Abstract

This meta-analysis examines the association between teacher support and students' academic emotions [both positive academic emotions (PAEs) and negative academic emotions (NAEs)] and explores how student characteristics moderate these relationships. We identified 65 primary studies with 58,368 students. The results provided strong evidence linking teacher support and students' academic emotions. Furthermore, students' culture, age, and gender moderated these links. The correlation between teacher support and PAEs was stronger for Western European and American students than for East Asian students, while the correlation between teacher support and NAEs was stronger for East Asian students than for Western European and American students. Also, the correlation between teacher support and PAEs was strong among university students and weaker among middle school students, compared to other students. The correlation between teacher support and NAEs was stronger for middle school students and for female students, compared to other students.

Keywords: teacher support, academic emotions, meta-analysis, students, moderator analysis

Introduction

As students spend much of their time with their teachers in school, teacher support can be vital to students' academic development, including not only learning outcomes but also affective or emotional outcomes. Many empirical studies have shown that teacher support was significantly positively correlated with positive academic emotions (PAEs; e.g., enjoyment, interest, hope, pride, and relief) and significantly negatively correlated with negative academic emotions (NAEs; anxiety, depression, shame, anger, worry, boredom, and hopelessness), but their effect sizes vary substantially across studies (Skinner et al., 2008; Mitchell and DellaMattera, 2011; King et al., 2012; McMahon et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2016). Hence, there is a need for a systematic integration of the results of these studies to better understand the relation between teacher support and students' academic emotions and attributes that moderate this relation. This meta-analysis addresses this issue by examining 65 primary studies with 58,368 students. We begin by defining the two central notions: teacher support and academic emotions.

Teacher support

Self-determination and social support offer two definitions for teacher support. The self-determination view suggests that teacher support occurs when students perceive cognitive (Skinner et al., 2008), emotional (Skinner and Belmont, 1993), or autonomy-oriented support from a teacher during the students' learning process (Wellborn and Connell, 1987). According to Ryan and Deci (2000), individuals do work and complete tasks based on their values, interests, and hobbies, but others close to them can influence their related emotions and motivations. Teacher support includes three dimensions: support for autonomy, structure, and involvement. Support for autonomy is teacher provision of choice, relevance, or respect to students. Structure is clarity of expectations and contingencies. Involvement is warmth, affection, dedication of resources, understanding the student, or dependability (Skinner et al., 2008). Research applying this definition of teacher support has found that it can influence anxiety, depression, hope, and other emotions among students (Reddy et al., 2003; Skinner et al., 2008; Van Ryzin et al., 2009).

In the social support model, teacher support can be viewed in two ways: broad or narrow. The broad perspective, based on Tardy's (1985) social support framework, defines teacher support as a teacher giving informational, instrumental, emotional, or appraisal support to a student, in any environment (Tardy, 1985; Kerres Malecki and Kilpatrick Demary, 2002). Informational support is giving advice or information in a particular content area. Instrumental support is giving resources such as money or time. Emotional support is love, trust, or empathy. Appraisal support is giving evaluative feedback to each student (Malecki and Elliott, 1999). The narrow perspective views teacher support in the form of help, trust, friendship, and interest only in a classroom environment (Fraser, 1998; Aldridge et al., 1999).

Teacher support enhances a teacher's relationship with a student. Specifically, teachers who support students show their care and concern for their students, so these students often reciprocate this concern and respect for the teacher by adhering to classroom norms (Chiu and Chow, 2011; Longobardi et al., 2016). When teachers shout at students, blame them, or aggressively discipline them, these students often show less concern for their teachers and fewer cooperative classroom behaviors (Miller et al., 2000).

As might be expected from this variation and diffuseness in definitions of teacher support, none of them specify a direct relationship between teacher support and students' academic emotions, making it difficult to determine the salient levers for intervention and support. Therefore, we conduct a meta-analysis to integrate these diverse frameworks and streamline the knowledge base, thereby promoting the development of this field.

Academic emotions

Academic emotions refer to the emotional experience of learning (and teaching), including enjoyment, hopelessness, boredom, anxiety, and anger (Pekrun et al., 2002), which can affect students' learning outcomes (Dong and Yu, 2007). Researchers have generally divided academic emotions into two categories: positive academic emotions (PAEs) and negative academic emotions (NAEs); however, they disagree about how to delineate their boundaries. According to Pekrun et al. (2002), PAEs include relief, hope, enjoyment, and pride, while NAEs include shame, anxiety, boredom, anger, and hopelessness. Other researchers also include calmness and contentment in PAEs or depression and fatigue in NAEs (Dong and Yu, 2007; Sorić, 2007). PAEs may also include excitement, happiness, and other indicators (Dong and Yu, 2007), while NAEs may include sense of threat, fear, and others (Dong and Yu, 2007). Based on the literature, the current study define PAEs as including interest, hope, enjoyment, pride, calmness, contentment, and relief; and NAEs as including shame, anxiety, anger, worry, boredom, depression, fatigue, and hopelessness. For a fuller picture, the measurement of academic emotions should include both PAEs and NAEs.

The relationship between teacher support and students' academic emotions

Many empirical studies have shown that students with more teacher support have higher PAEs or lower NAEs. Specifically, students with more teacher support have more enjoyment, interest, hope, pride, or relief (PAEs); or less anxiety, depression, shame, anger, worry, boredom, or hopelessness (NAEs) (Ahmed et al., 2010; King et al., 2012; Tian et al., 2013). As the effect sizes differ substantially among these studies (Skinner et al., 2008; King et al., 2012; McMahon et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2016), later studies tried to summarize the earlier results (e.g., Weber et al., 2001; Clark, 2008; Arbeau et al., 2010; Lazarides and Ittel, 2013). However, these studies only partly verified the underlying phenomena, as some studies had limitations such as convenience sampling or ignoring sample size –resulting in low reliability and reducing the quality of the research. Therefore, to determine clearly the link between teacher support and students' academic emotions, a meta-analysis is needed.

Through a review of past empirical research on teacher support and students' academic emotions, we found that many effect sizes were heterogeneous, suggesting that moderators might account for these differences. Specifically, we examined the potential moderating roles of students' cultures, ages, and genders.

Potential moderators of the link between teacher support and students' academic emotions

Culture

Several studies have implied that culture may influence the association between teacher support and students' academic emotions. For example, Karagiannidis et al. (2015) study of students from Greece showed a strong correlation between teacher support and PAE indicators but only a weak correlation between teacher support and NAE indicators. In contrast, King et al.'s (2012) study of students from Philippines, found a weak correlation between teacher support and PAE indicators but a strong one between teacher support and NAE indicators.

