Abstract

BACKGROUND

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a syndrome encompassing the clinical expression of frontal or temporal lobe degeneration. The many clinical phenotypes of FTD include primary progressive aphasias and a more common frontotemporal degeneration with less marked language alteration but significant behavioral changes.

SUMMARY

This paper describes the clinical progression of neuropsychiatric symptoms among 62 predominantly behavioral presentations and 30 language presentations of FTD. Disinhibition and depression became common for both subject groups over the course of illness. Significantly more cases presenting with behavioral changes had apathy and disinhibition.

CONCLUSIONS

Language presentations of FTD had longer latency to onset of distinct neuropsychiatric changes but eventually converge with the phenotype initially affected with behavioral change. Clinicians should anticipate such neuropsychiatric changes, prepare families for the course of illness in patients with either clinical presentation, and treat symptomatically with psychotropic medications to help families cope with behaviorally disturbed patients.

Keywords: frontotemporal dementia, neuropsychiatry, Pick's disease, primary progressive aphasia, semantic dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a non-Alzheimer's type of dementia syndrome accounting for as many as 16% of dementia cases that go to autopsy (1). Frontotemporal dementia is a category of dementias encompassing numerous neurodegenerative disorders with a predilection for frontal or temporal lobes. Changes in the frontal lobes cause loss of organizational skills, impulsivity, poor judgment, marked changes in personality, and loss of language ability. Most cases are referred to as “Pick's disease,” although most patients do not have specific phenotype pathology at autopsy. Criteria for the diagnosis of FTD are listed in Table 1. The first two generations of diagnostic criteria (2,3) created expectations for neuropathological findings that have not been met. The recent recommendations from the Work Group on Fronto-temporal Dementia and Pick's Disease (4) simplify the clinical diagnostic categories to emphasize the postmortem neuro-pathological diagnoses.

Table 1.

Evolution of Criteria for the Clinical Diagnosis of Frontotemporal Dementia

| Lund and Manchester Criteria (3)—1994 |

Summary of Neary Criteria (2)—1998 | Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick's Disease (4)—2001 |

|---|---|---|

| Insidious onset with gradual progression (unlike vascular dementia) | ||

| No evidence of possible or probable Alzheimer's disease or stroke in dominant frontal lobe to explain the deficits below | ||

At least two of the following:

|

Three separate lists to describe each prototypic clinical syndrome:

|

The development of behavioral or cognitive deficits manifested by early and progressive change in either:

|

Supportive features which are generally detected in patients in moderate to end-stages of illness include:

|

Supportive features include list in first column. | |

Diagnostic exclusion features:

|

Substance-induced conditions, delirium, and psychiatric diagnoses are not primary etiologies for the above. Neuropathological diagnoses: Tau-positive inclusions

or Neither tau-positive inclusions nor insoluble tau

|

|

SAMPLE CASE 1 ILLUSTRATES A BEHAVIORAL PRESENTATION OF FTD

A.B. was a 71 year old, right-handed woman with chief complaints of behavioral and memory problems. She had onset at age 68 years of disinhibition, impulsivity in many areas, including spending money, flattened affect, and voracious appetite. As an example, she disrobed in public if feeling too hot.

A.B. had developed a new ritualistic behavior: on daily walks with her dog; she felt compelled to touch a particular tree. As the disease wore on, she began to peel bark off the same tree. Memory and concentration problems later developed. She had difficulty with learning and maintaining new appointments, handling complex tasks such as managing a checkbook, and cooking. Several years into illness, she had falls and urinary incontinence.

Past medical history was remarkable for heavy alcohol use for 20 to 30 years, including an arrest for “driving under the influence” and regular diazepam use, but discontinuation of both substances did not improve her cognition or behavior. A half-sister had Alzheimer's disease late in the eighth decade of life.

On examination three years into illness, the patient was awake, alert and attentive but with flat affect. She displayed utilization behavior (picking up items and using them although it was inappropriate during her medical appointment) and perseverations. Her speech had decreased output and limited responses and then declined to mutism in the 5th year of illness. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score 3 years into illness was 25/30. Abbreviated Boston Naming Test score was 13/15. The patient had decreased category and letter word fluency: 6 animals/min; 4 F-words/min. Digit span forward was normal (6), but the patient took 1 full minute to name months of the year in reverse and could not do it accurately. Memory testing with the 10-item auditory verbal learning test revealed a learning curve 3,4,5 word recollection over three trials; spontaneous recall of 4/10 words after a delay; and 10/10 word recognition, consistent with a retrieval type of memory deficit, as opposed to the amnestic disorder characteristic of Alzheimer's disease. Visuospatial testing revealed disorganization on copying three-dimensional sketches, but the patient copied overlapping pentagons and simple geometric shapes well.

