Abstract

AIM

To investigate any changing trends in the etiologies of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Argentina during the last years.

METHODS

A longitudinal cohort study was conducted by 14 regional hospitals starting in 2009 through 2016. All adult patients with newly diagnosed HCC either with pathology or imaging criteria were included. Patients were classified as presenting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) either by histology or clinically, provided that all other etiologies of liver disease were ruled out, fatty liver was present on abdominal ultrasound and alcohol consumption was excluded. Complete follow-up was assessed in all included subjects since the date of HCC diagnosis until death or last medical visit.

RESULTS

A total of 708 consecutive adults with HCC were included. Six out of 14 hospitals were liver transplant centers (n = 484). The prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 27.7%. Overall, HCV was the main cause of liver disease related with HCC (37%) including cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients, followed by alcoholic liver disease 20.8%, NAFLD 11.4%, cryptogenic 9.6%, HBV 5.4% infection, cholestatic disease and autoimmune hepatitis 2.2%, and other causes 9.9%. A 6-fold increase in the percentage corresponding to NAFLD-HCC was detected when the starting year, i.e., 2009 was compared to the last one, i.e., 2015 (4.3% vs 25.6%; P < 0.0001). Accordingly, a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus was present in NAFLD-HCC group 61.7% when compared to other than NAFLD-HCC 23.3% (P < 0.0001). Lower median AFP values at HCC diagnosis were observed between NAFLD-HCC and non-NAFLD groups (6.6 ng/mL vs 26 ng/mL; P = 0.02). Neither NAFLD nor other HCC etiologies were associated with higher mortality.

CONCLUSION

The growing incidence of NAFLD-HCC documented in the United States and Europe is also observed in Argentina, a confirmation with important Public Health implications.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Etiology, Fatty liver, South America

Core tip: Despite the increasing incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and NAFLD related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in developed countries, information related with the burden of NAFLD-HCC in developing countries as those in South America is lacking. In this multicenter cohort study from Argentina including patients with HCC, while HCV and alcoholic related cirrhosis were the most frequent causes of HCC between 2009 and 2016, NAFLD-HCC had a 6-fold increased during the same period. This changing scenario was observed without precluding any specific etiology of liver disease. NAFLD might become one of the first HCC related causes in the coming decades; an issue to be consider with effective prevention strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer related death worldwide and the main cause of death among patients with cirrhosis[1,2]. The incidence of HCC varies according to geographic location, closely linked to the prevalence of chronic hepatitis C (HCV) or B virus (HBV) infections as well as the prevalence of alcoholic liver disease.

With the advent of new direct antiviral drugs (DAAs) for HCV treatment, epidemiological changes have been reported in the natural history of liver disease[3]. First, the improvement of decompensated cirrhotic patients, the consequence and the increasing rate of delisting from liver transplantation (LT) waitlist after eradication of HCV. On the other hand, a lower wait-listing ratio of patients with HCV decompensated cirrhosis has been observed[3]. However, the proportion of patients listed for LT with HCC has been increased during the era of DAAs[4].

This increasing incidence of HCC has been attributed in developed countries due to a stepwise increase in the incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), recognized as an emergent cause of end stage liver disease and HCC[4,5]. NAFLD is the expression of a pandemic disease, which is associated with the metabolic syndrome, obesity and type 2 diabetes. Indeed, it is estimated that during the next 20 years, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), the progressive form of NAFLD, will constitute the most frequent cause of cirrhosis and HCC in developed countries[6].

However, HCC epidemiological reports from developing areas, including South America, have been heterogeneous[7-14]. Furthermore, no studies have tackled the issue of changing trends in etiologies of HCC over time. Our present aim was to evaluate changes in etiology of HCC in Argentina during the last seven years, focusing on two aspects, the potential changes associated with DAA’s era of HCV treatment, as well as changes associated with NAFLD-HCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This longitudinal observational cohort study was conducted between January 1 2009 and January 1 2016 in 14 regional hospitals from Argentina. Sites were instructed to enroll all eligible patients on a sequential basis and data to be recorded from medical charts into a web-based electronic system.

A cohort of consecutive adult patients (> 17 years of age) with newly diagnosed HCC was included. Criteria for inclusion required patients to have newly diagnosed HCC either by pathological criteria or imaging evaluation as recommended by international guidelines[15,16].

Etiologies of HCC considering the primary diagnosis of liver disease included HCV (anti HCV positivity), HBV (hepatitis B surface antigen positivity), alcoholic liver disease (alcohol intake exceeding 30 g), NAFLD, cryptogenic cirrhosis (CC), cholestatic liver diseases (i.e., primary biliary cholangitis, primary and secondary sclerosing cholangitis), autoimmune hepatitis and other causes including metabolic diseases or miscellaneous causes (e.g., hereditary hemochromatosis, Wilson disease, toxic liver disease).

NAFLD diagnosis was achieved on histological ground or clinically according to international guidelines[17]. Patients were classified as presenting clinical NAFLD provided that all other etiologies of liver disease were ruled out, fatty liver was present on abdominal ultrasound (US) and alcohol consumption was excluded (30 g for men and 20 g women). Histological NAFLD was defined by an excessive hepatic fat accumulation associated with insulin resistance and the presence of > 5% of steatosis in liver biopsy. NAFLD included non-alcoholic fatty liver and NASH.

Baseline patient and tumor characteristics were recorded at HCC diagnosis including patients demographics, previous US surveillance, performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ECOG grade 0-4)[18], liver fibrosis stage (I-IV) assessed by liver biopsy elastography, other non-invasive measurements or by clinical data (presence of esophageal varices or ascites or splenomegaly > 120 mm diameter, or features related to portal hypertension), Child Pugh score and laboratory variables. Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels at diagnosis were categorized in three cut-off values: ≤ 100 ng/mL, 101-1000 ng/mL and > 1000 ng/mL[19].

