ABSTRACT

Candida auris is a newly identified species causing invasive candidemia and candidiasis. It has broad multidrug resistance (MDR) not observed for other pathogenic Candida species. Histatin 5 (Hst 5) is a well-studied salivary cationic peptide with significant antifungal activity against Candida albicans and is an attractive candidate for treating MDR fungi, since antimicrobial peptides induce minimal drug resistance. We investigated the susceptibility of C. auris to Hst 5 and neutrophils, two first-line innate defenses in the human host. The majority of C. auris clinical isolates, including fluconazole-resistant strains, were highly sensitive to Hst 5: 55 to 90% of cells were killed by use of 7.5 μM Hst 5. Hst 5 was translocated to the cytosol and vacuole in C. auris cells; such translocation is required for the killing of C. albicans by Hst 5. The inverse relationship between fluconazole resistance and Hst 5 killing suggests different cellular targets for Hst 5 than for fluconazole. C. auris showed higher tolerance to oxidative stress than C. albicans, and higher survival within neutrophils, which correlated with resistance to oxidative stress in vitro. Thus, resistance to reactive oxygen species (ROS) is likely one, though not the only, important factor in the killing of C. auris by neutrophils. Hst 5 has broad and potent candidacidal activity, enabling it to combat MDR C. auris strains effectively.

KEYWORDS: Candida auris, histatin, innate host defense, neutrophils

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of simultaneous resistance to different antifungal classes, i.e., multidrug resistance (MDR), poses a serious threat for the treatment of fungal infections, further limiting therapeutic choices. Compared to other fungal pathogens, Candida species predominate as the leading cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections in the United States (1, 2), partly due to their intrinsic drug resistance. Resistance to a single class of antifungal drugs has been observed among different Candida species in many clinical settings as a consequence of genomic mutations (3–5). Widespread and prolonged use of azoles has led to the rapid development of MDR among clinical isolates of Candida albicans, mainly through the overexpression of multidrug transporters (6). The highest rates of MDR to both azoles and echinocandins have been reported for Candida glabrata (7), a phenomenon that is likely attributable to its haploid genome (8). This rapid emergence of MDR fungal pathogens worsens the risk of candidemia, along with the appearance of a recently identified Candida species, Candida auris (9, 10).

C. auris was first identified from the ear discharge of a Japanese woman in 2009 (11), and subsequently C. auris infections, with multidrug resistance to all the major antifungal drug classes (azoles, pyridine analogs, polyenes, and echinocandins), have been reported worldwide (10, 12–16). The majority of C. auris outbreaks have been found in health care settings as secondary infections, possibly through horizontal transmission (14, 17, 18). On the basis of ribosomal DNA sequences, C. auris falls into four distinct phylogenic clusters that differ widely from each other and are grouped by the geographical origins of the isolates, designated as East Asia, South Asia, Africa, and South America (15, 18). These geographical clades possess high genomic plasticity, as shown by genome architecture and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variations (12, 15). C. auris is strictly a unicellular yeast with no apparent filamentous phase, although certain isolates have a high tendency to form aggregates and thin biofilms (19, 20). Some isolates are more thermotolerant than prototypical Candida species and also grow at 42°C (12, 19, 20). In the absence of molecular identification, C. auris is often misdiagnosed as Candida haemulonii, a phylogenetically related drug-resistant organism that is an infrequent cause of human fungemia (21–23).

Although the antifungal resistance profiles of C. auris isolates vary, a common characteristic of all C. auris isolates is a higher antifungal-drug MIC than that for C. albicans. Both planktonic and biofilm cells of four different C. auris isolates exhibited fluconazole MICs of >32 mg/liter (20), while another study of 54 different isolates reported a fluconazole MIC range of 4 to 256 mg/liter (15). Also, C. auris had significantly higher rhodamine 6G efflux activity than C. glabrata or C. haemulonii, suggesting ABC (ATP-binding cassette)-type drug efflux activity (12), a key mechanism for drug resistance among many fungi. This is supported by the identification of putative ABC and major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters from draft genome analyses of C. auris (24, 25).

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) play a pivotal role in innate immunity in humans and are attractive as potential therapeutic drugs, since they induce no or minimal MDR in target fungi (26). Among them, the histidine-rich salivary protein histatin 5 (Hst 5) has shown promising antifungal activity against C. albicans through an energy-dependent, nonlytic process (reviewed in reference 27). Hst 5 has no significant microbicidal activity toward oral commensal bacteria, although it has the ability to kill certain nosocomial bacterial pathogens with high risk for drug resistance (28). This broad antimicrobial activity of Hst 5 is attributable to multiple killing mechanisms that have not yet been fully understood at a molecular level (reviewed in reference 27). Although current epidemiological data provide no evidence of C. auris being isolated from the oral cavity, this pathogen can spread through human contact and forms biofilms readily (18–20). Therefore, the oral cavity may be a potential site for colonization by this organism.

In this study, we evaluated the in vitro antifungal activity of Hst 5 against a panel of C. auris clinical isolates from different geographical sites. We found that Hst 5 can effectively kill most C. auris clinical isolates, regardless of their azole-resistant status. We also observed that C. auris strains are highly tolerant to oxidative stress, and this was reflected in their reduced susceptibility to human neutrophil killing, but not to Hst 5 killing. Therefore, Hst 5 and potentially other antimicrobial peptides may be considered as therapeutic agents for the treatment of MDR C. auris.

RESULTS

Morphological variation in clinical isolates of C. auris.

