Abstract

Background

Even though the association between cigarette smoking and later substance use has been shown, there is still no compelling evidence that demonstrates the long-term effects in a high drug using community in African Americans. Few studies have examined the mediating mechanisms of the effect of adolescent cigarette smoking on the drug progression pathway.

Objectives

We examined the long-term influence of adolescent smoking on later illegal drug use in a cohort of urban African Americans, and the mediating role of educational attainment in the drug progression pathway.

Methods

The study used a longitudinal dataset from the Woodlawn Project that followed 1,242 African Americans from 1966–1967 (at age 6–7) through 2002–2003 (at age 42–43). We used the propensity score matching method to find a regular and a nonregular adolescent smoking group that had similar childhood characteristics; we used the matched sample to assess the association between adolescent smoking and drug progression, and the mediating role of educational attainment.

Results

Adolescent regular smokers showed significantly higher odds of using marijuana, cocaine, and heroin, having alcohol abuse problems and any drug dependence, and abuse problems in adulthood. We found that educational attainment mediated most of the drug progression pathway, including cigarette smoking, marijuana, cocaine and heroin use, and drug dependence or abuse problems in adulthood, but not alcohol abuse.

Conclusions

More focus needs to be put on high school dropout and development of interventions in community settings for African Americans to alter the pathway for drug progression for adolescents who use cigarettes regularly.

Keywords: African Americans, cigarette smoking, gateway theory, drug progression, substance use, propensity score matching

Introduction

In the United States, 23.9 million (9.2%) Americans 12 of age or older were current illegal drug users, and 22.2 million (8.5%) were classified with substance dependence or abuse in 2012 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013). Nationwide, the estimated cost of drug abuse—caused by morbidity, mortality, crime, and workforce losses—has increased an average of 5.3% per year from the early 1990s through 2002 (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2004). African Americans suffer from the highest drug-induced death rate compared to other races (Keppel, 2007), and are the second highest users of any illegal drug combined, second only to Native Americans, except for mixed races (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013).

Substance use and addictive behaviors are developed through various mechanisms, but besides genetic, structural, and environmental factors that are harder to change, public health researchers are interested in focusing more efforts on finding the signaling behaviors in early development, and in intervening in those factors and behaviors in early development that would lead to future substance use. One of the signaling behaviors that researchers and policy makers are interested in for intervention is early cigarette smoking (Castaldelli-Maia, Nicastri, Garcia de Oliveira, Guerra de Andrade, & Martins, 2014; Mathers, Toumbourou, Catalano, Williams, & Patton, 2006).

Several nationwide surveillance studies provide the numbers and patterns of adolescent smoking in the United States, such as the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS), which surveyed students in grades 9– 12 from 1991 to the present. According to the YRBS, cigarette smoking prevalence has been on a decline phase since the late 90s to the present. In YRBS, data showed that current cigarette use increased during 1991–1997 (27.5%–36.4%) and decreased during 1997–2013 (36.4%–15.7%) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Comparing racial differences in smoking prevalence for the past few decades, national datasets have found that African American adolescents have a lower cigarette smoking prevalence than White adolescents. Even though both African American and White 9th–12th graders increased smoking prevalence from 1991 to 1997 and decreased from 1997 to the present, African American adolescents have a much lower current smoking prevalence than White adolescents (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010a; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010b).

Although national data found that African American adolescents have a lower prevalence of current smoking, regional data show that urban African American adolescents have higher smoking prevalence than the overall national average across races (Delva et al., 2005; Eaton et al., 2008; Stillman et al., 2007). An alarming trend of smoking among African American adolescents and young adults was found in a sample collected in Baltimore inner-city neighborhoods: about 37% smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day and 15% smoked 1 pack per day (Stillman et al., 2007). The average starting age for smoking cigarettes for these inner-city African Americans was 13.6 (Stillman et al., 2007). Another study examined low-income African Americans in Detroit and found that 27% of youths 14–20 years of were current smokers (Delva et al., 2005). These numbers are higher than the prevalence of current smokers (20%) and those who smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day (10%) among 9–12th graders in a national survey (Eaton et al., 2008). The high prevalence of cigarette smoking among inner-city African American adolescents was observed not only in the current decade, but was also reported in the Woodlawn population—the sample used for this study. Among current smokers at age 15–16 in 1975–1976 (Juon, Ensminger, & Sydnor, 2002), 29% were adolescents. These statistics lend support to the importance of examining smoking patterns and associated behaviors among urban African Americans.

Cigarette smoking during adolescence has been found to be associated with future drug use, as suggested by the “gateway hypothesis,” which states that cigarette smoking as a gateway drug leads to the use of other substances (Kandel, 2002). The gateway hypothesis argues that drug use has various and sequential developmental stages, and that people who use drugs are at risk but do not inevitably progress into another type of drug. The stages of drug use development begins with legal drugs—cigarettes or alcohol—and then progress to illegal drug: first marijuana and then to other illegal drugs, such as cocaine and heroin (Kandel, 2002). Animal experimental models show that previous use of nicotine increased the likelihood of becoming addicted to cocaine after its first use, providing the molecular mechanism for the gateway hypothesis (Levine et al., 2011).

Based on the gateway hypothesis, many longitudinal studies have demonstrated the sequence of progression from legal to illegal drugs among adolescents and young adults, and in different ethnic groups and countries (Kandel, 2002). For cigarette smoking as the gateway drug, various studies have found a positive association of early cigarette smoking on later drug progression, such as future tobacco use (Ellickson, Tucker, & Klein, 2001), alcohol use (Chen et al., 2002; Juon et al., 2002), marijuana use (Ellickson et al., 2001; Juon et al., 2002), and other illegal drugs (Biederman et al., 2006; Brook, Brook, Zhang, Cohen, & Whiteman, 2002; Ellickson et al., 2001; Juon et al., 2002). In the review by Mathers et al. (2006)—based on longitudinal studies from 1980 to 2005 that looked at the association between tobacco use under 18 years of age and outcomes at 18 years of age or older—early tobacco smoking was a risk marker for later alcohol initiation and alcohol-related problems, such as alcohol abuse, dependence, and binge drinking (Brook et al., 2002; Ellickson et al., 2001; Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Brown, 1999). A retrospective study that used a non-U.S. sample evaluated the transitions of drug use involving inhalants, and also found a transition from tobacco to inhalants (Castaldelli-Maia et al., 2014). In longitudinal studies that examined the association between adolescent smoking and substance abuse, age at follow-up ranged from 18 to 32 years; the majority of follow-up times were under age 30 (Mathers et al., 2006). Our study provides an advantage by extending the follow-up age to 42–43 to examine drug progression in adulthood based on a prospective longitudinal study design.

Our study also provides a unique opportunity to examine the gateway hypothesis in a high-drug-using African American community. In our study population of the Woodlawn cohort, lifetime prevalence for substance was as follows: 97% for alcohol, 75.7% for tobacco, 58.3% for marijuana, 29.9% for cocaine or crack, and 7.6% for heroin in mid-adulthood (Doherty, Green, Reisinger, & Ensminger, 2008). Based on data of the National Household Survey of Drug Abuse, the Woodlawn cohort has higher rates of lifetime and prior year illegal drug use in young adulthood than the nation and the national African American counterparts, but reached rates of illegal drug use similar to other African Americans when they aged to mid-adulthood (age 42) (Doherty et al., 2008).