On neurologic examination, she had motor impersistence, brisk but symmetric deep tendon reflexes, and a marked grasp reflex bilaterally.

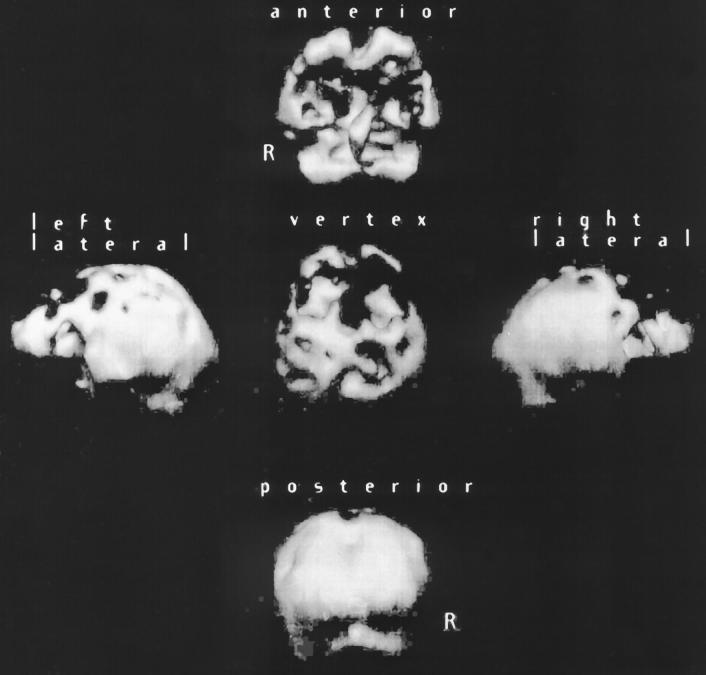

Structural neuroimaging showed bifrontal atrophy. Single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) scan of brain showed bifrontal hypoperfusion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sample case 1 with behavioral presentation of frontotemporal dementia: 3D reconstruction of HMPAO SPECT scan of brain shows bifrontal hypoperfusion.

SAMPLE CASE 2 ILLUSTRATES THE LANGUAGE PRESENTATION

Investigators agree that subjects with the language presentation have acquired progressive language deficits that dominate other cognitive deficits in severity, at least at the onset of cognitive impairment (5-17).

C.D. was a 68-year-old, right-handed man with chief complaint of word-finding problems. He had onset at age 59 years of difficulty with speech output. His family became alarmed when he was unable to lead prayers at a Jewish holiday dinner.

C.D.'s nonfluent speech worsened from little spontaneous output to stereotypic speech, “I don't know,” and relative mutism over 9 years. He withdrew from most activities, but it is difficult to tell whether this was because of the inability to communicate verbally or due to his moderate apraxia. In the 9th year of illness, he developed bowel and bladder incontinence and severe bruxism, but he still answered yes-no questions by nodding or shaking his head appropriately most of the time.

On examination, C.D. was awake, alert and attentive but with flat affect and was almost entirely nonverbal. He chewed gum constantly to avoid damaging his teeth with bruxism. He could not state his full name. He could neither participate in an MMSE nor point to pictures when given verbal cues. The patient was able to copy overlapping pentagons until seven years into illness. He had severe ideomotor apraxia nine years into illness.

On neurologic examination, C.D. developed flattening of the right nasolabial fold, decreased right armswing when walking, bilateral grasp reflex, and right extensor plantar response (Babinski sign) in the seventh year of illness.

Structural neuroimaging showed left frontal atrophy greater than right. Serial SPECT scans showed that hypoper-fusion was based at first in the left frontal lobe but then affected right frontal lobe significantly (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sample case 2 with language presentation of frontotemporal dementia: 3D reconstruction of HMPAO SPECT scan of brain shows left greater than right hypoperfusion, but right sided abnormality increased from Year 7 of illness (A) to Year 8 (B).

We monitor the neuropsychiatric symptoms of our subjects with both presentations of FTD regularly. This report is the first to compare the frequency of neuropsychiatric disturbances in behavioral versus language presentation groups of FTD.