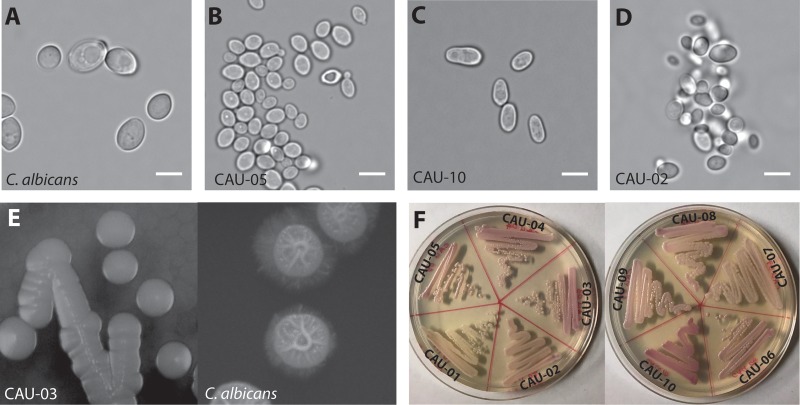

The C. auris collection used in this study showed little diversity in overall colony morphology on solid media, regardless of the geographical origin of the isolate (Table 1). All C. auris strains had similar growth rates (average generation time, 51.8 min) except for CAU-01 (generation time, 91.2 min), which had a much lower growth rate. However, other morphological differences from C. albicans were observed among the isolates. Most C. auris cells were significantly smaller (Feret diameter, 4.73 ± 0.19 μm, except for CAU-10) than C. albicans cells (Feret diameter, 5.31 ± 1.1 μm) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A) and grew as unicellular yeasts, with either spherical or oval shapes (Fig. 1B) or an elongated ellipsoidal morphology (Fig. 1C). Half of the C. auris isolates (CAU-02, CAU-03, CAU-04, CAU-05, and CAU-06) showed a highly aggregative phenotype (Fig. 1D), while the others grew as single cells. None of the strains formed hyphae, pseudohyphae, or chlamydospores under inducing conditions (Table 1); this was reflected in their smooth-colony morphology on Spider medium, in contrast to the wrinkled appearance of C. albicans cells (Fig. 1E). Interestingly, half of the C. auris isolates formed light-pink colonies on CHROMagar (CAU-01, CAU-02, CAU-07, CAU-08, and CAU-09), while the remainder formed dark-pink colonies, suggesting that this collection consists of two different subtypes (Fig. 1F). Based on these differences, we expected differences in susceptibility to Hst 5 among the isolates.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic characterization of C. auris isolates used in this study

| Strain no. | C. auris strain designation | Cell shape | Aggregationa | Hyphae or pseudohyphaeb | Colony morphology on Spider medium | Color on CHROMagarc | Chlamydospore productiond |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAU-01 | AR-BANK#0381 | Ellipsoidal | Single cells | None | Smooth colonies | Pink | None |

| CAU-02 | AR-BANK#0382 | Ellipsoidal | Aggregative | None | Smooth colonies | Pink | None |

| CAU-03 | AR-BANK#0383 | Spherical to ovoid | Aggregative | None | Smooth colonies | Dark pink | None |

| CAU-04 | AR-BANK#0384 | Spherical to ovoid | Aggregative | None | Smooth colonies | Dark pink | None |

| CAU-05 | AR-BANK#0385 | Spherical to ovoid | Aggregative | None | Smooth colonies | Dark pink | None |

| CAU-06 | AR-BANK#0386 | Spherical to ovoid | Aggregative | None | Smooth colonies | Dark pink | None |

| CAU-07 | AR-BANK#0387 | Ellipsoidal | Single cells | None | Smooth colonies | Pink | None |

| CAU-08 | AR-BANK#0388 | Spherical to ovoid | Single cells | None | Smooth colonies | Pink | None |

| CAU-09 | AR-BANK#0389 | Spherical to ovoid | Single cells | None | Smooth colonies | Pink | None |

| CAU-10 | AR-BANK#0390 | Ellipsoidal | Single cells | None | Smooth colonies | Dark pink | None |

Cells were mixed in PBS and were vortexed at high speed for 1 min before microscopy to detect cell aggregation.

Hyphal formation was assessed in BD Difco yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) broth, yeast nitrogen base (YNB) with ammonium sulfate supplemented with 1.25% N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, YPD broth with 10% fetal bovine serum, and Spider medium. Each medium was inoculated with 1 × 107 cells/ml, and cells were incubated at 37°C with agitation for as long as 24 h.

C. auris strains were streak-inoculated in CHROMagar Candida medium and were incubated at 37°C for 48 h in order to observe colony morphology.

C. auris strains were inoculated onto corn meal agar and rice extract agar using the Dalmau technique, incubated at 23°C in the dark for as long as 2 weeks, and observed microscopically for the presence of chlamydospores.

FIG 1.

Basic morphology of the C. auris clinical isolates used in this study. (A to D) Micrographs of C. albicans SC5314, consisting of large ovoid cells (A), C. auris strains consisting of spherical to ovoid cells (CAU-05 shown) (B) or ellipsoidal cells (CAU-10 shown) (C), and some highly aggregative strains (CAU-02 shown) (D). (E) Colony morphology of C. auris (CAU-03 shown). C. auris forms smooth, unwrinkled colonies on Spider medium plates after 7 days of incubation at 37°C, while C. albicans SC5314 forms rough colonies. (F) C. auris strains form smooth, light- to dark-pink circular colonies on CHROMagar plates after incubation for 48 h at 37°C. Bars, 5 μm.

Fluconazole-resistant C. auris strains are susceptible to Hst 5 killing.

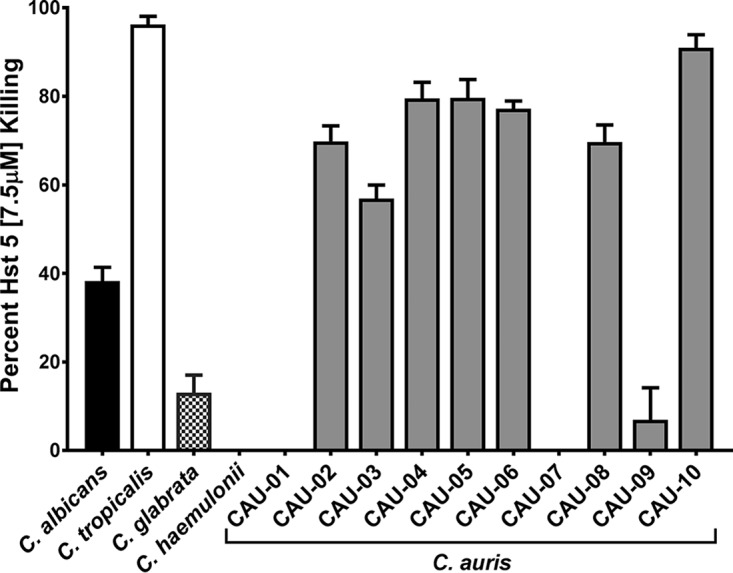

In order to determine the candidacidal activity of Hst 5 against C. auris, clinical isolates were treated with Hst 5 (7.5 μM, 15 μM, and 30 μM, corresponding to 22.77 μg/ml, 45.54 μg/ml, and 91.09 μg/ml, respectively) for 60 min and were compared with the reference strains C. albicans SC5314, Candida tropicalis ATCC 750, and C. glabrata BG2, and with a clinical isolate of C. haemulonii (AR-BANK#0393), to determine relative killing. At low Hst 5 doses (7.5 μM), with which only 38% killing of C. albicans occurred, we observed significantly higher levels of killing (58 to 90%) for most C. auris isolates (CAU-02, CAU-03, CAU-04, CAU-05, CAU-06, CAU-08, and CAU-10), a sensitivity comparable to that of another Candida species, C. tropicalis (Fig. 2). Only three isolates (CAU-01, CAU-07, and CAU-09) showed no or low killing, similar to the low levels of killing found for both C. glabrata and C. haemulonii (the closest phylogenetic relative of C. auris) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, increasing Hst 5 doses up to 30 μM did not result in improved killing of these Hst 5-resistant strains (data not shown). However, there was no relationship between Hst 5 sensitivity and C. auris cell or colony morphology (Fig. 1).