Only a few studies that have focused on the long-term association between early cigarette smoking and later drug use have also examined this subject among ethnic groups or examined those who are high drug-using and who have lower socioeconomic status. Golub and Johnson (2002) found that the general population followed the gateway hypothesis, progressing from alcohol or tobacco to marijuana and hard drug use, while a substantial proportion of inner-city residents and a hard drug-using population used marijuana before alcohol or tobacco, and some hard drug users did not have prior marijuana use. In a large cross-national sample based on users age cohort and country differences, Degenhardt et al. (2010) examined whether the risk of later drug use in the sequence changed in use prevalence, when conditioned on the use of drugs earlier in the sequence. They showed that violations of the steps of the gateway theory seem to be related to the local culture of consumption. Thus, the model of transition in the gateway hypothesis may vary between ethnic groups. In the United States, African-American youth were significantly more likely to begin marijuana use before cigarette use than their Caucasian peers in a sample of juvenile offenders (Vaughn, Wallace, Perron, Copeland, & Howard, 2008). These variations and different strengths of association by ethnicity highlight the need to examine the gateway theory within ethnic groups and populations at higher risk for illegal drug use.

To consider one of the major gaps of the gateway hypothesis—mediator variables explaining the transition from use of one drug to the use of other drugs—we examined the mediating role of educational attainment in adulthood. In the United States, college graduates have the lowest rate of being current illegal drug users (6.6%), followed by high school graduates (9.8%), and by some college education (10.2%). Those who did not graduate from high school have the highest rate of being drug users in year 2012 (11.1%) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013).

The hypothesized mediating role of educational attainment in the pathway from adolescent cigarette smoking to substance use in middle adulthood is supported by two theories related to adolescent risky behaviors: the Social Control Theory and the Problem Behavior Theory (Hirschi, 1969; Jessor & Jessor, 1977). Hirschi’s Social Control Theory suggests that the variation of strengths of social bond is associated with deviance; specifically, people with a lower level of social bond may be more likely to engage in deviance (Hirschi, 1969). School serves as an important social context for adolescents; the attachment to the school context, indicated by dropping out of high school, may affect later likelihood of engaging in deviance. The Problem Behavior Theory suggests that adolescents involved with any one problem behavior have a higher risk of being involved in other problem behaviors due to the influence of social peers and the shared meanings and function of these problem behaviors (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). High school dropout—lower educational attainment—might be a mediator in the pathway from adolescent smoking to later illegal drug use.

Although there is no direct evidence demonstrating the mediating role of educational attainment in the drug progression pathway, robust findings in the literature demonstrate the association between cigarette smoking and educational attainment, and the association between educational attainment and substance use outcomes to support the mediating hypothesis. The independent association between cigarette smoking and education is well documented in the literature (Barbeau, Krieger, & Soobader, 2004; Gilman, Abrams, & Buka, 2003; Jefferis, Graham, Manor, & Power, 2003; Lowry, Kann, Collins, & Kolbe, 1996; Yang, Lynch, Schulenberg, Roux, & Raghunathan, 2008). After adjusting for race/ethnicity, age, and gender in the U.S. population with NHIS data, individuals without a college degree and individuals who are blue-collar workers have more than two-fold odds of being current smokers than those with college degrees and being white-collar workers (Barbeau et al., 2004). Data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health indicate that, after adjusting for age and race, men who had no further education and were economically inactive had four times greater odds of heavy smoking than men with further education (Yang et al., 2008). We also previously demonstrated the association of adolescent smoking on later educational attainment with the same study sample as this paper using a propensity score matching method (Strong, Juon, & Ensminger, 2014). On the other hand, educational attainment was found to be associated with the use of alcohol (Melotti et al., 2011), marijuana (Grant et al., 2012), and other drugs (Fothergill et al., 2008). Lower educational attainment, such as underachievement in first grade and not having a high school diploma, was associated with adult problem drug use using the Wood-lawn sample (Fothergill et al., 2008).

To further advance the gateway hypothesis, we hypothesized that educational attainment may mediate the association of cigarette smoking in adolescence and substance use in middle adulthood. This paper addresses the following specific questions: (1) Given similar childhood and familial characteristics, do individuals who smoke cigarettes regularly during adolescence have an increased risk of substance use and abuse problems in adulthood? (2) Does educational attainment mediate the impact of regular cigarette smoking in adolescence to drug progression in adulthood?

Method

Propensity score matching

The association between adolescent smoking and adult drug progression may be due to selection bias. An individuals’ background factors associated with his/her adolescent cigarette use could also be the cause of substance use in adulthood. Our study examines whether cigarette smoking itself still has a strong association with illegal drug use in this high drug-using community, taking into account individual factors and family background. To adjust for this selection bias and to distinguish the association of cigarette smoking, the propensity score matching method was used to select a group of regular adolescent smokers and a group of nonregular adolescent smokers that have similar distributions of observed covariates (Reiter, 2000; Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983). Traditional regression analysis yields bias estimates when the two comparison groups have very different multivariate distribution, while propensity score matching relies less on extrapolation and model-based assumptions (E. A. Stuart & Rubin, 2007); hence, we used the propensity score matching method, instead of traditional regression analysis.

The propensity score matching method has been getting more attention in the field of medical literature and social epidemiology (Austin, 2008). Applications of propensity score matching in examining longitudinal effects in observational research include, but are not limited to, studies that looked at developmental trajectory (Haviland, Nagin, Rosenbaum, & Tremblay, 2008) and substance use (Doherty, Green, & Ensminger, 2008; Green & Ensminger, 2006; S. Guo, Barth, & Gibbons, 2006; Harder, Stuart, & Anthony, 2008; Magura, McKean, Kosten, & Tonigan, 2013; E. A. Stuart & Green, 2008; Timberlake, Huh, & Lakon, 2009; Wolf & Wolf, 2008). In the cigarette smoking literature, the key article that used propensity score matching traced back to Rubin’s 2001 article on tobacco litigation. The author demonstrated various propensity score matching methods to select smokers and nonsmokers that have the same multivariate distribution of covariates and compared the bias reduction by various matching methods (Rubin, 2001). Another study used propensity score matching to evaluate the gateway hypothesis of smokeless tobacco on smoking. The authors found that after matching on propensity score, there was no association between smokeless tobacco and becoming a smoker, while significant association was found in the unadjusted analysis prior to matching (Timberlake et al., 2009). They concluded that the significant differences between smokeless tobacco users and non-users found before adjustment or matching may be due to their baseline differences in the risk factors; hence, it showed the importance of using propensity score matching to control for the differences in baseline characteristics (Timberlake et al., 2009).

