Abstract

Background

Accurate determination of right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) is challenging because of the unique geometry of the right ventricle. Tricuspidannular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) and fractional area change (FAC) are commonly used echocardiographic quantitative estimates of RV function. Cardiac MRI (CMRI) has emerged as the gold standard for assessment of RVEF. We sought to summarise the available data on correlation of TAPSE and FAC with CMRI-derived RVEF and to compare their accuracy.

Methods

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov and the Cochrane Library databases for studies that assessed the correlation of TAPSE or FAC with CMRI-derived RVEF. Data from each study selected were pooled and analysed to compare the correlation coefficient of TAPSE and FAC with CMRI-derived RVEF. Subgroup analysis was performed on patients with pulmonary hypertension.

Results

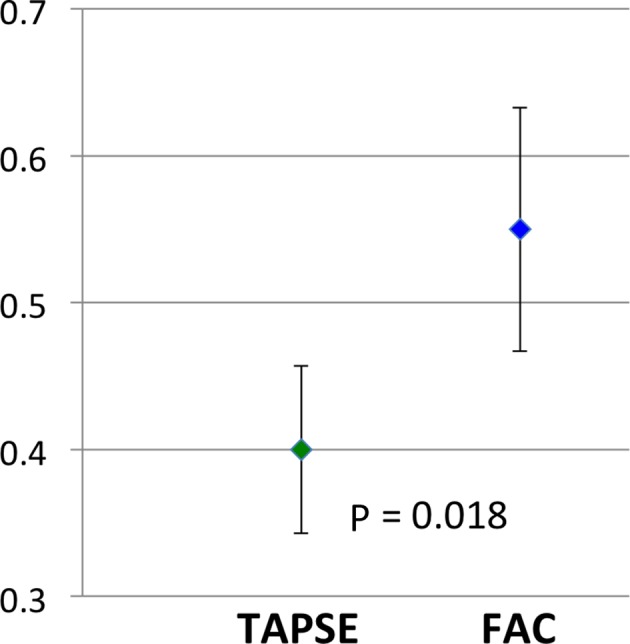

Analysis of data from 17 studies with a total of 1280 patients revealed that FAC had a higher correlation with CMRI-derived RVEF compared with TAPSE (0.56vs0.40, P=0.018). In patients with pulmonary hypertension, there was no statistical difference in the mean correlation coefficient of FAC and TAPSE to CMR (0.57vs0.46, P=0.16).

Conclusions

FAC provides a more accurate estimate of RV systolic function (RVSF) compared with TAPSE. Adoption of FAC as a routine tool for the assessment of RVSF should be considered, especially since it is also an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality. Further studies will be needed to compare other methods of echocardiographic measurement of RV function.

Keywords: transthoracic, systolic dysfunction, echocardiography

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) and fractional area change (FAC) are commonly used echocardiographic quantitative estimates of right ventricular (RV) function. There has yet to be a systematic overview that would provide a more precise estimate of the accuracy of TAPSE and FAC in their assessment of RV systolic function (RVSF).

What does this study add?

Systematic analysis of 17 studies revealed that FAC had a higher correlation with cardiac MRI-derived RV ejection fraction compared with TAPSE.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Adoption of FAC as a routine tool for the assessment of RVSF should be considered and should be performed in addition to TAPSE when possible.

Introduction

Right ventricular (RV) function is an important predictor of outcome in a variety of cardiovascular diseases and therefore, a precise evaluation of RV function is essential.1–3 However, the unique geometry of the right ventricle poses difficulty in volume and hence ejection fraction assessments by two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography, in both normal and disease states. An accurate evaluation of RV function remains challenging in clinical practice, due to the absence of any widely accepted 2D echocardiographic methods to assess RV systolic function (RVSF).