Specific major co-morbidities for each subject were also registered including: diabetes mellitus, severe chronic pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease and congestive heart disease, previous ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney failure (glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min) and non-HCC cancer.

Tumor characteristics and treatments performed during follow-up were also registered. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance images (MRI) were included to assess tumor burden, which was classified according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging (BCLC criteria)[16].

Study end-points

Our study focused on changing trends of HCC etiologies at different periods from 2009 to 2016. A stratified per-etiology analysis and per Liver Transplant (LT) and non-LT centers was performed. Complete patient follow-up was assessed in all included subjects from HCC diagnosis until death or last medical visit.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines[20]. This study was approved by the Austral University School of Medicine and by all 14 centers; complied with the ethical standards (institutional and national) and with Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Patient consent was obtained in all subjects included.

Statistical analysis

Institutional clinical research committee reviewed the statistical methods of this study. Categorical data were compared using Fisher’s exact test (2-tailed) or χ2 test. Continuous variables were compared with Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test according to their distribution, respectively. For survival analysis, Cox regression multivariate analysis estimating hazard ratios (HR) and 95%CI for baseline variables related with 5-year mortality was performed. Confounding effect was defined when more than 20% of change in the crude HR. Kaplan Meier survival curves were compared using the log-rank test (Mantel-Cox) and adjustment of each final model was evaluated with proportional hazards through graphic and statistical evaluation (Schoenfeld residual test). Calibration was assessed by comparison of observed and predicted curves and evaluation of the goodness of fit of the model by Harrell’s c-statistic index. Collected data was analyzed using STATA 10.0.

RESULTS

A total of 708 consecutive adult patients with newly diagnosed HCC from 14 centers were included. Out of 14 hospitals, 6 were LT centers, which contributed with the follow-up of 484 patients (68.4% of the study cohort).

Baseline patients and tumor characteristics

Table 1 describes the baseline patients’ characteristics. Non-cirrhotic patients accounted for 12.6% of the included cohort (n = 89). Overall prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DBT) was 27.7% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ baseline characteristics

| Variable | P values |

| Age, yr (± SD) | 62 ± 10 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 537 (75.9) |

| Non-cirrhotic liver, n (%) | 89 (12.6) |

| Child Pugh A/B/C, n (%) | 352 (49.7)/238 (33.6)/118 (16.7) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 299 (42.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 196 (27.7) |

| Ascites, n (%) | 253 (35.7) |

| Mild | 144 (20.3) |

| Moderate-severe | 109 (15.4) |

| Encephalopathy, n (%) | 147 (20.8) |

| Grade I-II | 137 (19.3) |

| Grade III-IV | 10 (1.4) |

| Esophageal varices, n (%) | 394 (56.7) |

| ECOG 0-2/3-4, n (%) | 637 (89.9)/71 (10.1) |

| Median HCC number, (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) |

| Largest HCC diameter, mm (IQR) | 53 ± 37 |

| Within Milan, n (%) | 334 (46.9) |

| Bilobar involvement, n (%) | 159 (22.1) |

| Diffuse HCC pattern, n (%) | 28 (3.9) |

| Median AFP, ng/mL (IQR) | 23.0 (5.0-337.0) |

| ≤ 100 ng/mL, n (%) | 476 (66.3) |

| 101-1000 ng/mL, n (%) | 128 (17.7) |

| > 1000 ng/mL, n (%) | 115 (16.0) |

| Tumor vascular invasion, n (%) | 74 (10.4) |

| Extrahepatic disease, n (%) | 48 (6.8) |

ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein.

