Abstract

AIM

To analyse the effect of mechanical bowel preparation vs no mechanical bowel preparation on outcome in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery.

METHODS

Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies comparing adult patients receiving mechanical bowel preparation with those receiving no mechanical bowel preparation, subdivided into those receiving a single rectal enema and those who received no preparation at all prior to elective colorectal surgery.

RESULTS

A total of 36 studies (23 randomised controlled trials and 13 observational studies) including 21568 patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery were included. When all studies were considered, mechanical bowel preparation was not associated with any significant difference in anastomotic leak rates (OR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.74 to 1.10, P = 0.32), surgical site infection (OR = 0.99, 95%CI: 0.80 to 1.24, P = 0.96), intra-abdominal collection (OR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.63 to 1.17, P = 0.34), mortality (OR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.57 to 1.27, P = 0.43), reoperation (OR = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.75 to 1.12, P = 0.38) or hospital length of stay (overall mean difference 0.11 d, 95%CI: -0.51 to 0.73, P = 0.72), when compared with no mechanical bowel preparation, nor when evidence from just randomized controlled trials was analysed. A sub-analysis of mechanical bowel preparation vs absolutely no preparation or a single rectal enema similarly revealed no differences in clinical outcome measures.

CONCLUSION

In the most comprehensive meta-analysis of mechanical bowel preparation in elective colorectal surgery to date, this study has suggested that the use of mechanical bowel preparation does not affect the incidence of postoperative complications when compared with no preparation. Hence, mechanical bowel preparation should not be administered routinely prior to elective colorectal surgery.

Keywords: Bowel preparation, Mechanical, Antibiotics, Morbidity, Mortality, Surgery, Outcome complications, Meta-analysis

Core tip: At present there is no evidence that bowel preparation makes a difference to clinical outcomes in either colonic or rectal surgery, in terms of anastomotic leak rates, surgical site infection, intra-abdominal collection, mortality, reoperation or hospital length of stay. Given its potential adverse effects and patient dissatisfaction rates, it should not be administered routinely to patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) for colorectal surgery has been surgical dogma for decades, despite increasing evidence from the 1990s refuting its benefits[1,2]. The rationale behind the administration of MBP is that it reduces fecal bulk and, therefore, bacterial colonisation, thereby reducing the risk of postoperative complications such as anastomotic leakage and wound infection[3], as well as to facilitate dissection and allow endoscopic evaluation. Opponents argue that in the 21st century, with rational use of oral and intravenous prophylactic antibiotics there is no longer a place for MBP, that it may cause marked fluid and electrolyte imbalance in the preoperative period, and that evidence has shown that the gut microbial flora load is not reduced grossly by bowel preparation[4]. There is also concern that bowel preparation liquefies feces, thereby increasing the risk of spillage and contamination intra-operatively[5]. Its use remains controversial, particularly within the context of an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program setting[6,7].

Meta-analyses[8-12] have been published on MBP in elective colorectal surgery showing mixed results, with most studies demonstrating no difference in infective complications between patients receiving MBP or control treatment, although control treatment varied significantly between the use of a rectal enema or absolutely no preparation. Similar results have been found in gynaecological[13,14] and urological[15,16] surgery where studies have shown no benefits in visualisation, bowel handling or complication rates between patients treated with bowel preparation and those given no bowel preparation. As a result of this inconclusive evidence, several studies have established that practice varies significantly between countries, and even surgeons in the same institution[17,18]. Further impediments to the issue are that no consensus has yet been reached regarding the optimal method of bowel cleansing. Various agents such as polyethylene glycol (PEG), sodium phosphate, mannitol, milk of magnesia, liquid paraffin and senna have been used to achieve bowel cleansing.

Infective complications are amongst the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in patients undergoing colorectal surgery[19]. However, MBP is not without its own complications and the process is both time-consuming and unpleasant for patients[20]. It has been shown to cause clinically significant dehydration[21] and electrolyte disturbances, particularly hypocalcaemia and hypokalaemia to which the elderly are especially vulnerable[22-24]. Patient satisfaction is poor for undergoing bowel preparation prior to surgery and colonoscopy, and this may necessitate an additional day preoperatively in hospital, particularly for frail elderly patients.

In the United Kingdom, the National Institution of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) does not recommend using MBP routinely to reduce the risk of surgical site infection (SSI)[25] and the ERAS® Society guidelines on perioperative care of patients undergoing colonic resection[6] also recommend against using preoperative bowel preparation. However, for rectal[7] resection the recommendation, albeit weak, is to use MBP for patients undergoing anterior resection with diverting stomas. In recent years further evidence has emerged from large database studies using the National Surgical Quality Improvement (NSQIP) database in America[26-29] showing reduced rates of anastomotic leakage, intra-abdominal abscess formation and wound infection when patients were given MBP with intraluminal antibiotics pre-operatively.

We have assessed this expanding body of evidence in this new comprehensive meta-analysis encompassing both randomised controlled trials and observational studies. We sought to address deficiencies in previous studies by including all levels of evidence, separating those in which patients received a single rectal enema vs full or no preparation, and including the recently published large database studies.

Our aims for this meta-analysis were: (1) To analyse the effect of MBP vs no preparation or rectal enema alone on postoperative infective complications in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery; (2) To examine the differences in results between evidence obtained from randomised controlled trials and observational studies; and (3) To determine what effect, if any, bowel preparation had on postoperative complications in rectal surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search Strategy

We performed an electronic search of the PubMed database and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify studies comparing outcomes in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery treated with MBP vs either no preparation or a single rectal enema (last search on 1st May 2017). We used the search terms “(bowel preparation OR bowel cleansing OR bowel cleaning) AND (surgery OR preoperative)”. Further sources were obtained by a manual search of the bibliography of the papers obtained to ensure the search was as comprehensive as possible. We did not apply language restriction or time limitations. Two independent researchers (KER and HJ-E) reviewed the abstracts for inclusion. Where there was a difference of opinion on the inclusion of papers, the opinion of the senior author was sought (DNL). We performed this meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)[30] and Guidelines for Meta-Analyses and Systematic Review of Observational Studies (MOOSE) statements[31].

Selection of articles

We reviewed full text articles for suitability after excluding studies on the basis of title and abstract. Our inclusion criteria specified that studies must have a minimum of two comparator groups and were either designed as randomised controlled trials or observational studies. Publications comparing preoperative MBP with no preparation or a single rectal enema were included and comparisons with other forms of bowel preparation (e.g. intraoperative colonic lavage) were excluded. Only studies on adult patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery were included. We included studies on laparoscopic and open surgical procedures but excluded endoscopic studies. Relevant outcome measures were anastomotic leak, SSI, intra-abdominal abscess, mortality, reoperation and hospital length of stay.

Duplication of results was a particular hazard encountered when selecting which of the studies to include that extracted information from the NSQIP database[26-29,32-36]. The papers were scrutinised for their enrollment dates. There was overlap in these dates and after correspondence with the authors, it was apparent that there was considerable overlap in the data sets used. Hence, we selected the largest study for inclusion with the greatest number of clinically relevant outcome measures[29]. Two further studies[37,38] had duplication of results and in this situation the larger of the two studies was included[38]. One study[39] was a subgroup analysis of patients undergoing anastomosis below the peritoneal reflection taken from a study which was already included[40] in the meta-analysis so this was excluded from the main meta-analysis to prevent dual inclusion of patients. However, this subgroup was included in the separate analysis of rectal surgery. A further study[41] reviewed as a full text article was retracted since its inclusion in the 2011 Cochrane Review[10], so we chose to exclude this. One paper[2] analysed in the Cochrane Review included pediatric patients and so has been excluded from our meta-analysis.

Data extraction

HJ-E extracted the data and they were verified independently by KER. Quantitative data relevant to the endpoints we selected were extracted. Several studies presented hospital length of stay results in formats other than mean and standard deviation. Where this occurred, the authors were contacted for the raw data in order to ascertain the mean and standard deviation necessary for creation of Forest plot. When the raw data were unavailable, mean and standard deviation were calculated using the technique described by Hozo et al[42].

Risk of bias and completeness of reporting of individual studies

The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool in RevMan 5.3[43], which focuses upon random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and selective reporting (reporting bias).

Statistical analysis

The analysis was performed using RevMan 5.3 software[43]. Continuous variables were calculated as a mean difference and 95% confidence interval using an inverse variance random effects model. Dichotomous variables were analysed using the Mantel-Haenszel random effects model to quote the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval. These analyses were used to construct forest plots, with statistical significance taken to be a P value of < 0.05 on two tailed testing. A predetermined subgroup analysis was performed for the impact of MBP in rectal surgery specifically using the same methodology. Study inconsistency and heterogeneity were assessed using the I2 statistic[44].

Protocol registration

The protocol for this meta-analysis was registered with the PROSPERO database (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero) - registration number CRD42015025279.

