Abstract

Objective

To investigate how inpatient palliative care teams nationwide currently screen for and treat psychological distress.

Methods

A web-based survey was sent to inpatient palliative care providers of all disciplines nationwide asking about their practice patterns regarding psychological assessment and treatment. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample and responses, and analysis of variance was conducted to determine whether certain disciplines were more likely to utilize specific treatment modalities.

Results

A total of N = 236 respondents were included in the final analyses. Providers reported that they encounter psychological distress regularly in their practice and that they screen for distress using multiple methods. When psychological distress is detected, providers reported referring patients to an average of 3 different providers (standard deviation = 1.46), most frequently a social worker (69.6%) or chaplain (65.3%) on the palliative care team. A total of 84.6% of physicians and 54.5% of nurse practitioners reported that they prescribe anxiolytics or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to patients experiencing psychological distress.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study revealed significant variability and redundancy in how palliative care teams currently manage psychological distress. The lack of consistency potentially stems from the variability in the composition of palliative care teams across care settings and the lack of scientific evidence for best practices in psychological care in palliative care. Future research is needed to establish best practices in the screening and treatment of psychological distress for patients receiving palliative care.

Keywords: palliative care, psychological distress, psychological treatment, psychological assessment, psychological screening

Introduction

Palliative care seeks to relieve suffering in patients with serious or life-threatening illness and their families through comprehensive assessment and treatment of physical, psychosocial, and spiritual symptoms.1,2 As our population continues to age, the number of adults living with serious illness, such as heart failure, end-stage renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and cancer, will also rise. Patients with serious illness experience high levels of symptom burden and diminished quality of life, as well as an increased prevalence of psychological distress such as depression and anxiety.3–5 Furthermore, caregivers of patients with serious illness also experience higher rates of psychological symptoms and are at increased risk of developing anxiety and depression.6,7 Guidelines from the National Consensus Project and National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization strongly recommend that the interdisciplinary palliative care team “assesses and addresses psychological and psychiatric aspects of care based upon the best available evidence to maximize patient and family coping and quality of life.”8(p64) However, given the heterogeneity of how palliative care teams are staffed in hospitals and other care settings,9 it is unclear what psychological assessment techniques and interventions are actually being delivered and by whom.

A recent systematic review of palliative care interventions revealed that multicomponent palliative care interventions that purport to provide psychological care routinely fail to document the type of psychological treatment being provided, who is providing it, and whether it is effective.10 This review further revealed that in the research setting, the most frequent mental health screen was the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale,10 a multidimensional palliative care screening instrument that is commonly used despite the fact that its reliability and validity as a screening tool for psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression has not been established.11 While treating psychological distress is a critical component of what palliative care teams do, it is unclear whether teams in practice are currently doing so based on the “best available evidence.”

Furthermore, while pharmacologic approaches such as anxiolytics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly employed to help manage psychological distress,12,13 this approach can cause harm by increasing a patient’s risk of falls, delirium, and polypharmacy.14–16 In one study of the palliative care patients, oral benzodiazepine use was associated with negative outcomes including worsening performance status and gastrointestinal symptoms.17 Nonpharmacological approaches to managing psychological distress exist. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has proven efficacy for managing psychological distress in many populations18 and does not carry the risks associated with medication use. It is unclear, however, whether palliative care teams currently employ evidence-informed, nonpharmacological techniques, such as CBT, to manage psychological distress in their respective patients.

Recognizing that the results of the 2017 systematic review may have only been capturing research-based interventions rather than what is happening in actual clinical practice, this study sought to investigate how inpatient palliative care teams nationwide currently screen for and treat psychological distress in their respective practices. By asking professionals currently serving on palliative care teams how they assess and treat psychological distress in patients with advanced chronic illness, we aim to generate a better understanding of the current practices employed by inpatient palliative care teams when addressing mental health issues in their respective patient populations.

Methods

Palliative care providers were recruited from multiple sources, including professional contacts of the authors, e-mail listservs of palliative care nurses and social workers including the Zelda Foster Database and the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association listserv, Internet searches of palliative care providers based on the Center for the Advancement of Palliative Care “Where to get palliative care” web page (https://getpalliativecare.org/providers/), and word of mouth. Providers who received the recruitment e-mail were encouraged to forward the e-mail to other colleagues who may be eligible for and interested in participating in the study. Due to this “snowball” method of recruitment, it is unknown how many people received an invitation to participate in the study.

