ABSTRACT

In our interest in oxabicyclic compounds as potent antileishmanial agents, the present work deals with the chemical synthesis of a new oxabicyclic derivative, methyl 4-(7-hydroxy-4,4,8-trimethyl-3-oxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-2-yl)benzoate (PS-207). This oxabicyclic derivative showed a good antileishmanial effect on the parasite, on both the promastigote and the amastigote. The mode of parasitic death from PS-207 seemed to be apoptosis-like. Interestingly, the combination of PS-207 with a low dose of miltefosine showed a synergistic effect against the parasite.

KEYWORDS: Leishmania donovani, miltefosine, drug development

TEXT

Leishmaniasis, caused by an intracellular dimorphic parasite, Leishmania, is one of the most neglected tropical diseases affecting millions of lives and has thus been a major concern worldwide. Leishmaniasis ranges from self-healing cutaneous leishmaniasis to life-threatening visceral leishmaniasis. Leishmania donovani is the causative agent of visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar). This severe clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis is responsible for the high mortality and morbidity rates in populations of the tropics and subtropics. If the patients are left untreated, it can be a fatal situation. Leishmaniasis is endemic infection in tropics and subtropics regions, found in 88 countries. Many countries, such as Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India, South Sudan, and Sudan, have observed over 90 percent of the cases of visceral leishmaniasis, the most fatal form of the disease. Approximately 0.2 to 0.4 million new cases are reported annually (1). Currently, the treatment of leishmaniasis is solely dependent on chemotherapy due to the unavailability of any successful vaccines against leishmaniasis (2). Furthermore, combinations of miltefosine with other drugs have been studied and were found to be very effective strategies (3–5). The current drug regimen used for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis comprises pentavalent antimonials, pentamidine, amphotericin B, paromomycin, and miltefosine. The limitations of these current chemotherapeutics provide a bottleneck for the treatment with great efficacy. The first line of drugs against the disease, pentavalent antimonials (sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate), are responsible for the rapid efflux of intracellular thiol trypanothione and the inhibition of trypanothione reductase, an enzyme necessary for the maintenance of redox metabolism in the parasite (6). These drugs are no longer in use due to their profound side effects, toxicity, and longer duration of treatment and the emergence of parasite resistance (7). The second-line drugs, pentamidine and amphotericin B, came into existence due to the low efficacy of antimony-based first-line drugs. However, these are more toxic and difficult to administer to patients. Pentamidine has been abandoned due to its toxicity and resistance in India (8). Amphotericin B acts as an antileishmanial drug by targeting ergosterol, an essential sterol found on the plasma membrane of Leishmania. Moreover, it also recognizes cholesterol in mammalian cells, which leads to high toxicity and severe side effects, including kidney failure, anemia, fever, and hypokalemia (9). The different formulations of amphotericin B, such as AmBisome, are also expensive, though its cure rate is high. The difficulty in the intravenous route of administration of the first- and second-choice antileishmanials adds to their limitations. Paromomycin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic, leads to alterations in membrane composition and fluidity (10). It has been found that a combinational approach with gentamicin resulted in increased efficacy for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis (11). In L. donovani, paromomycin is responsible for inhibiting protein synthesis through promoting the association of 50S and 30S subunits of both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ribosomes and hence preventing their recycling (12). The poor absorption of orally administered paromomycin limits its intramuscular route of administration. Resistance to this drug has been observed in vitro in L. donovani (13). Miltefosine, an alkylphospholipid, is the first orally administered antileishmanial drug. It is limited by its high cost, occasional hepatic and renal toxicity, and gastrointestinal side effects (14). Furthermore, miltefosine is an abortifacient and a potent teratogen and hence cannot be used as a treatment option for pregnant patients (15). Concurrently, miltefosine-unresponsive strains harbored in India confine its explicit usage.