FIG 2.

Many C. auris isolates are susceptible to Hst 5. C. auris cells in exponential phase were exposed to 7.5 μM Hst 5 in 10 mM NaPB for 60 min at 30°C; then aliquots containing 400 cells were plated to determine the percentage of killing. C. albicans showed 38% killing, while seven C. auris isolates (CAU-02, CAU-03, CAU-04, CAU-05, CAU-06, CAU-08, and CAU-10) showed significantly (P < 0.001) higher killing (55 to 90%), and three strains were insensitive (CAU-01, CAU-07, and CAU-09). Interestingly, C. glabrata and C. haemulonii, the closest phylogenetic relatives of C. auris, showed low susceptibility to Hst 5. Percentages of killing are shown as means and standard deviations for at least three independent replicates for each isolate, and significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison test.

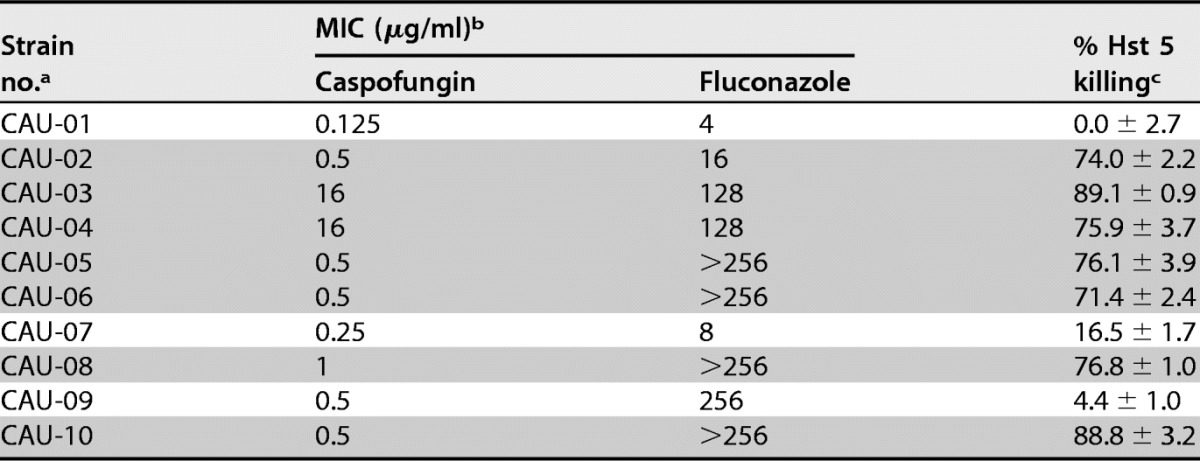

To determine whether these Hst 5-resistant strains were susceptible to other antifungal drugs, we compared the percentages of Hst 5 (15 μM) killing with fluconazole and caspofungin MIC values as reported by the FDA-CDC Antimicrobial Resistance (AR) Isolate Bank (Table 2). Surprisingly, we found that for C. auris strains CAU-01 and CAU-07, which showed little or no killing by Hst 5 (0 and 16.5%, respectively), both fluconazole and caspofungin MICs were very low. In contrast, the strains that showed the highest sensitivity to Hst 5 (71 to 89% killing) had more resistance to fluconazole (CAU-05, CAU-06, CAU-08, and CAU-10 [MIC, >256 μg/ml]) and relatively moderate sensitivity to caspofungin. The only exception to this inverse relationship was C. auris strain CAU-09, which showed poor killing by both Hst 5 and fluconazole but was moderately sensitive to caspofungin. Strikingly, the overall pattern we found was that fluconazole-resistant C. auris strains were highly sensitive to Hst 5-mediated killing (Table 2), suggesting a basic difference between the mechanisms of action of fluconazole and Hst 5. Due to the limited MIC range of caspofungin compared to that of fluconazole, we did not compare caspofungin sensitivity to Hst 5 killing.

TABLE 2.

Cidal activity of Hst 5 against C. auris strains with fluconazole and caspofungin MICs

a The strains with higher fluconazole resistance (MIC, ≥16 μg/ml) that remain susceptible to Hst 5 killing are shaded.

b From the FDA-CDC Antimicrobial Resistance Isolate Bank, Candida auris Panel (https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/resistance-bank/currently-available.html; accessed August 2017).

c Hst 5 was used at a 15 μM (45.54 μg/ml) concentration.