Traditional echocardiographic surrogates of RV ejection fraction (RVEF) include tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) and fractional area change (FAC). TAPSE is a one-dimensional measure of RVSF and assumes that the displacement of basal and adjacent segments of the RV represents the entire RV function. By contrast, FAC is a 2D parameter. There have been multiple studies evaluating the accuracy of various 2D echocardiographic parameters by comparing them with the gold standard, cardiac MRI (CMRI)-derived RVEF. However, studies are limited by their small sample size. There has yet to be a systematic overview that would provide a more precise estimate of the accuracy of TAPSE and FAC in their assessment of RVSF. In our study, we aim to summarise available data on TAPSE and FAC and compare their accuracy in the measurement of RV function.

Methods

A systematic literature review was planned and performed using methods specified in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic review.4 Both controlled vocabulary terms (eg, MeSH) and key words were used to search for articles comparing TAPSE and FAC to CMRI-derived RVEF. The following databases were searched:

Ovid/MEDLINE (1946–2016); Elsevier/EMBASE (1947–2016); Wiley/Cochrane Library (1898 −2016); Thomson-Reuters/Web of Science (1898–2016); and ClinicalTrials.gov (1997–2016).

Literature searches were completed on 18 April 2016. The complete Ovid/MEDLINE search strategy, analogous to the other database searches, is available in appendix A.

openhrt-2017-000667supp001.docx (15.9KB, docx)

No publication date or language limit was applied.

Study selection

Studies were considered eligible if they assessed RVSF with TAPSE or FAC derived from 2D echocardiography and RVEF derived from CMRI. Our prespecified selection criteria were as follows1: studies with patients undergoing both 2D echocardiography and CMRI,2 TAPSE, FAC data and CMRI-derived RVEF obtained in the same patient,3 human studies. We did not limit the scope of indications for echocardiography and CMRI to be included in our meta-analysis. Exclusion criteria were1: studies based on congenital heart disease,2 case reports, review articles, commentaries and editorials. Two independent reviewers performed the study selection (JL, SL). In case of disagreements, a third reviewer (AP) cast the deciding vote. Titles and abstracts of retrieved references were screened for inclusion and full texts of potential articles were further analysed to see if they met inclusion criteria (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection diagram.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted from each study: study name, study authors, year of publication, type of manuscript and demographic profiles including number of subject, background disease, median age and gender. We also extracted mean TAPSE, mean FAC, mean CMRI-derived RVEF, TAPSE correlation coefficient with CMRI-derived RVEF and FAC correlation coefficient with CMRI-derived RVEF and P values from each study.

Statistical analysis

Mean TAPSE and FAC to CMRI-derived RVEF correlation coefficient from each study were weighted based on number of patients in each study relative to the total number of patients. Paired Student t-test analysis was used as comparison data were obtained from the same patient in each study. Mean difference of mean correlation coefficients was calculated. Similar statistical methodology was used to perform subgroup analyses of patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH). We used IBM SPSS Statistics (V.22 for Windows) for the calculation of paired Student t-test.

Results

We found 7450 articles through database searching. Of the 5283 articles that remained after duplicates were removed, 4990 were excluded due to irrelevance to the topic (figure 1). Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria as outlined above were applied to the full text of 293 articles. Of these, 17 prospective and retrospective studies met full criteria and when combined for this meta-analysis included 1280 patients.

Study characteristics

Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of included studies. The 17 studies comprised 10 full papers5–14 and 7 abstracts.15–21 There was a mixture of prospective and retrospective studies. The pooled patient population included healthy patients as well as patients with idiopathic cardiomyopathy, ischaemic heart disease, PH and end-stage lung disease. The mean age was 51±9 years with men accounting for 54% of subjects. In each included study, patients underwent 2D echocardiogram and had both TAPSE and FAC measured. This was followed by CMRI with measurement of RVEF.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| No | Author | Year | Type of manuscript | Number of patients | Patient population | Mean age (year) | Man, % | TAPSE EF (mm) | TAPSE correlation coefficient | P value for TAPSE | FAC EF (%) | FAC correlation coefficient | P value | CMR RVEF (%) |

| 1. | Anavekar et al | 2007 | Paper | 36 | Patient undergoing assessment of ischaemia or viability | 59±12 | 63 | NA | 0.17 | <0.30 | NA | 0.8 | <0.0001 | 55±8.9 |

