Abstract

There are a number of changes underway in modern clinical bacteriology laboratories. Panel-based molecular diagnostics are now available for numerous applications, including, but not limited to, detection of bacteria and select antibacterial resistance markers in positive blood culture bottles, detection of acute gastroenteritis pathogens in stool, and detection of selected causes of acute meningitis and encephalitis in cerebrospinal fluid. Today, rapid point-of-care nucleic acid amplification tests are bringing the accuracy of sophisticated molecular diagnostics closer to patients. A proteomic technology, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), is enabling rapid, accurate, and cost-effective identification of bacteria, as well as fungi, recovered in cultures. Laboratory automation, common in chemistry laboratories, is now available for clinical bacteriology laboratories. Finally, there are several technologies under development, such as rapid phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing, whole genome sequencing, and metagenomic analysis for detection of bacteria in clinical specimens. It is helpful for clinicians to be aware of the pace of new development in their bacteriology laboratory to enable appropriate test ordering, test interpretation, and to work with their laboratorians and antimicrobial stewardship programs to ensure that new technology is implemented to optimally improve patient care.

INTRODUCTION

During the past several years, a number of transformations have taken place in clinical bacteriology laboratories, as they move away from traditional methods in place for over a century, towards a new generation of tests. These changes, often made “behind-the-scenes,” without the cognizance of clinicians, have the potential to improve patient care. Clinicians should be mindful of innovations in their laboratory, including the sensitivity, specificity, and advantages and disadvantages of the tests offered, to inform appropriate test utilization and interpretation. With the pace of development of new technology, there is a potential gap between the laboratory and the end user of microbiology information. To address this issue, I will describe recent advances implemented in clinical bacteriology laboratories, and highlight others that may be realized in the near future.

Advances in Traditional Molecular Diagnostics

Nucleic acid amplification tests, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), have become part of daily clinical practice. They allow rapid and sensitive detection of microorganisms, including bacteria, as well as viruses, parasites, and fungi, directly from clinical specimens. Until recently, they have been the domain of large, sophisticated laboratories, and have typically been ordered and performed one-by-one. An advantage of bacterial culture is that it enables growth of many different organism-types in a single test. Today, molecular tests are increasingly being offered as automated, easy to use, rapid panels assembled based on clinically significant organisms likely to be present in the specimen being tested. In some cases, antibacterial resistance genes are detected simultaneously. These new Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved diagnostics have been packaged into pouches, cartridges, etc., that may be inoculated with clinical specimens after minimal processing, and which are automatically run on specifically-designed instruments, putting them within technical reach of laboratories of all sizes and enabling 24/7 availability. Some provide results in as little as an hour. Examples of panel-based molecular diagnostics include those designed for testing positive blood culture bottles, and those designed for testing stool, respiratory specimens and cerebrospinal fluid for acute gastrointestinal, respiratory, and central nervous system pathogens, respectively. One limitation is that molecular panels, despite their breadth, only test for the specific organisms targeted. A strategy to overcome this limitation is to use a broad-range bacterial (e.g., 16S ribosomal RNA gene) nucleic acid amplification strategy such as PCR, along with sequencing of the amplified product to test normally sterile fluids and tissues.1 However, broad-range bacterial PCR/sequencing is not always as sensitive as organism-specific PCR,2,3 and is prone to non-specificity due to the presence of “stray” bacterial DNA associated with specimens, containers, plastics, and/or reagents.

Two companies’ broad molecular panels are approved by the FDA for testing positive blood culture bottles (Table 1), the FilmArray® Blood Culture Identification (BCID) Panel (Biofire Diagnostics, LLC) and the Verigene® Gram-Positive Blood Culture Test (BC-GP) and Gram-Negative Blood Culture Test (BC-GN) (Nanosphere, Inc.). Today, instead of receiving a Gram stain morphology report when a blood culture bottle signals positive, and waiting a day or more for identification of the organism(s) involved, these assays provide microbial identification and detect select antibacterial resistance genes in a one to two-and-a-half hour time frame. While they are accurate, and revolutionary in terms of the speed at which they identify bacteria and yeasts in positive blood culture bottles and, to some extent, characterize resistance of the associated bacteria, they have limitations. They do not always detect all bacteria and yeasts in mixed infections, even when pathogens are a part of the panel. Also, they do not assign resistance genes to individual species in mixed infections. For example, if mecA is detected in the context of mixed infection with Staphylococcus aureus and another species of Staphylococcus, it is impossible to determine which organism is methicillin-resistant (or whether both are methicillin-resistant). These assays do not detect organisms in all patients with positive blood cultures. In my laboratory’s experience, approximately four fifths of patients with positive blood cultures will have positive results with the FilmArray® BCID Panel.4 Detection rates may be higher in locations where typical organisms are expected (e.g., medical/surgical wards, intensive care units) compared to those where more unusual organisms may be more frequent (e.g., cancer or transplant centers). These assays are expensive and because of the workflow involved, are not typically orderable by clinicians. Laboratories, if they choose to utilize these tests, must decide when to deploy them. In order for results to impact patient care, results must be immediately delivered to healthcare practitioners, who in turn are knowledgeable of the status of the patient involved, and more importantly, prepared to rapidly adjust treatment regimens based on results. Test results will be forthcoming from the laboratory at any time the laboratory is staffed (24/7 in our case). Our laboratory group performed a randomized clinical trial evaluating rapid panel-based molecular testing of positive blood culture bottles, in which we showed that despite the rapid availability of sophisticated data, there was no impact on mortality, length of stay, or time to blood culture clearance.4 Notably, benefits were realized in terms of a rapid escalation and de-escalation of antimicrobial agents, particularly in the context of simultaneously deployed antimicrobial stewardship guidance. This is especially important in light of President Obama’s, “National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria.”5 Tests designed for use on positive blood culture bottles are “add-on” tests, performed in addition to standard subcultures of positive blood culture bottles and conventional susceptibility testing of isolated bacteria. As new tests are implemented, systems-based practice changes outside of the laboratory, including intricate involvement of antimicrobial stewardship teams, may need to be implemented to optimize benefits to patients.