C. auris cells rapidly take up Hst 5 with cytosolic and vacuolar localization.

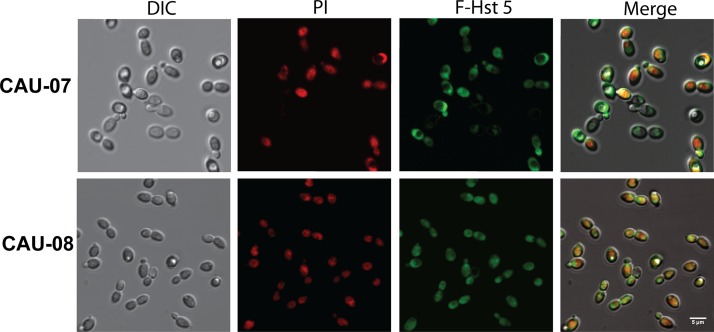

Since we showed previously that transporter-mediated intracellular uptake of Hst 5 is essential for its killing of Candida species (29), we examined the translocation of fluorescently labeled Hst 5 (F-Hst 5) and propidium iodide (PI) by C. auris using time-lapse confocal microscopy. We analyzed F-Hst 5 uptake by C. auris using an isolate for which Hst 5 had low killing efficiency (CAU-07) and one for which it had a higher killing efficiency (CAU-08) in order to determine whether Hst 5-resistant isolates have any defects in Hst 5 uptake. Both Hst 5-resistant (CAU-07) and Hst 5-sensitive (CAU-08) C. auris isolates transported F-Hst 5 to the cytosol after 30 min (Fig. 3) in a manner similar to that of the C. albicans control strain (data not shown). As we observed previously for C. albicans (30), F-Hst 5 was visible at the surfaces of most C. auris cells within 1 min, followed by the cytosolic localization of F-Hst 5 after 5 min. PI uptake began slightly after the initial F-Hst 5 uptake, and the Hst 5-resistant C. auris isolate (CAU-07) showed fewer cells with cytosolic Hst 5 and PI at 30 min (Fig. 3). Hst 5 uptake resulted in a clear change in cell topography in both isolates, with an expanded vacuole manifesting as a large, defined indent. In instances where the enlarged vacuole ruptured, cells remained oval but were smaller and more rounded. By 30 min, many cells had uniform cytosolic/vacuolar staining with F-Hst 5 and PI, but nearly all cells of the Hst 5-sensitive isolate CAU-08 were dark and opaque when observed by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, indicating cell death, while many cells of the resistant isolate CAU-07 remained bright (viable) (Fig. 3). Thus, the progression of Hst 5 and PI uptake along with vacuolar rupture was similar to what we had observed previously for C. albicans cells (30); however, the extent of cell death differed between these two C. auris isolates.

FIG 3.

F-Hst 5 is taken up by C. auris cells. F-Hst 5 (30 μM) and PI (0.5 μM) were added to C. auris cells adherent to a glass coverslip, and intracellular uptake was imaged after 30 min at 23°C using DIC and fluorescence confocal microscopy. Regardless of the killing efficiency of Hst 5, both CAU-07 and CAU-08 transported F-Hst 5 to the cytosol (as visualized by green florescence), resulting in a change in cell topology followed by cell death (as visualized by red PI staining). Bar, 5 μm.

C. auris can tolerate higher levels of oxidative stress than C. albicans.

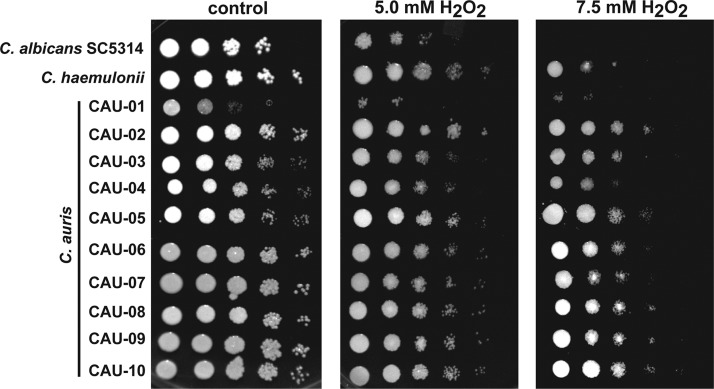

Since adaptive responses to oxidative stresses generated by Hst 5 may contribute to the sensitivity of C. auris to this peptide, we compared the oxidative and osmotic stress tolerances of C. auris strains (Fig. 4). C. auris strains showed no difference from C. albicans in growth under osmotic stress induced by either NaCl or sorbitol (data not shown). However, all C. auris isolates except CAU-01 were more resistant to oxidative stress than C. albicans, which showed no growth at the highest (7.5 mM) concentration of H2O2 (Fig. 4). The close relative C. haemulonii demonstrated a level of oxidative stress resistance similar to that of C. auris strains. Although CAU-01 was highly sensitive to oxidative stress (failing to grow abundantly in the presence of 7.5 mM H2O2 even after 48 h of incubation), this strain was completely insensitive to Hst 5 killing, showing that oxidative stress responses alone are not the basis for the resistance of CAU-01 to Hst 5.

FIG 4.

C. auris strains tolerate higher levels of oxidative stress than C. albicans. For spot assays, yeast cells in the mid-log-growth phase were serially diluted, inoculated onto YPD plates supplemented with 5 or 7.5 mM H2O2, and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. All C. auris isolates except CAU-01 showed higher tolerance of H2O2 stress at 7.5 mM than the reference strain, C. albicans SC5314.

The survival of C. auris strains in human neutrophils is independent of Hst 5 killing but not of oxidative stress sensitivity.