METHODS

This sample includes cases identified from 1989 to 2000 at the UCLA Frontotemporal Dementia Clinic, the Harbor-UCLA Neurobehavior Clinic, and the UCSF Memory Disorders Clinic. We diagnosed subjects with behavioral or language presentation according to the criteria listed in Table 1, after mental status testing and neurologic examination, as in the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease protocol. Structural and functional neuroimaging-indicating more pathology in dominant frontal or temporal lobe supported the diagnosis of non-Alzheimer's FTD but was not available for all subjects. Two subjects had evidence of cerebral infarction on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain but the aphasia was progressive over time and the SPECT abnormalities could not be explained by stroke alone. Geschwind et al. previously reported the autopsy-confirmed diagnostic accuracy of FTD subjects identified through the UCLA Alzheimer's Disease Center at over 90% (18).

Demographic data about the subject and caregiver responses to the Neuropsychiatry Inventory (NPI) (19) were recorded. The NPI was repeated annually if subjects were available for follow-up.

We defined onset age as the earliest age at which the first symptoms were reported by either subject or caregiver. Histories of present illness provided data on behavioral changes at onset of illness, while the NPI supplied data specifying presence of apathy, dysphoric depression, and disinhibition. The NPI was performed on initial presentation to the clinic specializing in dementia and annually if the subject followed up at the clinic.

We compared the behavioral and language presentation groups using chi-squared testing to explore differences in gender and frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms at onset and later in the course of illness among the three diagnostic groups. T-tests compared mean ages at onset, mean educational levels, and time from onset of first symptom to diagnosis.

RESULTS

Among our sample of 62 patients with behavioral and 30 with language presentations, the two groups share similar gender distributions and mean levels of education. Non-White subjects constituted 4.8 to 6.7% of each FTD subgroup.

Mean age at onset of illness was significantly lower in behavioral presentation (μ 58 years, t = −2.8, two tailed P = 0.006), but language presentation subjects also had early onset ages (64 years). Time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis varied widely and did not differ significantly among the diagnostic groups. Childhood history of learning disorder was uncommon among all diagnostic categories.

Table 2 lists the frequency of neuropsychiatric symptoms in our sample. NPI data were available for only 48 of the behavioral presentation subjects. All subjects with language presentation had NPI data.Two of the 62 behavioral subjects had the motor neuron variant of FTD and earned the designation of “behavioral” because behavioral change was the initial symptom of illness. As expected from the diagnostic criteria, significantly fewer subjects with language presentation had neuropsychiatric symptoms at the onset of illness and over the course of illness. All but one of the behavioral presentation subjects developed behavioral disturbances within 2 years of manifesting cognitive dysfunction. Despite differences in initial presentation, the mean time to onset of first behavioral disturbances among subjects with positive NPI scores was similar for both groups. Over time, language presentation FTD subjects developed behavioral changes, although apathy and disinhibition occurred much more frequently among subjects with behavioral presentation (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Demographics and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Subjects with Frontotemporal Dementia

| Behavioral Presentation (n = 62) |

Language Presentation (n = 30) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Female | 51.6% | 47% |

| Mean years education, SD | 14.6, 3.4 | 14.5, 3.0 |

| Mean onset age (y, SD) | 58, 9.1* | 64.7, 9.8 |

| Mean delay to diagnosis in years, SD (range) | 5.4, 3.1 | 3.6, 1.9 |

| (1–33) | (0.5–9) | |

| Behavioral disturbance as initial symptom | 68.9%* | 36.7% |

| Dysphoric depressive symptoms at onset | 23% | 30% |

| Developed dysphoric depressive symptoms over course of illness | 32.3% | 43.4% |

| Mean yrs. to first behavioral disturbance, SD (range) | 0.84, 2.0 | 1.3, 2 |

| (0–33) | (0–10) | |

| Subjects without behavioral changes | 0 | 23.3%** |

| Apathy | 89.6% of 48** | 56.7% |

| Disinhibition | 68.8% of 48** | 53.3% |

Some data were missing for 24 of the subjects with behavioral presentation.