Table 1.

Targets of large panels for testing positive blood culture bottles

| Gram Positive Bacteria | Gram Negative Bacteria | Candida species |

|---|---|---|

| FilmArray® Blood Culture Identification (BCID) Panel (BioFire Diagnostics, LLC) | ||

|

Staphylococcus species Staphylococcus aureus Streptococcus species Streptococcus agalactiae Streptococcus pyogenes Streptococcus pneumoniae Enterococcus species Listeria monocytogenes |

Klebsiella oxytoca Klebsiella pneumoniae Serratia species Proteus species Acinetobacter baumannii Haemophilus influenzae Neisseria meningitidis Pseudomonas aeruginosa Enterobacteriaceae Escherichia coli Enterobacter cloacae complex |

Candida albicans Candida glabrata Candida krusei Candida parapsilosis Candida tropicalis |

|

Resistance Genes mecA vanA/vanB |

Resistance Genes blaKPC |

|

| Verigene ® (Nanosphere, Inc.) | ||

|

Gram-Positive Blood Culture Test (BC-GP) |

Gram-Negative Blood Culture Test (BC-GN) |

|

|

Staphylococcus aureus Staphylococcus epidermidis Staphylococcus lugdunensis Streptococcus anginosus group Streptococcus agalactiae Streptococcus pneumoniae Streptococcus pyogenes Enterococcus faecalis Staphylococcus species Streptococcus species Listeria species |

Escherichia coli Klebsiella pneumoniae Klebsiella oxytoca Pseudomonas aeruginosa Acinetobacter species Citrobacter species Enterobacter species Proteus species |

|

|

Resistance Genes mecA vanA vanB |

Resistance Genes blaNDM blaKPC blaOXZ blaVIM blaCTX-M |

|

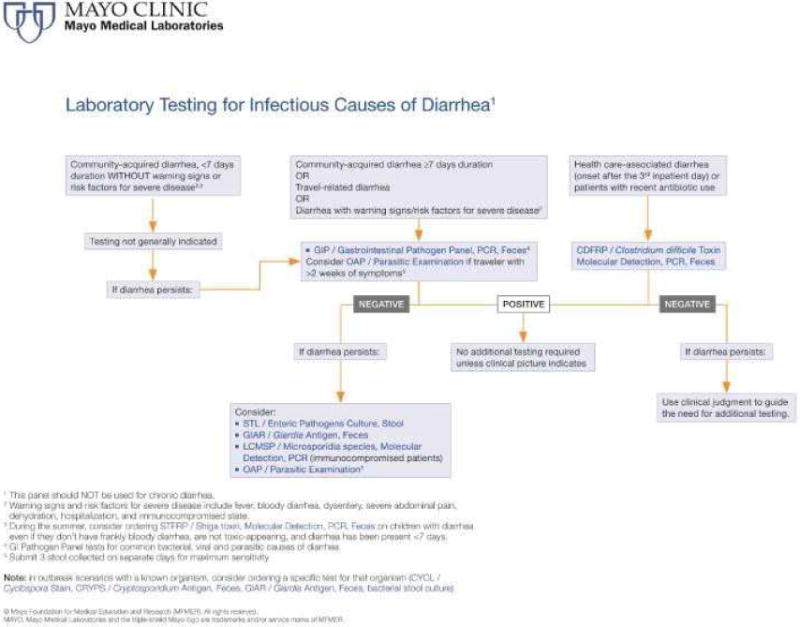

Unlike panels for testing positive blood culture bottles, gastrointestinal and respiratory panels are not designed as supplemental tests, but instead are being utilized as stand-alone tests. For example, instead of ordering stool cultures and specific testing for Giardia and Cryptosporidium species, a broad gastrointestinal panel might be considered. Examples of broad molecular panels for testing gastrointestinal pathogens are shown in Table 2. These panels typically include bacteria, along with viruses and, in some cases, parasites as well, and they perform as well as traditional diagnostic techniques.6 The broadest panel, which takes about an hour, is the FilmArray® Gastrointestinal (GI) Panel (BioFire Diagnostics, LLC). The xTAG® Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel (Luminex Corporation), is slightly narrower in terms of the organisms targeted and takes a little over five hours. Finally, the Verigene® Enteric Pathogens Test (EP, Nanosphere, Inc.) takes approximately two hours and includes bacteria and a couple of viruses, but not parasites. The ideal composition of these panels remains to be determined – a larger panel is not always better and may lead to clinical confusion. As with tests for positive blood culture bottles, these molecular panels are quite expensive, so test utilization algorithms need adherence to ensure that they are used appropriately. For example, testing with a molecular gastrointestinal panel would not be necessary in an immunocompetent outpatient with community-associated diarrhea of short duration in the absence of fever, bloody diarrhea, dysentery, severe abdominal pain, or dehydration (Figure 1).7

Table 2.

