Abstract

Introduction

The accuracy of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers for detecting Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology has not been fully validated in autopsied nonamnestic dementias.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated CSF amyloid β 1–42, phosphorylated-tau, and amyloid-tau index as predictors of Alzheimer pathology in patients with primary progressive aphasia, frontotemporal dementia, and progressive supranuclear palsy.

Results

Nineteen nonamnestic autopsied cases with relevant CSF values were included. At autopsy, nine had AD and 10 had non-AD pathologies. All six patients whose combined CSF phosphorylated-tau and amyloid β levels were “consistent with AD” had postmortem Alzheimer pathology. The two patients whose biomarker values were “not consistent with AD” had non-AD pathologies. The CSF values of the remaining eight non-AD cases were in conflicting or borderline ranges.

Discussion

CSF biomarkers reliably identified Alzheimer pathology in nonamnestic dementias and may be useful as a screening measure for inclusion of nonamnestic cases into Alzheimer’s trials.

Keywords: Atypical Alzheimer’s disease, Primary progressive aphasia, Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, Progressive supranuclear palsy, Neuropathology

1. Introduction

The field of behavioral neurology is progressing toward an era of personalized medicine with the availability of biomarkers. The resultant in vivo determination of underlying pathology for cognitively impaired patients helps to correctly direct individual patients to the appropriate pharmacologic trials. This is particularly important for atypical presentations of neurodegenerative diseases, as there is no one-to-one concordance between clinical phenotype and neuropathologic entities [1]. For example, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) can present in several nonamnestic forms. These atypical presentations are not widely appreciated and such patients are usually excluded from clinical trials because recruitment and outcome criteria focus on memory ability. Greater reliance on biomarkers could remedy this problem but it is first necessary to validate the usefulness of this approach.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analyses of amyloid β 1–42 (Aβ1–42), phosphorylated-tau (p-tau), and amyloid-tau index (ATI) have high sensitivity and specificity as a biomarker for identifying AD pathology in patients presenting with typical late-onset amnestic dementia [2]. However, the utility of using these CSF values as biomarkers for predicting Alzheimer’s pathology at postmortem in patients with nonamnestic presentations has not been fully established.

Here, we evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of CSF Aβ1–42, p-tau, and ATI biomarkers for predicting underlying AD pathology in patients with the nonamnestic clinical phenotypes of frontotemporal dementia (FTD; apathetic and disinhibited subtypes), primary progressive aphasia (PPA), and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) who came to autopsy.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

We conducted a retrospective study of participant at the Northwestern University Alzheimer’s Disease Center and identified those who had a diagnosis of a nonamnestic dementia, CSF biomarkers, and an autopsy diagnosis. Clinical diagnoses had been made according to the published criteria for PPA [3], FTD [4], and PSP [5]. CSF Aβ1–42, p-tau, and ATI were quantified using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay (Athena diagnostics CSF Analysis and Interpretation, Worcester, MA). All autopsies were conducted at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Department of Neuropathology, through the Neuropathology Core of the Northwestern Alzheimer’s Disease Center. The AD pathologic scores are based on the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) criteria for the diagnosis of AD, and all patients diagnosed with AD on autopsy had scores of A3, B3, and C3 [6].

2.2. Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Data for this study came from a longitudinal research program approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University, which obtained written and informed consent for each participant.

2.3. Analysis

We examined the accuracy of CSF for predicting AD pathology at autopsy in the nonamnestic cases. Participants were characterized into one of four groups: (1) consistent with AD, (2) not consistent with AD, (3) borderline, and (4) conflicting, following recommended clinical guidelines (Athena Diagnostics) from the Aβ1–42, p-tau, and ATI [calculated as (Aβ1–42)/(240 + 1.18 (t-tau))] [7–10].