Age

The link between teacher support and students' academic emotions might differ by the latter's (Klem and Connell, 2004; Frenzel et al., 2007). For example, past studies found that the relation between teacher support and indicators of PAE was lowest among middle school students and highest among university students, relative to elementary and high school students (Aldridge et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2016). Meanwhile the link between teacher support and indicators of NAE was strongest for middle school students (Taylor, 2003; Huang et al., 2010; Martínez et al., 2011). According to these findings, we expect age to moderate the relation between teacher support and students' academic emotions.

Gender

Female students tend to receive more teacher support than do male students (Lutz, 1996; Baumeister and Sommer, 1997), and several empirical studies have shown gender differences in the link between teacher support and indicators of students' academic emotions, such as interest, depression, anxiety (Van Ryzin et al., 2009; Sylva et al., 2012; Nilsen et al., 2013). According to these findings, we expect gender to moderate the correlation between teacher support and students' academic emotions.

Study purpose

This meta-analysis of 65 studies analyzed the relations between teacher support and students' academic emotions (positive and negative) and their moderators. Specifically, this study examined: (a) the correlations between teacher support and students' positive academic emotions, (b) the correlations between teacher support and students' positive academic emotions, and (c) whether culture, age, or gender moderated these correlations.

Methods

Literature search

To locate studies on teacher support and students' academic emotions, we systematically searched the literature from January 1994 (Through search in above-mentioned database, “the relationship between teacher support and students' academic emotions” was firstly proposed by Karabenick and Sharma, 1994) to January 2016 using the following electronic databases: ProQuest Dissertations, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Springer, Taylor & Francis, EBSCO, PsycINFO, and Elsevier SDOL. Indexed keywords constituted terms reflecting teacher support (support, involvement, care/caring, warmth, closeness, teacher enthusiasm, teacher help, learning environment, classroom environment, social support, relationship between teacher and student/child) and academic emotions (anxiety, pride, shame, achievement emotion, interest, anger, depression, enjoyment, boredom, hope, worry, hopelessness, positive affect, academic emotions, negative affect, relief, well-being). We obtained full-text versions of articles from libraries when they could not be found online, limiting ourselves to articles written in English. We used inclusion and exclusion criteria described in the next subsections to analyze and filter the collected studies.

Literature exclusion criteria

We included articles based on the following criteria: (a) studying the relationship between teacher support and students' academic emotions, (b) measuring teacher support, including any of the keywords mentioned above, (c) measuring academic emotions, again including any of those above keywords, (d) including an explicit sample size, and (e) explicitly reporting the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (r) or a t or F value that could be transformed into r. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 65 articles remained.

Coding

To facilitate meta-analysis, feature coding was conducted on 65 articles. We considered the following variables: author(s) and publication year, proportion of male students, ages, indicators of teacher support, indicators of academic emotions, types of academic emotions (PAEs and NAEs), number of students, and r effect size. The following criteria guided the coding procedure (see Table 1): (a) effect sizes of each independent sample were coded based on an independent sample, and separately coded if a study had several independent samples; (b) correlations between different indicators of teacher support and academic emotions were separately coded; (c) correlations between teacher support and different indicators of academic emotions were separately coded; (d) this number was used if an independent sample provided effect sizes (expressed as r) for sample characteristics such as sex; and (e) if a study reported multiple correlations between teacher support and an academic emotion, their mean value was used.

Table 1.

Studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author (year) | N | r | TS indicatora | AE indicatorb | AE type | Culturec | Aged | Male (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afari, 2013 | 352 | 0.24 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 1 | 4 | 0.34 |

| Ahmed et al., 2010 | 238 | 0.28 | TS | Interest | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.46 |

| Ahmed et al., 2010 | 238 | 0.45 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.46 |

| Ahmed et al., 2010 | 238 | −0.21 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.46 |

| Aldridge et al., 2013 | 352 | 0.24 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 3 | 4 | 0.656 |

| Allen and Fraser, 2007 | 520 | 0.21 | TS(p) | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Allen and Fraser, 2007 | 520 | 0.01 | TS(s) | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Arbeau et al., 2010 | 169 | −0.26 | C | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.499 |

| Arslan, 2009 | 466 | −0.21 | TS | Anger | NAEs | 3 | 3 | 0.457 |

| Birgani et al., 2015 | 180 | 0.36 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Burić, 2015 | 365 | 0.27 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 3 | 3 | 0.356 |

| Burić, 2015 | 365 | 0.22 | TS | Hope | PAEs | 3 | 3 | 0.356 |

| Burić, 2015 | 365 | 0.19 | TS | Pride | PAEs | 3 | 3 | 0.356 |

| Burić, 2015 | 365 | 0.15 | TS | Relief | PAEs | 3 | 3 | 0.356 |

| Burić, 2015 | 365 | −0.17 | TS | Anger | NAEs | 3 | 3 | 0.356 |

| Burić, 2015 | 365 | −0.06 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 3 | 3 | 0.356 |

| Burić, 2015 | 365 | −0.09 | TS | Shame | NAEs | 3 | 3 | 0.356 |

| Burić, 2015 | 365 | −0.06 | TS | Hopelessness | NAEs | 3 | 3 | 0.356 |

| Cheung, 1995 | 128 | −0.28 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 1 | 5 | 0.475 |

| Chirkov and Ryan, 2001 | 116 | −0.14 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 3 | 0.422 |

| Chirkov and Ryan, 2001 | 120 | 0.08 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.358 |

| Chirkov and Ryan, 2001 | 119 | 0.22 | TS | Positively emotions | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.532 |

| Chirkov and Ryan, 2001 | 118 | −0.03 | TS | Negatively emotions | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.532 |

| Cox et al., 2009 | 411 | 0.45 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.436 |

| Cox et al., 2009 | 411 | −0.16 | TS | Worry | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.436 |

| Demaray et al., 2005 | 82 | −0.04 | TS | Emotional symptoms | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.354 |

| Elmelid et al., 2015 | 643 | −0.05 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.455 |

| Elmelid et al., 2015 | 643 | 0.17 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.455 |

| Elmelid et al., 2015 | 643 | −0.06 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.455 |

| Elmelid et al., 2015 | 643 | 0.2 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.455 |

| Federici and Skaalvik, 2014 | 309 | −0.14 | ES | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.482 |

| Federici and Skaalvik, 2014 | 309 | −0.13 | IS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.482 |

| Frenzel et al., 2009 | 1,542 | 0.48 | TE | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.48 |

| Gläser-Zikuda and Fuß, 2008 | 431 | −0.26 | TC | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.494 |

| Hagenauer and Hascher, 2010 | 356 | 0.51 | TC | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.336 |

| Hill et al., 1996 | 87 | −0.27 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.471 |

| Huang et al., 2010 | 158 | −0.26 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 1 | 4 | 0.684 |

| Jia et al., 2009 | 706 | −0.27 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.495 |

| Jia et al., 2009 | 709 | −0.25 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.482 |

| Karabenick and Sharma, 1994 | 288 | −0.11 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 4 | 0.36 |