Study participants

The Woodlawn Project is a prospective, longitudinal study that started in 1966–1967 (T1) and consists of a cohort of first graders (ages 6–7, n = 1242) from Woodlawn on the south side of Chicago. All first graders in the nine public and three parochial schools and their families were asked to participate. This cohort of first graders was then followed during adolescence (ages 15–16) in year 1975–1976 (T2), young-adulthood (ages 32–33) in year 1992–1993 (T3), and mid-adulthood (ages 42–43) in year 2002–2003 (T4). The retention percentage was lower at T2 due to funding shortage, and only those who remained in the Chicago area and whose mothers were interviewed at this phase were contacted during adolescence (n = 705). In T3 and T4, 952 individuals completed the interview at T3, and 833 completed the T4 interview (Green, Doherty, Stuart, & Ensminger, 2010). Woodlawn was the fifth poorest of the 76 Chicago communities in the mid 1960s when the study first started. At that time, it was composed of 99% African Americans and 51.2% females (Kellam, Branch, Agrawal, & Ensminger, 1975). More detail on attrition analyses can be found in our previous publication (Strong et al., 2014).

Measures

Dependent variables

Assessments of marijuana, heroin, and cocaine use were developed based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Anthony, Warner, & Kessler, 1994; Fothergill & Ensminger, 2006). Drug abuse and dependence were generated based on DSM-III-R criteria in T3 and DSM-IV in T4, using the CIDI module. Cigarette smoking at T3 was categorized into not smoking now (never smoked or past smokers) versus current users (smoking less than half a pack per day, and smoking more than half a pack per day). Cigarette smoking at T4 was defined as not smoking now versus smoking now. Marijuana use at T3 was defined as never or used previously (used but not in the past year) versus using now (used in the past year). Marijuana at T4 was categorized as did not use and used between T3 and T4. Recent cocaine and heroin use at T3 were both dichotomized into yes and no. Recent cocaine and heroin use at T4 were defined as whether they were used between T3 and T4. Participants were categorized as having alcohol abuse or dependence in either T3 or T4, or not at all in adulthood. For drug abuse and dependence problems, answers were dichotomized as having dependence or abuse of any illegal drug excluding alcohol in either T3 or T4, or not any.

Mediator (T3)

Self-reported educational attainment was assessed in both young adulthood (T3) and mid-adulthood (T4). Participants were asked, “What is the highest grade in elementary or high school that you finished and got credit for?” Using data from both waves, educational attainment was categorized into low (no diploma or with a GED) and high (high school graduate or higher).

Independent variable (T2)

Adolescents were asked to self-report their frequency of current smoking status on a scale of never, only 1–2 times ever, occasionally, less than one pack a day, or a pack a day or more. A dichotomous variable was created. Adolescents who marked on the scale that they never smoked, only smoked 1–2 times ever, or occasionally smoked were categorized as non-regular smokers. Adolescents who marked on the scale that they smoked less than a pack a day or a full pack or more per day were categorized as regular smokers.

Matching variables

Gender

Mother’s smoking and alcohol use status

Mother’s smoking and alcohol use status were self-reported by mothers or mother surrogates at the time of the adolescent interview asking how much they had used cigarettes or alcohol in the last 12 months. Answers of smoking and alcohol use were categorized separately into regular or nonregular users.

Family socioeconomic status (SES)

The mothers’ SES was indicated by their educational attainment at T1, the amount of schooling they had completed. Answers were dichotomized: high (finished high school or more) and low (did not finish high school or lower). Poverty level and whether the family received welfare at T1 were also used to indicate family socioeconomic status.

Childhood behavioral characteristics

Teachers were asked to rate each child on five aspects of school adaptation—immaturity, shyness, aggressiveness, underachievement, and restlessness—on a scale of 0 (adapting) to 3 (severely maladapting) using the Teacher’s Observation of Classroom Adaptation (TOCA) scale at T1 (Kellam et al., 1975).

School performance

Teachers were asked to report each child’s reading grades at T1 on a scale of 1 (excellent) to 4 (unsatisfactory).

Expectation for educational attainment

Mothers were asked at T1 about how far they thought their child would actually go in school on a scale of 1 (some high school or finish high school) to 4 (beyond college).

Residential mobility

Mothers were asked how many times they had moved after the child was born, up to the time interviewed in T1 (answers ranged from 0 to 9).

Mother’s mental health

Mothers’ early psychological distress at T1 was measured separately by the frequency of their self-reported anxious or depressed moods on a scale of 1 (hardly ever) to 4 (very often).

Children’s psychological symptoms

Using 33 items from the Mother’s Symptom Inventory, adapted from Connors’ instrument (Conners, 1967; Conners, 1967; Juon, Ensminger, & Feehan, 2003), mothers were asked to rate how true were the following statements as to whether the child had each problem on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much) at T1: symptoms such as restless or awakens at night, afraid of new situations, looks sad, stutters, etc. (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83). After summing up the total scores of the 33 items, the scores were categorized into three groups: low (0–6), medium (7–12), high (13 or more points).

Analysis

Propensity score matching

We used the propensity score matching method to account for early-life or childhood covariates in relation to adolescent smoking, and to obtain a matched sample, following the methods used in our previous study on the same sample of this study (Strong et al., 2014). Propensity score matching was conducted with psmatch2 in Stata statistical software (StataCorp, 2007). The propensity score was first estimated with logit function by matching variables listed in the Matching Variables section above. By creating propensity scores for all study participants using the covariates (the Matching variables), we reduced multiple characteristics to a one-dimensional score (Guo & Fraser, 2010). We balanced the data by this method to render the confounding effect of covariates. Good balance was determined by having improved balance, with standardized bias lower than 0.25 after matching (Ho, Imai, King, & Stuart, 2007), and by having similar covariate distributions in the matched treatment and control groups. Once the matching was completed, a matched sample was selected and used for outcome analysis.

Outcome and mediation analysis

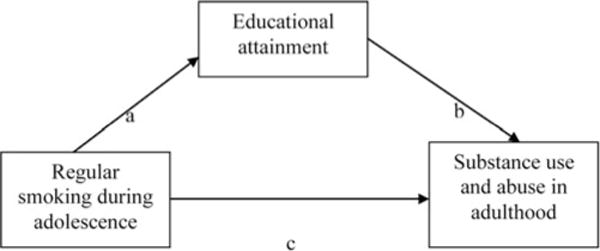

We used the matched sample to estimate the association between adolescent regular smoking and substance use and abuse in mid-adulthood. To examine the mediation role of educational attainment in the pathway of adolescent regular smoking on substance use and abuse in adulthood, we used the product of two coefficients: path a and path b (Figure 1). The product of these two coefficients indicates the mediation effect (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007). First, we used Stata to obtain the standardized coefficients and SEs for path a and b, and then entered into the RMediation package to obtain the 95% confidence interval for the product of these two coefficients of path a and b in R statistical software (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). If the confidence interval did not include 0, then the mediation was significant. This method has been used in the literature for categorical variables (Perkins & Forehand, 2012; van Nimwegen et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

Mediation model. The relation between the independent variable—regular smoking during adolescence—on the dependent variables substance use and abuse is mediated through educational attainment. “a” represents the association between adolescent regular smoking, “b” represents the strength of the association between educational attainment and substance use and abuse in adulthood, and “c” represents the association between regular smoking during adolescence and substance use and abuse in adulthood.