3. Results

Nineteen of the 161 nonamnestic dementia patients who had come to autopsy had a full panel of CSF biomarkers. Nine carried a clinical diagnosis of PPA, eight FTD, and two PSP. Postmortem diagnosis was AD in nine and non-AD in 10. The demographics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical and pathologic diagnoses of participants

| N | 19 |

| Age at disease onset, median | 63 y |

| Age at LP, median | 68 y |

| Years of symptoms at time of LP, median | 5 y |

| Sex | 14 men (74%) |

| Clinical phenotype | No., (%) |

| PPA | 9 (47%) |

| FTD | 8 (42%) |

| PSP | 2 (11%) |

| Pathologic diagnosis | No., (%) |

| AD | 9 (47%) |

| FTLD-tau | 6 (32%) |

| FTLD-FUS | 1 (5%) |

| LBD | 2 (11%) |

| DLS | 1 (5%) |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; DLS, diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; LBD, Lewy body disease; LP, lumbar puncture; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; FUS, fused in sarcoma.

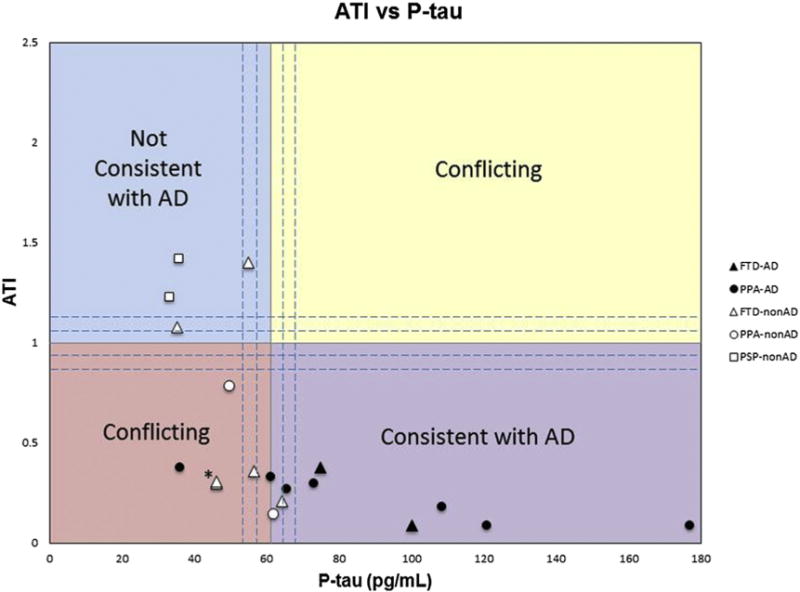

All six patients in the “consistent with AD” quadrant had AD pathology at autopsy; the two patients in the “not consistent with AD” quadrant had non-AD pathology (Fig. 1). Two patients with AD pathology fell within the borderline CSF biomarker range, whereas one patient with AD pathology fell within a “conflicting” quadrant. Eight patients with non-AD pathology remained in the borderline zone or conflicting quadrant.

Fig. 1.

The amyloid-tau index (ATI) versus phosphorylated-tau (p-tau) in picograms per milliliter for all patients with nonamnestic dementia syndromes and autopsy-confirmed pathologies. The upper left quadrant contains values not consistent with AD, whereas the lower right quadrant represents values consistent with AD. The upper right and lower left quadrants represent values with conflicting information. The dashed lines surround the regions considered to lie within a borderline zone and are bound by ATI ranging from 0.8 to 1.2 and p-tau of 54 to 68 pg/mL. Black symbols represent AD pathology and white symbols represent nonAD pathology. Triangles denote FTD as clinical diagnosis, circles denote PPA as the clinical diagnosis, and squares denote PSP as a clinical diagnosis. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy. *Note these are two data points that are very close together, both are white triangles representing FTD-nonAD.

4. Discussion

Few studies have evaluated the utility of CSF Aβ1–42 and p-tau as biomarkers for detecting Alzheimer’s pathology in patients who have atypical, nonamnestic clinical presentations (e.g., PPA and posterior cortical atrophy syndrome [PCA]), and many of these studies have lacked autopsy confirmation [11–13].

