Abstract

Purpose

Previous studies suggest that the adenosine receptor antagonist, 7-methylxanthine (7-MX), retards myopia progression. Our aim was to determine whether 7-MX alters the compensating refractive changes produced by defocus in rhesus monkeys.

Methods

Starting at age 3 weeks, monkeys were reared with −3 diopter (D; n = 10; 7-MX −3D/pl) or +3D (n = 6; 7-MX +3D/pl) spectacles over their treated eyes and zero-powered lenses over their fellow eyes. In addition, they were given 100 mg/kg of 7-MX orally twice daily throughout the lens-rearing period (age 147 ± 4 days). Comparison data were obtained from lens-reared controls (−3D/pl, n = 17; +3D/pl, n = 9) and normal monkeys (n = 37) maintained on a standard diet. Refractive status, corneal power, and axial dimensions were assessed biweekly.

Results

The −3D/pl and +3D/pl lens-reared controls developed compensating myopic (−2.10 ± 1.07 D) and hyperopic anisometropias (+1.86 ± 0.54 D), respectively. While the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys developed hyperopic anisometropias (+1.79 ± 1.11 D) that were similar to those observed in +3D/pl controls, the 7-MX −3D/pl animals did not consistently exhibit compensating myopia in their treated eyes and were on average isometropic (+0.35 ± 1.96 D). The median refractive errors for both eyes of the 7-MX −3D/pl (+5.47 D and +4.38 D) and 7-MX +3D/pl (+5.28 and +3.84 D) monkeys were significantly more hyperopic than that for normal monkeys (+2.47 D). These 7-MX–induced hyperopic ametropias were associated with shorter vitreous chambers and thicker choroids.

Conclusions

In primates, 7-MX reduced the axial myopia produced by hyperopic defocus, augmented hyperopic shifts in response to myopic defocus, and induced hyperopia in control eyes. The results suggest that 7-MX has therapeutic potential in efforts to slow myopia progression.

Keywords: myopia, hyperopia, emmetropization, 7-methylxanthine, adenosine receptors

Myopia is often considered to be a minor healthcare issue because the optical effects of myopia on visual acuity can usually be mitigated. However, myopia is a significant public health concern for a variety of reasons: (1) myopia is very common; globally it is the most frequent cause of reduced distance vision.1 (2) The prevalence of myopia is increasing in many areas around the world including East Asia,2–7 the United States,8–12 and other non-Asian countries.13–15 (3) The severity of myopia is rising; while the prevalence of moderate myopia doubled in the United States in the 30 years prior to 2000, myopia greater than 8 diopters (D) increased 8-fold.16 (4) Myopia is a leading cause of permanent visual loss.17 Because of structural changes associated with axial elongation,18 myopia, even in low amounts,19 poses an increased risk for cataract,20–22 glaucoma,23,24 chorioretinal degeneration, and retinal detachment.25–27 As a consequence, in parts of East Asia where the epidemic of myopia is advanced, myopic macular degeneration is now the most frequent cause of visual impairment.28–30 (5) Myopia carries a substantial economic burden. In addition to lost productivity, billions of dollars are spent annually on optical corrections and visual impairment caused by myopia.9,31–33 (6) Myopia can limit career choices and when uncorrected, as it frequently is,34,35 can interfere with learning. It is very likely that any treatment strategy that can effectively reduce the incidence and/or the progression of myopia would have a significant and positive public health impact.

A variety of optical treatment strategies have been shown to produce clinically meaningful reductions in myopia progression.36–38 However, these optical strategies typically do not completely arrest myopia progression. The muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine, can produce dramatic reductions in progression rates.39–41 However, the most effective concentrations of atropine (e.g., 0.1%, 0.5%, and 1%) can also produce ocular side effects that can, in some cases, compromise functional vision.42 In addition, at least with these higher concentrations, rebound effects have been observed following cessation of treatment.40,43 While low atropine concentrations (e.g., 0.01%) can minimize short-42,44 and potentially long-term side effects45 without rebound effects,43 the overall efficacy of such low atropine dosages in slowing myopic axial elongation has not been firmly established in either children43,46 or animals (Benavente-Perez A, et al. IOVS 2017;58:ARVO E-Abstract 5466; McFadden SA. IOVS 2017;58:ARVO E-Abstract 5467).

The nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist, 7-methylxanthine (7-MX), may provide an additional pharmaceutical treatment strategy for myopia. The initial interest in 7-MX as a potential therapeutic agent to slow myopia progression emerged from the observation that in contrast to the reduction in scleral collagen content and the decrease in collagen fibril diameter associated with myopic axial elongation,47,48 oral 7-MX increased the collagen-related amino acid content, the collagen fibril diameter, and the thickness of the posterior sclera in rabbits,49 presumably strengthening the sclera and reducing the potential for axial elongation.50 A subsequent pilot trial found that 7-MX was moderately effective in slowing axial elongation in myopic children.51 However, the sites and mechanisms of action of 7-MX are unknown.

Establishing an appropriate animal model for investigating the antimyopia effects of adenosine receptor antagonists is a critical step in refining key variables for clinical trials, evaluating safety issues, and identifying how adenosine antagonists influence refractive development. To date the observed effects of adenosine receptor antagonists on refractive development in animals have not been consistent. For instance in rabbits52 and guinea pigs,53 oral 7-MX reduced the degree of form-deprivation myopia by 18% and 46%, respectively (measured relative to fellow control eyes). However, in chickens, 7-MX did not significantly reduce the degree of form-deprivation myopia and only reduced the degree of myopia produced by hyperopic defocus by 23% (Wang K, et al. IOVS 2014;55:ARVO E-Abstract 3040). The purpose of this investigation was to characterize the effects of 7-MX on normal refractive development and vision-induced ametropias in infant rhesus monkeys.

We chose to investigate 7-MX because it does not have the arousal effects of other adenosine antagonists, such as caffeine, it has low toxicity,54,55 no carcinogenic effects,56 and there have been no reported adverse side effects in children in the previous pilot trials (Trier K, et al. IOVS 2017;58:ARVO E-Abstract 2385).51 In addition, 7-MX is a common and well-tolerated dietary ingredient. For instance, cacao is one of the most common dietary sources of 7-MX. Although cacao contains only minor amounts of 7-MX, it contains relatively large amounts of theobromine of which 7-MX is the main metabolite. For example, 50 g of dark chocolate contain 250 to 375 mg of theobromine.57 In humans, 36% of a dose of theobromine is excreted in the urine as 7-MX and, at any given point in time, the serum concentration of 7-MX is approximately 10% of that of theobromine.58

Rhesus monkeys were used in this study because the resulting data should be directly applicable to humans. Previous studies have shown a close correspondence, both qualitative and quantitative, between humans and macaques in the course of emmetropization,59–61 the changes in ocular components that occur during normal development,59,61,62 the alterations in ocular components that are associated with ametropias,63–65 and the effects of visual experience on refractive development.66,67

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The primary subjects were 16 rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) that were obtained at 2 to 3 weeks of age and reared in our nonhuman primate nursery. The ambient lighting was provided by fluorescent lights (correlated color temperature = 3500 K Philips TL735; Philips Lighting, Sommerset, NJ, USA) maintained on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle with the lights-on cycle starting at 7 AM. The average cage-level illuminance during the daily light cycle was 480 lux (range, 342–688 lux; for husbandry details see Smith and Hung65). Beginning at 24 ± 2 days of age, the experimental animals were fitted with light-weight goggles65,68–72 that secured either −3 D (n = 10) or +3 D spectacle lenses (n = 6) in front of their treated eyes and clear, zero-powered (“plano”) lenses in front of their fellow eyes, providing horizontal monocular and binocular fields of view of 80° and 62°, respectively, and an 87° vertical field. Except for brief periods needed for routine cleaning and maintenance, the lenses were worn continuously until 147 ± 4 days of age. Imposed defocus of ±3 D is well within the operating range of the emmetropization process in normal infant monkeys65,68 and the lens-rearing period was sufficiently long to ensure complete compensating growth for the degrees of imposed defocus.65

In addition to receiving the standard dietary regimen for infant monkeys, throughout the lens-rearing period, the experimental infants were fed by mouth 100 mg/kg of pharmaceutical grade 7-MX (V.B. Medicare Pvt. Ltd, Karnataka, India). The 7-MX was suspended in a small volume of infant formula or apple juice and administered orally twice daily (at 7:30 AM and 6:30 PM). Care was taken to ensure that the animals ingested all of the 7-MX prior to their normal feedings. Comparisons across previous animal studies suggested that lower dosages of 7-MX might not be effective in reducing vision-induced myopia (see the Discussion). Consequently, to reduce the potential for false negative results, we deliberately used a dosage of 7-MX that was approximately 3 times higher than that employed in any previous animal study and that was at least 6.5 times higher than that employed in earlier human studies. 7-MX has a relatively short half-life in the blood stream (∼200 minutes in adult humans51 and 1 hour in rabbits49). Consequently, the drug was administered twice each day to increase the daily duration of the drug exposure.

Comparison data, some of which were reported in previous publications, were obtained from infant monkeys that were reared with monocular −3 D (n = 17) or +3 D (n = 9) treatment lenses.65,68,71,73,74 The goggles, the control lenses for the fellow eyes, and the onset and duration of lens wear for the lens-reared controls were identical to those for the 7-MX–treated monkeys. Control data were also available for 37 infant monkeys that were reared with unrestricted vision.61,65,75–77 The rearing procedures, general husbandry protocols, and biometric measurement methods for the lens-reared and normal control animals were identical to those for the 7-MX–treated monkeys, except that they were not fed the adenosine receptor antagonist.