RESULTS

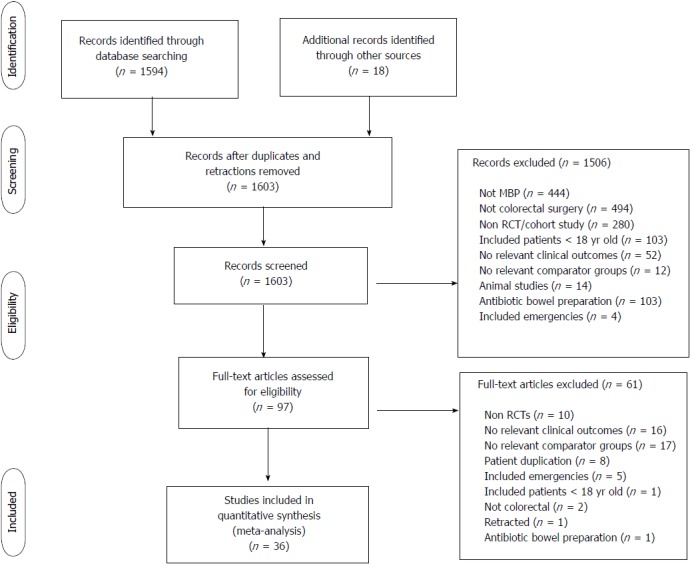

From 1594 studies identified from the original search, 97 were reviewed as full text articles. Of these, 36 comprising 23[37,40,45-65] randomised controlled trials and 13 observational studies[29,66-77] were eligible for inclusion (Figure 1). The risk of bias of the randomised controlled trials included in this study was moderate (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram showing identification of relevant studies from initial search, PRISMA: Preferred reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Table 1.

Risk of bias of studies included

| Ref. | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting |

| Ji et al[76] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chan et al[77] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hu et al[64] | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Bhattacharjee et al[65] | + | ? | - | ? | ? | ? |

| Allaix et al[74] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kiran et al[29] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Yamada et al[66] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Otchy et al[67] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kim et al[75] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tahirkheli et al[62] | + | ? | ? | ? | - | - |

| Sasaki et al[61] | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Bertani et al[45] | + | + | ? | ? | + | + |

| Roig et al[68] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bretagnol et al[46] | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Pitot et al[69] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Alcantara Moral et al[47] | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Miron et al[70] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pena-Soria et al[48] | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Leiro et al[59] | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Contant et al[40] | + | + | - (2) | - (2) | - | + |

| Bretagnol et al[71] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Jung et al[49] | + | + | + | + | - | ? |

| Veenhof et al[72] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ali et al[63] | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Jung et al[50] | + | + | + | + | - | ? |

| Platell et al[51] | + | + | + | + | - | - |

| Fa-Si-Oen et al[52] | + | + | ? | ? | + | + |

| Bucher et al[53] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ram et al[54] | + | - (1) | ? | ? | ? | + |

| Zmora et al[37] | + | + | ? | ? | - | + |

| Young Tabusso et al[55] | ? | ? | - (2) | - (2) | ? | ? |

| Miettinen et al[56] | + | + | ? | ? | + | + |

| Memon et al[73] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Fillmann et al[60] | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Burke et al[57] | ? | ? | + | + | - | - |

| Brownson et al[58] | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

NA: Not applicable (observational study); +: Low risk of bias; -: High risk of bias; (1): Allocation concealment utilized identification number of patient (odd or even); (2): Not blinded.

Patient demographics

Overall, 21568 patients were included in the meta-analysis, of whom 6166 had no bowel preparation of any sort, 2739 had a solitary rectal enema and 12663 underwent full MBP as per local policy. Of these, 6277 patients were included in randomised controlled trials and 15291 in observational studies. Demographic details are summarised in Table 2 and of details of interventions (bowel preparation and perioperative antibiotics) in Table 3.

Table 2.

Baseline patient demographics for all studies included

| Ref. | Year published | Study methodology | Study numbers | Male: Female gender | Indication for surgery | Location | Primary anastomosis | Laparoscopic approach | |||

| MBP, n | No MBP, n | MBP | No MBP | MBP, n | No MBP, n | ||||||

| Ji et al[76] | 2017 | Observational | 538 | 831 | Unknown | Unknown | Cancer | Rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Chan et al[77] | 2016 | Observational | 159 | 97 | 85:74 | 55:42 | Cancer | Colon and rectum | Y | 159 | 97 |

| Hu et al[64] | 2017 | RCT | 76 | 72 | Unknown | Unknown | Cancer | Colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Bhattacharjee et al[65] | 2015 | RCT | 38 | 33 | 21:17 | 20:13 | Cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, volvulus, tuberculosis | Colon and rectum | Y | 0 | 0 |

| Allaix et al[74] | 2015 | Observational | 706 | 829 | 361:345 | 432:397 | Cancer, adenoma, diverticulitis, reversal of Hartmann’s procedure, rectal prolapse | Colon and rectum | Y | 829 | 706 |

| Kiran et al[29] | 2015 | Observational | 6146 | 2296 | 3030:3116 | 1111:1185 | Unknown | Colon and rectum | N | 4443 | 1389 |

| Yamada et al[66] | 2014 | Observational | 152 | 106 | 92:60 | 65:41 | Cancer | Colon only | Y | 97 | 64 |

| Otchy et al[67] | 2014 | Observational | 86 | 79 | 39:47 | 39:40 | Cancer, diverticular disease, IBD, rectal prolapse, ischemic colitis, volvulus, colovaginal fistula | Colon and rectum | Y | 37 | 48 |

| Kim et al[75] | 2014 | Observational | 1363 | 1112 | 502:694 | 669:610 | Unknown | Colon and rectum | Y | 709 | 472 |

| Tahirkheli et al[62] | 2013 | RCT | 48 | 48 | 28:20 | 24:24 | Cancer, diverticular disease, IBD, ischemic colitis | Colon and rectum | Y | unknown | unknown |

| Sasaki et al[61] | 2012 | RCT | 38 | 41 | 17:21 | 24:17 | Cancer | Colon only | Y | 29 | 19 |

| Bertani et al[45] | 2011 | RCT | 114 | 115 | 65:49 | 60:55 | Cancer | Colon and rectum | Y | 55 | 51 |

| Roig et al[68] | 2010 | Observational | 39 | 69 | Unknown | Unknown | Cancer, diverticular disease, IBD, FAP | Colon and rectum | Y | 12 | 20 |

| Bretagnol et al[46] | 2010 | RCT | 89 | 89 | 56:33 | 46:43 | Rectal cancer | Rectum only | Y | 73 | 74 |

| Pitot et al[69] | 2009 | Observational | 59 | 127 | 31:28 | 53:74 | Cancer, diverticular disease, IBD | Colon only | Y | 26 | 30 |

| Alcantara Moral et al[47] | 2009 | RCT | 70 | 69 | 41:28 | 48:22 | Cancer | Left colon and rectum | Y | 12 | 15 |

| Miron et al[70] | 2008 | Observational | 60 | 39 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Pena-Soria et al[48] | 2008 | RCT | 65 | 64 | 35:29:00 | 33:22 | Cancer, IBD | Colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Leiro et al[59] | 2008 | RCT | 64 | 65 | 39:25 | 38:27 | Benign and malignant colorectal pathology | Colon and rectum | N | Unknown | Unknown |

| Contant et al[40] | 2007 | RCT | 670 | 684 | 337:333 | 345:339 | Cancer, IBD | Colon and rectum | Y | None | None |

| Bretagnol et al[71] | 2007 | Observational | 61 | 52 | 42:19 | 32:20 | Rectal cancer | Rectum only | Y | Unknown | 27 |

| Jung et al[49] | 2007 | RCT | 686 | 657 | 306:380 | 317:340 | Cancers, diverticular disease, adenoma | Colon only | Y | None | None |

| Veenhof et al[72] | 2007 | Observational | 78 | 71 | 28:43 | 33:45 | Not specified | Colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Ali et al[63] | 2007 | RCT | 109 | 101 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Jung et al[50] | 2006 | RCT | 27 | 17 | Unknown | Unknown | Cancer, adenoma and diverticular disease | Rectum only | Y | None | None |

| Platell et al[51] | 2006 | RCT | 147 | 147 | Unknown | Unknown | Cancer, IBD, diverticular disease, adenoma | Colon and rectum | N | Unknown | Unknown |

| Fa-Si-Oen et al[52] | 2005 | RCT | 125 | 125 | 58:67 | 56:69 | Cancer, diverticular disease | Colon only | Y | None | None |

| Bucher et al[53] | 2005 | RCT | 78 | 75 | 47:31 | 34:41 | Cancer, diverticular disease, reversal of Hartmann’s procedure, adenoma, endometriosis | Left colon and rectum | Y | 20 | 22 |

| Ram et al[54] | 2005 | RCT | 164 | 165 | 99:65 | 102:63 | Cancer, diverticular disease, IBD | Colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Zmora et al[37] | 2003 | RCT | 187 | 193 | 103:84 | 94:99 | Cancer, diverticular disease, IBD | Colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Young Tabusso et al[55] | 2002 | RCT | 24 | 23 | 12:12 | 9:14 | Unknown | Colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Miettinen et al[56] | 2000 | RCT | 138 | 129 | 68:70 | 62:67 | Cancer, IBD, diverticular disease | Colon and rectum | 91% primary anastomosis in both arms | None | None |

| Memon et al[73] | 1997 | Observational | 61 | 75 | 32:29 | 44:31 | Cancer, diverticular disease, IBD, adenoma, lipoma | Left colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Fillmann et al[60] | 1995 | RCT | 30 | 30 | Unknown | Unknown | Cancer, diverticular disease, IBD, ischemic colitis | Colon and rectum | N | Unknown | Unknown |

| Burke et al[57] | 1994 | RCT | 82 | 87 | 52:30 | 43:44 | Cancer, diverticular disease, IBD | Left colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

| Brownson et al[58] | 1992 | RCT | 86 | 93 | Unknown | Unknown | Cancer and other | Colon and rectum | Y | Unknown | Unknown |

FAP: Familial adenomatous polyposis; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; MBP: Mechanical bowel preparation; RCT: Randomised controlled trial.