The study was conducted using the Qualtrics platform and was reviewed and approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College Human Research Protection Office. An e-mail was sent to potential participants informing them of the study that included a link to the online survey. Individuals who visited the site were first asked whether they were currently seeing patients as part of an inpatient palliative care team. If they answered no to this question, they were ineligible. Prospective participants who answered “yes” to the first question were subsequently asked if they had provided care to patients on an inpatient palliative care team for at least 1 year. If they responded no, they were also screened out of the study.

Overall, n = 437 individuals visited the Qualtrics website, and 167 were ineligible to participate because they did not currently serve on a palliative care team or had been serving on a palliative care team for <1 year. An additional 34 individuals were removed from the analytic sample because they answered the 2 screening questions correctly (and were therefore eligible to participate) but answered none of the survey questions. Analyses were conducted on the remaining 236 respondents who answered at least some of survey items. Sample size is reported for each analysis because some participants did not complete the entire survey but provided sufficient information to be included in individual analyses.

Measures

Participants were asked a series of questions regarding their current practices for screening and treating patients with psychological distress. The survey instrument is available upon request from the corresponding author. We were particularly interested in practice patterns surrounding a common type of psychological distress found in patients receiving palliative care: anxiety. We therefore queried respondents about how they managed anxiety symptoms specifically in addition to asking more general questions about psychological distress. Information about the composition of the palliative care team and background information of participants (eg, years in practice, number of hours spent seeing patients each week) were also collected to characterize the sample.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed to characterize the data. Analyses of variances (ANOVAs) were performed to analyze whether particular disciplines were more likely to engage in multiple methods of nonpharmacological treatments or empirically supported nonpharmacological treatments. Empirically supported nonpharmacological treatments were defined based on the American Psychological Association’s Society of Clinical Psychology’s website,19 which evaluated psychological treatments for specific disorders based on the Chambless and Hollon’s20 criteria. The website lists only CBT as an empirically supported treatment with sufficient evidence for generalized anxiety disorder; however, because this study was looking at how symptoms of anxiety are treated rather than psychological disorders that meet full diagnostic criteria, we included the common components of CBT (distraction techniques, relaxation techniques, and mindfulness meditation techniques) as empirically “informed” treatments for symptoms of anxiety. Post hoc analyses were conducted to better understand which treatments were most likely to be administered by each discipline.

Results

Table 1 shows the breakdown of participants by discipline, hospital setting (rural, suburban, and urban), gender, hours per week spent seeing patients, and type of hospital (academic medical center, community hospital, Veterans Affairs Hospital, comprehensive cancer, and other). Nursing and social work were collapsed in this table to include all nursing degrees (registered nurses, nurse practitioners, and clinical nurse specialists) and all social work degrees (MSW and LCSW). In subsequent analyses, registered nurses were separated from nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists. Clinical nurse specialists was a frequent write-in response and was not initially included on the survey as an option to be selected.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Discipline | |

| MD | 65 (28.8) |

| Advance practice nursea | 49 (22.0) |

| Social worka | 42 (18.6) |

| Psychologist | 20 (8.8) |

| Chaplain | 13 (5.7) |

| RN | 17 (7.6) |

| Otherb | 17 (7.6) |

| Total | 226 |

| Hospital setting | |

| Urban | 145 (65.0) |

| Suburban | 53 (23.8) |

| Rural | 23 (10.3) |

| Total | 223 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 168 (75.3) |

| Male | 54 (24.2) |

| Total | 223 |

| Hours per week seeing patients | |

| 1–15 | 38 (17.0) |

| 16–30 | 88 (39.3) |

| 31–45 | 73 (32.6) |

| 46+ | 18 (8.0) |

| Total | 224 |

| Type of hospital | |

| Academic medical center | 93 (41.5) |

| Community hospital | 68 (30.4) |

| Veterans Affairs hospital | 42 (18.8) |

| Comprehensive cancer center | 9 (4.0) |

| Otherc | 12 (5.4) |

| Total | 224 |

Abbreviation: RN, registered nurses.

Social work includes MSW and LCSW. Advanced practice nurse includes nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists.