Missing data

All the missing values in each covariate used for matching were less than 7%. We used mean and mode replacement for matching variables that had less than 5% missing values for continuous and categorical variables. For matching variables that had missing values more than 5%, we generated a “missing” category. Out of 703 study participants, 15% did not complete the T3 survey and 27% did not complete the T4 survey. For outcome variables, we imputed 5 datasets using variables in four phases in the dataset with the ICE program in Stata (Royston, 2004) and used the multiply imputed dataset for outcome analysis with the MIM program in Stata (Carlin, Galati, & Royston, 2008).

Results

Cigarette smoking, alcohol, and illegal drug use before matching

Among 703 adolescents, 29% were regular smokers and 71% were nonregular smokers. Only 14% of regular-smoking adolescents reported having quit smoking in T3. These regular adolescent smokers continued to have higher prevalence of cigarette smoking in adulthood. About 64% of regular-smoking adolescents continued smoking in T3, and 50% continued smoking in T4.

Overall, these 703 participants had high substance use behavior in adulthood (Table 1). Among the adolescent cigarette smokers, about 33% smoked more than a pack per day and 42% smoked less than a pack per day in T3, and 73% still smoked in T4. Among the adolescent non-regular smokers, about 16% smoked more than a pack a day; 23% smoked less than a pack a day in T3 and 32% still smoked cigarette in T4. About 35% of adolescent regular smokers had alcohol abuse problems at T3 or T4, compared to 19% for adolescent non-regular smokers. About 29% of adolescent regular smokers used marijuana at T3 and 40% at T4, compared to 16% at T3 and 23% at T4 for adolescent nonregular smokers. For adolescent regular smokers, at T3 cocaine use was 36% and heroin use was 13%; at T4 heroin use was 27% and cocaine use was 9%. For adolescent non-regular smokers, at T3 cocaine use was 21% and heroin use was 3%, and at T4 cocaine use was 14% and heroin use was 4%.

Table 1.

Descriptive and bivariate analysis for adult substance use outcomes before matching (N = 703).

| Substance use in adulthood | Complete (N = 703) | Regular adolescent smokers (N = 206, 29%) | Nonregular adolescent smokers (N = 497,71%) | χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette | ||||||

| Current cigarette use in T3 | Yes | 298 (49.92%) | 131 (75.29%) | 167 (39.48%0 | 63.23 | <0.001 |

| No | 299 (50.08%) | 43 (24.71%) | 256 (60.52%) | |||

| Current cigarette use in T4 | Yes | 222 (43.61%) | 104 (72.73%) | 118 (32.24%) | 68.54 | <0.001 |

| No | 287 (56.39%) | 39 (27.27%) | 248 (67.76%) | |||

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence in T3 or T4 | Yes | 151 (23.82%) | 65 (35.33%) | 86 (19.11%) | 18.92 | < 0.001 |

| No | 483 (76.18%) | 119 (64.67%) | 364 (80.89%) | |||

| Marijuana | ||||||

| Current marijuana use in T3 | Yes | 119 (19.93%) | 51 (29.31%) | 68 (16.08%) | ||

| No | 478 (80.07%) | 123 (70.69%) | 355 (83.92%) | 13.53 | < 0.001 | |

| Recent marijuana use in T4 | Yes | 142 (28.12%) | 57 (40.43%) | 85 (23.35%) | 14.66 | < 0.001 |

| No | 363 (71.88%) | 84 (59.57%) | 279 (76.65%) | |||

| Cocaine | ||||||

| Recent cocaine use in T3 | Yes | 151 (25.29%) | 62 (35.63%) | 89 (21.04%) | 13.89 | < 0.001 |

| (Used in past year & before) | No | 446 (74.71%) | 112 (64.37%) | 334 (78.96%) | ||

| Recent cocaine use in T4 | Yes | 88 (17.39%) | 38 (26.95%) | 50 (13.70%) | 12.43 | < 0.001 |

| (Used between T3 & T4) | No | 418 (82.61%) | 103 (73.05%) | 315 (86.30%) | ||

| Heroin | ||||||

| Recent heroin use in T3 | Yes | 36 (6.03%) | 22 (12.64%) | 14 (3.31%) | 18.96 | < 0.001 |

| (Used in past year & before) | No | 561 (93.97%) | 152 (87.36%) | 409 (96.69%) | ||

| Recent heroin use in T4 | Yes | 28 (5.51%) | 13 (9.15%) | 15 (4.10%) | 5.02 | 0.03 |

| (Used between T3 & T4) | No | 480 (94.49%) | 129 (90.85%) | 351 (95.90%) | ||

| Drug dependence or abuse | ||||||

| T3 or T4 drug abuse or dependence | Yes | 116 (18.33%) | 57 (30.81%) | 59 (13.17%) | 27.22 | < 0.001 |

| No | 517 (81.67%) | 128 (69.19%) | 389 (86.83%) |

About 31% of adolescent smokers were dependent on or abused any illegal drug in adulthood, compared to 13% for adolescent non-regular smokers.

Without any adjustment for confounders and before matching, regular smoking in adolescence was associated with most of the substance use outcomes in mid-adulthood (see Table 1), including cigarettes and alcohol. For illegal drug use and dependence, a higher percentage of adolescent regular smokers also used marijuana, cocaine, or heroin, and were dependent or abused any illegal drug in young- and mid-adulthood.

Propensity score matching

Before propensity score matching, bivariate analysis for matching variables in childhood indicated that adolescents who were regular smokers were more likely to be male, have a higher score for teacher assessments of aggressive and restless behavior, have a mother who regularly smoked, and have higher residential mobility in childhood (see Table 2). A matched sample was selected, using 1–1 nearest neighbor matching without replacement within a caliper of width of a quarter of the standard deviation of propensity score. The matched sample was composed of 199 regular smokers and 199 non-regular smokers in adolescence. All the absolute standardized bias of the matching variables was below 25% after matching, and none of the matching variables was significantly associated with regular smoking in adolescence (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of matching covariates for regular and nonregular adolescent smokers before matching and standardized bias before and after matching (N = 703).