Table 3.

Nature of the bowel preparation used in studies included in the meta-analysis

| Ref. | Details of MBP | Details of no MBP | Antibiotics given |

| Allaix et al[74] | PEG | Enema before left sided operations | As per local policy |

| Kiran et al[29] | As per local policy | Unclear | As per local policy |

| Yamada et al[66] | PEG | Glycerin Enema | Flomoxef at induction and 3 hourly intra op |

| Otchy et al[67] | PEG | Colonic resections- no MBP | Ertapenem 1 g or levofloxacin/metronidazole 500 mg 1 h post op then continued for 24 h post op |

| Rectal resections- single enema | |||

| Kim et al[75] | As per local policy | Unclear | As per local policy |

| Tahirkheli et al[62] | Saline | No preparation | Oral ciprofloxacin plus unspecified intravenous antibiotics for 24 h post op |

| Sasaki et al[61] | PEG and sodium picosulphate | No preparation | Antibiotic regime not specified |

| Bertani et al[45] | PEG and a single enema | Single enema only | Cefotixin given at induction, 4, 12 and 24 h. Ceftriaxone and metronidazole given for 5 d post op if heavy contamination |

| Roig et al[68] | Mono and di sodium phosphate | No prep | Antibiotic regime not specified |

| Bretagnol et al[46] | Senna plus povidone-iodine enema | No prep | ceftriaxone and metronidazole at induction and every 2 hours intra op |

| Pitot et al[69] | PEG | Rectal resections had single enema | Antibiotic regime not specified |

| Alcantara Moral et al[47] | Sodium phosphate or PEG | Two preoperative enemas | Neomycin and metronidazole 1 d pre op, ceftriaxone and metronidazole at induction |

| Miron et al[70] | PEG and sodium sulphate | No preparation | Antibiotic regime not specified |

| Pena-Soria et al[48] | PEG and standard enema | No preparation | Gentamicin and metronidazole 30 min pre op and 8 hourly post op |

| Leiro et al[59] | Sodium di or monobasic phosphate or PEG | No preparation | Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole 500 mg pre op |

| Contant et al[40] | PEG and bisocodyl/ sodium phosphate | No preparation | Antibiotic regime not specified |

| Bretagnol et al[71] | Senna plus povidone-iodine enema | No preparation | Ceftriaxone and metronidazole at induction and every 2 h intra op |

| Jung et al[49] | As per local policy | No preparation | Trimethoprim + metronidazole or cef and met or dozy and met |

| Veenhof et al[72] | PEG | Single enema | Antibiotic regime not specified |

| Ali et al[63] | Saline | No preparation | Antibiotic regime not specified |

| Jung et al[50] | PEG or sodium phosphate | No preparation | Oral sulphamethoxazole-trimethoprim and metronidazole, cephalsporin and metronidazole, doxycycline and metronidazole |

| Platell et al[51] | PEG | Phosphate enema | Timentin or gentamycin and metronidazole at induction |

| Fa-Si-Oen et al[52] | PEG | No preparation | Ceftriaxone and metronidazole or gentamycin and metronidazole at induction |

| Bucher et al[53] | PEG | Rectal resections had single saline enema | Ceftriaxone and metronidazole at induction and 24 h post op |

| Ram et al[54] | Monobasic and dibasic sodium phosphate | No preparation | Ceftriaxone and metronidazole 1 h pre op and 48 post op |

| Zmora et al[37] | PEG | Rectal resections had a single phosphate enema | Erythromycin and neomycin for 3 doses and then for 24 h |

| Young Tabusso et al[55] | PEG or saline/mannitol | No preparation | Antibiotic regime not specified |

| Miettinen et al[56] | PEG | No preparation | Ceftriaxone and metronidazole at induction |

| Memon et al[73] | Phosphate enema, picolax, PEG, saline lavage | No preparation | Antibiotic regime not specified |

| Fillmann et al[60] | Mannitol | No preparation | Metronidazole and gentamicin 1 h pre op then for 48 h |

| Burke et al[57] | sodium picosulphate | No preparation | Ceftriaxone 1 g, metronidazole at induction and 8 and 16 h |

| Brownson et al[58] | PEG | No preparation | Antibiotic regime not specified |

MBP: Mechanical bowel preparation; PEG: Polyethylene glycol.

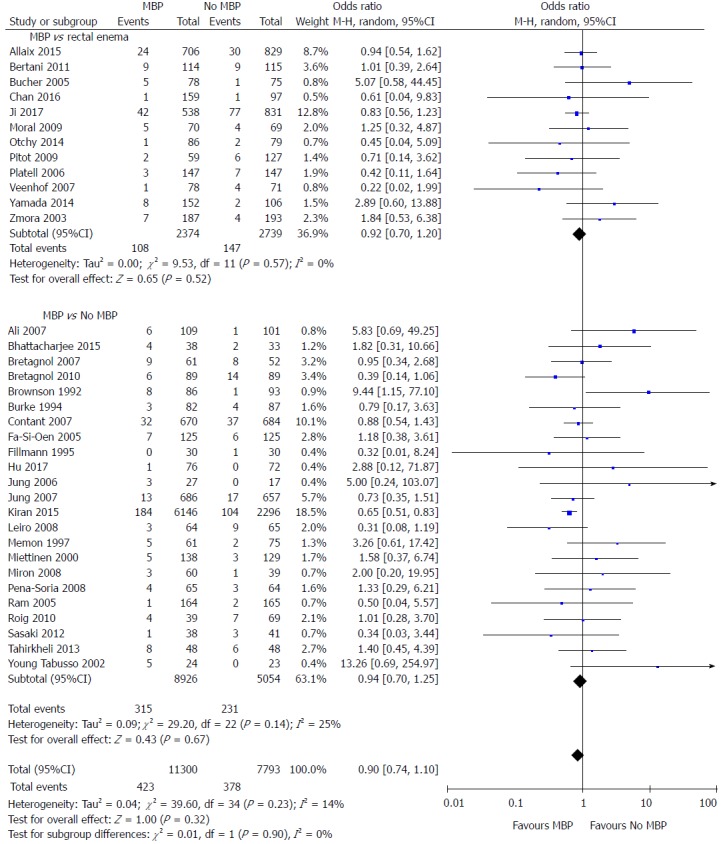

Anastomotic leak

All studies except one[75] included data on the primary outcome measure of this meta-analysis, the incidence of anastomotic leak (Figure 2). When MBP was compared with no MBP (including no preparation at all and those who underwent a single rectal enema), there was no difference in the incidence of anastomotic leak (OR = 0.90, 95%CI: 0.74 to 1.10, P = 0.32). When MBP vs absolutely no MBP was analysed[29,40,46,48-50,52,54-65,68,70,71,73], this made no difference to anastomotic leak rates (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.25, P = 0.67), nor when MBP was compared with a single rectal enema[37,45,47,51,53,66,67,69,72,74,76,77] (OR = 0.92, 95%CI: 0.70 to 1.20, P = 0.52).

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing overall anastomotic leak rate for patients receiving mechanical bowel preparation vs either a single rectal enema (top) or absolutely no preparation (bottom). A Mantel-Haenszel random effects model was used to perform the meta-analysis and odds ratios are quoted including 95% confidence intervals. MBP: Mechanical bowel preparation.

When randomised controlled trials alone were included in the analysis[37,40,45-65] (Supplementary figure 1A), the use of MBP vs no MBP did not affect the incidence of anastomotic leak (OR = 1.02, 95%CI: 0.75 to 1.40, P = 0.90), nor when MBP vs absolutely no MBP[40,46,48-50,52,54-65] or MBP vs single rectal enema[37,45,47,51,53]were considered. When observational studies alone were analysed[66-73,76,77] (Supplementary figure 1B), the use of MBP vs no MBP did significantly affect the incidence of anastomotic leak (OR = 0.76, 95%CI: 0.63 to 0.91, P = 0.003), although this was not significant when MBP vs single rectal enema[66,67,69,72,74,76,77] and MBP vs absolutely no MBP[29,68,70,71,73] were considered separately.