Targets of large molecular panels for testing stool

| Target | Targets on panel | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| FilmArray Gastrointestinal (GI) Panel (BioFire Diagnostics, LLC) | xTAG® Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel (Luminex Corporation) | Verigene® Enteric Pathogens Test (EP) (Nanosphere) | |

| Bacteria | |||

| Campylobacter species | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Clostridium difficile | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | ✓ | ||

| Salmonella species | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Vibrio cholerae | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Vibrio species | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli | ✓ | ||

| Enteropathogenic E. coli | ✓ | ||

| Enterotoxigenic E. coli | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Shiga toxin-producing E. coli | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| E. coli 0157 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Shigella species (enteroinvasive E. coli) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Parasites | |||

| Cryptosporidium species | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Cyclospora cayetanensis | ✓ | ||

| Entamoeba histolytica | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Giardia lamblia | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Viruses | |||

| Adenovirus serotypes 40/41 | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Astrovirus | ✓ | ||

| Norovirus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Rotavirus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Sapovirus | ✓ | ||

Figure 1. Test ordering guidance for infectious diarrhea7.

A general guide to laboratory testing for infectious causes of diarrhea is shown. Note that culture is necessitated in cases where antimicrobial susceptibility testing is required, and can be tailored to isolation of the organism(s) detected by the molecular panel (i.e., reflexive culture). The same approach can be used if isolates are needed by public health departments [i.e., stool testing positive by a multiplex GI panel can be submitted to a public health department where culture can be performed to isolate the organism(s) detected.]

However, for patients who qualify for these testing methods, depending on the platform, specimens can be tested for as many as 22 organisms in just over an hour of receipt in the laboratory. This enables a final diagnosis during a single episode of care, depending on the system set up. Clearly, test utilization strategies are important to have in place with these broad panels,8 and in addition, help may be needed for clinicians to interpret results for pathogens their laboratory has not historically detected. Clinicians should keep in mind that these gastrointestinal panels are not designed for testing patients with chronic diarrhea and that they do not detect every potential gastrointestinal pathogen. Clinical microbiology laboratories need to coordinate with clinicians and information technology to develop strategies to ensure appropriate test ordering and interpretation. An example of test ordering guidance for acute diarrhea is shown in Figure 1.7

Another example of a rapid panel-based molecular diagnostic test is the FilmArray® Meningitis/Encephalitis test, which detects Escherichia coli K1, Haemophilus influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes, Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus, enterovirus, herpes simplex virus 1, herpes simplex virus 2, human herpesvirus, human parechovirus, varicella zoster virus and Cryptococcus neoformans/gattii in cerebrospinal fluid. In a recent study, 48 cerebrospinal fluid specimens from 25 patients with meningitis, and 23 with encephalitis were evaluated with this panel.9 Potential pathogens were identified in 14 samples by routine evaluation, and 13 by using the multiplex panel [herpes simplex virus 2 (3), varicella zoster virus (3), S. pneumoniae (4), herpes simplex virus 1 (1), enterovirus (1), and C. gattii/neoformans (1)]. The PCR panel detected pathogens not detected by those ordered in routine clinical practice in five cases, including varicella zoster virus (2), herpes simplex virus (2) and S. pneumoniae (1). In one patient each with herpes simplex virus type 2 and varicella zoster virus, no routine testing for these organisms had been ordered, however. Notably, routine testing identified pathogens, including West Nile virus (4) and Histoplasma capsulatum (1), in five of 33 multiplex PCR negative samples. Overall, although such an approach will enable more rapid diagnosis than previously possible, empiric treatment strategies (e.g., for bacterial meningitis and herpes encephalitis) may limit the effects of such panels on improved patient outcomes. Furthermore, clinicians should keep in mind that these panels are not designed for testing patients with chronic meningitis or encephalitis and may miss some causes of acute central nervous system infection (e.g., West Nile virus). Finally, as of today, none of these panels are Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-waived, which would enable their performance as point-of-care tests, potentially maximizing their clinical utility. For example, a physician performing a spinal tap could immediately run a rapid panel-based molecular diagnostic test on the retrieved cerebrospinal fluid.

Point-of-Care Molecular Testing

Although rapid panel-based molecular diagnostic tests are not currently CLIA-waived, there are now CLIA-waived rapid point-of-care nucleic acid amplification tests available. These assays take the expert testing traditionally offered in clinical microbiology laboratories and bring them closer to the patient. For example, assays are now available for Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus) as well as influenza on the cobas Liat PCR System (Roche Diagnostics) and the Alere I® system (Alere Inc.). These tests use small, automated, closed nucleic acid amplification instruments that process one specimen at a time in a matter of minutes, and require relatively little training for use. These assays have the accuracy of those traditionally performed in clinical microbiology laboratories.10-13 These assays and similar instruments provide important advances in nucleic acid amplification technology which should be helpful in doctors’ offices, urgent care centers, emergency departments, hospital laboratories, pharmacies, and other point-of-care settings. Paired with process changes, these assays offer patients the opportunity to collect their own throat or nasopharyngeal swabs or for parents to collect their children’s – both of which have been shown to yield accurate results.14,15 These technologies have the potential to enable novel and innovative ways to deliver patient care.