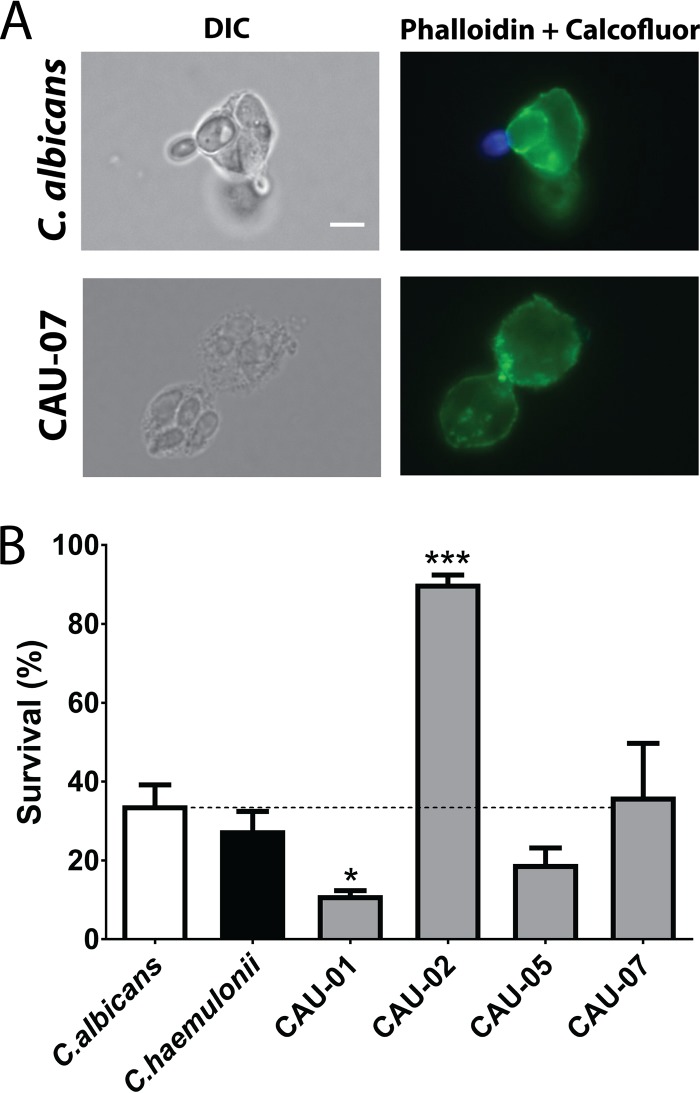

Since human neutrophils are primary effector cells in preventing C. albicans infection through phagocytosis and subsequent killing via reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced oxidative stress, we expected that C. auris strains with high oxidative stress tolerance might be relatively resistant to neutrophil killing. Therefore, we assessed both the phagocytic indexes and the percentages of survival of ingested cells of four C. auris strains, the Hst 5-resistant isolates CAU-01 and CAU-07 and the Hst 5-sensitive isolates CAU-02 and CAU-05. These strains showed variable responses to oxidative stress; CAU-02 was the most tolerant. C. albicans and C. haemulonii were used as controls. The four C. auris strains had similar phagocytic indices (0.08 to 0.11), which were not statistically different from that of either the C. albicans or the C. haemulonii control strain. Thus, the uptake of C. auris cells by human neutrophils (Fig. 5A) was quantitatively similar to that of C. albicans. As expected, we observed a significant reduction in the survival of CAU-01 within human neutrophils (Fig. 5B), which corresponded with its reduced tolerance to oxidative stress. Furthermore, CAU-02, the C. auris strain with the highest tolerance of H2O2, also showed significantly higher survival than the control strains in neutrophil phagosomes. However, we found similar intracellular survival for CAU-05, CAU-07, and C. albicans. The differences in Hst 5 sensitivity among those strains did not correspond with neutrophil survival. Therefore, these differences in oxidative stress tolerance likely contribute to neutrophil killing profiles.

FIG 5.

C. auris strains have differential susceptibility to intracellular killing by human neutrophils. (A) C. auris cells are phagocytosed by human neutrophils. Shown are overlay images of green (neutrophils stained by phalloidin dye) and blue (nonphagocytosed yeast cells stained with calcofluor white) fluorescence channels. The bright-field view shows internalized C. auris cells. Bar, 5 μm. (B) C. auris strains were coincubated with human neutrophils for 3 h; phagocytosed yeast was released by lysing neutrophils; and intracellular survival was determined by plating. Results represent means ± standard deviations. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett multiple-comparison test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Over the last decade, there has been an increase in the incidence of the newly discovered species C. auris, particularly as a nosocomial pathogen. C. auris is resistant to multiple classes of antifungal drugs (9, 15, 17, 31), but there are no reports in the literature on whether C. auris is susceptible to antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). AMPs have little or no toxicity toward human cells and do not induce antimicrobial resistance; therefore, they have been proposed as the “next generation of antibiotics” (reviewed in references 27 and 32). Among AMPs, Hst 5 and Hst 3 have been studied extensively and have antifungal activity against major Candida pathogens, including C. albicans, C. kefyr, C. krusei, C. dubliniensis, and C. parapsilosis (27, 33). In this study, we found that salivary Hst 5 is a potent fungicidal agent for most of the C. auris clinical isolates we tested. Importantly, we discovered that most drug-resistant C. auris strains were highly sensitive to Hst 5.

The C. auris panel used in this study represents all four clades of C. auris isolates identified so far, which are at least 40,000 to 140,000 SNPs apart, forming distinct clones (18). Our initial screening did not detect any significant morphological difference among those different isolates except for their aggregative properties (Table 1) and chromogenic reactions on CHROMagar (Fig. 1F). Also, these phenotypic differences did not show any relationship to differences in Hst 5 susceptibility. Based on the small number of C. auris clinical isolates studied within each geographical clade, we could not statistically correlate differences in Hst 5 susceptibility with any particular global location. We also found that the clinical isolate of C. haemulonii tested here (a species closely related to C. auris) had no susceptibility to Hst 5, suggesting that there is great genomic diversity in this phylogenetically related informal yeast group called Metschnikowiaceae (23), at least in terms of their cellular targets and/or mechanism of susceptibility to Hst 5.

Azoles inhibit the demethylation of lanosterol in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, while echinocandins, such as caspofungin and micafungin, interfere with glucan synthesis, thus disrupting cell walls (34). In contrast, Hst 5 acts on multiple intracellular targets following its uptake, ultimately leading to the leakage of intracellular ions, ion imbalance, and volume loss accompanied by vacuolar disruption (27). Although certain clinical isolates of C. auris were resistant to the killing activity of Hst 5 (Fig. 2), we found that the C. auris isolates examined can take up F-Hst 5, resulting in its intracellular accumulation in a manner similar to that of C. albicans (Fig. 3). Our imaging suggests that the resistance to killing in some C. auris strains might be due to slower uptake. It was intriguing to find that two Hst 5-resistant strains (CAU-01 and CAU-07) were susceptible to both fluconazole and caspofungin (Table 2), further confirming that the fungal targets of Hst 5 are distinct from those of these commonly used antifungal drugs.

Hst 5 uptake in C. albicans is energy dependent. Hst 5 is transported through Dur3p and Dur31p after binding to cell wall β-glucans as well as Ssa1p and Ssa2p (reviewed in reference 27). A draft functional annotation of C. auris has identified the presence of orthologs of many C. albicans metabolite transporters as well as secreted proteases (24, 25), giving evidence for the presence of Hst 5 targets in C. auris. Through a Blastp search, we also identified the presence of putative Ssa proteins in C. auris, including heat shock protein Ssa1 (NCBI accession no. XP_018165346.2), with 88% identity to C. albicans Hsp70p/Ssa1p (orf19.4980/C1_13480W), and C. auris hypothetical protein QG37 01870 (NCBI accession no. XP_018170721.1), with 90% identity to C. albicans Ssa2p (orf19.1065/C1_04300C). Therefore, it is possible that the internalization of Hst 5 by C. auris is facilitated by putative Ssa1p and Ssa2p as for C. albicans.