| Matching variables | Regular smoking (N = 206) | Nonregular smoking (N = 497) | p-value | Standardized bias before matching | Standardized bias after matching |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.03 | 0.19 | −0.15 | ||

| Female | 92 (45%) | 268 (54%) | |||

| Male | 114 (55%) | 229 (46%) | |||

| Mother’s education | 0.32 | ||||

| < high school** | 119 (58%) | 272 (55%) | |||

| High school or higher | 72 (35%) | 199 (40%) | −0.11 | 0.12 | |

| Missing | 15(7%) | 26 (5%) | 0.09 | − 0.12 | |

| Poverty index at T1 | 0.18 | 0.15 | − 0.12 | ||

| Poverty | 113 (55%) | 235 (48%) | |||

| No | 83 (40%) | 237 (48%) | |||

| Missing§ | 10 (5%) | 25 (5%) | |||

| Welfare index at T1 | 0.22 | 0.07 | − 0.15 | ||

| On welfare | 71 (34%) | 155 (31%) | |||

| No | 130 (63%) | 337 (68%) | |||

| Missing§ | 5 (2%) | 5 (1%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Child’s behavior | |||||

| Immaturity [0–3] | 0.65 (0.98) | 0.57 (0.93) | 0.36 | 0.08 | − 0.11 |

| Shy [0–3] | 0.47 (0.84) | 0.45 (0.80) | 0.76 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Aggressiveness [0–3] | 0.7 (1.01) | 0.44 (0.85) | <0.01 | 0.28 | − 0.24 |

| Underachievement [0–3] | 0.68 (0.94) | 0.63 (0.95) | 0.49 | 0.06 | − 0.08 |

| Restlessness [0–3] | 0.73 (1.04) | 0.50 (0.93) | < 0.01 | 0.24 | − 0.18 |

| Missing*§ | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | |||

| Child’s personality symptoms | 0.69 | ||||

| Low** | 82 (40%) | 175 (35%) | |||

| Medium | 67 (33%) | 175 (35%) | − 0.06 | 0.02 | |

| High | 56 (27%) | 143 (29%) | − 0.04 | 0.16 | |

| Missing§ | 1 (.5%) | 4 (1%) | |||

| Reading ability | 0.10 | ||||

| Low (fair/unsatisfactory)** | 78 (38%) | 232 (47%) | |||

| High (good/excellent) | 114 (55%) | 233 (47%) | 0.17 | − 0.09 | |

| Missing | 14 (7%) | 32 (6%) | 0.01 | − 0.01 | |

| Mother’s smoking status | < 0.01 | 0.26 | − 0.13 | ||

| Yes | 99 (48%) | 176 (35%) | |||

| No | 102 (50%) | 300 (60%) | |||

| Missing§ | 5 (2%) | 21 (4%) | |||

| Mother uses alcohol regularly | 0.14 | 0.16 | − 0.07 | ||

| Yes | 27 (13%) | 41 (8%) | |||

| No | 173 (84%) | 441 (89%) | |||

| Missing§ | 6 (3%) | 15 (3%) | |||

| Mother’s anxiety (nervous/tense/edgy) | 0.23 | ||||

| Hardly ever** | 25 (12%) | 78 (16%) | |||

| Occasionally | 94 (46%) | 233 (47%) | − 0.03 | 0.13 | |

| Fairly often | 25 (12%) | 74 (15%) | − 0.08 | 0.13 | |

| Very often | 47 (23%) | 88 (18%) | 0.13 | − 0.2 | |

| Missing | 15 (7%) | 24 (5%) | 0.1 | − 0.12 | |

| Mother’s depression (sad/blue) | 0.22 | ||||

| Hardly ever** | 72 (35%) | 196 (39%) | |||

| Occasionally | 94 (46%) | 195 (39%) | 0.13 | − 0.02 | |

| Fairly often | 12 (6%) | 43 (9%) | − 0.11 | 0.04 | |

| Very often | 13 (6%) | 39 (8%) | − 0.06 | 0.13 | |

| Missing | 15 (7%) | 24 (5%) | 0.1 | − 0.12 | |

| Mother’s expectation of education achievement | 0.91 | ||||

| Up to finishing high school** | 31 (15%) | 63 (13%) | |||

| Some college | 15 (7%) | 42 (8%) | − 0.04 | 0.01 | |

| Finish college | 126 (61%) | 313 (63%) | − 0.03 | 0.05 | |

| Beyond college | 32 (16%) | 75 (15%) | 0.01 | 0 | |

| Missing§ | 2 (1%) | 4 (1%) | |||

| Residential mobility (times moved) | |||||

| Mean (SD) [0–9] | 2.38 (1.80) | 2.09 (1.68) | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.02 |

| Missing§ | 0 (0%) | 2 (.4%) |

applied to all items in “child’s behavior”

For missing values that are less than 5%, simple mean/mode replacement was used for missing values; hence, no missing category was used for matching and no standardized bias was calculated.

First category was used as reference when matching as categorical variable, hence no standardized bias was calculated.

Outcome analysis

The results of regression analysis for the association between adolescent regular smoking and substance use outcomes in mid-adulthood with the matched sample are shown in Table 3. Adolescent regular smokers have about 5 times the odds of smoking a high quantity of cigarettes in adulthood, compared to those who did not smoke regularly in adolescence (T3-OR: 5.79, 95% CI:3.23–10.38; T4-OR:4.94, 95%CI: 2.08–11.71). Adolescent regular smokers also show significantly higher odds of having alcohol abuse problems (T3/4-OR: 1.99, 95% CI: 1.26–3.13), using marijuana (T4-OR: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.02–2.75), cocaine (T3-OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.01–2.54; T4-OR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.09–2.43), and having any drug dependence and abuse problems in adulthood (T3/4-OR:3.44, 95% CI: 2.01–5.88).

Table 3.

Association between adolescent regular smoking and adulthood substance use and abuse outcomes, using propensity score matched sample of 398 individuals from the Woodlawn study, 1966–2002 (N = 199 for regular smokers in T2 vs. N = 199 for nonregular smokers in T2).

| Substance use in T3 and T4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Using the matched sample | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

| Cigarette | |||

| Current cigarette use in T3 | 4.64 | 3.00–7.17 | <0.001 |

| Current cigarette use in T4 | 4.02 | 2.77–5.84 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol | |||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence in T3 or T4 | 1.99 | 1.26–3.13 | < 0.001 |

| Marijuana | |||

| Current marijuana use in T3 | 2.07 | 1.34–3.19 | 0.001 |

| Recent marijuana use in T4 | 1.68 | 1.02–2.75 | 0.04 |

| Cocaine | |||

| Recent cocaine use in T3 | 1.6 | 1.01–2.54 | 0.05 |

| Recent cocaine use in T4 | 1.62 | 1.09–2.43 | 0.02 |

| Heroin | |||

| Recent heroin use in T3 | 2.06 | 1.00–4.23 | 0.05 |

| Recent heroin use in T4 | 1.24 | 0.76–2.02 | 0.39 |

| Drug dependence or abuse | |||

| T3 or T4 drug abuse or dependence | 3.44 | 2.01–5.88 | < 0.001 |

Mediation analysis

Of the 703 adolescents, 24% had not finished high school in T3. Adolescent regular smokers were significantly more likely to report lower educational attainment (OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.34–3.39) in T3. The mediation effect (product of standardized coefficient in path a and path b in Figure 1), the standard error and estimated 95% confidence interval, are shown in Table 4. Based on whether the confidence interval covers 0, we found that educational attainment mediated most of the association between adolescent smoking and later drug use, such as cigarette smoking, marijuana, cocaine, or heroin use and drug dependence or abuse, but did not significantly mediate the association between adolescent smoking and alcohol abuse in adulthood.

Table 4.