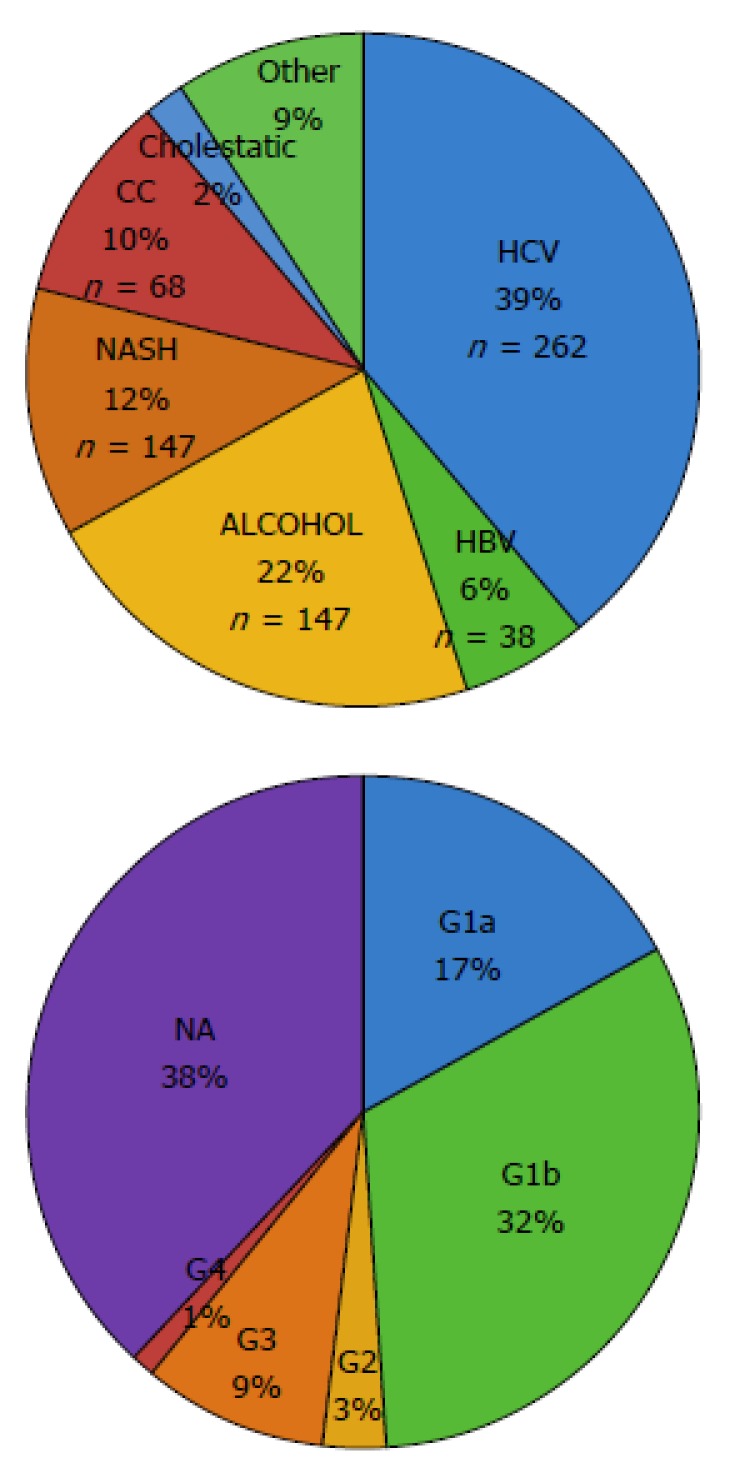

Overall, HCV was the most frequent cause of underlying liver disease. Etiology of HCC in cirrhotic patients was as follows: 37% HCV infection (n = 262), 20.8% alcoholic liver disease (n = 147), 11.4% NAFLD (n = 81), 9.6% cryptogenic cirrhosis/liver disease (CC, n = 68), 5.4% HBV infection (n = 38), 2.2% of cholestatic disease and autoimmune hepatitis (n = 16), and 9.9% other causes (n = 60) (Table 2). Most frequent HCV genotypes (G) were G1b (n = 88), followed by G1a (n = 47), G3 (n = 27), G2 (n = 8) and G4 (n = 2) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Underlying etiologies of liver disease per year (frequencies)

| HCV | HBV | Alcohol | NASH | CC | Cholestasis | AI | Other1 | Total | |

| 2009 | 24 (34.3) | 7 (10.0) | 18 (25.7) | 3 (4.3) | 9 (12.9) | 0 | 0 | 9 (12.9) | 70 |

| 2010 | 51 (48.6) | 5 (4.8) | 16 (15.2) | 5 (4.8) | 12 (11.4) | 3 (2.9) | 1 (0.9) | 12 (11.5) | 105 |

| 2011 | 34 (35.6) | 5 (5.3) | 26 (27.4) | 10 (10.5) | 9 (9.5) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 7 (6.4) | 95 |

| 2012 | 43 (38.0) | 5 (4.4) | 21 (18.6) | 14 (12.4) | 10 (8.8) | 3 (2.6) | 0 | 5 (8.0) | 113 |

| 2013 | 43 (33.1) | 9 (6.9) | 24 (18.5) | 14 (10.8) | 17 (13.1) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) | 13 (10.0) | 130 |

| 2014 | 43 (36.7) | 4 (3.4) | 22 (18.8) | 15 (12.8) | 9 (7.7) | 3 (2.6) | 0 | 16 (13.7) | 117 |

| 2015 | 24 (30.8) | 3 (3.8) | 20 (25.6) | 20 (25.6) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 4 (5.2) | 78 |

| Total (%) | 262 (37.0) | 38 (5.4) | 147 (20.8) | 81 (11.4) | 68 (9.6) | 13 (1.8) | 3 (0.4) | 60 (9.9) | 708 |

Other causes of cirrhosis, Hemochromatosis. NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; AI: Autoimmune; CC: Cryptogenic cirrhosis; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Figure 1.

Etiologies oh hepatocellular carcinoma in the overall cohort and hepatitis C virus genotypes. HCV was the main cause of liver disease related with hepatocellular carcinoma including cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients. Distribution of known HCV genotypes (G) showed that G1b was the most frequent (n = 88), followed by G1a (n = 47), G3 (n = 27), G2 (n = 8) and G4 (n = 2). HCV: Hepatitis C virus.

Etiology of HCC among non-cirrhotic patients included cryptogenic liver disease in 52.8% (n = 47), chronic HCV infection in 21.3% (n = 19), NAFLD in 10.1% (n = 9), chronic HBV infection in 9.0% (n = 8), altered iron metabolism in 4.5% (n = 4) and chronic alcohol consumption in 2 patients.

At HCC diagnosis, 4.2% (n = 30), 43.1% (n = 305), 21.3% (n = 151), 9.5% (n = 67) and 21.9% (n = 155) of the patients were within BCLC 0, A, B, C and D stages, respectively. Median serum AFP was 23.0 ng/mL (IQR 5.0; 337 ng/mL, Table 1).

Etiologies of HCC stratified by periods of time

Changes over time for each HCC etiology were analyzed in order to observe any epidemiological changes during the entire period. HCV related HCC was the most frequent etiology along the whole observation period. No significant changes were observed in the proportion of HCV-HCC (Table 2). The second most frequent cause of HCC was alcoholic liver disease, remaining stable during the observation period. On the other hand, a striking 6-fold increase in the proportion of HCC-NAFLD cases was observed since 2009 to 2016 (4.3% vs 25.6%; P < 0.0001). Moreover, NAFLD represented the second cause of HCC in 2015 together with alcoholic liver disease (Table 2).

We further considered patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis and DBT (n = 22/68) as potentially NAFLD. This new group was merged with NAFLD accounting for 14.5% (n = 103) of the entire cohort. Its incidence increased from 8.6% in 2009 to 16.2% in 2014 and 25.6% in 2016, respectively (P = 0.014). Prevalence of DBT was similar between HCC cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients (23.2% vs 28.2%; P = 0.38).