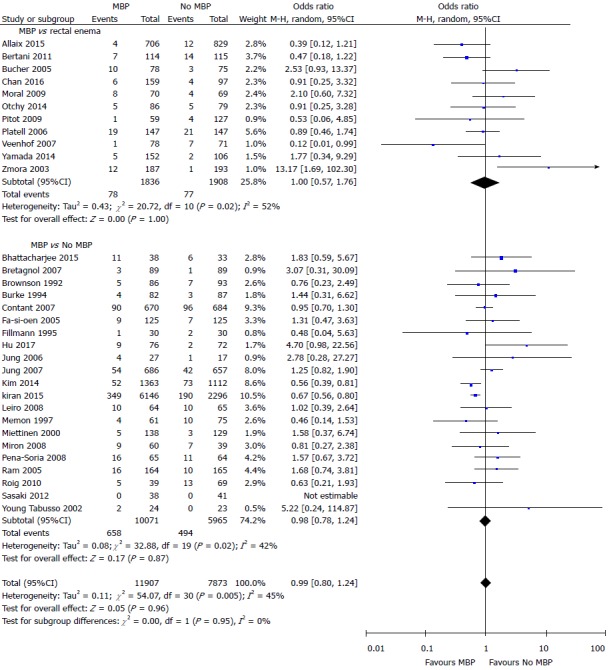

SSI

Data on the incidence of SSI were presented in a total of 19780 patients in 32 studies[29,37,40,45-61,64-70,72-75,77] (Figure 3). There was no difference in the incidence of SSI in those who did vs those who did not undergo MBP (OR = 0.99, 95%CI: 0.80 to 1.24, P = 0.96), nor in those who had MBP vs those receiving a single rectal enema[37,45,47,51,53,66,67,69,72,74,77] (OR = 1.00, 95%CI: 0.57 to 1.76, P = 1.00) or those who had MBP vs those receiving absolutely no preparation[29,40,46,48-50,52,54-61,64,65,68,70,73,75] (OR = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.78 to 1.24, P = 0.87).

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing overall surgical site infection rates for patients receiving mechanical bowel preparation vs either a single rectal enema (top) or absolutely no preparation (bottom). A Mantel-Haenszel random effects model was used to perform the meta-analysis and odds ratios are quoted including 95% confidence intervals. MBP: Mechanical bowel preparation.

When data obtained from 21 randomised controlled trials[37,40,43,45-61,64,65] alone with a total of 5971 patients were included (Supplementary figure 2A), the use of MBP vs no MBP did not impact upon the incidence of SSI (OR = 1.16, 95%CI: 0.96 to 1.39, P = 0.12), nor when MBP vs single rectal enema[37,45,47,51,53] or MBP vs absolutely no preparation[40,43,46,48-50,52,54-61,64,65] were considered. When just observational studies were included[29,66-70,72-75,77] (11 studies, 13809 patients; Supplementary figure 2B), patients who received MBP had a significantly reduced incidence of SSI than those who did not receive MBP (OR = 0.64, 95%CI: 0.55 to 0.75, P < 0.0001), with similar results seen in those who received MBP vs absolutely no MBP[29,68,70,73,75], although no difference was seen between those who received full MBP vs a single rectal enema[66,67,69,72,74,77].

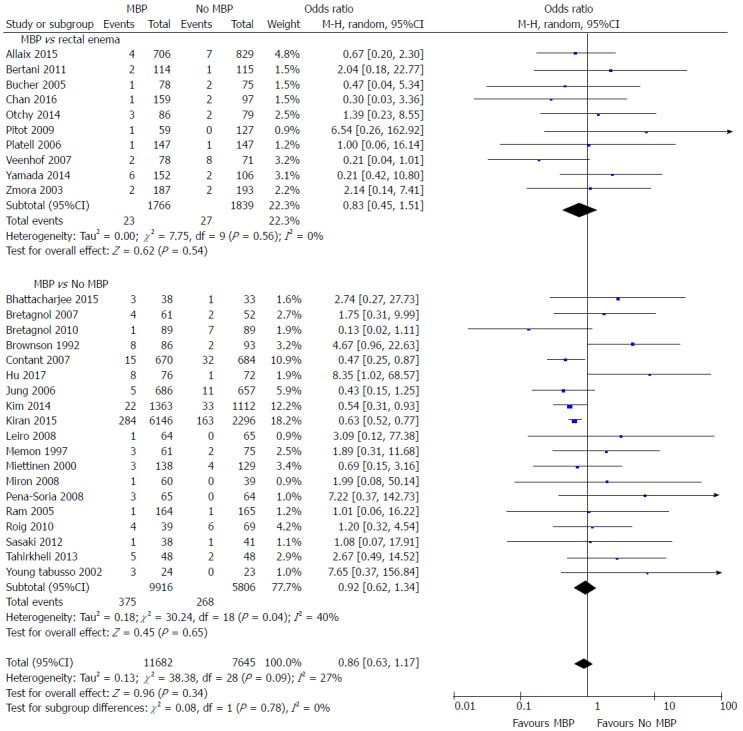

Intra-abdominal collection

A total of 29 studies[29,37,40,45,46,48,49,51,53-56,58,59,61,62,64-75,77] on 19327 patients included data on postoperative intra-abdominal collections (Figure 4). The administration of MBP vs no MBP did not impact upon the incidence of intra-abdominal collection (OR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.63 to 1.17, P = 0.34), nor when full MBP vs single rectal enema[37,45,47,51,53,66,67,69,72,74,77] (OR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.45 to 1.51, P = 0.54) or MBP vs absolutely no preparation at all were considered[29,40,46,48-50,52,54-61,64,65,68,70,73,75] (OR = 0.92, 95%CI: 0.62 to 1.34, P = 0.65).

Figure 4.

Forest plot comparing overall intra-abdominal collection rates for patients receiving mechanical bowel preparation vs either a single rectal enema (top) or absolutely no preparation (bottom). A Mantel-Haenszel random effects model was used to perform the meta-analysis and odds ratios are quoted including 95% confidence intervals. MBP: Mechanical bowel preparation.

When randomised controlled trials alone were considered[37,40,45,46,48,49,51,53-56,58,59,61,62,64,65] (Supplementary figure 3A), no differences were seen in the incidence of intra-abdominal collection between any of the groups (OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 0.66 to 2.10, P = 0.59). However, when observational studies were analysed[29,66-75,77] (Supplementary figure 3B), the incidence of intra-abdominal collection was significantly reduced in those who had MBP vs those who did not (OR = 0.67, 95%CI: 0.53 to 0.85, P = 0.0008). A significant reduction in the incidence of intra-abdominal collection was seen in the subgroup of patients who underwent MBP vs absolutely no preparation[29,68,70,71,73,75] (OR = 0.65, 95%CI: 0.54 to 0.78, P < 0.0001), however no difference was seen in those undergoing MBP vs a single rectal enema[66,67,69,72,74,77] (OR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.34 to 1.88, P = 0.60).

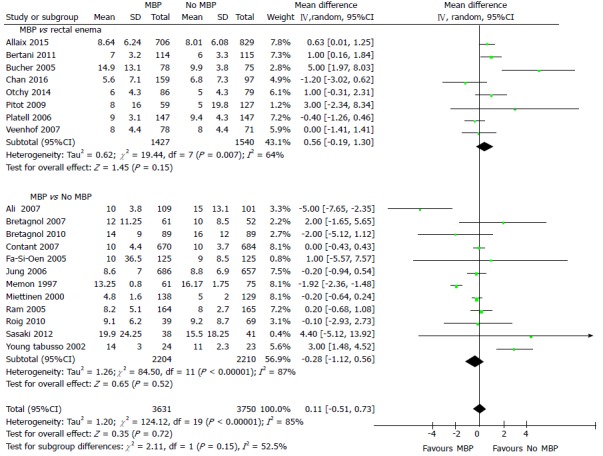

Hospital length of stay

Hospital length of stay (LOS) was reported in 20 studies[40,45,46,49,51-56,61,63,67-69,71-74,77] including 7381 patients (Figure 5), with the use of MBP vs not (including those who received a single rectal enema) resulting in no significant difference in hospital length of stay (overall mean difference 0.11 d, 95%CI: -0.51 to 0.73, P = 0.72). This was mirrored when just randomised controlled trials were examined[40,45,46,49,51-56,61,63] (Supplementary figure 4A; overall mean difference 0.22 d, 95%CI: -0.44 to 0.88, P = 0.52) and when just observational studies were included[67-69,71-74,77] (Supplementary figure 4B; overall mean difference -0.12 d, 95%CI: -1.48 to 1.25, P = 0.87).

Figure 5.

Forest plot comparing overall hospital length of stay for patients receiving mechanical bowel preparation vs either a single rectal enema (top) or absolutely no preparation (bottom). An inverse-variance random effects model was used to perform the meta-analysis and mean differences are quoted including 95% confidence intervals. MBP: Mechanical bowel preparation.