Ocular Biometry

The procedural details for measuring the eye's refractive status, corneal power, and axial dimensions have been described previously.65,68 Briefly, the monkeys were anesthetized (intramuscular injection: ketamine hydrochloride, 15–20 mg/kg, and acepromazine maleate, 0.15–0.2 mg/kg; topical: 0.5% tetracaine hydrochloride) and cycloplegia was induced by the instillation of 1% tropicamide 25 and 20 minutes prior to obtaining the measurements. The refractive state of each eye was measured independently by two experienced investigators using a streak retinoscope and averaged using matrix notation.78 An eye's refractive error was defined as the spherical-equivalent, spectacle-plane refractive correction (95% limits of agreement = ±0.60 D).79 The anterior radius of curvature of the cornea was measured using a hand-held keratometer (Alcon Auto-keratometer; Alcon, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) or a corneal video topographer (EyeSys 2000; EyeSys vision, Inc., Houston, TX, USA) when the corneal power exceeded the measurement range of the keratometer. Three readings were taken with the hand-held keratometer and averaged to calculate the central corneal power using an assumed refractive index of 1.3375 (95% limits of agreement = +0.49 to −0.37 D for mean corneal power).80 Ocular dimensions were measured by A-scan ultrasonography using a 13-MHZ transducer (Image 2000; Mentor, Norwell, MA, USA); 10 separate measurements were averaged (95% limits of agreement for vitreous chamber depth = ±0.05 mm).65,76 The initial biometric measures were obtained at ages corresponding to the start of lens wear and every 2 weeks throughout the observation period.

For the 7-MX–treated monkeys and 6 untreated normal monkeys, choroidal thickness was measured with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT; Spectralis, Heidelberg, Germany), which has an axial resolution of 3.9 μm per pixel, approximately an order of magnitude finer than that obtained using high-resolution A-scan ultrasonography.81–84 For imaging, the animal's head was stabilized using a 5-way positioner (X, Y, Z, tip, and tilt) and gas permeable contact lenses were inserted to ensure good optical clarity. All scans were conducted between 9 and 11 AM to avoid potential confounding effects of diurnal variations in choroidal thickness.85 The OCT's scan pattern (30° × 25°) was centered and focused on the fovea and the instrument's enhanced depth imaging mode86 was used to improve the visibility of the choroidal-scleral border. Thirty-one horizontal scans were obtained using the instrument's highest resolution protocol resulting in B-scan images of 1536 × 496 pixels; only scans with a quality index of 20 dB or higher were analyzed. The instrument's auto rescan feature was employed to track anatomic features to ensure that all subsequent scans were performed at the same retinal location as the baseline measurements. The scan data were exported and analyzed using custom Matlab software (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA), which further enhanced the visibility of the choroidal-scleral interface. An experienced, masked observer manually segmented each scan to identify Bruch's membrane and the choroidal-scleral interface. The center of the fovea was identified as the deepest point in the foveal pit observed in the central scans. Our primary measure was subfoveal choroidal thickness, defined as the average thickness across 1.8- to 2.1-mm long segments centered on the foveal pit, after correction for lateral magnification. The 95% limits of agreement for between session comparisons in controls was −10.4 to +5.9 μm. The initial choroidal thickness measures were obtained at ages corresponding to the onset of lens wear; subsequent measures were obtained at several time points during the treatment period.

All rearing and experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Houston's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in compliance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab (Release 16.2.4; Minitab, Inc., State College, PA, USA) and Super ANOVA software (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA). At ages corresponding to the end of the treatment period, the distribution of refractive errors in normal monkeys is leptokurtic.61 Consequently, nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare the median end-of-treatment refractive errors between pairs of subject groups. Mixed-design ANOVAs, followed by unpaired t-tests with Greenhouse-Geisser (G-G) corrections for multiple testing, were used to compare the changes in refractive error, anisometropia, and choroidal thickness between groups that occurred during the lens-rearing period. Paired Student's t-tests were employed to examine the interocular differences in ocular parameters within a given subject group. One-way ANOVAs were used to examine between-group differences in ocular parameters at ages corresponding to the start and end of lens wear. The relationship between refractive error and choroidal thickness and the relationship between refractive error and the ratio between vitreous chamber depth and corneal radius were characterized using linear regression analyses.

Results

There was no evidence that the 7-MX treatment regimen produced any adverse side effects. During our routine biometric measures, we did not observe any abnormal ocular signs associated with the 7-MX treatments. The behaviors of the 7-MX–treated monkeys were observed multiple times each day during the treatment period and there were no discriminable differences between the 7-MX monkeys and the monkeys maintained on a standard diet. Over the course of the treatment period, weight gains were similar in the control (+0.66 ± 0.07 kg) and 7-MX–treated monkeys (+0.68 ± 0.08 kg; P = 0.45). Near the end of the lens-rearing period, blood samples were drawn from representative control and 7-MX–treated monkeys and complete blood counts and basic metabolic analyses were performed. Although infant monkeys in all groups showed systematic differences in comparisons to adults (e.g., slightly lower total protein levels and lower numbers and percentages of neutrophils), there were no systematic differences in the blood analyses between the control and 7-MX–treated monkeys. There were no interocular differences in IOP in either the treated or control animals (P = 0.56–0.93). The average and range of IOPs in the fellow eyes of the 7-MX monkeys (11.4 ± 1.6 and 8–14 mm Hg) measured near the end of the lens-rearing period were comparable to those in age-matched control animals (12.3 ± 2.6 mm Hg, P = 0.22; 9–17 mm Hg). The retinas of the 7-MX monkeys appeared normal during ophthalmoscopy and although the thickness of the various retinal layers were not quantified, visual inspection of the cross-sectional OCT images obtained at the end of the treatment period did not reveal any obvious alterations in retinal anatomy in either the lens-treated or fellow eyes of the 7-MX monkeys.

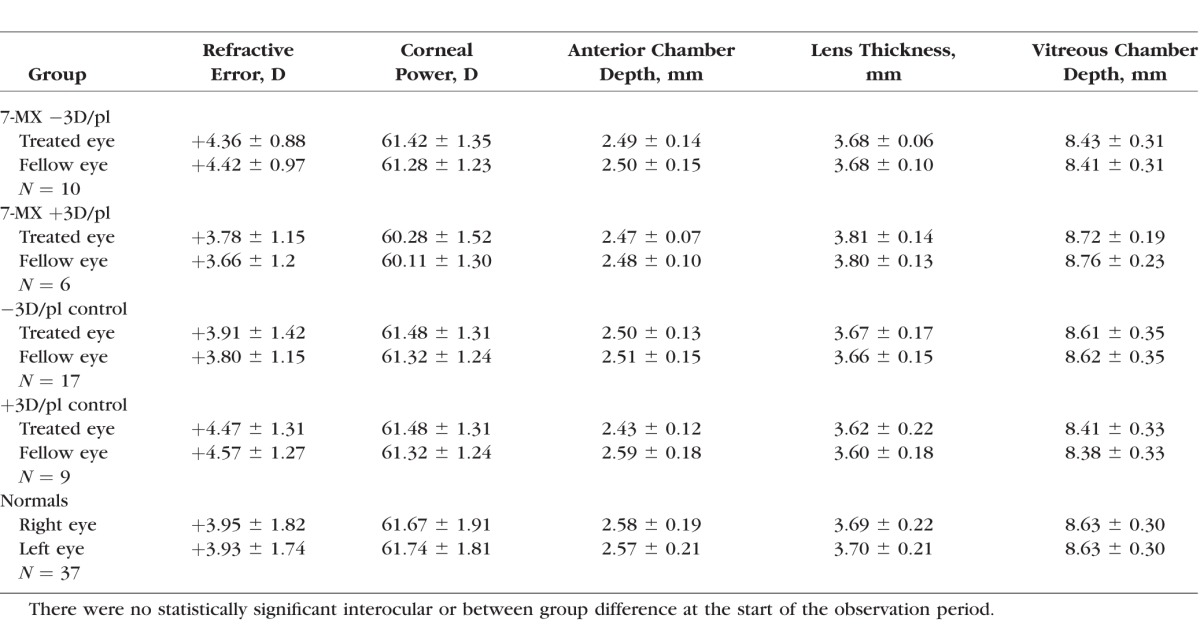

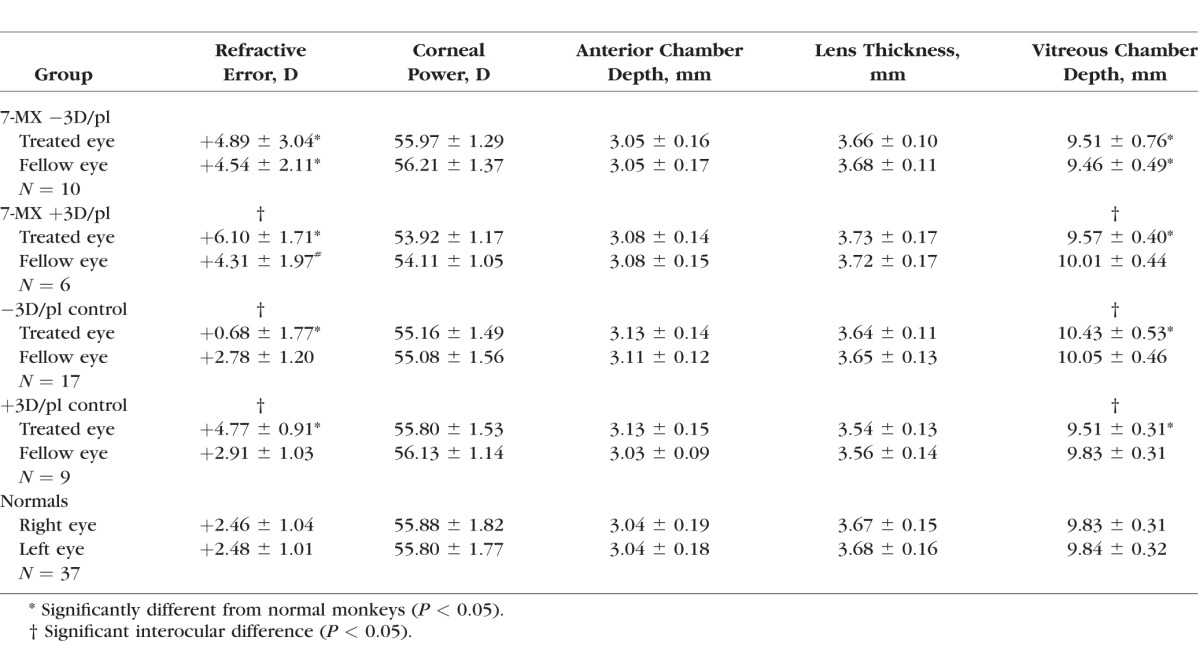

Baseline refractive and biometric measures for the 7-MX–treated animals are provided in Table 1. At the start of the lens-rearing period, the infant monkeys in the 7-MX groups exhibited the moderate degrees of hyperopia that are characteristic of age-matched normal monkeys and the corneal powers and axial dimensions in the 7-MX monkeys were similar to those in the lens-reared controls and normal monkeys (F = 0.46–2.01; P = 0.10–0.76; see Table 1). The refractive errors and ocular dimensions of the two eyes of the 7-MX monkeys were also well matched. There were no significant interocular differences in either 7-MX group in the average refractive errors, corneal powers, anterior chamber depths, lens thicknesses, or vitreous chamber depths (P = 0.09–0.95).