| 2. | Arnould et al | 2009 | Paper | 19 | Mixed population with EF ≤45% | NA | NA | 18.8±5.7 | 0.472 | 0.006 | 33±11 | 0.684 | 0.000 | 29.53±10.29 |

| 13 | Mixed population with EF >45% | NA | NA | 21.2±5.1 | 0.006 | 47±8 | 0.000 | 55.6±5.4 | ||||||

| 3. | Chen et al | 2011 | Abstract | 60 | All clinical patients referred for CMR also underwent echocardiography | 45 | 60 | NA | 0.48 | 0.01 | NA | 0.56 | <0.001 | 50% |

| 4. | Focardi et al | 2015 | Paper | 63 | Mixed population with RVEF ≤45% | 46±17 | 49 | 18.2±4.4 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 42.2±11 | 0.77 | <0.0001 | 40.1±4.8 |

| Mixed population with RVEF> 45% | 43±17 | 48 | 23.2±4.6 | NA | NA | 55.4±11 | NA | NA | 58.8±8.2 | |||||

| 5. | Freed et al | 2012 | Abstract | 25 | PAH | NA | NA | NA | 0.47 | NA | NA | 0.63 | NA | 35±14 |

| 6. | Grover et al | 2011 | Abstract | 90 | Mixed population | 61 | NA | NA | 0.65 | <0.001 | NA | 0.53 | 0.002 | NA |

| 7. | Lemarie et al | 2015 | Paper | 135 | AMI | 55±11 | 87 | 21.8±4.5 | 0.267 | 0.002 | 43.8±9.6 | 0.368 | <0.0001 | 54.8±6.2 |

| 8. | Li et al | 2015 | Paper | 32 | CTEPH | 55±12 | 53 | 13.74±2.29 | 0.451 | 0.22 | 29.9±9.01 | 0.423 | 0.022 | 39±9 |

| 9. | Maceira Gonzales et al | 2010 | Abstract | 40 | Mixed population | NA | NA | NA | 0.80 | >0.001 | NA | 0.76 | >0.001 | NA |

| 10. | Pavlicek et al | 2011 | Paper | 129 | RVEF ≥50% | 44±19 | 70 | 20±6 | 0.34 | <0.0001 | 41±13 | 0.47 | <0.0001 | 61±7 |

| 67 | RVEF >30%–49% | 41±18 | 66 | 17±6 | 33±11 | 44±3 | ||||||||

| 27 | RVEF ≤30% | 53±20 | 85 | 13±5 | 23±8 | 28±2 | ||||||||

| 11. | Renard et al | 2014 | Abstract | 61 | PH | 57±16 | 47 | NA | 0.48 | NA | NA | 0.51 | NA | NA |

| 12. | Sato et al | 2012 | Paper | 37 | PAH | 53±15 | 30 | 19±4 | 0.86 | NA | 31±17 | 0.4 | NA | 38±11 |

| 13. | Shiran et al | 2O14 | Paper | 40 | PAH | 42±12 | 15 | NA | 0.8 | <0.001 | NA | 0.87 | <0.001 | 35±15 |

| 14. | Spruijt et al | 2017 | Paper | 96 | PH | 53±16 | 28 | 18.8±4 | 0.485 | NA | 35.8±11.4 | 0.753 | NA | 41.4±15.2 |

| 15. | Takemoto et al | 2015 | Abstract | 142 | NA | 55±18 | 54 | NA | 0.22 | 0.0121 | NA | 0.596 | <0.0001 | NA |

| 16. | Yang et al | 2013 | Paper | 30 | PAH | 30±10 | 20 | 16.3±2.7 | 0.440 | 0.015 | 28.9±7.0 | 0.416 | 0.022 | 27±12 |

| 17. | Zhou et al | 2015 | Abstract | 125 | NA | 55±16 | 51 | 19.6±5.4 | 0.12 | 0.4 | 42.9±9.1 | 0.43 | 0.003 | 53.6±11.6 |

CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CTEPH, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; EF, ejection fraction; FAC, fractional area change; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; PH, pulmonary hypertension; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Comparison of TAPSE and FAC

Composite mean correlation coefficient from each study revealed that FAC had a higher mean correlation coefficient (r) of 0.56 (SE of 0.08) compared with TAPSE, which had a mean correlation coefficient (r) of 0.40 (SE of 0.06) (figure 2). This difference was statistically significant (P=0.018).