| Karabenick and Sharma, 1994 | 288 | −0.17 | TS | Negatively affect | NAEs | 2 | 4 | 0.36 |

| Karagiannidis et al., 2015 | 627 | 0.47 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.499 |

| Karagiannidis et al., 2015 | 627 | −0.29 | TS | Boredom | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.499 |

| King et al., 2012 | 1,147 | 0.15 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.542 |

| King et al., 2012 | 1,147 | 0.12 | TS | Hope | PAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.542 |

| King et al., 2012 | 1,147 | 0.07 | TS | Pride | PAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.542 |

| King et al., 2012 | 1,147 | −0.4 | TS | Anger | NAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.542 |

| King et al., 2012 | 1,147 | −0.18 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.542 |

| King et al., 2012 | 1,147 | −0.23 | TS | Shame | NAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.542 |

| King et al., 2012 | 1,147 | −0.47 | TS | Boredom | NAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.542 |

| King et al., 2012 | 1,147 | −0.33 | TS | Hopelessness | PAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.542 |

| Lapointe et al., 2005 | 593 | −0.11 | TH | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.496 |

| LaRusso et al., 2008 | 476 | −0.2 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 3 | N |

| Lazarides and Ittel, 2013 | 212 | 0.47 | TS | Interest | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Lazarides and Ittel, 2013 | 149 | 0.42 | TS | Interest | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Liu et al., 2016 | 873 | 0.45 | TS | Affect in school | PAEs | 1 | 1 | N |

| Liu et al., 2016 | 675 | 0.35 | TS | Affect in school | PAEs | 1 | 2 | N |

| Liu et al., 2016 | 610 | 0.33 | TS | Affect in school | PAEs | 1 | 3 | N |

| Ludwig and Warren, 2009 | 175 | 0.43 | TS | Hope | PAEs | 2 | 3 | 0.486 |

| MacPhail, 2012 | 125 | 0.25 | TS | Positively affect | PAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.472 |

| MacPhail, 2012 | 125 | −0.18 | TS | Negatively affect | NAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.472 |

| Martínez et al., 2011 | 140 | −0.27 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 3 | 2 | 0.429 |

| Martínez et al., 2011 | 140 | −0.44 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 3 | 1 | 0.429 |

| McMahon et al., 2013 | 188 | 0.02 | TS | Fear | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.37 |

| McMahon et al., 2013 | 188 | 0.09 | TS | Worry | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.37 |

| McMahon et al., 2013 | 188 | −0.02 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.37 |

| McMahon et al., 2013 | 188 | −0.18 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.37 |

| Murberg and Bru, 2009 | 198 | −0.19 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 3 | 0.439 |

| Myint and Fisher, 2001 | 1,188 | 0.31 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 1 | 2 | 0.457 |

| Neville, 2008 | 159 | 0.27 | TS | Positively affect | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.47 |

| Neville, 2008 | 159 | −0.13 | TS | Negatively affect | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.47 |

| Nilsen et al., 2013 | 319 | −0.09 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.404 |

| Nilsen et al., 2013 | 319 | −0.2 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.404 |

| Ommundsen and Kvalø, 2007 | 194 | 0.63 | TS | Enjoyment/Interest | PAEs | 2 | 3 | 0.515 |

| Ommundsen et al., 2006 | 760 | 0.11 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.499 |

| Pan, 2014 | 462 | 0.59 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 1 | 3 | 0.561 |

| Piechurska-Kuciel, 2011 | 354 | −0.78 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.362 |

| Reddy et al., 2003 | 1,285 | −0.28 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Reddy et al., 2003 | 1,300 | −0.25 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Rey et al., 2007 | 89 | −0.07 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.472 |

| Rueger et al., 2008 | 108 | −0.25 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Rueger et al., 2008 | 108 | −0.29 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Rueger et al., 2008 | 138 | −0.06 | TS | Anxious | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Rueger et al., 2008 | 138 | −0.23 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Ryan et al., 2005 | 474 | 0.4 | TS | Positively affect | PAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Ryan et al., 2005 | 474 | −0.15 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Sahaghi et al., 2015 | 180 | 0.37 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Sakiz, 2012 | 227 | 0.64 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 3 | 4 | 0.374 |

| Sakiz, 2012 | 227 | −0.55 | TS | Hopelessness | NAEs | 3 | 4 | 0.374 |

| Sakiz, 2012 | 138 | 0.6 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 3 | 1 | 0.514 |

| Sakiz, 2012 | 138 | −0.21 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 3 | 1 | 0.514 |

| Sakiz et al., 2012 | 317 | 0.62 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Sakiz et al., 2012 | 317 | −0.41 | TS | Hopelessness | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Sakiz et al., 2007 | 99 | 0.67 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.343 |

| Sakiz et al., 2007 | 99 | −0.36 | TS | Hopelessness | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.343 |

| Skinner et al., 2008 | 805 | −0.1 | TS(t) | Bored | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.488 |

| Skinner et al., 2008 | 805 | −0.12 | TS(t) | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.488 |

| Skinner et al., 2008 | 805 | −0.1 | TS(t) | Frustrated | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.488 |

| Skinner et al., 2008 | 805 | −0.56 | TS(s) | Bored | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.488 |

| Skinner et al., 2008 | 805 | −0.36 | TS(s) | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.488 |

| Skinner et al., 2008 | 805 | −0.38 | TS(s) | Frustrated | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.488 |

| Sun and Hui, 2007 | 680 | −0.28 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Sun and Hui, 2007 | 678 | −0.27 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Sun et al., 2006 | 433 | −0.26 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 1 | 5 | 0.552 |

| Sylva et al., 2012 | 1,766 | 0.53 | TS | Enjoyment | PAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.481 |

| Sylva et al., 2012 | 1,766 | −0.13 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 5 | 0.481 |

| Tanigawa et al., 2011 | 239 | −0.37 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Tanigawa et al., 2011 | 305 | −0.36 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Taylor and Fraser, 2003 | 745 | −0.04 | TS | Anxiety | NAEs | 2 | 3 | N |

| Telan, 2000 | 694 | −0.07 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 1 | 0.487 |

| Tian et al., 2013 | 361 | 0.42 | TS | Positively emotions | PAEs | 1 | 5 | 0.468 |

| Tian et al., 2013 | 361 | −0.31 | TS | Negatively emotions | NAEs | 1 | 5 | 0.468 |

| Van Ryzin, 2011 | 423 | 0.25 | TS | Hope | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.533 |

| Van Ryzin et al., 2009 | 231 | 0.22 | TS | Hope | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.524 |

| Wang, 2009 | 1,042 | −0.09 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.48 |

| Wang and Eccles, 2013 | 1,157 | 0.24 | TS | Positively emotions | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.48 |

| Way et al., 2007 | 1,451 | −0.26 | TS | Depression | NAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.458 |

| Weber et al., 2001 | 46 | 0.14 | TS | Affect | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.522 |

| Weber et al., 2001 | 46 | 0.12 | TS | Affect | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.522 |

| Wentzel, 1998 | 167 | 0.39 | TS | Interest | PAEs | 2 | 2 | 0.509 |

| Yang et al., 2015 | 472 | 0.53 | TS | Positively motions | PAEs | 1 | 1 | 0.663 |

TS, teacher support; TC, teacher's care; TE, teacher enthusiasm; ET, emotions support; IS, instrumental support; C, closeness; TH, teacher help; (p), parents report; (t), teacher report; (s), students self-report, Others were students self-report.