Common write-in responses included physician assistants and Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing.

Common write-in responses included large city hospital and acute care facility.

Detecting and Managing Psychological Distress

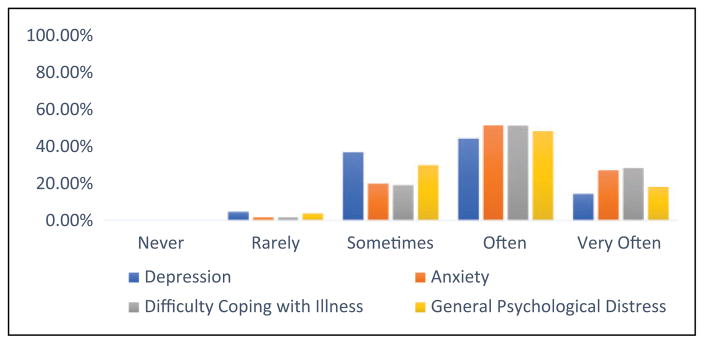

Figure 1 shows the frequency with which providers encounter various types of psychological distress in their practice. Overall, providers are encountering psychological distress frequently, and the most common types of distress are difficulty coping with illness and anxiety.

Figure 1.

Psychological distress frequency (n = 248).

All 224 (224/236 = 94.9%) participants answering this question, irrespective of discipline, reported that they use at least 1 method to screen patients for the presence of psychological distress. Providers reported using a variety of methods. The most frequent type of screening method was clinical interview, employed by 99.6% of providers, followed by talking to family members (92.4%), observing the patient’s mood (89.7%), reviewing medical records (74.6%), administering a formal screening instrument (34.4%), and having the patient evaluated by a mental health professional (11.2%). Clinicians reported using an average (standard deviation [SD]) of 4.01 (1.04) different types of screening methods to assess for psychological distress in their patients. Two hundred twenty-four clinicians responded to the question asking which types of formal screening measures they use. Participants were most likely to use the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (endorsed by 38.8% of participants), followed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (29.9%), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (19.2%), or some other screening measure (19.2%).

Participants responded that when they detect psychological distress in their patients, they refer these individuals to a number of different disciplines. Table 2 reflects which disciplines are receiving referrals most often. On average, participants reported referring to 3 different providers (SD = 1.46) when they identify psychological distress. When asked what participants do if they identify psychological distress, they endorsed an average of 4.3 (SD = 1.9) responses, which included referring to various providers, monitoring the patient themselves, starting a medication, or other response.

Table 2.

Referrals: When You Identify Psychological Distress, What Do You Do Next?a

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Within team approaches | |

| Refer to | |

| Social worker on the team | 164 (69.6) |

| Chaplain on the team | 156 (65.3) |

| Psychologist on the team | 60 (25.1) |

| Psychiatrist on the team | 26 (10.9) |

| Write-in: provide support myself | 23 (9.6) |

| Start an antidepressant | 133 (55.6) |

| Observe patient | 137 (57.3) |

| Strategies used external to the team | |

| Refer to | |

| Psychiatrist not on the team | 88 (36.8) |

| Support group | 73 (30.5) |

| Psychologist not on the team | 60 (25.1) |

| Chaplain not on the team | 48 (20.0) |

| Social worker not on the team | 37 (15.5) |

| Otherb | 51 (21.3) |

N = 239.

Most frequent other write-in responses included “provide support/counseling myself,” refer to rec, music or pet therapy, or community resources.

Managing Anxiety in Patients Receiving Palliative Care

All individuals (N = 236) responded to the question asking what nonpharmacological approaches they use to manage anxiety symptoms in patients receiving palliative care. Respondents endorsed an average of 3.6 (SD = 2.5) different types of non-pharmacological approaches to manage anxiety. Notably, 22.3% did not endorse using any nonpharmacological approaches, and these respondents were the same as those who indicated that they did not have access to nonpharmacological approaches to manage anxiety within their palliative care team. Table 3 reports the frequency of nonpharmacological approaches used to manage anxiety. The most frequently endorsed nonpharmacological approaches were general psychosocial support (68.2%), supportive counseling (68.2%), and spiritual support/counseling (54.7%).

Table 3.