Proteomics Revolutionize Identification of Cultured Bacteria

This section is based, in part, on Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry in clinical microbiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Aug; 57(4):564-72.

Despite the advent of an increasing number of molecular diagnostics, such as those discussed above, it is unlikely that cultures will disappear anytime soon.16 Cultures detect a variety of types of organisms, making it nearly impossible to completely replicate their utility based on current technology, price, and turnaround time, with non-culture based approaches. And, they enable phenotypic susceptibility testing. Their shortcoming is a relatively slow turnaround-time, due to the time it takes organisms to grow and the time taken to make an identification. The second issue has been addressed with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), a technology now routinely used in many large clinical microbiology laboratories.

Identification of cultured bacteria and fungi was traditionally a complex, algorithmic task, involving interpretation of colony morphology, hemolysis patterns, stains, and numerous biochemical tests performed on colonies. Much of this testing took a day or longer, prolonging time-to-identification. In the interim, clinicians were left with preliminary general identifications such as “Gram-positive cocci”. Even testing performed on automated instruments, such as the VITEK® (bioMérieux Inc.), BD Phoenix™ Automated Microbiology System (BD,) or MicroScan® (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc.) is not rapid and often requires knowledge of the organism-type being tested (e.g., Gram-negative bacilli) before the process can begin. With MALDI-TOF MS, colonies growing in culture are economically and correctly identified in as short a time as three minutes, without technologists needing to first verify the type of organism (e.g., Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacterium or even yeast) being tested. The product of recent developments in bioinformatics and mass spectrometry, MALDI-TOF MS has transformed bacterial and fungal identification.16

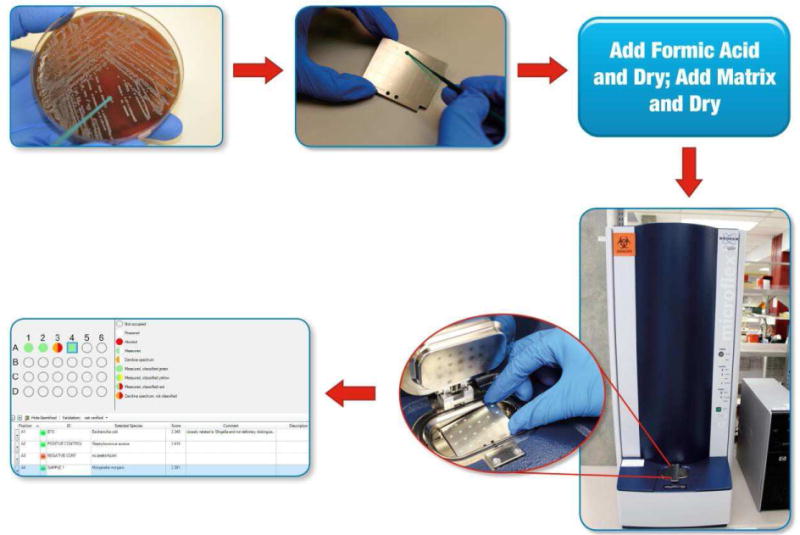

The simplest MALDI-TOF MS applications test colonies of bacteria or yeast without intricate preparation and using negligible consumables, providing fast, cost-effective identification. Because of the cost savings, MALDI-TOF MS is an exception to many new technologies.17 Testing begins by “picking” an unknown colony from a culture plate to a “spot” on a MALDI-TOF MS target plate (Figure 2).18 The cells may be treated with formic acid and allowed to dry on the target plate; they are subsequently overlain with a small amount of matrix. Following a short drying period, the plate is placed in a mass spectrometry instrument.

Figure 2.

18 A bacterial or fungal colony (typically single) is “picked” from a culture plate to a “spot” on a MALDI-TOF MS target plate (a reusable or disposable plate with a number of test spots) using a wooden or plastic stick, pipette tip, or loop. One or many isolates may be tested at a time. Cells may be treated with formic acid on the target plate. The spot is then overlain with matrix. Following a short drying period, the plate is placed in the mass spectrometer for analysis. A mass spectrum is generated and automatically compared against a database of mass spectra by the software, resulting in identification of the organism (Morganella morganii in position A4 in the example). (Adapted from Communiqué article, January 2013. Theel ES. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry for the identification of bacterial and yeast isolates. www.mayomedicallaboratories.com/articles/communique/2013/01-maldi-tof-mass-spectrometry.)

The acronym “MALDI” refers to the Matrix, which Assists in the Laser Desorption and Ionization of microbial analytes. The matrix (typically, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid dissolved in trifluoroacetic acid and acetonitrile) separates microbial molecules from each other. Matrix and microbial molecules on the target plate are subsequently desorbed via laser-pulses, with most of the energy being absorbed by the matrix, converting it to an ionized state. Through random collision in the gas phase, the charge is transferred from matrix to microbial molecules. The ionized microbial proteins are accelerated through a positively charged electrostatic field into a tube under a vacuum, referred to as a Time-Of-Flight or “TOF” mass analyzer. The ions travel toward an ion detector, with small analytes arriving at the detector first, followed by increasingly larger analytes. Analytes within the specified mass range are measured, most of which are ribosomal proteins. A mass spectrum is produced, representing the number of ions of a given mass detected over time.