Comparative analysis between NAFLD and non-NAFLD HCC patients

A comparative analysis between NAFLD and non-NAFLD-HCC was performed. Mean age was similar in both groups. Only a small proportion of patients were non-cirrhotic (8.6% NAFLD vs 9.9% non-NAFLD; P = 0.72). There were no significant differences regarding Child Pugh score, MELD score and presence of clinically significant portal hypertension (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative analysis between non alcoholic fatty liver disease and other than non alcoholic fatty liver disease

| Variable | NAFLD n = 81 (11.4%) | Non-NAFLD n = 627 (88.6%) | P value |

| Age, yr (± SD) | 63 ± 8 | 62 ± 4 | 0.39 |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 68 (83.9) | 469 (74.9) | 0.06 |

| Non-cirrhotic liver, n (%) | 7 (8.6) | 62 (9.9) | 0.72 |

| Child Pugh A/B/C, n (%) | 41 (50.6)/32 (39.5)/8 (9.9) | 311 (49.6)/206 (32.8)/110 (17.5) | 0.15 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 60 (74.1) | 239 (38.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 50 (61.7) | 146 (23.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Median AFP level, ng/mL | 6.6 (4-380) | 26 (5.3-332) | 0.017 |

| AFP > 1000 ng/mL, n (%) | 9 (12.0) | 97 (16.1) | 0.34 |

| Ascites, n (%) | |||

| Mild | 17 (21.0) | 127 (20.3) | 0.7 |

| Moderate-severe | 10 (12.3) | 99 (15.8) | 0.7 |

| Encephalopathy, n (%) | |||

| Grade I-II | 18 (22.2) | 119 (19.0) | 0.2 |

| Grade III-IV | 3 (3.7) | 7 (1.1) | 0.2 |

| Esophageal varices, n (%) | 50 (63.3) | 344 (55.8) | 0.5 |

| ECOG 0-2, n (%) | 73 (90.1) | 564 (89.9) | 0.96 |

| Median HCC number, (IQR) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 0.38 |

| Largest HCC diameter, mm (IQR) | 55 ± 37 | 52 ± 37 | 0.51 |

| Within Milan, n (%) | 38 (46.9) | 295 (47.0) | 0.98 |

| Bilobar involvement, n (%) | 16 (19.7) | 142 (22.7) | 0.82 |

| Diffuse HCC pattern, n (%) | 3 (3.7) | 20 (3.2) | 0.82 |

AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; MELD: Model for end stage liver disease; AFLD: Alcoholic fatty liver disease; Non-NAFLD: Other than NAFLD (includes all other etiologies).

Comorbidities were most frequently observed in the NAFLD group, particularly there was a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DBT) (61.7% vs non-NAFLD 23.3%; P < 0.0001). When a stratified analysis was performed comparing the prevalence of DBT, there were no changes observed ranging from 8.9% in 2009 to 17.3% in 2012 (P = 0.89). As previously shown, the increasing proportion of NAFLD in the overall cohort was not in parallel with an increasing prevalence of DBT.

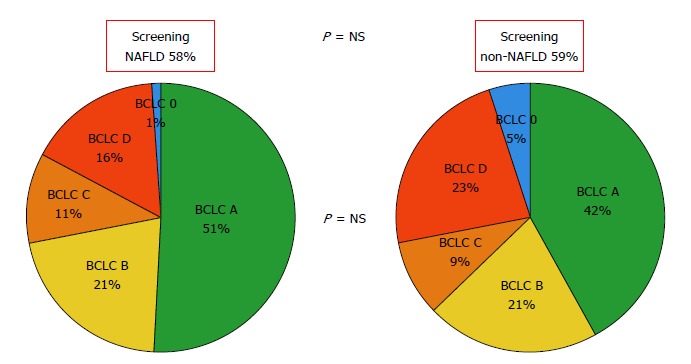

Regarding HCC burden, there were no significant differences with previous surveillance (NAFLD 59.5% vs non-NAFLD 57.9%; P = 0.81) and BCLC staging at HCC diagnosis. Median AFP was lower in the NAFLD-HCC when compared to non-NAFLD group (6.6 ng/mL vs 26 ng/mL; P = 0.02) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis regarding hepatocellular carcinoma previous surveillance and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging at diagnosis between non alcoholic fatty liver disease and other etiologies of liver disease. NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Non-NAFLD: Other than NAFLD (includes all other etiologies).

Etiology of HCC in non-liver transplant vs liver transplant centers

Among LT centers, the main etiology of HCC during 2009 was HCV, remaining stable over the years, becoming the second cause of HCC in 2015. Furthermore, the main cause of HCC during 2015 was NAFLD, showing 6-fold increase from 2009 to 2014 and 2015 (5.8% vs 13.9% vs 36.9%, respectively; P < 0.0001). Alcoholic liver disease was the second overall cause of HCC, which was unchanged since 2009 among the different periods.

In non-transplant centers, HCV was the most frequent cause of HCC during all analyzed periods, followed by alcoholic liver disease. No significant changes in the proportion of patients with HCV or alcoholic liver disease were observed in this group. An increasing number of NAFLD-HCC cases were observed, which was lower than that observed in LT centers (LT centers 5.8% to 36.9%; P < 0.0001 vs non-LT centers 0% to 9%; P = NS).