AE, Academic emotions.

1, East Asia; 2, Western European/American; 3, other.

1, Elementary; 2, Middle School; 3, High School; 4, University; 5, Mixed.

N, Not report.

When coding was complete, effect sizes between teacher support and students' academic emotions were calculated for each sample, based on the principles of meta-analysis (Lipsey and Wilson, 2001). The moderators tested for influence on the association between teacher support and students' academic emotions were (a) culture, (b) age, and (c) gender.

Culture was coded as “East Asia,” “Western European/American,” or “other”; “East Asia” referred to students from Asian countries such as China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan), South Korea, the Philippines, Singapore, and so on. “Western European/American” referred to students from European and North American countries such as Germany, the United States of America, and so on. “Other” referred to students from Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Iran, and so on. Age was coded as “elementary,” “middle school,” “high school,” “university,” and “mixed.” “Mixed” denoted that the participants in a study included at least two categories of the above school categories. Gender was coded as the proportion of male students.

Data analysis

We used the comprehensive meta-analysis software CMA 2.0 to analyze all the data. A fixed-effects model calculated the homogeneity and mean effects. Averaged weighted correlation coefficients (within- and between- inverse-variance weights) of independent samples were used to compute mean effect sizes. Moderators were identified by the homogeneity test, which revealed variance in effect sizes between different samples' characteristics. Where the homogeneity test was significant (QBet > 0.05), post-hoc analysis confirmed the different groups statistically. For continuous variables, this study used meta-analysis to examine variation in effect sizes explained by the moderator.

Results

Correlation between teacher support and academic emotions

After filtering the literature, we used 65 independent samples, and the sizes of 121 effects were calculated (45 effect sizes between teacher support and PAEs, 76 between teacher support and NAEs). In all, 58,368 students participated in the studies reviewed; sample sizes of individual studies ranged from 46 to 1,766.

To test our hypotheses, we calculated sample sizes (k), weighted effect sizes (r), and 95% confidence intervals (see Table 2). A fixed effects model was used to homogenize the analysis. The results showed that students with more teacher support had higher PAEs [r = 0.340 (z = 51.909, p < 0.001, k = 45, 95% CI = 0.328, 0.351)] or lower NAEs [r = −0.215 (z = −41.769, p < 0.001, k = 76, 95% CI = −0.225, −0.206)]. These effect sizes were suitable for moderator analysis (Cohen, 1969).

Table 2.

Fixed model of correlations between teacher support and academic emotions.

| k | N | Mean r | 95% CI for r | Homogeneity test | Tau-squared | Test of null (two-tailed) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | Q(r) | p | I-squared | Tau-squared | SE | Tau | z-value | ||||

| PAEs | 45 | 21690 | 0.340 | 0.328 | 0.351 | 823.197 | 0.00 | 94.655 | 0.038 | 0.011 | 0.194 | 51.909*** |

| NAEs | 76 | 36678 | −0.215 | −0.225 | −0.206 | 1218.358 | 0.00 | 93.844 | 0.032 | 0.007 | 0.179 | −41.769*** |

p < 0.001.

Moderator analysis

To test the aforementioned factors moderating the relationship between teacher support and students' academic emotions, we conducted two total homogeneity tests across 45 and 76 independent samples for PAEs and NAEs respectively. The results showed significant homogeneity coefficients between teacher support and academic emotions (QT(44)PAE = 823.197, p < 0.001; QT(75)NAE = 1218.358, p < 0.001). This indicates that culture, age, and gender moderated the relations between teacher support and students' PAEs and NAEs. We used meta-analysis of variance to confirm whether culture and age moderated the correlations between teacher support and academic emotions, and used meta-regression analyses to examine whether gender influenced these correlations.

Culture

As indicated in Table 3, the homogeneity test showed a significant homogeneity coefficient between teacher support and PAEs across our three cultures (East Asian, Western European/American, and other) (QBET = 60.599, df = 2, p < 0.001). As the table shows, the Western European/American group had a stronger correlation (r = 0.384, 95% CI = 0.368, 0.400) than the East Asian group (r = 0.286, 95% CI = 0.266, 0.305). Likewise, the homogeneity test found significant differences in the correlation between teacher support and NAEs across the three cultures (QBET = 119.523, df = 2, p < 0.001); however, in this case, the East Asian group (r = −0.307, 95% CI = −0.326, −0.288) showed a stronger correlation between teacher support and NAEs than the West European/American group (r = −0.190, 95% CI = −0.202, −0.178).

Table 3.

Culture and age as moderators of the association between teacher support and academic emotions.

| Between-group effect (QBET) | k | N | Mean r | SE | 95% CI for r | Homogeneity test within each group (QW) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||||

| PAEs | ||||||||

| Culture | 60.599*** | |||||||

| East Asian | 11 | 8434 | 0.286 | 0.017 | 0.266 | 0.305 | 270.216*** | |

| Western European/American | 26 | 11071 | 0.384 | 0.016 | 0.368 | 0.400 | 409.543*** | |

| Other | 8 | 2185 | 0.315 | 0.025 | 0.276 | 0.352 | 82.839*** | |

| Age | 42.450*** | |||||||

| Elementary | 7 | 3122 | 0.348 | 0.034 | 0.316 | 0.378 | 133.060*** | |

| Middle school | 23 | 11841 | 0.310 | 0.014 | 0.294 | 0.327 | 378.373*** | |

| High school | 10 | 3261 | 0.350 | 0.020 | 0.319 | 0.379 | 111.512*** | |

| University | 2 | 579 | 0.415 | 0.186 | 0.346 | 0.481 | 10.586*** | |

| Mixed | 3 | 2887 | 0.419 | 0.085 | 0.388 | 0.449 | 121.869*** | |

| NAEs | ||||||||

| Culture | 119.523*** | |||||||

| East Asian | 12 | 8879 | −0.307 | 0.005 | −0.326 | −0.288 | 89.629*** | |

| Western European/American | 54 | 24876 | −0.190 | 0.009 | −0.202 | −0.178 | 879.848*** | |

| Other | 10 | 2923 | −0.145 | 025 | −0.181 | −0.109 | 129.358*** | |

| Age | 164.830*** | |||||||

| Elementary | 8 | 1916 | −0.160 | 0.010 | −0.204 | −0.116 | 23.240* | |

| Middle school | 34 | 18929 | −0.276 | 0.007 | −0.289 | −0.262 | 435.489*** | |

| High school | 9 | 3461 | −0.120 | 0.003 | −0.152 | −0.086 | 16.424* | |

| University | 5 | 1313 | −0.135 | 0.075 | −0.187 | −0.081 | 105.465*** | |

| Mixed | 20 | 11059 | −0.158 | 0.018 | −176 | −0.140 | 95.982**** | |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.001.