The mass spectrum provides a profile or fingerprint of the unknown microorganism. Mass spectra are unique to individual microorganism-types, with peaks specific to complexes, genera, and species. Once generated, each test isolate’s mass spectrum is compared to a database of reference spectra to determine its relatedness to spectra in the database; a list of most closely-related organisms is produced, each with a numeric ranking (score or percent) indicating the confidence in identification. Depending on how high the value is, the organism is identified at the complex, genus, or species level. Well-curated spectral databases representing all-inclusive collections of properly named and clinically-relevant microorganisms are necessary. In the absence of mass spectral entries for a particular species in a database, entries may be added by the user. It takes only about three minutes per isolate from inserting the plate into the instrument to achieve a final result. The technology is “green,” with reusable target plates available and few disposables required, and no expertise in mass spectrometry is needed.

Two FDA-cleared MALDI-TOF MS systems are available, the VITEK® MS system (bioMérieux Inc.) and the MALDI Biotyper® CA system (Bruker Daltonics Inc.), differing in algorithms and databases used to identify organisms and in instrumentation. MALDI-TOF MS performs at least as well as automated biochemical identification systems for commonly-encountered bacteria,19-21 and better for unusual organisms, such as anaerobic bacteria,22 Corynebacterium species,23 mycobacteria, Nocardia species,24 yeasts,25 and even filamentous fungi.26

Compared to standard methods, MALDI-TOF MS improves turnaround-time for identification of bacteria and fungi by an average of 1.45 days,17 and, since only a small amount of organism is needed, testing can be performed directly from primary culture plates, whereas other methods may require subculture, reducing time-to-identification.

MALDI-TOF MS reagent costs are inexpensive; and use of this technology reduces reagent and labor costs for identification.17 An estimated 87% of isolates are identified on the first day (compared to 9% with standard techniques), with final identification available a day earlier than conventional methods for most organisms, and several days earlier for fastidious, biochemically inert, or slow-growing organisms.17 Anaerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi are identified just as quickly as conventional bacteria. Sequencing and biochemical costs are avoided for esoteric organisms. Quality control and laboratory technologist training/labor for replaced/retired tests are eliminated, and waste disposal is decreased. Limitations include low sensitivity to detect organisms in most clinical specimens directly (i.e., without culture) which requires preliminary growth of organisms prior to application, and second, the method currently does not deliver susceptibility results.

MALDI-TOF MS is a major advance for rapid and accurate identification of cultured bacteria and fungi. However, use of this technology may,27 or may not,28 impact clinical outcomes, depending on a range of factors, including antimicrobial stewardship systems in place at individual institutions, details in how MALDI-TOF MS is performed, antimicrobial resistance rates, and the patient mix. Innovative applications, such as the testing of subculture plates from positive blood culture bottles after a brief incubation, shorten time-to-identification using MALDI-TOF MS.29 With its accuracy, breadth, and cost-savings, this technology is unquestionably valuable for laboratories able to access it.

Laboratory Automation

Laboratory automation, involving robotic specimen aliquoting, testing, and reporting, is the standard in chemistry laboratories today. These innovations have been slowly implemented in clinical bacteriology laboratories due to the need for a large number of diverse human activities not easily amenable to automation, and due to the wide variety of specimen types and specimen collection containers used.30 Several companies have developed, and are continuing to refine automation systems for use in clinical microbiology laboratories. Examples include the BD Kiestra™ automation system (BD), the WASP system (COPAN Diagnostics Inc.) and the RECITALS™ system (i2a Diagnostics). These systems include automation of specimen streaking onto culture plates, with conveyor belt systems that place the culture plates into automated incubators where the plates are periodically imaged using robotics associated within the incubators. Technologists then view the plate images on computer screens, a function that may ultimately be, at least in part, handled by automated imagers. Technologists can interact with the screen to select colonies for MALDI-TOF MS, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and/or other testing. Systems may ultimately include automated MALDI-TOF MS and antimicrobial susceptibility testing “pickers” that will use robotics to move selected colonies to MALDI-TOF MS and susceptibility systems. Clinicians can anticipate the possibility that such systems, when fully functional, may provide more expedient results, and certainly, will be able to provide them 24/7. These associated digital plate images may allow earlier “real-time” recognition of growth, and may enhance sharing of plate images with clinical teams which are increasingly physically separated from their laboratories.30 The systems are, however, large, quite expensive, have limited throughput, require back-up systems in case of failure, and do not accommodate all specimen and culture types (e.g., anaerobic culture). Ultimately, whether or not there will be benefits gained to improve patient care remains to be determined,30 but at least for large, centralized laboratories, clinicians can expect to see such systems in place today or in the near future.