Etiologies and impact on patient survival

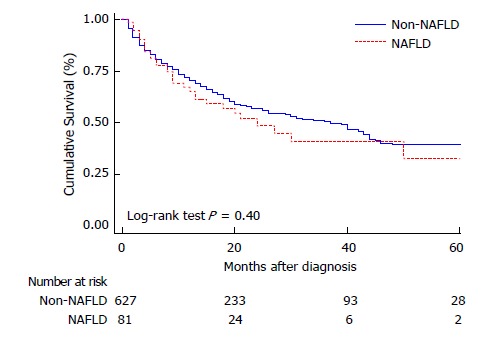

Both uni and multivariate Cox regression analysis were performed as shown on Table 4 evaluating baseline patient and HCC characteristics associated with worse survival. Neither the presence of comorbidities (HR 1.08; CI 0.86; 1.37) nor DBT were related to mortality (HR 0.83; CI 0.63; 1.08). When considering different HCC etiologies, neither NAFLD nor viral etiologies presented higher mortality rates during the follow-up (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Baseline pre-treatment variables associated with 5-year mortality, univariate cox regression

| Variable | 5-yr mortality rate, (%) | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 1.02 (1.01; 1.04) | < 0.0001 | |

| Gender: male (n = 537) | 42.7 | 1.08 (0.83; 1.42) | 0.58 |

| Female (n = 170) | 42.3 | ||

| Comorbidity | |||

| Yes (n = 299) | 45.1 | 1.08 (0.86; 1.37) | 0.49 |

| No (n = 409) | 40.6 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| Yes (n = 196) | 38.8 | 0.83 (0.63; 1.08) | 0.17 |

| No (n = 512) | 44 | ||

| NAFLD | |||

| Yes (n = 81) | 35.9 | 1.16 (0.81; 1.69) | 0.41 |

| No (n = 627) | 56.9 | ||

| ECOG 0-2 | |||

| Yes (n = 637) | 37.9 | 0.19 (0.14; 0.26) | 0.0001 |

| No (n = 71) | 84.5 | ||

| BCLC 0-A | |||

| Yes (n = 335) | 26 | 0.29 (0.23; 0.38) | 0.0001 |

| No (n = 373) | 57.4 | ||

| Cirrhosis | |||

| Yes (n = 639) | 42.9 | ||

| No (n = 69) | 39.1 | 0.86 (0.58; 1.28) | 0.45 |

| Child Pugh | |||

| A (n = 352) | 34.5 | - | |

| B (n = 238) | 41.6 | 1.38 (1.06; 1.83) | 0.019 |

| C (n = 118) | 68.6 | 3.23 (2.41; 4.34) | 0.0001 |

| Clinically significant portal hypertension | |||

| Yes (n = 484) | 40.2 | 1.22 (0.94; 1.57) | 0.13 |

| No (n = 224) | 43.7 | ||

| AFP > 1000 ng/mL | |||

| Yes (n = 106) | 64.1 | 3.09 (2.31; 4.15) | 0.0001 |

| No (n = 569) | 39.5 | ||

| Tumor vascular invasion | |||

| Yes (n = 74) | 77 | 4.74 (3.48; 6.44) | 0.0001 |

| No (n = 634) | 38.5 | ||

| Extrahepatic tumor disease | |||

| Yes (n = 48) | 70.8 | 3.29 (2.25; 4.81) | 0.0001 |

| No (n = 660) | 40.5 |

Normal Values: Alpha-fetoprotein 0.6-4.4 ng/mL. AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC: Barcelona clinic liver cancer; ECOG: Eastern cooperative oncology group; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; LT: Liver transplantation; WL: Waiting list; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Figure 3.

Comparative survival between non alcoholic fatty liver disease and other etiologies of liver disease. NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; Non-NAFLD: Other than NAFLD (includes all other etiologies).

On the multivariate model, independent variables associated with death were age HR 1.03 (CI 1.01; 1.04), BCLC 0-A stages vs non 0-A stages HR 0.50 (CI 0.37; 0.68), Child Pugh B or C vs A HR 1.54 (CI 1.61; 2.05), HR 2.59 (CI 1.84; 3.66), respectively; AFP > 1000 ng/mL at HCC diagnosis HR 2.09 (CI: 1.52; 2.87) and HCC vascular invasion HR 2.83 (CI: 1.75; 3.53) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate cox regression analysis of risk factors associated with 5-year mortality

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.01; 1.04 | < 0.0001 |

| BCLC 0-A | 0.50 | 0.37; 0.68 | < 0.0001 |

| Child Pugh B1 | 1.54 | 1.61; 2.05 | 0.003 |

| Child Pugh C1 | 2.59 | 1.84; 3.66 | < 0.0001 |

| AFP > 1000 ng/mL | 2.09 | 1.52; 2.87 | < 0.0001 |

| Tumor vascular invasion | 2.84 | 1.75; 3.53 | < 0.0001 |

Compared to Child Pugh A, Harrell’s concordance statistic was 0.76.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge this is the first multicenter cohort study from a South American country evaluating longitudinal changes in etiologies of HCC. This changing etiologic scenario documented in developed countries is replicated in developing ones[4,5]. The documented increase in NAFLD-HCC in our study entails itself a challenging impact on Public Health worth to be considered in developing countries. HCV infection was the main etiology of HCC throughout the entire observation period, including the last two years, at which time DAA’s therapy was available in Argentina (since 2014). Second, as reported in other regions of the world, fatty liver disease was observed as an increasing cause of HCC. The prevalence of DBT was significantly higher in NAFLD-HCC when compared to non-NAFLD patients. Finally, NAFLD-HCC was not associated with a higher mortality rate.

In a recently published multicenter Latin American retrospective cohort study, the main etiologies of HCC were HCV in almost half of the cases, followed by alcoholic liver disease, HBV infection and NAFLD in nine percent[8]. Another multicenter study from this region including HCC LT patients showed that the most frequent cause of HCC was HBV[9]. This discrepancies show that the reported HCC etiology largely reflects country-to-country epidemiological differences. Whereas in Brazil the main etiology has been shown to be HBV, in Argentina the main HCC etiology has been associated with HCV followed by alcoholic liver disease[9,10,21]. However, no previous studies have evaluated etiologic changes longitudinally.