Table 1.

Average (±SD) Baseline Refractive and Biometric Measures

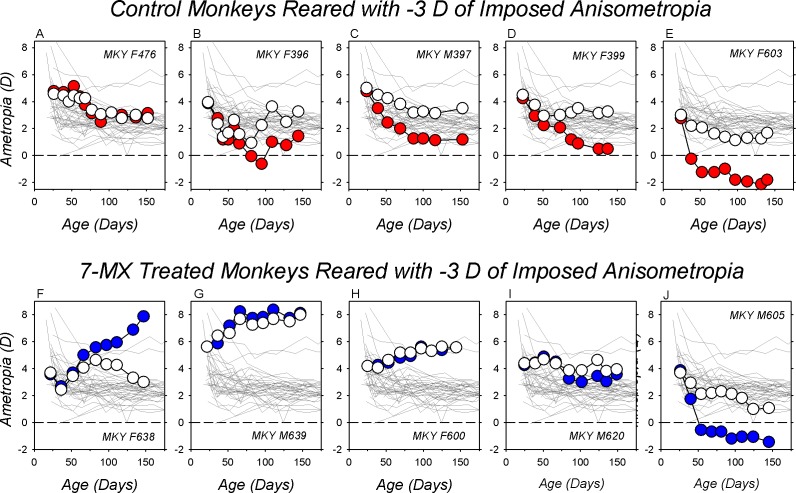

The effects of −3 D of optically imposed anisometropia on refractive development for representative lens-reared controls are illustrated in the top row of Figure 1. Spherical equivalent ametropias are plotted as a function of age for the treated (red symbols) and control eyes (white symbols) for five of 17 control animals reared with −3 D lenses in front of their treated eyes and plano lenses in front of their fellow eyes. These animals, which were selected to illustrate the range of compensating responses, are ordered in Figures 1A to 1E on the basis of the degree of myopic anisometropia exhibited at the end of the treatment period from the smallest (+0.38 D) to largest degrees of compensating anisometropia (−3.5 D). The animal in Figure 1C exhibited the median anisometropia for the group (−2.31 D). The key point of the data included in the top row of Figure 1 is that −3 D of imposed monocular hyperopic defocus consistently produced relative myopic shifts in the treated eyes resulting in a compensating myopic anisometropia. Only one of 17 −3D/pl control animals failed to manifest a myopic anisometropia of at least 1.0 D after approximately 100 days of age.

Figure 1.

Spherical-equivalent, spectacle-plane refractive corrections plotted as a function of age for the treated (filled symbols) and fellow eyes (open symbols) of representative lens-reared controls (top row) and 7-MX–treated monkeys (bottom row). All of the animals were reared with −3.0 D lenses in front of their treated eyes and plano lenses in front of their fellow eyes. The thin gray lines in each plot represent data for the right eyes of the 37 normal control monkeys. The panels in each row are arranged from left to right according to the maximum degree of myopic anisometropia at the end of the lens-rearing period. The monkeys represented in panels (A, F and E, J) exhibited the smallest and largest degrees of myopic anisometropia, respectively. The monkeys in panels (C, H) exhibited the median degree of myopic anisometropia in their respective group.

As illustrated in the bottom row of Figure 1, which shows longitudinal treated- (blue symbols) and control eye ametropias (white symbols) for five of 10 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys, oral administration of 7-MX greatly reduced the likelihood that an animal would compensate for the imposed monocular hyperopic defocus. Only three of 10 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys showed any signs of compensating myopic anisometropias (Figs. 1I, 1J). Five of 10 7-MX–treated monkeys exhibited hyperopic shifts in the refractive errors of both eyes, but remained isometropic throughout the lens-rearing period (Figs. 1G, 1H). Interestingly, two of the 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys developed substantial degrees of relative hyperopia in their treated eyes (Fig. 1F), which effectively increased the degree of hyperopic defocus that these animals experienced during the lens-rearing period. Other than the relative hyperopic anisometropias, there was nothing unusual in the histories of these two animals that would distinguish them from the other eight 7-MX −3D/pl animals.

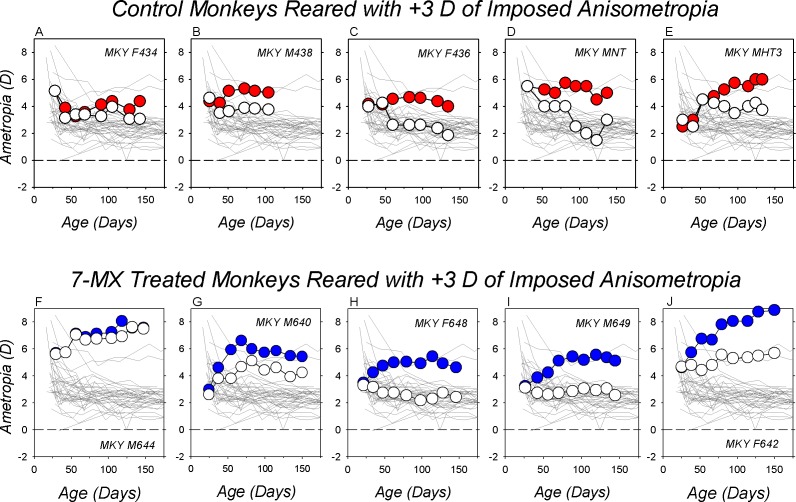

As illustrated in Figure 2, which shows data for five representative +3D/pl controls, rearing animals with +3 D of optically imposed anisometropia consistently produced compensating hyperopic anisometropias (top row). All nine of the +3 D lens-reared controls developed relative hyperopic refractions in their treated eyes (red symbols). At the end of the lens-rearing period, the degree of anisometropia varied from +1.25 D (Fig. 2A) to +2.25 D (Fig. 3E).

Figure 2.

Spherical-equivalent, spectacle-plane refractive corrections plotted as a function of age for the treated (filled symbols) and fellow eyes (open symbols) of representative lens-reared controls (top row) and 7-MX–treated monkeys (bottom row). All of the animals were reared with +3.0 D lenses in front of their treated eyes and plano lenses in front of their fellow eyes. The thin gray lines in each plot represent data for the right eyes of the 37 normal control monkeys. The panels in each row are arranged from left to right according to the maximum degree of hyperopic anisometropia at the end of the lens-rearing period. The monkeys represented in panels (A, F, E, J) exhibited the smallest and largest degrees of hyperopic anisometropia, respectively. The monkeys in panels (C, H) exhibited the median degree of hyperopic anisometropia in their respective group.

Figure 3.

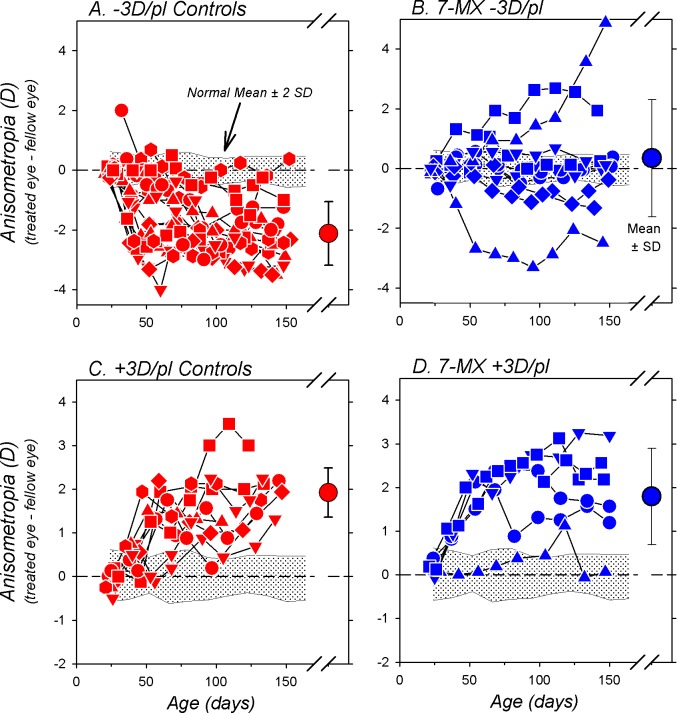

Interocular differences in refractive error (treated eye–fellow eye) plotted as a function of age for individual animals in the −3D/pl controls (A), the 7-MX −3D/pl group (B), the +3D/pl controls (C), and the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys (D). The large symbols on the right in each plot show the mean (±1 SD) anisometropia at the end of the lens-rearing period. The shaded area in each plot represents ±2 SDs of the mean anisometropia for the 37 normal control monkeys.