Looking Ahead

In the current era of antimicrobial resistance, a clinical need not completely addressed by these aforementioned strategies is rapid phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing. For some resistance mechanisms, such as methicillin resistance in staphylococci, or vancomycin resistance in enterococci, molecular methods may be fairly easily applied, providing rapid susceptibility results, albeit of a limited spectrum. But for many other types of bacteria and most other types of antimicrobial agents, molecular testing has a limited role in providing the full susceptibility profile provided by conventional phenotypic susceptibility testing. This is due to the large number of mechanisms that confer antimicrobial resistance in clinically-relevant bacteria, including antibiotic-modifying enzymes such as β-lactamases, of which over 1,500 have been described. Also relevant are the porin mutations in Gram-negative bacteria, antibiotic-efflux pumps, and multiple mutations involved in target binding site modification. In addition, in many bacteria, more than one mechanism may be simultaneously present, and the net effect of an identified genetic resistance mechanism (if it can be identified - many are as-yet uncharacterized) may be unclear in determining whether or not a drug may be used clinically. Given the complexity of this situation, especially in the case of Enterobacteriaceae, and non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli such as Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, efforts and new strategies have turned to providing rapid growth-based phenotypic susceptibility testing, wherein organisms are grown with and without individual antibiotics. Traditional strategies to accomplish this this, including automated methods such as the VITEK® (bioMérieux Inc.), BD Phoenix™ Automated Microbiology System (BD) and MicroScan® (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc.), and manual methods such as gradient-strip, or disk diffusion testing are not rapid. A number of companies are developing automated instruments and systems that rapidly assess growth using high-resolution imaging, individual cell mass measurement, and other sophisticated methods of cell counting. Some are being developed for testing positive blood culture bottles, some for testing urine, and others for testing bacterial colonies. Many laboratories are using or exploring strategies to more rapidly provide phenotypic susceptibility testing, using available technology. Examples include moving straight from positive blood culture bottles to currently available automated susceptibility instruments,31 or placing antibiotic disks directly on subculture plates from positive blood culture bottles alongside MALDI-TOF MS performed on the subculture plates after a short duration of incubation.29

Finally, advances in whole-genome sequencing and metagenomics are under development for clinical bacteriology testing. Whole-genome sequencing-based strategies are likely to replace traditional methods for typing bacteria, such as pulsed field gel electrophoresis, used for outbreak investigation.32,33 Although there are as yet no commercially available systems for sequencing in clinical bacteriology laboratories, the availability of benchtop sequencers such as the MiSeq system (Illumina Inc.), the Ion Torrent PGM™ (Life Technologies), the Ion Proton™ System (Life Technologies), the PacBio RS II (Pacific Biosciences), the Sequel System (Pacific Biosciences), GridION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies), MinION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies), and PromethION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies), offers the possibility of bringing whole-genome sequencing to clinical bacteriology. Nevertheless, it is yet undetermined whether typing using whole-genome sequencing (versus conventional strategies) will be associated with increased prevention of transmission events, resulting in overall cost savings.34 Not only can such sequences be used for typing to determine strain relatedness, but the same sequence can theoretically be used for resistance35,36 and virulence profiling. These endeavors are currently challenging, due to limitations in bioinformatics pipelines and databases, and gaps in knowledge vis-à-vis interpretation of the generated data. As mentioned above, antimicrobial susceptibility testing is nuanced; and genotypic results may not always provide a quantitative measure of true susceptibility. It may not be clear, for example, whether the presence of a particular gene or mutation confers phenotypic resistance.34 Sequencing may fail to predict resistance if the genotypic basis of that resistance is not yet genetically characterized, or is not represented in the databases used.34 Nevertheless, with carefully constructed systems, it may be possible to use whole-genome sequencing for antimicrobial susceptibility testing.37 Whole-genome sequencing may be particularly useful for organisms such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which are slow-growing, and for which phenotypic susceptibility testing is slow and molecular mechanisms of resistance, which are typically mutational, have been fairly well characterized and correlated with phenotypic susceptibility.34 Although the cost of sequencing per se has been decreasing over time, the requirements for bioinformatics expertise, computer hardware and software, databases, etc. makes this type of analysis expensive today.38 Finally, clinicians should be aware that unlike the previously discussed rapid diagnostic tests, current whole genome sequencing-based analyses are not rapid.

A final application of massively parallel sequencing is agnostic metagenomics, an approach in which all DNA in a clinical specimen is sequenced, human DNA sequences are “subtracted,” and the leftover non-human DNA is analyzed, potentially revealing the DNA of previously undetected microorganisms. This agnostic approach was used to diagnose neuroleptospirosis in a New England Journal of Medicine case report from 2014,39 and tularemia in a Journal of Clinical Microbiology case report from 2012.40 This technology remains under development as design issues and strategies to provide clinically-useful data interpretation are addressed, including sensitivity and specificity, and methods to improve recovery of microbial DNA to enhance detection in a large background of human DNA. Also, it is challenging to eliminate background microbial DNA from reagents used for this testing (which are frequently contaminated with bacterial DNA). Ultimately, whether this approach will provide actionable information that improves patient care in a cost-effective manner needs to be addressed, as will its advantages over other agnostic approaches, including broad-range bacterial PCR, and PCR electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry.1,41-43

Overall, although whole-genome sequencing and metagenomic analysis holds promise for clinical bacteriology testing, difficulties remain, including the lack of availability of standardized bioinformatics pipelines and technical procedures, limitations of existing reference databases, and the absence of established quality control measures which are critical to patient care.34 Finally, clinicians should be aware that costs are substantial, and turnaround times, at least today, are long.34

There are several limitations or concerns regarding advances in bacteriology diagnostics. A large percentage of care of American patients occurs in rural or community hospitals, and some of the new technologies discussed herein are challenging to “deploy” in these settings. MALDI-TOF MS instruments, for example, are quite expensive, although the capital equipment cost can be paid off through savings in reagents and labor. Nevertheless, this technology may not be available in smaller laboratories and therefore to the patients they serve. However, some of the new technologies discussed above, including the easy-to-use point-of-care molecular diagnostics have the potential to revolutionize diagnostics in smaller as well as resource-limited settings (although costs must be addressed).