It is already known that in developed countries, a high-fat diet leads to obesity, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and type 2 DBT. Unbalanced hyper-caloric diets, as well as an increasing consumption of sugar containing beverages might lead to a profound Public Health intervention. These socioeconomically changes have been occurring not only in developed but also in developing regions worldwide.

NAFLD has been related to an increasing rate of overall cardiovascular morbid-mortality[6]. Consequently, NAFLD will become responsible of an increase in medical resource use in the next years that demands specific health prevention programs focusing on diet and exercise in order to avoid not only liver but also cardiovascular disease development. As previously mentioned, a six-fold increase in NAFLD from 2009 to 2015 was observed in our cohort, mainly in LT centers whereas alcoholic liver disease was a leading cause of HCC in non-LT centers. This finding has been observed in Argentina by other authors[10].

DBT leads to fibrosis progression, cirrhosis and HCC[6,22,23]. We observed that the increasing prevalence of NAFLD-HCC was not in parallel with the increasing prevalence of DBT over the years. When we included as “potentially NAFLD” those patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis with DBT, a similar 6-fold increase since 2009 to 2015 was observed. Alternatively, we did not considered obese patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis as probable NAFLD as reported by other authors[24]. In our series, body mass index was not recorded. However, we performed a sub analysis considering cryptogenic/DBT patients and NAFLD. Our epidemiological results are in line with that from developed countries, suggesting that NAFLD would have a major Public Health implication in the upcoming years.

Third, from a comparative and specific intergroup variability, there were no differences between non-NAFLD and NAFLD-HCC patients, except from a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus and lower AFP values in NAFLD-HCC group. Interestingly, higher AFP values were described in other studies in this group of patients in comparison to other etiologies[22]. However, this significant difference did not impact on patient survival, although AFP > 1000 ng/mL at HCC diagnosis was an independent predictor of worse survival in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. There were no major differences in HCC tumor burden between NAFLD and non-NAFLD-HCC. Heterogeneous data has been published regarding this topic. Some studies described tumor differences whereas others did not[25,26].

We acknowledge limitations of cohort studies with no control group, in which several factors might be biased. However, a strict revision of the data was centrally requested, investigators who performed the final analysis did not participate in the data collection to avoid differential outcome assessment on exposure and a complete follow-up and outcome assessment was performed in all patients included. Second, the definition of NAFLD was mainly based on clinical assessment. The lack of histological evaluation of NAFLD and NASH in most of the patients might have biased the results. However, this clinical definition is accepted worldwide by international guidelines[17]. Third, an important information or selection bias regarding the lack of body mass index has been mentioned earlier regarding cryptogenic/obese patients. This might have resulted in a lower number of patients in the group of NAFLD reported in our study. Finally, combination of different etiologies (e.g., alcoholic liver disease plus chronic HCV) was not considered in order to include the main factor of chronic liver disease.

In conclusion, NAFLD related HCC has been recognized as a growing burden in the United States and in some European regions. This changing etiologic scenario has been observed in in high-income countries and might even be happening in developing ones. In Argentina, even though HCV infection is still the main cause of HCC, recent changing trends in etiologies of HCC in Argentina suggests that NAFLD might be the leading cause of HCC in the next years, becoming an important Public Health issue. However, prospective studies will be necessary to confirm our findings.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The incidence of Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has been increasing during the last years and is the second leading cause of cancer related death worldwide. The cause of HCC is closely linked to the prevalence of chronic hepatitis C (HCV) or B virus (HBV) infections as well as the prevalence of alcoholic liver disease. With the advent of the new direct antiviral drugs (DAAs) for hepatitis C (HCV) treatment, epidemiological changes have been already reported in the natural history of liver disease. One of these epidemiological changes in developed countries is due to the stepwise increase in the incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), an emergent cause of end stage liver disease and HCC.

Research motivation

Indeed, it is estimated that during the next 20 years, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), the progressive form of NAFLD, will constitute the most frequent cause of cirrhosis and HCC in developed countries. However, reports regarding epidemiological changes of HCC from developing areas, including South America, have been heterogeneous and none have focused on changing trends in etiologies of HCC over time.

Research objectives

Our aim was to evaluate changes in the etiology of HCC in Argentina during the last seven years, particularly focusing on potential changes associated with NAFLD-HCC.

Research methods

This cohort study was conducted between January 1 2009 and January 1 2016 in 14 regional hospitals from Argentina. Criteria for inclusion required patients with newly diagnosed HCC as recommended by international guidelines. Etiologies of HCC included viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease (alcohol intake exceeding 30 g/d), NAFLD, cryptogenic cirrhosis (CC), cholestatic liver diseases (i.e., primary biliary cholangitis, primary and secondary sclerosing cholangitis), autoimmune hepatitis and other causes including metabolic diseases or miscellaneous causes (e.g., hereditary hemochromatosis, Wilson disease, toxic liver disease). NAFLD diagnosis was established on histological ground or clinically according to international guidelines. Baseline patient and tumor characteristics at HCC diagnosis were recorded. Tumor burden was classified according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging (BCLC criteria). Complete patient follow-up was assessed in all included subjects from HCC diagnosis until death or last medical visit.