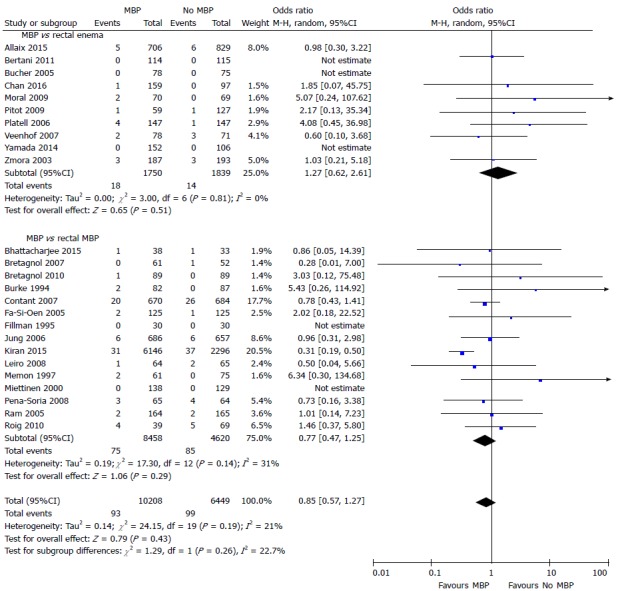

Mortality

Mortality was reported in 25 studies[29,37,40,45-49,51-54,56,57,59,60,65,66,68,69,71-74,77] that included 16657 patients (Figure 6). The time point this outcome measure was measured was variable between studies, with the majority taken at 30 d[29,37,45-49,51,53,60,65,69,71,73,77], two taken at first outpatient clinic quoted to be approximately two weeks following hospital discharge[40] or four weeks following surgery[66], one at two months[56] and one at three months[52], with six papers not stating when mortality was taken from[54,57,59,68,72,74]. No difference was seen with the use of full MBP, single rectal enema or no preparation at all.

Figure 6.

Forest plot comparing overall mortality rates for patients receiving mechanical bowel preparation vs either a single rectal enema (top) or absolutely no preparation (bottom). A Mantel-Haenszel random effects model was used to perform the meta-analysis and odds ratios are quoted including 95% confidence intervals. MBP: Mechanical bowel preparation.

A similar result was seen, with no significant differences, when this comparison was made using only randomised controlled trials[37,40,45-49,51-54,56,57,59,60,65] (Supplementary figure 5A). However, in observational studies[29,66,68,69,71-74,77], MBP was associated with a significant reduction in mortality (OR = 0.50, 95%CI: 0.34 to 0.74, P = 0.0005) (Supplementary figure 5B). A significant reduction in the incidence of intra-abdominal collection was seen in the subgroup of patients in observational studies who underwent MBP vs absolutely no preparation[29,68,71,73] (OR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.27 to 0.56, P < 0.0001). However, no difference was seen in those undergoing MBP vs a single rectal enema[66,69,72,74,77] (OR = 0.99, 95%CI: 0.41 to 2.41, P = 0.98).

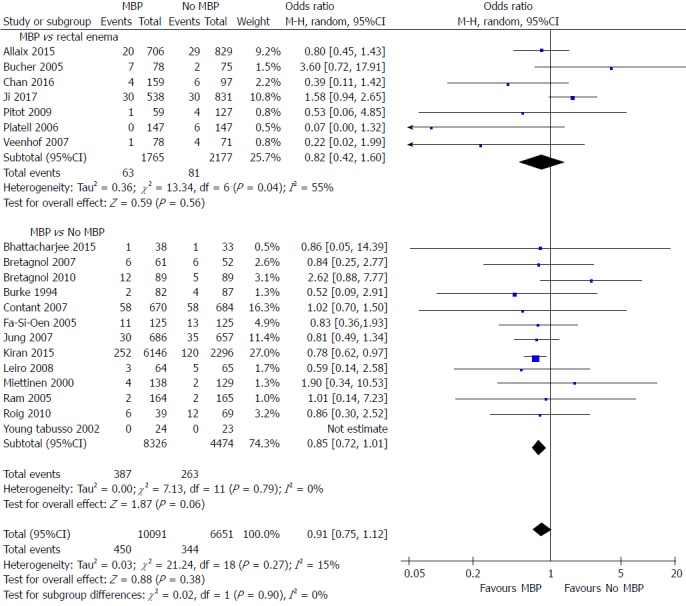

Reoperation

A total of 20 studies on 16742 patients[29,40,46,49,51-57,59,65,68,69,71,72,74,76,77] examined the impact of MBP upon reoperation rates (Figure 7). Overall the use of MBP vs no MBP did not impact upon requirement for reoperation[29,40,46,49,51-57,59,65,68,69,71,72,74,76,77] (OR = 0.91, 95%CI: 0.75 to 1.12, P = 0.38), nor when MBP vs a single rectal enema[51,53,69,72,74,76,77] (OR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.42 to 1.60, P = 0.56) or MBP vs absolutely no preparation[29,40,46,49,52,54-57,59,65,68,71] (OR = 0.85, 95%CI: 0.72 to 1.01, P = 0.06) were compared.

Figure 7.

Forest plot comparing overall reoperation rates for patients receiving mechanical bowel preparation vs either a single rectal enema (top) or absolutely no preparation (bottom). A Mantel-Haenszel random effects model was used to perform the meta-analysis and odds ratios are quoted including 95% confidence intervals. MBP: Mechanical bowel preparation.

When only randomised controlled trials were examined[40,46,49,51-57,59,65] (Supplementary figure 6A), again no difference was seen by the use of MBP, a single rectal enema or absolutely no preparation. When observational studies were examined[29,68,69,71,72,74,76,77] (Supplementary figure 6B) overall MPB resulted in no significant reduction in the reoperation rate vs those who did not have bowel preparation but may have had a rectal enema (OR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.64 to 1.15, P = 0.30), as well as when those who has a single rectal enema (OR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.44 to 1.52, P = 0.52), however a significant difference was seen when MBP was compared with patients who received absolutely no preparation (OR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.63 to 0.97, P = 0.02).

Rectal surgery

A total of 11 studies[39,45,46,50,56,57,59,71,75-77] included either only patients who were undergoing rectal or surgery, or outcome measures for the subgroup of patients who had undergone rectal surgery. Ten studies compared MBP with no MBP, with just one study comparing MBP with a single rectal enema[45]. All studies except one[77] included data on anastomotic leak rates, finding MBP not to be associated with any difference in incidence (OR = 0.86, 95%CI: 0.64 to 1.15, P = 0.30). Only seven studies[39,45,46,50,71,75,77] included data on SSI, which also demonstrated no significant difference (OR = 1.22, 95%CI: 0.82 to 1.81, P = 0.33). Intra-abdominal collection and mortality data were similarly only available for five[39,45,46,71,77] and four studies[39,45,46,71] respectively, neither of which were associated with the use of MBP (OR = 0.54, 95%CI: 0.21 to 1.38, P = 0.20; and OR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.29 to 1.82, P = 0.50, respectively). The results in patients undergoing rectal surgery are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effect of bowel preparation on outcome in patients undergoing rectal surgery

| Number of participants (MBP vs No MBP) | Odds ratio (95%CI), MBP vs No MBP | P value | |

| Anastomotic leak | 2351 (1042 vs 1309) | 0.86 (0.64 to 1.15) | 0.30 |

| Surgical site infection | 965 (513 vs 452) | 1.22 (0.82 to 1.81) | 0.33 |

| Intra-abdominal collection | 921 (486 vs 435) | 0.54 (0.21 to 1.38) | 0.20 |

| Mortality | 813 (419 vs 394) | 0.73 (0.29 to 1.82) | 0.50 |

| Re-operation | 1660 (688 vs 392) | 1.57 (1.02 to 2.43) | 0.04 |

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis of 23 randomised controlled trials and 13 observational studies has demonstrated that, overall, the use of MBP vs either absolutely no bowel preparation or a single rectal enema was not associated with a statistically significant difference in the incidence of anastomotic leak, SSI, intra-abdominal collection, mortality, reoperation or total hospital length of stay. When just randomised controlled trial evidence was analysed, there was, again, no significant difference by preparation method in any clinical outcome measure. Finally, when observational studies were analysed, the use of full preparation was associated overall with a reduced incidence of anastomotic leak, SSI, intra-abdominal collection and mortality rates, with these results mirrored in patients receiving MBP vs absolutely no preparation, but no significant differences in those receiving MBP vs a single rectal enema. When a separate subgroup of just rectal surgery was considered, MBP was not associated with a statistically significant difference in anastomotic leak rates, SSI, intra-abdominal collection or mortality, irrespective of whether patients not receiving MBP were given a single rectal enema.

Strengths of study

This study represents the most comprehensive examination of the role of MBP prior to elective colorectal surgery to date. As part of the study plan, the decision was made to include observational studies as well as randomised controlled trials. However, in order to ensure that inclusion of studies of less rigorous methodology did not exert an undue bias, a predetermined analysis of studies of both methodologies was conducted. This revealed that the overall results and those from analysing just evidence from randomised controlled trials were much the same. However, when analysing evidence from observational studies, this resulted in a significant reduction in anastomotic leak, SSI, intra-abdominal collection and mortality rates. The reasons for this difference in results is not clear from this study, but it is possible that selection bias may exert a confounding effect upon the results, and as such the use of MBP in selected patients as determined by the physician in charge may be appropriate.

With the exception of hospital length of stay (I2 = 85%), overall study heterogeneity was low to moderate (0%-34%) for all clinical outcome measures, suggesting the studies to be relatively homogeneous. The risk of bias for the randomised controlled trials included in the meta-analysis (Table 1) was relatively low.

