Abstract

Objectives

Massage therapy (MT) enhances recovery by reducing pain and fatigue in able-bodied endurance athletes. In athletes with disabilities, no studies have examined similar MT outcomes, yet participation in sport has increased by >1000 athletes from 1996 to 2016 Olympic games. We examined the effect of MT on pain, sleep, stress, function and performance goals on the bike, as well as quality of life off the bike, in elite paracycling athletes.

Methods

This is a quasi-experimental, convergent, parallel, mixed-methods design study of one team, with nine paracycling participants, in years 2015 and 2016. One-hour MT sessions were scheduled one time per week for 4 weeks, and then every other week for the duration of the time the athlete was on the team and/or in the study. Closed and open-ended survey questions investigating athlete goals, stress, sleep, pain and muscle tightness were gathered pre and post each MT session, and every 6 months for health-related quality of life. Quantitative analysis timepoints include baseline, 4–6 months of intervention and final visit. Additional qualitative data were derived from therapists’ treatment notes, exit surveys, and follow-up emails from the athletes and therapists.

Results

Significant improvement was found for sleep and muscle tightness; quantitative results were reinforced by athlete comments indicating MT assisted in their recovery while in training. There were no improvements in dimensions measuring quality of life; qualitative comments from athletes suggest reasons for lack of improvement.

Conclusion

This real-world study provides new information to support MT for recovery in elite paracyclists.

Keywords: massage therapy, disability, athletes, muscle tonus, sleep, quality of life

Key messages.

Massage therapy aids able-bodied athlete recovery. Until now, no studies have investigated the effects of massage therapy in a para-athlete population.

Massage therapy, however, showed no improvement in health-related quality of life for a small sample of elite paracyclists.

Our study showed that massage therapy assisted in para-athletes’ recovery, particularly in the area of reducing muscle tightness and in improving sleep.

Background

In the past 20 years, the number of disabled athletes competing at elite levels has increased, as is witnessed in the number of participants at the 1996 Summer Paralympics in Atlanta (n=3255) compared with the number of participants in 2016 in Rio (n=4328).1 The Paralympics is not the only venue for disabled athletes, as positive health and social benefits have been noted for those who participate in both professional and recreational adaptive sports.2–5 Yet studies demonstrate that para-athletes also have higher incidence and prevalence of injures compared with able-bodied athletes.6–9

The increasing number of disabled athletes, as well as increased risk of injuries, gives credence for investigation into ways to support disabled athletes during their training and sport competition. Massage therapy (MT) has been shown to improve recovery by reducing pain and fatigue in endurance able-bodied athletes.10 11 Additionally, a recent analysis of treatments pursued by athletes at the Pan American games indicates that MT was the most sought treatment, and more than half of MTs were performed by massage therapists.12 Reports suggest MT availability for para-athletes6 13 14; however, to our knowledge, outcomes of MT treatment have not been tracked for athletes with disabilities. While no identifiable evidence exists to support MT for disabled athletes, there is evidence for MT benefiting those with health conditions seen in para-athletes, such as spinal cord injury,15–17 cerebral palsy18 19 and amputation.20 21

Best and Crawford,22 as well as Poppendieck et al,23 suggest the need to investigate multiple bouts of massage during an athletic season for athletes to advance the science of massage and sport recovery.22–26 The purpose of this paper is to examine the effect of MT on pain, sleep, stress, function and performance goals on the bike, as well as the quality of life off the bike, in elite paracycling athletes in training from January 2015 until the Rio Olympics in 2016.

Methods

Participants

All members of Greenville Health System Team Roger C Peace (Greenville, South Carolina, USA), an elite paracycling team, were invited to join the study in 2015 and 2016. In 2015, a total of 9 of the team’s 11 athletes began the programme; two athletes left the team in 2015 and two athletes dropped from the study prior to completing the intervention. At the beginning of 2016, four new athletes joined the team and began the study protocol. While a total of 13 athletes completed the study visits; the data from only of nine athletes were used for this analysis after reviewing study visit timeline due to lack of consistent survey completion by the athletes and massage therapists. All participants signed a written informed consent.