Categorical data were compared using Fisher’s exact test (2-tailed) or Chi-Square test and continuous variables were compared with Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test according to their distribution, respectively. For survival analysis, Cox regression multivariate analysis estimating hazard ratios (HR) and 95%CI for baseline variables related with 5-year mortality was performed. Kaplan Meier survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Research results

A total of 708 consecutive adult patients with newly diagnosed HCC from 14 centers were included. Out of 14 hospitals, 6 were LT centers, which contributed with the follow-up of 484 patients (68.4% of the study cohort). Non-cirrhotic patients accounted for 12.6% of the included cohort (n = 89). The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DBT) was 27.7%. Between 2009 and 2016, HCV related HCC was the most frequent etiology along the whole observation period. No significant changes were observed in the proportion of HCV-HCC. The second most frequent cause of HCC was alcoholic liver disease, remaining stable along the observation period. On the other hand, a striking 6-fold increase in the proportion of HCC-NAFLD cases was observed since 2009 to 2016 (4.3% vs 25.6%; P < 0.0001). NAFLD was the second cause of HCC in 2015 together with alcoholic liver disease. In addition, when patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis/liver disease and DBT (n = 22/68) were considered together as potentially metabolic syndrome/NAFLD, the NAFLD/Cryptogenic + DBT group represented 14.5% (n = 103) of the entire cohort and increased from 8.6% in 2009 to 16.2% in 2014 and 25.6% in 2016, respectively (P = 0.014). There was a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DBT) (61.7% vs non-NAFLD 23.3%; P < 0.0001) in the NAFLD group. The increasing proportion of NAFLD in the overall cohort was not in parallel with an increase of DBT in this population. On the other hand, lower median AFP values at HCC diagnosis were observed between NAFLD-HCC and non-NAFLD groups (6.6 ng/mL vs 26 ng/mL; P = 0.02). Neither NAFLD nor other HCC etiologies were associated with higher mortality.

Research conclusions

To the best of our knowledge this is the first multicenter cohort study from a South American country evaluating longitudinal changes in etiologic trends. This changing etiologic scenario documented in developed countries is replicated in developing ones. The documented increase in NAFLD-HCC in our study including a developing country entails in itself a challenging impact on Public Health worth to be considered. HCV infection was the main etiology of HCC throughout the entire observation period, including the last two years, at which time DAA’s therapy was available in Argentina. Second, as reported in other regions of the world, fatty liver disease was observed as an increasing cause of HCC. The prevalence of DBT was significantly higher in NAFLD-HCC when compared to non-NAFLD patients. Finally, NAFLD-HCC was not associated with an increasing risk of mortality, adjusted for the presence HCC surveillance and BCLC stage. NAFLD has been related to an increasing rate of overall cardiovascular morbid-mortality. Consequently, NAFLD will become responsible of an increase in medical resource use in the next years that demands specific health prevention programs focusing in diet and exercise in order to avoid not only liver but also cardiovascular disease development. As previously mentioned, a six-fold increase in NAFLD from 2009 to 2015 was observed in our cohort, mainly in LT centers whereas alcoholic liver disease was a leading cause of HCC in non-LT centers.

Research perspectives

NAFLD related HCC has been recognized as a growing burden in the United States and some European regions. This etiologic scenario is not only changing in high-income countries but also it might be happening in developing ones. In Argentina, even though HCV infection is still the main cause of HCC, recent changing trends in etiology of HCC in Argentina suggests that NAFLD might be the leading HCC cause in the next years, becoming an important Public Health issue.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks to the Latin American Liver Research, Education and Awareness Network (LALREAN).

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Austral University, School of Medicine and the Bioethics Institutional Committee of the Austral University Hospital (CIE approval study protocol number 14-039).

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to the study enrollment. We submit the informed consent (IC) and the Spanish version approved by the Austral University, School of Medicine and the Bioethics Institutional Committee of the Austral University Hospital (CIE approval study protocol number 14-039).

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Invited Manuscript

Peer-review started: November 1, 2017

First decision: December 1, 2017

Article in press: January 15, 2018

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Argentina

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cubero FJ, Qin JM, Zhu X S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li RF

Contributor Information

Federico Piñero, Hepatology and Liver Transplantation Unit, Hospital Universitario Austral, Buenos Aires 1629, Argentina; Sanatorio Trinidad San Isidro, Buenos Aires 1642, Argentina; Clínica Privada San Fernando, Buenos Aires 2013, Argentina.

Josefina Pages, Hepatology and Liver Transplantation Unit, Hospital Universitario Austral, Buenos Aires 1629, Argentina.

Sebastián Marciano, Hepatology Section, Liver Transplant Program, Department of Academic Research, Hospital Italiano from Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires 1424, Argentina.

Nora Fernández, Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Hospital Británico, Buenos Aires 1280, Argentina.

Jorge Silva, Hepatobiliary Surgery, Hospital G Rawson, San Juan 5400, Argentina.

Margarita Anders, Department of Hepatology and Liver Transplant Program, Hospital Aleman, Buenos Aires 1118, Argentina.

Alina Zerega, Department of Hepatology and Liver Transplantation, Sanatorio Allende, Córdoba 5016, Argentina.

Ezequiel Ridruejo, Hepatology Section, Department of Medicine, Centro de Educación Médica e Investigaciones Clínicas Norberto Quirno “CEMIC”, Buenos Aires 1425, Argentina.

Beatriz Ameigeiras, Department of Hepatology, Hospital Ramos Mejía, Buenos Aires 1221, Argentina.

Claudia D’Amico, Department of Hepatology, Centro Especialidades Medicas Ambulatorias (CEMA), Mar del Plata 7600, Argentina.

Luis Gaite, Department of Hepatology and Liver Transplantation, Clínica de Nefrología de Santa Fe, Santa Fe 3000, Argentina.

Carla Bermúdez, Hepatology Section, Liver Transplant Program, Department of Academic Research, Hospital Italiano from Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires 1424, Argentina.

Manuel Cobos, Department of Hepatology and Liver Transplant Program, Hospital Aleman, Buenos Aires 1118, Argentina.

Carlos Rosales, Hepatobiliary Surgery, Hospital G Rawson, San Juan 5400, Argentina.