Administration of 7-MX did not prevent compensating hyperopic shifts in the treated eye's refraction (Fig. 2, bottom row). During the lens-rearing period, all of the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys exhibited absolute hyperopic shifts in their treated eyes (blue symbols). At the end of the lens-rearing period, the treated eyes of these 7-MX monkeys were substantially more hyperopic than the average normal monkey (thin solid lines) and five of six 7-MX +3D/pl animals showed obvious compensating hyperopic anisometropias. The only animal that failed to exhibit a compensating hyperopic anisometropia developed substantial hyperopic errors in both eyes (Fig. 2F).

The effects of 7-MX on compensation for the optically imposed anisometropia are summarized in Figure 3. In comparison to normal monkeys, the lens-reared controls exhibited consistent compensating anisometropic changes in response to either −3 or +3 D of imposed monocular defocus (−3D/pl, F = 33.1, P = 0.0001; +3D/pl, F = 29.7, P = 0.0001). At the end of the lens-rearing period, 16 of 17 −3D/pl control animals manifested myopic anisometropias that were more than 2 SDs below the mean for normal monkeys (Fig. 3A); the average ametropias for the treated eyes were significantly less hyperopic/more myopic than their fellow control eyes (+0.68 ± 1.77 vs. +2.78 ± 1.20 D; P < 0.001). Similarly, all nine of the +3D/pl control animals developed compensating hyperopic anisometropias that were larger than any anisometropias observed in normal monkeys (Fig. 3C); the average treated eye ametropias were significantly more hyperopic than their fellow control eyes (+4.77 ± 0.91 vs. +2.91 ± 1.03 D; P < 0.001).

Administration of 7-MX eliminated the consistent myopic anisometropia normally produced by −3 D of imposed monocular defocus. At the end of the lens-rearing period, only two of 10 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys had myopic anisometropias (Fig. 3B). The average treated and fellow eye ametropias of the 7-MX −3D/pl animals were similar (+4.89 ± 3.04 vs. +4.54 ± 2.11 D; P = 0.59). The temporal pattern of anisometropia for the 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys was significantly different from that for the −3D/pl controls (F = 7.7, P = 0.0003), and at the end of the treatment period the average anisometropia was significantly smaller and more hyperopic than the compensating myopic anisometropia observed in the −3D/pl controls (+0.34 ± 1.96 vs. −2.10 ± 1.01 D, P = 0.003). In contrast, compensation for +3 D of imposed monocular defocus was robust in five of six 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys (Fig. 3D). Although one 7-MX +3D/pl monkey was essentially isometropic at the end of the lens-rearing period, on average the treated eyes of these animals were significantly more hyperopic than their fellow eyes (+6.10 ± 1.71 vs. +4.31 ± 1.97 D; P = 0.01). Over the course of the treatment period, the pattern of anisometropia for the 7-MX +3D/pl animals was not different from that for the +3D/pl controls (F = 0.72, P = 0.55) and the final degrees of anisometropia were comparable (1.79 ± 1.11 D vs. +1.86 ± 0.54 D; P = 0.81).

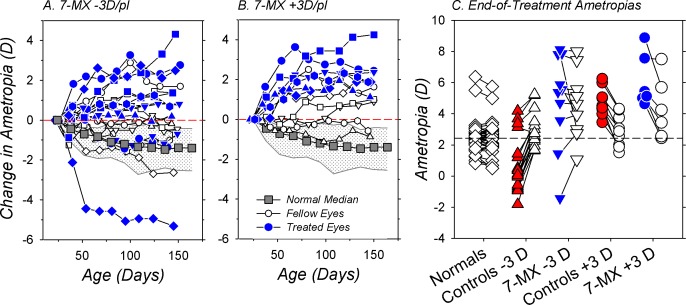

In comparison to normal monkeys, 7-MX changed the course of emmetropization in both the treated and fellow eyes of the lens-reared monkeys (F = 3.3–17.4, P = 0.05–0.0001). This point is emphasized in Figures 4A and 4B, which show the longitudinal changes in refractive error for the treated (blue symbols) and fellow eyes (white symbols) of the 7-MX −3D/pl and 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys, respectively. At ages corresponding to the start of the lens-rearing period, the normal monkeys were typically moderately hyperopic and, as illustrated by their median data (gray squares), exhibited systematic reductions in hyperopia during the course of emmetropization. In comparison, only one 7-MX −3D/pl monkey, the animal that exhibited clear evidence of myopic anisometropic compensation (Fig. 1J), showed larger reductions in hyperopia than the median normal animal. In the 7-MX −3D/pl group, absolute increases in hyperopia were observed in seven treated and five fellow eyes. In the 7-MX +3D/pl animals, all of the treated eyes and four of six fellow eyes showed absolute increases in hyperopia. As a result, the average changes in refractive error that took place over the course of the lens-rearing period for both the treated and fellow eyes of the 7-MX −3D/pl (+0.53 ± 2.65 D and +0.13 ± 1.47 D) and the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys (+2.32 ± 1.06 D and +0.66 ± 1.13 D) were significantly more hyperopic than those found in normal, age-matched monkeys (−1.47 ± 1.70 D; F = 5.1–27.9, P = 0.0001–0.03). Moreover, the average refractive-error changes during the treatment period in the 7-MX monkeys were more hyperopic than those observed in the treated and fellow eyes of the lens-reared controls (−3D controls: treated eyes, −3.23 ± 1.09 D, P = 0.001 and fellow eyes, −1.02 ± 0.65, P = 0.04; +3D controls: treated eyes, +0.30 ± 1.36 D, P = 0.004 and fellow eyes, −1.66 ± 1.45, P = 0.002).

Figure 4.

Relative changes in spherical-equivalent refractive error plotted as a function of age for the treated (blue symbols) and control eyes (white symbols) of individual 7-MX–treated monkeys that were reared with −3 D (A) and +3 D of imposed anisometropia (B). The data were normalized to the refractive errors at the start of the treatment period (the first symbol in each function). The gray squares represent the median changes in refractive error for age-matched normal control animals. The stippled area demarcates the 25% and 75% limits for the normal animals. (C) Ametropias obtained at ages corresponding to the end of the lens-rearing period for individual animals. The right and left eyes of the normal monkeys are represented by open symbols. For the lens-reared animals, the filled and open symbols represent the treated and control eyes, respectively. The short solid lines connect the data for the two eyes of a given animal. The dashed horizontal line represents the right eye median for normal monkeys.

A comparison of the end of treatment ametropias between the 7-MX monkeys and the control and normal monkeys emphasizes how 7-MX altered the course of emmetropization in both the treated and fellow eyes (Fig. 4C). At the end of lens-rearing period, the median refractive errors for both the treated and fellow control eyes of the 7-MX −3D/pl (+5.47 and +4.28 D) and the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys (+5.28 and +3.84 D) were significantly more hyperopic than that for normal age-matched monkeys (+2.47 D; P = 0.0003–0.01). The median end of treatment ametropias for the treated and fellow eyes of the 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys were also more hyperopic than the treated- (+0.38 D, P = 0.002) and fellow-eye medians (+2.75 D, P = 0.05) for the −3D/pl lens-reared controls. Similarly, at the end of the treatment period, there was a trend for the median ametropias of the treated and fellow eyes of the 7-MX +3D/pl to be more hyperopic than those of the +3D/pl controls (treated eyes: +4.50 D, P = 0.08; fellow eyes: +2.88 D, P = 0.22).

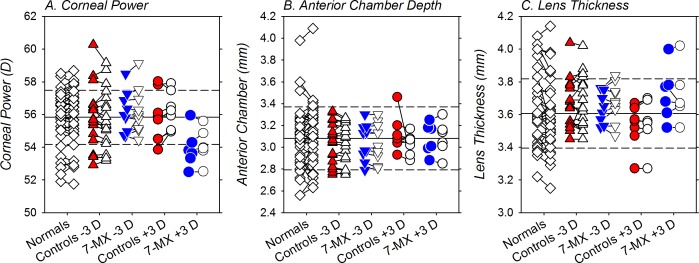

Figure 5 shows the end of treatment corneal powers (Fig. 5A), anterior chamber depths (Fig. 5B), and lens thicknesses (Fig. 5C) for both eyes of individual animals in all five subject groups (see Table 2). Inspection of Figure 5 reveals that neither the lens-rearing procedures nor the administration of 7-MX altered these ocular dimensions. For the lens-reared controls and the 7-MX animals, there were no significant interocular differences in corneal power (T = −1.87 to 0.71, P = 0.10–0.49), anterior chamber depth (T = −0.50 to 1.49, P = 0.18–0.84), or lens thickness (T = −1.66 to 0.42, P = 0.14–0.69). With the exception of the corneal powers of one monkey in the −3 D control group, all of the biometric measures for the lens-reared controls and the 7-MX–treated monkeys fell within 2 SDs of the average values for normal monkeys. Moreover, 1-way ANOVAs demonstrated that at the end of the treatment period there were no between-group differences in absolute corneal power (F = 2.01, P = 0.10), anterior chamber depth (F = 0.20, P = 0.94), or lens thickness (F = 1.19, P = 0.32).

Figure 5.

Corneal power (A), anterior chamber depth (B), and crystalline lens thickness (C) obtained at ages corresponding to the end of the lens-rearing period. The left and right eyes of the normal monkeys are represented by the open diamonds. For the lens-reared monkeys, the treated and fellow control eyes are shown as filled and open symbols, respectively. The solid horizontal line indicates the average for the normal monkeys and the dashed lines represent ±1 SDs from the normal mean.

Table 2.