What Nonpharmacological Techniques Do You Use to Manage Anxiety?a

| Type of Therapy | n (%) |

|---|---|

| General psychosocial support | 161 (68.2) |

| Supportive counseling | 161 (68.2) |

| Spiritual support/counseling | 129 (54.7) |

| Distraction techniques | 103 (43.6) |

| Relaxation training | 97 (41.1) |

| Mindfulness-based meditation exercises | 89 (37.7) |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques | 78 (33.1) |

| Otherb | 27 (11.4) |

N = 236.

Other approaches included write-in responses such as healing touch, massage, and art and music therapy.

Approximately 40% of respondents did not endorse using any empirically supported techniques (CBT, relaxation, mindfulness, and distraction) to manage anxiety symptoms, whereas 14% endorsed using 1, 12.3% endorsed using 2, 18.6% endorsed using 3, and 15.3% endorsed using all 4. An ANOVA revealed a significant effect of type of discipline and number of empirically supported treatments used (F2,16 = 7.39, P = .00). Tukey HSD and Bonferroni post hoc analyses both revealed that psychologists were significantly more likely than all other disciplines to use empirically supported techniques to manage anxiety at the P < .05 level (results not reported but are available by e-mail request). Finally, regarding pharmacological interventions, 84.6% of physicians and 54.5% of nurse practitioners reported that they prescribe anxiolytics or SSRIs when they detect psychological distress.

Discussion

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to ascertain actual clinical practices surrounding psychological distress screening and treatment in inpatient palliative care teams nationwide. The results from this study revealed that psychological distress is frequently encountered by palliative care teams and that there is a great deal of variability regarding how palliative care teams screen for and manage psychological distress.

The results reveal most palliative care team members, regardless of discipline, report assessing for psychological distress, and there is significant variability in how psychological distress is actually assessed. This study found that all core palliative care team members (ie, physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and psychologists), regardless of discipline, screen for psychological distress with at least 1 method, and on average, individuals screen with 4 different methods. The least frequent method of screening is using a validated screening instrument, and the most frequent is talking with family members. While it is likely advantageous to have multiple team members screen for psychological distress using multiple methods (eg, it may increase the likelihood of detecting psychological distress when present), it also potentially signals a lack of scientific evidence or at least guidelines for the most valid and reliable way to screen for psychological distress in the inpatient palliative care setting. The guidelines from the National Consensus Project and National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization state that the team provide “regular ongoing assessment of psychological reactions to the illness … and psychiatric conditions … whenever possible and appropriate, a validated and context-specific assessment tool is used.”8(p64) The Guidelines, however, do not give examples of which screening and assessment tools are best nor do they give detailed information about who on the team should perform this assessment and screening or what type of training is necessary for team members to be considered proficient at psychological screening and assessment. They also do not provide specific information on frequency of screening and assessment, rather they specify “regular reassessment of treatment efficacy … is performed and consistently documented.” Further research is needed to establish “best practices” and specific guidelines in screening for psychological distress in inpatient palliative care settings. Tools that are feasible for use (eg, can be conducted in a reasonable amount of time) and have acceptable sensitivity among patients with high symptom burden are particularly needed. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Tool is certainly context-specific and valid for assessing certain symptoms, but its validity for screening for psychological distress in palliative care settings has been questioned.11 The PHQ-9 has preliminary evidence as a suitable screening tool for depression in palliative care,21 but further research is needed to determine whether the measure is appropriate for monitoring response to treatment. There is also a need to develop screening tools that can differentiate between reactive sadness and clinically significant depression or anxiety, as current screening measures may be overdiagnosing depression in nondepressed adults.22