Age

The results of the homogeneity test (QBET = 42.450, df = 4, p < 0.001) suggested that age influenced the link between teacher support and PAEs. Teacher support was significantly correlated with PAEs for elementary school (r = 0.348, 95% CI = 0.316, 0.378), middle school (r = 0.310, 95% CI = 0.294, 0.327), high school (r = 0.350, 95% CI = 0.319, 0.379), and university (r = 0.415, 95% CI = 0.346, 0.481); however, undergraduates showed a stronger correlation than the other students, and middle school students showed a weaker correlation than the other students. As shown in Table 3, the homogeneity test (QBET = 164.830, df = 4, p < 0.001) suggested that age moderated the link between teacher support and NAEs. Broken down by age group, significant correlations were observed between teacher support and NAEs for elementary students (r = −0.160, 95% CI = −0.204, −0.116), middle school students (r = −0.276, 95% CI = −0.289, −0.262), high school students (r = −0.120, 95% CI = −0.120, −0.086), and undergraduates (r = −0.135, 95% CI = −0.187, −0.081). The results indicated that middle school students had a stronger correlation between teacher support and NAEs than the other three groups.

Gender

To examine whether gender moderated the link between teacher support and students' academic emotions, r was meta-regressed onto the percentage of male students in each sample. As seen in Table 4, the meta-regression analysis (QModel[1, k = 40]PAE = 0.781, p > 0.05) suggested that gender did not moderate the relationship between teacher support and PAEs. However, meta-regression (QModel[1, k = 72]NAE = 4.208, p < 0.05) demonstrated that the relation between teacher support and NAEs was moderated by gender; the effect size of the correlation between teacher support and NAEs for an all-female sample (r = −0.252) was much stronger than for an all-male sample (r = −0.196).

Table 4.

Meta-regression analyses of gender.

| Variable | Parameter | Estimate | SE | z-value | 95% CI for b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||||

| PAEs | Male (%) | β0 | 0.375 | 0.031 | 11.961 | 0.314 | 0.436 |

| β1 | −0.055 | 0.062 | −0.884 | −0.176 | −0.066 | ||

| Q Model(1, k = 40) = 0.781, p > 0.05 | |||||||

| NAEs | Male (%) | β0 | −0.196 | 0.014 | −13.859 | −0.224 | −0.168 |

| β1 | 0.056 | 0.027 | −2.051 | −0.110 | −0.002 | ||

| Q Model(1, k = 72) = 4.208, p < 0.05 | |||||||

Publication bias

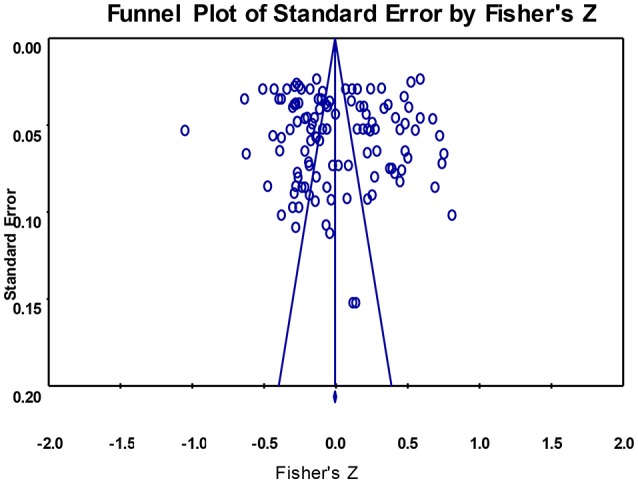

To examine whether the results were biased due to the effect sizes from various sources, a funnel plot was drawn (see Figure 1); it indicated that the 121 effects were symmetrically distributed on both sides of the average in terms of size. Egger's regression (Egger et al., 1997), an effective method for examining publication bias (Teng et al., 2015), revealed no significant bias [t(119) = 0.698, p = 0.486]. In addition, we also twice conducted Egger's regression analysis on teacher support, for PAEs and for NAEs. The results showed no publication bias [tPAE(43) = 0.800, p = 0.428; tNAE(74) = 0.453, p = 0.652]. This indicates that the overall correlation between teacher support and students' academic emotions was stable.

Figure 1.

Funnel plot of effect sizes of the correlation between teacher support and academic emotions.

Discussion

In the current meta-analysis 65 recent studies, including 121 effects and 58,368 students, were analyzed. The overall results showed that teacher support was positively correlated with PAEs and negatively correlated with NAEs; the correlation coefficients for these results were both medium. Furthermore, culture, age, and gender moderated these relations.

The significant correlation between teacher support and students' academic emotions

Meta-analysis results showed a significant positive correlation between teacher support and PAEs and a significant negative correlation between teacher support and NAEs. These results suggest that teacher support is an important mechanism through which teacher can foster students' PAEs and reduce their NAEs (Lawman and Wilson, 2013). These results support a direct effect model, and future studies can test an indirect effect model.

Furthermore, students with difficult learning problems or other problems can seek teacher support as a strategy to improve their PAEs and reduce their NAEs. Furthermore, teacher support is readily accessible on school days and can supplement a student's other interpersonal relationships, especially if the latter are unreliable. In addition, targeted interventions can help students facing difficulties seek out and capitalize on teacher support to improve their learning outcomes.

Moderation effects

The results also showed that students' culture, age, and gender moderated the relationship between teacher support and students' academic emotions. Specifically, culture and student age moderated teacher support's links with both PAEs and NAEs, and gender moderated teacher support's links with NAEs.

Moderating role of culture

Culture moderated the link between teacher support and students' academic emotions, consistent with many prior studies (Jia et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2016). This result suggests that training and interventions should consider cultural aspects, especially cultural differences when adapting training to a new culture. Specifically, the current study obtains the interesting finding that the Western group showed a stronger correlation between

As teacher support had a stronger positive correlation to PAEs among the Western European/American students than the East Asian students, teachers might have a larger impact on enhancing the PAEs of Western European/American students than those of East Asian students. In contrast, teacher support had a stronger negative correlation to NAEs among East Asian students than among Western European/American students, suggesting that teachers might have a larger impact on reducing the NAEs of East Asian students than those of Western European/American students. Future research can examine the mechanisms for these cultural differences.