Limitations of study

As the raw mean and standard deviation data were not available on the hospital LOS for all studies, despite several attempts at obtaining this directly from the authors, it was necessary to infer this from what was available (either median and range or interquartile range) using statistical techniques previously described[42]. This is a valid technique which has been well described previously, but this may exert some degree of bias upon the results of the meta-analysis.

There was poor documentation within the studies included regarding the side effects of MBP including the incidence of electrolyte disturbance, fluid depletion and requirement of resuscitation, and renal disturbance or failure, hence this was not included as an outcome within the meta-analysis.

Emerging evidence, much of which has been derived from the studies based upon NSQIP datasets have focused upon the combination between intraluminal antibiotics and MBP and have demonstrated a reduction in SSI rates. However, the data contained within the studies included within this meta-analysis has been scanty regarding the use of intraluminal antibiotics and as such it has not been possible to include this data within the meta-analysis. This may act as a potential confounder when considering the effect of MBP and clinical outcomes.

The studies contained predominantly mixed populations of colonic and rectal procedures, with inadequate documentation to differentiate results between the two, which may be particularly important in addressing the question regarding the use of a single rectal enema as bowel preparation. In addition, there was poor documentation regarding the nature of the anastomoses within the studies included, with a mixture of ileocolic, colon-colon and colorectal. The role of mechanical bowel preparation in various anastomosis types has not been well established. The majority of studies included a predominance of colonic procedures, with some focusing entirely on colonic rather than rectal surgery. Only a small subgroup analysis was available to analyse the impact of MBP in rectal surgery, from which it is very difficult to draw strong conclusions. Further studies are required to discern the importance of a pre-operative enema in this setting. Similarly, the level of documentation in studies regarding laparoscopic vs open surgery was not sufficient in terms of correlation with clinical outcome measures to be able to discern the importance of MBP in this setting. Only one recent observational study has focused entirely on laparoscopic procedures[74] which demonstrated no significant difference in the rates of intra-abdominal septic complications by the use of MBP, and prior to this evidence was purely based on several small studies[38,78].

The nature of the MBP used was inconsistent between studies, and this may introduce a further bias[79]. There was also poor documentation regarding antibiotic usage, particularly in the early studies. Much of the recent literature regarding preparation of the bowel has focused upon the use of oral luminal antibiotics in combination with MBP, with these studies suggesting a potential role for this therapy[26,27]. A recent meta-analysis on this topic has demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of SSI in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery given oral systemic antibiotics with MBP vs systemic antibiotics and MBP[80], thus representing a further weakness in the studies included in this meta-analysis.

Comparison with other studies

A recently published meta-analysis[8] of 18 randomised controlled trials, 7 non-randomised comparative studies, and 6 single-group cohorts compared the use of oral MBP with or without an enema vs no oral MBP with or without an enema. This study found that MBP vs no MBP was associated with no difference in the rates of all-cause mortality (OR = 1.17, 95%CI: 0.67 to 2.67), anastomotic leakage (OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 0.79 to 1.63), SSI (OR = 1.19, 95%CI: 0.56 to 2.63) as well as wound infections, peritonitis or intra-abdominal abscess or reoperation. This study however found considerable variance in the estimation of treatment effects, possibly due to the large range of study methodology included, which may mask a treatment effect seen.

This topic has been reviewed by the Cochrane Collaboration[81-83], with the most recent review conducted in 2011[10]. This included a total of 18 randomised controlled trials in elective colorectal surgery (5805 patients), and demonstrated no statistically significant evidence to support the use of MBP in either low anterior resection, rectal or colonic surgery in terms of anastomotic leakage or wound infection.

A previous meta-analysis has examined the role of MBP prior to proctectomy[12] from eleven publications (1258 patients), although extractable data were only available in a limited number of studies for outcome measures other than anastomotic leakage rates. This study[12] found no beneficial effect from MBP prior to proctectomy with regards to anastomotic leakage (OR = 1.144, 95%CI: 0.767 to 1.708, P = 0.509), SSI (OR = 0.946, 95%CI: 0.597 to 1.498, P = 0.812), intra-abdominal collection (OR = 1.720, 95%CI: 0.527 to 5.615, P = 0.369) or postoperative mortality.

Health policy implications

Worldwide, elective colorectal surgery is performed frequently. Current opinion regarding the use of MBP prior to this surgery is inconsistent[17,18], despite several previous meta-analyses which have suggested this is not useful in reducing postoperative complications[9,10]. The use of MBP is not without cost implications, including the preparation itself and in elderly and frail patients, MBP may also necessitate an additional stay in hospital prior to surgery due to the risk of dehydration and electrolyte disturbance which is associated with considerable additional healthcare costs. This meta-analysis further reinforces that MBP is not associated with any difference in postoperative complication rates, mortality of hospital length of stay, particularly in elective colonic surgery, and as such should not be administered routinely.

In conclusion, this study represents the most comprehensive meta-analysis to date on MBP in elective colorectal surgery. It has demonstrated that MBP vs a single rectal enema or no bowel preparation at all is not associated with a statistically significant difference in any of the clinical outcome measures studied. Given the risks of electrolyte disturbance and patient dissatisfaction, as well as potentially significant levels of dehydration and requirement for pre-admission prior to surgery, MBP should no longer be considered a standard of care prior to elective colorectal surgery.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Mechanical bowel preparation for colorectal surgery has been surgical dogma for decades, despite increasing evidence from the 1990s refuting its benefits. The rationale behind the administration of mechanical bowel preparation is that it reduces fecal bulk and, therefore, bacterial colonisation, thereby reducing the risk of postoperative complications such as anastomotic leakage and wound infection, as well as facilitate dissection and allow endoscopic evaluation. Opponents argue that in the 21st century, with rational use of oral and intravenous prophylactic antibiotics there is no longer a place for mechanical bowel preparation, that it may cause marked fluid and electrolyte imbalance in the preoperative period. As a result of this inconclusive evidence, practice varies between countries and even surgeons in the same institution. We conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis encompassing both randomised controlled trials and observational studies. We sought to address deficiencies in previous studies by including all levels of evidence, separating those in which patients received a single rectal enema vs full or no preparation.

Research motivation

The main topics focused on by this meta-analysis are the role of mechanical bowel preparation vs no preparation or rectal enema alone on postoperative infective complications in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery, as well as in patients undergoing purely rectal resection. This meta-analysis also sought to examine evidence from both randomized controlled trials and observational studies and compare the results of meta-analyses conducted from these evidence sources.

Research objectives

The aims for this meta-analysis were to analyse the effect of mechanical bowel preparation vs no preparation or rectal enema alone on postoperative infective complications in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery, to examine the differences in results between evidence obtained from randomised controlled trials and observational studies, and to determine what effect, if any, bowel preparation had on postoperative complications in rectal surgery. These aims were all achieved by this meta-analysis.

Research methods

We performed an electronic search of the PubMed database and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials to identify studies comparing outcomes in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery treated with mechanical bowel preparation vs either no preparation or a single rectal enema. We performed this meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement. We reviewed full text articles for suitability after excluding studies on the basis of title and abstract. Our inclusion criteria specified that studies must have a minimum of two comparator groups and were either designed as randomised controlled trials or observational studies. Relevant outcome measures were anastomotic leak, surgical site infection, intra-abdominal abscess, mortality, reoperation and hospital length of stay. The analysis was performed using RevMan 5.3 software. Continuous variables were calculated as a mean difference and 95% confidence interval using an inverse variance random effects model. Dichotomous variables were analysed using the Mantel-Haenszel random effects model to quote the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval. These analyses were used to construct forest plots, with statistical significance taken to be a P value of < 0.05 on two tailed testing. A predetermined subgroup analysis was performed for the impact of MBP in rectal surgery specifically using the same methodology.

Research results

This meta-analysis of 23 randomised controlled trials and 13 observational studies has demonstrated that, overall, the use of MBP vs either absolutely no bowel preparation or a single rectal enema was not associated with a statistically significant difference in the incidence of anastomotic leak, surgical site infection, intra-abdominal collection, mortality, reoperation or total hospital length of stay. When just randomised controlled trial evidence was analysed, there was again no significant difference by preparation method in any clinical outcome measure. Finally, when observational studies were analysed, the use of full preparation was associated overall with a reduced incidence of anastomotic leak, surgical site infection, intra-abdominal collection and mortality rates, with these results mirrored in patients receiving MBP vs absolutely no preparation, but no significant differences in those receiving MBP vs a single rectal enema.

Research conclusions

This study represents the most comprehensive examination of the role of mechanical bowel preparation prior to elective colorectal surgery to date and has demonstrated that, overall, the use of MBP vs either absolutely no bowel preparation or a single rectal enema was not associated with a statistically significant difference in the incidence of anastomotic leak, surgical site infection, intra-abdominal collection, mortality, reoperation or total hospital length of stay. Given the risks of electrolyte disturbance and patient dissatisfaction as well as potentially significant levels of dehydration and requirement for pre-admission prior to surgery, mechanical bowel preparation should no longer be considered a standard of care prior to elective colorectal surgery.