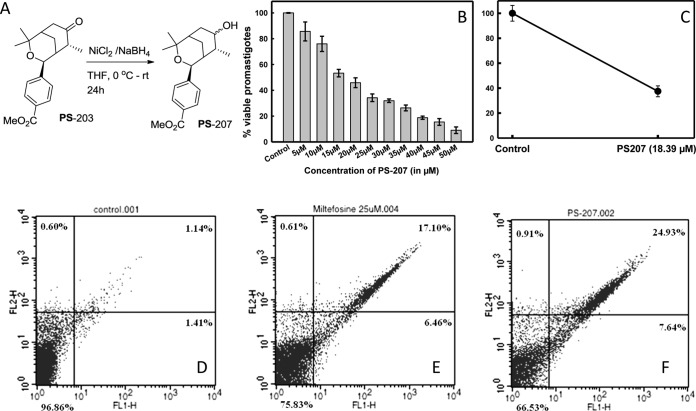

Such therapeutic complications accentuate the necessity to develop novel drug candidates to alleviate the disease. Likewise, the combination approach of the drugs can be considered a treatment option, since it leads to better efficacy and overcomes the limitation of drug resistance. Its cost-effectiveness and lesser time of treatment make it an attractive approach (4). One of the oxabicyclic compounds, 4-(4,4,8-trimethyl-7-oxo-3-oxabicyclo[3.3.1]non-2-yl)-benzoic acid methyl ester, designated PS-203, has been reported to be antileishmanial by our lab (16, 17). We hypothesized that several other oxabicyclic derivatives may also have antileishmanial activities with lower toxicities. These derivatives can provide new insights for the treatment of strains developing resistance against current therapeutics. In our interest in oxabicyclic compounds as potent antileishmanial agents, we synthesized a new oxabicyclic derivative, methyl 4-(7-hydroxy-4,4,8-trimethyl-3-oxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-2-yl)benzoate, as a diastereomeric mixture with a 3:2 ratio by selective reduction of the carbonyl group of PS-203 with NiCl2-NaBH4. The ratio of the isomers is determined by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The new synthesized compound is designated PS-207 for the simplicity of presentation. In this study, we evaluated the synthesized oxabicyclic compound for antileishmanial activity on both promastigote cells and amastigote cells. The cell viability of human macrophages was also investigated. We also observed the mode of death in the treated parasite. Furthermore, we tested the combination of PS-207 with 5 μM miltefosine against promastigote cells.

In vitro cell viability assay on L. donovani promastigote cells and human monocyte-derived macrophages.

Dose-dependent inhibition of PS-207 on L. donovani promastigote cells was observed (Fig. 1B). PS-207 showed a good antileishmanial effect, with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 18.39 ± 0.72 μM. The IC50 of PS-207 seems to be very good compared with those of other existing drugs, such as miltefosine, against the parasite. The literature shows that the IC50 of miltefosine is 25 μM (18), which is significantly higher than the PS-207 IC50. The compound PS-207 was further screened via an MTT [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] assay on human monocyte-derived macrophages to evaluate its safety. It showed no significant toxicity even at higher doses, and the IC50 on human monocyte-derived macrophages was found to be ∼100 μM (data not shown). This indicates the safety of the compound in limited doses.

FIG 1.

(A) Chemical synthesis of PS-207 from starting material 4-(4,4,8-trimethyl-7-oxo-3-oxabicyclo[3.3.1]non-2-yl)-benzoic acid methyl ester (PS-203) (16). (B) The effect of oxabicyclic derivative on L. donovani promastigote cells. The IC50 of PS-207 against L. donovani promastigote cells was 18.39 ± 0.72 μM. (C) The antileishmanial effect on the amastigote stage of the parasite was observed after counting the number of amastigote cells in treated human monocyte-derived macrophages. L. donovani amastigote cells were treated with an IC50 dose of PS-207 for 24 h. A total of 100 Giemsa-stained macrophages were counted manually for amastigotes in each cell. In comparison to the control, which was considered 100%, the percentage decrease in the number of amastigote cells in treated macrophages is shown. Flow cytometric analyses for mode of death in L. donovani promastigote cells treated with 0.2% DMSO for 24 h (control) (D), an IC50 dose of miltefosine for 24 h (positive control) (E), or an IC50 dose of PS-207 for 24 h (F) that were double stained with PI and annexin V-FITC.

Antileishmanial activity assay on amastigote cells.

The amastigote stage of the parasite in the macrophages was treated for 24 h with an IC50 dose of PS-207. The amastigote cells in 100 infected macrophages were counted manually after Giemsa staining, and the antileishmanial effect was observed. The percentage of amastigote cells in infected human macrophages after 24 h of treatment was plotted (Fig. 1C). We observed a considerable reduction in the percentage of amastigote cells in treated human macrophages in comparison to that in the control cells after 24 h.