Mediation analysis of educational attainment in the pathway of adolescent regular cigarette smoking and adulthood drug progression, using the propensity score matched sample of 398 individuals from the Woodlawn study, 1966–2002 (N = 199 for regular smokers in T2 vs. N = 199 for nonregular smokers in T2).

| Mediation effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Substance use in T3 and T4 | ab* | SE | 95% confidence interval |

| Cigarette | |||

| Current cigarette use in T3 | 0.716 | 0.334 | 0.169 to 1.465 |

| Current cigarette use in T4 | 0.616 | 0.291 | 0.142 to 1.268 |

| Alcohol | |||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence in T3 or T4 | 0.328 | 0.229 | −0.052 to 0.843 |

| Marijuana | |||

| Current marijuana use in T3 | 0.609 | 0.286 | 0.143 to 1.250 |

| Recent marijuana use in T4 | 0.617 | 0.274 | 0.165 to 1.228 |

| Cocaine | |||

| Recent cocaine use in T3 | 0.531 | 0.295 | 0.055 to 1.197 |

| Recent cocaine use in T4 | 0.759 | 0.245 | 0.245 to 1.423 |

| Heroin | |||

| Recent heroin use in T3 | 0.676 | 0.348 | 0.112 to 1.461 |

| Recent heroin use in T4 | 0.622 | 0.300 | 0.134 to 1.295 |

| Drug dependence or abuse | |||

| T3 or T4 drug abuse or dependence | 0.540 | 0.284 | 0.080 to 1.180 |

Product of the standardized coefficients of the a and b paths, in which a is the standardized coefficient of the association between regular smoking during adolescence and educational attainment in young adulthood, and b is the standardized coefficient of the association between educational attainment and substance use and abuse in adulthood.

Discussion

Using the propensity score matching method, our study provides evidence for the association between adolescent cigarette smoking and substance use, abuse, and dependence problems in mid-adulthood. It also provides evidence for the mediating role of educational attainment on the pathway of early cigarette smoking to adulthood cigarette smoking, marijuana, cocaine and heroin use, and drug abuse or dependence problems, but does not provide evidence to mediate the pathway to alcohol abuse.

Consistent with most of the literature, early cigarette smoking has a strong association with later illegal drug use in our population (Brook et al., 2002; Lewinsohn et al., 1999). We found adolescent regular smoking to be significantly associated with all drug use and abuse problems, except for heroin use at age 42, which may be due to the much smaller prevalence of recent heroin use in our population (6%). One study that looked at ethnic differences for the association between early smoking and later illegal drug use found that for African Americans, early smoking was related to later marijuana use, but not related to other drug abuse or dependence problems (Vega & Gil, 2005). The prevalence of drug abuse problems in that study, however, was much lower than in our study population (2.7% vs. 18%) and the follow-up age was only to age 20. Given the evidence in the literature that African Americans are more likely to use marijuana before cigarette smoking (Vaughn et al., 2008), it is possible that marijuana has a stronger association to later illegal drug use problems than cigarette smoking in this population. More studies are needed with samples of ethnic minorities to examine the role of the social environment in the mechanism of drug progression. Even though the gateway hypothesis of cigarettes was supported in our study population, future studies should examine other hypotheses to explain the correlation of multiple drug use, considering populations with various drug-using prevalence, socioeconomic status, and ethnic backgrounds.

We found evidence for the mediating role of educational attainment in the progression from adolescent smoking to illegal drug use, including marijuana, cocaine use and drug abuse, and dependence problems. Adolescents who smoke cigarettes may elicit a social control response and then engage in more deviant behaviors, such as dropping out of school (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). Our study shows that lower educational attainment increases the likelihood of illegal drug use in adulthood. Mediation analysis provides insights to develop programs for drug prevention by identifying factors that can be altered to change the outcomes (MacKinnon, 2008). Educational attainment is a key intervention factor to interrupt drug progression from cigarette smoking. School-based interventions have been used for preventing illegal drug use among adolescents (Botvin, Scheier, & Griffin, 2001; Faggiano et al., 2008; Kellam et al., 2008); however, school-based interventions are at risk of not reaching the high-risk 16-year-and-older population due to the high dropout rate. It is important to develop intervention programs outside of the school setting, targeting this population in transition from adolescence to young adulthood that continue other deviant behaviors after using cigarettes. Alternatively, since younger children are more likely to be in school, school-based interventions should target earlier intervention and not wait until adolescence. Early school-based interventions targeting first and second graders, such as Good Behavior Game intervention—a universal classroom behavior management method tested in first and second grade classrooms—have proven to be effective in reducing drug and alcohol abuse/dependence disorders and regular smoking in young adulthood for males (Kellam et al., 2008; Kellam et al., 2011). The purpose for this intervention was to create a classroom environment conducive to learning for all students and focused on the social context of the classroom. With a process of behavior-contingent reinforcement, students learn to regulate their classmates’ and their own behavior. The goal was to reduce early aggressive and disruptive behaviors as antecedent behavior of future adverse outcomes. Teamed-up students were rewarded if they had less infractions of acceptable student behavior, which was stated in the basic classroom rules posted by teachers (Kellam et al., 2008; Kellam et al., 2011). Such an intervention provided teachers with better tools to help students be socialized into the role of student and emphasized the role of the school environment (Kellam et al., 2008; Kellam et al., 2011).

We did not find evidence supporting the mediating role of educational attainment in the association between adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol abuse problems. A potential explanation for this may lie in the fact that the association between education and alcohol use or abuse is not as conclusive as the association between education and other substance use (Crum et al., 2006; Huerta & Borgonovi, 2010). One review looked at the association of early-life socioeconomic status with later drug use (Daniel et al., 2009). They found that there was support for an association of childhood disadvantage with illegal drugs, especially marijuana use, but they did not find consistent, significant association for later alcohol use or abuse. A longitudinal study used a community sample of young adults in France followed since 1991 to 2009 and found that associations between socioeconomic characteristics and substance use differed by substance. Except for alcohol abuse, people with lower socioeconomic status were more likely to use psychoactive substances (Redonnet, Chollet, Fombonne, Bowes, & Melchior, 2012). The pathway from early cigarette smoking to later alcohol abuse may be mediated by factors other than educational attainment. Human and animal studies suggest that nicotine increased the likelihood of the rewarding effects of alcohol and prolongs the motivation to consume it (Barrett, Tichauer, Leyton, & Pihl, 2006; Kristjansson et al., 2012). When exploring the mechanism of the pathway from cigarette smoking to alcohol abuse, future studies should include other factors, such as drinking motive.

Our study has a few limitations. Our study population is a population of urban African Americans; hence, the results may not be generalizable and may have limited applicability to other populations. Drug-using behaviors may need to be defined differently in various populations. Our measurements of smoking behavior and illegal drug use were based on self-reported data; we do not know whether there would be self-report bias due to differences between the group that smoked regularly in adolescence and those who did not. Last, even though propensity score matching helped reduce selection bias, we still cannot adjust for unobserved confounders, such as genetic origins of addiction. Nicotine and most illegal drug addiction can be attributed to genetic influences, and there might be an overlap in the genetic influences on these addictions (Agrawal et al., 2012). One study showed that nicotine dependence shared 37% of heritable variation with alcohol and illegal drugs (Agrawal et al., 2012; Kendler, Myers, & Prescott, 2007). We provided evidence for the gateway hypothesis of early cigarette use on any illegal drug using the propensity score matching method, but there needs to be more evidence to establish the causation. Lastly, the present study did not aim to evaluate the role of other theories of vulnerability and progression of drug use that have been discussed in the scientific literature, such as the “common liability” and the “route administration” models (Rabin & George, 2015). These models can be integrated with the “gateway theory” to create a more comprehensive etiological model to explain experimentation with drugs and drug use disorders in future work.