Gustavo Romero, Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Hospital C Bonorino Udaondo, Buenos Aires 1264, Argentina.

Lucas McCormack, Department of Hepatology and Liver Transplant Program, Hospital Aleman, Buenos Aires 1118, Argentina.

Virginia Reggiardo, Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Hospital Centenario, Santa Fe 2002, Argentina.

Luis Colombato, Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Hospital Británico, Buenos Aires 1280, Argentina.

Adrián Gadano, Hepatology Section, Liver Transplant Program, Department of Academic Research, Hospital Italiano from Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires 1424, Argentina.

Marcelo Silva, Hepatology and Liver Transplantation Unit, Hospital Universitario Austral, Buenos Aires 1629, Argentina.

References

- 1.Alazawi W, Cunningham M, Dearden J, Foster GR. Systematic review: outcome of compensated cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:344–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flemming JA, Kim WR, Brosgart CL, Terrault NA. Reduction in liver transplant wait-listing in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2017;65:804–812. doi: 10.1002/hep.28923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg D, Ditah IC, Saeian K, Lalehzari M, Aronsohn A, Gorospe EC, Charlton M. Changes in the Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection, Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis, and Alcoholic Liver Disease Among Patients With Cirrhosis or Liver Failure on the Waitlist for Liver Transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1090–1099.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piscaglia F, Svegliati-Baroni G, Barchetti A, Pecorelli A, Marinelli S, Tiribelli C, Bellentani S; HCC-NAFLD Italian Study Group. Clinical patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A multicenter prospective study. Hepatology. 2016;63:827–838. doi: 10.1002/hep.28368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fassio E, Díaz S, Santa C, Reig ME, Martínez Artola Y, Alves de Mattos A, Míguez C, Galizzi J, Zapata R, Ridruejo E, de Souza FC, Hernández N, Pinchuk L; Multicenter Group for Study of Hepatocarcinoma in Latin America; Asociación Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Hígado (ALEH) Etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Latin America: a prospective, multicenter, international study. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9:63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fassio E, Míguez C, Soria S, Palazzo F, Gadano A, Adrover R, Landeira G, Fernández N, García D, Barbero R, et al. Etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Argentina: results of a multicenter retrospective study. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2009;39:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debes JD, Chan AJ, Balderramo D, Kikuchi L, Gonzalez Ballerga E, Prieto JE, Tapias M, Idrovo V, Davalos MB, Cairo F, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in South America: Evaluation of risk factors, demographics and therapy. Liver Int. 2018;38:136–143. doi: 10.1111/liv.13502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piñero F, Tisi Baña M, de Ataide EC, Hoyos Duque S, Marciano S, Varón A, Anders M, Zerega A, Menéndez J, Zapata R, Muñoz L, Padilla Machaca M, Soza A, McCormack L, Poniachik J, Podestá LG, Gadano A, Boin IS, Duvoux C, Silva M; Latin American Liver Research, Education and Awareness Network (LALREAN) Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: evaluation of the alpha-fetoprotein model in a multicenter cohort from Latin America. Liver Int. 2016;36:1657–1667. doi: 10.1111/liv.13159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabrielli M, Vivanco M, Hepp J, Martínez J, Pérez R, Guerra J, Arrese M, Figueroa E, Soza A, Yáñes R, et al. Liver transplantation results for hepatocellular carcinoma in Chile. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa PE, Vasconcelos JB, Coelho GR, Barros MA, Neto BA, Pinto DS, Júnior JT, Correia FG, Garcia JH. Ten-year experience with liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in a Federal University Hospital in the Northeast of Brazil. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:1794–1798. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvalaggio PR, Caicedo JC, de Albuquerque LC, Contreras A, Garcia VD, Felga GE, Maurette RJ, Medina-Pestana JO, Niño-Murcia A, Pacheco-Moreira LF, et al. Liver transplantation in Latin America: the state-of-the-art and future trends. Transplantation. 2014;98:241–246. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piñero F, Marciano S, Anders M, Orozco F, Zerega A, Cabrera CR, Baña MT, Gil O, Andriani O, de Santibañes E, et al. Screening for liver cancer during transplant waiting list: a multicenter study from South America. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:355–360. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piñero F, Marciano S, Anders M, Orozco Ganem F, Zerega A, Cagliani J, Andriani O, de Santibañes E, Gil O, Podestá LG, et al. Identifying patients at higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation in a multicenter cohort study from Argentina. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:421–427. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidence-Based Diagnosis, Staging, and Treatment of Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:835–853. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duvoux C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Decaens T, Pessione F, Badran H, Piardi T, Francoz C, Compagnon P, Vanlemmens C, Dumortier J, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a model including α-fetoprotein improves the performance of Milan criteria. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:986–994.e3; quiz e14-15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrilho FJ, Kikuchi L, Branco F, Goncalves CS, Mattos AA; Brazilian HCC Study Group. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of hepatocellular carcinoma in Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010;65:1285–1290. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010001200010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ascha MS, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Feldstein AF, Zein NN. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1972–1978. doi: 10.1002/hep.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan MM, Hwang LY, Hatten CJ, Swaim M, Li D, Abbruzzese JL, Beasley P, Patt YZ. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: synergism of alcohol with viral hepatitis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology. 2002;36:1206–1213. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong RJ, Cheung R, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology. 2014;59:2188–2195. doi: 10.1002/hep.26986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siriwardana RC, Niriella MA, Dassanayake AS, Liyanage C, Gunathilaka B, Jayathunge S, de Silva HJ. Clinical characteristics and outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma in alcohol related and cryptogenic cirrhosis: a prospective study. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2015;14:401–405. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(15)60343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perumpail RB, Wong RJ, Ahmed A, Harrison SA. Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Setting of Non-cirrhotic Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and the Metabolic Syndrome: US Experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:3142–3148. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3821-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]