All C. auris strains, with the exception of CAU-01, were able to tolerate hydrogen peroxide-generated oxidative stress better than C. albicans. This intrinsic capacity to withstand high levels of oxidative stress may contribute to a higher pathogenicity of these strains and was reflected uniformly in their ability to be killed by human neutrophils. As expected, certain C. auris isolates that were less tolerant of oxidative stress were highly sensitive to neutrophil killing (e.g., C. auris CAU-01). Likewise, the more oxidative stress-tolerant strain CAU-02 is highly resistant to neutrophil killing (Fig. 5). However, other oxidative stress-tolerant strains had neutrophil killing levels similar to those of C. albicans. Thus, it is likely that other, nonoxidative mechanisms, such as susceptibility to defensins produced by neutrophils, may be involved for these isolates. The enhanced sensitivity of CAU-01 (which was unable to grow abundantly at 7.5 mM H2O2) to oxidative stress might be due, in part, to its slower growth. The factors that contribute to a low growth rate also contribute to stress tolerance in yeasts (35). However, we did not see any growth (new colonies) at the lowest dilutions or at low cell densities in the presence of a stress agent upon longer incubation (up to 48 h). The direct coupling between the growth rate and general stress responses may indicate possible alterations in the mitochondrial function of this particular isolate. Mitochondrial function is essential for the survival of C. albicans under oxidative stress (36), and mitochondria potentially play a role as a target of Hst 5-mediated killing (reviewed in reference 27), which might explain the low susceptibility of CAU-01 to Hst 5 killing.

The development of antimicrobial drug resistance is not a new phenomenon; pathogenic microorganisms have long been adapting to the constantly changing stresses within the human environment. Although C. auris has not been reported in oral sites to date, possibly due to misdiagnosis, its intrinsic resistance to oxidative stress may facilitate its colonization of this site. We found that Hst 5 has high candidacidal activity against 7 of 10 clinical isolates of C. auris, in particular against those isolates that are fluconazole resistant (Table 2). Hst 5 fungicidal activity in saliva is modulated by many factors, including salivary metals and salts, and its proteolytic cleavage by salivary enzymes or microbial enzymes. Similarly, treatment of C. auris sepsis with Hst 5 may be hindered by blood serum components and salts. However, Hst 5 might be considered for topical mucosal treatment, and since C. auris has a high potential for horizontal transmission via fomites, Hst 5 may serve as an antiseptic agent against multidrug-resistant C. auris.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and reagents.

A panel of Candida auris strains (designated AR-BANK#0381 to AR-BANK#0390) was obtained from the antimicrobial resistance bank of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The strains in this panel, which represents all four geographical clades, are listed in Table 1. Candida albicans SC5314, Candida haemulonii (AR-BANK#0393), Candida glabrata BG2, and Candida tropicalis ATCC 750 were used as comparative Candida strains. All Candida strains were routinely grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD; BD Difco) broth medium at 30°C with shaking at 220 rpm, unless otherwise noted. BD Difco YPD agar plates were used for spot sensitivity assays and were supplemented with H2O2 (2.5 mM, 5.0 mM, and 7.5 mM) for oxidative stress or with NaCl or sorbitol (1 M, 1.5 M) for osmotic stress. Histatin 5 (DSHAKRHHGYKRKFHEKHHSHRGY) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled Hst 5 (F-Hst 5) were synthesized by Genemed Synthesis (San Antonio, TX, USA) and their purity verified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses.

Morphological characterization of the C. auris AR collection.

Due to the variability in morphology of C. auris isolates from different geographical clades, we examined basic morphological features using standard microbiological methods. Cell morphology, filamentation, cell aggregation, colony morphology on CHROMagar Candida medium, and chlamydospore formation were examined as described below. Cell morphology was examined using bright-field microscopy at ×63 magnification, and cells were photographed using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 inverted fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The cell size (Feret diameter) was measured from photomicrographs using ImageJ software (n ≥ 75). Cell aggregation was assessed as described previously (37) using a stationary-phase cell suspension (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 2.0) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (Corning Cellgro) that was vortexed for 1 min and was examined microscopically. For filamentation assays, stationary-phase cells cultured in YPD medium were inoculated (1 × 107 cells/ml) into an inducing medium and were grown at 37°C with agitation at 220 rpm for 24 h. The inducing media used included BD Difco YPD broth, yeast nitrogen base (YNB) with ammonium sulfate (MP Biomedicals) supplemented with 1.25% N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (NAG) (Sigma), YPD with 10% fetal bovine serum (Seradigm), and Spider medium (1% Difco nutrient broth, 1% mannitol, 0.2% dibasic potassium phosphate [pH 7.2]) with or without 1.35% agar (38). For the assessment of colony color, C. auris strains were inoculated in CHROMagar Candida (Paris, France) and were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. For the assessment of chlamydospore formation, C. auris strains were inoculated onto corn meal agar and rice extract agar (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) using the Dalmau technique (38) and were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 2 weeks. The growth rate in YPD liquid cultures was assessed by measuring the OD600 using a Lambda 25 UV-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer) under aerobic conditions and was used to calculate the generation time.

Candidacidal assay.

The candidacidal activity of Hst 5 was tested against C. auris cells using microdilution plate assays as described previously (39). Briefly, overnight cultures at stationary phase were diluted to an OD600 of 0.3 to 0.4 and were then regrown to reach an OD600 of 0.8 to 1.0. Cells were washed twice with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (NaPB), pH 7.4. Then cells (1.5 × 106/ml) were mixed with Hst 5 at 30°C for 60 min with shaking at 220 rpm. Control experiments were carried out without Hst 5 treatment. Cells were then diluted in 10 mM NaPB, and approximately 400 cells were spread onto YPD agar plates. CFU were enumerated after incubation for 24 to 48 h at 30°C. Cell survival was expressed as a percentage relative to the number of untreated control cells, and the percentage of killing was calculated as 1 − (number of colonies from Hst 5-treated cells/number of colonies from control cells). Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Dunnett multiple-comparison test. Differences with a P value of <0.05 were considered significant. All experiments were performed at least three times.

Fluorescence microscopy of F-Hst 5 uptake.

C. auris strains CAU-07 and CAU-08 were grown as described for candidacidal assays and were then resuspended to an OD600 of 1.0 in 10 mM NaPB. Cells (50 μl) were added to chambered slides and were allowed to attach to the coverslip. F-Hst 5 and propidium iodide (PI) were added to cells at concentrations of 30 μM and 0.5 μM, respectively. Confocal DIC microscopy and fluorescence microscopy were performed using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Images were acquired every minute after F-Hst 5 and PI addition for a period of 80 min.

Neutrophil assays.