Study design and intervention description

A quasi-experimental, convergent, parallel, mixed-methods design was used.27 Both qualitative and quantitative data were gathered in one phase of the research, analysed separately and then merged to find where the results converged. Merging the quantitative/qualitative data strengthened the overall outcome by providing more comprehensive results.27

In 2014, a standardised MT programme was designed with the intention to help a decentralised team of elite paracyclists to improve recovery, rest, performance and quality of life both on and off the bike. The decentralised nature of the paracycling team allowed for athletes to be on the same team and also to live across the country. Development of the programme is described elsewhere28 and included input from relevant stakeholders including athletes, coaches and massage therapists. In brief, the intervention allows for five different protocols (1, general relaxation; 2, muscle relaxation; 3, combination of general and muscle relaxation; 4, injury rehabilitation; and 5, integrated injury rehabilitation and general and/or muscular relaxation) to be integrated into clinical MT treatment based on an intake assessment survey, which also specified the athlete’s specific goals for the session.28 This type of flexible and adaptive protocol allows for individualised treatment of athletes based on their treatment goals and allows for the programme implementers (ie, massage therapists) to work within their strengths and skillsets.29–31 Massage therapists used to implement the programme were identified either by the athlete, through a search through a locator service, or through local and national contacts. For massage therapists to be qualified as implementers, they had to practise sports MT, be willing to be trained in and follow study protocols, and be willing to work with their assigned athlete. A total of 17 massage therapists were recruited and trained as implementers via online live webinar; more therapists were recruited than athletes, as some athletes worked with multiple massage therapists. Of the 17 massage therapists, 11 (64.71%) were female and all therapists had an average of 14 years (SD 8.59) in practice. Ten of the 17 therapists (58.8%) held a bachelor’s degree or higher; 58.8% had more than 600 hours of initial MT education. All massage therapists were paid their standard fees for their services and provided MT treatment in either their offices or in the athlete’s home.

On entering the study and signing informed consent, athletes were asked to schedule a 1-hour MT sessions one time per week for 4 weeks (eg, loading phase) and then every other week for the duration of the time (eg, maintenance phase) they were on the team and/or in the study. This schedule was chosen to try to minimise time burden on the athletes, as well as mirror ‘real-world’ clinical implementation. The maximum amount of MT sessions an athlete could obtain if they remained on the team and in the study over the 18-month period was 39 MT sessions.

Outcome measures

Quantitative data were gathered from the RAND Medical Outcomes Survey MOS Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36),32 33 or SF-36V34 (for non-ambulatory athletes), and on an MT session intake and exit questionnaires to measure stress, sleep, muscle tightness, spasticity and pain on a 10-point scale, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment.28 Qualitative data were obtained from open-ended questions on the massage intake and exit questionnaires, from the massage therapists’ treatment notes, from the programme exit questionnaire, as well as programme feedback emails provided by the athletes.

Data collection

On entering the programme, the athletes completed a health history form as well as either the SF-36 V.2 or SF-36V. The athletes subsequently filled out the SF-36 (or SF-36V) after the 14th MT session (approximately 6 months into the programme) and at the end of the programme. The MT session intake surveys were emailed to each athlete on the morning of their scheduled MT session; once the survey was completed, an email notification was sent to their massage therapist. Massage therapists also received an email link to their treatment notes on the morning of the scheduled session with their athlete. The morning after the MT session, athletes received the session exit survey to follow up on progress after treatment. All surveys were managed through the REDCap system, a secure and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant system for survey and database development.35

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis (SAS Enterprise Guide Software, V.7.1) included comparing the nine dimensions of SF-36 questionnaire and the 10-point scales for pain, sleep, function, spasticity and stress before, during and after the intervention. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyse the differences in comparison variables at three timepoints: baseline, at 4–6 months and at final visit. Further, multiple pairwise comparison was performed using Tukey’s test whenever a significant difference was revealed by repeated-measures ANOVA. The difference between intake and exit outcome variables was analysed at each timepoint separately using paired t-test. P values less than 0.1 are considered significant for this feasibility study.