= P < .01

= P < .001

DISCUSSION

Subjects with behavioral presentation FTD had earlier onset of illness and earlier occurrence of behavioral disturbances than subjects with language presentation but neuro-psychiatric profiles for both presentations of FTD tended to converge by late stages of illness. Behavioral changes have not been reported widely in other case reports of PPA. Six of Kertesz' 16 PPA cases developed hyperorality, utilization behavior, aggressiveness, emotional flatness, and bizarre obsessive behavior, but timing of onset relative to aphasia was not reported (20). A case report on a Dutch man with semantic dementia described onset at age 50 and disinhibition as the only behavioral change 9 years into course of illness (12). Behavioral changes occurred most consistently in our behavioral presentation group, but depression, apathy, and disinhibition occurred with high frequency in both groups. As expected by the diagnostic criteria, more subjects with language presentation maintain normal behavior patterns in the first half of the illness than those with the behavioral presentation. The few subjects with language presentation who had severe behavioral disturbances manifested them fairly early in the course of illness. This may allow the clinician to inform family members of the expected course of illness, in the context of a 7 to 10 year survival with FTD.

These conclusions are based on cross-sectional data in which subjects had been followed over a range of 0 to 10 years into illness. Examination of longitudinal data might provide more complete prognoses and elicit risk factors for developing changes over time. The power of this type of study would be increased by autopsy-confirmed diagnoses.

SUMMARY

The most recently recommended clinical classification of FTD divides cases on the basis of neural systems most markedly impaired at presentation: behavior or language. Although disinhibition and other socially disruptive behaviors are not frequently seen early in the course of the primary progressive aphasias or the motorically affected cases of FTD, depression, apathy, and disinhibition should be anticipated in most patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has been funded by an Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (AG15670) grant from the National Institute on Aging, an Alzheimer's Disease Research Center of California grant, the Sidell-Kagan Foundation, and the Deane Johnson Foundation for Alzheimer's Disease Research. The authors thank Paula Mychak, PhD, for her assistance in collecting data for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brun A. Frontal lobe degeneration of non-Alzheimer type I. Neuropathol Arch Gerontol Geriatrics. 1987;6:193–208. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(87)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Lund and Manchester Groups Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:416–418. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.4.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, et al. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1803–1809. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.11.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caselli RJ, Windebank AJ, Petersen RC, et al. Rapidly progressive aphasic dementia and motor neuron disease. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:200–207. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graff-Radford NR, Damasio AR, Hyman BT, et al. Progressive aphasia in a patient with Pick's disease. Neurology. 1990;40:620–626. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lendon CL, Lynch T, Norton J, et al. Hereditary dysphasic disinhibtion dementia. A frontotemporal dementia linked to 17q21–22. Neurology. 1998;50:1546–1555. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris JC, Cole M, Banker BQ, et al. Hereditary dysphasic dementia and the Pick-Alzheimer spectrum. Ann Neurol. 1984;16:455–466. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otsuki M, Soma Y, Sato M, et al. Slowly progressive pure word deafness. Eur Neurol. 1998;39:135–140. doi: 10.1159/000007923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parkin AJ. Progressive aphasia without dementia. A clinical and cognitive neuropsychological analysis. Brain Lang. 1993;44:201–220. doi: 10.1006/brln.1993.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salmon E, Sadzot B, Maquet P, et al. Slowly progressive aphasia syndrome. A positron emission tomographic study. Acta Neurolog Belg. 1989;89:242–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheltens P, Hazenberg GJ, Lindeboom J, et al. A case of progressive aphasia without dementia: “temporal” Pick's disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:79–80. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sapin LR, Anderson FH, Pulaski PD. Progressive aphasia without dementia: further documentation. Ann Neurol. 1989;25:411–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.410250415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snowden JS, Neary D, Mann DM, et al. Progressive language disorder due to lobar atrophy. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:174–183. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tyrell PJ, Kartsounis LD, Frackowiak RSJ, et al. Progressive loss of speech output and orofacial dyspraxia associated with frontal lobe hypometabolism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:351–357. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.4.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mesulam M-M, Weintraub S. Spectrum of primary progressive aphasia. Bailliere's Clin Neurol. 1992;1:583–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weintraub S, Mesulam M-M. Four neuropsychological profiles in dementia. In: Boller F, Spinnler H, editors. Handbook of Neuropsychology. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1985. pp. 253–282. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geschwind D, Karrim J, Nelson SF, et al. The apolipoprotein E e4 allele is not a significant risk factor for frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:134–138. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kertesz A, Hudson L, Mackenzie IR, et al. The pathology and nosology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 1994;44:2065–2072. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.11.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]