Conclusion

A number of new technologies have recently been introduced in modern clinical bacteriology laboratories, including panel-based molecular diagnostics for numerous applications, rapid point-of-care nucleic acid amplification tests, MALDI-TOF MS, and laboratory automation. Several novel technologies are also under development, including rapid phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing, whole genome sequencing, and metagenomic analysis for the agnostic detection of bacteria (and other microorganisms) in clinical specimens. Clinicians must be aware of the rapid pace of new development in their bacteriology laboratory. Antimicrobial stewardship programs should coordinate with their laboratories to ensure that new technology is optimally affecting patient care.

Highlights.

Panel-based molecular diagnostics are available for numerous applications, including, but not limited to, detection of bacteria and antimicrobial resistance markers in positive blood culture bottles, detection of acute gastroenteritis pathogens in stool, and detection of select causes of acute meningitis and encephalitis in cerebrospinal fluid.

Rapid point-of-care nucleic acid amplification tests are available, bringing the accuracy of sophisticated molecular diagnostics to the bedside.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) has been implemented into many clinical microbiology laboratories and is associated with rapid, cost-effective, and accurate identification of bacteria recovered in cultures.

Laboratory automation, standard in chemistry laboratories, is now available for clinical bacteriology laboratories.

Rapid phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing, whole-genome sequencing, and metagenomic analysis are under development for clinical diagnostic testing.

Cost-effectiveness and effect on clinical outcomes of novel technologies needs to be evaluated before widespread adoption; involvement of an antimicrobial stewardship team can be helpful.

Acknowledgments

I thank Drs. Nancy L. Wengenack, Bobbi S. Pritt, Matthew J. Binnicker, Priya Sampathkumar, and Ritu Banerjee, Mr. Scott A. Cunningham, and Mss. Emily A. Vetter, Brenda L. Dylla, and Sherry M. Ihde for their thoughtful reviews of this manuscript. I also thank the Antimicrobial Resistance Leadership Group of the National Institutes of Health (UM1 AI104681) and the Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine for their support.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Patel reports grants from BioFire, Check-Points, Curetis, 3M, Merck, Hutchison Biofilm Medical Solutions, Accelerate Diagnostics, Allergan, and The Medicines Company. Dr. Patel is a consultant to Curetis, Roche, Qvella, and Diaxonhit; monies are paid to Mayo Clinic. In addition, Dr. Patel has a patent on Bordetella pertussis/parapertussis PCR issued, a patent on a device/method for sonication with royalties paid by Samsung to Mayo Clinic, and a patent on an anti-biofilm substance issued. Dr. Patel serves on an Actelion data monitoring board. Dr. Patel receives travel reimbursement and an editor’s stipend from ASM and IDSA, and honoraria from the USMLE, Up-to-Date and the Infectious Diseases Board Review Course.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BCID

Blood Culture Identification

- CLIA

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- FDA

United States Food and Drug Administration

- MALDI-TOF MS

matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shrestha NK, Ledtke CS, Wang H, et al. Heart valve culture and sequencing to identify the infective endocarditis pathogen in surgically treated patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cazanave C, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Hanssen AD, et al. Rapid molecular microbiologic diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(7):2280–2287. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00335-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomez E, Cazanave C, Cunningham SA, et al. Prosthetic joint infection diagnosis using broad-range PCR of biofilms dislodged from knee and hip arthroplasty surfaces using sonication. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(11):3501–3508. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00834-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee R, Teng CB, Cunningham SA, et al. Randomized trial of rapid multiplex polymerase chain reaction-based blood culture identification and susceptibility testing. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(7):1071–1080. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria.