Research perspectives

This study represents the most comprehensive meta-analysis to date on mechanical bowel preparation in elective colorectal surgery. It has demonstrated that mechanical bowel preparation vs a single rectal enema or no bowel preparation at all is associated with no difference in any of the clinical outcome measures studied. Mechanical bowel preparation should no longer be considered a standard of care prior to elective colorectal surgery. Emerging evidence, much of which has been derived from the studies based upon NSQIP datasets, has focused upon the combination between intraluminal antibiotics and mechanical bowel preparation and has demonstrated a reduction in SSI rates. However, the data contained within the studies included within this meta-analysis have been scanty regarding the use of intraluminal antibiotics and as such it has not been possible to include these data within the meta-analysis. Further work on this topic should focus upon the role of intraluminal antibiotics in the setting of elective colorectal surgery.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: None of the authors has a direct conflict of interest to declare (Lobo DN has received unrestricted research funding and speaker’s honoraria from Fresenius Kabi, BBraun and Baxter Healthcare for unrelated work).

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: October 5, 2017

First decision: October 18, 2017

Article in press: November 8, 2017

P- Reviewer: Choi YS, Fujita T, Horesh N, Kopljar M S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Katie E Rollins, Gastrointestinal Surgery, Nottingham Digestive Diseases Centre, National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and University of Nottingham, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2UH, United Kingdom.

Hannah Javanmard-Emamghissi, Gastrointestinal Surgery, Nottingham Digestive Diseases Centre, National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and University of Nottingham, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2UH, United Kingdom.