Qualitative analysis (NVivo V.11 qualitative data analysis software; QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) began with data immersion by reading and rereading the text provided by the athletes and therapists. Next, word count queries were performed for each qualitative survey question, athlete feedback emails and the therapists’ notes to begin to understand potential patterns in the data.36 Then initial codes were created from the textual data through an iterative thematic analysis process of reading the data and highlighting text and assigning a code identifier.37 Once all the data were coded, emergent themes were identified by gathering similar codes together.37 The coding scheme evolved to have four major themes: goals for MT sessions, perceived benefits of MT sessions, beliefs and expectations about MT, and the interaction and importance of the therapeutic relationship with their massage therapist. These themes are mentioned here, in the Methods, as they then guided the integration of the quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative results tables were integrated with athlete and therapist comments from the representative themes. These qualitative quotations were used to explore and expand the understanding and of the quantitative findings.38 39

Results

Participants

Seven male and two female athletes of the Roger C Peace paracycling team (analysis n=9) with an average age of 39.14 (SD 9.23) years and an average time since injury/impairment of 19.09 years (SD 12.02) provided sufficient data for analysis. Figure 1 indicates the states where the athletes lived; it should be noted that one athlete split his time living in two separate states (Ohio and Florida) and received the intervention in both locations.

Figure 1.

State residence of athletes.

The athletes presented with varying impairments that limited activity: three with spinal cord injuries, two with amputations, one with stroke, one with traumatic brain injury, one with a lower limb crush injury leading to neuromuscular impairment, and one with cerebral palsy. In the sport of paracycling, an athlete’s level of impairment is evaluated and graded to allow athletes of similar abilities to compete against each other. Of the grades (1–5), a lower grade represents a greater physical impairment and limitation for activity; an athlete with a grade of 2 has a greater impairment and a higher level of disability than an athlete with a grade of 5.40 Additionally, there are four types of sport class categories in which athletes can compete: handcycle, tricycle, tandem and upright bicycle.40 The categories in which the athletes compete include three handcyclists (two H3, one H4), one tricycle (T1), and five cyclists (three C5, one C4, one C2).

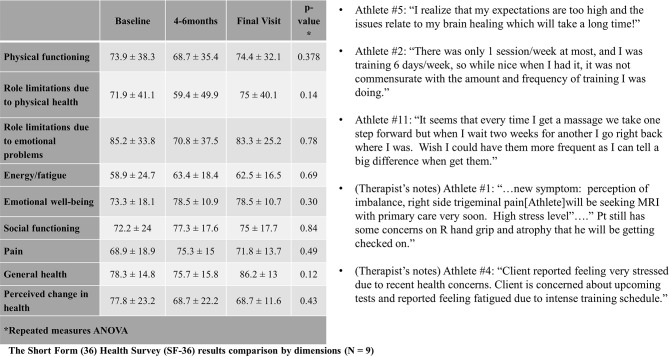

Athlete perceptions of quality of life

Athletes’ quality of life was quantitatively assessed with the SF-36 and confirmed with qualitative data (figure 2). The dimensions within the SF-36 are created by averaging items together, each scale totalling up to 100, with higher scores indicating higher quality of life. Athletes’ comments (figure 2) point to other indicators for lack of improvement, including the level of disability of the athletes, less than desired frequency of MT, amount of intense training and continued health issues for many of the athletes.

Figure 2.

Athletes’ perceptions of quality of life. Integration of quantitative and qualitative data. Results of SF-36 and quotes from athletes from quality of life and massage expectations themes. ANOVA, analysis of variance.

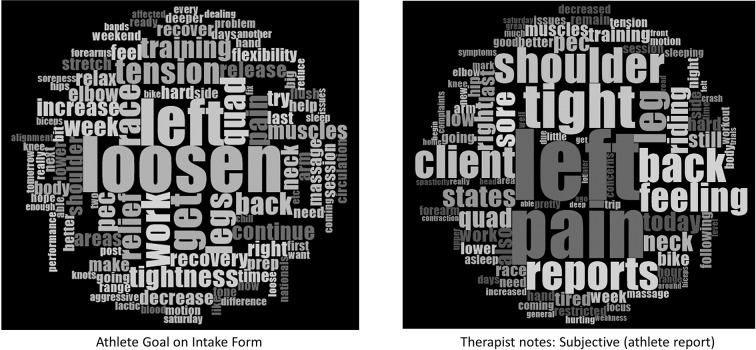

Athlete goals point to benefits and outcomes

The athletes indicated that reducing muscular tension was their most often sought goal for treatment, while pain reduction was mentioned less often on the session intake form (figure 3). However, within the therapist’s notes, pain reduction was mentioned as an athlete’s session goal (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Word frequencies displayed in a word cloud exploring the athlete’s goals for sessions from the athlete reported goal on the intake form and from the athlete report (verbal) to therapist as indicated by the therapist in their notes.