Study on mode of death of L. donovani promastigote cells.

In PS-207-treated L. donovani promastigote cells, phosphatidyl serine externalization was studied using an apoptosis kit (Invitrogen) and analyzed by flow cytometry. L. donovani promastigote cells treated with either 0.2% dimethyl sulfoxide ([DMSO] negative control), an IC50 dose of miltefosine (positive control), or PS-207 were double stained with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI) to study the mode of death. In miltefosine- and PS-207-treated L. donovani promastigote cells, 6.46% and 7.64% of cells, respectively, were in early apoptotic stages (Fig. 1E and F), whereas only 1.41% of control cells were in an early apoptotic stage (Fig. 1D). In miltefosine- and PS-207-treated L. donovani promastigote cells, 17.10% and 24.93% of cells, respectively, were in late apoptotic stages (Fig. 1E and F), whereas only 1.14% of controls cells were in a late apoptotic stage (Fig. 1D). This demonstrates the apoptosis-like mode of death occurring in L. donovani promastigote cells after treatment with an IC50 dose of PS-207.

Effect of combination of PS-207 with 5 μM miltefosine on L. donovani promastigote cells.

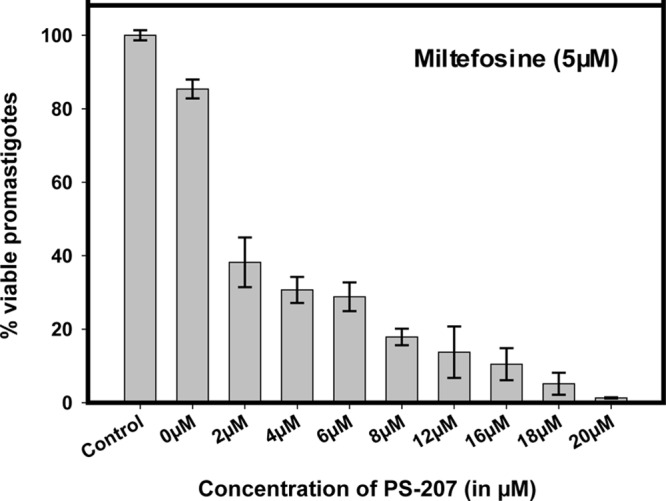

The synergistic effect of the combination of PS-207 with 5 μM miltefosine was observed on L. donovani promastigote cells via an in vitro cell viability assay (MTT assay). The combination of various concentrations of PS-207 with 5 μM miltefosine showed an improved efficacy of the compound, with an IC50 of 1.50 ± 0.25 μM (Fig. 2). The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index for the combination was found to be 0.088, which depicted the synergistic effect of the two compounds. The better antileishmanial effect with a higher efficacy of the combination can lead to a lower dosage requirement and less toxicity. Therefore, the combination approach of PS-207 with miltefosine can provide new insights for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis.

FIG 2.

Effect of combination of PS-207 with 5 μM miltefosine on L. donovani promastigote cells. L. donovani promastigote cells were treated with different concentrations of PS-207 in combination with 5 μM miltefosine for 24 h. The untreated promastigote cells were used as the control. The IC50 of PS-207 against promastigote cells was 1.50 ± 0.25 μM in combination with 5 μM miltefosine.