Whole blood was collected from healthy volunteers by venipuncture into Vacuette EDTA tubes coated with spray-dried K3 EDTA (Greiner Bio-One), according to our approved IRB protocol (protocol 626714). Neutrophils were isolated from the whole blood using 1-Step Polymorphs (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corporation) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After isolation, neutrophils were suspended at 2 × 106/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with l-glutamine (Corning Cellgro) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Seradigm). The purity of neutrophils was determined by Wright-Giemsa staining (Polysciences, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Survival assays were performed as described previously (40) with some modifications. Briefly, C. auris strains grown as for candidacidal assays were washed three times with PBS (Corning Cellgro). C. auris cells (1 × 105) were added to freshly isolated human peripheral blood neutrophils (1 × 106) in a final volume of 500 μl at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1 in 24-well plates (Corning Inc.), in order to achieve 100% uptake of Candida cells by neutrophils. C. auris cells and human neutrophils were coincubated for 3 h at 37°C under 5% CO2. Then 100 μl of 0.25% SDS was added to each well, and the mixture was incubated for 5 min, followed by the addition of 400 μl of ice-cold water for another 5-min incubation to allow neutrophil lysis and the release of internalized C. auris. Cell suspensions were removed from each well by pipetting and were then serially diluted and plated onto YPD agar at 30°C to quantify intracellularly viable yeast cells. Control experiments were carried out by incubating C. auris cells without neutrophils. The percentage of survival was calculated by (recovered Candida CFU after incubation with neutrophils/phagocytic index) × 100.

In parallel, phagocytic index assays were performed as described previously (41), with modifications, in order to obtain the number of C. auris cells internalized by neutrophils. Briefly, human neutrophils and C. auris strains were coincubated in 24-well plates (Corning Inc.) at an MOI of 10:1 (final volume, 500 μl) for 30 min at 37°C under 5% CO2. Cell suspensions were removed by pipetting and were placed in positively charged slides (Globe Scientific Inc.) for 15 min at 23°C to allow cells to adhere. Supernatants were gently removed, and nonphagocytosed C. auris cells were stained with 4 mg/ml of calcofluor white (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 2 min on ice. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in PBS for 30 min at 23°C. After fixation, cells were first washed with ice-cold PBS and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Fisher Bioreagents) in PBS for 5 min. Cells were washed again and were stained with 4 mg/ml Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen) for 5 min at 23°C. Following a final wash using PBS, cells were mounted on a fluorescent mounting medium (Dako) and were covered with a no. 1 cover glass (Knittel Gläser) to visualize neutrophils containing internalized C. auris using an Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 inverted fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). A minimum of 100 neutrophils were observed for each yeast strain tested. Internalized yeasts that were not stained with calcofluor white were counted, and the phagocytic index was calculated by the ratio of the total number of internalized yeast cells to total neutrophils counted. Assays were performed in duplicate, and results are representative of three independent experiments. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett multiple-comparison test on GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Ethics statement.

For neutrophil assays, human peripheral blood cells were obtained from healthy, anonymized volunteer donors at Foster Hall, Department of Oral Biology, University at Buffalo (UB), Buffalo, NY. The donors gave written consent using an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved consent form in accordance with UB IRB-approved protocols (protocol 626714, to Jason Kay).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIDCR grants DE10641 and DE022720 to M.E.