Average (±SD) End of Treatment Refractive and Biometric Measures

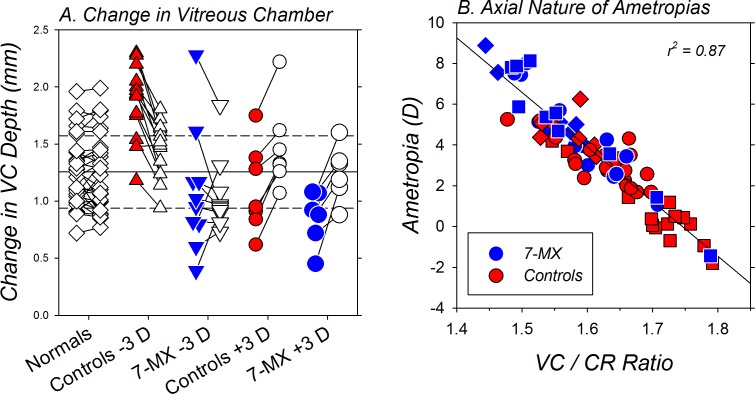

The axial basis of the refractive-error alterations produced by the lens-rearing procedures and the 7-MX treatment is illustrated in Figure 6. Figure 6A shows the changes in vitreous chamber depth that took place in both eyes of individual monkeys. There are two key points to Figure 6A. First, the three subject groups that exhibited significant degrees of anisometropia at the end of the treatment period also exhibited interocular differences in vitreous chamber elongation. In particular, the treated eyes of the −3D/pl controls increased more in vitreous chamber depth than their fellow control eyes (1.82 ± 0.31 vs. 1.43 ± 0.25 mm, T = 3.96, P = 0.001). On the other hand, compared with that in their fellow eyes, vitreous chamber elongation was significantly retarded in the treated eyes of the +3D/pl controls (1.10 ± 0.39 vs. 1.45 ± 0.37 mm, T = −7.79, P < 0.001) and the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys (0.85 ± 0.24 vs. 1.25 ± 0.24 mm, T = −5.25, P = 0.003). The 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys did not develop significant degrees of anisometropia during the lens-rearing period and there were no systematic interocular differences in vitreous chamber elongation between their treated and fellow eyes (1.08 ± 0.54 vs. 1.05 ± 0.32 mm, T = 0.31, P = 0.77).

Figure 6.

(A) Relative changes in vitreous chamber depth measured over ages corresponding to the lens-rearing period for individual normal monkeys (open diamonds) and the treated (filled symbols) and control eyes (open symbols) of the lens-reared controls (red symbols) and the 7-MX monkeys (blue symbols) reared with −3 D or +3 D of imposed anisometropia. The short solid lines connect the data for the two eyes of a given animal. The solid horizontal line indicates the average for the normal monkeys and the dashed lines represent ±1 SD from the mean. (B) End of treatment ametropias plotted as a function of the vitreous chamber/corneal radius ratios for the eyes of individual lens-reared monkeys. The blue and red symbols represent data from the 7-MX– and control lens-reared monkeys, respectively. The squares and diamonds represent data for the treated eyes that viewed through +3 D and −3 D lenses, respectively. The circles represent data for the fellow control eyes.

The second key point illustrated in Figure 6A is that the relative hyperopic refractive errors found in both eyes of the 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys were associated with significantly smaller than normal amounts of vitreous chamber elongation. For example, the fellow eyes of the 7-MX −3D/pl animals showed lower degrees of vitreous chamber elongation in comparison to normal monkeys (1.20 ± 0.32 mm; T = −1.78, P = 0.05) and both the treated (T = −4.26, P = 0.001) and fellow eyes (T = −3.15, P = 0.006) of the 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys exhibited smaller degrees of vitreous chamber elongation than that observed in the −3D/pl controls. Similarly, the increases in vitreous chamber depth in the treated (T = −1.43, P = 0.18) and fellow eyes (T = −1.29, P = 0.23) of the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys were smaller than those in the +3D/pl controls, but these differences were not significant.

The end of treatment ametropias are plotted as a function of the ratio between the vitreous chamber depth and the anterior corneal radius of curvature (VC/CR) for individual eyes of the lens-reared controls and the 7-MX–treated monkeys in Figure 6B. Because there were no between-group differences in corneal power, calculating the ratio between vitreous chamber depth and corneal radius takes into account the effects of inter-subject differences in corneal power on vitreous chamber depth. In this respect, the highly significant correlation between the final absolute refractive errors and the VC/CR ratio (r2 = 0.87, P < 0.0001) demonstrates that the treatment-related, between-subject differences in refractive error were due to the effects of the lens-rearing procedures and the 7-MX treatments on vitreous chamber elongation.

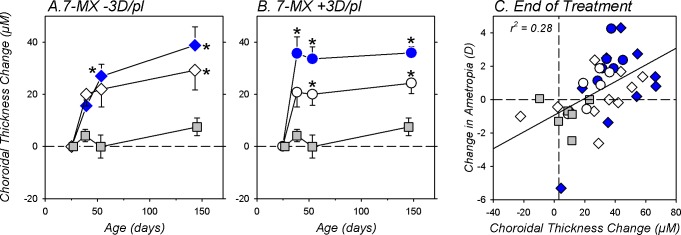

The 7-MX treatment regimen produced substantial increases in choroidal thickness. In Figures 7A and 7B the longitudinal changes in choroidal thickness are plotted for the treated (blue symbols) and fellow eyes (white symbols) of the 7-MX −3D/pl and 7-MX +3D/pl subjects, respectively. For reference the solid gray symbols in each plot show the average choroidal thickness changes in the left eyes of six normal untreated monkeys. Over ages that corresponded to the lens-rearing period, the normal monkeys exhibited, on average, a small increase in choroidal thickness (7.6 ± 3.4 μm). Both the treated and fellow eyes of the 7-MX monkeys exhibited significantly larger increases in choroidal thickness (F = 2.6–9.1, P = 0.05–0.0002). At the end of the lens-rearing period, the increases in choroidal thickness for the 7-MX subjects were between 3.2 to 5.1 times larger than those observed in the normal monkeys. These increases in choroidal thickness in the treated eyes of the 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys are particularly noteworthy because imposed hyperopic defocus has been shown to produce choroidal thinning in control monkeys.83

Figure 7.

The average (±SEM) relative changes in choroidal thickness for the treated (blue symbols) and fellow control eyes (open symbols) of 7-MX–treated monkeys reared with −3 D (A) and +3 D of imposed anisometropia (B). The solid gray symbols represent data from untreated normal eyes. The asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) between the normal and 7-MX monkeys. (C) Changes in ametropia that took place during the lens-rearing period plotted as function of the changes in choroidal thickness for individual animals. The gray squares represent untreated normal eyes. The circles and diamonds symbols represent the 7-MX +3D/pl and 7-MX −3D/pl monkeys, respectively. The treated and fellow eyes of the 7-MX–treated monkeys are represented by the filled and open symbols, respectively. The solid line was determined by linear regression analysis.

At the end of the treatment period there were no interocular differences in choroidal thickness between the treated and fellow eyes of the 7-MX −3D/pl animals (treated eye = 163.5 ± 22.5 μm; fellow eye = 156.6 ± 25.1 μm; T = 1.52, P = 0.16). On the other hand, the choroids in the lens-treated eyes of the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys were significantly thicker than those in their fellow eyes (170.1 ± 26.0 vs. 163.4 ± 25.1; T = 2.69, P = 0.04). In lens-reared control monkeys, changes in choroidal thickness are significantly correlated with the degree of compensating anisometropia (2.7 μm/D).87 At the end of the lens-rearing period, the treated eyes of the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys were on average approximately 2 D more hyperopic than their fellow eyes and the treated-eye choroids were 6.7-μm thicker. In this respect, the magnitude of the interocular differences in choroidal thickness observed in the 7-MX +3D/pl animals suggests that the 7-MX did not substantially alter the choroidal thickness changes produced by myopic defocus. However, it is important to note that although the increases in choroidal thickness were in the appropriate direction to contribute to the hyperopic ametropias in both groups of 7-MX–treated monkeys and the hyperopic anisometropias in the 7-MX +3D/pl monkeys, the largest observed changes in choroidal thickness would account for less than a 0.25 D change in refractive error (i.e., the alterations in axial elongation noted above dominated the observed refractive error changes).

The changes in choroidal thickness, which occurred shortly after the onset of treatment and remained relatively stable throughout the observation period, were positively correlated with the refractive error changes observed in the 7-MX monkeys (Fig. 7C; r2 = 0.28, P = 0.001). While, as stated above, the absolute changes contributed little to the absolute change in refractive error, the choroidal changes preceded the refractive changes and were predictive of the magnitude of the refractive changes.

Discussion

Our main finding was that the oral administration of the nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist, 7-MX, altered vision-dependent emmetropization in infant monkeys in a direction-specific manner. Specifically, the 7-MX regimen produced absolute hyperopic shifts in the refractive errors of both the treated and fellow eyes of the 7-MX monkeys. Moreover, the 7-MX treatments dramatically reduced the compensating axial myopic anisometropias normally produced by imposed monocular hyperopic defocus. However, in contrast, the 7-MX regimen did not prevent, and in fact augmented, the compensating hyperopic refractive errors normally produced by imposed monocular myopic defocus. The alterations in refractive development observed in both eyes of the 7-MX monkeys were axial in nature, being highly correlated with vitreous chamber depth.

Comparisons Between Different Species

The effects of 7-MX on vision-induced ocular growth and refractive development in infant monkeys are in some respects qualitatively similar to those observed previously in guinea pigs,53 rabbits,52 and chickens (Wang K, et al. IOVS 2014;55:ARVO E-Abstract 3040). Specifically, in guinea pigs and rabbits, oral administration of 7-MX reduced the degree of form-deprivation myopia by 46% and 18%, respectively, in comparison to form-deprived controls. Although 7-MX did not alter the course of form-deprivation myopia in chickens, it did reduce the degree of myopic compensation for imposed hyperopic defocus by 23%. These protective effects of 7-MX against vision-induced myopia were, as observed in infant monkeys, associated with reductions in the overall axial elongation of the treated eyes relative to their fellow eyes. However, in the only previous studies that reported the contributions of individual ocular components, the reductions in axial length in lens-reared chickens were primarily the result of a decrease in anterior chamber depth (Wang K, et al. IOVS 2014;55:ARVO E-Abstract 3040). In contrast in monkeys, alterations in vitreous chamber depth were clearly responsible for the overall differences in axial length and refractive error.