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean correlation coefficient in TAPSE and FAC. FAC, fractional area change; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Pulmonary hypertension

Pooled data from 321 patients with PH revealed that TAPSE had a mean correlation coefficient of 0.46 (SE of 0.07) and FAC had a mean correlation coefficient of 0.57 (SE of 0.12) (figure 3). This difference was not statistically significant (P=0.16).

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean correlation coefficient in TAPSE and FAC in PH. FAC, fractional area change; PH, pulmonary hypertension;TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis involving 1280 patients from 17 studies revealed the following findings:

(1) overall analysis revealed FAC to have significantly higher correlation with CMRI-derived RVEF compared with TAPSE; (2) in patients with PH, both TAPSE and FAC had similar correlation with CMRI-derived RVEF.

The right ventricle has a complex geometry. It is triangular when viewed from the side and crescentic when viewed in cross-section.22 Anatomically, the RV can be subdivided into three parts; an inlet portion, a highly trabeculated body and a smooth outlet portion, known as the conus or infundibulum. RVSF can be assessed using 2D echocardiography by various direct and indirect measurements.23 Direct measurements include TAPSE; systolic velocity (s’) as measured by tissue Doppler imaging; FAC measured by tracing the area during systole and diastole; and RV index of myocardial performance, where both systolic and diastolic components are included. Indirect measurements include relative volumes of RV and LV; degree of septal flattening; angle created at the RV apex24; and various Doppler indices such as RV dP/dT and tricuspid regurgitation duration indexed to heart rate.25 In our study, we compared TAPSE, a simple and common method of measuring RVSF, with FAC, one of the better 2D echocardiographic methods of assessing RVSF.5 CMRI is regarded as the reference method for assessing RV function and has been shown to have good correlation with in vivo standards, with good accuracy and reproducibility.26 27

Our overall pooled analysis revealed FAC to be a more accurate measurement of RVEF compared with TAPSE. This is likely because TAPSE is a one-dimensional measurement, whereas FAC is a 2D measurement. In situations where there are regional differences in the RV function, TAPSE does not always provide accurate information due to the fact that it disregards the transverse contribution of RV free wall and septum. TAPSE was also noted to be markedly depressed after cardiac surgery when three-dimensional echo showed preserved RVEF, suggesting that it is affected by postoperative changes in the geometry of RV contraction.28 29 FAC, in addition to including the longitudinal shortening fraction, also incorporates the changes that occur in the transverse plane. In situations where regional differences in RV function are noted, FAC may provide better estimates. A study by Sakuma et al using cineangiography to assess RVEF revealed a significant contribution of transverse systolic shortening to RVEF.30

Our study also found that in patients with PH, no significant difference was found between TAPSE and FAC. This is likely because the longitudinal component of RV contraction represents the afterload-responsive element of RV function.31 This is measured in both TAPSE and FAC and therefore, there may not be a difference between their accuracy of measurement of RVSF among patients with PH. A prior study has also suggested that pseudo-normalisation of TAPSE may occur in PH due emergence of a ‘rocking’ pattern from compression of a pressure-loaded right heart on a compliant left heart.32 The systolic function of this ‘rocking’ right ventricle may be better analysed using speckle-tracking echocardiography, as opposed to translational parameters such as TAPSE or velocity of the tricuspid annular systolic motion (RV S’).