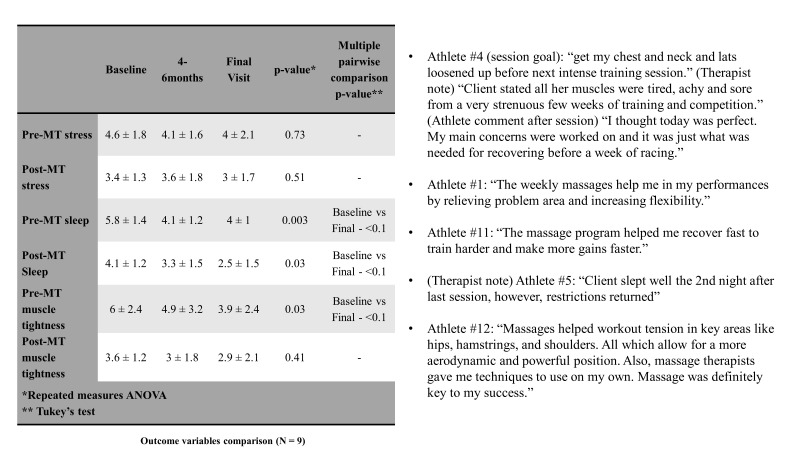

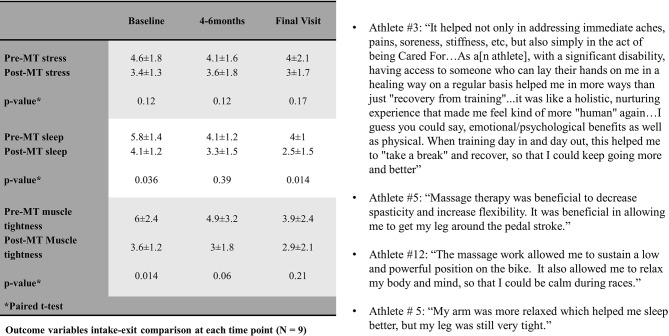

In figures 4 and 5, it should be noted that pain is not included in the outcome variable comparison, as the athletes did not sufficiently answer both intake and exit questions for this variable. Figure 4 looks at each variable longitudinally by pre-MT or post-MT. Figure 5 examines the variables pre-MT and post-MT to each other and longitudinally. The athletes report several benefits of treatment, with the most often reported benefit of assisting in recovery from training and racing including relief from symptoms and helping with sleep. These benefits from recovery led to improved training and racing performance.

Figure 4.

Athletes’ goals point to perceived benefits and outcomes. Integration of quantitative and qualitative data. Outcome variables comparison from intake (pre-MT) and exit forms (post-MT) and quotes from athletes and from therapist notes. ANOVA, analysis of variance; MT, massage therapy.

Figure 5.

Athletes’ perceived benefits and outcomes. Integration of quantitative and qualitative data. Comparison at each timepoint from intake exit (pre-MT and post-MT) forms and quotes from athletes and from therapist notes. MT, massage therapy.

Programme implementation

Programme implementation data and programme exit survey data indicated that the recommended protocol of one massage per week for 4 weeks and then every other week for the length of the study appeared to be difficult to follow. Athlete travel, life events, transportation issues and busy athlete schedules were indicated as barriers to maintaining the protocol. Additionally, while surveys were delivered electronically to both athletes and therapists, and therapists were expected to check the completion of the surveys prior to initiation of therapy session, survey completion for all sessions (intake, exit and therapist’s notes) was not consistently completed by all athletes or massage therapists.

Discussion

In this quasi-experimental, mixed-methods design study, elite paracycling athletes reported an improvement in muscular tension and sleep after MT treatment. This study found three noteworthy results: (1) Athletes’ expectations and programme implementation may have impacted the expected improvement in athletes’ quality of life. (2) Verbal intakes may be important when compared with written intake forms to help elucidate goals and improve treatment. (3) The athletes’ perceptions of the benefits of MT, mainly assisting in recovery, support the quantitative improvement in reduced muscle tightness and sleep.

MT improves the quality of life in many populations.41–45 Yet MT did not significantly improve quality of life as measured by the SF-36 instruments for the paracyclists. This could be because some of the expectations of treatment did not lead to the desired outcomes (as noted by the athletes’ comments from the qualitative data) or it could result from the inconsistent programme implementation.