New oxabicyclic derivative PS-207 was synthesized and characterized using proton (1H) and carbon (13C) NMR spectroscopy, infrared (IR) spectroscopy, and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS). The in vitro cell viability assay on L. donovani promastigote cells showed that the PS-207 (IC50, 18.39 ± 0.72 μM) oxabicyclic compound has a better antileishmanial effect. Further screening of the PS-207 oxabicyclic compound with an in vitro cell viability assay on human monocyte-derived macrophages showed a less toxic effect of PS-207 compared to that of the existing drug. These findings suggest that a lower dose of the PS-207 compound can be utilized for selective inhibition of the parasite. The low IC50 and reduced toxicity of PS-207 with human monocyte-derived macrophages compared with those of miltefosine demonstrate that it may be a potential drug candidate against miltefosine-responsive and -unresponsive Leishmania parasites in the future. We used flow cytometry to study the mode of death of L. donovani promastigote cells after treatment with an IC50 dose of PS-207 and found it to be an apoptosis-like cell death. We compared the percentages of apoptotic parasites treated with miltefosine or PS-207 and found that a greater percentage of cells treated with PS-207 were in a late apoptotic stage. To observe the effect on the amastigote cells, we carried out an antileishmanial activity assay, which showed a considerable decrease in the percentage of amastigote cells after 24 h of treatment with an IC50 dose of PS-207. As the emergence of unresponsiveness toward miltefosine can be detrimental for alleviating the deadly parasitic disease, we also utilized the combination therapy of PS-207 with a low dose of miltefosine. The observance of the apoptosis-like mode of cell death with good efficacy by both the drugs PS-207 and miltefosine is one of the main reasons to perform combination treatment to know its synergistic effects. The combinational approach of PS-207 with 5 μM miltefosine showed an improved efficacy of the compound against L. donovani promastigote cells. The report is available in the literature about miltefosine cytotoxicity, and investigators showed that their 50% effective concentration ([EC50] 13.77 ± 10 μM) with human macrophages is quite high (19). So, the utilization of combination therapies will be the better choice to reduce their toxic effects. The IC50 of PS-207 against promastigote cells when it was used in combination with 5 μM miltefosine was found to be 1.50 ± 0.25 μM. This IC50 was found to be much lower than the individual IC50s of PS-207 and miltefosine. We found that there is a synergistic effect of the combination with an FIC index of 0.088 on the parasite.

Parasites, cell line, and chemicals.

Leishmania donovani (MHOM/IN/2010/BHU1081) was obtained from Shyam Sundar, Banaras Hindu University, India. The human monocyte cell line U937 was obtained from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India. The apoptosis detection kit was procured from Invitrogen. All the chemicals for cell culture were of the highest grade and were procured from Sigma-Aldrich or Merck.

Parasite cultures and maintenance of host cells.

Leishmania donovani (MHOM/IN/2010/BHU1081) cells were cultivated at 25°C in M199 medium supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U · ml−1 penicillin, and 100 μg · ml−1 streptomycin, as reported earlier (20). The human monocyte cell line U937 was cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 10,000 U · ml−1 penicillin, 10 mg · ml−1 streptomycin sulfate, and 25 μg · ml−1 amphotericin B.

Chemical synthesis of methyl 4-(7-hydroxy-4,4,8-trimethyl-3-oxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonan-2-yl)benzoate.

Dry tetrahydrofuran ([THF] 5 ml) was added to a mixture of NiCl2 (1.9 g, 15 mmol, 3.0 eq) and NaBH4 (1.75 g, 45 mmol, 9 eq) at 0°C, and the formation of a black precipitate of nickel boride was observed immediately. To this suspension, a solution of 4-(4,4,8-trimethyl-7-oxo-3-oxabicyclo[3.3.1]non-2-yl)-benzoic acid methyl ester ([PS-203] 1.5g, 5 mmol, 1.0 eq) in dry THF (5 ml) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The reaction mixture was then diluted with ethyl acetate (100 ml) and filtered through a Celite pad. The solvent was then concentrated in vacuo, and the crude product was purified using column chromatography with ethyl acetate and hexane (1:9) as eluents to give the title compound as a diastereomeric mixture with a ratio of 3:2 PS-207 (636 mg [40%]) as a pale yellow solid; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 1.06 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 3-H), 1.31 (s, 3-H), 1.41 (s, 3-H), 1.95 to 1.97 (m, 2-H), 2.15 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 1-H), 2.26 (dd, J = 4.4 and 15.6 Hz, 1-H), 2.35 (dd, J = 4.8 and 15.6 Hz, 1-H), 2.47 (dd, J = 4.4 and 14.8 Hz, 1-H), 2.61 (dd, J = 5.2 and 14.8 Hz, 1-H), 3.43 (dt, J = 4.8 and 17.6 Hz, 1-H, major), 3.59 (dt, J = 6.4 and J = 12.4 Hz, 1-H, minor), 3.90 (s, 4-H), 4.96 (s, 1-H), 7.32 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2-H), 7.99 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2-H); 13C NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 19.9, 24.1, 25.3, 28.0, 31.3, 34.9, 35.5, 39.5, 52.2, 70.2, 75.6, 76.6, 125.3, 128.7, 129.8, 146.2, 167.2; IR (KBr, neat) 3437, 2950, 2900, 1722, 1612, 1435, 1410, 1381, 1280, 1155, 1069, 1041, 764, 715 cm−1; HRMS (APCI) calculated for C19H27O4 (M + H)+ requires 319.1904 (found, 319.1903). Compound purity and structure validation was confirmed through IR, 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry.