Our descriptive results, on a small set of 19 autopsied patients with nonamnestic dementias and postmortem evaluation, show that all patients whose CSF biomarkers fell within the consistent with AD quadrant had confirmed AD at autopsy. Although only two of 10 non-AD cases unambiguously fell in the “not consistent” quadrant, none of the 10 fell in the “consistent” quadrant (Fig. 1). There would therefore be no false positives if CSF biomarkers were used in setting eligibility guidelines for enrollment into AD trials. Furthermore, only a small number (~16%, 3 of 19) of eligible patients would have been excluded from such trials as their biomarker values would place them in the diagnostically borderline zone or conflicting quadrant.

Biomarker development is progressing rapidly. The supplementation of CSF evaluations with amyloid PET, tau PET, and additional markers in blood are likely to improve the in vivo detection of primary pathology in all dementia phenotypes. Judicious use of these biomarkers will increase the accuracy with which patients can be assigned to clinical trials and therapeutic opportunities.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis of amyloid β 1–42, phosphorylated-tau, and amyloid-tau index is a well-established biomarker for amnestic Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, the utility of using these CSF values as biomarkers for identifying Alzheimer’s pathology in patients with nonamnestic dementia is unclear.

Interpretation: Our results suggest that adherence to current AD CSF biomarker guidelines can identify Alzheimer pathology in nonamnestic dementia cases.

Future direction: CSF may be useful as a screening measure for inclusion of nonamnestic cases into clinical trials targeting AD.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Northwestern Clinical Core and its participants.

This study was supported in part by the Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center grant (P30 AG013854) from the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders (grant DC008552), the NIH National Institute on Neurological Disease and Stroke (grant NS075075), and the Florane and Jerome Rosenstone Fellowship.

Footnotes

Author contributions: C.O. contributed toward study concept and design, acquisition and interpretation of data, and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. T.G. and E.R. performed analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. E.V. and E.H. B. contributed toward acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of data. S.W. contributed toward acquisition of data and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. M.-M.M. contributed toward study concept and design, study supervision, and critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content.

References

- 1.Rogalski E, Sridhar J, Rader B, Martersteck A, Chen K, Cobia D, et al. Aphasic variant of Alzheimer disease: clinical, anatomic, and genetic features. Neurology. 2016;87:1337–43. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen N, Minthon L, Davidsson P, Vanmechelen E, Vanderstichele H, Winblad B, et al. Evaluation of CSF-tau and CSF-Abeta42 as diagnostic markers for Alzheimer disease in clinical practice. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:373–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:425–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 9):2456–77. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bensimon G, Ludolph A, Agid Y, Vidailhet M, Payan C, Leigh PN, NNIPPS Study Group Riluzole treatment, survival and diagnostic criteria in Parkinson plus disorders: the NNIPPS study. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 9):156–71. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoonenboom NS, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, et al. Amyloid beta(1-42) and phosphorylated tau in CSF as markers for early-onset Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;62:1580–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000123249.58898.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blennow K, Hampel H. CSF markers for incipient Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:605–13. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blennow K. Cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroRx. 2004;1:213–25. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otto M, Wiltfang J, Cepek L, Neumann M, Mollenhauer B, Steinacker P, et al. Tau protein and 14-3-3 protein in the differential diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 2002;58:192–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tapiola T, Alafuzoff I, Herukka SK, Parkkinen L, Hartikainen P, Soininen H, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid {beta}-amyloid 42 and tau proteins as biomarkers of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes in the brain. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:382–9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toledo JB, Brettschneider J, Grossman M, Arnold SE, Hu WT, Xie SX, et al. CSF biomarkers cutoffs: the importance of coincident neuropathological diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:23–35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0983-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark CM, Xie S, Chittams J, Ewbank D, Peskind E, Galasko D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau and beta-amyloid: how well do these biomarkers reflect autopsy-confirmed dementia diagnoses? Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1696–702. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]