Moderating role of age

Age moderates the relationship between teacher support and students' academic emotions, consistent with past studies (Martínez et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2016). Further analysis found that the middle school group showed a weaker correlation between teacher support and PAEs and a stronger correlation between teacher support and NAEs than other groups, while the university group obtained a stronger correlation between teacher support and PAEs than other groups. Middle school students are in a psychological weaning period (Huizhen, 2014), and teachers can have a large impact on such vulnerable students with large NAEs. However, their low baseline hinders teachers from sharply increasing their PAEs.

Moderating role of gender

Gender moderates the relationship between teacher support and NAEs, with a stronger correlation among female students than among male students; in contrast, gender did not moderate the link between teacher support and PAEs. As the emotional understanding and social skills of females often exceed those of males, female students might express their NAEs to their teachers more effectively than male students do, enabling their teacher support to reduce female students' NAEs more than male students' NAEs. In addition, this finding suggests that similar levels of teacher support may lead to lower NAEs among female than among male students. Considering both age and gender differences in the correlation between teacher support and NAEs, middle school boys emerge as the most vulnerable group, so targeting interventions for them might be especially fruitful.

Limitations and implications

The current meta-analysis has several limitations. First, only teacher support, involvement, care/caring, warmth, closeness, enthusiasm, and help were selected as indicators of teacher support; other indicators, such as concern, were excluded. Furthermore, the selected indicators may overlap. Second, parallel concerns also apply to indicators of academic emotions. Third, all the studies reviewed examined only direct effects; other studies have found that teacher support can indirectly affects students' academic emotions across other variables as well (Van Ryzin et al., 2009; Sakiz et al., 2012). Therefore, future studies can test for indirect effects, such as whether teacher support indirectly improves academic achievement via academic emotions. Fourth, the current study only considers whether students' culture, age, and gender moderate the relationship between teacher support and students' academic emotions; other variables, such as socio-economic status, can be examined in future studies. Fifth, this study included only English-language articles; future meta-analyses can include studies in other lanugages. Sixth, this meta-analysis was based on cross-sectional studies, so causal relationships cannot be inferred.

Conclusion

The results of this meta-analysis of 65 studies encompassing 121 effect sizes and 58,368 students revealed that teacher support was significantly correlated with students' academic emotions, and that these relations were moderated by culture, age, and gender. The positive link between teacher support and PAEs was stronger among Western European/American students than among East Asian students. In contrast, the negative link between teacher support and NAEs was stronger among East Asian students than among Western European/American students. The positive link between teacher support and PAEs was strongest among university students and weakest among middle school students. Also, the negative link between teacher support and NAEs was strongest among middle school students and among females.

Author contributions

HL provided the idea, designed this study and wrote the manuscript, contributed to data collection. YC provided the idea, designed this study and wrote the manuscript, contributed to data analysis. MC contributed to design this study, analysis data and revise paper. All authors approval of the version to be published and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

*References marked with asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

Funding. This research was supported by the Philosophy and Social Sciences Major—Breakthrough Project of the Ministry of Education in China (16JZD047), and the summit—education program of East China Normal University.

References

- *Afari E. (2013). The Effects of Psychosocial Learning Environment on Students' Attitudes Towards Mathematics. Rotterdam: Application of Structural Equation Modeling in Educational Research and Practice Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- *Ahmed W., Minnaert A., van der Werf G., Kuyper H. (2010). Perceived social support and early adolescents' achievement: the mediational roles of motivational beliefs and emotions. J. Youth Adolesc. 39, 36–46. 10.1007/s10964-008-9367-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Aldridge J. M., Afari E., Fraser B. J. (2013). Influence of teacher support and personal relevance on academic self-efficacy and enjoyment of mathematics lessons: a structural equation modeling approach. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 58, 614–633. 10.1037/t38960-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge J. M., Fraser B. J., Huang T.-C. I. (1999). Investigating classroom environments in Taiwan and Australia with multiple research methods. J. Educ. Res. 93, 48–62. 10.1080/00220679909597628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Allen D., Fraser B. J. (2007). Parent and student perceptions of classroom learning environment and its association with student outcomes. Learn. Environ. Res. 10, 67–82. 10.1007/s10984-007-9018-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Arbeau K. A., Coplan R. J., Weeks M. (2010). Shyness, teacher–child relationships, and socio-emotional adjustment in grade 1. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 34, 259–269. 10.1177/0165025409350959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Arslan C. (2009). Anger, self-esteem, and perceived social support in adolescence. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 37, 555–564. 10.2224/sbp.2009.37.4.555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R. F., Sommer K. L. (1997). What do men want? Gender differences and two spheres of belongingness: comment on cross and madson (1997). Psychol. Bull. 122, 38–44. 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Birgani S. A., Sahaghi H., Mousavi S. A. (2015). The relationship between teacher affective support and educational enjoyment with attachment to school male high school students of Ahvaz, Iran. J. Educ. Manag. Stud. 5, 138–144. Available online at: http://www.jems.science-line.com/attachments/article/29/J.%20Educ.%20Manage.%20Stud.,%205(2)%20138-144,%202015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- *Burić I. (2015). The role of social factors in shaping students' test emotions: a mediation analysis of cognitive appraisals. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 18, 785–809. 10.1007/s11218-015-9307-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Cheung S.-K. (1995). Life events, classroom environment, achievement expectation, and depression among early adolescents. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 23, 83–92. 10.2224/sbp.1995.23.1.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Chirkov V. I., Ryan R. M. (2001). Parent and teacher autonomy-support in Russian and US adolescents common effects on well-being and academic motivation. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 32, 618–635. 10.1177/0022022101032005006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu M. M., Chow B. W.-Y. (2011). Classroom discipline across 41 countries: school, economic, and cultural differences. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 42, 516–533. 10.1177/0022022110381115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Clark S. L. (2008). The Role of School, Family, and Peer Support In Moderating the Relationship between Stress and Subjective Well-Being: An Examination of Gender Differences among Early Adolescents Living in an Urban Area, Doctoral dissertation, Loyola University Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1969). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- *Cox A., Duncheon N., McDavid L. (2009). Peers and teachers as sources of relatedness perceptions, motivation, and affective responses in physical education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 80, 765–773. 10.1080/02701367.2009.10599618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Demaray M. K., Malecki C. K., Davidson L. M., Hodgson K. K., Rebus P. J. (2005). The relationship between social support and student adjustment: a longitudinal analysis. Psychol. Sch. 42:691 10.1002/pits.20120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Yu G. L. (2007). The development and application of an academic emotions questionnaire. Acta Psychol. Sin. 39, 852–860. Available online at: https://wenku.baidu.com/view/00b64751ad02de80d4d840f8.html [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Smith G. D., Schneider M., Minder C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 315, 629–634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Elmelid A., Stickley A., Lindblad F., Schwab-Stone M., Henrich C. C., Ruchkin V. (2015). Depressive symptoms, anxiety and academic motivation in youth: do schools and families make a difference? J. Adolesc. 45, 174–182. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Federici R. A., Skaalvik E. M. (2014). Students' perceptions of emotional and instrumental teacher support: relations with motivational and emotional responses. Int. Educ. Stud. 7, 21–26. 10.5539/ies.v7n1p21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser B. J. (1998). Classroom environment instruments: development, validity and applications. Learn. Environ. Res. 1, 7–34. 10.1023/A:1009932514731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Frenzel A. C., Goetz T., Lüdtke O., Pekrun R., Sutton R. E. (2009). Emotional transmission in the classroom: exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 705–716. 10.1037/a0014695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frenzel A. C., Thrash T. M., Pekrun R., Goetz T. (2007). Achievement emotions in Germany and China a cross-cultural validation of the academic emotions questionnaire—mathematics. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 38, 302–309. 10.1177/0022022107300276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Gläser-Zikuda M., Fuß S. (2008). Impact of teacher competencies on student emotions: a multi-method approach. Int. J. Educ. Res. 47, 136–147. 10.1016/j.ijer.2007.11.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Hagenauer G., Hascher T. (2010). Learning enjoyment in early adolescence. Educ. Res. Eval. 16, 495–516. 10.1080/13803611.2010.550499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Hill H. M., Levermore M., Twaite J., Jones L. P. (1996). Exposure to community violence and social support as predictors of anxiety and social and emotional behavior among African American children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 5, 399–414. 10.1007/BF02233862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Huang S., Eslami Z., Hu R.-J. S. (2010). The relationship between teacher and peer support and English-language learners' anxiety. English Lang. Teach. 3, 32–40. 10.5539/elt.v3n1p32 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huizhen S. (2014). Attention to the inheritance of traditional cultural spirit in ancient literature education, in Paper presented at the 2014 2nd International Conference on Advances in Social Science, Humanities, and Management (ASSHM-14) (Guangzhou: ). [Google Scholar]