In addition to the effects on the treated eyes of infant monkeys, 7-MX also changed the course of emmetropization and the rate of vitreous chamber elongation in the fellow control eyes of the treated monkeys. In particular, the fellow eyes of many of the 7-MX–treated monkeys showed absolute hyperopic shifts over the course of treatment and smaller than normal increases in vitreous chamber depth. In contrast, refractive development in the fellow control eyes of 7-MX–treated rabbits52 and guinea pigs53 was not different from that observed in control or normal animals. It is interesting, however, that relative to normal eyes, the fellow eyes of guinea pigs and rabbits treated with 7-MX showed increases in scleral collagen fiber diameter that were comparable to those in their treated eyes.

Comparisons between studies suggest that the magnitude of the protective effects of 7-MX on vision-induced myopia and possibly on fellow-eye refractive development may be dependent on the dosing regimen. For example, the protective effects against form-deprivation myopia were smaller in the rabbit52 and chicken studies (Wang K, et al. IOVS 2014;55:ARVO E-Abstract 3040), which employed daily or twice daily doses of 30 mg/kg of 7-MX, respectively. The larger effects against form-deprivation myopia observed in guinea pigs53 may reflect the higher dosages of 7-MX that were used in that study (300 mg/kg once a day). Similarly, the more robust effects of 7-MX against negative lens–induced myopia observed in monkeys versus chickens may have occurred because our monkeys were treated with 100 mg/kg twice each day, over 3 times higher than the dosage used in chickens (30 mg/kg twice a day).

How Does 7-MX Alter Refractive Development?

In the fibrous layers of the sclera, particularly in the mammalian eyes that do not have a cartilaginous layer (e.g., primate eyes), myopic axial elongation is associated with scleral remodeling that includes a reduction in collagen content, a decrease in collagen fibril diameter, and a decrease in overall thickness of the posterior sclera.47,48,88–90 These changes alter the mechanical properties of the sclera making it more extensible and more susceptible to myopic axial elongation.50 The initial interest in adenosine receptor antagonists as potential therapeutic agents to slow myopia progression emerged from the observation that oral administration of either theobromine or 7-MX, both metabolites of caffeine, increased the collagen-related amino acid content, the collagen fibril diameter, and the thickness of the posterior sclera in rabbits49,52 and guinea pigs.53 It was hypothesized that the changes produced by 7-MX would improve the biomechanical properties of the sclera reducing the potential for myopic axial elongation.53 The observation that all known subtypes of adenosine receptors are found in human scleral fibroblasts supported the idea that adenosine antagonists could directly influence scleral remodeling.91

The increases in choroidal thickness observed in the 7-MX–treated monkeys do not necessarily rule out the possibility that the primary site of action of 7-MX is the sclera. However, given that the choroid is a critical component in the vision-dependent cascade that mediates normal refractive development, it is possible that 7-MX affects refractive development by influencing or altering the operational properties of this emmetropization cascade. A large body of evidence supports the hypothesis that vision-dependent emmetropization is regulated by local retinal mechanisms, which generate biochemical signals that reflect the eye's effective refractive state. The signal cascade passes from the inner retina, through the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choroid, and eventually modulates the biochemical and mechanical nature of the sclera in a manner that promotes changes in overall axial length that normally eliminate refractive errors.92 The effects of 7-MX on refractive development could have come about by influencing this visually driven signal cascade at a number of different locations. All four subtypes of adenosine receptors have been identified in the neural retina, pigment epithelium, choroid, and sclera.93,94 At least some of these receptors appear to be involved in emmetropization and the regulation of axial elongation. For instance, the pattern of adenosine receptor expression in different ocular tissues is altered by form deprivation in guinea pigs93 and genetic deletion of the A2A adenosine receptor in mice promotes axial myopia.95 Although it is possible our 7-MX treatments indirectly influenced the emmetropization process via nonadenosine receptors (e.g., via off-target actions on purinergic receptors),96 the known effects of adenosine mechanisms in nonocular tissue suggest that receptor antagonists, such as 7-MX, could influence the retinal components of the signal cascade in a number of ways (e.g., by modulating dopamine or acetylcholine transmission97–101 or altering ocular circadian rhythms97,102) However, given that metabolites of caffeine such as 7-MX do not readily penetrate the blood–brain barrier103 (nor probably the blood–retina barrier), it may be more likely that 7-MX influences mechanisms in the RPE, choroid, and/or sclera directly.

The role of the RPE in the signal cascade is multifactorial. The RPE regulates ion and fluid exchange between the choroid and neural retina. Consequently, alterations in RPE ion and fluid transport could modulate choroidal thickness in ways that could have both direct and indirect effects on the eye's refractive status.104–109 In addition, the RPE is a source for a number of growth factors that are potentially involved in the regulation of eye growth.108 In this respect, 7-MX could influence these RPE functions directly via adenosine receptors in the RPE. Even though the ability of 7-MX to cross the blood–retina barrier is weak, it may still influence mechanisms in the RPE by way of the basal (choroidal) membrane. Another methylated xanthine, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), likewise does not penetrate the blood–brain barrier nor the blood–retina barrier to any great extent.110 Nevertheless, perfusion of the basal surface of a RPE-choroid preparation from chickens with IBMX produces RPE-dependent electrophysiological responses.111 Thus, it is feasible that even if 7-MX did not effectively cross the blood–retina barrier, it could directly or indirectly influence RPE components involved in the emmetropization cascade.

The choroid is also a key component in the emmetropization signal cascade. For example, the production of choroidal all-trans-retinoic acid, a putative signal molecule in this cascade, and the thickness of the choroid are modulated in a bidirectional manner by visual signals that increase and decrease axial elongation rates.112 These changes in choroidal thickness, which are in the appropriate direction to correct for the existing refractive errors, precede and accompany the development of vision-induced ametropias in animals.83,113,114 Choroidal thickness, which is also affected by pharmaceutical agents that influence axial growth,115–117 is a reliable, although not necessarily perfect,118 indicator of the direction of vision-dependent growth (i.e., encoded sign of defocus).119–122 The observed changes in choroidal thickness could be a direct effect of 7-MX on adenosine receptors in the choroid or a downstream effect of the actions of 7-MX on the RPE. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that 7-MX causes thickening of the choroid via some direct, unrelated mechanism. Therefore, it is possible that the observed thickening of the choroid may be an unwanted side effect of the 7-MX treatments.

The ocular component changes responsible for the relative hyperopic refractive errors observed in the fellow control eyes of the 7-MX–treated monkeys are in agreement with the idea that 7-MX modulated or altered the operational properties of the cascade that normally mediates emmetropization. In particular, the underlying ocular changes (specifically, reduced vitreous chamber elongation rate in the absence of treatment-induced changes in corneal power, anterior chamber depth, and crystalline lens thickness) are identical to those responsible for the hyperopic shifts produced by myopic defocus in lens-reared control animals. Specifically, in both cases, the hyperopia came about because the rate of axial elongation was reduced while the eye's overall refractive power decreased as a consequence of the normal flattening processes in the cornea and crystalline lens.

Regardless of the site or mechanism of action of 7-MX, the observed reductions in vitreous chamber elongation rate and the resulting effects on refractive development were consistent, sustained for the duration of treatment, and robust, and occurred even in the presence of hyperopic defocus, a visual signal that normally increases axial elongation producing myopia.65,68

Clinical Implications

Our results demonstrate that adenosine receptor antagonists have potential in treatment regimens for preventing or slowing the progression of myopia in children and provide support for the recent clinical trials investigating the efficacy of 7-MX in retarding myopia progression. As a therapeutic agent for treating myopia, 7-MX has a number of positive attributes. Most importantly, 7-MX, which is a common dietary ingredient, has a good safety record in the limited clinical trials conducted to date, with no significant adverse effects noted over treatment periods that were 3 years in duration for some children (Trier K, et al. IOVS 2017;58:ARVO E-Abstract 2385).51 In this respect, we did not observe any adverse side effects in the 7-MX–treated monkeys.

The results for this study suggest that 7-MX could be beneficial in slowing myopia progression in two ways. First, 7-MX retarded the ability of hyperopic defocus, the presumed stimulus for myopia progression in children,123 to produce myopia. Second, 7-MX did not interfere with the reduction in axial elongation produced by imposed myopic defocus, and in fact may have exaggerated these optical effects. It has been suggested that defocus signals produce separate “stop” and “go” signals that modulate axial elongation.124 If this is correct, 7-MX appears to reduce “go” signals and to possibly amplify “stop” signals. Regardless, this second point has practical significance, because it supports the idea that combining optical treatment strategies that impose relative myopic defocus over all or a large part of the visual field with 7-MX would have a greater effect than either 7-MX or the optical treatment strategies alone. Although our results are encouraging, it is important to recognize that the site and mechanism of action of 7-MX are still unknown.