The scarcity of reporting pain reduction as a goal of treatment in written form by the athletes versus the greater indication of pain reduction as a goal as indicated in the therapists’ notes may indicate the importance of communication between the therapist and the patient. Communication within an MT practice has not yet been investigated, but it has been mentioned as a critical component of care within the MT setting.46 47 Other healthcare literature indicates improved outcomes for patients with good healthcare provider communication48–51 and findings could be similar for MT treatment.

Additionally, while MT did not significantly improve pain or stress, another hypothesis could be an actual focus of the athletes to shift more from relieving pain to improving function, as is indicated by their most indicated goals of reducing muscle tightness/tension. This shift, from pain management to functional improvement, is mentioned as a new suggestion in the management of subacute and chronic pain in elite athletes by the International Olympic Committee (IOC); the IOC also suggests that treatment should take a multidisciplinary approach.52 In the IOC report, the committee does take special note of Paralympic athletes indicating they may have more pain than able-bodied athletes and therefore may have higher usage of pain medications, yet there is not mention of the multidisciplinary approach for these athletes.52 This lack of mention of additional approaches could be due to the current lack of evidence for MT benefiting Paralympic athletes.

Our study extends previous studies in various non-athlete and athlete populations (including those with breast cancer, pregnant women, older individuals, patients with fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, athletes and healthy individuals) indicating MT can aid in improving sleep44 53 54 and muscle tightness.45 55–57 Ours is the first study to investigate these outcomes in a para-athlete population. Integrating the qualitative results indicates that athletes felt that MT helped with recovery and training. The athletes clearly indicated in the qualitative data that they felt MT helped them to train harder, rest better and possibly perform better. These results mirror previous studies showing MT assisting in recovery from exercise in able-bodied individuals.11 58–60

Limitations and future directions

Results should be viewed with caution as the limitations include a small sample size with no comparison group. Furthermore, the measures used to evaluate change in the population are largely subjective, and the athletes and therapists did not consistently supply data via forms or consistently follow the recommended protocol. However, this study was implemented in real-world settings, and lack of consistent survey completion still led to positive outcomes.

Additionally, this is the first known study to follow decentralised athletes for this length of time, as most massage studies are short in duration (one to six sessions generally). This study shows continued improvements in muscle tightness and sleep over time. Further research is needed to explore the impact of MT on pain in this population, as well as investigate the effect of MT on para-athletes in other adaptive sports.

Conclusion

Previous work reported MT as a common technique for athletes to use to reduce recovery time,11 25 26 although to date no literature has explored the effects of MT in a para-athlete population. This real-world implemented study provides new information to support MT for recovery in elite paracyclists.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the massage therapists who implemented the study throughout the country. Their work and willingness to engage in the training and research process made this project possible. We would also like to thank the athletes of Team Roger C Peace, the team manager Jerry Page and the Director Sportif Jim Cunningham for their tireless efforts to train harder, recover quicker and find the best ways to support each other in the sport of paracycling as well as in life.

Footnotes

Contributors: ABK designed the intervention, analysed the qualitative data and prepared the manuscript. NP analysed the quantitative data and helped to prepare the manuscript. JLT helped to design the intervention and helped to prepare the manuscript.

Funding: This project was funded by the generous sponsorship of Team Roger C Peace by the American Massage Therapy Association.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Greenville Health System Office of Research Compliance and Administration (Pro00036860).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. International Paralympic Committee. Paralympic results & historical records. Int. Paralympic Comm. 2017. https://www.paralympic.org/results/historical (accessed 28 Aug 2017).