- *Jia Y., Way N., Ling G., Yoshikawa H., Chen X., Hughes D., et al. (2009). The influence of student perceptions of school climate on socioemotional and academic adjustment: a comparison of Chinese and American adolescents. Child Dev. 80, 1514–1530. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Karabenick S. A., Sharma R. (1994). Perceived teacher support of student questioning in the college classroom: its relation to student characteristics and role in the classroom questioning process. J. Educ. Psychol. 86, 90–103. 10.1037/0022-0663.86.1.90 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Karagiannidis Y., Barkoukis V., Gourgoulis V., Kosta G., Antoniou P. (2015). The role of motivation and metacognition on the development of cognitive and affective responses in physical education lessons: a self-determination approach/O papel da motivação e metacognição no desenvolvimento das respostas afetiva e cognitiva em aulas de educação física: uma abordagem centrada na teoria da autodeterminação. Motricidade 11, 135–150. 10.6063/motricidade.3661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerres Malecki C., Kilpatrick Demary M. (2002). Measuring perceived social support: development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS). Psychol. Sch. 39, 1–18. 10.1002/pits.10004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *King R. B., McInerney D. M., Watkins D. A. (2012). How you think about your intelligence determines how you feel in school: the role of theories of intelligence on academic emotions. Learn. Individ. Differ. 22, 814–819. 10.1016/j.lindif.2012.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klem A. M., Connell J. P. (2004). Relationships matter: linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. J. Sch. Health 74, 262–273. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lapointe J. M., Legault F., Batiste S. J. (2005). Teacher interpersonal behavior and adolescents' motivation in mathematics: a comparison of learning disabled, average, and talented students. Int. J. Educ. Res. 43, 39–54. 10.1016/j.ijer.2006.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *LaRusso M. D., Romer D., Selman R. L. (2008). Teachers as builders of respectful school climates: implications for adolescent drug use norms and depressive symptoms in high school. J. Youth Adolesc. 37, 386–398. 10.1007/s10964-007-9212-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawman H. G., Wilson D. (2013). Self-Determination Theory. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- *Lazarides R., Ittel A. (2013). Mathematics interest and achievement: what role do perceived parent and teacher support play? a longitudinal analysis. Int. J. Gender Sci. Tech. 5, 207–231. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260690091 [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey M. W., Wilson D. B. (2001). Practical Meta-Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- *Liu W., Mei J., Tian L., Huebner E. S. (2016). Age and gender differences in the relation between school-related social support and subjective well-being in school among students. Soc. Indic. Res. 125, 1065–1083. 10.1007/s11205-015-0873-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi C., Prino L. E., Marengo D., Settanni M. (2016). Student-teacher relationships as a protective factor for school adjustment during the transition from middle to high school. Front. Psychol. 7:1988. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ludwig K. A., Warren J. S. (2009). Community violence, school-related protective factors, and psychosocial outcomes in urban youth. Psychol. Sch. 46, 1061–1073. 10.1002/pits.20444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz C. A. (1996). Engendered emotion: gender, power, and the rhetoric of emotional control in american discourse, in Language and the Politics of Emotion, eds Lutz C. A., Abu-Lughod L. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ), 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- *MacPhail S. S. (2012). Perceived Competence and Depressive Symptoms in Children with Reading Problems, Doctoral dissertation, Fordham University. [Google Scholar]

- Malecki C. K., Elliott S. N. (1999). Adolescents' ratings of perceived social support and its importance: validation of the student social support scale. Psychol. Sch. 36, 473–483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Martínez R. S., Aricak O. T., Graves M. N., Peters-Myszak J., Nellis L. (2011). Changes in perceived social support and socioemotional adjustment across the elementary to junior high school transition. J. Youth Adolesc. 40, 519–530. 10.1007/s10964-010-9572-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McMahon S. D., Coker C., Parnes A. L. (2013). Environmental stressors, social support, and internalizing symptoms among African American youth. J. Community Psychol. 41, 615–630. 10.1002/jcop.21560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A., Ferguson E., Byrne I. (2000). Pupils' causal attributions for difficult classroom behaviour. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 70, 85–96. 10.1348/000709900157985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S., DellaMattera J. (2011). Teacher support and student's self-efficacy beliefs. J. Contemp. Issues Educ. 5, 24–35. 10.20355/C5X30Q [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Murberg T. A., Bru E. (2009). The relationships between negative life events, perceived support in the school environment and depressive symptoms among Norwegian senior high school students: a prospective study. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 12, 361–370. 10.1007/s11218-008-9083-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myint K. L., Fisher D. L. (2001). Classroom environment and teachers' cultural background in secondary science classes in an Asian context, in Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Australian Association for Research in Education (Perth: ). [Google Scholar]

- *Neville K. (2008). Optimal Balanced Affect: Associations with Urban Adolescents' Perceived Social Support and Life Satisfaction, Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. [Google Scholar]