Dileep N Lobo, Gastrointestinal Surgery, Nottingham Digestive Diseases Centre, National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and University of Nottingham, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2UH, United Kingdom. dileep.lobo@nottingham.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Platell C, Hall J. What is the role of mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing colorectal surgery? Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:875–882; discussion 882-883. doi: 10.1007/BF02235369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos JC Jr, Batista J, Sirimarco MT, Guimarães AS, Levy CE. Prospective randomized trial of mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1673–1676. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800811139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichols RL, Condon RE. Preoperative preparation of the colon. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1971;132:323–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung B, Matthiessen P, Smedh K, Nilsson E, Ransjö U, Påhlman L. Mechanical bowel preparation does not affect the intramucosal bacterial colony count. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:439–442. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahajna A, Krausz M, Rosin D, Shabtai M, Hershko D, Ayalon A, Zmora O. Bowel preparation is associated with spillage of bowel contents in colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1626–1631. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Schwenk W, Demartines N, Roulin D, Francis N, McNaught CE, Macfie J, Liberman AS, Soop M, Hill A, Kennedy RH, Lobo DN, Fearon K, Ljungqvist O; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society, for Perioperative Care; European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN); International Association for Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition (IASMEN) Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(®)) Society recommendations. World J Surg. 2013;37:259–284. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nygren J, Thacker J, Carli F, Fearon KC, Norderval S, Lobo DN, Ljungqvist O, Soop M, Ramirez J; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society, for Perioperative Care; European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN); International Association for Surgical Metabolism and Nutrition (IASMEN) Guidelines for perioperative care in elective rectal/pelvic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(®)) Society recommendations. World J Surg. 2013;37:285–305. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1787-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahabreh IJ, Steele DW, Shah N, Trikalinos TA. Oral Mechanical Bowel Preparation for Colorectal Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:698–707. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao F, Li J, Li F. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:803–810. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1361-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Güenaga KF, Matos D, Wille-Jørgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD001544. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001544.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu QD, Zhang QY, Zeng QQ, Yu ZP, Tao CL, Yang WJ. Efficacy of mechanical bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol in prevention of postoperative complications in elective colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:267–275. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0834-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courtney DE, Kelly ME, Burke JP, Winter DC. Postoperative outcomes following mechanical bowel preparation before proctectomy: a meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:862–869. doi: 10.1111/codi.13026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Xu L, Shi G. Is Mechanical Bowel Preparation Necessary for Gynecologic Surgery? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2015 doi: 10.1159/000431226. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang H, Wang H, He M. Is mechanical bowel preparation still necessary for gynecologic laparoscopic surgery? A meta-analysis. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2015;8:171–179. doi: 10.1111/ases.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng S, Dong Q, Wang J, Zhang P. The role of mechanical bowel preparation before ileal urinary diversion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Int. 2014;92:339–348. doi: 10.1159/000354326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Large MC, Kiriluk KJ, DeCastro GJ, Patel AR, Prasad S, Jayram G, Weber SG, Steinberg GD. The impact of mechanical bowel preparation on postoperative complications for patients undergoing cystectomy and urinary diversion. J Urol. 2012;188:1801–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zmora O, Wexner SD, Hajjar L, Park T, Efron JE, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG. Trends in preparation for colorectal surgery: survey of the members of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Am Surg. 2003;69:150–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drummond RJ, McKenna RM, Wright DM. Current practice in bowel preparation for colorectal surgery: a survey of the members of the Association of Coloproctology of GB & Ireland. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:708–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McSorley ST, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. The impact of the type and severity of postoperative complications on long-term outcomes following surgery for colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;97:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung B, Lannerstad O, Påhlman L, Arodell M, Unosson M, Nilsson E. Preoperative mechanical preparation of the colon: the patient’s experience. BMC Surg. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders G, Mercer SJ, Saeb-Parsey K, Akhavani MA, Hosie KB, Lambert AW. Randomized clinical trial of intravenous fluid replacement during bowel preparation for surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1363–1365. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holte K, Nielsen KG, Madsen JL, Kehlet H. Physiologic effects of bowel preparation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1397–1402. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapira Z, Feldman L, Lavy R, Weissgarten J, Haitov Z, Halevy A. Bowel preparation: comparing metabolic and electrolyte changes when using sodium phosphate/polyethylene glycol. Int J Surg. 2010;8:356–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ezri T, Lerner E, Muggia-Sullam M, Medalion B, Tzivian A, Cherniak A, Szmuk P, Shimonov M. Phosphate salt bowel preparation regimens alter perioperative acid-base and electrolyte balance. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53:153–158. doi: 10.1007/BF03021820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London, UK, 2008. 2008. National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Surgical Site Infection: Prevention and treatment of surgical site infection. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scarborough JE, Mantyh CR, Sun Z, Migaly J. Combined Mechanical and Oral Antibiotic Bowel Preparation Reduces Incisional Surgical Site Infection and Anastomotic Leak Rates After Elective Colorectal Resection: An Analysis of Colectomy-Targeted ACS NSQIP. Ann Surg. 2015;262:331–337. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Hanna MH, Carmichael JC, Mills SD, Pigazzi A, Nguyen NT, Stamos MJ. Nationwide analysis of outcomes of bowel preparation in colon surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris MS, Graham LA, Chu DI, Cannon JA, Hawn MT. Oral Antibiotic Bowel Preparation Significantly Reduces Surgical Site Infection Rates and Readmission Rates in Elective Colorectal Surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;261:1034–1040. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiran RP, Murray AC, Chiuzan C, Estrada D, Forde K. Combined preoperative mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics significantly reduces surgical site infection, anastomotic leak, and ileus after colorectal surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;262:416–425; discussion 423-425. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haskins IN, Fleshman JW, Amdur RL, Agarwal S. The impact of bowel preparation on the severity of anastomotic leak in colon cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:810–813. doi: 10.1002/jso.24426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rencuzogullari A, Benlice C, Valente M, Abbas MA, Remzi FH, Gorgun E. Predictors of Anastomotic Leak in Elderly Patients After Colectomy: Nomogram-Based Assessment From the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Program Procedure-Targeted Cohort. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:527–536. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dolejs SC, Guzman MJ, Fajardo AD, Robb BW, Holcomb BK, Zarzaur BL, Waters JA. Bowel Preparation Is Associated with Reduced Morbidity in Elderly Patients Undergoing Elective Colectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:372–379. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3314-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connolly TM, Foppa C, Kazi E, Denoya PI, Bergamaschi R. Impact of a surgical site infection reduction strategy after colorectal resection. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:910–918. doi: 10.1111/codi.13145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shwaartz C, Fields AC, Sobrero M, Divino CM. Does bowel preparation for inflammatory bowel disease surgery matter? Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:832–839. doi: 10.1111/codi.13693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zmora O, Mahajna A, Bar-Zakai B, Rosin D, Hershko D, Shabtai M, Krausz MM, Ayalon A. Colon and rectal surgery without mechanical bowel preparation: a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2003;237:363–367. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000055222.90581.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zmora O, Mahajna A, Bar-Zakai B, Hershko D, Shabtai M, Krausz MM, Ayalon A. Is mechanical bowel preparation mandatory for left-sided colonic anastomosis? Results of a prospective randomized trial. Tech Coloproctol. 2006;10:131–135. doi: 10.1007/s10151-006-0266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van’t Sant HP, Weidema WF, Hop WC, Oostvogel HJ, Contant CM. The influence of mechanical bowel preparation in elective lower colorectal surgery. Ann Surg. 2010;251:59–63. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c0e75c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Contant CM, Hop WC, van’t Sant HP, Oostvogel HJ, Smeets HJ, Stassen LP, Neijenhuis PA, Idenburg FJ, Dijkhuis CM, Heres P, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370:2112–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61905-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scabini S, Rimini E, Romairone E, Scordamaglia R, Damiani G, Pertile D, Ferrando V. Colon and rectal surgery for cancer without mechanical bowel preparation: one-center randomized prospective trial. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Review Manager (Version 5. 3). Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bertani E, Chiappa A, Biffi R, Bianchi PP, Radice D, Branchi V, Spampatti S, Vetrano I, Andreoni B. Comparison of oral polyethylene glycol plus a large volume glycerine enema with a large volume glycerine enema alone in patients undergoing colorectal surgery for malignancy: a randomized clinical trial. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e327–e334. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bretagnol F, Panis Y, Rullier E, Rouanet P, Berdah S, Dousset B, Portier G, Benoist S, Chipponi J, Vicaut E; French Research Group of Rectal Cancer Surgery (GRECCAR) Rectal cancer surgery with or without bowel preparation: The French GRECCAR III multicenter single-blinded randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2010;252:863–868. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fd8ea9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alcantara Moral M, Serra Aracil X, Bombardó Juncá J, Mora López L, Hernando Tavira R, Ayguavives Garnica I, Aparicio Rodriguez O, Navarro Soto S. [A prospective, randomised, controlled study on the need to mechanically prepare the colon in scheduled colorectal surgery] Cir Esp. 2009;85:20–25. doi: 10.1016/S0009-739X(09)70082-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pena-Soria MJ, Mayol JM, Anula R, Arbeo-Escolar A, Fernandez-Represa JA. Single-blinded randomized trial of mechanical bowel preparation for colon surgery with primary intraperitoneal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:2103–8; discussion 2108-9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0706-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jung B, Påhlman L, Nyström PO, Nilsson E; Mechanical Bowel Preparation Study Group. Multicentre randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation in elective colonic resection. Br J Surg. 2007;94:689–695. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jung B. Mechanical bowel preparation for rectal surgery. Personal communication. 2006. Cited In: Guenaga KF, Matos D, Wille-Jorgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD001544. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001544.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Platell C, Barwood N, Makin G. Randomized clinical trial of bowel preparation with a single phosphate enema or polyethylene glycol before elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;93:427–433. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fa-Si-Oen P, Roumen R, Buitenweg J, van de Velde C, van Geldere D, Putter H, Verwaest C, Verhoef L, de Waard JW, Swank D, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation or not? Outcome of a multicenter, randomized trial in elective open colon surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1509–1516. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0068-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bucher P, Gervaz P, Soravia C, Mermillod B, Erne M, Morel P. Randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation versus no preparation before elective left-sided colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2005;92:409–414. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ram E, Sherman Y, Weil R, Vishne T, Kravarusic D, Dreznik Z. Is mechanical bowel preparation mandatory for elective colon surgery? A prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. 2005;140:285–288. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young Tabusso F, Celis Zapata J, Berrospi Espinoza F, Payet Meza E, Ruiz Figueroa E. [Mechanical preparation in elective colorectal surgery, a usual practice or a necessity?] Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2002;22:152–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miettinen RP, Laitinen ST, Mäkelä JT, Pääkkönen ME. Bowel preparation with oral polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution vs. no preparation in elective open colorectal surgery: prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:669–75; discussion 675-677. doi: 10.1007/BF02235585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burke P, Mealy K, Gillen P, Joyce W, Traynor O, Hyland J. Requirement for bowel preparation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81:907–910. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brownson P, Jenkins SA, Nott D, Ellenborgen S. Mechanical bowel preparation before colorectal surgery: results of a prospective randomised trial. Br J Surg. 1992;79:461–462. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leiro F, Barredo C, Latif J, Martin JR, Covaro J, Brizuela G, Mospane C. Mechanical preparation in elective colorectal surgery (Preparacion mecanica en cirurgia electiva del colon y recto) Revista Argentina de Cirurgia. 2008;95:154–167. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fillmann EE, Fillmann HS, Fillmann LS. Elective colorectal surgery without preparation (Cirurgia colorretal eletiva sem preparo) Revista Brasileira de Coloproctologia. 1995;15:70–71. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sasaki J, Matsumoto S, Kan H, Yamada T, Koizumi M, Mizuguchi Y, Uchida E. Objective assessment of postoperative gastrointestinal motility in elective colonic resection using a radiopaque marker provides an evidence for the abandonment of preoperative mechanical bowel preparation. J Nippon Med Sch. 2012;79:259–266. doi: 10.1272/jnms.79.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tahirkheli MU, Shukr I, Iqbal RA. Anastomotic leak in prepared versus unprepared bowel. Gomal J Med Sci. 2013;11:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ali M. Randomized prospective clinical trial of no preparation versus mechanical bowel preparation before elective colorectal surgery. Med Channel J. 2007;13:32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu YJ, Li K, Li L, Wang XD, Yang J, Feng JH, Zhang W, Liu YW. [Early outcomes of elective surgery for colon cancer with preoperative mechanical bowel preparation: a randomized clinical trial] Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2017;37:13–17. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-4254.2017.01.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhattacharjee PK, Chakraborty S. An Open-Label Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial of Mechanical Bowel Preparation vs Nonmechanical Bowel Preparation in Elective Colorectal Surgery: Personal Experience. Indian J Surg. 2015;77:1233–1236. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1262-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamada T, Kan H, Matsumoto S, Koizumi M, Matsuda A, Shinji S, Sasaki J, Uchida E. Dysmotility by mechanical bowel preparation using polyethylene glycol. J Surg Res. 2014;191:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Otchy DP, Crosby ME, Trickey AW. Colectomy without mechanical bowel preparation in the private practice setting. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s10151-013-0990-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roig JV, García-Fadrique A, Salvador A, Villalba FL, Tormos B, Lorenzo-Liñán MÁ, García-Armengol J. [Selective intestinal preparation in a multimodal rehabilitation program. Influence on preoperative comfort and the results after colorectal surgery] Cir Esp. 2011;89:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pitot D, Bouazza E, Chamlou R, Van de Stadt J. Elective colorectal surgery without bowel preparation: a historical control and case-matched study. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109:52–55. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2009.11680371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miron A, Giulea C, Gologan S, Eclemea I. [Evaluation of efficacy of mechanical bowel preparation in colorectal surgery] Chirurgia (Bucur) 2008;103:651–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bretagnol F, Alves A, Ricci A, Valleur P, Panis Y. Rectal cancer surgery without mechanical bowel preparation. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1266–1271. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Veenhof AA, Sietses C, Giannakopoulos GF, van der Peet DL, Cuesta MA. Preoperative polyethylene glycol versus a single enema in elective bowel surgery. Dig Surg. 2007;24:54–7; discussion 57-8. doi: 10.1159/000100919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Memon MA, Devine J, Freeney J, From SG. Is mechanical bowel preparation really necessary for elective left sided colon and rectal surgery? Int J Colorectal Dis. 1997;12:298–302. doi: 10.1007/s003840050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allaix ME, Arolfo S, Degiuli M, Giraudo G, Volpatto S, Morino M. Laparoscopic colon resection: To prep or not to prep? Analysis of 1535 patients. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2523–2529. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim EK, Sheetz KH, Bonn J, DeRoo S, Lee C, Stein I, Zarinsefat A, Cai S, Campbell DA Jr, Englesbe MJ. A statewide colectomy experience: the role of full bowel preparation in preventing surgical site infection. Ann Surg. 2014;259:310–314. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a62643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ji WB, Hahn KY, Kwak JM, Kang DW, Baek SJ, Kim J, Kim SH. Mechanical Bowel Preparation Does Not Affect Clinical Severity of Anastomotic Leakage in Rectal Cancer Surgery. World J Surg. 2017;41:1366–1374. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chan MY, Foo CC, Poon JT, Law WL. Laparoscopic colorectal resections with and without routine mechanical bowel preparation: A comparative study. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2016;9:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pirró N, Ouaissi M, Sielezneff I, Fakhro A, Pieyre A, Consentino B, Sastre B. [Feasibility of colorectal surgery without colonic preparation. A prospective study] Ann Chir. 2006;131:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.anchir.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tajima Y, Ishida H, Yamamoto A, Chika N, Onozawa H, Matsuzawa T, Kumamoto K, Ishibashi K, Mochiki E. Comparison of the risk of surgical site infection and feasibility of surgery between sennoside versus polyethylene glycol as a mechanical bowel preparation of elective colon cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Today. 2016;46:735–740. doi: 10.1007/s00595-015-1239-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen M, Song X, Chen LZ, Lin ZD, Zhang XL. Comparing Mechanical Bowel Preparation With Both Oral and Systemic Antibiotics Versus Mechanical Bowel Preparation and Systemic Antibiotics Alone for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection After Elective Colorectal Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59:70–78. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Guenaga KK, Matos D, Wille-Jørgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD001544. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001544.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guenaga KF, Matos D, Castro AA, Atallah AN, Wille-Jørgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD001544. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guenaga KF, Matos D, Castro AA, Atallah AN, Wille-Jørgensen P. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD001544. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001544.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]