REFERENCES

- 1.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, McAllister-Hollod L, Nadle J, Ray SM, Thompson DL, Wilson LE, Fridkin SK. 2014. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med 370:1198–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. 2004. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis 39:309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen-Pergakes K, Kennedy M, Lees N, Barbuch R, Koegel C, Bard M. 1998. Sequencing, disruption, and characterization of the Candida albicans sterol methyltransferase (ERG6) gene: drug susceptibility studies in erg6 mutants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:1160–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia N, Arthington-Skaggs B, Lee W, Pierson C, Lees N, Eckstein J, Barbuch R, Bard M. 2002. Candida albicans sterol C-14 reductase, encoded by the ERG24 gene, as a potential antifungal target site. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:947–957. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.947-957.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White TC. 1997. Increased mRNA levels of ERG16, CDR, and MDR1 correlate with increases in azole resistance in Candida albicans isolates from a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:1482–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wakieć R, Prasad R, Morschhauser J, Barchiesi F, Borowski E, Milewski S. 2007. Voriconazole and multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. Mycoses 50:109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander BD, Johnson MD, Pfeiffer CD, Jimenez-Ortigosa C, Catania J, Booker R, Castanheira M, Messer SA, Perlin DS, Pfaller MA. 2013. Increasing echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata: clinical failure correlates with presence of FKS mutations and elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations. Clin Infect Dis 56:1724–1732. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanglard D. 2016. Emerging threats in antifungal-resistant fungal pathogens. Front Med (Lausanne) 3:11. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2016.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsay S. 2017. Notes from the field: ongoing transmission of Candida auris in health care facilities—United States, June 2016–May 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66:514–515. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6619a7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallabhaneni S, Kallen A, Tsay S, Chow N, Welsh R, Kerins J, Kemble SK, Pacilli M, Black SR, Landon E, Ridgway J, Palmore TN, Zelzany A, Adams EH, Quinn M, Chaturvedi S, Greenko J, Fernandez R, Southwick K, Furuya EY, Calfee DP, Hamula C, Patel G, Barrett P, Lafaro P, Berkow EL, Moulton-Meissner H, Noble-Wang J, Fagan RP, Jackson BR, Lockhart SR, Litvintseva AP, Chiller TM. 2017. Investigation of the first seven reported cases of Candida auris, a globally emerging invasive, multidrug-resistant fungus—United States, May 2013–August 2016. Am J Transplant 17:296–299. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satoh K, Makimura K, Hasumi Y, Nishiyama Y, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. 2009. Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol Immunol 53:41–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben-Ami R, Berman J, Novikov A, Bash E, Shachor-Meyouhas Y, Zakin S, Maor Y, Tarabia J, Schechner V, Adler A. 2017. Multidrug-resistant Candida haemulonii and C. auris, Tel Aviv, Israel. Emerg Infect Dis 23:195. doi: 10.3201/eid2302.161486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Duggal S, Agarwal K, Prakash A, Singh PK, Jain S, Kathuria S, Randhawa HS, Hagen F, Meis JF. 2013. New clonal strain of Candida auris, Delhi, India. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1670–1673. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee WG, Shin JH, Uh Y, Kang MG, Kim SH, Park KH, Jang HC. 2011. First three reported cases of nosocomial fungemia caused by Candida auris. J Clin Microbiol 49:3139–3142. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00319-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lockhart SR, Etienne KA, Vallabhaneni S, Farooqi J, Chowdhary A, Govender NP, Colombo AL, Calvo B, Cuomo CA, Desjardins CA, Berkow EL, Castanheira M, Magobo RE, Jabeen K, Asqhar RJ, Meis JF, Jackson B, Chiller T, Litvintseva AP. 2017. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses. Clin Infect Dis 64:134–140. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magobo RE, Corcoran C, Seetharam S, Govender NP. 2014. Candida auris-associated candidemia, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1250. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.131765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Meis JF. 2017. Candida auris: a rapidly emerging cause of hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant fungal infections globally. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006290. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lockhart SR, Berkow EL, Chow N, Welsh RM. 2017. Candida auris for the clinical microbiology laboratory: not your grandfather's Candida species. Clin Microbiol Newsl 39:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larkin E, Hager C, Chandra J, Mukherjee PK, Retuerto M, Salem I, Long L, Isham N, Kovanda L, Borroto-Esoda K. 2017. The emerging pathogen Candida auris: growth phenotype, virulence factors, activity of antifungals, and effect of SCY-078, a novel glucan synthesis inhibitor, on growth morphology and biofilm formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02396-. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02396-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherry L, Ramage G, Kean R, Borman A, Johnson EM, Richardson MD, Rautemaa-Richardson R. 2017. Biofilm-forming capability of highly virulent, multidrug-resistant Candida auris. Emerg Infect Dis 23:328. doi: 10.3201/eid2302.161320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gargeya IB, Pruitt WR, Meyer SA, Ahearn DG. 1991. Candida haemulonii from clinical specimens in the USA. J Med Vet Mycol 29:335–338. doi: 10.1080/02681219180000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan ZU, Al-Sweih NA, Ahmad S, Al-Kazemi N, Khan S, Joseph L, Chandy R. 2007. Outbreak of fungemia among neonates caused by Candida haemulonii resistant to amphotericin B, itraconazole, and fluconazole. J Clin Microbiol 45:2025–2027. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00222-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kathuria S, Singh PK, Sharma C, Prakash A, Masih A, Kumar A, Meis JF, Chowdhary A. 2015. Multidrug-resistant Candida auris misidentified as Candida haemulonii: characterization by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry and DNA sequencing and its antifungal susceptibility profile variability by Vitek 2, CLSI broth microdilution, and Etest method. J Clin Microbiol 53:1823–1830. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00367-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatterjee S, Alampalli SV, Nageshan RK, Chettiar ST, Joshi S, Tatu US. 2015. Draft genome of a commonly misdiagnosed multidrug resistant pathogen Candida auris. BMC Genomics 16:686. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1863-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma C, Kumar N, Pandey R, Meis J, Chowdhary A. 2016. Whole genome sequencing of emerging multidrug resistant Candida auris isolates in India demonstrates low genetic variation. New Microbes New Infect 13:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batoni G, Maisetta G, Brancatisano FL, Esin S, Campa M. 2011. Use of antimicrobial peptides against microbial biofilms: advantages and limits. Curr Med Chem 18:256–279. doi: 10.2174/092986711794088399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puri S, Edgerton M. 2014. How does it kill? Understanding the candidacidal mechanism of salivary histatin 5. Eukaryot Cell 13:958–964. doi: 10.1128/EC.00095-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du H, Puri S, McCall A, Norris HL, Russo T, Edgerton M. 2017. Human salivary protein histatin 5 has potent bactericidal activity against ESKAPE pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7:41. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tati S, Jang WS, Li R, Kumar R, Puri S, Edgerton M. 2013. Histatin 5 resistance of Candida glabrata can be reversed by insertion of Candida albicans polyamine transporter-encoding genes DUR3 and DUR31. PLoS One 8:e61480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang WS, Bajwa JS, Sun JN, Edgerton M. 2010. Salivary histatin 5 internalization by translocation, but not endocytosis, is required for fungicidal activity in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol 77:354–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. 2017. Emergence of Candida auris: an international call to arms. Clin Infect Dis 64:141–143. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S-C, Park Y, Hahm K-S. 2011. The role of antimicrobial peptides in preventing multidrug-resistant bacterial infections and biofilm formation. Int J Mol Sci 12:5971–5992. doi: 10.3390/ijms12095971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fitzgerald DH, Coleman DC, O'Connell BC. 2003. Susceptibility of Candida dubliniensis to salivary histatin 3. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:70–76. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.70-76.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghannoum MA, Rice LB. 1999. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 12:501–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brauer MJ, Huttenhower C, Airoldi EM, Rosenstein R, Matese JC, Gresham D, Boer VM, Troyanskaya OG, Botstein D. 2008. Coordination of growth rate, cell cycle, stress response, and metabolic activity in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 19:352–367. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shingu-Vazquez M, Traven A. 2011. Mitochondria and fungal pathogenesis: drug tolerance, virulence, and potential for antifungal therapy. Eukaryot Cell 10:1376–1383. doi: 10.1128/EC.05184-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borman AM, Szekely A, Johnson EM. 2016. Comparative pathogenicity of United Kingdom isolates of the emerging pathogen Candida auris and other key pathogenic Candida species. mSphere 1(4):e00189-. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00189-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H, Kohler J, Fink GR. 1994. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science 266:1723–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.7992058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edgerton M, Koshlukova SE, Lo TE, Chrzan BG, Straubinger RM, Raj PA. 1998. Candidacidal activity of salivary histatins. Identification of a histatin 5-binding protein on Candida albicans. J Biol Chem 273:20438–20447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayer FL, Wilson D, Jacobsen ID, Miramón P, Slesiona S, Bohovych IM, Brown AJ, Hube B. 2012. Small but crucial: the novel small heat shock protein Hsp21 mediates stress adaptation and virulence in Candida albicans. PLoS One 7:e38584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galán-Díez M, Arana DM, Serrano-Gómez D, Kremer L, Casasnovas JM, Ortega M, Cuesta-Domínguez Á, Corbí AL, Pla J, Fernández-Ruiz E. 2010. Candida albicans β-glucan exposure is controlled by the fungal CEK1-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway that modulates immune responses triggered through dectin-1. Infect Immun 78:1426–1436. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00989-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]