This study also revealed that palliative care team members refer patients to multiple disciplines to manage symptoms of anxiety. On average, respondents endorsed referring patients to 3 (SD = 1.46) different providers when symptoms of anxiety are detected. This suggests that the treatment of psychological distress is considered the purview of all disciplines rather than 1 discipline in particular. While all disciplines working in palliative care are expected to have some basic training and competency in managing psychological symptoms, there is an important distinction between providing psychological support generally to all patients versus providing psychological assessment and intervention for specific patients with clinically significant mental health needs. Our results suggest that when symptoms of anxiety are detected, any number of providers from a variety of disciplines may be consulted to help manage a patient’s psychological distress. It is possible that when a clinician believes that the psychological distress is related to a specific discipline’s expertise, the team member from that discipline receives the referral. For example, if a provider believes that the psychological distress is related to spiritual/religious/existential issues, chaplaincy may be more likely to receive the referral as opposed to social work or psychology. Our results could also suggest a lack of clarity in the guidelines and limited evidence regarding the best way to manage anxiety and other psychological symptoms in patients being seen by the palliative care team. The National Consensus Project Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care state that the “interdisciplinary team effectively treats psychiatric diagnoses … interventions are based on interdisciplinary team assessment and informed by evidence-based practice … “8(p22) These guidelines are quite general and leave much to the interpretation of palliative care teams. Furthermore, there is currently a gap in evidence-based practices in regard to managing psychological distress in palliative care.10 More research is needed to establish and disseminate to all relevant disciplines evidence-based interventions to treat psychological distress in palliative care. Additionally, future qualitative studies could help to illuminate why and when palliative care providers refer patients to various disciplines for psychological care. For example, certain palliative care teams may have social workers or chaplains who have specialized training in mental health interventions, which would make them especially well-suited to deliver psychological interventions to affected patients.

The results from the current study further demonstrate that providers from different disciplines treat symptoms of anxiety differently. The care a patient receives for their symptoms of anxiety and resulting care outcomes may well depend on which discipline receives or responds to the referral. For example, this study demonstrated that psychologists (vs other groups) are significantly more likely to employ psychotherapeutic techniques that have strong empirical support (eg, CBT, relaxation, and distraction). The overwhelming majority of physicians (and ~50% of nurse practitioners) reported using pharmacological agents such as anxiolytics or SSRIs to manage psychological distress. The most common types of nonpharmacological treatments offered were general psychosocial support, supportive counseling, and spiritual counseling. Although these types of support constitute important aspects of palliative care, they are not well operationalized and therefore make it difficult to study empirically or train clinicians systematically in their use. One review examined anxiety treatments for older adults and found that supportive therapy, which was operationalized as therapy that included reflective listening and validation of feelings, was less effective than CBT or relaxation training in managing anxiety symptoms.23 The delivery of spiritual counseling may be quite different across chaplains and across faith, and psychosocial support and supportive counseling do not have standard accepted definitions in the literature. For example, supportive counseling may include active listening for 1 provider, while for another it may mean therapeutic touch or empathic statements. Most importantly, without a clear understanding and definition of what these supportive therapies are, it is impossible to know whether they are effective in reducing psychological distress and symptoms of anxiety. Future research, such as qualitative interviews with palliative care providers, would be useful in order to better operationalize the types of supportive counseling, spiritual counseling, and psychosocial support currently being provided to patients as well as the rationale providers have for choosing different types of interventions for psychological symptoms.

If a patient is experiencing symptoms of anxiety, they may benefit from a psychological treatment with a robust evidence base supporting its efficacy such as CBT. Cognitive behavioral therapy has preliminary evidence supporting its efficacy in treating anxiety and depression in patients with advanced illness.24–26 This study found that CBT and CBT techniques are not routinely being offered to patients with symptoms of anxiety who are being managed by an inpatient palliative care team and that there is a great deal of variability in how symptoms of anxiety are currently being treated by palliative care providers. More research is needed on adapting CBT and other evidence-based psychotherapies to be more accessible (eg, improving funding/reimbursement mechanisms and increasing the number of available, trained providers) and appropriate (eg, reducing the number of sessions or making it more self-directed) for patients being treated by a palliative care team.

This study has several limitations to consider. Given the snowball sampling method utilized, we could not calculate a formal response rate. It is possible that selection bias influenced our results, for example, providers already doing some psychological screening and treatment in palliative care may have been more likely to respond than providers who do not routinely screen for and/or treat psychological distress. Additionally, it is possible that providers from the same team responded to the study, which would result in an overrepresentation from 1 particular hospital; however, we could not assess this due to anonymity requirements in the protocol. Sample representation also skewed toward urban academic medical centers, which may not reflect practices patterns in nonurban and nonacademic health systems. Rural palliative care teams were not equally represented in the sample (10.3%) and therefore may be a good target for future research, as rural palliative care teams may face unique challenges in providing psychological care. We were also unable to distinguish regional differences in practice patterns because we did not ask which geographic region participants were responding from. Lastly, because this was a self-report survey, respondents may have overestimated the extent to which they screen and manage psychological distress.

