease patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Hebert RS, Dew MA, Brown SL, Scheier MF, Beach SR, et al. Nichols L. Patient suffering and caregiver compassion: New opportunities for research, practice, and policy. The Gerontologist. 2007;47(1):4–13. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, McGinnis KA, Zhang S, Martire LM, Hebert RS, Beach SR, et al. Belle SH. Dementia patient suffering and caregiver depression. Alzheimers Disease & Associated Disorders. 2008;22(2):170–176. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31816653cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Monin JK, Czaja SJ, Lingler J, Beach SR, Martire LM, et al. Cook TB. Measuring the experience and perception of suffering. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(6):774–784. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen AM, McKibbin C, Zeiss AM, Gallagher-Thompson D, Ban-dura A. The revised scale for caregiving self-efficacy: Reliability and validity studies. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences. 2002;57(1):P74–P86. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.P74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana MC, Gruber MJ, Shahly V, Alhamzawi A, Alonso J, Andrade LH, et al. Kessler RC. Family burden related to mental and physical disorders in the world: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2013;35(2):115–125. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2012-0919. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2012-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]