Compared with TAPSE, FAC may require a better image quality of the right ventricle in order to trace the RV endocardium to calculate FAC. However, this should not be a reason to deter the use of FAC, as it is a more accurate assessment of RVEF. More studies will have to be done to determine the intraobserver and interobserver variabilities of the use of TAPSE and FAC and its impact on accuracy. RV FAC has also been found to be an independent predictor of heart failure, sudden death, stroke and mortality.1–3 This provides significant justification for the usage of FAC as a reliable surrogate of RVSF.

Limitations

This meta-analysis is based on extrapolated data from multiple studies. We were not able to obtain individual patient level data from each study. Abstracts were also included in our study in order to avoid publication bias. However, the limitation of inclusion of abstracts is that they receive less editorial scrutiny and may have been vetted less when compared with a full paper publication. Another limitation is the possible variability in time delay from echocardiogram to MRI. However, although the exact time between echocardiogram to MRI was not reported, each study only included patients who were in stable clinical condition and therefore, significant variation of RV function between imaging periods were not expected. Another potential limitation is that there may be interstudy and intrastudy variability that may affect the conclusion of our analysis. Lastly, the percentage of uninterpretable images due to poor imaging quality were not reported in some studies and could not be included in the analysis.

Conclusion

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that FAC provides a more accurate estimate of RVSF compared with TAPSE. Adoption of FAC as a routine tool for the assessment of RVSF should be considered, especially since it is also an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality. Further studies will be needed to compare other echocardiographic measurements of RVEF.