- 2. Lastuka A, Cottingham M. The effect of adaptive sports on employment among people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil 2015;7:1 10.3109/09638288.2015.1059497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blauwet C, Willick SE. The Paralympic Movement: using sports to promote health, disability rights, and social integration for athletes with disabilities. Pm R 2012;4:851–6. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jaarsma EA, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JH, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014;24:871–81. 10.1111/sms.12218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yazicioglu K, Yavuz F, Goktepe AS, et al. Influence of adapted sports on quality of life and life satisfaction in sport participants and non-sport participants with physical disabilities. Disabil Health J 2012;5:249–53. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gawronski W, Sobiecka J, Malesza J. Fit and healthy Paralympians--medical care guidelines for disabled athletes: a study of the injuries and illnesses incurred by the Polish Paralympic team in Beijing 2008 and London 2012. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:844–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fagher K, Lexell J. Sports-related injuries in athletes with disabilities. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014;24:e320–e331. 10.1111/sms.12175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Willick SE, Webborn N, Emery C, et al. The epidemiology of injuries at the London 2012 Paralympic Games. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:426–32. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Webborn N, Emery C. Descriptive epidemiology of paralympic sports injuries. Pm R 2014;6:S18–S22. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nunes GS, Bender PU, de Menezes FS, et al. Massage therapy decreases pain and perceived fatigue after long-distance Ironman triathlon: a randomised trial. J Physiother 2016;62:83–7. 10.1016/j.jphys.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Best TM, Hunter R, Wilcox A, et al. Effectiveness of sports massage for recovery of skeletal muscle from strenuous exercise. Clin J Sport Med 2008;18:446–60. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31818837a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siedlik JA, Bergeron C, Cooper M, et al. Advanced treatment monitoring for olympic-level athletes using unsupervised modeling techniques. J Athl Train 2016;51:74–81. 10.4085/1062-6050-51.2.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mendonça LD, Macedo CSG, Antonelo MC, et al. Preparation and organization of Brazilian physical therapy for the Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Phys Ther Sport 2017;25:62–4. 10.1016/j.ptsp.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gawroński W, Sobiecka J. Medical care before and during the winter paralympic games in Turin 2006, Vancouver 2010 and Sochi 2014. J Hum Kinet 2015;48 10.1515/hukin-2015-0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ayaş S, Leblebici B, Sözay S, et al. The effect of abdominal massage on bowel function in patients with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2006;85:951–5. 10.1097/01.phm.0000247649.00219.c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cardenas DD, Felix ER. Pain after spinal cord injury: a review of classification, treatment approaches, and treatment assessment. Pm R 2009;1:1077–90. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lovas J, Tran Y, Middleton J, et al. Managing pain and fatigue in people with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial feasibility study examining the efficacy of massage therapy. Spinal Cord 2017;55 10.1038/sc.2016.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Orhan C, Kaya Kara O, Kaya S, et al. The effects of connective tissue manipulation and Kinesio Taping on chronic constipation in children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40 10.1080/09638288.2016.1236412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whisler SL, Lang DM, Armstrong M, et al. Effects of myofascial release and other advanced myofascial therapies on children with cerebral palsy: six case reports. Explore 2012;8:199–205. 10.1016/j.explore.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shue S, Kania-Richmond A, Mulvihill T, et al. Treating individuals with amputations in therapeutic massage and bodywork practice: a qualitative study. Complement Ther Med 2017;32:98–104. 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown CA, Lido C. Reflexology treatment for patients with lower limb amputations and phantom limb pain–an exploratory pilot study. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2008;14:124–31. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Best TM, Crawford SK. Massage and postexercise recovery: the science is emerging. Br J Sports Med 2017;51 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Poppendieck W, Wegmann M, Ferrauti A, et al. Massage and performance recovery: a meta-analytical review. Sports Med 2016;46:183–204. 10.1007/s40279-015-0420-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zainuddin Z, Newton M, Sacco P, et al. Effects of massage on delayed-onset muscle soreness, swelling, and recovery of muscle function. J Athl Train 2005;40:174–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brummitt J. The role of massage in sports performance and rehabilitation: current evidence and future direction. N Am J Sports Phys Ther 2008;3:7–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moraska A. Sports massage. A comprehensive review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2005;45:370–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd edn Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kennedy AB, Trilk JL. A standardized, evidence-based massage therapy program for decentralized elite paracyclists: creating the model. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork 2015;8:3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haynes A, Brennan S, Redman S, et al. Figuring out fidelity: a worked example of the methods used to identify, critique and revise the essential elements of a contextualised intervention in health policy agencies. Implement Sci 2016;11:23 10.1186/s13012-016-0378-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Saunders RP. Implementation monitoring and process evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saunders RP, Evans AE, Kenison K, et al. Conceptualizing, implementing, and monitoring a structural health promotion intervention in an organizational setting. Health Promot Pract 2013;14 10.1177/1524839912454286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. : Stewart AL, Ware JE, Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham: Duke University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Luther SL, Kromrey J, Powell-Cope G, et al. A pilot study to modify the SF-36V physical functioning scale for use with veterans with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006;87:1059–66. 