In vitro cell viability assay on L. donovani promastigote cells and human monocyte-derived macrophages.

The in vitro cell viability of L. donovani promastigote cells and human monocyte-derived macrophages was investigated by using the MTT assay, a colorimetric cell proliferation assay (16, 21). Human monocyte U937 cells were made adherent macrophages using phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) at the concentration of 100 ng/ml at 37°C in 5% CO2 overnight (22). In brief, L. donovani promastigote cells (2.5 × 106 cells/ml) and human macrophages (104 cells/ml) were treated with increasing concentrations of the oxabicyclic compound for 24 h at 25°C and 37°C, respectively, in 5% CO2. The promastigote cells treated with 0.2% DMSO were used as a negative control, whereas the 25 μM IC50 of miltefosine (18) was used as a positive control. After incubating, MTT dye (0.5 mg/ml) was added, and cells were further incubated for 4 h in the dark at 25°C and then centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 45 min. The visible pellets (purple formazan product) were dissolved in DMSO, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm on a microtiter plate reader (BioTek Synergy HT).

Study on mode of death of L. donovani promastigote cells.

The mode of death in L. donovani promastigote cells was studied using a FITC annexin V/dead cell apoptosis kit with FITC annexin V and PI for flow cytometry (Invitrogen) as per the instructions given by the manufacturer and the procedure reported in our earlier publications (16, 20).

Antileishmanial activity assay on amastigote cells.

The human monocyte U937 cells were made adherent using 100 ng/ml PMA for 24 h. Then, the medium was discarded and adherent cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, fresh medium was added to prepare the cells for parasite infection. Subsequently, the macrophages were infected for 24 h with L. donovani promastigote cells by maintaining the ratio of promastigote cells to macrophages as 10:1. The infected macrophages were then treated with an IC50 dose of PS-207 for 24 h. The infected macrophages that were not treated with the compound were used as the control. After incubating, the cells were fixed with methanol and were Giemsa stained. The numbers of intracellular amastigotes were counted by microscopy of 100 randomly chosen infected macrophages. The parasite density in treated macrophages was expressed as a percentage of the control.

Effect of combination of PS-207 with 5 μM miltefosine on L. donovani promastigote cells.

The effect of PS-207 in combination with 5 μM (low dose) miltefosine was evaluated on L. donovani promastigote cells by using an in vitro cell viability assay (MTT assay), and the IC50 of PS-207 in combination with 5 μM miltefosine was calculated. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index was calculated using the following formula: FIC index = [A]/IC50A + [B]/IC50B, where IC50A and IC50B are the IC50s of miltefosine and PS-207, respectively, when tested alone, and [A] and [B] are the IC50s of the miltefosine or PS-207 when treatment was carried out in combination. An FIC index of <0.5 indicates synergy, while an index of >4 indicates antagonism and an index between 0.5 and 4 indicates indifference (23, 24).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Infrastructural facilities were provided by the Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati.