Footnotes

Contributors: JZL: drafting of manuscript, literature screening and statistical analysis. SWL: collection of data and literature screening. AKP: drafting of manuscript and literature screening. CLH: literature search. KSL: revising critically for important intellectual content. PGS: drafting of manuscript, revising critically for important intellectual content and final approval of manuscript submitted.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Zornoff LA, Skali H, Pfeffer MA, et al. . Right ventricular dysfunction and risk of heart failure and mortality after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1450–5. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01804-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anavekar NS, Skali H, Bourgoun M, et al. . Usefulness of right ventricular fractional area change to predict death, heart failure, and stroke following myocardial infarction (from the VALIANT ECHO Study). Am J Cardiol 2008;101:607–12. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.09.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nass N, McConnell MV, Goldhaber SZ, et al. . Recovery of regional right ventricular function after thrombolysis for pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol 1999;83:804–6. 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)01000-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anavekar NS, Gerson D, Skali H, et al. . Two-dimensional assessment of right ventricular function: an echocardiographic-MRI correlative study. Echocardiography 2007;24:452–6. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00424.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arnould MA, Gougnot S, Lemoine S, et al. . Quantification of right ventricular function by 2D speckle imaging: Comparison with MRI. Eur Heart J 2009;30:56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Focardi M, Cameli M, Carbone SF, et al. . Traditional and innovative echocardiographic parameters for the analysis of right ventricular performance in comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:47–52. 10.1093/ehjci/jeu156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lemarié J, Huttin O, Girerd N, et al. . Usefulness of speckle-tracking imaging for right ventricular assessment after acute myocardial infarction: a magnetic resonance imaging/echocardiographic comparison within the relation between aldosterone and cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:818–27. 10.1016/j.echo.2015.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li YD, Wang YD, Zhai ZG, et al. . Relationship between echocardiographic and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging-derived measures of right ventricular function in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Thromb Res 2015;135:602–6. 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pavlicek M, Wahl A, Rutz T, et al. . Right ventricular systolic function assessment: rank of echocardiographic methods vs. cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Echocardiogr 2011;12:871–80. 10.1093/ejechocard/jer138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sato T, Tsujino I, Ohira H, et al. . Validation study on the accuracy of echocardiographic measurements of right ventricular systolic function in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2012;25:280–6. 10.1016/j.echo.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shiran H, Zamanian RT, McConnell MV, et al. . Relationship between echocardiographic and magnetic resonance derived measures of right ventricular size and function in patients with pulmonary hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2014;27:405–12. 10.1016/j.echo.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spruijt OA, Di Pasqua MC, Bogaard HJ, et al. . Serial assessment of right ventricular systolic function in patients with precapillary pulmonary hypertension using simple echocardiographic parameters: a comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiol 2017;69:182–8. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2016.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang T, Liang Y, Zhang Y, et al. . Echocardiographic parameters in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: correlations with right ventricular ejection fraction derived from cardiac magnetic resonance and hemodynamics. PLoS One 2013;8:e71276 10.1371/journal.pone.0071276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen J, Profitis K, Lu K, et al. . Evaluation of right ventricular volume and systolic function – a comparison of 2 and 3-dimensional echocardiography with cardiac magnetic resonance. Heart, Lung and Circulation 2011;20:S5 10.1016/j.hlc.2011.05.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freed BH, Bhave NM, Tsang W, et al. . Multi-modality comparison of ase guideline echocardiographic parameters to assess right ventricular function in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2012;25:B116. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grover SK, Leong DP, Molaee P, et al. . Validation of echocardiographic indices of right ventriclular systolic function with cardiac magnetic resonance: a comparative study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2011;13:75 10.1186/1532-429X-13-S1-O75 22123333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maceira Gonzalez AM, Cosin-Sales J, Dalli E, et al. . Which are the best echocardiographic predictors of right ventricular systolic dysfunction? Assessment with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;11:ii135. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Renard S, Najih H, Mancini J, et al. . Assessment and prognostic value of right ventricular dysfunction in precapillary pulmonary hypertension. Comparison between speckle tracking imaging and MRI-derived RV ejection fraction. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;15:ii31. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takemoto R, Oe H, Ohno Y, et al. . The impact of significant tricuspid regurgitation on echocardiographic assessment of right ventricular performance. Eur Heart J 2015;36:603. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou X, Liu S, Qian Z, et al. . Comparison of conventional echocardiographic parameters of RV systolic function with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015;17:M10 10.1186/1532-429X-17-S1-M10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. James TN. Anatomy of the crista supraventricularis: its importance for understanding right ventricular function, right ventricular infarction and related conditions. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;6:1083–95. 10.1016/S0735-1097(85)80313-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. . Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:685–713. quiz 86-8 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. López-Candales A, Dohi K, Iliescu A, et al. . An abnormal right ventricular apical angle is indicative of global right ventricular impairment. Echocardiography 2006;23:361–8. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2006.00237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cho IJ, Oh J, Chang HJ, et al. . Tricuspid regurgitation duration correlates with cardiovascular magnetic resonance-derived right ventricular ejection fraction and predict prognosis in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;15:18–23. 10.1093/ehjci/jet094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grothues F, Moon JC, Bellenger NG, et al. . Interstudy reproducibility of right ventricular volumes, function, and mass with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am Heart J 2004;147:218–23. 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Møgelvang J, Stubgaard M, Thomsen C, et al. . Evaluation of right ventricular volumes measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J 1988;9:529–33. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maffessanti F, Gripari P, Tamborini G, et al. . Evaluation of right ventricular systolic function after mitral valve repair: a two-dimensional Doppler, speckle-tracking, and three-dimensional echocardiographic study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2012;25:701–8. 10.1016/j.echo.2012.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tamborini G, Muratori M, Brusoni D, et al. . Is right ventricular systolic function reduced after cardiac surgery? A two- and three-dimensional echocardiographic study. Eur J Echocardiogr 2009;10:630–4. 10.1093/ejechocard/jep015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sakuma M, Ishigaki H, Komaki K, et al. . Right ventricular ejection function assessed by cineangiography–Importance of bellows action. Circ J 2002;66:605–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brown SB, Raina A, Katz D, et al. . Longitudinal shortening accounts for the majority of right ventricular contraction and improves after pulmonary vasodilator therapy in normal subjects and patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2011;140:27–33. 10.1378/chest.10-1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Kessel M, Seaton D, Chan J, et al. . Prognostic value of right ventricular free wall strain in pulmonary hypertension patients with pseudo-normalized tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion values. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;32:905–12. 10.1007/s10554-016-0862-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2017-000667supp001.docx (15.9KB, docx)