After using propensity score matching to reduce selection bias, adolescent cigarette smoking showed significant gateway association for drug progression in young- and mid-adulthood. We confirmed the importance of viewing adolescent cigarette smoking as a signaling behavior for drug progression in adulthood. Our study also showed that educational attainment is a mediator in the pathway of early cigarette smoking to later illegal drug use, and abuse or dependence problems, but not to alcohol abuse problems. More focus needs to be put on high school dropout and development of interventions in community settings or earlier in the life course than adolescence to alter the pathway for drug progression for adolescents who use cigarettes regularly. Besides the person-level educational attainment that we examined in our study, future studies are needed to expand their exploration of various aspects of the mechanisms in the drug progression pathway.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grant number R01-DA06630].

Glossary

- Gateway hypothesis

Drug use has various and sequential developmental stages, and that people who use drugs are at risk but do not inevitably progress into another type of drug. The stages of drug use development begins with legal drugs— cigarettes or alcohol—and then progress to illegal drug: first marijuana and then to other illegal drugs, such as cocaine and heroin

- Propensity score matching method

The propensity score matching method was used to select a treatment group and a nontreatment group that have similar distributions of observed covariates in observational studies. Traditional regression analysis yields bias estimates when the two comparison groups have very different multivariate distribution, while propensity score matching relies less on extrapolation and model-based assumptions

Biographies

Carol Strong is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Public Health at the National Cheng Kung University in Taiwan. She was trained at the Department of Health, Behavior and Society at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health for her master’s and doctoral degrees. Her research interests include cancer prevention among Asian Americans, adolescent health and HIV prevention. Her recent work examines the long-term impact of childhood family adversity and potential protecting mechanisms in adolescents’ developmental phase in Taiwan, a project funded by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology. She is also working on analyzing patterns of sexually transmitted infections in a large sample of HIV-infected individuals.

Hee-Soon Juon is a Professor at the Department of Medical Oncology at the Thomas Jefferson University. Dr. Juon has been working as a co-investigator of the Woodlawn Project since 1995. Her research interests also include cancer prevention among Asian Americans. She is the principal investigator for several Nation Cancer Institute-funded projects, such as Asian American Liver Cancer Education Program, and Lay Health Advisor Intervention to Reduce Cancer Disparity.

Margaret E. Ensminger is the Vice Chair of the Department of Health, Behavior and Society at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her interests include life span development and health; poverty and health; childhood and adolescence; social structure and health; substance use; aggressive and violent behavior. She is the principal investigator of the Woodlawn project, in which she has been following a cohort of children from an inner city neighborhood, first seen when they were in first grade. They have been assessed at age 42. Their mothers were interviewed for a third time as they are about at retirement age. She and her colleagues have been examining the early individual, family and neighborhood antecedents to both healthy and unhealthy outcomes for the cohort of former first graders and their mothers.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

ORCID

Carol Strong http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2934-5382

References

- Agrawal A, Verweij KJ, Gillespie NA, Heath AC, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Martin NG, Lynskey MT. The genetics of addiction-a translational perspective. Translational Psychiatry. 2012;2:e140. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the national comorbidity survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1994;2(3):244–268. [Google Scholar]