This work was supported by funds from the Department of Biotechnology (project no. BT/PR12260/MED/29/889/2014) and a research grant to V.K.D. and A.K.S. from the Government of India. P.B., S.S., and A.K.C. were supported by research fellowships from the Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvar J, Velez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, Jannin J, den Boer M, WHO Leishmaniasis Control Team. 2012. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One 7:e35671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Handman E. 2001. Leishmaniasis: current status of vaccine development. Clin Microbiol Rev 14:229–243. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.229-243.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meheus F, Balasegaram M, Olliaro P, Sundar S, Rijal S, Faiz MA, Boelaert M. 2010. Cost-effectiveness analysis of combination therapies for visceral leishmaniasis in the Indian subcontinent. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4:e818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Griensven J, Balasegaram M, Meheus F, Alvar J, Lynen L, Boelaert M. 2010. Combination therapy for visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet Infect Dis 10:184–194. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das M, Saha G, Saikia AK, Dubey VK. 2015. Novel agents against miltefosine-unresponsive Leishmania donovani. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:7826–7829. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00928-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyllie S, Cunningham ML, Fairlamb AH. 2004. Dual action of antimonial drugs on thiol redox metabolism in the human pathogen Leishmania donovani. J Biol Chem 279:39925–39932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray HW. 2001. Clinical and experimental advances in treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:2185–2197. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.8.2185-2197.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sundar S. 2001. Drug resistance in Indian visceral leishmaniasis. Trop Med Int Health 6:849–854. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachaud L, Bourgeois N, Plourde M, Leprohon P, Bastien P, Ouellette M. 2009. Parasite susceptibility to amphotericin B in failures of treatment for visceral leishmaniasis in patients coinfected with HIV type 1 and Leishmania infantum. Clin Infect Dis 48:e16–e22. doi: 10.1086/595710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maarouf M, Lawrence F, Brown S, Robert-Gero M. 1997. Biochemical alterations in paromomycin-treated Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Parasitol Res 83:198–202. doi: 10.1007/s004360050232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben Salah A, Buffet PA, Morizot G, Ben Massoud N, Zaatour A, Ben Alaya N, Haj Hamida NB, El Ahmadi Z, Downs MT, Smith PL, Dellagi K, Grögl M. 2009. WR279,396, a third generation aminoglycoside ointment for the treatment of Leishmania major cutaneous leishmaniasis: a phase 2, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3:e432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maarouf M, Lawrence F, Croft SL, Robert-Gero M. 1995. Ribosomes of Leishmania are a target for the aminoglycosides. Parasitol Res 81:421–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00931504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jhingran A, Chawla B, Saxena S, Barrett MP, Madhubala R. 2009. Paromomycin: uptake and resistance in Leishmania donovani. Mol Biochem Parasitol 164:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundar S, Singh A, Rai M, Prajapati VK, Singh AK, Ostyn B, Boelaert M, Dujardin JC, Chakravarty J. 2012. Efficacy of miltefosine in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in India after a decade of use. Clin Infect Dis 55:543–550. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh N, Kumar M, Singh RK. 2012. Leishmaniasis: current status of available drugs and new potential drug targets. Asian Pac J Trop Med 5:485–497. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saudagar P, Saha P, Saikia AK, Dubey VK. 2013. Molecular mechanism underlying antileishmanial effect of oxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanones: inhibition of key redox enzymes of the pathogen. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 85:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saudagar P, Mudavath SL, Saha P, Saikia AK, Sundar S, Dubey VK. 2014. In vivo assessment of antileishmanial property of 4-(4,4,8-trimethyl-7-oxo-3-oxabicyclo[3.3.1]non-2-yl)-benzoic acid methyl ester, an oxabicyclo[3.3.1]nonanones. Lett Drug Des Discov 11:937–939. doi: 10.2174/1570180811666140423203826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verma NK, Dey CS. 2004. Possible mechanism of miltefosine-mediated death of Leishmania donovani. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:3010–3015. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3010-3015.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta SR, Zhang XQ, Badaro R, Spina C, Day J, Chang KP, Schooley RT. 2010. Flow cytometric screening for anti-leishmanials in a human macrophage cell line. Exp Parasitol 126:617–620. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar R, Tiwari K, Dubey VK. 2017. Methionine aminopeptidase 2 is a key regulator of apoptotic like cell death in Leishmania donovani. Sci Rep 7:95. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00186-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosmann T. 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takashiba S, Van Dyke TE, Amar S, Murayama Y, Soskolne AW, Shapira L. 1999. Differentiation of monocytes to macrophages primes cells for lipopolysaccharide stimulation via accumulation of cytoplasmic nuclear factor kappaB. Infect Immun 67:5573–5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Morais-Teixeira E, Gallupo MK, Rodrigues LF, Romanha AJ, Rabello A. 2014. In vitro interaction between paromomycin sulphate and four drugs with leishmanicidal activity against three New World Leishmania species. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:150–154. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pastor J, García M, Steinbauer S, Setzer WN, Scull R, Gille L, Monzote L. 2015. Combinations of ascaridole, carvacrol, and caryophyllene oxide against Leishmania. Acta Trop 145:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]