Are the hyperopic shifts, particularly those observed in the fellow control eyes of the 7-MX–treated monkeys, a contraindication for using adenosine antagonists to slow myopia progression in children? For example, would 7-MX produce unwanted hyperopia in treated myopic children? This possibility is unlikely primarily because of the ocular basis for the hyperopic shifts produced by 7-MX. As described above, the hyperopia came about because 7-MX selectively slowed vitreous chamber elongation without altering the normal reduction in the eye's refracting power that occurred as the cornea and crystalline lens followed their normal growth patterns. In this respect, current treatment regimens for myopia progression, which all slow vitreous chamber elongation without altering the refracting power of the eye, have the potential to produce hyperopic shifts in infant eyes, specifically in eyes in which the cornea and crystalline lens have not reached optical maturity. As shown in Figure 2, optical treatment strategies that imposed myopic defocus can produce hyperopia in infant primates. Similarly,125 chronic topical atropinization can produce axial hyperopia in infant monkeys125 and infant mice.126

It is important to note that the potential for treatment strategies that slow axial elongation to produce hyperopia decreases dramatically with the subject's age. Once, the cornea and crystalline lens are optically mature, 7-MX, atropine, and the currently employed optical treatment strategies would not be expected to produce hyperopic shifts. In humans, the cornea assumes adult refracting powers as early as 18 to 24 months of age.127 The greatest changes in lens power occur before 5 years of age with only small, slow changes in lens power occurring after the typical onset ages for juvenile-onset myopia (8–10 years in the United States).127 As a consequence, at ages when these antimyopia treatment strategies would be employed, it is highly unlikely that hyperopia would be produced.

With respect to extrapolating our results to clinical treatment strategies, it is also important to note that the dosage of 7-MX that we employed in monkeys was substantially higher than those used in the previous clinical trials involving children. Whereas our animals received 100 mg/kg of 7-MX twice daily, children were prescribed either 400 mg of 7-MX once or twice a day (i.e., 800 mg total). Based on the average weights of 8- (26 kg) and 13-year-old Danish females (45 kg),128 the per kilogram dosages of 7-MX used in the previous clinical trials varied from a low of 8.9 to a high of 30.8 mg/kg per day, which were for some children more than 22 times lower than the total per kilogram daily dosages employed in this study. From an efficacy perspective, it will be important to evaluate the effects of the 7-MX dose levels on the antimyopia effects observed in this study. Moreover, although we did not observe any overt behavioral, ocular, or systemic adverse effects related to the 7-MX treatments, the dosages that we employed were higher than those used in any previous animal or human study and we cannot, at this time, rule out subtle toxic effects in either the retina or other ocular structures. Thus, from a safety perspective a thorough examination of the function and structure of the retina, pigment epithelium, choroid, and sclera in 7-MX–treated animals is essential. Nevertheless, the results from this study support further investigations into the efficacy of 7-MX in therapeutic regimens to reduce myopia progression.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY-03611 and EY-07551 (Bethesda, MD, USA) and funds from the Brien Holden Vision Institute (Sydney, Australia) and the University of Houston Foundation (Houston, TX, USA).

Disclosure: L.-F. Hung, None; B. Arumugam, None; L. Ostrin, None; N. Patel, None; K. Trier, Theialife (I), P; M. Jong, None; E.L. Smith III, None