- Austin PC. A critical appraisal of propensity-score matching in the medical literature between 1996 and 2003. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27(12):2037–2049. doi: 10.1002/sim.3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ. Working class matters: Socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(2):269–278. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SP, Tichauer M, Leyton M, Pihl RO. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration in non-dependent male smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81(2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.009. doi:S0376–8716(05)00216-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Wilens TE, Fontanella JA, Poetzl KM, Faraone SV. Is cigarette smoking a gateway to alcohol and illicit drug use disorders? A study of youths with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59(3):258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GF, Scheier LM, Griffin KW. Preventing the onset and developmental progression of adolescent drug use: Implications for the gateway hypothesis. In: Kandel DB, editor. Stages and pathways of drug involvement: Examining the gateway hypothesis. 2001. pp. 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1039–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin JB, Galati JC, Royston P. A new framework for managing and analyzing multiply imputed data in stata. Stata Journal. 2008;8(1):49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Castaldelli-Maia JM, Nicastri S, Garcia de Oliveira L, Guerra de Andrade A, Martins SS. The role of first use of inhalants within sequencing pattern of first use of drugs among Brazilian university students. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22(6):530–540. doi: 10.1037/a0037794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Unger JB, Palmer P, Weiner MD, Johnson CA, Wong MM, Austin G. Prior cigarette smoking initiation predicting current alcohol use: Evidence for a gateway drug effect among California adolescents from eleven ethnic groups. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(5):799–817. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. The syndrome of minimal brain dysfunction: Psychological aspects. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 1967;14(4):749–766. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)32053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Juon HS, Green KM, Robertson J, Fothergill K, Ensminger M. Educational achievement and early school behavior as predictors of alcohol-use disorders: 35-year follow-up of the woodlawn study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(1):75–85. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel JZ, Hickman M, Macleod J, Wiles N, Lingford-Hughes A, Farrell M, Lewis G. Is socioeconomic status in early life associated with drug use? A systematic review of the evidence. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2009;28(2):142–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2008.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Chiu WT, Medina-Mora ME, Neumark Y, Sampson N, Dierker WT. Evaluating the drug use “gateway” theory using cross-national data: Consistency and associations of the order of initiation of drug use among participants in the WHO world mental health surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108(1–2):84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Tellez M, Finlayson TL, Gretebeck KA, Siefert K, Williams DR, Ismail AI. Cigarette smoking among low-income African Americans: A serious public health problem. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29(3):218–220. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty EE, Green KM, Ensminger ME. Investigating the long-term influence of adolescent delinquency on drug use initiation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93(1–2):72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty EE, Green KM, Reisinger HS, Ensminger ME. Long-term patterns of drug use among an urban african-american cohort: The role of gender and family. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2008;85(2):250–267. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9246-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance–united states, 2007. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries : Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries/CDC. 2008;57(4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. High-risk behaviors associated with early smoking: Results from a 5-year follow-up. The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2001;28(6):465–473. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faggiano F, Vigna-Taglianti FD, Versino E, Zambon A, Borraccino A, Lemma P. School-based prevention for illicit drugs use: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine. 2008;46(5):385–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME. Childhood and adolescent antecedents of drug and alcohol problems: A longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82(1):61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME, Green KM, Crum RM, Robertson J, Juon HS. The impact of early school behavior and educational achievement on adult drug use disorders: A prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92(1–3):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Abrams DB, Buka SL. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: Initiation, regular use, and cessation. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57(10):802–808. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. Substance use progression and hard drug use in inner-city New York. In: Kandel DB, editor. Stages and pathways of drug involvement: Examining the gateway hypothesis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 90–114. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT, Agrawal A, Duncan AE, Haber JR, Bucholz KK. Associations of alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and drug use/dependence with educational attainment: Evidence from cotwin-control analyses. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(8):1412–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01752.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Doherty EE, Stuart EA, Ensminger ME. Does heavy adolescent marijuana use lead to criminal involvement in adulthood? evidence from a multiwave longitudinal study of urban African Americans. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;112(1–2):117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Ensminger ME. Adult social behavioral effects of heavy adolescent marijuana use among African Americans. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(6):1168– 1178. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Barth RP, Gibbons C. Propensity score matching strategies for evaluating substance abuse services for child welfare clients. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28(4):357–383. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Fraser MW. Propensity score analysis: Statistical methods and applications. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harder VS, Stuart EA, Anthony JC. Adolescent cannabis problems and young adult depression: Male-female stratified propensity score analyses. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;168(6):592–601. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haviland A, Nagin DS, Rosenbaum PR, Tremblay RE. Combining group-based trajectory modeling and propensity score matching for causal inferences in nonexperimental longitudinal data. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(2):422–436. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis. 2007;15(3):199–236. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpl013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta MC, Borgonovi F. Education, alcohol use and abuse among young adults in Britain. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2010;71(1):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis B, Graham H, Manor O, Power C. Cigarette consumption and socio-economic circumstances in adolescence as predictors of adult smoking. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2003;98(12):1765–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Juon HS, Ensminger ME, Feehan M. Childhood adversity and later mortality in an urban African American cohort. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(12):2044– 2046. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juon HS, Ensminger ME, Sydnor KD. A longitudinal study of developmental trajectories to young adult cigarette smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;66(3):303–314. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D. Stages and pathways of drug involvement: Examining the gateway hypothesis. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Branch JD, Agrawal KC, Ensminger ME. Mental health and going to school: The woodlawn program of assessment, early intervention, and evaluation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Brown CH, Poduska JM, Ialongo NS, Wang W, Toyinbo P, Wilcox HC. Effects of a universal classroom behavior management program in first and second grades on young adult behavioral, psychiatric, and social outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95(Suppl 1):S5–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Mackenzie AC, Brown CH, Poduska JM, Wang W, Petras H, Wilcox HC. The good behavior game and the future of prevention and treatment. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2011;6(1):73–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA. Specificity of genetic and environmental risk factors for symptoms of cannabis, cocaine, alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(11):1313–1320. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.11.1313. doi:64/11/1313 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel KG. Ten largest racial and ethnic health disparities in the united states based on healthy people 2010 objectives. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;166(1):97– 103. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjansson SD, Agrawal A, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Madden PA, Cooper ML, Bucholz KK, Heath AC. The relationship between rs3779084 in the dopa decarboxylase (DDC) gene and alcohol consumption is mediated by drinking motives in regular smokers. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(1):162–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Huang Y, Drisaldi B, Griffin EA, Jr, Pollak DD, Xu S, Kandel ER. Molecular mechanism for a gateway drug: Epigenetic changes initiated by nicotine prime gene expression by cocaine. Science Translational Medicine. 2011;3(107):107ra109. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Brown RA. Level of current and past adolescent cigarette smoking as predictors of future substance use disorders in young adulthood. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 1999;94(6):913–921. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94691313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry R, Kann L, Collins JL, Kolbe LJ. The effect of socioeconomic status on chronic disease risk behaviors among US adolescents. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276(10):792–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Applications of the mediation model. In: MacKinnon DP, editor. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York & London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, McKean J, Kosten S, Tonigan JS. A novel application of propensity score matching to estimate alcoholics anonymous’ effect on drinking outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;129(1–2):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers M, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF, Williams J, Patton GC. Consequences of youth tobacco use: A review of prospective behavioural studies. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2006;101(7):948–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melotti R, Heron J, Hickman M, Macleod J, Araya R, Lewis G, ALSPAC Birth Cohort Adolescent alcohol and tobacco use and early socioeconomic position: The ALSPAC birth cohort. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):e948–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. The economic costs of drug abuse in the united states, 1992–2002. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President; 2004. (No. Publication No. 207303). [Google Scholar]

- Perkins AW, Forehand MR. Implicit self-referencing: The effect of nonvolitional self-association on brand and product attitude. Journal of Consumer Research. 2012;39(1):142–156. doi: 10.1086/662069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin RA, George TP. A review of co-morbid tobacco and cannabis use disorders: Possible mechanisms to explain high rates of co-use. The American Journal on Addictions/American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions. 2015;24(2):105–116. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redonnet B, Chollet A, Fombonne E, Bowes L, Mel-chior M. Tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and other illegal drug use among young adults: The socioeconomic context. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121(3):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter J. Using statistics to determine causal relationships. The American Mathematical Monthly. 2000;107:24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Services & Outcomes Research Methodology. 2001;2:169– 188. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 10. College Station TX: StataCorp LP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman FA, Bone L, Avila-Tang E, Smith K, Yancey N, Street C, Owings K. Barriers to smoking cessation in inner-city african american young adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(8):1405–1408. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong C, Juon HS, Ensminger ME. Long-term effects of adolescent smoking on depression and socioeconomic status in adulthood in an urban african american cohort. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2014;91(3):526–540. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9849-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart EA, Green KM. Using full matching to estimate causal effects in nonexperimental studies: Examining the relationship between adolescent marijuana use and adult outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(2):395–406. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart EA, Rubin DB. Best practices in quasi-experimental designs. In: Osborne J, editor. Best practices in quantitative social science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. pp. 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. (No NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No (SMA) 13–4795). [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake DS, Huh J, Lakon CM. Use of propensity score matching in evaluating smokeless tobacco as a gateway to smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2009;11(4):455–462. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43(3):692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Trends in the prevalence of selected risk behaviors and obesity for black students national YRBS: 1991–2009. 2010a Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/us_summary_black_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Trends in the prevalence of selected risk behaviors and obesity for white students national YRBS: 1991–2009. 2010b Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/us_summary_white_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Trends in the prevalence of tobacco use: National YRBS 1991—2013. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_tobacco_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- van Nimwegen FA, Penders J, Stobberingh EE, Postma DS, Koppelman GH, Kerkhof M, Thijs C. Mode and place of delivery, gastrointestinal microbiota, and their influence on asthma and atopy. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;128(5):948–55. e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn M, Wallace J, Perron B, Copeland V, Howard M. Does marijuana use serve as a gateway to cigarette use for high-risk African-American youth? The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34(6):782–791. doi: 10.1080/00952990802455477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG. Revisiting drug progression: Long-range effects of early tobacco use. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2005;100(9):1358–1369. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EM, Wolf DA. Mixed results in a transitional planning program for alternative school students. Evaluation Review. 2008;32(2):187–215. doi: 10.1177/0193841×07310600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Lynch J, Schulenberg J, Roux AV, Raghunathan T. Emergence of socioeconomic inequalities in smoking and overweight and obesity in early adulthood: The national longitudinal study of adolescent health. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(3):468–477. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]