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. An array of qualitative data analysis tools: a call for data analysis triangulation. Sch Psychol Q 2007;22:557–84. 10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Legocki LJ, Meurer WJ, Frederiksen S, et al. Clinical trialist perspectives on the ethics of adaptive clinical trials: a mixed-methods analysis. BMC Med Ethics 2015;16:27 10.1186/s12910-015-0022-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res 2013;48:2134–56. 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aalgaard T. Get familiar with UCI paracycling classification terms: Canadian Cycling Magazines, 2015. https://cyclingmagazine.ca/sections/news/as-the-uci-paracycling-world-championships-roll-out-in-switzerland-get-familiar-with-classification-terms/ (accessed 6 Nov 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 41. Crawford C, Boyd C, Paat CF, et al. The impact of massage therapy on function in pain populations-a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: part i, patients experiencing pain in the general population. Pain Med 2016. [Epub ahead of print 10 May 2016]. 10.1093/pm/pnw099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hillier SL, Louw Q, Morris L, et al. Massage therapy for people with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD007502 10.1002/14651858.CD007502.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pan YQ, Yang KH, Wang YL, et al. Massage interventions and treatment-related side effects of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Oncol 2014;19:829–41. 10.1007/s10147-013-0635-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sturgeon M, Wetta-Hall R, Hart T, et al. Effects of therapeutic massage on the quality of life among patients with breast cancer during treatment. J Altern Complement Med 2009;15:373–80. 10.1089/acm.2008.0399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yuan SL, Matsutani LA, Marques AP. Effectiveness of different styles of massage therapy in fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Man Ther 2015;20 10.1016/j.math.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kennedy AB, Cambron JA, Sharpe PA, et al. Clarifying definitions for the massage therapy profession: the results of the best practices symposium†. Int J Ther Massage Bodyw Res Educ Pract 2016;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kennedy AB, Munk N. Experienced practitioners' beliefs utilized to create a successful massage therapist conceptual model: a qualitative investigation. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork 2017;10:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Di Blasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, et al. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 2001;357:757–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04169-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Maizes V, Rakel D, Niemiec C. Integrative medicine and patient-centered care. Explore 2009;5:277–89. 10.1016/j.explore.2009.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McAllister M, Matarasso B, Dixon B, et al. Conversation starters: re-examining and reconstructing first encounters within the therapeutic relationship. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2004;11:575–82. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00763.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tongue JR, Epps HR, Forese LL. Communication skills for patient-centered care: research-based, easily learned techniques for medical interviews that benefit orthopaedic surgeons and their patients. J Bone Jt Surg 2005;87-A:652–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hainline B, Derman W, Vernec A, et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on pain management in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1245–58. 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hollenbach D, Broker R, Herlehy S, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for sleep quality and insomnia during pregnancy: A systematic review. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2013;57:260–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McFeeters S, Pront L, Cuthbertson L, et al. Massage, a complementary therapy effectively promoting the health and well-being of older people in residential care settings: a review of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs 2016;11:266–83. 10.1111/opn.12115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Atkins DV, Eichler DA. The effects of self-massage on osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Int J Ther Massage Bodywork 2013;6:4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Eriksson Crommert M, Lacourpaille L, Heales LJ, et al. Massage induces an immediate, albeit short-term, reduction in muscle stiffness. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2015;25 10.1111/sms.12341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Weerapong P, Hume PA, Kolt GS. The mechanisms of massage and effects on performance, muscle recovery and injury prevention. Sports Med 2005;35:235–56. 10.2165/00007256-200535030-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ogai R, Yamane M, Matsumoto T, et al. Effects of petrissage massage on fatigue and exercise performance following intensive cycle pedalling. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:534–8. 10.1136/bjsm.2007.044396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Crane JD, Ogborn DI, Cupido C, et al. Massage therapy attenuates inflammatory signaling after exercise-induced muscle damage. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:119ra13 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kargarfard M, Lam ET, Shariat A, et al. Efficacy of massage on muscle soreness, perceived recovery, physiological restoration and physical performance in male bodybuilders. J Sports Sci 2016;34:959–65. 10.1080/02640414.2015.1081264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]