References

- 1. Holden BA,, Sankaridurg P,, Smith EL, III,, Aller TA,, Jong M,, He M. Myopia, an underrated global challenge to vision: where the current data takes us on myopia control. Eye (Lond). 2014; 28: 142–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lin LL,, Shih YF,, Hsiao CK,, Chen CJ. Prevalence of myopia in Taiwanese schoolchildren: 1983–2000. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004; 33: 27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Woo WW, Lim DA, Yang H, et al. et al . Refractive errors in medical students in Singapore. Singapore Med J . 2004; 45: 470–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu MM,, Edwards MH. The effect of having myopic parents: an analysis of myopia in three generations. Optom Vis Sci. 1999; 76: 387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tay MT,, Au Enog KG,, Ng CY,, Lim MK. Myopia and educational attainment in 421,116 young Singaporean males. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1992; 21: 785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang TJ,, Chiang TH,, Wang TH,, Lin LLK,, Shih YF. Changes of the ocular refraction among freshmen in national Taiwan University between 1988 and 2005. Eye (Lond). 2008; 23: 1168–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jung SK,, Lee JH,, Kakizaki H,, Jee D. Prevalence of myopia and its association with body stature and edcuational level in 19-year-old male concscripts in Seoul, South Korea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 5579–5583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vitale S,, Ellwein L,, Cotch MF,, Ferris FL,, Sperduto RD. Prevalence of refractive error in the United States, 1999–2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008; 126: 1111–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sperduto RD,, Seigel D,, Roberts J,, Rowland M. Prevalence of myopia in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983; 101: 405–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katz J,, Tielsch JM,, Sommer A. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in an adult inner city population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997; 38: 334–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Q,, Klein BE,, Kleini R,, Moss SE. Refractive status in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994; 35: 4344–4347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Framingham Offspring Eye Study Group. Familial aggregation and prevalence of myopia in the Framingham Offspring Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996; 114: 326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rose K,, Smith W,, Morgan I,, Mitchel P. The increasing prevalence of myopia: implications for Australia. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001; 29: 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bar Dayan Y, Levin A, Morad Y, et al. et al . The changing prevalence of myopia in young adults: a 13-year series of population-based prevalence surveys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 2760–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Williams KM, Bertelsen G, Cumberland P, et al. et al . Increasing prevalence of myopia in Europe and the impact of education. Ophthalmology. 2015; 122: 1489–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vitale S,, Sperduto RD,, Ferris FL. Increased prevalence of myopa in the United States between 1971–1972 and 1999–2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009; 127: 1632–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cotter SA, Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Azen SP, Klein R; for the Los Angeles Eye Study Group. . Causes of low vision and blindness in adult Latinos: the Los Angeles Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113: 1574–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fong DS,, Epstein DL,, Allingham RR. Glaucoma and myopia: are they related? Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1990; 30: 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Flitcroft DI. The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012; 622–660. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. Lim R,, Mitchell P,, Cumming RG. Refractive associations with cataract: the Blue Montain Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999; 40: 3021–3026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leske MC, Wu SY, Nemesure B, Hennis A; for the Barbados Eye Study Group. . Risk factors of incident nuclear opacities. Ophthalmology. 2002; 109: 1303–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wong TY,, Klein BE,, Klein R,, Tomany SC,, Lee KE. Refractive errors and incident cataracts: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 1449–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mitchel P,, Hourihan R,, Sandbach J,, Wang JJ. The relationship between glaucoma and myopia: the Blue Mountain Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106: 2010–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wong TY,, Klein BE,, Klein R,, Knudtson M,, Lee KE. Refractive errors, intraocular pressure and glaucoma in a white population. Ophthalmology. 2003; 110: 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Curtin BJ,, Karlin DB. Axial length measurements and fundus changes of the myopic eye. I. The posterior fundus. Trans Am Ophthalmolg Soc. 1970; 68: 312–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Risk factors for idiopahtic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. The Eye Disease Case-Control Study group. Am J Epidemiol. 1993; 137: 749–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saw SM,, Gazzard G,, Shih-Yen EC,, Chua W-H. Myopia and associated pathological complications. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 2005; 25: 381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iwase A, Araie M, Tomidokoro A; for the Tajimi Study Group. . Prevalence and causes of low vision and blindness in a Japanese adult population: The Tajimi study. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113: 1354–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsu WM,, Cheng JH,, Liu JH,, Tsai SY,, Chou P. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in an elderly Chineses population in Taiwan: the Shihpai Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111: 62–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong TY,, Ferreira A,, Hughes R,, Carter G,, Mitchel P. Epidemiology and disease burden of pathologic myopia and myopic choroidal neovascularization: an evidence-based systematic review. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014; 157: 9–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vitale S,, Cotch MF,, Sperduto RD,, Ellwein L. Costs of refractive correction of distance vision impairment in the United States, 1999–2002. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113: 2163–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rein DB, Zhang P, Wirth KE, et al. et al . The economic burden of major adult visual disorders in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006; 124: 1754–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frick KD. What the comprehensive economics of blindness and visual impairment can help us understand. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2012; 60: 406–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vitale S,, Cotch MF,, Sperduto RD. Prevalence of visual impairment in the United States. JAMA. 2006; 295: 2158–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kemper AR,, Wallace DK,, Zhang X,, Patel N,, Crews JE. Uncorrected distance visual impairment amoung adolescents in the United States. J Adol Health. 2012; 50: 645–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Si JK,, Tang K,, Bi H-S,, Guo D-D,, Guo J-J,, Wang X-R. Orthokeratology for myopia control: a meta-analysis. Optom Vis Sci. 2015; 92: 252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Walline JJ. Myopia control: a review. Eye Contact Lens. 2016; 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith EL., III Optical treatment strategies to slow myopia progression: effects of the visual extent of the optical treatment zone. Exp Eye Res. 2013; 114: 77–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chia A, Chua W-H, Cheung Y-B, et al. et al . Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia: safety and efficacy of 0.5%, 0.1%, and 0.01% doses (atropine for the treatment of myopia 2). Ophthalmology. 2012; 119: 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chia A,, Lu Q-S,, Tan D. Five-year clinical trial on atropine for the treatment of myopia 2: myopia control with atropine 0.01% eyedrops. Ophthalmology. 2016; 56: 391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shih YF,, Hsiao CK,, Chen CJ,, Chang CW,, Hung PT,, Lin LL. An intervention trial on efficacy of atropine and multi-focal glasses in controlling myopic progression. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2001; 79: 233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cooper J,, Eisenberg N,, Shulman E,, Wang FM. Maximum atropine dose without clinical signs or sympotms. Optom Vis Sci. 2013; 90: 1467–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chia A,, Chua W-H,, Wen L,, Fong A,, Goon YY,, Tan D. Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia: changes after stopping atropine 0.01%, 0.1% and 0.5%. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014; 157: 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Loughman J,, Flitcroft DI. The acceptability and visual impact of 0.01% atropine in a Caucasian population. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017; 100: 1525–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smith EL, III,, Redburn DA,, Harwerth RS,, Maguire GW. Permanent alterations in muscarinic receptors and pupil size produced by chronic atropinization in kittens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984; 25: 239–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huang J, Wen D, Wang Q, et al. et al . Efficacy comparison of 16 interventions for myopia control in children: a network meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2016; 123: 697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McBrien NA,, Gentile A. Role of the sclera in the development and pathological complications of myopia. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003; 22: 307–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McBrien NA,, Lawlor P,, Gentile A. Scleral remodeling during the development of and recovery from axial myopia in the tree shrew. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41: 3713–3719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Trier K,, Olsen EB,, Kobayashi T,, Ribel-Madsen SM. Biochemical and ultrastructural changes in rabbit sclera after treatment with 7-methylxanthine, theobromine, acetazolamide, or L-ornithine. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999; 83: 1370–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Siegwart JT,, Norton TT. Regulation of the mechanical properties of tree shrew sclera by the visual environment. Vision Res. 1999; 39: 387–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Trier K,, Ribel-Madsen SM,, Cui D,, Christensen SB. Systemic 7-methylxanthine in retarding axial eye growth and myopia progression: a 36-month pilot study. J Ocul Biol Dis Inform. 2008; 1: 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nie H-H, Huo L-J, Yang X, et al. et al . Effects of 7-methylxanthine on form-deprivation myopia in pigmented rabbits. Int J Ophthalmol. 2012; 5: 133–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cui D, Trier K, Zeng J, et al. et al . Effects of 7-methylxanthine on sclera in form deprivation myopia in guinea pigs. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011; 89: 328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tarka SMJ. The toxicology of cocoa and methylxanthines: a review of the literature. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1982; 9: 275–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tarka SMJ,, Morrissey RP,, Apgar JL. Chronic toxicity/carcinogenecity studies of hte cocoa powder in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 1991; 29: 7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. International Agency for Research on Cancer Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Coffee, tea, mate, methylxanthines and methylglyoxal. Geneva: WHO; 1991; 51: 357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Franco R,, Onatibia-Astilia A,, Martinex-Pinilla E. Health benefits of methylxanthines in cacao and chocolate. Nutrients. 2013; 5: 4159–4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rodopoulos N,, Hojvall L,, Norman A. Elimination of theobromine metabolites in healthy adults. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1996; 56: 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bradley DV,, Fernandes A,, Lynn M,, Tigges M,, Boothe RG. Emmetropization in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta): birth to young adulthood. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999; 40: 214–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kiely PM,, Crewther SG,, Nathan J,, Brennan NA,, Efron N,, Madigan M. A comparison of ocular development of the cynomolgus monkey and man. Clin Vis Sci. 1987; 1: 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Qiao-Grider Y,, Hung L-F,, Kee C-s,, Ramamirtham R,, Smith E., III. Normal ocular development in young rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). Vision Res. 2007; 47: 1424–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fernandes A,, Bradley DV,, Tigges M,, Tigges J,, Herndon JG. Ocular measurements throughout the adult life span of rhesus monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 2373–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Qiao-Grider Y,, Hung L-F,, Kee C-s,, Ramamirtham R,, Smith EL., III. Nature of the refractive errors in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) with experimentally induced ametropias. Vision Res. 2010; 50: 1867–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tigges M,, Tigges J,, Fernandes A,, Eggers HM,, Gammon JA. Postnatal axial eye elongation in normal and visually deprived rhesus monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990; 31: 1035–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Smith EL, III,, Hung L-F. The role of optical defocus in regulating refractive development in infant monkeys. Vision Res. 1999; 39: 1415–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rabin J,, Van Sluyters RC,, Malach R. Emmetropization: a vision-dependent phenomenon. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981; 20: 561–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Phillips JR. Monovision slows juvenile myopia progression unilaterally. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005; 89: 1196–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hung L-F,, Crawford MLJ,, Smith EL., III. Spectacle lenses alter eye growth and the refractive status of young monkeys. Nat Med. 1995; 1: 761–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Smith EL III, Huang J, Hung L-F, et al. et al . Hemiretinal form deprivation: evidence for local control of eye growth and refractive development in infant monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 5057–5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Smith EL, III,, Hung L-F,, Huang J. Relative peripheral hyperopic defocus alters central refractive development in monkeys. Vision Res. 2009; 49: 2386–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Smith EL, III,, Hung L-F,, Huang J,, Blasdel T,, Humbird T,, Bockhorst K. Effects of optical defocus on refractive development in monkeys: evidence for local, regionally selective mechanisms. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 3864–3873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Smith EL, III,, Kee C-s,, Ramamirtham R,, Qiao-Grider Y,, Hung L-F. Peripheral vision can influence eye growth and refractive development in infant monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 3965–3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Smith EL, III,, Hung L-F,, Arumugam B,, Huang J. Negative lens-induced myopia in infant monkeys: effects of high ambient lighting. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 2959–2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Smith EL, III,, Hung L-F,, Kee C-s,, Qiao-Grider Y,, Ramamirtham R. Continuous ambient lighting and lens compensation in infant monkeys. Optom Vis Sci. 2003; 80: 374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hung L-F,, Ramamirtham R,, Huang J,, Qiao-Grider Y,, Smith EL., III. Peripheral refraction in normal infant rhesus monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 3747–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Smith EL, III,, Hung L-F,, Huang J. Protective effects of high ambient lighting on the development of form-deprivation myopia in rhesus monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 421–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Smith EL, III,, Hung L-F,, Arumugam B,, Holden BA,, Neitz M,, Neitz J. Effects of long-wavelength lighting on refractive development in infant rhesus monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 6490–6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Harris WF. Algebra of sphero-cylinders and refractive errors, and their means, variance, and standard deviation. Am J Optom Physiol Optics. 1988; 65: 794–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kee C-s,, Hung L-F,, Qiao-Grider Y,, Roorda A,, Smith EL., III. Effects of optically imposed astigmatism on emmetropization in infant monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004; 45: 1647–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kee C-s,, Hung L-F,, Qiao Y,, Habib A,, Smith EL., III. Prevalence of astigmatism in infant monkeys. Vision Res. 2002; 42: 1349–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rahman W,, Chen FK,, Yeob J,, Patel P,, Tufail A,, Da Cruz L. Repeatability of manual subfoveal choroidal thickness measurements in healthy subjects using the technique of enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 2267–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Chen TC, Cense B, Pierce MC, et al. et al . Spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Ultra-high speed, ultra-high resolution ophthalmic imaging. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005; 123: 1715–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hung L-F,, Wallman J,, Smith EL., III. Vision dependent changes in the choroidal thickness of macaque monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41: 1259–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Pavlin CJ,, Harasiewicz K,, Sherar MD,, Foster FS. Clinical use of ultrasound biomicroscopy. Ophthalmology. 1991; 98: 287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Chakraborty R,, Read SA,, Collins MJ. Diurnal variations in axial length, choroidal thickness, intraocular pressure and ocular biometrics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 54: 353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Spaide RF,, Koizumi H,, Pozonni MC. Enhanced depth imaging spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008; 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hung L-F,, Wallman J,, Smith EL., III. Optical defocus produces changes in the choroidal thickness of macaque monkeys. : Shih FYF,, Hung P, Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on Myopia. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Rada JA,, Nickla DL,, Troilo D. Decreased proteoglycan synthesis associated with form deprivation myopia in mature primate eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41: 2050–2058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. McBrien NA,, Cornell LM,, Gentle A. Structural and ultrastructural changes to the sclera in a mammalian model of high myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 2179–2187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Funata M,, Tokoro T. Scleral change in experimentally myopic monkeys. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1990; 228: 174–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Cui D, Trier K, Chen X, et al. et al . Distribution of adenosine receptors in human sclera fibroblasts. Mol Vis. 2008; 14: 523–529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Wallman J,, Winawer J. Homeostasis of eye growth and the question of myopia. Neuron. 2004; 43: 447–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Cui D,, Trier K,, Zeng J,, Wu K,, Yu M,, Ge J. Adenosine receptor protein changes in guinea pigs with form deprivation myopia. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010; 88: 759–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Brass KM,, Zarbin MA,, Snyder SH. Endogenous adenosine and adenosine receptors localized to ganglion cells of the retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987; 84: 3906–3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhou X, Huang Q, An J, et al. et al . Genetic deletion of the Adensoine A2A receptor confers postnatal developmet of relative myopia in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010; 51: 4362–4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Sanderson J, Dartt DA, Trinkaus-Randall V, et al. et al . Purines in the eye: recent evidence for the physiological and pathological roles of purines in the RPE, retinal neurons, astrocytes, Müeller cells, lens, trabecular mechwork, cornea and lacrimal gland. Exp Eye Res. 2014; 127: 207–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sohni P,, Hartwick ATE. Adenosine modulates light response of rat retinal ganglion cell photoreceptors through a cAMP-mediated pathway. J Physiol. 2014; 592: 4201–4220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Cunha RA. Adenosine as a neuromodulator and as a homeostatic regulator in the nervous system: different roles, different sources and different receptors. Neurochem Int. 2001; 38: 107–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Moo-Puc RE,, Gongora-Alfaro JL,, Alvarez-Cervera FJ,, Pineda JC,, Arankowshy-Sandoval G,, Heredia-Lopez F. Caffeine and muscarinic antagonists act in synergy to inhibit haloperidol-induced catalepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2003; 45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Oliveira L,, Correia-de-SA P. Protein kinase A and Ca(v)I (L-type) channels are common targets to facilitatory adenosine A2A and muscarinic M1 receptors on rat motoneurons. Neurosignals. 2005; 14: 262–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Salmi P,, Chergui K,, Fredholm BB. Adenosine-dopamine interactions revealed in knockout mice. J Mol Neurosci. 2005; 26: 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Stone RA,, Pardue MT,, Iuvone PM,, Khurana TS. Pharmacology of myopia and potential role for intrinsic retinal circadian rhythms. Exp Eye Res. 2013; 114: 35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Shi D,, Daly JW. Chronic effects of xanthines on levels of central receptors in mice. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1999; 19: 719–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]