- 6.Khare R, Espy MJ, Cebelinski E, et al. Comparative evaluation of two commercial multiplex panels for detection of gastrointestinal pathogens by use of clinical stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(10):3667–3673. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01637-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laboratories MM. Laboratory Testing for Infectious Causes of Diarrhea. In: Diarrhea LTfICo, editor. Mayo Medical Laboratories Online Test Catalog. Mayo Medical Laboratories; 2015. (Test algorithm chart). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schreckenberger PC, McAdam AJ. Point-counterpoint: Large multiplex PCR panels should be first line tests for detection of respiratory and intestinal pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(10):3110–3115. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00382-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wootton SH, Aguilera E, Salazar L, Hemmert AC, Hasbun R. Enhancing pathogen identification in patients with meningitis and a negative Gram stain using the BioFire FilmArray((R)) Meningitis/Encephalitis panel. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2016;15:26. doi: 10.1186/s12941-016-0137-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uhl JR, Patel R. Fifteen-minute detection of Streptococcus pyogenes in throat swabs by use of a commercially available point-of-care PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(3):815. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03387-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Binnicker MJ, Espy MJ, Irish CL, Vetter EA. Direct detection of influenza A and B viruses in less than 20 minutes using a commercially available rapid PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(7):2353–2354. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00791-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen DM, Russo ME, Jaggi P, Kline J, Gluckman W, Parekh A. Multicenter clinical evaluation of the novel Alere i Strep A isothermal nucleic acid amplification test. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(7):2258–2261. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00490-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen Van JC, Camelena F, Dahoun M, et al. Prospective evaluation of the Alere i Influenza A&B nucleic acid amplification versus Xpert Flu/RSV. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray MA, Schulz LA, Furst JW, et al. Equal performance of self-collected and health care worker-collected pharyngeal swabs for group A streptococcus testing by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(2):573–578. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02500-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhiman N, Miller RM, Finley JL, et al. Effectiveness of patient-collected swabs for influenza testing. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(6):548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel R. MALDI-TOF MS for the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):100–111. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.221770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan KE, Ellis BC, Lee R, Stamper PD, Zhang SX, Carroll KC. Prospective evaluation of a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry system in a hospital clinical microbiology laboratory for identification of bacteria and yeasts: a bench-by-bench study for assessing the impact on time to identification and cost-effectiveness. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(10):3301–3308. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01405-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theel ES. Communiqué. Mayo Foundation For Medical Education And Research; 2013. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry for the Identificaiton of Bacterial and Yeast Isolates. January 2013 ed. Communiqué. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saffert RT, Cunningham SA, Ihde SM, Jobe KE, Mandrekar J, Patel R. Comparison of Bruker Biotyper matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometer to BD Phoenix automated microbiology system for identification of Gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(3):887–892. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01890-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alatoom AA, Cunningham SA, Ihde SM, Mandrekar J, Patel R. Comparison of direct colony method versus extraction method for identification of Gram-positive cocci by use of Bruker Biotyper matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(8):2868–2873. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00506-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marko DC, Saffert RT, Cunningham SA, et al. Evaluation of the Bruker Biotyper and Vitek MS matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry systems for identification of nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli isolated from cultures from cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(6):2034–2039. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00330-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitt BH, Cunningham SA, Dailey AL, Gustafson DR, Patel R. Identification of anaerobic bacteria by Bruker Biotyper matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry with on-plate formic acid preparation. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(3):782–786. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02420-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alatoom AA, Cazanave CJ, Cunningham SA, Ihde SM, Patel R. Identification of non-diphtheriae Corynebacterium by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(1):160–163. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05889-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buckwalter SP, Olson SL, Connelly BJ, et al. Evaluation of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for identification of Mycobacterium species, Nocardia species, and other aerobic actinomycetes. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(2):376–384. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02128-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhiman N, Hall L, Wohlfiel SL, Buckwalter SP, Wengenack NL. Performance and cost analysis of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for routine identification of yeast. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(4):1614–1616. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02381-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theel ES, Hall L, Mandrekar J, Wengenack NL. Dermatophyte identification using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(12):4067–4071. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01280-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang AM, Newton D, Kunapuli A, et al. Impact of rapid organism identification via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight combined with antimicrobial stewardship team intervention in adult patients with bacteremia and candidemia. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(9):1237–1245. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buss BA, Schulz LT, Reed KD, Fox BC. MALDI-TOF utility in a region with low antibacterial resistance rates. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(5):666–667. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altun O, Botero-Kleiven S, Carlsson S, Ullberg M, Ozenci V. Rapid identification of bacteria from positive blood culture bottles by MALDI-TOF MS following short-term incubation on solid media. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64(11):1346–1352. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledeboer NA, Dallas SD. The automated clinical microbiology laboratory: fact or fantasy? J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(9):3140–3146. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00686-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez KK, Olsen RJ, Musick WL, et al. Integrating rapid diagnostics and antimicrobial stewardship improves outcomes in patients with antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteremia. J Infect. 2014;69(3):216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunn JR. Whole-Genome Sequencing: Opportunities and Challenges for Public Health, Food-borne Outbreak Investigations, and the Global Food Supply. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(4):499–501. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azarian T, Cook RL, Johnson JA, et al. Whole-genome sequencing for outbreak investigations of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the neonatal intensive care unit: time for routine practice? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(7):777–785. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lefterova MI, Suarez CJ, Banaei N, Pinsky BA. Next-generation sequencing for infectious disease diagnosis and management: A report of the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17(6):623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norgan AP, Freese JM, Tuin PM, Cunningham SA, Jeraldo PR, Patel R. Carbapenem-and colistin-resistant Enterobacter cloacae from Delta, Colorado, in 2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016 doi: 10.1128/AAC.03055-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadarangani SP, Cunningham SA, Jeraldo PR, Wilson JW, Khare R, Patel R. Metronidazole-and carbapenem-resistant Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron isolated in Rochester, Minnesota, in 2014. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(7):4157–4161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00677-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon NC, Price JR, Cole K, et al. Prediction of Staphylococcus aureus antimicrobial resistance by whole-genome sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(4):1182–1191. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03117-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sboner A, Mu XJ, Greenbaum D, Auerbach RK, Gerstein MB. The real cost of sequencing: higher than you think! Genome Biol. 2011;12(8):125. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson MR, Naccache SN, Samayoa E, et al. Actionable diagnosis of neuroleptospirosis by next-generation sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(25):2408–2417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuroda M, Sekizuka T, Shinya F, et al. Detection of a possible bioterrorism agent, Francisella sp. in a clinical specimen by use of next-generation direct DNA sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(5):1810–1812. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06715-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Relman DA. Actionable sequence data on infectious diseases in the clinical workplace. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):38–40. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.229211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallet F, Herwegh S, Decoene C, Courcol RJ. PCR-electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry: a new tool for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis from heart valves. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76(2):125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brinkman CL, Vergidis P, Uhl JR, et al. PCR-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry for direct detection of pathogens and antimicrobial resistance from heart valves in patients with infective endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(7):2040–2046. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00304-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]