- *Nilsen W., Karevold E., Røysamb E., Gustavson K., Mathiesen K. S. (2013). Social skills and depressive symptoms across adolescence: social support as a mediator in girls versus boys. J. Adolesc. 36, 11–20. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ommundsen Y., Kvalø S. E. (2007). Autonomy–mastery, supportive or performance focused? Different teacher behaviours and pupils' outcomes in physical education. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 51, 385–413. 10.1080/00313830701485551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Ommundsen Y., Klasson-Heggeb,ø L., Anderssen S. A. (2006). Psycho-social and environmental correlates of location-specific physical activity among 9-and 15-year-old Norwegian boys and girls: the European youth heart study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 3, 1–13. 10.1186/1479-5868-3-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Pan Y.-H. (2014). Relationships among teachers' self-efficacy and students' motivation, atmosphere, and satisfaction in physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 33, 68–92. 10.1123/jtpe.2013-0069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun R., Goetz T., Titz W., Perry R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students' self-regulated learning and achievement: a program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 37, 91–105. 10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Piechurska-Kuciel E. (2011). Perceived teacher support and language anxiety in Polish secondary school EFL learners. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 1, 83–100. 10.14746/ssllt.2011.1.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Reddy R., Rhodes J. E., Mulhall P. (2003). The influence of teacher support on student adjustment in the middle school years: a latent growth curve study. Dev. Psychopathol. 15, 119–138. 10.1017/S0954579403000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rey R. B., Smith A. L., Yoon J., Somers C., Barnett D. (2007). Relationships between teachers and urban African American children the role of informant. Sch. Psychol. Int. 28, 346–364. 10.1177/0143034307078545 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Rueger S. Y., Malecki C. K., Demaray M. K. (2008). Gender differences in the relationship between perceived social support and student adjustment during early adolescence. School Psychol. Q. 23, 496–514. 10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.496 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Ryan A. M., Patrick H., Shim S.-O. (2005). Differential profiles of students identified by their teacher as having avoidant, appropriate, or dependent help-seeking tendencies in the classroom. J. Educ. Psychol. 97, 275–285. 10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan R. M., Deci E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–77. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sahaghi H., Alipour S., Yailagh M. S. (2015). The causal relationship between of perceived teacher affective support with english performance, mediated by academic enjoy, academic self-efficacy and academic effort among first grade high school male student of Ahvaz (Iran). Int. J. Rev. Life Sci. 5, 547–554. 10.3126/ijls.v10i1.14510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Sakiz G. (2012). Perceived instructor affective support in relation to academic emotions and motivation in college. Educ. Psychol. 32, 63–79. 10.1080/01443410.2011.625611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Sakiz G., Pape S. J., Hoy A. W. (2012). Does perceived teacher affective support matter for middle school students in mathematics classrooms? J. Sch. Psychol. 50, 235–255. 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sakiz G., Pape S. J., Woolfolk Hoy A. (2007). Teacher Affective Support and Its Impact on Early Adolescents, in Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association (San Francisco, CA: ). [Google Scholar]

- *Skinner E. A., Belmont M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. J. Educ. Psychol. 85, 571–581. 10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E., Furrer C., Marchand G., Kindermann T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: part of a larger motivational dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 100, 765–781. 10.1037/a0012840 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Sorić I. (2007). The relationship between self-efficacy, causal attributions and experienced emotions in academic context, Book of Selected Proceedings: 15th Psychology Days in Zadar (University of Zadar; ). [Google Scholar]

- *Sun R. C., Hui E. K. (2007). Psychosocial factors contributing to adolescent suicidal ideation. J. Youth Adolesc. 36, 775–786. 10.1007/s10964-006-9139-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Sun R. C., Hui E. K., Watkins D. (2006). Towards a model of suicidal ideation for Hong Kong Chinese adolescents. J. Adolesc. 29, 209–224. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Sylva K., Melhuish E., Sammons P., Siraj-Blatchford I., Taggart B. (2012). Effective Pre-School, Primary and Secondary Education Project (EPPSE 3-14): Final Report from the Key Stage 3 Phase: Influences on Students' Development from age 11–14. London: Department for Education, University of London. [Google Scholar]

- *Tanigawa D., Furlong M. J., Felix E. D., Sharkey J. D. (2011). The protective role of perceived social support against the manifestation of depressive symptoms in peer victims. J. Sch. Violence 10, 393–412. 10.1080/15388220.2011.602614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tardy C. H. (1985). Social support measurement. Am. J. Community Psychol. 13, 187–202. 10.1007/BF00905728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Taylor B. A. (2003). The Influence of Classroom Environment on High School Students' Mathematics Anxiety, Doctoral dissertation, Curtin University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B. A., Fraser B. J. (2003). The Influence of Classroom Environment on High School Students' Mathematics Anxiety. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 476644.

- *Telan P. (2000). Teacher-Student Relationships and the Link to Academic Adjustment and Emotional Well-Being in Early Adolescence, Doctoral dissertation, Florida International University. [Google Scholar]

- Teng Z., Liu Y., Guo C. (2015). A meta-analysis of the relationship between self-esteem and aggression among Chinese students. Aggress. Violent Behav. 21, 45–54. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Tian L., Liu B., Huang S., Huebner E. S. (2013). Perceived social support and school well-being among Chinese early and middle adolescents: the mediational role of self-esteem. Soc. Indic. Res. 113, 991–1008. 10.1007/s11205-012-0123-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Van Ryzin M. J. (2011). Protective factors at school: reciprocal effects among adolescents' perceptions of the school environment, engagement in learning, and hope. J. Youth Adolesc. 40, 1568–1580. 10.1007/s10964-011-9637-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Van Ryzin M. J., Gravely A. A., Roseth C. J. (2009). Autonomy, belongingness, and engagement in school as contributors to adolescent psychological well-being. J. Youth Adolesc. 38, 1–12. 10.1007/s10964-007-9257-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Wang M.-T. (2009). School climate support for behavioral and psychological adjustment: testing the mediating effect of social competence. Sch. Psychol. Q. 24, 240–251. 10.1037/a0017999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Wang M.-T., Eccles J. S. (2013). School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: a longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learn. Instruction 28, 12–23. 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Way N., Reddy R., Rhodes J. (2007). Students' perceptions of school climate during the middle school years: associations with trajectories of psychological and behavioral adjustment. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 40, 194–213. 10.1007/s10464-007-9143-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Weber K., Martin M., Patterson B. (2001). Teacher behavior, student interest and affective learning: putting theory to practice. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 29, 71–90. 10.1080/00909880128101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wellborn J., Connell J. (1987). Manual for the Rochester Assessment Package for Schools. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester. [Google Scholar]

- *Wentzel K. R. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: the role of parents, teachers, and peers. J. Educ. Psychol. 90, 202–209. 10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Yang L., Sin K.-F., Lui M. (2015). Social, emotional, and academic functioning of children with SEN integrated in Hong Kong primary schools. Asia Pacific Educ. Res. 24, 545–555. 10.1007/s40299-014-0198-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]