Lastly, this study focused on practice patterns regarding symptoms of psychological distress with a particular focus on management of anxiety. It is possible that respondents’ practice patterns regarding other psychological symptoms, such as depression or insomnia, could have been different. This study should not be generalized to reflect how all psychological distress is treated by palliative care teams, as survey items regarding treatment of psychological distress focused explicitly on symptoms of anxiety.

There is a great deal of variability in how palliative care teams screen for and manage psychological distress. This variability may be due, in part, to nonspecific guidelines for best practices and a limited evidence base regarding how best to manage psychological distress in palliative care settings. More research is needed to establish evidence-based screening and treatment practices for psychological distress in palliative care patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Rome RB, Luminais HH, Bourgeois DA, Blais CM. The role of palliative care at the end of life. [Accessed August 29, 2017];Ochsner J. 2011 11(4):348–352. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22190887. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham F, Clark D. WHO definition of palliative care. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;2(36):64–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fine RL. Depression, anxiety, and delirium in the terminally ill patient. [Accessed August 29, 2017];Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2001 14(2):130–133. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2001.11927747. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16369601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD. Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(6):1057–1064. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00430109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, et al. When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121(9):1513–1519. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bambauer KZ, Zhang B, Maciejewski PK, et al. Mutuality and specificity of mental disorders in advanced cancer patients and caregivers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(10):819–824. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0103-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care | NCHPC. [Accessed August 29, 2017];National consensus project for quality palliative care. 2013 http://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp-guidelines-2013/. Updated November 15, 2017.

- 9.Spetz J, Dudley N, Trupin L, Rogers M, Meier DE, Dumanovsky T. Few hospital palliative care programs meet national staffing recommendations. Health Aff. 2016;35(9):1690–1697. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozlov E, Niknejad B, Reid C. Palliative care gaps in providing psychological treatment: a review of the current state of research in multidisciplinary palliative care [published online January 1, 2017] Cancer. doi: 10.1177/1049909117723860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson LA, Jones GW. A review of the reliability and validity of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. Curr Oncol. 2009;16(1):53–64. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson M, MacGregor E, Sykes N, Hotopf M. The use of benzodiazepines in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2006;20(4):407–412. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1151oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller KE, Adams SM, Miller MM. Antidepressant medication use in palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2006;23(2):127–133. doi: 10.1177/104990910602300210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson K, Bennett K, Kenny RA. Polypharmacy including falls risk-increasing medications and subsequent falls in community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults. Age Ageing. 2015;44(1):90–96. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sylvestre M-P, Abrahamowicz M, Capek R, Tamblyn R. Assessing the cumulative effects of exposure to selected benzodiaze-pines on the risk of fall-related injuries in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(4):577–586. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Araujo KLB, Slattum P, Van Ness PH, Inouye SK. Benzodiazepine and opioid use and the duration of intensive care unit delirium in an older population. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(1):177–183. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318192fcf9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boland JW, Allgar V, Boland EG, et al. Effect of opioids and benzodiazepines on clinical outcomes in patients receiving palliative care: an exploratory analysis. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(11):1274–1279. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36(5):427–440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teachman B. Generalized anxiety disorder. Society of Clinical Psychology; [Accessed November 15, 2017]. https://www.div12.org/psychological-treatments/disorders/generalized-anxiety-disorder/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. [Accessed September 1, 2017];J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998 66(1):7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. http://www.div12.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Defining-Empirically-Supported-Therapies-1.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chilcot J, Rayner L, Lee W, et al. The factor structure of the PHQ-9 in palliative care. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(1):60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenzer J. Is the United States preventive services task force still a voice of caution? BMJ. 2017;356:j743. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayers CR, Sorrell JT, Thorp SR, Wetherell JL. Evidence-based psychological treatments for late-life anxiety. Psychol Aging. 2007;20(1):8–17. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G. Internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy for health problems: a systematic review. J Behav Med. 2008;31(2):169–177. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savard J, Simard S, Ivers H, Morin CM. Randomized study on the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia secondary to breast cancer, part I: sleep and psychological effects. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6083–6096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duarte PS, Miyazaki MC, Blay SL, Sesso R. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy is an effective treatment for major depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2009;76(4):414–421. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]